“I was raised,” Yusuf began, “in a village of rock-walled homes in the hills on the western edge of Jerusalem. The village, called Deir Yassin, had been my family’s home for at least two centuries. But that all ended early on the morning of April 9, 1948, at the height of the Arab-Jewish fighting surrounding the establishment of Israel. I was just five years old at the time. I remember being awakened by shouting and gunfire. Our village was being attacked by what I later learned were members of a Jewish underground military group. My father grabbed me from bed and thrust me and my two sisters into my parents’ room. He then pulled a rifle from under his mattress and, pulling on his boots, ran out of the house. ‘Stay inside!’ he yelled to us. ‘Don’t come out for anyone, you hear? Until I return, God willing.’

“Those were the last words I ever heard my father speak. When it was over and we left the protection of our stone walls, bodies and exploded body parts littered the streets. My father was among the dead.”

“How terrible,” Ria said.

“It was many years ago,” Yusuf responded. “Those days and the years that followed were difficult for me and my family, I won’t deny it. But we weren’t the only ones that suffered tragedy.”

Elizabeth spoke up. “I was going to say, I have some Jewish friends that have similar stories to tell.”

“I’m sure you do,” Yusuf said, “as do I. A Jewish village called Kfar Etzion was attacked by Arab forces at around the same time, for example. The entire village was basically massacred, so I can hardly say that my fate was worse than theirs. By telling my story, I did not mean to imply that Arabs are the only ones that have suffered unjustly. I’m sorry if it seemed that way. Avi’s father, for example, was killed while defending his country against an Arab attack. That hurt him as much as losing my father hurt me. Over the years and centuries, violence has been hurled hatefully in all directions. That is the tragic, bloody truth.”

Lou was glad to hear Yusuf own up to Arab atrocities, but he felt uneasy all the same. It seemed to Lou that Yusuf was too quick to equate Arab and Israeli suffering when in Lou’s mind the scales of unjustified suffering clearly leaned in the Israeli direction. Lou wasn’t sure, but he thought he might have an ally in this belief in Elizabeth Wingfield.

“After my father died,” Yusuf continued, “my mother moved us from village to village until we finally found refuge in Jordan. We settled in a refugee camp in a town called Zarqa, which is on the northwest side of the city of Amman. When Jordan annexed the West Bank following the War of 1948, known in Israel as the War of Independence, my mother moved us back to the west side of the Jordan River. We moved to the town of Bethlehem, which is only a few miles from Deir Yassin.

“As I look back now, and put myself in my mother’s place, it was bold of her to return so close to the place of her personal tragedy. Years later she told me that she felt compelled to return as close to her roots as she could. We took up residence in Bethlehem with her sister—my aunt, Asima.

“The economy of Bethlehem, such as it was, depended largely on Christians who made pilgrimages to the historical birthplace of Jesus. The war severely reduced the number of visitors, so merchants were hard up for customers. I was hired as a street hustler at the age of eight. My job was to make Westerners feel sorry for me and then lead them to the shops of the people who had hired me. In broken English, I began to interact with the West.

“As for the Jews, I had little opportunity or desire to interact with them. The Jews had been expelled from the West Bank after Jordan annexed it. Border penetrations from both directions, whether for military or economic reasons, usually ended in gunfire and casualties. The Jews were our enemies.

“At least, this is the simplistic picture most often recited and remembered. The truth was a bit more nuanced. I know because I worked the same streets as a certain blind Jewish man, appealing to the same Western wallets for the same Western money.

“Which brings me to the story I want to share with you. I had come to know this man, Mordechai Lavon, at what you might call a close distance. We often worked the streets within mere feet of each other, and although I was well acquainted with his voice and he with mine, I had never once addressed him, even though he tried to strike up a conversation on occasion.

“One day, he stumbled as he asked a passerby for help. His purse burst open as it hit the ground, and his coins flew in all directions into the street.

