Avi yanked himself from the memory of his suicide attempts and looked squarely at Carol.

“So no, Carol,” he said, “my stuttering was not the cause of my problems. Rather, I carried a heart at war—a heart at war with others, myself, and the world. I had been using my stuttering as a weapon in that war and had gotten myself into a place where I was seeing and feeling crookedly and self-justifyingly. That was my problem. And I wasn’t able to find my way out of it until I found my way out of my need for justification.”

“How?” Carol asked, her voice barely more than a whisper.

Avi smiled at her. “That, Carol, will be our topic for tomorrow.”

“You’re going to leave it at that?” Lou asked Avi. “You just told us you tried to commit suicide twice and now we’re just going to leave for the evening?”

Avi chuckled. “You want to hear more about it?”

“Well, I don’t know,” Lou pulled back. “Maybe.”

“I’ll tell you more about it tomorrow,” Avi promised. “But in our last forty minutes or so this evening, I think it would be best to review what we’ve covered today. That way, we’ll come back tomorrow with a solid understanding.

“First of all,” he began, “we’ve talked about two ways of being: one with the heart at war, where we see others as objects, and the other with the heart at peace, where we see others as people. And you’ll remember that we learned that we can do almost any behavior, whether hard, soft, or in between, in either of these ways. Here are two questions for you then: If we can do almost any outward behavior with our hearts either at peace or at war, why should we care which way we are being? Does it matter?”

“Yes,” Carol answered. “It definitely matters.”

“Why?” Avi asked. “Why do you think it matters?”

“Because I’ve seen how a heart at war ruins everything.”

Avi waited for more.

Carol continued. “I’ve been acting outwardly nice toward our boy Cory ever since he started getting into trouble, but I’ve known that I didn’t really mean it. And this has done a couple of things to me. First of all, I think I have played into an I-deserve box that has me thinking I am being nothing but sweet and kind, and he’s just mistreating me and the rest of the family. And Cory can tell that’s how I’m feeling. I know because he’s called me on it many times. Although I always deny his accusations,” she added meekly.

“I think I’ve also spent most of the last few years feeling a gnawing guilt knowing that I’m not really loving Cory, even though I’ve been making it look like I do.” She paused for a moment, her eyes suddenly filling with tears. “And no good mother does that,” she choked, as she wiped the moisture away. She began to shake her head. “No good mother does that.” She hesitated again. “I think I’ve developed a worse-than box—that I’m a bad mom.”

“I think you’re being too hard on yourself,” Lou said. “The truth is Cory has been a terribly difficult boy. It’s not your fault.”

“It depends what you mean by that, Lou,” she said, regaining her composure. “I understand that I may not be responsible for the things he’s done. But I am responsible for what I’ve done.”

“Yes, but you’ve done nothing but good,” Lou offered. “I’m the one who’s been the jerk with him.”

“But Lou, don’t you see? We’re talking about something deeper than merely what I’ve done or haven’t done. Yes, I’ve cooked his meals and cleaned his clothes. I’ve stood there and taken his abusive language, and more. But that’s just on the surface. The point is that while I’ve been playing the part of the outward pacifist, my heart has been swinging at him. And at you,” she added, “for the way you outwardly war with him. I’ve been at war too, but just in a way that makes it seem like I’m not.”

“But who wouldn’t be, under the circumstances?” Lou countered. “At war, that is.”

“But that can’t be the answer, Lou! It can’t.”

“Why not?”

“Because then we’re all doomed. That’s to say that our entire experience, even our thoughts and feelings, are controlled and caused by others. It’s to believe that we’re not responsible for who we’ve become.”

“But damn it, Carol, don’t you see what Cory is doing? He’s making you feel guilty for stuff he’s doing. What about Cory being responsible?”

“But in the world you describe, Lou, he couldn’t be responsible. If we can’t be expected to react to a heart that’s at war with anything but warring hearts ourselves, how can we expect or demand that he act any differently to us, when our hearts too are warring?”

“But he caused it all!” Lou bellowed. “We’ve always given him everything he’s needed! It’s his fault! You’re about to let him off the hook and take it all upon yourself. I won’t allow it!”

