1

THERESIENSTADT

Dusk.

A silken frost settled across the fields beyond the town’s northern ramparts. Here, beneath the volcanic peaks, where grey cones threatened unspeakable violence, a great fortress had risen from the earth, its ravelins, escarpments and redoubts arranged like cascading stars, holding strong against malevolent winds. On top of the third bastion, Jakub R stood gazing out at the Elbe River and, on its furthest shore, the lone spire of Lidomerice’s oldest church.

It was almost a year since he had arrived, since he had trudged through the slush in the streets of Bohušovice, hurrying his mother along on the final leg of their journey to the town once called Terezín. There they waited a week in the sluice yard, lying on straw, filling out forms, eating potatoes, before being shown to their separate barracks. Gusta quickly made a home of it—to her, Theresienstadt was just another exile, no better or worse than the city. With her knitted doilies and pinned pictures, she made her bunk comfortable enough. What little she ate satisfied her meagre appetite. Work in the central laundry was demanding but bearable. And, when the day was done, she had two of her sons, Jakub and Shmuel. She waited for them to come and, at the sound of the curfew siren, as they hurried off back to their barracks, she lay down and closed her eyes.

From the moment he stepped through the camp’s sluice gate, Jakub, however, felt only the chill of confinement. He felt it in his back and in his knees as he crouched down to scrape ice from the pavements. He felt it in his arms and his neck as he hammered wooden boards to the crumbling barriers that separated the inmates from their captors. He felt it as the tepid brown liquid they called ersatz coffee sloshed around in his empty stomach. And he felt it on his cheek as he lay against the frozen straw pillow at night, breathing in the stench of his bunkmates.

Midway through January, Jakub was transferred to the Youth Welfare Department. ‘Formal classes are forbidden,’ said Gonda Redlich, when Jakub reported for duty at the boys’ rooming house on Hauptstrasse. Jakub knew of Redlich from his student days in Prague. A few years his junior, Redlich had been a popular leader in the Zionist youth group movement. His distinct light curls, button nose and thick, round spectacles were instantly recognisable and lent him an unlikely, bookish authority. He had been transported to Theresienstadt early, in 1941, and following a brief tussle with Fredy Hirsch was appointed department head. ‘Teach them songs, play games,’ Redlich continued. ‘And should the lyrics contain some educational elements, or the game include passing through the cities of Palestine, we cannot be blamed for what knowledge the children might absorb.’

Jakub stood before the class that morning and tried to sing but his voice shook and the children laughed. ‘You shouldn’t think about it too much,’ said Redlich. ‘The children get decent food. They have their own barracks with clean sheets and pillows. They do not experience this place like we do. You’ll learn to play and sing and lie. That is your role. And for your efforts you will get extra bread, extra butter, sugar…sometimes even sausage.’ Redlich shook Jakub’s hand. ‘I have put in a request that you be exempted from transport. There’s talk in the Council of Elders of an amnesty, but until then we need to look after our own. Tell your mother you’re safe. All of you.’

The bread was mostly stale, the butter often mouldy or rancid. The sugar was laced with grains of dirt and dead insects. Jakub tasted the sausage only once. It made him double over with cramps as he waited for the latrine. Still, he thanked Gonda Redlich and took his allotted rations so that he could provide for his family. Gusta made of them what she could, glad not to stand in line for the thin broth ladled out in the ground floor dining hall. She made stews and cakes in the warm-up kitchen and brought them back to her room. She divided them into portions, always sure to give herself the smallest one, and watched her sons eat—Shmuel quickly, ravenous from a day in the labour detail, and Jakub slowly. She could not see that he struggled to swallow, his throat clenched as he counted down to curfew.

Gonda Redlich was right. A transport amnesty was declared, but not before six transports had left the camp, taking more than seven thousand people east to a place called Auschwitz. It was, according to the Council, a labour camp. Jakub could see the change in the streets and in the barracks, but most of all he could see it in the classroom: children disappearing overnight, others turning to him when their parents were taken. Many knew him from their time at the school in Jáchymova Street. He sang them songs plundered from a childhood he had tried to escape. He invented stories, stringing them out until he could see the children smile. When Fredy Hirsch came to take the children for exercises in the yard, Jakub sank to the floor and folded his arms over his head. With eyes closed, he imagined himself under his father’s tallis, and willed more stories, more songs to come back to him.

‘Jakub?’

He righted himself against the wall. Gonda Redlich was standing at the door, bemused. Jakub brushed himself down and nodded for Gonda to come in. ‘Sir?’ It still felt strange to address the younger man like that.

‘I’m glad you haven’t left for the day,’ said Redlich. ‘The classes are going well?’

‘Thank you, yes,’ said Jakub. ‘For the children, at least.’

Redlich fumbled in his pocket and pulled out a folded piece of paper. ‘This came from the Council. Murmelstein asked me to give it to you.’ He handed the paper to Jakub. ‘You are to report outside the post office tomorrow morning. Murmelstein was cagey on the details but I know there’s some new register of scholars. You’ve all been summoned.’ Redlich pulled off his spectacles and rubbed them on his shirt. ‘There’s more to you than we knew.’

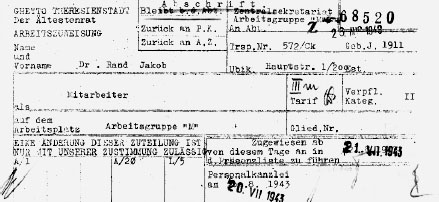

‘Next. Yes, this way…Number?’

‘CK-572.’

‘Name?’

‘R, Jakub.’

‘Jakub Israel R?’

‘Doctor Jakub Israel R.’

‘Yes, yes. Here you are. Your qualification?’

‘Law. Charles University.’

‘I see. And you are working in—’

‘Jugendfürsorge, sir.’

‘Teaching the children?’

‘It is not permitted. Mostly we play, sing, the like.’

‘You take us for fools, Doctor Israel. Thankfully that is not my concern. Family?’

‘My mother and brother. He has stayed on in the mobile labour detail. She was assigned to the laundry.’

‘And your position affords them some…some privilege?’

‘For now they are exempted from transport, yes.’

‘But still you are here.’

‘On Murmelstein’s instruction. I am told this is important.’

‘And with importance comes greater privilege.’

‘I suppose it does.’

‘What is it your sage says? The son must sustain his father and mother according to his capacity.’

‘Maimonides, yes. Almost ten years my father has been in his grave. I am the eldest son.’

‘And so here?’

‘Here the currency is bread. Extra rations, exemptions—’

‘Bread, yes. But also…how do you people call it? Vitamins C and P. Connection and pull. Essential for long-term health. I might add another vitamin: L, luck. That we seem to have in common.’

‘Luck?’

‘Your people have always fascinated me, Doctor Israel. My colleagues jeered when I set about studying you. Still, a passion is a passion. There is no escaping it. Five years ago I was in a small office surrounded by your books, praying for tenure, waiting on the next dinner invitation to remind me I was still alive. Then this…this all began. Those who had mocked me found themselves at the front lines while I am here, where my learning is valued. Such was the tide of history. Luck. Do you believe in the soothsayers, Herr Doctor?’

‘Our sages warn against it. Superstitions can harm only those who heed them.’

‘The Book of the Pious. Indeed. Still, they intrigue me. Those you credit as sages, those you fail to recognise. Take Maimonides, for example. Behind the misplaced devotion, he saw it exactly as it has come to be.’

‘This? Here? With all respect—’

‘But the meaning is undeniable. This war of Gog and Magog. You have already lost. God has moved on, chosen someone else. We of the Aryan bloodline have our Messiah, one who rules from Berlin. Yet here, in this town, in all the lands we control, your people continue to pray for miracles. You cling to folktales, blasphemies. I don’t know what you expect. Soon the war will be over, just as Maimonides said, and when it is, the prophecy will have been fulfilled. The Book of Judges, chapter twelve. You are familiar with the first verse, Doctor Israel?’

‘Not as you interpret it, but yes.’

‘Very good. Then let us begin…’

For weeks after the strange interview Jakub waited but there was no news. He watched the children draw, helped prepare issues of the student paper, Vedem. He tried to speak with Gonda Redlich but he was always busy.

Georg arrived at the start of July. Somehow word reached Jakub the following day; his friend was in the Bodenbach Barracks awaiting registration. Jakub hoped he would be assigned to the Youth Welfare Department. He asked Fredy Hirsch to pass on his request. Back in Prague the children loved him, he said. He shares your views, is passionate about them. He will bring credit to the work. I’d ask myself but…Fredy pulled him aside a while later. No luck. Gonda says he has been promised elsewhere.