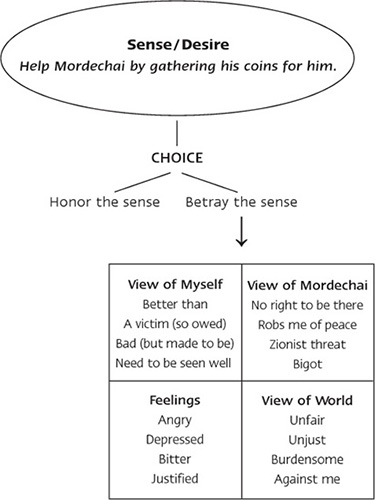

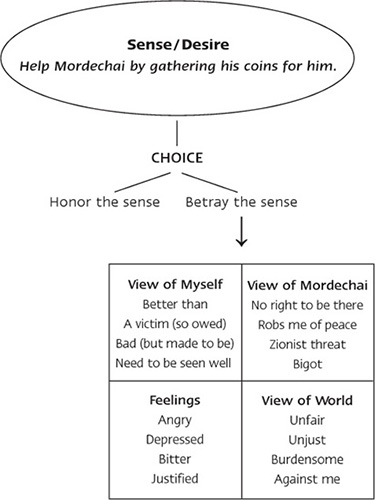

“As his hands groped first for his purse and then in search of the individual coins, I had a sudden thought. You might call it a sense of something to do, something I knew in that instant was the right thing to do. I think it would be accurate, in fact, to call it a desire. That is, I felt a desire to help him—first to help him to his feet and then to retrieve his coins for him.

“I had a choice, of course. I could act on this sense I had, or I could resist it. Which do you suppose I did?”

“I’d imagine you helped,” Carol said.

“No he didn’t,” Lou smirked. “He wouldn’t be telling the story if he had.”

Yusuf smiled. “True enough, Lou. You’re right. I resisted the sense I had to help Mordechai. A stronger way to say it is that I betrayed that sense and acted contrary to what I knew was right in that moment. Instead of helping, I turned and walked the other way.”

Continuing, he said, “As I was walking away, what sorts of things do you suppose I might have started to say and think to myself about Mordechai Lavon?”

“That he shouldn’t have been there anyway,” Gwyn responded. “You and the rest of your neighbors were kind to allow him to stay. After all, he was one of the enemy, who robbed you of your peace. A Zionist threat. A bigot.”

“Hmm,” Elizabeth began, in a puzzled tone, “who was the bigot?”

“I’m not saying Mordechai was a bigot,” Gwyn answered.

“Neither am I,” Elizabeth agreed.

“Oh, I see,” Gwyn said. “I’m the bigot, then. Is that what you’re saying?”

“I don’t know, I was just asking,” Elizabeth said, coolly.

“Look, Elizabeth, Mordechai may or may not have been a bigot. Who knows? I’m just saying that Yusuf probably saw him that way, and his people too. That’s all. Is that a problem?”

“Not at all. Thank you,” Elizabeth said as she looked down at her lap and straightened a crease in her skirt.

“Sure. And thank you to the Brits for dividing Mordechai’s and Yusuf’s lands in the first place. With a little help from the French, of course. That helped a lot.”

The air was suddenly electric. Lou leaned forward to get a good look at what would happen next.

Elizabeth didn’t say anything for a moment. “History has certainly called those events into question, hasn’t it?” she finally said, with no hint of venom in her voice. “Sorry to have tweaked you with the bigot remark, my dear. It was a bit forward. I’d say it was almost American of me, but that would expose me too fully, wouldn’t it?” She smiled demurely.

The charge seemed to leave the air as quickly as it had come.

“No, we wouldn’t want to be American now, would we?” Gwyn smiled.

“Heaven forbid,” Elizabeth cracked.

“For a moment, I thought I might have to put Lou between the two of you,” Yusuf said, eliciting a roar of laughter from the group.

“What’s so funny?” Lou deadpanned.

Amid the laughter, on the whiteboard Yusuf wrote, “No right to be there,” “Robs me of peace,” “Zionist threat,” and “Bigot” to summarize the ways he was seeing Mordechai.

“Okay then,” Yusuf said after he finished writing, “if I was starting to see Mordechai in these ways we’ve mentioned, how do you suppose I might have started to see myself?”

“As a victim,” Pettis answered.

“And as better than he was,” Gwyn said.

“I don’t know,” Carol spoke up, “you might have gotten down on yourself—like you weren’t good enough. Deep down, I think you would have felt like you weren’t being a very good person.”

“Maybe so,” Gwyn agreed, “but it wasn’t his fault, after everything that had happened. If he was bad, it was because of what others had done to him.”

“I don’t know,” Lou disagreed. “That sounds like a cop-out.”

“We’ll get to whether it’s a cop-out,” Yusuf stepped in. “But I think what Gwyn said certainly describes what I was at least believing to be the case at the time.”

“Okay,” Lou allowed.

“What else?” Yusuf asked.

“I’m thinking about how you walked away after you noticed the coins,” Pettis answered. “On the one hand, I can see how a feeling of victimization would invite you to walk away. But I think there could have been another motivation as well.”

“Go on,” Yusuf invited.

“Well,” Pettis responded, “I’m thinking that by turning quickly away, you were giving yourself an excuse. Your turn away might have been out of a need to be seen as a good person.”

“What do you mean?” Lou asked. “If he turned away, how does that make him a good person?”

