“How is a choice to betray oneself a choice to go to war?” Lou asked, troubled by the claim.

“Because when I betray myself,” Yusuf answered, “I create within myself a new need—a need that causes me to see others accusingly, a need that causes me to care about something other than truth and solutions, and a need that invites others to do the same in response.”

“What need is that?” Pettis asked.

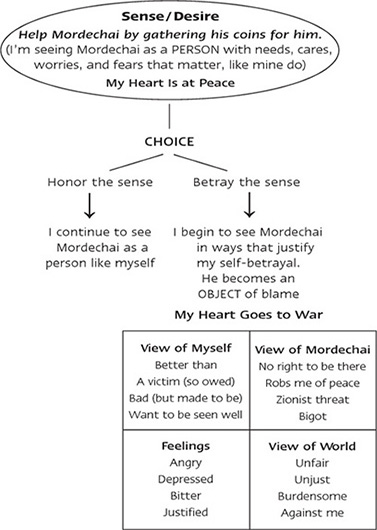

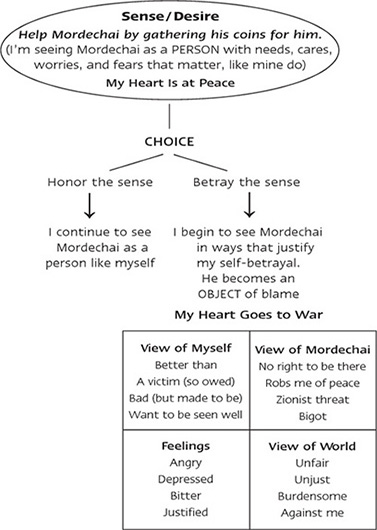

Yusuf turned back to the Choice Diagram. “At the beginning here, when I had the desire to help Mordechai, how would you say I was seeing him? Was he a person or an object to me?”

The group collectively murmured, “He was a person.”

“How about down here at the end, when I was in this box. Was he still a person to me then?”

They looked at the diagram.

Pettis spoke up. “No, you’d dehumanized him. He’s almost a caricature.”

“So what was he to me at that point, a person or an object?”

“An object,” Pettis answered.

“Which gives rise to what need?” Yusuf asked.

Pettis and the others puzzled over that. “I’m not sure what you mean,” he said.

“Perhaps an analogy would help,” Yusuf responded. “My father was a carpenter. When I was four or five, I remember going with him on a job where he was helping to rebuild a house. I remember in particular a wall in the kitchen area of the home. It turned out that the wall was crooked. I remember this because of something my father taught me about it. ‘Here, Yusuf,’ I remember him saying, although in Arabic, of course, ‘we need to justify this wall.’

“‘Justify, Father?’ I asked.

“‘Yes, Son. When something is crooked and we need to make it straight, we call it justifying. This wall is crooked, so it needs to be justified.’”

With that, Yusuf looked around at the group.

“With that story as an analogy,” he said, “take another look at the diagram.”

Carol’s quiet voice came in immediate reply. “You needed to be justified in the story,” she said. “That’s the need you’re talking about, isn’t it?”

“Yes, Carol,” Yusuf smiled, “it is. And did I have any need to be justified when I had the desire to help Mordechai?”

“No.”

“Why not?”

“Because you weren’t being crooked toward him in that moment.”

“Exactly,” Yusuf agreed, landing heavily and happily on the word. “Did everyone catch that?” he asked the group.

Heads nodded around the room, but not convincingly enough for Yusuf’s taste.

“Let’s be really clear on this,” he said. “What was crooked when I turned my back on Mordechai that wasn’t crooked before?”

“Your view of him,” Carol answered.

“Yes,” Yusuf agreed. “And what was crooked about that view of him?”

“You weren’t seeing him as a person any longer,” Pettis answered. “He didn’t count any more. At least not like you counted.”

“Exactly. In fact, it was precisely because I was seeing him as a person at the beginning of the story that I wanted to help him. But the moment I began to violate the basic call of his humanity upon me, I created within me a new need, a need that didn’t exist the moment before; I needed to be justified for violating the truth I knew in that moment—that he was as human and legitimate as I was.

“Having violated this truth, my entire perception now raced to make me justified. Think about it. When do you suppose Mordechai’s personal quirks, whatever they might have been, seemed larger to me, before I betrayed my sense to help him, or after?”

“After,” the group answered.

“And when do you suppose the group I lumped Mordechai in with, the Israelis, seemed worse to me? In the moment I had the sense to help Mordechai, or after I failed to help him?”

“After,” the group repeated.

“So notice,” Yusuf continued, “when I betray myself, others’ faults become immediately inflated in my heart and mind. I begin to ‘horribilize’ others. That is, I begin to make them out to be worse than they really are. And I do this because the worse they are, the more justified I feel. A needy man on the street suddenly represents a threat to my very peace and freedom. A person to help becomes an object to blame.”

