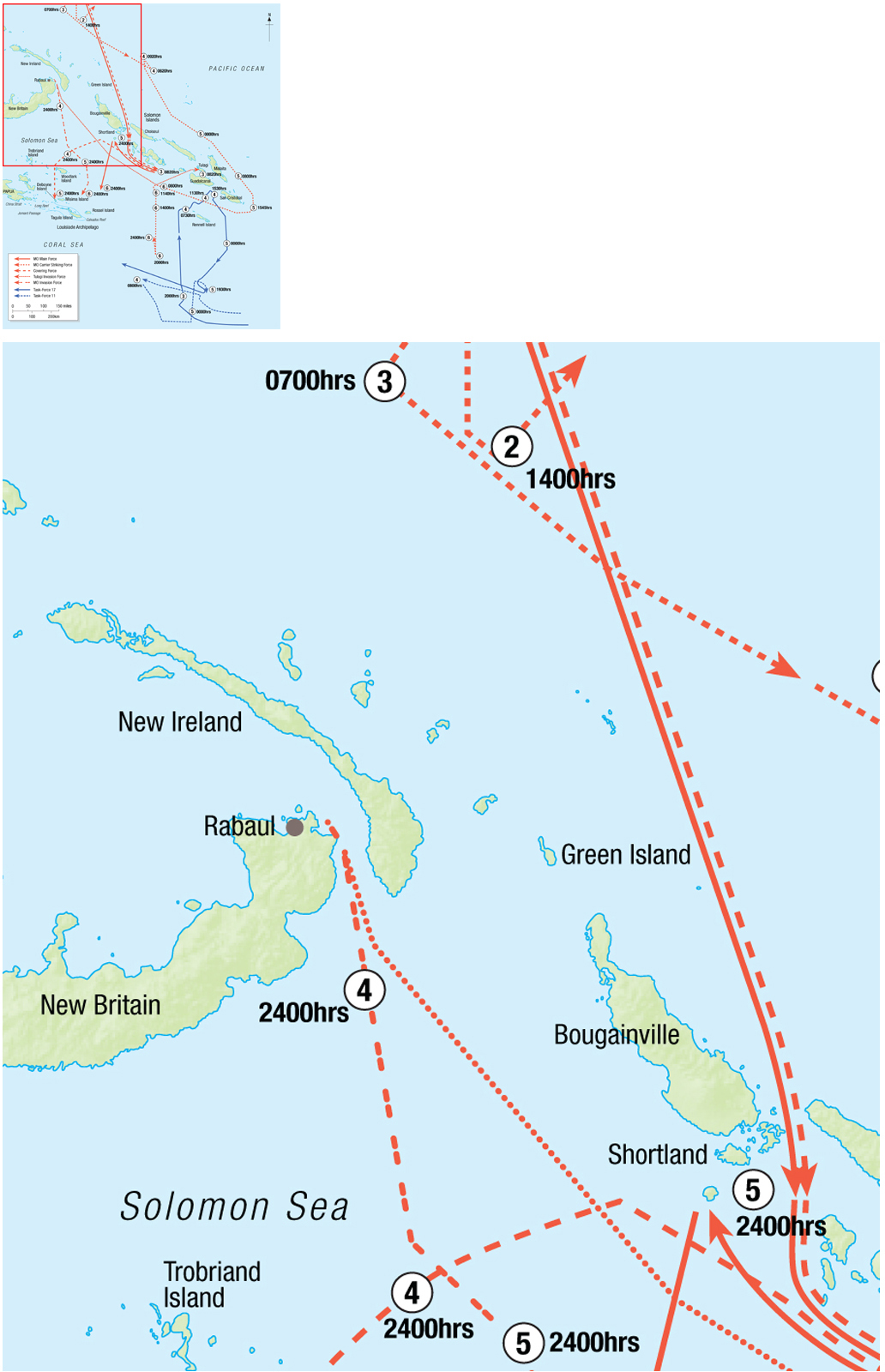

