THE DOCUMENTS DIDN’T APPEAR to be in any particular order. I could see at first glance, however, these went well beyond what I had learned from the police records.

Jason Simpson had been a frequent visitor to Cedars-Sinai Hospital and had been treated for some form of psychiatric disorder for which he was being given Depakote, a drug frequently prescribed to prevent seizures, also prescribed for manic episodes in larger doses.

Paging through the documents I counted at least five hospital visits over a three-year period. All five had been to the emergency room. I was no physician, so I couldn’t interpret all I was reading, but it seemed clear to me that at least two of his five visits were the result of suicide attempts.

Jason’s first attempt had been a self-inflicted stab wound to his abdomen on March 17, 1991. This was, I knew, an extremely unusual and painful means of taking one’s life. Jason’s second attempt at suicide was on October 12 of that same year, when he had taken a drug overdose. I could also tell from the documents that after both of these suicide attempts the hospital recommended he undergo psychological testing and evaluation.

I turned the pages eagerly, reading and then rereading passages of Jason’s background. Combined, they formed the tragic picture of a young man crying out for help.

That Jason had been a frequent visitor to Cedars-Sinai Medical Center came as no surprise. I just didn’t know his visits had begun as early as 1984.

Fourteen-year-old Jason had been admitted to the hospital with an injury to his right hip. I could only presume, based on the few scant pages documenting this visit, that he had sustained the injury playing football. I couldn’t be sure, since no history of the patient had been recorded and medical treatment apparently consisted of painkillers and a recommendation that he stay off his feet until he felt better. His father had checked him into the hospital, and his father’s insurance through the Screen Actors Guild had covered the bill, which was paid in full.

Though the visit was nothing out of the ordinary—given Jason’s early promise as an athlete—I did think it was interesting to note that reports of later visits to the hospital revealed that his hip injury had continued to cause him pain and that two years later, while a student at the Army and Navy Academy in Carlsbad, he would undergo surgery at a different hospital. This, presumably, could have been one of the reasons Jason ultimately gave up football for good. I also knew from the profile that Herman King and Chris Stewart had helped put together, Jason hadn’t wanted to play football anyway but desired to go into an entirely different field. He wanted to become a chef. According to the Los Angeles limo driver I had spoken to, Jason had talked about opening his own restaurant as early as high school. But, instead of pursuing his dream, he had gone on to play football at USC, following in his father’s footsteps.

Jason had, of course, eventually secured a job in a restaurant. That we already knew, and it was further verified by his next two visits to Cedars-Sinai, in December and January of 1989 and 1990. Twenty-year-old Jason, then working as a prep chef at the Bravo Cucina Restaurant, at 1319 3rd Street in Santa Monica, cut his right thumb on a meat slicer and had to be taken to the emergency room. The wound wasn’t deep and required no stitches. A follow-up visit consisted of a checkup to see that the wound had healed properly, which it had. These visits were paid for by the Bravo Cucina’s workers’ compensation policy.

Jason was back in the hospital on March 18, 1991, for a far more serious injury, this time a suicide attempt. Now age twenty, Jason had walked into the emergency room assisted by his girlfriend, DeeDee, after having twice stabbed himself in the abdomen with a pair of scissors. He was treated by physicians, given a battery of physical tests, and kept overnight for observation.

According to the report of the psychiatrist who interviewed him on the night of his arrival, Jason had had an argument with his live-in girlfriend, DeeDee, whom he had been dating for approximately eight months. All Jason would initially say about the argument was that it was about “truth.” Exactly what this meant was not clear, but the logical assumption, based on later statements he made to other Cedars-Sinai psychiatrists, was that one or both of them had accused the other of lying or having been deceitful. Jason apparently refused to give any more specific information, only that he and DeeDee had been drinking tequila that night, and that he “felt frustrated that she would not pay attention [to his concerns].” At this time Jason denied having any history of emotional illness or previous suicide attempts.

The attempt had actually occurred the night before, around midnight, after they had given up arguing and had gone to bed. Jason, if he slept at all, slept not more than a few minutes. When he got up out of bed, he and DeeDee began to argue again, at which point Jason impulsively grabbed a pair of scissors and stabbed himself twice in the lower right side of his abdomen. As later examination would reveal, the wounds were not deep and consequently were not considered life-threatening by the two paramedics who were called in to treat him.

It was DeeDee who had called the paramedics and who had pleaded with Jason to go to the hospital. He declined, saying he didn’t want to alarm the neighbors and that he would go by himself to the hospital the next day. According to Jason, he and DeeDee reconciled their differences and went back to bed.

The next morning Jason called his father. Apparently he didn’t tell O.J. what he had done, only that he and DeeDee were not getting along and he wanted to move back into Rockingham. The record did not reveal whether or not he actually did so. It was clear, however, that the wounds in his abdomen had caused him a great deal of pain later the following day, when he and DeeDee had finally gone to the emergency room.