“It doesn’t,” Pettis answered. “But it makes it easier for him to claim that he is. If he didn’t need to be seen as being good, he could have just stood and watched Mordechai struggle. But by quickly turning away so it seemed like he didn’t see the situation, he preserved his reputation—his claim of goodness.”

Yusuf started to chuckle. “That’s a really interesting insight, Pettis. It reminds me of something that happened just this morning. I was making myself a sandwich, and I noticed that I’d dropped a piece of lettuce on the floor. It would have been easy to bend over and pick it up, but I didn’t. Instead, I pushed it under the counter with my toe! I wouldn’t have had to do that unless I was concerned with showing my wife, Lina, that I was a good person—tidy, responsible, and so on. Otherwise, I might have just left it there.”

“Well why not just pick it up?” Gwyn objected. “Honestly!”

“Yes,” Yusuf agreed. “And why not just pick up the coins too? That’s exactly the question we’re beginning to explore.”

At that he added “Need to be seen well” to the list he was constructing on the board.

“Okay then,” he said, as he turned back to the group. “When I’m seeing this man and myself in the ways we’ve discussed, how do you suppose I might have viewed the circumstances I found myself in?”

“As unfair,” Gwyn answered.

Yusuf started writing that on the board.

“And unjust,” added Ria.

“And burdensome,” said Pettis. “Given all you’d suffered, I can imagine you went around feeling angry or depressed.”

“Yes,” Elizabeth agreed. “In fact, you might have felt that the whole world was lined up against you—against your happiness, against your security, against your well-being.”

“Excellent. Thank you,” Yusuf said as he finished writing. “Now, I’d like to play off something Pettis just said—that I might have felt angry or depressed. Can you think of any other ways I might have felt given the way I was seeing everything else?”

“You would have been bitter,” Gwyn answered.

“Okay, excellent,” Yusuf said, adding “Bitter” to “Angry” and “Depressed” on the diagram. “But if you were to ask me why I was feeling those ways, what do you think I would have said?”

“That it wasn’t your fault,” Pettis answered. “You would have said it was the Israelis’ fault—that you felt that way only because of what they had done to you and your people.”

Yusuf nodded. “Which is to say that I felt justified in my anger, my depression, and my bitterness. I felt justified in my judgmental view of Mordechai.”

At this, he added the word “Justified” to the diagram. “That’s what my entire experience here was telling me,” he said, pointing at the board. “That I didn’t do anything wrong, and that others were to blame. That is what I was believing, was it not?”

View of Myself |

View of Mordechai |

Feelings |

View of World |

“Probably—” Pettis answered, giving voice to the prevailing thought in the room.

“That I wasn’t responsible for how I was seeing and feeling?” Yusuf followed up.

“Yes.”

“But is that true?” Yusuf asked. “Was I really caused by outside forces to see and feel in these ways—the way I believed when I was in this box here? Or was I rather choosing to see and feel in these ways?”

“You’re suggesting you were actually choosing to be angry, depressed, and bitter?” Gwyn asked incredulously.

“I’m suggesting I was making a choice that resulted in my feeling angry, depressed, and bitter. A choice that was my choice, and no one else’s—not Mordechai’s, not the Israelis’.”

Yusuf looked around at a room full of perplexed faces. “Perhaps it would help,” he said, “to put the diagram in context.” He then added the following:

THE CHOICE DIAGRAM

“As you’ll recall,” he began, “I had a sense or desire to help Mordechai. I knew it was the right thing to do. But this then presented a choice: I could either honor my sense to help or I could betray it and choose not to help. Which is to say that we don’t always do what we know is the right thing to do, do we?”

The group looked uncertain.

“For example,” Yusuf continued, “We don’t always apologize when we know we should, do we?”

Lou thought of the apology he still owed Kate.

“When a spouse or child or neighbor is struggling with something we could easily help with, we don’t always offer that help. And don’t we sometimes hold onto information we know we should share with others? At work, for example, when we know a piece of information would help a coworker, don’t we sometimes hold it for ourselves?”

Most in the group nodded their heads contemplatively, including Lou, who knew this scenario well.

“When I choose to act contrary to my own sense of what is appropriate,” Yusuf continued, “I commit what we at Camp Moriah call an act of self-betrayal. It is a betrayal of my own sense of the right way to act in a given moment in time—not someone else’s sense or standard, but what I myself feel is right in the moment.

“Acts of self-betrayal such as those I’ve mentioned are so common they are almost ho-hum. But when we dig a little deeper, we discover something fascinating about self-betrayal.”

He looked around at the group. “A choice to betray myself,” he said, “is a choice to go to war.”