At this, Yusuf turned to the board and added to the diagram they were discussing. As he was finishing, Gwyn asked, “But what if Mordechai really was a problem? What if he wasn’t some gentle blind man but an out-and-out racist jerk? What if he outwardly agreed with the people who had thrust your family from your home? Wouldn’t you be justified in that case?”

“What need would I have to be justified if I wasn’t somehow crooked?” Yusuf asked, turning from the board to face the group.

Gwyn was clearly frustrated by that answer. “I’m sorry, Yusuf,” she said, “but I don’t know if I can accept that. It seems like you’re just giving bad people a pass.”

Yusuf’s eyes seemed to soften at this comment. “I appreciate how seriously you are grappling with this, Gwyn,” he said. “I am wondering if you would be willing to grapple with another question just as seriously.”

“Maybe,” she answered pensively.

Yusuf smiled. Being reflexively cynical himself, he appreciated those who listened with a healthy dose of careful skepticism. “You are worried that I might be giving Mordechai a pass, that I might not be holding him accountable for wrongs he or his clan have perpetrated. Am I right?”

Gwyn nodded. “Yes.”

“There is a question I have learned to ask myself, Gwyn, when I am feeling bothered about others: am I holding myself to the same standard I am demanding of them? In other words, if I am worried that others are getting a pass, am I also worried about whether I am giving myself one? Am I as vigilant in demanding the eradication of my own bigotry as I am in demanding the eradication of theirs?”

He paused a moment to let that settle.

“If I’m not, I will be living in a kind of fog that obscures all the reality around and within me. Like a pilot in a cloud bank whose senses are telling him just the opposite of what his instrument panel is saying, my senses will be systematically lying to me—about myself, about others, and about my circumstances.” Focusing clearly on Gwyn and capturing her gaze, he added, “My Mordechais may not be as prejudiced as I think they are.”

“Yours may not be,” Gwyn challenged him. “I wouldn’t know. But mine are.”

Yusuf looked thoughtfully at Gwyn. “You may be right,” he said, a touch of resignation in his voice. “Your Mordechais might be prejudiced. Some people are, after all. And to the larger point, you might have suffered some terrible mistreatments at others’ hands. All of you who are parents here, for example,” he said, looking around the semicircle, “have undoubtedly been treated terribly at times—unjustly, unfairly, ungratefully. Right?”

Heads nodded.

“And you may have been railroaded at work as well— blamed, overlooked, unappreciated. Or perhaps you have been mistreated by society generally. Maybe you belong to a religion that you feel is treated prejudicially, or to an ethnic group that you feel is systematically disenfranchised, or to a class that is ignored or despised. I know a thing or two about each of these mistreatments. I know what they feel like, and I know how terrible they are. I can say from experience that there are few things so painful as contempt from others.”

“That’s right,” Gwyn readily agreed. Others nodded as well.

“Few things except one,” Yusuf continued. “As painful as it is to receive contempt from another, it is more debilitating by far to be filled with contempt for another. In this too I speak from painful experience. My own contempt for others is the most debilitating pain of all, for when I am in the middle of it—when I’m seeing resentfully and disdainfully—I condemn myself to living in a disdained, resented world.

“Which brings me back to Mordechai,” he said. “Would you say I was filled with resentment or contempt when I had the sense to help him?”

The group looked back at the diagram.

THE CHOICE DIAGRAM

“No,” Ria answered, followed by the others saying the same thing.

“But how about at the end of the story,” Yusuf asked, “when I was down in this box seeing him as a bigot and Zionist threat? Was I feeling resentful then?”

The group looked at the feelings that were listed in the box: angry, depressed, bitter, justified. “Yes,” they nodded.

“So why was I feeling that way?” Yusuf asked. “I had certainly suffered my share of hardships. Was that the cause of my bitterness, my anger, my resentment, and my contempt?”

“Probably,” Gwyn answered.

“Look at the diagram again,” Yusuf said.

“No,” Pettis answered, “your hardships did not cause your feelings.”

“Why do you say that?” Yusuf asked.

“Because whatever hardships you had suffered you had already suffered at the beginning of this story. But those hardships didn’t prevent you from seeing Mordechai as a person when you felt the desire to help him with his coins.”

“Exactly,” Yusuf said. “So what’s the only thing that happened between the time at the beginning of this story when I wasn’t feeling angry and bitter and the time at the end when I was? What’s the only thing that happened between the time that I saw Mordechai as a person and the time I saw him as an object?”

“Your choice to betray yourself,” Pettis answered.

