“Look around the room,” Avi invited once more. “Who would you want to gather with and talk to if we were to take a break? Go ahead,” he invited. “Look around.”

Gwyn glanced furtively at Ria and Carol. Miguel looked quickly at Lou, but then turned away when Lou turned to him. Lou looked inquiringly at Elizabeth, but she didn’t acknowledge him. She seemed not to want to be included in this pairing off.

“And what would you be likely to talk about with these people?” Avi asked.

There was a silence in the room, but eyes darted here and there, and it was clear to Avi that the group was responding silently to his question.

“Gwyn,” Avi said, interrupting the silence, “if I might be so bold as to ask, Who in the room would you most like to talk to, and what do you think your conversations might be about?”

“Oh, probably Ria, I’d say. And maybe Carol. And what would we talk about? About their husbands I’d imagine,” she answered, with a wry smile.

“And what about their husbands?” Avi asked.

“Whether they’re always so bigoted or only when they’re in public.”

Avi butted in before Lou could fire back.

“Notice what’s happened here,” Avi said. “Gwyn ends up talking with Ria and Carol. And about what? About how they are each being treated unfairly or unjustly by someone else. We end up gathering with allies—actual, perceived, or potential—as a way of feeling justified in our own accusing views of others.

“As a result of this fact, conflicts try to spread.”

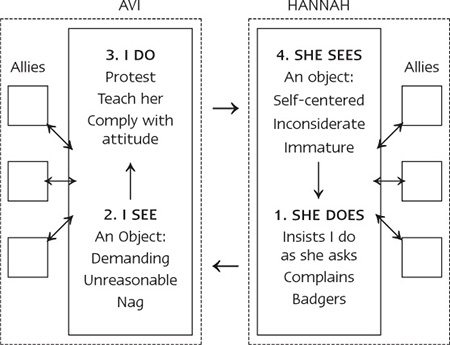

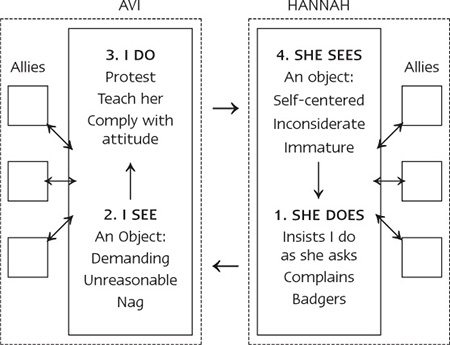

Adding more boxes to the diagram on the board, he said, “Like this.”

THE COLLUSION DIAGRAM

“So what begins as a conflict between two people spreads to a conflict between many as each person enlists others to his or her side. Everyone begins acting in ways that invite more of the very problem from the other side that each is complaining about! We have seen it happen here in this room in the last few minutes. It certainly happened that way in my home as Hannah and I found ways to recruit our children into the fray. I would conspicuously roll my eyes, for example, when Hannah demanded something of me. And I would commiserate with the children when I thought she was coming down too hard on them. I recruited my kids into feeling mistreated like I felt.”

“That’s sick,” Gwyn said.

“Yes,” Avi agreed, “it is.

“And I would wager a mighty sum,” he continued, “that your respective organizations look like this as well—with workers recruiting colleagues and others with the tales they tell, leading to organizations that are divided into warring silos, one group complaining incessantly about another, and the other returning the same. Until finally, your organizations are filled with people whose energies are largely spent on sustaining conflict—what we call collusion—and who therefore are not fully focused on achieving the productive goals of the organization.

“Am I right?” Avi asked with emphasis.

Although he didn’t say anything, Lou had to admit that he saw this pattern in spades at Zagrum. He could also see himself and Cory spinning in the same kind of circle. The harder he was on Cory, the more Cory rebelled, and the more Cory rebelled, the more Lou bore down on him. Lou didn’t roll his eyes like Avi did, but he gathered allies by complaining about Cory to Carol and others.

“It seems to me like many world-level conflicts are collusions as well,” Elizabeth spoke up. “The conflict in my region of the world in Northern Ireland, for example. Both sides are inviting the very things they’re fighting against.”