Jakub’s disappointment lasted only a few days. One evening, as he trudged back from his mother’s barracks, trailing behind Shmuel, he thought of his friend and how it would feel to have a brother for whom he did not have to care, an equal. He went to the washroom where he splashed his face with water and rinsed his mouth of the foul lentil broth that had crept back up into his throat. Outside, the siren sounded, a call to fitful sleep. The main lights of the barracks flickered then went out, leaving only the dim bulbs that hung from the corridor ceilings. When he reached his bunk, he could see the outline of a man. It had happened before. Lost, confused souls. Souls who had ceased to care. Sometimes a stray from the madhouse in the Kavalier Barracks. The ghetto guard would come soon to collect him. But no, this outline was familiar. The rakish figure. The staccato finger-twitching.

‘Georg?’

‘It is hardly how you described.’

For six months they had merely acknowledged to each other that they were alive: one or two carefully crafted sentences on official card. Jakub had wanted to explain, but this place could not be described. For his part Georg, too, held back. Prague was desolate, every building a reminder of what once had been. He went from his apartment to the museum and back again until the inevitable summons, when he was herded onto a train. Just another transport of Jews.

‘They’ve scattered us around the barracks,’ Georg continued. ‘Father is in Magdeberg, my brothers in Sudeten. Mother is in Dresden, at the other end.’

‘You’ll get used to it. It’s a nightly waltz.’

‘Father will be glad to see you.’

‘He is with the Council of Elders?’

‘Not really, but they keep him close. Light work, tending to the halls mostly.’

‘And you?’

‘Three more weeks in the labour detail then we’ll see what happens.’

‘It says only Arbeitsgruppe M. I’m to be at the gate on Südstrasse by eight.’ Georg turned the narrow slip over as if there might be a clue on the back.

The following night Jakub waited for Georg in their room.

‘Sorry, I was with Father. He sends his best.’

Georg said little about his work, only that it involved books, ones they had not even known existed. Jakub didn’t press the matter. Georg was still adjusting to life in the ghetto.

‘I mentioned you to Otto Muneles,’ Georg said a few days later. ‘Murmelstein has put him in charge of the group.’ Georg sat down on his bunk and began to unbutton his shirt. ‘He is giving a lecture tomorrow. Go and speak with him.’

Otto Muneles had lost little of his gruffness in the months since Jakub last saw him. He was stooped, as if still tending to the dead. He did not move while he spoke, his arms thrust downwards, his hands balled into fists. His voice was a whisper, a seesaw of pitch and punctuation. Jakub found it unsettling that Muneles spoke in public at all, even in the dusky greyness of a barrack loft; listening to someone who communed with the dead tore away the scab of civility.

A polite smattering of applause and it was over. The small audience dispersed, climbing over beams, ducking, tripping, until they reached the stairs. Jakub made his way into the light.

‘Ah, Jakub! Good. Come closer.’ Muneles leaned over the lectern. ‘This group I have…I have gone over the original lists. Your name jumped out immediately. The officer who interviewed you was impressed. He was not certain you had the discipline required, but was confident you had the knowledge. In the end, he approved. It was the Youth Welfare Department that reclaimed you. Maybe Gonda thought he was doing you a favour. They have a healthy supply of Vitamin P. When it comes to drawing up the transport lists, the Commission immediately removes all their cards from the central registry. You can’t be put on a train.’

Muneles gathered his notes and tucked them under his arm. ‘Go back to your room. I just wanted to say that I’ve put in a request to have you transferred. Eichmann is unhappy with our progress. Like everyone else, we work slowly, make the job last as long as we can, but it is the attrition that troubles him. Murmelstein needs this to curry favour. He has installed me as a buffer, I know. He can’t be seen to fail and will sacrifice me if he must. In return he allows me to speak in his name. Now we wait and see where the real power lies.’

Each night, as those around them drifted off to sleep, Georg spoke of paper wonders, the treasures of a mighty kingdom far from the dirt and noise. He guided Jakub’s dreams to a world balanced on a spire of knowledge. The titles alone drew Jakub forward, called his heart to where the rest of him could not follow. Then, in the late summer, he received a yellow ticket.

He was to report to the gate at Südstrasse the next morning.

The Klärenstalt was a short walk from the gate, back in the direction of Bohušovice, tucked beneath the town’s southern rampart. Three rooms sectioned off from the gardener’s hut in what was once a barn. They gave themselves a name too. Not what was printed on their time sheets. Not Arbeitsgruppe ‘M’ or Bücherfassungsgruppe. No, they called themselves the Talmudkommando. These men, who sat on wooden benches, their knees aching, were the custodians of wisdom, of the divine inspiration that had found its way onto the reconstituted pulp of a felled tree. Together they would compress the knowledge into a catalogue that would itself be a library to be plundered, devoured, rewritten.

Their names had once reverberated through the streets of Josefov. Jakub had sat in lecture halls and felt his soul ascend on a chariot of their words. He had read their commentaries on the sacred texts. Mojžíš Woskin-Nahartabi, Rabbi Šimon Adler, Rabbi František Gottschall, Dr Isaac Leo Seeligmann, Josef Eckstein. Jakub saw in them the wise men of his youth, who had huddled around cluttered tables in the shtibl with his father, and argued with an intellectual ferocity Jakub could not fathom. He longed to tell his mother, to say that the spirit of her beloved sat with him while he worked, and guided her son’s pen. But he would not add to her suffering.

In time, Jakub came to know the books by touch alone: the texture of their jackets on his fingertips, the deckled serrations on his knuckles, the pressure on his wrist as he lifted each one from the pile.

Transports resumed in September.

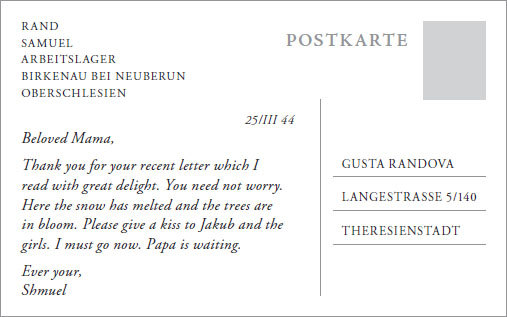

At first it had only been rumour, frantic whispers that cut across New Year’s prayers. Then came the paper slips, left on bunks for the occupants to find at the end of the day. Shmuel was among the first. He ran to Jakub. There must be a mistake. They…they promised. You have the letter. Gusta, too, misunderstood the nature of Jakub’s privilege. ‘Go to the Council,’ she pleaded. ‘We are only three left. It is not right.’ He joined the line of supplicants at the Transport Department, only to be summarily dismissed. ‘This time we have no choice,’ the man said. ‘The Kommandant himself selected the names. Nobody is exempt.’ His mother would not hear it. ‘You should not have left the children,’ she sobbed. ‘With them we were all safe. What good are your books?’ He tried to calm her. ‘Don’t listen to the bonkes. It is just another labour detail. And he will be free of this place.’ He handed her what was left of his rations so she could make Shmuel something for the journey. For three days he made do with ersatz coffee. Six weeks later they received the first postcard. It said only that Shmuel was well and hard at work. Jakub stared at the postmark: Arbeitslager Birkenau bei Neu-Berun.

2

THERESIENSTADT

Gusta rocked the pot over the stove in the warm-up kitchen on the ground floor of the Hamburg Barracks. The aroma was not unpleasant. She knew that most nights they ate better than the others in their room. What was left she would share, a spoonful here, a spoonful there. She had stitched together a family as best she could. Two hours was not enough to be a mother, even before Shmuel was taken. The boys would come straight from work every few days at six and be gone by curfew at eight. Otherwise she was alone. Then the mischlinge arrived: a large transport in early March, dumping an entire community of confused children in their midst. The youngest among them found homes with adoptive mothers but the older ones were forced to fend for themselves.

Two sisters were assigned to the bunks beside her. The older one was surly, protective. She came from Prague. She didn’t need any help, thank you. In a way Gusta found comfort in her brashness; the girl sounded much the same as her own daughter, Růženka, had at that age. The younger sister was different in both looks and manner. She spoke softly, politely, but seemed to feel safe only in her sister’s presence. Gusta tried approaching when the girl was alone, but she shied away and scuttled to her bed, the bathroom or the corridor.

