Just then, one of the young employees of the company walked in the room and whispered something to Yusuf. Excusing himself, Yusuf quickly followed the worker out of the room.

After he left, Pettis said to Avi, “I’m not sure what Yusuf meant by a heart being at peace. I’d like to hear more about that.”

“Sure,” Avi said. “To begin with, let’s compare Saladin’s recapture of Jerusalem to the earlier capture by the Crusaders.” He looked at Pettis. “Do you notice any differences in the two victories?”

“Certainly,” Pettis responded. “The Crusaders acted like barbarians.”

“And Saladin?”

“He was almost humane. For someone who was attacking, anyway,” he added.

“Say more about what you mean by humane,” Avi invited.

Pettis paused to gather his thoughts. “What I mean,” he finally said, “is that Saladin seems to have had regard for the people he was defeating. Whereas the crusading forces seem—well, they seem to have been barbaric, as I said before. They just massacred all those people as though they didn’t matter at all.”

“Exactly,” Avi agreed. “To the initial crusading forces, the people didn’t matter to them. That is, the Crusaders didn’t really regard them as people so much as objects or chattel to be driven or exterminated at their will and pleasure.

“Saladin, on the other hand,” Avi continued, “saw and honored the humanity of those he conquered. He may have wished they had never come to the borders of his lands, but he recognized these were people he was doing battle with, and that he therefore had to see, treat, and honor them as such.”

“So what does that have to do with us?” Lou asked. “You’re talking about a nine-hundred-year-old story, and a story about war at that. What does it have to do with our kids?” Thinking of what Yusuf had said about his company, he added, “And our employees?”

Avi looked squarely at Lou. “In every moment, we are choosing to be either like Saladin or like the crusading invaders. In the way we regard our children, our spouses, neighbors, colleagues, and strangers, we choose to see others either as people like ourselves or as objects. They either count like we do or they don’t. In the former case, since we regard them as we regard ourselves, we say our hearts are at peace toward them. In the latter case, since we systematically view them as inferior, we say our hearts are at war.”

“You seem to be pretty taken by Muslims’ humanity toward others and others’ inhumanity toward Muslims, Avi,” Lou objected. “I’m afraid that is quite naive.” He thought of what he knew of Avi’s history. “And surprising, coming from one whose own father was killed by the people you are lauding.”

Avi heaved a heavy sigh. “Yusuf and I have been speaking of no one, Lou, but Saladin. There are those who see humanely and those who don’t in every country and faith community. Lumping everyone of a particular race or culture or faith into a single stereotype is a way of failing to see them as people. We are trying, here, to avoid that mistake, and it seems to me that Saladin is a person we could learn from.”

Lou fell silent in the face of this rebuke. He was beginning to feel lonely among the group.

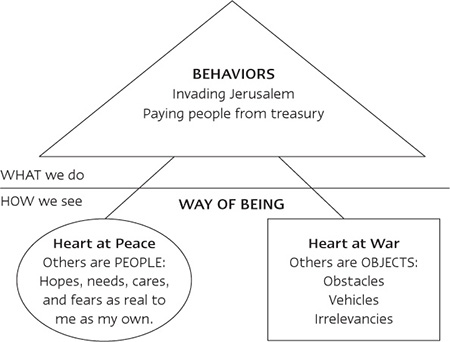

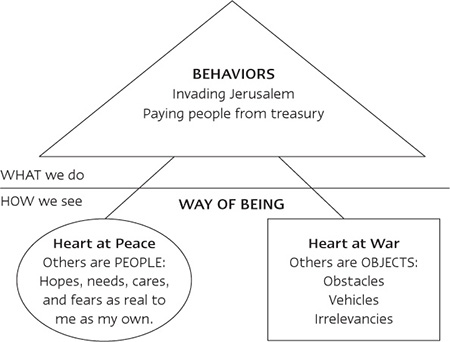

“The contrast between Saladin’s taking of Jerusalem and the Crusaders’ taking of Jerusalem,” Avi continued, “teaches an important lesson: almost any behavior—even behavior as stark as war—can be done in two different ways.” At this, he went to the board and drew the following:

THE WAY-OF-BEING DIAGRAM

“Think about it,” Avi said, turning to face the group. “The Saladin story suggests that there is something deeper than our behavior—something philosophers call our ‘way of being,’ or our regard for others. The philosopher Martin Buber demonstrated that at all times, no matter what we might be doing, we are always in the world in either an ‘I - It’ or ‘I -Thou’ way. In other words, we are always seeing others either as objects—as obstacles, for example, or as vehicles or irrelevancies—or we are seeing them as people. To put it in terms of the Saladin story, there are two ways to take Jerusalem: from people or from objects.”