Carol took in a deep breath and exhaled heavily, her body shuddering with deep hurt as she did so. She looked at her lap and then closed her eyes, her face drawn in pain.

Yusuf spoke up. “What are you afraid of, Lou?”

“Afraid? I’m not afraid of anything,” Lou said.

“Then what is it you feel you cannot allow?”

“I can’t allow my boy to get away with destroying my family!”

Yusuf nodded. “You’re right, Lou. You can’t.”

That was not the answer Lou had been expecting.

“But that is not what Carol is suggesting. She hasn’t said anything about letting Cory off the hook. She’s only been talking about not letting herself off the hook.”

“No, she’s sitting here blaming herself for things that are Cory’s fault.”

“Like what? Has she said that the drugs and the stealing were her fault?”

“No, but she’s saying that she’s been a bad mother, when the fact of the matter is that any halfway good son wouldn’t have ever made her feel that way.”

“And Cory didn’t, that’s her point,” Yusuf said.

“Didn’t what?”

“Didn’t make her feel that way.”

“Yes he did!”

“That’s not what I heard her say.”

Lou turned to Carol. “Look, Carol,” he began, “I know you’re upset, but I don’t want you to take on more than you are able. I don’t want you to internalize problems that aren’t yours, that’s all.”

Carol smiled at Lou, her face painted in melancholy. “I know, Lou. Thank you. But Yusuf’s right.”

“That I am responsible for how I have been feeling, not only for what I have been doing.”

“But you wouldn’t have been feeling that way if it wasn’t for Cory!”

She nodded. “You may be right.”

“See!” Lou pounced. “That’s what I mean.”

“Yes, I think I do see, Lou, but I’m afraid that you still do not.”

“What do you mean?”

“The fact that I wouldn’t have felt the way I’ve come to feel if it weren’t for Cory doesn’t mean he has caused me to feel as I have.”

“On the contrary, of course that’s what it means,” Lou objected.

“No, Lou, it doesn’t. And here’s how I know: I’m not feeling that way now. Cory has done everything he has done—everything he has done in the past, everything I have blamed for how I have been feeling—but I don’t feel the same now. Which means that he hasn’t caused me to feel how I’ve felt. I’ve always had the choice.”

“But he makes the choice difficult!” Lou objected.

“Yes,” Yusuf stepped in. “He likely does, Lou. But difficult choices are still choices. No one, whatever their actions, can deprive us of the ability to choose our own way of being. Difficult people are nevertheless people, and it always remains in our power to see them that way.”

“And then get eaten up by them,” Lou muttered.

“That’s not what he’s saying, Lou!” Carol pleaded. “Seeing someone as a person doesn’t mean you have to be soft. The Saladin story showed us that. Even war is possible with a heart at peace. But you know that, Lou. You’ve been here the whole time I have, and you’re a smart man. Which means that if these are really still questions for you, then you are refusing to hear. Why, Lou? Why are you refusing to hear?”

This rebuke caught Lou short. Normally, he would have pounced all over such a pointed comment and leveled the insufferable soul who had made it. But he had no such urge in the moment. Carol, ever meek, even timid, had perhaps never criticized him so directly. Certainly never in front of others. And yet here she was, countering Lou’s complaint that she was letting others off the hook by refusing to let Lou off the hook! Lou began to marvel that he was learning lessons on outward toughness from the most gentle person he knew. He had worried that this course would invite people to be weak and soft, and yet Carol seemed to be metamorphosing in the other direction right before his eyes. “Some justification boxes make people go soft,” Lou remembered. Maybe Carol has had those kind of boxes, he thought. And so maybe getting out of the box for her will invite her to be more forceful at times.

But that’s not my problem, he chuckled. If I’m in these boxes, they must be boxes that invite me to go hard—really hard, in fact. He chuckled again. So maybe getting out of them will mean that I will soften up some. Despite the epiphanies, that thought worried Lou.

“Lou,” came Yusuf’s voice, ripping him away from his thoughts. “Are you okay?”

“Yes, fine. I’m fine.”

He leaned over to Carol. “I think I may be recovering a bit of my hearing,” he whispered. I’ll be damned, he thought, I am going soft. But suddenly he wasn’t so worried about it.