The sisters spoke hurriedly between themselves. Gusta gleaned that their father was also in the camp, a metalworker and roustabout, by the sounds of it. He seemed to arrange to see them but would be late or not show up at all. She heard them lament the nights they had sat on his bunk, picking at the straw, pressing their faces to his dirty sheets, breathing him in, waiting in vain. They spoke of his apologies and his promise of gifts that, they said, never came. They depended instead on their mother. Parcels would arrive regularly, some by the camp postal service, others through less sanctioned means—Gusta heard talk of a gendarme, a Sudeten man who was known to the family. For the first weeks the girls seemed impervious to the resentful stares from those around them. They refused to speak, not even to her. They showed no interest in her sons when they came to visit. And yet, when the lights hissed and went out, they joined in the chorus of sniffs and whimpers. Gusta edged towards them and cooed them to sleep.

Their manner thawed with the summer sun. One evening, when Shmuel arrived, the girls stopped talking and turned to watch. The young man handed Gusta a shirt and a button. Soon Jakub appeared. He hurried across to his mother, kissed her forehead and unloaded food from his jacket pocket—bread, jam, butter, flour, a jar of the acrid Terezín spread made from mustard powder and vinegar. Shmuel rubbed his hands together. ‘Tonight another feast,’ said Gusta. The brothers waited while Gusta rushed off to prepare their meal. When she returned the three of them ate on the bunk as if it were a banquet table.

Before leaving, Jakub and Shmuel kissed their mother, then touched their lips to a grey square of paper nailed to the inside column of her bunk. The next morning the older girl leaned across while Gusta was tucking in her sheet. ‘What is that?’ she asked, pointing to the paper. ‘That is my husband, the father of my children.’ The girl held out a small bonbon. It was all that remained of her most recent package. ‘Please,’ she said. ‘My name is Daša.’

‘And I’m Gusta. Please…call me Auntie.’

‘Your mother…’ Jakub bit the corner of the schnitzel and sucked on the oily crumb. ‘I’ll be at your house every night, I think.’

Daša laughed and cut into her potato. ‘She knows it is my favourite. I’m just worried they’ll spoil.’

‘No. Keep them coming, please.’ Jakub took another bite. He didn’t wait to swallow. ‘We promise they won’t go to waste.’

Gusta put her arm around Irena’s shoulder. ‘It’s good?’ The girl smiled and leaned into her. Gusta held her for a moment, savouring the warmth. Then, to Daša: ‘I’ll come too. If it’s not too much, of course. To think, we’re almost neighbours and we’ve never met.’

‘You don’t leave the house,’ said Jakub.

‘I didn’t know such charming girls existed. I must meet their mother. We have a lot to discuss.’

‘Well,’ Jakub said as he stood up, ‘thank you both. And your mother.’ He leaned over and kissed Gusta on the cheek. She prodded him, nodded towards Daša. ‘Go on,’ she said. Jakub began to crouch but caught himself and smiled awkwardly. ‘Yes,’ he said. ‘Thanks again.’ He knew not to turn around. Gusta would be shaking her head.

December.

Gusta’s room had changed since Jakub’s last visit. A maintenance crew had lopped the top tier from each bunk in the name of beautification. Some of the remaining inmates were packing cases while others bartered with what they would leave behind. Only the mischlinge were sitting casually on their bunks, indifferent to the bustle around them.

‘What’s the news?’ Daša asked Jakub.

‘They’re saying another five thousand people will go. Half on Wednesday then the rest on Sabbath. The lines outside the Magdeberg Barracks stretch past the gate. Those who aren’t seeking rescission are at the Labour Department begging for transfers.’

‘Auntie Gusta is safe?’

‘For now, yes. She longs to be with Shmuel in Birkenau. What do you hear from your father?’

‘Not much. He promises a visit to the new café soon, maybe for Irena’s birthday. His job pays, not enough for an entry ticket, but something. He has found a new circle. They play skat in their barracks after curfew. He’s confident he’ll be here for Irena’s celebration but I don’t hold him to his word. Mama wrote. She is making plans.’

‘And you?’

‘Yes. Me too. One way or another we’ll celebrate.’

The transports left as scheduled. In the streets and the barracks, there was a sense of relief. Of space. Of guilt.

On the morning of Irena’s birthday, Gusta reported sick to the Labour Department. A quick visit to the infirmary confirmed a mild case of Terezínka, the camp illness, diagnosed without examination by a harried nurse. The dormitory was empty by the time she returned but, as promised, each woman had left half a day’s bread ration under her pillow. Jakub, too, had saved his extra rations and Daša had arranged for dried fruit to be brought in from Prague. See you soon, the accompanying note from her mother had said. Gusta crumbled the stale bread into her pot, tipped lukewarm coffee over it and waited for the mixture to thicken. She then stirred in the margarine, jam, sugar, fruit and some extra flour she had traded with a baker for more regular access to the laundry.

They waited until after curfew to celebrate. The women gathered in the centre of the room as Gusta carried in the cake. Together they sang the ‘Terezín March’ while Irena merrily clapped along.

Hey! Tomorrow life starts over,

And with it the time is approaching

When we’ll fold our knapsacks

And return home again.

Where there is a will there is a way,

Let us join hands

And one day on the ruins of the ghetto

We shall laugh.

Irena closed her eyes and blew out an imaginary candle.

3

PRAGUE

At first, the postcards were enough. They came every few weeks, a couple of lines here and there: ‘Just to say we have arrived and all is as it can be. Daddy sends his love too.’ Then: ‘I have found work in the kitchen. Irča and Daddy are also working.’ And: ‘Try as I do to mend them, our socks and underwear are wearing thin.’ Františka Roubíčková sent long letters back, detailed stories of her work in the factory, of their sisters, and of their family in Miličín. But there was no warmth in words alone and, in time, she began to despair. How could she hope to help them when they were so far away? How could she hope to be a mother? That she still had Marcela and Hana was, she knew, only temporary. They, too, would be called for when they reached the requisite age.

She lay awake at night, afraid of what dreams might come. And what of Ludvík? Was there not, in the blood that had brought about their captivity, an obligation to protect, to make good on his sacred oath? She might even find it within herself to forgive if now, when they needed him most, he could finally be a father. As Marcela and Hana slept beside her, Františka buried her face in the pillow, stifling the litany of curses that she spat into the feathers. The hours passed and her rage turned inwards, a caustic mix of exhaustion, fear and loneliness. Most of all, guilt. She was, at last, living well. While most had been sent to munitions factories, she had been conscripted to a small textile firm in Nové Město, sewing garments that would be sent to the Eastern Front. It provided a steady wage, enough to feed three mouths. And that wasn’t even allowing for the visits to Miličín. She had been spending much of her spare time navigating the bureaucracy of obtaining admission stamps for the packages, and the rest stockpiling the twenty kilograms she was permitted to send in each one: boxes with flour, salt, lentils, vegetables, with sweets and dresses. Most of all she sent a mother’s unguarded heart and then waited anxiously for the official postcards of receipt. But that was no longer enough. If she was to hold them again, she would have to go to Theresienstadt.

At dawn she kissed the two sleeping girls and rushed to the factory. She sat at her machine, forcing the material across its dimpled plane. The needle pecked at the seams, snatching them together. When a piece was done, Františka tossed it in the basket at her feet. Before lunch, she rose from her bench and approached the supervisor. ‘I must go for a while.’ The man was not unsympathetic; he had grown fond of Františka. She was skilled, able to patch together a jacket in half the time it took many of the other women. She was also known to slip him the odd cigarette, offer to join him outside for a smoke. He, too, had lost family. His wife’s brother had married a Jewess. For months they tried to obtain an exit visa, bribed everyone they thought might have influence. The supervisor himself had given them money against his better judgment, money that he now wished he had kept. When the borders closed he found himself trapped in a hopeless cycle of charity until the letter came from the Jewish Council summoning the woman and their three children to the fairgrounds. Then he sighed with relief. ‘Certainty, Roubíčková,’ he said. ‘That is what the family needed. Better just to know.’ His wife now spent all her days with the brother, comforting him with lies. She hardly ever came home to see her husband. ‘It has ruined us. But I dare not ask her to choose. Afterwards, we will see.’ He wished Františka luck and sent her on her way.

Františka waited across the road, beneath a canopy of summer blossoms. She lit a cigarette, her third, and studied the uniformed men streaming through the main gate of Peček Palace. The building had grown into its reputation. If she was not mistaken, it had blackened during the occupation. Its very presence was oppressive, this greystone Goliath that stomped on the skulls of her neighbours. Even in the heat of the day, almost all the windows were sealed. Františka puffed one last time on the cigarette then dropped the smoking butt on the ground. She was ready.

‘I wish to see my daughters.’

The man behind the desk had not even looked up when he called her from the queue. She was one of many and had waited for over an hour. Most before her turned around in tears. One man fell to his knees, pleading, crying. His howls echoed through the great hall as he was dragged away. Or perhaps Františka had confused them with the screams from the basement.