“Who cares how you take it, then?” Lou blurted, suddenly feeling energized for another round. “If you have to take it, you have to take it. It’s just that simple. A soldier doesn’t have the luxury of worrying about the life of the person who is staring down his lance or barrel. In fact, it would be dangerous to invite him to consider that life. He might hesitate when he needs to fire.”

This comment crystallized a doubt that had been creeping up within Pettis as well. “Yes, Lou, that’s a good point,” he said. “What about that?” he asked Avi. “Lou’s worry about soldiers seeing their enemies as people is legitimate, is it not? I see problems with that as well.”

“It seems like it might be a problem, doesn’t it?” Avi agreed. “But was it a problem for Saladin?”

“Yes, it was,” Lou retorted, emboldened by Pettis’s support. “He was completely taken advantage of by the enemies he let leave with Jerusalem’s riches.”

“Do you suppose seeing others as people means that we have to let them leave with riches? That it means we must let others take advantage of us?” Avi responded.

“Well, it seems like it does, yes,” Lou answered. “At least, that’s what it seems you’ve been implying.”

“No, that’s not his point,” Elizabeth disagreed. “Look at the diagram, Lou. You have the behaviors at the top and the two basic ways of seeing others at the bottom. Avi’s saying that everything he’s written in the behavior area—taking Jerusalem, for example, or paying people from the treasury—can be done in either of those ways of being, with a heart at peace or a heart at war.”

“Well then who cares which way you do it?” Lou repeated. “If you need to take Jerusalem, just take Jerusalem. Who cares which way you do it? Just get on with it!”

Avi looked thoughtfully at Lou. “Cory cares,” he said.

“Huh?”

“Cory cares.”

“He cares about what?”

“He cares whether he’s being seen as a person or an object.”

Lou didn’t say anything.

“Seeing an equal person as an inferior object is an act of violence, Lou. It hurts as much as a punch to the face. In fact, in many ways it hurts more. Bruises heal more quickly than emotional scars do.”

Lou looked as if he were about to respond to this but finally didn’t, slouching back in his chair as he argued with himself about his son.

“The inhabitants of Jerusalem surely cared as well,” Avi continued. “But even more than that, you care, Lou,” he added. “You care whether you are being seen as a person or as an object. In fact, there is little you care more about than this.”

“Then you don’t know anything about me,” Lou retorted, shaking his head in disagreement. “I couldn’t care less what others think about me. Just ask my wife.”

The sad irony of his comment, as autobiographical as it was on this particular day, didn’t penetrate Lou. At his side, Carol blushed slightly, clearly unready for the attention that suddenly came her way.

Avi smiled good-naturedly. “Actually, Lou, I think you do care.”

“Then you think wrong.”

“Maybe,” Avi allowed, nodding. “It wouldn’t be the first time. But here’s something to consider: has it been important to you to get others to agree with you this morning?”

Lou remembered his earlier hope that Elizabeth shared his views and the energy he felt when it appeared that Pettis did.

“If so, you do care,” Avi continued. “But ultimately, you are the only one who will be able to answer that question.”

Lou felt a tingle of pain, the way one does when a foot or limb has been asleep and is just beginning to revive itself.

“This issue of way of being is of great practical importance,” Avi continued. “First of all, think of a difficult business situation—say a complicated negotiation, for example. Who do you think would be more likely to put together a deal in difficult circumstances, a negotiator who sees the others in the negotiation as objects or one who sees them as people?”

This question piqued Lou’s interest, as he was in the middle of a union negotiation that was going nowhere.

“The one who sees others as people,” Pettis responded. “Definitely.”

“Why?” Avi asked.

“Because whether you’re talking about negotiators or anyone else, people don’t like dealing with jerks. They’d just as soon poke jerks in the eye as help them.”

Avi chuckled. “That’s true, isn’t it,” he agreed. “In fact, have you noticed that we sometimes choose to poke another in the eye even when doing so harms our own position?”

This question swept Lou’s thoughts back to an emergency meeting just two weeks earlier. Kate Stenarude, Jack Taylor, Nelson Mumford, Kirk Weir, and Don Shilling—five of Lou’s six key executives—were standing in their places at the Zagrum Company’s boardroom table, giving Lou an earful. They were leaving, they told him, unless Lou gave them more space to run their organizations. They called him a meddler, a micromanager, and a control freak. One of them (Jack Taylor, Lou vowed never to forget) even painted Lou a tyrant.

Lou had listened to all of it in silence, not even looking into their faces. But he was burning inside. Ingrates! he had growled to himself. Incompetent, bumbling, turncoat ingrates!

“Get the hell out then!” he had finally yelled. “If the standards here are too high for you, then you’d better leave now because they’re not coming down!”