“So what was the cause of my anger, my bitterness, my resentment, my contempt, my lack of peace? Was it Mordechai and his people? Or was it me?”

“Well, the diagram says it was you,” Lou answered.

“But you’re not convinced.”

“No, I’m not sure that I am,” Lou said. “Look, isn’t it possible you simply had a momentary lapse of memory when the coins spilled from Mordechai’s purse, a moment when your hardships weren’t foremost on your mind? It seems to me that’s what likely happened. And then a moment later you came back to reality and remembered all the trouble you’d suffered at the hands of the Israelis. It’s not like your bitterness just started in this moment. You’d felt it before. And you might have felt it, like Gwyn said, because of what the Israelis had done to you and your family.”

“What, you’re siding with me now?” Gwyn asked in jest.

“I know. It has me worried too,” Lou smirked.

Yusuf smiled. “That’s a great question, Lou. You’re right, of course, that this wasn’t the first time I had felt angry and bitter toward the Israelis. And you are right as well when you imply that my father’s death, and the hardships it caused my family, certainly played a role. But I believe it played a different role than the one you are suggesting. You seem to be saying that I ended up feeling the way I did about Mordechai because of what his people had done to me and my family. In other words, the hardships I had suffered caused the feelings I came to have about Mordechai. Is that what you are suggesting?”

“It’s what I’m wondering, anyway. Yes.”

“And I’m proposing something entirely different,” Yusuf responded. “I’m suggesting that my feelings about Mordechai were not caused by something others had done to me but by something I was doing to Mordechai. They were the result of a choice I was making relative to Mordechai. So,” he continued, “how shall we evaluate these very different theories?” He looked around at the group.

“I don’t know about evaluating them,” Elizabeth said, “but Lou’s theory leads to a pretty depressing outcome.”

“Which is what?” Yusuf asked.

“That we’re all just victims, powerless in the face of difficulty, inevitably doomed to be bitter and angry.”

“I’m not saying that,” Lou disagreed.

“I think you are,” Elizabeth countered. “You said the only reason Yusuf wasn’t bitter at the beginning of the story was because he simply wasn’t thinking about his hardships for a moment. Remembering them caused him to feel bitter and angry again. If that doesn’t make one powerless in the face of hardship, I don’t know what does.”

Lou had to admit she had a point. He didn’t believe in that kind of helpless victimhood either. He knew of too many great souls who had passed through terrible mistreatment without becoming embittered by it to believe that mistreatment left us without choices. But it does have an impact, doesn’t it? he wondered to himself, thinking of Cory.

“Excellent points, Elizabeth,” Yusuf said. “I’d like to continue with your idea if I might.”

“Certainly.”

Yusuf looked around at the group. “Not having a memory at the forefront of my mind is different than having forgotten it. I can assure you that there has never been a moment in my life since my father’s death that I haven’t remembered that he died and how he died. Having said that, Lou is right that the level and nature of my focus is often very different from moment to moment. Lou reasoned that that fact allowed me to see Mordechai differently in the moment I had the inclination to help him. Actually, however, Lou’s theory has it exactly backwards. It isn’t that I saw Mordechai as a person because I wasn’t dwelling on my hardships. Rather, it was that I wasn’t dwelling on my hardships because I was seeing Mordechai as a person. I needed to dwell on my hardships only when I needed to be justified for treating Mordechai poorly. My hardships were my excuse at that point. When I didn’t need an excuse, I was free not to dwell on them.”

“Oh, so an abused woman is at fault for hating her abuser?” Gwyn mocked. “I’m sorry if I can’t go there.”

Yusuf paused and took in a deep breath. “I couldn’t go there either, Gwyn,” he said. “May I share a story with you?”

Gwyn didn’t respond. Yusuf took a piece of paper out of a folder on a table in the front corner of the room. “This is from a letter I received in the mail a few years ago,” he said. “It was written by one of our former students here who had fallen on very difficult times in her marriage. Rather than try to give you the context for it, I will let her speak for herself.” He began reading.

One Friday more than a year ago, my estranged husband came to visit me at my parents’ home. He came over relatively frequently, ostensibly to visit our daughter but really to try to win me back. Shortly before he left on this particular day, he asked me to show him a copy of our life insurance policy. He asked if we were paid up on it and asked me to double-check his reading of a phrase in the suicide clause. By the time I closed the door behind him that evening, his intentions were obvious. David was going to commit suicide. I said good-bye, expecting that I would never see my husband alive again.

I could hardly contain my excitement.

You see, my charming young groom had become violent shortly after our marriage. Within months, I had grown so terrified of him that I would not do anything, even turn on the television, without his approval. He was extremely jealous and soon forced me to throw away my address book, my high school yearbooks, and even pictures of my family. He threatened my life, humiliated me in public, flirted openly with other women, and finally reduced even our physical intimacy to violence.