‘If they are here, there is reason. Go home and wait. You will be notified soon enough.’

‘No, you misunderstand. They are in Terezín.’

The clerk flinched, lifted his head. ‘They are Communists? Criminals? Jews?’

‘Mischlinge.’ Františka forced the word through clenched teeth.

‘It is not possible.’

‘Everything is possible. I have means—’

‘No favours. It is simply not possible.’ The clerk looked over her shoulder. ‘Next!’

‘I am not leaving. I demand to see my children, to know they don’t suffer.’

‘We all suffer during war, Paní…’

‘Roubíčková. I…sorry…Vrtišová.’

‘Even the Reichsprotektor eats gruel, Paní Vrtišová. Your girls are no worse off than you or I.’

‘I wish to apply for a permit.’

‘I’m afraid such a thing does not exist. The town is closed to visitors.’

‘Four months! Do you hear me? Four months I’ve had to survive on scraps of paper from my girls. Enough.’

The clerk looked nervously towards the approaching guards, shaking his head to ward them away. ‘Paní Vrtišová, I wish I could help. The town is closed. That’s a fact. Then there is the issue of travel within the Protectorate, registration and other such administrative burdens. First you must get…’

‘Give me the papers. I will apply now.’

The clerk flicked through the wad of forms and pulled out two sheets. He slid the glasses from his face, squeezed the bridge of his nose. ‘Do as you wish. What’s a piece of paper if it will calm your nerves? Maintain order. That’s what they tell me. But understand this: nothing will come of it.’

Františka returned every few weeks to renew the application. They all came to know her, this pitiful Aryan woman, her good sense turned septic with Jewish dreams. She took the forms without a word and filled them in at the bench in the corner before defiantly returning to have them stamped and filed.

When the plain enevelope arrived in late November, Františka Roubíčková tore it open and pulled out the paper. It took a moment to sink in: her name, a date, a heavy blue stamp. And beneath it a single word: Bohušovice.

Františka Roubíčková tilted the coat rack against her shoulder and dragged it through the hallway into the lounge. Scarves and coats drooped from its arms, brushing against the doorframe before coming to rest in wilted repose.

This will have to do, she thought as she stepped away from her makeshift tree. It could not stand in the usual corner, to do so would make a mockery of Christmas. Let it remain there awkwardly, in the middle of the room. She grabbed the coats from the rack and threw them against the window bench.

The gurgle of bubbling sour sauce drifted from the kitchen. Františka rushed back to stir the pot. The sauce was thick; specks of flour had congealed into tiny pebbles. In the oven below, orange light glowed over a fat fillet of beef. It was already blue by the time Marcela returned from Miličín, and had the whiff of decay, but Františka salted and scrubbed it before throwing it to the back of her icebox. To have beef at all was a luxury when the ration provided only for the discarded flank of a horse. She lowered the flame and left the sauce to simmer.

Marcela and Hana played in the back courtyard, diving into snowy dunes, squealing with delight. Most of the neighbourhood children had disappeared with their parents and so the building and its surrounds had become their private playground. Each day they invented new games based on the rumours that echoed through the stairwell, games like Razor Blade Man, where they took turns playing Prague’s most feared phantom, hunting each other down with a sharpened twig. Or Gestapo Raid, which was much the same. Františka watched on from the window, proud that she had raised such resilient girls, but more so that Marcela had kept the worst of the occupation from Hana. More than once she had seen the two of them marching together with gusto or singing or sharing parcels of food she had packed for them. She asked them what they were playing, though she knew the answer. It was always the same. ‘Daša and Irča.’

She opened the door and called to them. ‘Come inside and wash. Aunt Emí will be here soon and there is svíčková for lunch. Then a surprise.’ The girls looked up, uncertain. ‘Marcela, watch over the pot while I’m gone.’

Františka headed towards the tram stop in Mladoňovicova Street. As she neared the corner, she glanced at her watch, Ludvík’s watch; she was early. Emílie’s train was not due for a while. A few steps away, the chimes above Žofie Sláviková’s grocery door jingled. Františka ducked inside. Neither woman acknowledged the other. Žofie was eyeing her only other customer with suspicion, notebook in hand, pretending to write orders. Františka stopped to examine each item on the sparsely stocked shelves. She waited for the stranger to leave then picked up a few potatoes and a bushel of sugar before heading to the counter. Žofie Sláviková stamped the cards and handed them to Františka as the chimes went into a jangled frenzy. The two women watched Štěpánka Tičková scurry through the door, muttering to herself, arms wrapped around her hessian satchel.

‘I have it on good authority—’ she spat through cracked lips. It had been like this ever since her co-conspirator Jáchym Nemec was sent to the fortress town: Štěpánka Tičková wandered the streets of Žižkov, searching for a sympathetic ear. Turned away by all, starved of attention, she grew thin and mangy, her voice hoarse.

‘Roubíčková,’ the tattletale snarled.

‘Good afternoon, Štěpánka.’

‘Your daughters—’ Her index finger unfurled with arthritic effort. ‘I have noticed they grow fat.’

Žofie Sláviková slammed her fist on the counter. ‘Štěpánka Tičková! Take what you’ve come for and be quiet about it.’ Františka tucked the paper bag under her arm and rushed out the door to meet her sister.

Emílie sucked the sauce from her bread dumpling before dipping it back in. It was something she’d done since childhood, a habit that had infuriated their mother. ‘So,’ she said as a rising brown tide consumed the spongy dough. ‘What time do you leave?’

‘The train is at eight. I should arrive at Bohušovice around ten. Terezín is not far. And I will return on the last train.’

‘If you don’t mind, I brought gifts.’ Emílie reached into her bag and pulled out a damp cloth sack tied with red ribbon. ‘It’s Christmas cake. Irena’s favourite. For her birthday. Also, these.’ She placed two wooden angels on the table. ‘One for you. One for them. To watch over you all.’

Františka picked up one of the angels and ran her finger along the crest of its wings, up its neck, to the halo. From the lounge she could hear Marcela and Hana searching through Emílie’s case for Christmas presents. ‘Come,’ Františka said.

So this was the surprise, a chance to chase away the storm outside. They plundered the drawers in Františka’s studio and tore at the fabrics they found with scissors, with knives, by hand. They threw the strips in the air and watched them catch on the coat rack’s outstretched arms. In each leaf on their makeshift tree was a forgotten dream, reclaimed and repurposed for merry hearts.

Long after Emílie had nestled into the forgotten recess of Ludvík’s mattress, after Marcela and Hana fell asleep under quilted down, after the angel had been placed on top of the coat rack to bring peace on this refuge of tranquillity and hope, Františka Roubíčková tiptoed over to the dresser and pulled open the bottom drawer. There it was, Daša’s old jewellery box, its hinges broken, the felt worn down to the chipped wood. It was all she could think to grab when Ottla B had tapped frantically at her door that night, almost a lifetime ago, hours after she kissed her eldest daughters goodbye. ‘Please,’ her neighbour had said, dropping a folded piece of paper in Františka’s hand. ‘Take this. For Bohuš.’ Františka was lost for words. In her most desperate hour Ottla had found the courage to run, to escape Žižkov. ‘When this is over, when he comes home, give it to him. Tell him his mother is coming. Promise me you will—’ Ottla’s voice faded on the wind. She looked around, saw two figures turn in from Mladoňovicova. ‘Thank you,’ Ottla said as she ran into the night. It was the last Františka saw of her.

Františka pushed aside the paper, pulled out a small felt pouch and tipped its contents onto the kitchen table. She picked up each ring in turn, testing them on her fingers, under her tongue, beneath the folds of her clothes. Her eyelids grew heavy and she settled on one Ludvík had given her soon after they first made love. A simple gold band. So this was the value of her heart, a currency greater than cigarettes, greater than coffee. Almost weightless, the infinite rounding of life. She pushed it into the moist Christmas cake and waited for dawn.

4

THERESIENSTADT

She danced between the lines in the kingdom of paper. It started with the slightest glimpse, a blonde curl behind a slanting lamed, a flash of skin—perhaps a wrist, a shoulder or even a thigh—through the crook of a beit. By some mistake of gravity he had ascended to the heavens where only gods and angels dwelled. He looked at Georg, at Muneles, at Gottschall, at Seeligmann, but they were lost between pillars of pulp, blinded to this shimmering sprite. She grew more brazen with the days, revealing more of herself on each new page. There was nothing suggestive in her moves, just the sheer delight of freedom. She cared little for his startled gaze. At times she swirled the ink around her in a frantic pirouette until the words blurred like a shroud across her shoulders.