“So—” Yusuf continued, looking around at the group. “In response to Avi’s question, Carol has suggested that the issue deeper than our behavior—our way of being—matters. A lot. Do you agree?”

Lou nodded along with the others.

“Then I have another question for you. If the choice of way of being is important, then how do we change from one way to the other? Specifically, how do we change from peace to war— from seeing people to seeing objects?”

“Through self-betrayal,” Elizabeth answered.

“Which is what?” Yusuf asked.

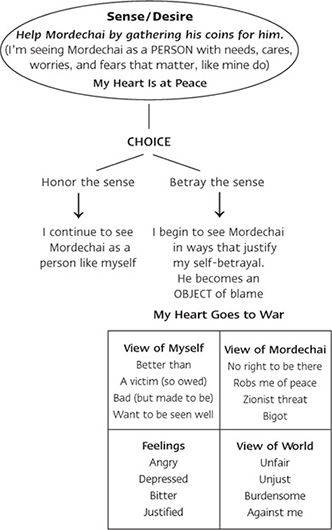

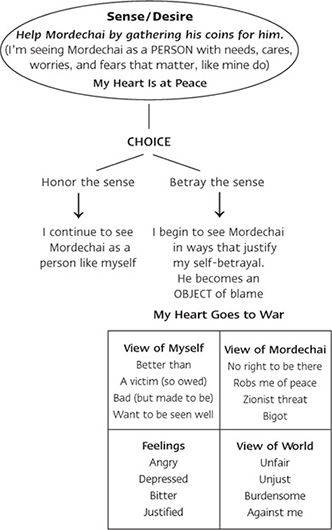

“It’s what you illustrated through the Mordechai story. You had a sense to help him, which means you were seeing him as a person, but then you turned away, and began to justify why you shouldn’t have to help him, and he became an object to you.”

“Yes, excellent, Elizabeth,” Yusuf said. “That is exactly right. So self-betrayal—this act of violating my own sensibilities toward another person—causes me to see that person or persons differently, and not only them but myself and the world also. When I ignore a sense to apologize to my son, for example, I might start telling myself that he’s really the one who needs to apologize, or that he’s a pain in the backside, or that if I apologize, he’ll just take it as license to do what he wants. And so on.

“Which is to say,” he continued, “that when I violate the sensibility I have about others and how I should be toward them, I immediately begin to see the world in ways that justify my self-betrayal. In those moments, I am beginning to see and live crookedly, which creates the need within me to be justified.”

“But what if I don’t have those impressions to help to begin with?” Lou asked. “I actually don’t think I have them very often, to tell you the truth. Does that mean I’m not betraying myself?”

“Perhaps” Yusuf allowed. “Yet it could mean something else.” “What?”

Yusuf pointed at the Choice Diagram.

THE CHOICE DIAGRAM

“What do you suppose happens,” he said, “if I get in this box here toward Mordechai and then don’t get out?”

No one responded for a moment.

“Nothing will happen,” Lou finally said. “Everything will stay the same.”

“Yes, Lou, which is to say that I will end up carrying that box with me, right?”

“Yes, I guess that’s right,” Lou responded slowly, trying to grasp the implications.

At that, Yusuf added an arrow to the diagram, signifying how the box can travel with us.

“In other words,” Yusuf resumed, “If I get in this box and don’t get out, I end up taking the box with me. And in my next interaction with Mordechai, I am likely to start in the box— from the very beginning, right?”

Yusuf waited to see comprehension in the eyes before him. Sensing that they were understanding, he continued. “And if I’m already starting in the box, do you suppose I would be likely to have a sense or desire to help in my next interaction with Mordechai or with others I lump together with him?”

“Oh, I see,” Lou said. “No, you wouldn’t. You would start out bothered and bitter and angry. And in that state you probably wouldn’t have a sense to help at all.”

“That’s what I’m suggesting,” Yusuf agreed. “I can end up living in a big box from which I already perceive people as objects. When I develop such bigger boxes, I erupt whenever my justifications in the box are challenged or threatened. If I need to be seen as smart, for example, I will get anxious whenever I think my intelligence might be at issue—as, for example, when I am asked to speak in public or when I believe others are evaluating me. If I feel superior, I will be likely to erupt in anger or disdain if others fail to recognize how I am better, or if I perceive that someone is trying to make himself look better than me. And so on. I no longer need to betray my sense regarding another in order to be in the box toward him because I am already in the box. I am always on the lookout for offense when I’m in the box, and I will erupt whenever my justification claims are threatened.”