All the while, he would occasionally show such amazing tenderness and remorse that for two years I could never bring myself to leave him. Finally, at the urging of our marriage counselor, I escaped to my parents’ home. With their love and support, I slowly began to pull away from the bonds of my attachment to David. But he, more and more urgently, tried to win me back. I feared him, yet at the same time I needed him; I felt unable to free myself from the relationship. All in all, I was overjoyed to think that my nightmare might finally be ended with his suicide.

I was heartbroken when he appeared again the next morning. He was very depressed and proceeded to tell me the events of the night before. He admitted he had been planning to kill himself. He had gotten pills from a friend and had waited until nighttime so that nobody would be able to find him. Then he had sat down to compose his suicide note and will. After he had typed a few lines, the power suddenly went out. There wasn’t even enough light for him to finish his note by hand. Without that sense of completion, he had been unable to go through with his plans. Then he told me that perhaps fate had interfered to keep him alive, and that this was a sign that he and I still belonged together.

As he told me this story, I felt fury. I had come so close to being rid of him, finally so close, and one tiny twist of fate had ruined it for me. I was still stuck with this cruel, unstable man, the man who had destroyed my confidence, who showed every intention of tormenting me the rest of my life. I had never before been so consumed with hate. My disappointment was so intense, I decided immediately what I would have to do. I knew, especially given his current emotional state, that if I handled the situation the right way he would likely try suicide again. So I opened my mouth to say, coldly, that I still thought he was a horrible monster and that I would never come back to him no matter what he did. I was about to say that I didn’t care if he lived or died and that if anything, I preferred him dead. I was prepared to be as cruel as necessary to drive him back to suicide.

But then I paused. I still raged with hate, but I paused. I saw how close I was to encouraging a human being to die and was shocked by how far I was willing to carry my hate. I looked at him and was suddenly struck by something— something I learned at Camp Moriah. I was struck by his personhood, his humanity. Here before me was a person. A person with incredible emotional problems to be sure, but a person nonetheless. With his own deep hurts. His own heavy burdens. He himself had been raised in an abusive environment, with very little love and almost no kindness.

These thoughts made me cry. To my surprise, however, these were not tears of despair but tears of compassion. After all, this was a man who had intended to end his life. I found myself putting my arm around him to comfort him. It’s a moment I still can’t fully comprehend. In spite of everything he had done to me, I was consumed with love. And most surprising to me of all, from that moment—the moment I began seeing David as a person—I was never again tempted to return to the relationship. I had thought loving David meant I had to stay. That’s partly why I had felt trapped. But it turned out in my case that being freed from the need for justification for not loving him is what allowed me to leave—and to do so compassionately and calmly, without the bitterness that could have burdened me for a lifetime.

Just as I learned at Camp Moriah, when I started seeing people, the world transformed around me. I now feel free—not just from an unhealthy relationship but from feelings that might otherwise have poisoned me. My life certainly would have been easier had I never married David. But I will always be glad I did not encourage him to die.

At that, Yusuf looked up from the letter. Clearing his throat, he said, “If someone is abused, my heart breaks for that person; what a cruel burden to have to carry. If I know such a person and he or she rages inside, should I be surprised? Of course not. Under such circumstances, I think to myself, Who wouldn’t?

“In the face of that question, however, I find great hope in stories like the one I just read to you. For such stories show me that it is possible to find peace once more, even when much of my life has been a war zone.

“Although nothing I can do in the present can take away the mistreatment of the past, the way I carry myself in the present determines how I carry forward the memories of those mistreatments. When I see others as objects, I dwell on the injustices I have suffered in order to justify myself, keeping my mistreatments and suffering alive within me. When I see others as people, on the other hand, then I free myself from the need for justification. I therefore free myself from the need to focus unduly on the worst that has been done to me. I am free to leave the worst behind me, and to see not only the bad but the mixed and good in others as well.

“But none of that is possible,” he continued, “if my heart is at war. A heart at war needs enemies to justify its warring. It needs enemies and mistreatment more than it wants peace.”

“Yuck,” Ria said under her breath.

“Yuck, indeed,” Yusuf agreed. “A high-ranking Israeli political leader once said to me, ‘we and our enemies are perfect for each other. Each of us gives the other reason never to have to change.’ Unfortunately, the same is true in our homes and workplaces. The outward wars around us start because of an inward war that goes unnoticed: someone starts seeing others as objects, and others use that as justification for doing the same. This is the germ, and germination, of war. When we’re carrying this germ, we’re just wars waiting to happen.”

“What can you do about it?” Carol asked.

“To begin with,” Yusuf responded, “we need to learn to look for the ways we’re needing to be justified.”