Jakub sat back and wiped his brow. No, it was pointless. It was like leering at a sister, a child. And was he not just seeing her with his mother’s eyes? He knew how Gusta looked on when they talked, imagining what might have been, what still could be. But theirs was nothing more than a convenient alliance: her packages, his privileges, pooled to create a semblance of plenty. Outside the barracks, away from these books, she danced for others. He had seen her in the park on his way back from the bastion, huddled close to a young man under a tree. And what to make of the other times when she would loiter near the gate at day’s end and run the moment she caught sight of Jakub coming up Südstrasse? Jakub was certain he saw the gendarme right himself before hurrying over to unfasten the lock.

Jakub looked at the SS man by the door. He rarely moved, as if asleep. Only once had he stood to attention, when Eichmann himself came to visit, to compliment these shackled scholars, to show that he, too, could speak in their tongue. It is very important work you are doing, gentlemen, Eichmann had said. That was before September, before the Council announced the resumption of transports. Before they took Shmuel away. He should have known. Eichmann’s presence boded ill for them all.

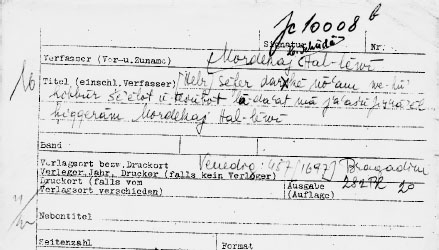

Jakub pressed down on the calfskin jacket of his next book and hoped that when he opened it she would not be there. He read the words: Sefer Darchei No’am, The Ways of the Torah. A book of responsa by Mordechai Halevi, published in 1697. Now item number Jc 10008b. He jotted down the details and a short commentary, first on a blank sheet and then, when he was satisfied with what he wrote, on a standard index card. This time Daša was nowhere to be seen.

5

PRAGUE

II. I. 44

My dearest Emí,

I send you kisses and, of course, Marcela, who I hope remembers to pass on this letter.

Everywhere the winter’s sun plays tricks with the light, making rainbows on the frost, but inside me there is only black. It is two weeks since I saw them, two weeks since I felt the warmth of their fingertips through the wire. Yes, a wire fence. Oh, Emí, forgive me. There was so much I couldn’t tell you when I returned. I was tired but also ashamed, as much for them as for myself. I don’t know what I expected, how I hoped it would be. Perhaps you will understand why I held it inside that night, why the following morning I walked you to the station without a word, why now I must tell you like this.

The train arrived at Bohušovice before eleven. Two men in different uniforms sat on the platform, smoking and playing checkers. One rested a rifle across his lap, the other had a whistle hanging from his neck. When I asked them for directions their faces darkened. The rifleman signalled for the other to deal with me.

The whistle jangled against his buttons as he stood. He looked me over from head to toe before his eyes came to rest on the box under my arm. I pretended not to notice but then the rifleman shook his head and mumbled something. Yes, the other man said. An inspection is in order. Can’t be too cautious. I held open the box and he looked inside. At last he took out the Christmas cake wrapped in its cloth sack. My wife will like this, he said. Anything, I thought. Anything but that. I thrust my hand into the box and—oh God, Emí, I am sorry—I pulled out the carved wooden angel. I held it out to him and for a moment he hesitated. Then the rifleman jumped in. Yes, yes, he said. For my daughter. The other placed the Christmas cake back in the box and escorted me outside.

Bohušovice was a quiet town. The man with the whistle pointed to a road that cut through the centre. Just keep walking, he said. Do not branch off. In the end I would reach the fortress. The people of Bohušovice are no longer accustomed to seeing strangers. I could read it in their puzzled faces. They have closed their minds to what festers beyond. I am told this is the same path they all walked, Ludvík and the girls, but they have since built a railway line so the townsfolk do not feel like accomplices to it all. I walked for half an hour, past the town and through the valley. Emí, it is strange to say but in many ways it reminded me of Sudoměříce. Even in the cold, with snow underfoot, there was a sense of serenity, of beauty. I wondered whether perhaps the girls might feel at home.

Then I saw it. A heavy wire fence with razor wire curled across its top, stretching across the sunken brick walls of an immense fortress. The road led to a gate where a guard stood warming his hands over a fire pit. I greeted him. He responded in Czech; he was a gendarme, not a soldier. We spoke for a while; he seemed uncertain about my presence. One arm rested on his truncheon throughout. I asked him about the daily funeral procession. It would be here soon, he said. Just like Daša told me. I asked if he knew many of the people who lived here and he said he did. I took two cigarettes from my pocket and offered him one. We stood there smoking, taking in the strangeness of our encounter. There was something about him that bothered me. I asked whether he knew my Daša. It was an innocent question, just a way to pass the time, but his face, Emí, his face changed. You know what it’s like to see a pleasant smile contort into a lecherous grin? There was hunger in his eyes. Hunger and knowledge. My chest burned. Yes, he said, letting out a great puff of smoke. She comes here some days during the lunch break. She has been making arrangements for your visit. I am glad to oblige.

I’m sure he would have gone on but we were interrupted by the approaching wail of the funeral procession. The hearse—a horse’s cart wheeled by four men—was heading towards us. In front walked a rabbi with a deep voice, chanting lamentations for those who trailed behind. I saw the awful cargo, a pile of bodies, ten or more, covered only by a sheet that kept lifting with the wind. The gendarme released the latch on the boom gate and allowed the hearse to pass. The rabbi motioned for the bearers to halt and, for a moment, these poor souls rested on the precipice between two worlds. The families set upon the tray, clutching at their loved ones’ arms. They kissed their hands and faces, whispered blessings. Only when the hearse moved on did I see the girls, at the back, among the mourners. They played the part, as if they hadn’t seen their mother waiting there.

The gendarme stood guard while the mourners squeezed against the fence, straining to see the hearse as it rolled off. When at last it was gone, they began the slow march back into the ghetto until only my girls remained. Daša ran over to the gendarme and whispered something in his ear. He shook his head. She whispered something else. Without a word, he took out a cigarette and crossed to a nearby hut, where he sat on the stoop, his face turned away.

How we rushed at each other, Emí. Even through the wire we smothered one another’s faces with kisses, careful not to catch our lips on the freezing metal. It is less than a year but they have grown! Daša is a woman now and Irena no longer looks like a child. Ludvík was unable to come. He is employed in a workshop at the other end of town. I asked if he provides for them. They were reluctant to answer but Daša kissed me again on the cheek and said, as if in jest, He gives what he can. I could not let the atmosphere spoil so I reached into the box and pulled out some socks and other things that I had packed. I threaded them all through the fence, told Irena they were for her birthday but that she should share them with her father and sister. Then we sang together, loudly, joyously, because she was growing up and, no matter what the current situation, it was still Christmas. The gendarme appeared entranced by our ways, as if for a moment he had forgotten himself.

Too soon the lunch break came to an end. Daša said that she was returning to the kitchen and Irena to the sewing workshop. I laid the box at my feet and pulled out the last package. I had wanted Irena to unwrap it but it was too big to pass through the wire, so it was left to me to peel away the cloth. They clapped and cheered when they saw it: the moist Christmas cake. Irena began to laugh. What is it? I asked. What is so funny? Oh, Mama, she said. If only you could have been there to taste my birthday cake. You cannot imagine how we must make do. I passed them both a small handful. Eat carefully, I said. You never know what Saint Nicholas has hidden inside. We are not children, said Daša. Yes, I said, but your teeth can still break.

It was I who got the ring. I felt it the moment the cake hit my tongue. What a fool I must have looked digging into my mouth, catching hold of it while I sucked the dough from its surface! I looked at the gendarme but he was facing the ghetto. I pulled Daša close and dropped the ring into her palm. For Christmas, I said. Use it however you must. I looked again to the gendarme. Remember who you are, I said. Remember what you are. And like that it was over. Daša and Irena gave me one last kiss and ran off back down the road. The gendarme resumed his position by the gate.

Oh, Emí, can you forgive me like I have forgiven Daša? To have kept this secret when my whole life I have told you everything. Why is it that I thought the worst of Daša and that gendarme? Could it simply be that I no longer recognise myself? That my eyes have lost focus? It is true. This situation has dressed us all in fraying rags. Pray that we may stitch them back together.

Always your loving sister,

Františka

6

THERESIENSTADT

Draymen in ragged trousers, their chests bare in the morning light, hauled wooden hearses towards the delousing station. Gaunt faces stared up—elderly and infirm—wincing with discomfort, grey hair tumbling in matted clumps around protruding cheekbones. Soon they would be back, standing outside the kitchens, begging for scraps, but for now the promise of chemical clouds, relief. Jakub and Georg kept their distance; rather be late than infested. At the nearest crossroad they branched off onto Südstrasse. The gendarme tipped his hat, greeted them by name and unlocked the gate. They passed through and headed towards the Klärenstalt.