“So you’re saying that if I find I don’t have many such senses, it may be an indication that I’m already in a box, that I’m carrying my boxes with me, so to speak.”

“I’m suggesting that possibility, yes.”

Lou pondered this.

“I have a different question from Lou’s,” Carol said, raising her hand.

“Sure, go ahead.”

“My problem isn’t that I have too few of these senses to help. I’m worried that I have too many. And frankly, as I think about this, I’m a bit overwhelmed that I have to do everything I feel I should do in order not to betray myself.”

“I have the same question,” Ria said.

Yusuf nodded. “It’s a good thing, then, that that’s not what this means.”

“It’s not?” Carol asked hopefully.

“No. And to see why not, let’s look at the Choice Diagram again. Notice two elements of the diagram: First, notice that we use the words ‘honor’ and ‘betray’ rather than ‘do’ or ‘not do.’ Notice as well the word ‘desire’ along with ‘sense.’ In other words, this sense we’re describing is something akin to a desire. You with me?” he asked Carol before continuing.

“Yes. ‘Honor’ and ‘betray,’ and ‘desire’—I see them.”

“Okay, then, let me ask you this: Have you ever been in a situation where you ultimately weren’t able to do something you felt you should do for somebody, but nevertheless still wished that you could have done it?”

“Sure, all the time,” Carol answered. “That’s exactly what I’m talking about.”

Yusuf nodded in acknowledgment. “Notice how those experiences are different from this experience of mine. In my case, after I failed to help, did I still have a desire to help?”

Carol looked at the diagram. “No.”

“No, I didn’t. You’re exactly right. So notice the difference: in my case, I started with a desire to help but ended with contempt, whereas in your case, you started with a desire to help and ended with a desire to help.”

He paused to let that sink in.

“Although it may be true in such cases that you didn’t perform the outward service you felt would have been ideal, you still retained the sense or desire you had in the beginning. That is, you still desired to be helpful. My guess is that there were probably a number of other things that needed to happen, and you just couldn’t do this additional ideal thing. Am I right?”

Carol nodded.

“And that’s life,” Yusuf shrugged. “We quite commonly have many things that would be ideal to do at any given moment. Whether or not we perform a particular service, the way we can know if we’ve betrayed ourselves is by whether we are still desiring to be helpful.”

“Okay, I think I get it,” Carol said. “So you’re saying that the sense I’m either honoring or not is this desire of helpfulness, not the mere fact of doing or not doing any particular behavior.”

“Yes, Carol, that’s exactly what I’m saying. And that’s why we use ‘honor’ and ‘betray’ on the Choice Diagram rather than ‘do’ or ‘not do.’

“Incidentally,” he continued, “this shows how I can actually behave the way I feel would be ideal but nevertheless still be in the box. Think about the Mordechai story. Let’s say that after I got in the box, I saw someone who knew me, and then out of shame, not wanting to appear insensitive, I turned and helped Mordechai gather his coins, all the while fuming that I was being made to do it. In that case, would I have been seeing him as a person while I was helping?”

“No.”

“Had I retained my desire of helpfulness?”

“No, you hadn’t.”

“So had I honored or betrayed my sense of helpfulness?”

“You’d betrayed it,” Carol said. “Okay, I get it. It’s not simply about the behavior, is it? It’s deeper than that.”

“Exactly. My heart wouldn’t have been at peace even though I was being outwardly helpful, which suggests a betrayal of my original desire to help.”

Carol winced at that comment and bit her lip. “Then that raises another question for me.”

“Go ahead.”

“The situation you described—retaining my desire to help even when I can’t help—explains some of my experiences, but not all of them.”

“Go on,” Yusuf invited.

“Well, a lot of times, when I can’t help, I don’t think I feel peaceful anymore either. To be quite honest, sometimes I’m burning up inside. I feel overwhelmed—all anxious and stressed because I can’t help. It eats me up, and I can’t seem to relax or find peace. Like when my house isn’t clean, for example. I get anxious when we have others over if I haven’t been able to clean up.”

