Chapters 12 and 13 introduce the four common styles of justification: better-than, worse-than, I-deserve, and need-to-be-seen-as. Many readers have told us how helpful it has been to understand these different kinds of boxes—especially to learn about the worse-than style of justification, as we didn’t explore that kind of box in our first book, Leadership and Self-Deception. Since two of the characters in The Anatomy of Peace, Carol and Avi, tend toward the worse-than style and also toward its common companion, the need-to-be-seen-as box, we were able to explore these kinds of boxes in more depth in this book.

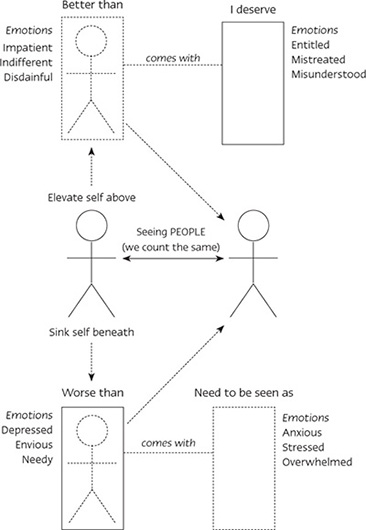

The book discusses how better-than and I-deserve boxes, and worse-than and need-to-be-seen-as boxes, often come together. After the publication of the first edition, we developed the Carry-Box Diagram to help people see how these different box styles interrelate. We call these various styles of justification carry boxes because they are box styles that we acquire and carry with us over a lifetime of betraying ourselves. Most people have acquired versions of each of these styles of justification, although one or two styles may be more common for them.

In our workshops, we always introduce these boxes through the Carry-Box Diagram. We considered including the diagram in the body of this new edition of the book but finally decided to keep the flow of the original story through that section and to include this diagram and some further explanation here.

THE CARRY-BOX DIAGRAM

When teaching people about this diagram, we build it element by element, beginning with the two figures in the center. The person on the center left represents each of us. The person on the center right represents people we are out of the box toward. When we are out of the box, we regard others as mattering like we matter. We capture this idea in the diagram by placing both of these figures on the same level; each of us counts like the other.

This means that when we go into the box, we move away from this core truth that others matter like we matter. We can move away from this core truth in two different ways. In the first of these ways, we go into the box by elevating ourselves above others. When we do this, others no longer count like we count. We feel superior and look down on them. This is the stance that we call the better-than box.

When we feel that we are better than others, we very naturally feel like we deserve things that others don’t—more praise, for example, or an apology, a bigger paycheck, a nicer house, more free time, and so on. This is why we connect the I-deserve box to the better-than box in the diagram.

The other way we can move away from the core truth that others count like we count is to sink ourselves beneath others. Instead of counting the same, we now feel that we count less than others. We see others as being way up on a pedestal as compared to ourselves. We call this stance the worse-than box. From within the worse-than box, we feel justified for our separation from others on the grounds that we aren’t smart enough, funny enough, successful enough, and so on.

The worse-than box has its own companion box. When we feel that we are worse than others, we can find ourselves in situations where it is very important to us not to be seen as worse than others. For example, let’s suppose that a person in the workplace has a worse-than box around his or her intelligence. Since in a corporate setting there is likely little benefit gained from being seen as less intelligent than others, someone with such a worse-than box is likely to take on another box around wanting to be seen as not being less intelligent. We call this kind of box a need-to-be-seen-as box. One can have this kind of box around almost anything—needing to be seen as smart, funny, popular, attractive, hardworking, one who never makes mistakes, and so on.

We can recognize what kind of boxes we might be in by paying attention to the emotions we are experiencing, as certain kinds of emotions often correspond to specific boxes. In the diagram, we list a few emotions for each box style that can very often be indicative of that particular style.

We see these various box styles at play in the characters in the story. When Lou is in the box, he most often defaults to a better-than or I-deserve style. Carol, on the other hand, more often goes into the worse-than or need-to-be-seen-as box.

You might think about what box styles are most common for you—at home, at work, and in the community.