Spring had thickened the air inside. It was early, or late. Here there was no time. Weiss, the carpenter, scurried from table to table, picking up books, darting back to place them in the waiting crate. The others hunched over their stations. Jakub reached across and took the next book on the stack. A simple siddur, Jakub thought. A prayer book looted from the genizah of a synagogue that was now ash. Worthless. The leather was dry, worn, rubbed, with splits along the spine and edges. Only the clasp remained intact: a tarnished lion, its claws clutching at a small orb. The blackness hid the intricacy of the metalwork, clogging the grooves that fashioned the beast’s fur.

Jakub eased his nail beneath the lion and gently pulled. The clasp strained before springing open with a muted pop. He slid the strap aside and lifted the cover. The first page was blank, mottled by specks of mould and the smudges of impatient fingers. He flipped the page over, then another and another. All blank. Running his hand along the paper, Jakub could feel the faint relief of letters that might have been. The page was uneven: taut around the edges but slack in the middle. He turned several more pages then stopped. He looked around quickly and leaned over the book, shielding it from view.

The handiwork was crude but effective. Slivers of wood had been pasted around a hollowed compartment. The walls were far enough from the fore edge and top square not to arouse suspicion; to the casual eye it was a siddur like any other. The compartment was packed with a clump of tawny dirt, little more than a handful, but enough to fill the space. Jakub pushed the dirt aside, spilling some onto the surrounding paper. There must be something buried inside, he thought, something to warrant such effort to conceal it, but he could find nothing. He pulled a spoon from the buttonhole in his lapel and began to scoop the dirt into his tin cup, watching it suck at the last droplets of water. Soon the compartment was empty, only a few dark streaks across the pastedown at its base. Jakub blew into the space to clear the remaining dust. The streaks held firm, curled, purposeful. Two letters. Mem. Taf. Together Met. Death. He blew again and they were gone.

‘Pencils down, gentlemen.’ It was Muneles. Jakub grabbed the cup, covered it with his palm and rushed out of the Klärenstalt into the late afternoon sun.

‘A lion, you say?’

Professor Leopold Glanzberg had been transferred to the Ghetto Watch after the August purge of young and, in the Camp Kommandant’s opinion, potentially rebellious men. The new Watch consisted exclusively of men over forty-five, men who could be easily subdued, whose only real authority rested in the esteem with which these elders were held by the other Jews. Professor Glanzberg was little more than a kindly face standing at the gate to greet those who had business in the Magdeberg Barracks.

‘And you are quite certain about the orb?’ The black cap with its thin beige cresting wave and scalloped clover insignia was too small for Glanzberg’s head. When he spoke it shifted around, releasing sprigs of grey brush that disappeared into his unruly beard. It was said his mind had softened but his eyes still burned with the intensity of the learned.

‘Yes, it was grasping at a ball,’ said Jakub. ‘The sun, perhaps?’

‘A grape. Yes, a lion picking a grape from its vine. The symbol of Rabbi Judah Löew, the great Maharal of Prague. He had it etched above his door in Široká Street. Few know of this detail. Most only think of the lion. Still, it’s the empty pages that interest me.’

Jakub followed as Professor Glanzberg set off along the street. The town pulsated with the activity of another day’s end. Shoulders collided, dust kicked at worn heels. Gendarmes manned the corners, tried to direct the flow. Jakub tried to pick Glanzberg’s voice from the crowd.

‘And you still have the book?’

‘It is not permitted,’ Jakub said. ‘Weiss will have taken it. I…just…no.’

Professor Glanzberg broke from the weary stream into a narrow alley between two houses. ‘Here,’ he said and turned another corner to reach a deserted cul-de-sac. ‘Please,’ he said and held out his hand. Jakub passed him the metal cup. Professor Glanzberg peered inside, shook the cup, nodded. For a few moments he stood there, as if unsure of how to start. Then:

(The Story of The Book of Dirt…with interruptions)

‘It sounds preposterous, I know. There was a woman, impossibly old. Mad. We didn’t know her name, hadn’t seen her around the community. She started coming to the museum several months before the occupation. She would visit every few days, more so once the Nazis came. We didn’t charge her admission, there was no point. It was obvious she couldn’t pay. She greeted us all warmly, hung her coat near the entrance. Then she would begin her rounds.

‘I was given the task of following her, working out her game. It was the great advantage of my role; I was invisible, just the man in the background tending to the exhibits. I don’t think it would have mattered to her, though. She was blind to all who passed by. It was always the same route through the display halls; she never missed a single exhibit. She talked to herself as she walked, not the soft mutterings of the old and infirm, but full, animated conversations.

‘It took me a few days but I came to understand that she was giving tours, talking to an audience only she could see. On closer inspection—I dared step as close to her as I am to you, pretending to dust a nearby plinth—I saw that she looked only to the gaps between our displays. Her babble seemed to unscramble as I drew near. When I was right beside her I could understand every word she said. Here was a fragment of stone from the Ten Commandments, there was the knife Abraham had intended to use to sacrifice Isaac. In this cabinet was a dried chunk of flesh from the fish that swallowed Jonah, on that wall a spoke from the chariot Elijah rode to heaven. I reported back to the directors. They decided to leave her be. There was a certain charm in her presence. After all, what harm is there in a woman who sees what isn’t there? It is a quality we might all do well to develop.’

‘The Kavalier Barracks are filled with such people.’

‘Pshah…Listen. There was one exhibit towards the end of her tour…something clearly tacked on to appease her imaginary audience. Like all our visitors they hungered for local fare. So she told them of a book, an ordinary siddur, with no identifying marks other than a clasp made of silver, a lion facing the rising sun, its claws stretching outwards, holding a grape. The Maharal’s own prayer book. Nobody dared open it, she said, so great was the respect for this holy man. Just as well. They would have been horrified. Its pages were rubbed clean. Before he died, she said, he gathered the words so that he could take them with him to heaven. But there was another more pious reason for the harvest: he didn’t want to desecrate a holy book. You see, she said, he had one final task before he could depart this world, something that would ensure he could die in peace, and the siddur was to play an integral part. Using the blade with which he had performed countless circumcisions, he fashioned a storage compartment within its pages. Then, she continued, in the middle of the night, while his students and followers slept, he dragged himself up the stairs into the attic genizah of the Altneu Synagogue where, in the back corner, under the old discarded Torah scrolls and holy books, there lay a splintered pine coffin with the disintegrated remains of his beloved golem. Rabbi Löew shuffled over, reached into the area that would have been the corpse’s chest and, whispering a solemn prayer, pulled out a fistful of dirt.’

‘The clay man’s heart?’

‘Precisely. I could see from the glint in her eye that she knew her audience was, like you, feasting on her every word. She went on: For years the Maharal had ascended his pulpit, confident in the knowledge that the golem was resting peacefully above his head. But one day he noticed that it had become an effort to take those steps. He could no longer address his people in the same strong voice that, for so long, had filled them with awe. He was an old man. Soon God would call on him to return to the kingdom of souls. Naturally, his thoughts turned to his child. What would become of it when he was gone? He’d watched his congregation grow sick, watched saintly men turn devious and conniving. They spoke openly of finding the golem, bringing it back to life. With such a servant they would have no need of faith. He summoned his beloved disciples, Yitzchok ben Shimshon Ha-Cohen and Yaakov ben Chaim Sasson Halevi, to prepare them for what was to come. When I am gone, take the dirt and bury it in the cemetery on the hill, he said. Mix it with the earth so it may rest undisturbed, free from the designs of man.

‘A few days later, on what would soon be his deathbed, she said, he was struck with a sudden bout of remorse. To think his beloved child would return to the earth like any other man, that he would be nothing more than a memory. He simply could not bear it. What father can contemplate the erasure of his child? And so he resolved to use what remained of his strength to save the most vital organ, the clay man’s heart. It would live on forever in the known world, in a simple siddur, hidden within the shelves of the eternal library of life.’

‘And you think this…’ Jakub angled the cup towards the old man.

‘Is dirt. By its very nature it is what you make of it. But now I must go. Come by my kambal tomorrow night. Bring the dirt. There is something else you must know.’

Cold water sputtered from the washroom tap. Hands pushed forward, scrubbing, stippling the trough with the muck of a day’s toil. A steamy haze emanated from the stinking bodies crammed together. Some soaked their shirts, squeezed them out, applied the cool dampness to their skin. Others threw handfuls of water against their chests. Jakub held his spot, watching the earth swallow the murky liquid and congeal into a muddy sludge that would not be washed away.