“Ah,” Yusuf responded, “then in those cases it sounds like you might be in the box, doesn’t it?”

Carol nodded.

“And you might, Carol. Ultimately, you’re the only person who would know for sure, but it sounds like you might have developed a hyperactive need-to-be-seen-as box. Maybe you have a box about needing to be seen as helpful, for example, or thoughtful or kind or as a kind of superwoman. Any need-to-be-seen-as boxes like those would likely multiply in your mind the list of obligations you think you have to meet and would likely rob you of peace when you aren’t able to meet them.”

Carol slumped slightly in her chair. “That’s me to a T,” she said. “That’s exactly what I’m like.”

She looked up at Yusuf. “Then where do they come from?”

“Where do what come from?”

“These boxes—like this need-to-be-seen-as box.”

“Again, let’s look at the Choice Diagram,” he said.

Pointing at it, he continued, “When in that story did I have a box—whether of the better-than, I-deserve, worse - than, or need-to-be-seen-as variety?”

“After you betrayed your sense.”

“Exactly. Which is to say that we construct our boxes through a lifetime of choices. Every time we choose to pull away from and blame another, we necessarily feel justified in doing so, and we start to plaster together a box of self-justification, the walls getting thicker and thicker over time.”

“But why have I developed a need-to-be-seen-as box as opposed to some of the others?” Carol followed up.

“Good question, Carol,” Yusuf said. “If you’re like most people, you’ve probably developed boxes that have elements from each of these styles of justification.”

“I think I’m usually in the worse-than or need-to-be-seen-as categories,” Carol said.

“Not me,” Lou interjected, “better-than and I-deserve all the way.”

“What a surprise,” Gwyn joked.

“Yes, shocking,” Elizabeth agreed.

“I wouldn’t want to disappoint you,” Lou said. “You’re expecting it of me now.”

“So why do Lou and I have different kinds of boxes?” Carol asked, returning to the question at hand.

“With respect to the box,” Yusuf responded, “don’t be too taken in by the categories. They are simply linguistic tools that help us think a little more precisely about the issue of justification. The differences they show are in key ways artificial. What I mean is that our similarities are much greater than our differences. What you and Lou share with everyone else on the planet is a need to be justified that has arisen through a lifetime of self-betrayals. If we justify ourselves in different ways, it is because we justify ourselves within a context, and we will reach for the easiest justification we can find. So, for example, if I had been raised in a critical or demanding environment, it might have been easier for me, relatively speaking, to find refuge in worse-than or need-to-be-seen-as justifications. Those who were raised in affluent or sanctimonious environments, on the other hand, may naturally gravitate to better-than and I-deserve justifications, and so on. Need-to-be-seen-as boxes might easily arise in such circumstances as well.

“But the key point, and the point that is the same for all of us, is that we all grab for justification, however we can get it. Because grabbing for justification is something we do, we can undo it. Whether we find justification in how we are worse or in how we are better, we can each find our way to a place where we have no need for justification at all. We can find our way to peace—deep, lasting, authentic peace—even when war is breaking out around us.”

“How?” Carol asked.

“As Avi said a few minutes ago, that is our topic for tomorrow.

“For tonight, we invite you to ponder what boxes you are carrying, and the nature of your predominant self-justifications.

“I also invite you to consider how your box—this warring heart that you carry within—has invited outward war between you and those in your life.

“Remember this Collusion Diagram?” he asked, pointing at the picture of Avi and Hannah’s conflict about the edging.

Most of the group nodded.

“Look for that pattern in your own lives tonight,” he said. “See where you might be inviting in others the very behavior you are complaining about. Ponder what boxes might be behind your reactions in those situations. Try to figure out what self-justifications you are defending.”

Yusuf looked around at the group. “In short, our invitation to you for tonight,” he said, “is to notice your battles and to ponder your wars. Using the conflict in the Middle East metaphorically, we are, all of us, Palestinian and Israeli in some areas of our lives. It will serve neither ourselves nor our loved ones to think that we are better.

“Have a good evening.”