Jason appeared not to be forthcoming about his own medical or psychological history when he was initially interviewed in the emergency room. It was not until the next day, when he was questioned by a psychiatrist and another psychologist and they asked him to voluntarily remain at Cedars-Sinai for further observation, that he admitted to having a history of psychological counseling and treatment.

He admitted that he had been attending therapy sessions once a week for the previous eight months with Dr. Burton Kittay, and that DeeDee had also been seeing Kittay at Jason’s suggestion. The reason Jason gave for these visits was “problems with his relationships with his mother and girlfriend.”

Further, Jason initially denied use of drugs or heavy drinking, but did confess on later questioning that he had used LSD, cocaine, and mushrooms in the past and that he sometimes had “audio hallucinations.” In other words, Jason sometimes heard voices.

However, potentially the most significant revelation to my mind, and something that quite possibly had more to do with his suicide attempt than anything else, concerned Jason’s confession to having undergone testing and treatment at the UCLA Neuro-Psychiatric Institute. According to Jason, he had last visited the Institute three months before. Jason told his attending Cedars-Sinai physicians that he had been diagnosed at UCLA as having juvenile mycological epilepsy, a condition for which he was being treated with Depakote, an anti-seizure medication. He was to take Depakote three times each day.

Not being a psychologist myself, I didn’t know exactly what juvenile mycological epilepsy was, but after speaking to contacts I had back in Dallas, I learned it meant that Jason suffered from an occasional malfunctioning of the neurotransmitters in his brain, which could cause various degrees of impairment, anything from a brief loss of consciousness to an inability to control coordination of his arms and legs—what psychologists called “overactive psychomotor activity.”

Jason had allegedly suffered from this neurological condition since childhood, though it had only been later in life that his illness had been diagnosed and treated. Unfortunately, no other information about Jason’s “epileptic” condition was provided, nor was there a description of how such a “seizure” affected him.

These documents did, however, make one extremely interesting and potentially significant note in the record. They diagnosed Jason as suffering from what they described as an “unknown psychiatric illness,” which manifested itself as “impulsive behavior.” According to the psychiatrist who interviewed Jason, it was stated: “In the past the patient has been impulsive when he was drinking. He would punch the wall, break a glass . . .” This suggested to me that perhaps the “seizures” for which Jason was being given Depakote could be triggered by alcohol or drug use, and were not necessarily those of someone who blacked out or suffered uncontrollable spasms, as those with epilepsy are known to do. It resulted in impulsive or uncontrollable behavior—such as beating a statue of his father with a baseball bat. From what I’ve been able to learn, this type of rage behavior is typical of only a very small fraction of those who have epilepsy and is not at all common among the vast majority of people who have epilepsy.

Jason was strongly urged to remain at the hospital and also to attend therapy sessions at the Cedars-Sinai drug and alcohol abuse center. However, since his stomach wounds were not considered life threatening and there was no proof he would harm himself or others, he could not legally be forced to remain under their care. He asked to leave the hospital and declined to attend their recommended therapy sessions. It is no surprise that he also refused the physician’s recommendation that both his parents and Nicole be notified. He told them he would tell them himself, in his own way.

Interesting to note, Jason was not released from Cedars-Sinai, at least in the formal sense. He simply walked out of the hospital on March 19 at 3 PM, before the nurse had arrived with the instructions on how to care for his wounds and a physician’s formal written recommendation that he undergo psychological testing and therapy.

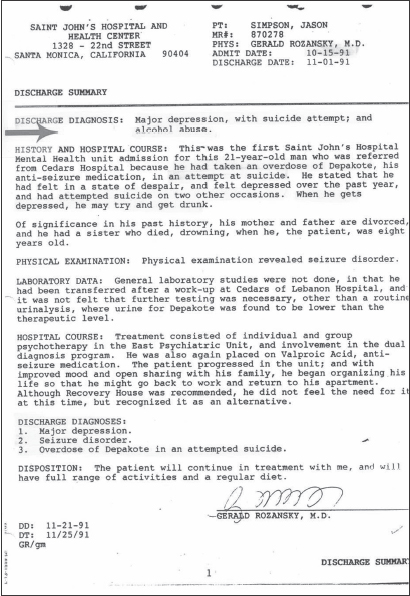

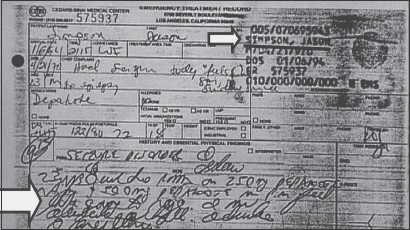

There was no evidence in follow-up reports that Jason had undergone any additional therapy other than his weekly appointments with Dr. Kittay. Jason’s next visit to the emergency room was on October 12, 1991, seven months later, following a second suicide attempt. This time, twenty-one-year-old Jason Simpson, now unemployed and suffering from depression, had taken an overdose of Depakote.