Alone on his bunk he spooned the mud into his hand and rolled it between his palms. It took form, not quite a ball, more the uneven contours of a child’s fist. He squeezed and waited for a response but none came. The clay was heavy, warm. It left no residue on his skin.

When he woke it was still beside him. Who would steal a lump of clay, anyway? Shoes, cups, spoons, yes. But not this. Not dirt. Jakub reached out, slid his finger along its smooth surface. It was still moist. Across the narrow gap between the bunks, he saw Georg beginning to stir. Soon there would be moans, movement, chaos. Jakub slid the clay under the corner of his straw mattress and hoisted himself from the bunk.

For the first time he made mistakes. The books felt foreign, otherworldly. He had to check each detail, double-check. The words would not come, there was nothing to say. Had he not fled the village and escaped the folktales of his ancestors? Was he not a man of reason? Of enlightenment? Why now, in this ghetto prison, must his mind retreat into fiction?

Jakub rested his pen on the desk and looked around. The work continued as normal. That night he would go to the Magdeberg Barracks and find the Professor’s kambal. Jakub knew little of such places, only that they existed. Neither bunkrooms nor apartments, they were the requisitioned nooks under staircases, behind storage shelves, in disused spaces, closed off and decorated for personal use. It was in these kambals that contraband changed hands, that young lovers met for undisturbed trysts, that false kings held court. But it was also where composers filled pages with clefs and crotchets, artists created life with whatever substances they could find, great minds distilled their thoughts. Professor Glanzberg’s kambal was at the back of the Hall of Souls, the central filing room in which every prisoner’s details were kept in triplicate, one copy for this world, one for the next and one to hang precariously in geheinem Terezín, the purgatory of Theresienstadt.

The halls of Magdeberg’s administrative wing were deserted when he arrived. For once the ghetto was at peace. Jakub made his way past the department offices to the door of the Hall of Souls. He held the cup firmly to his shirt. The ball of clay had dried during the day and crumbled. By the time he returned to his bunk it was as he had first found it, an unremarkable mound. Jakub was careful to scoop what he could back into the cup.

The door opened to a narrow staircase lit only by a dull glow from the corridor. Scraggy grey carpet lined the stairs, crushed by the recent passage of ten thousand feet. He removed his shoes and socks and stepped down into the dim passage. The door whined shut behind him, drawn back by a rusted spring. Blackness. Jakub steadied himself against the wall, picking up speed on the stairs as plaster turned to stone against his hand. He knew he had reached the subterranean maze, an arterial system of tunnels that ran beneath the fortress town, where soldiers once scrambled to defend their empress’s name against invading hordes that never arrived and partisans now ferried whatever necessities they could carry on their crooked backs. The hollowed earth held the chill of winters past.

A sliver of light across the ground signalled a door. He searched for a handle but felt only wood and cold metal straps. The light caressed his toes, and with it a warm breeze that carried the drone of a chant. He pressed his shoulder to the door and nudged it open. It was exactly as the bonkes had it: a vast corridor of filing cabinets reaching to the ceiling, lit by bulbs, stretching into the distance. At the far end, Jakub could make out a curtain, behind which were the shadows of two figures sitting in stillness over a raised ledge. The drone grew louder, swirling from all around in the dead air—AH,  H, AH, AV,

H, AH, AV,  V, AV—a diminuendo of sighs.

V, AV—a diminuendo of sighs.

As he approached the curtain, Jakub saw the shadow figures stir. One slid back and rose, growing to a monstrous height then shrinking as it darkened against the fluttering fabric. The curtain was pulled aside to reveal a squinting face. ‘Jakub!’ It was Professor Glanzberg.

‘Please, please,’ the old man said. ‘You’ll have to excuse the state of the place. With every new trainload the filing room expands and I have to make the necessary adjustments. The clerks fuss over the files. Bureaucrats! The noise is unbearable—paper brushing against paper…I tell you, it toys with one’s sphincter. Then they ship a trainload off and I’m back to where I started.’ Professor Glanzberg held open the curtain to allow Jakub through.

It took a moment for Jakub’s eyes to adjust to the harsh light of an unshaded floor lamp near the hanging divide. The kambal was sparsely appointed: a single mattress wedged into the corner, a plain bookshelf against one wall and a table near the centre with four chairs—short, like those found in a house of mourning—placed around it. The man sitting down did not turn around but Jakub recognised his shape.

‘In Prague we were ten,’ said Otto Muneles without waiting for Jakub to sit. ‘Now we are two. The Council of Formations. Or what’s left of it. For years we gathered in the attic of the Altneu where nobody dared tread, but here…Please, take a seat.’ Jakub lowered himself onto a chair. ‘We weren’t sure that you’d come,’ continued Muneles. ‘You have enough to worry about without this. And old Leopold’s tales…I know how it must sound.’

‘Prague is a city of stories,’ said Glanzberg. ‘Words are in its very mortar. Mostly we dismiss what we hear as legend or gossip. But know this, young Jakub: much of it is true. Take us, for example.’

Muneles shifted in his chair. ‘Five hundred years ago, Rabbi Löew had a private audience with Emperor Rudolf II. To this day what they discussed remains a closely guarded secret.’

‘Rudolf was a kind, tolerant man,’ said Glanzberg. ‘But he was surrounded by advisers who wished only ill for the Jews, and who filled the emperor’s head with false accusations: sorcery, witchcraft, all kinds of treachery. Naturally, he grew fearful of what he had been told, but he trusted the great rabbi. He trusted in his reputation for learning and wisdom and honesty. And so the emperor summoned Rabbi Löew to an apartment in the castle where they could speak in private, and laid out his offer: Rabbi Loew was to investigate the legends and report back to the emperor. Bring them to me, Rudolph said, so that my mind will be at ease. Together we can banish your sheds and mazziks from these lands. In return, the emperor vowed to revoke all expulsion orders that his father had made, and allow the Jews to live freely in his kingdom.

‘Rabbi Löew rushed back and called together nine of his most trusted friends to form the Council of Formations, and appointed as its leader the one who dwelled with the spirits, the head of the Chevra Kadisha. On the first night, they met in the attic of the Altneu. We will do as he asks, Rabbi Löew said. We will make the proper enquiries. Then we will report back that it is all rumour, the superstitions of country folk. Quell his fears, yes, but whatever we find we must save. Beware the king with good intentions.’

‘Since then,’ said Muneles, ‘it has fallen upon those in my position to continue the holy charge. Here we are. Still searching.’

‘There are others,’ said Glanzberg. ‘All working with the burden of their titles. The librarian, the architect, the slaughterer, the keeper of youth. You’d be surprised by the evidence they’ve found. The brick thrown at King Wenceslas—for which, legend has it, the quiet Jew Shime Sheftels paid a martyr’s price—uncovered by my predecessor in 1753. Then, at the turn of the last century, a lump of dripping coal, prised from the hand of a dead woman as her body was being prepared for the grave. It was brought before the Council and tested extensively. Wouldn’t you know, it proved to be just as its finder suspected: a magical artefact from the underwater kingdom, one of the gold coins given by the water sprite of the Vltava River as a dowry for his beloved on condition that her family remain absolutely silent. Legend has it that when the girl’s mother could keep the secret no more, the riches turned to ashen clumps that continued to cry freshwater tears…

‘It is a complex charge,’ continued Glanzberg. ‘These legends have a way of growing into themselves, multiplying. In every one there is the seed of the next. Our job is to examine those seeds, but also to scatter others so that the Jews do not make idols of them.’

‘And so we obfuscate,’ said Muneles. ‘We muddy the waters. In that way we, too, have grown into ourselves, into our names. And we have lost control.’

Professor Glanzberg rocked back and forth in his seat, as if praying. ‘When the stories began to circulate about Rabbi Löew, the Council of Formations did what it could to cultivate them. Let him become a myth, a legend. Then the Germans came.’

‘They came and it all changed,’ said Muneles. ‘We met as the Council of Formations always did, in the attic. Leopold here saw in the occupation a chance to gather whatever artefacts remained and test them for evidence of folk magic. We approached the Department of Rural Affairs to petition the authorities, and ask that everything from around the Protectorate be shipped to Prague.’

‘We also sent out teams in the city,’ said Glanzberg, ‘under the strict watch of a particular Jewish brute, to search every house that had been left empty by deportation. Only the odd piece proved to be of any worth. There were, however, two things…two things that made us reconsider the legend of Rabbi Löew.’