“We’re not talking about the standards, Lou,” Kate had pleaded. “We’re talking about the atmosphere of oppression we’ve come to work under. The ladder thing you just pulled on me, for example.” She was referring to how Lou had recently removed a ladder from the sales team area, an act that symbolically undercut her attempt to implement a new incentive system in her department. “It’s a small thing, but it speaks volumes.”

“It’s only oppressive for those who can’t measure up to the standards, Kate,” he spat back, ignoring her specific complaint. “And honestly, Kate, after all I’ve done for you.” He shook his head in disgust. “You owe everything you’ve become here to me, and now look at you.” He curled up his lip as if he would spit the whole lot of them out of his mouth if he could. “I would have expected more out of you.

“So get out then! All of you. Get the hell out!”

The March Meltdown, as this interchange and subsequent defection had come to be called around the halls of Zagrum Company, had nearly ground Zagrum’s work to a halt over the last two weeks. Lou was worried about his company’s future.

“Viewed economically,” Avi continued, pulling Lou back to the present, “this is an insane strategy. But we do it anyway. In fact, it’s almost like we feel compelled to do it. We can get ourselves in a position where we compulsively act in ways that make our own lives more difficult—by stoking the fires of resentment in a spouse, for example, or anger in a child. But we do it anyway. Which leads us to the first reason why way of being is so important: when our hearts are at war, we can’t see clearly. We give ourselves the best opportunity to make clear-minded decisions only to the extent that our hearts are at peace.”

Lou thought about that as he pondered his decisions regarding Kate and the others who had left him.

“Here’s another reason why way of being is so important,” Avi continued. “Think about the negotiation situation again. The most successful negotiators understand the other side’s concerns and worries as much as their own. But who is more likely to be able to consider and understand the other side’s positions so fully—the person who sees others as objects or the person who sees them as people?”

“The one who sees people,” Ria answered. Pettis and most of the others nodded in agreement.

“I think that’s right,” Avi said. “People whose hearts are at war toward others can’t consider others’ objections and challenges enough to be able to find a way through them.”

Lou thought of the impasse with the union.

“Finally,” Avi said, “let me add a third reason why way of being is important. Think about your experiences over the last few years with the children you have brought to us. Have you ever felt like they reacted unfairly to you even when you were bending over backwards to be kind and fair to them?”

Lou’s mind drifted back to an exchange he and Cory had had just two mornings earlier. “So it’s all my fault, right Dad?” Cory had bellowed sarcastically. “You’re the great Lou Herbert who has never made a mistake in his life, right?”

“Don’t be a child,” Lou remembered responding, proud that he was able to remain so calm in the face of such disrespect.

“It must be pretty embarrassing having a son like me—an addict, a thief. Right?”

Lou didn’t say anything, and he congratulated himself for rising above the moment. As he thought about it, however, he had to admit Cory was right. Lou was distinctly proud of his two older children—Mary, twenty-four, a PhD candidate at MIT; and Jesse, twenty-two, a senior at Lou’s alma mater, Syracuse University. In comparison, he found Cory embarrassing. That was true.

“Well, let me tell you something, Daaaad,” Cory had continued, sarcastically drawing out the word for emphasis. “Being the son of Lou Herbert is a living hell, to tell you the truth. Do you know what it feels like knowing that your dad thinks you’re a loser?

“Yeah, I know you’re thinking, ‘but you are a loser.’ I’ve been hearing that from you for years. I was never as good as Mary or Jesse. At least, not to you. Well, let me tell you something. You’re not as good as Mom, or any other adult I know, for that matter. You’re a bigger loser as a parent than I’ll ever be as a son. And you’re just as much of a disaster at work. Why else would Kate and the others have walked out on you!”

This exchange had once again showed Lou that treating Cory civilly got him nowhere. Cory disrespected him whether Lou yelled or stayed silent.

“I’m going to suggest something to you about this,” Avi continued, pulling Lou and the others back from their thoughts. “It’s an idea you might want to resist at first, especially regarding your children. But here it is: Generally speaking, we respond to others’ way of being toward us rather than to their behavior. Which is to say that our children respond more to how we’re regarding them than they do to our particular words or actions. We can treat our children fairly, for example, but if our hearts are warring toward them while we’re doing it, they won’t think they’re being treated fairly at all. In fact, they’ll respond to us as if they weren’t being treated fairly.”

Avi looked at the group. “As important as behavior is,” he said, “most problems at home, at work, and in the world are not failures of strategy but failures of way of being. As we’ve discussed, when our hearts are at war, we can’t see situations clearly, we can’t consider others’ positions seriously enough to solve difficult problems, and we end up provoking hurtful behavior in others.

“If we have deep problems, it’s because we are failing at the deepest part of the solution. And when we fail at this deepest level, we invite our own failure.”