According to the findings, Jason had begun feeling depressed over unspecified “personal problems” relating to his father. At 3 AM on the morning of October 12, after having drunk beer and tequila, he swallowed thirty tablets of Depakote, which amounted to well over ten times the recommended dose. Immediately after taking the drug, Jason had called his mother’s house and left a message on her answering machine. “No matter what,” Jason told her, “I really love you.”

The records further described how Jason’s mother, Marguerite, after hearing the message later that night, went to her son’s apartment. He did not answer the door. Concerned, she had the apartment manager let her into his room, where she found him in a semiconscious state. Paramedics were called and he was taken to the hospital. Emergency room physicians induced vomiting, and he was treated with charcoal to prevent any remaining drugs in his stomach from entering his bloodstream. A few hours later, Jason was conscious, and though feeling sick, was clearly out of danger.

As in his earlier visit to the emergency room, Jason was not immediately forthcoming about the reasons for this suicide attempt. Initially, he also denied ever having attempted suicide before. Physicians either didn’t believe him, or had already looked into his previous records, for this time he was legally forced to remain at the hospital for a precautionary seventy-two-hour hold. During this time, psychiatrists would evaluate his mental condition. His mother, along with his aunt, was present.

Based on Jason’s statements, he had lost his job at the restaurant and was now being supported by his father, who had also given him a car to drive. It was clear that he still suffered from what he called “seizures,” though he now did not specifically identify this disorder as an epileptic condition.

Upon further questioning by hospital psychiatrists and physicians, Jason had finally revealed his previous suicidal tendencies. Only this time he described yet another attempt, the previous June, for which he had been treated in another hospital.

The June suicide attempt, according to Jason, had occurred when he and DeeDee were breaking up and DeeDee was moving to New York. The record was not clear as to exactly what happened; only that he discovered that DeeDee was seeing an old boyfriend. Angry and upset, and presumably high on drugs and alcohol, Jason had punched his fist through the window of the apartment where DeeDee was living. With a shard of broken glass jutting out of the broken window, Jason had slashed his wrist. The only other details Jason gave were that he subsequently received seventeen stitches in his arm.

As he had done earlier, Jason denied having any history of emotional illness, though he was more forthcoming about family problems. He said his entire family was alcohol dependent, and his maternal aunt was a recovering alcoholic. Pressed for more details on his reason for suicide, he said it was an attempt or gesture to call attention to himself because he was unhappy about family matters and about his relationship with his ex-girlfriend. He also said he had serious and unresolved differences with his father, felt distant from him, and blamed him for many of his own problems.

O.J. was contacted by telephone in New York. A transcript of the conversation was not made, but the psychiatrist who made the call reported that O.J. admitted his son had a “chaotic past, involving unstable relationships, alcohol dependence, [and] drug use . . .” He also said that Jason “has been involved in psychotic incidents in the past.”

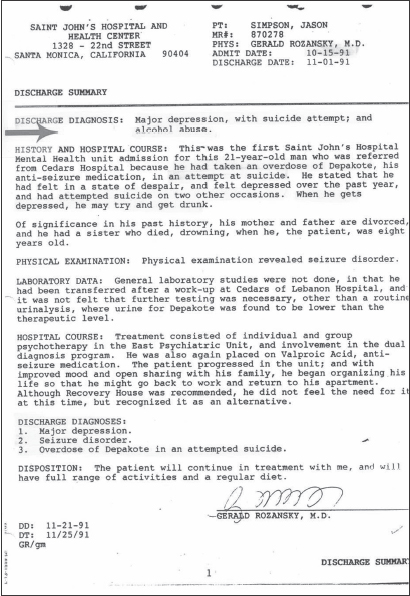

It was noted, however, that upon the request of his parents, three days after being admitted, Jason was transferred by ambulance out of Cedars-Sinai on October 15, 1991, to a mental ward at St. John’s Hospital in Santa Monica.

Jason would make only a few more visits to Cedars-Sinai.

On January 20, 1993, while Jason was awaiting trial for attacking his employer with a kitchen knife, the twenty-two-year-old prep chef would arrive at the emergency room, presumably in a panic, claiming to have run out of his medication, Depakote. His prescription was refilled. As the file revealed, he was now being prescribed a much larger dose of the medication. Almost another year later, on January 6, 1994, just six months prior to the murders, Jason again ran out of his Depakote and went to the emergency room. He needed his Depakote, he told them, because he felt as if he was “going to rage.”