Jakub felt his fingers tighten around the metal cup. He pulled it back along the table, towards him. It seemed somehow heavier, as if the dirt inside had grown dense with Glanzberg’s words.

‘The first,’ said Muneles, ‘was a simple wooden box. On its sides were unsophisticated carvings, symbols that might have been a forgotten language or just mindless doodles. We could find no opening, nothing to indicate its purpose. We’d have tossed it aside had it not started jingling every time our colleague Pavel Pařík picked it up. For two days we watched as it rang out or stayed mute according to his presence. It became something of a game. We would place it wherever we thought he’d be going next. We even joked about giving it as a gift to his wife. Then, on the third day, he didn’t come to the museum. At ten o’clock we received the call. Pavel Pařík was dead. He’d suffered a stroke overnight. It was then that we remembered the story: Rabbi Löew, in an effort to cheat death, once made a box that would chime out whenever the dark angel was approaching. Leopold rushed with the box to the nearby hospital and, just as we feared, the moment he stepped inside, it began to ring out and shake uncontrollably.’

‘The second thing,’ said Glanzberg, ‘was a great deal more confounding. You are no doubt aware that the whole fascination with Rabbi Löew and his man of clay is based mostly on the work of the Polish Rabbi, Yudl Rosenberg, and his book Nifla’ot Maharal. Rosenberg claims to have come across the manuscript about Rabbi Loëw and the golem in the Royal Library at Metz in Northern France. He claims it was written by Rabbi Löew’s own son-in-law.’

‘But neither the library nor the son-in-law ever existed.’

‘In his introduction,’ continued Glanzberg, ‘Rosenberg wrote of a second manuscript, penned by Rabbi Löew himself, that Rosenberg was willing to sell for eight hundred kopeks. An exorbitant amount at the time. He could be certain that nobody would take him up on it.’

‘Except,’ said Muneles, ‘it appears that somebody did. And it was sold on through the years until it fell into the hands of the industrialist Max Landsberger. We found it in his son’s house. Actually, you and Georg found it. You just didn’t know.’

‘We were forced to review our position on Rabbi Löew.’ Professor Glanzberg gestured towards the cup. ‘We had to face the possibility that the tales about him were real, that his golem was real.

‘Prague was all abuzz over the clay man. Books, movies, plays—a steady stream to fill their heads with wonder. We began to hear new stories: the Nazis had tried to burn down the Altneu Synagogue only to be thwarted by the raging golem; a senior Gestapo man was found dead on the stairs leading to the attic, his body battered and broken. The people had found in this golem a saviour more tangible than any messiah. The transports were already in full swing. If only the force of the golem’s fury could be released before the last Jew was taken away. Frightened fathers beseeched the chief rabbi to open the attic, to let the clay man out to save their children. The rabbi came to me one night. What could he do? We both knew there was nothing to be found up there. The genizah had been cleared out years ago and, other than ten wooden benches upon which we would sit to meet, the attic was empty. But what rabbi will take away hope when it is all that is left to his congregants? And who will admit to having broken Rabbi Löew’s prohibition forbidding anyone from ever entering the attic again?’

‘So we did the only thing we could do,’ said Muneles. ‘We returned to the sources, studied every permutation of the legend, scoured the notes of our predecessors, hoping to find sign of the creature. Perhaps they had been too quick to dismiss it.’

‘Picture this if you will: ten of Prague’s greatest minds, crawling along the banks of the Vltava River,’ said Glanzberg, ‘feeling for the spot where the clay had maintained its shape. We searched the cemeteries, dug up the graves where damaged books and Torah scrolls were buried, went to Rabbi Löew’s old house in Široká Street and lifted the floorboards. But we found nothing.’

Jakub peered into the cup. The dirt rested loosely inside, a few clay pebbles on top. He wanted to tell the men about it, about how it had kept its form, how it had stayed moist and firm beside him for one night before drying and crumbling in his hands. But, all of a sudden, he was not so sure. Had that even happened? Could it be that his memory was being shaped by the stories they told, that they were building golems in his mind? He shook the cup and watched the dirt tumble from side to side.

‘It shames me to say,’ continued Glanzberg, ‘that we even tried to create him anew. Only this year, just before Passover, Otto and I went down to the water’s edge and fashioned a figure from the mud. We followed the formula, recited the two hundred and thirty-one gates in the Sefer Yetzirah, just as the great Rabbi Eleazar of Worms instructed. We stayed there until morning, chanting, praying, crying and pleading, dancing in circles until the water lapped at our inanimate lump and called it back to the river. We trudged home but there was no clay man to keep us company.’

‘We had failed,’ said Muneles. ‘And God laughed from on high, thunder rumbling in the distance.’ He rested his hands on the table and lowered his head. Jakub had not seen him so uncertain, so defeated. Then: ‘I returned to the museum and kept an eye out for artefacts until, two months later, I received my summons and was brought here.’

‘The work continues in the city,’ said Glanzberg. ‘We made sure to leave one of our own in charge of the museum.’

‘Old Jakobovits.’

‘Pieces of all kinds come before him and his team examines them, tests those that might be of any significance, squirrels them away in the piles of confiscated goods. Here we only have books. Until now we had found just one item: the list of names read by Rabbi Löew to the Angel of Death at the cemetery gates in defence of his congregation. And now this…’

‘The most unlikely evidence of all.’ Muneles looked at the cup in Jakub’s hand. ‘When Leo came to tell me, I thought the fortress had gone to his head. Nowhere has the story of the hollowed book been written down. Could it be that the mutterings of a senile woman hold the key to the greatest mystery our city has known? The Council had already dismissed it out of hand. Now, in our little Klärenstalt, a siddur matching her very description appears…It is too much.’

‘There is no way to test it here,’ said Glanzberg. ‘And woe to us all if the administration gets hold of it. No, we must get it to the city, to Jakobovits. He must store it with the rest of the artefacts so that it might survive even if we do not. Who knows, when this is all over, perhaps it can be taken to the banks of the river and mixed with the mud so that the creature may rise again and avenge us.’

Otto Muneles pulled a crumpled paper sachet from his pocket and flattened it against the table. Jakub made out the word ‘Sugar’ stamped in faded ink. ‘Put it here,’ said Muneles.

Professor Leopold Glanzberg took the cup from Jakub and tipped the dirt into the bag, clapping his palm against the cup’s base to be sure he’d emptied it all. ‘There are boys,’ said the professor, ‘young men who know their way through the tunnels, who have contacts in the towns outside the fortress gates. I will take it on my daily rounds, see it gets to one I can trust. Dr Jakobovits will have it in days. And Jakub?’ He placed the sachet on the table and took Jakub’s hands between his. ‘Not a word to Georg. In the past I’ve tried, but he does not listen. Now this…I’m afraid he will think—’

Muneles picked up the sachet and rolled the top closed. Holding it in his palms, he tilted back his head and began to chant quietly: ‘A heart with no form, with no chambers, no vessels. A heart that does not beat, that cannot ache, cannot love. A heart that can be scattered to the wind just as easily as moulded with the ground. What good is a heart alone, with no body, no home? It can only stain those around it with blood. AH,  H, AH, AV,

H, AH, AV,  V, AV.’

V, AV.’

Jakub tried to push it from his mind. That night, a heaviness set in his chest, a soft wheeze that whistled when he slept. By morning it had worsened, a burning in his throat. He could not swallow. With the pain came the chance of escape. Jakub put in for a transfer to the hospital barracks, where he was misdiagnosed with the early stages of pneumonia. He coughed and choked his way through four uneasy nights before he was deemed well enough for light work and discharged.

As he made his way back along Neu Gasse towards the Hannover Barracks, Jakub saw Professor Glanzberg scurrying about near the entrance to the girls’ home. Catching sight of him, Glanzberg stood to attention, clicked his heels and ran up the road to greet him. ‘Jakub,’ he said, trying to catch his breath. ‘Have you heard? No? There are rumours. Nothing official yet but…transports. Any day now. And worse. Our boy. The tunnel. He was captured. They’ve taken him to prison in the Small Fortress. And they’re searching the kambals, clearing them out. Here!’ Professor Glanzberg stuffed something into Jakub’s pocket. ‘A sympathetic gendarme from the security detail. Take it. Keep it safe and wait for word from Otto. We will find another way. Now go.’

The Hannover Barracks were deserted. Beds made in haste, rags strewn across the lumpy covers. The distant clamour of a cleaning detail. Jakub opened the battered case at the foot of his bed, fished the paper sachet from his pocket and placed it inside. There were others: salt, flour, lentils. A small reserve of rations, should the need arise. Jakub locked the case and set off to find his mother in the Hamburg Barracks.

7

THERESIENSTADT