“It’s the same way in the conflict between Israelis and Palestinians,” Avi agreed. “In fact,” he continued, “the concept of collusion explains how an ancient personal conflict now threatens the entire world. Consider the story of Abraham and his sons, Isaac and Ishmael. These sons, in accordance with decrees attributed in scripture to God, became fathers of nations—Isaac the father of the Israelite people and Ishmael the father of the Arab people. As such, these men hold special places in the belief systems of Jews, Christians, and Muslims the world over.

“Jews and Christians, for their part, believe that Isaac was the chosen son with specific rights granted to him and his posterity, including rights to the land. They believe that God told Abraham to offer Isaac as a sacrifice as a test of Abraham’s faith. According to the Old Testament, this sacrifice was to take place on a hill ‘in the land of Moriah’—a location in present-day Jerusalem. Centuries later, King Solomon constructed a temple on a hill in Jerusalem believed to be the location of this event, a mount known as Mount Moriah—the mountain after which Camp Moriah is named. In modern times, this mount is capped by the Al Aqsa Mosque complex, originally constructed by the Muslims after the initial conquest of Jerusalem that we talked about earlier. The world-famous shrine known as the Dome of the Rock, located within the thirty-five-acre complex, occupies the spot from where Muslims believe the prophet Mohammed ascended to heaven in a nocturnal vision. It is also believed to be the place of the experience between Abraham and his son.

“Which brings us to Ishmael.

“Although the Koran does not tell us one way or the other, many Muslims believe it was Ishmael, not Isaac, that Abraham was commanded to sacrifice on Moriah. Muslims also believe that Ishmael, rather than Isaac, was the chosen son. And finally, they believe it was Ishmael, not Isaac, who was given the right to the land. And so we have a dispute between brothers—those who believe Isaac was the chosen son and those who look to Ishmael as the chosen one. Descendants of each believe that they have claim to the land and to the heritage and primary blessings of the prophet Abraham.”

Avi pointed at the Collusion Diagram. “You could substitute Isaac for my name and Ishmael for Hannah’s and the diagram would be equally true of that conflict. Believers on each side now provoke the very mistreatment from the other that they are complaining about.”

“But what if one of the views is the correct one, Avi?” Lou interjected. “Are you suggesting that all parties in a conflict are equally in the wrong, even if one side’s claims are patently false?”

“And which side’s claims are patently false here, Lou?” The heads of the group whipped around. It was Yusuf, who had slipped back into the room unnoticed a minute or two before.

“Well, Yusuf,” Lou answered, after resizing him up for a moment, “I would say that yours are.”

“Mine?”

“Yes.”

“And which claims would mine be?”

Lou instantly regretted the presumptuousness that left him open to such an easy counter. “Well, I guess I don’t know what your individual views are, exactly, Yusuf,” he said, trying to cover the crack left exposed by his earlier answer. “I was speaking rather of your people’s views.”

“Oh? And what people would that be?”

“Ishmael’s descendants,” Lou answered with a forced nonchalance. “The Arab people.”

Yusuf nodded. “Another characteristic of conflicts such as these,” he said, gesturing toward the board, “is the propensity to demonize others. One way we do this is by lumping others into lifeless categories—bigoted whites, for example, lazy blacks, crass Americans, arrogant Europeans, violent Arabs, manipulative Jews, and so on. When we do this, we make masses of unknown people into objects and many of them into our enemies.”

“I’m not making anyone into my enemy, Yusuf. I’m merely naming those who have declared me to be their enemy.”

“And all Arabs have done this?” Yusuf asked. “And they have named you, Lou Herbert, as their enemy?”

At first, Lou was beaten back by this question, but then he leaned back in his chair, a sudden air of rediscovered confidence dancing in his eyes. “Why do you insist on changing the subject?”

“I don’t think I have, Lou.”

“Oh yes you have,” Lou countered. “You keep answering my questions with unrelated questions. You don’t want to go where my questions are directed, so you create mirages elsewhere.”

Yusuf didn’t say anything.

“I’ll tell you what, Yusuf. I’ll answer your questions after you answer mine.”

“Fair enough,” Yusuf said. “What would you like me to answer?”