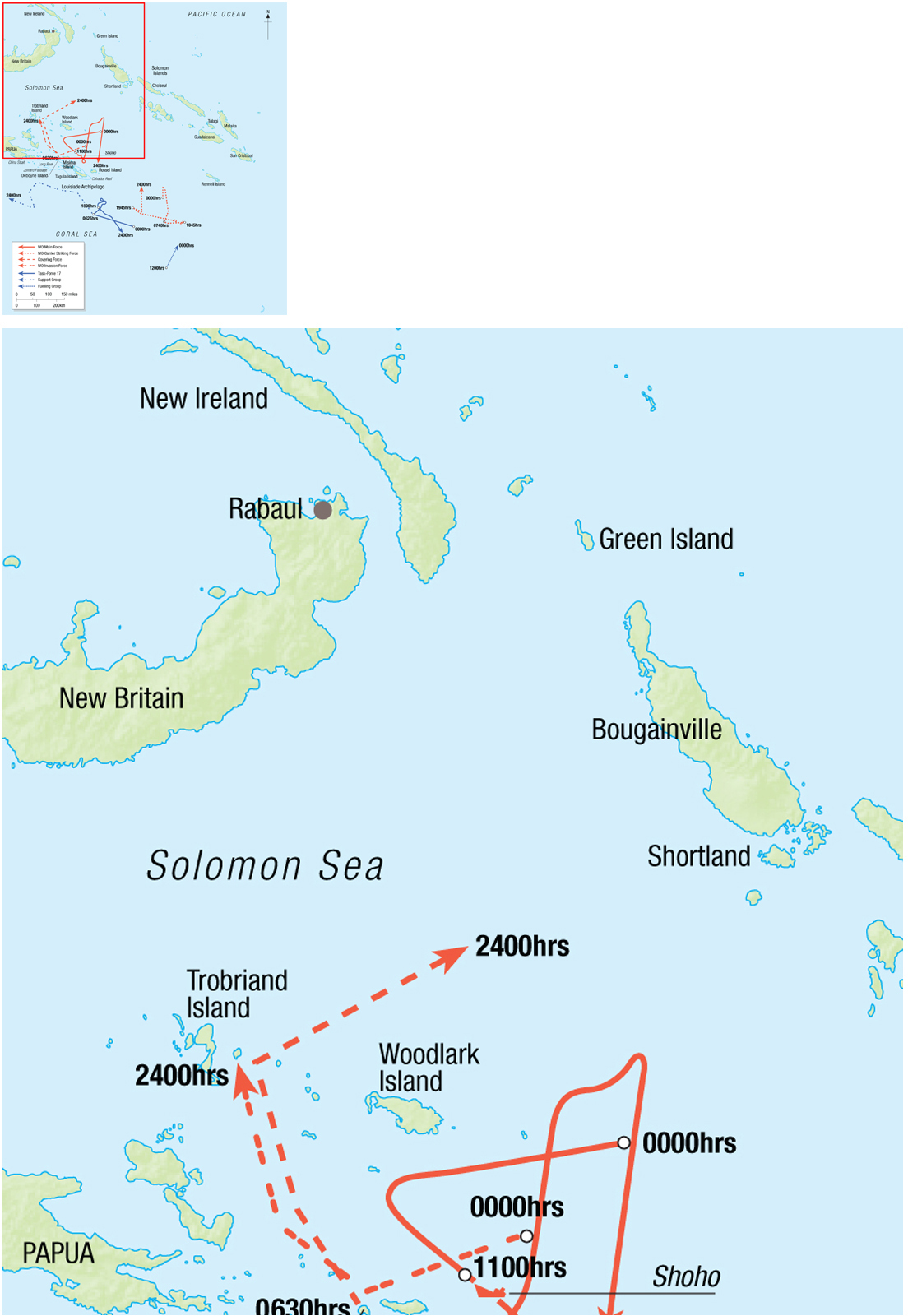

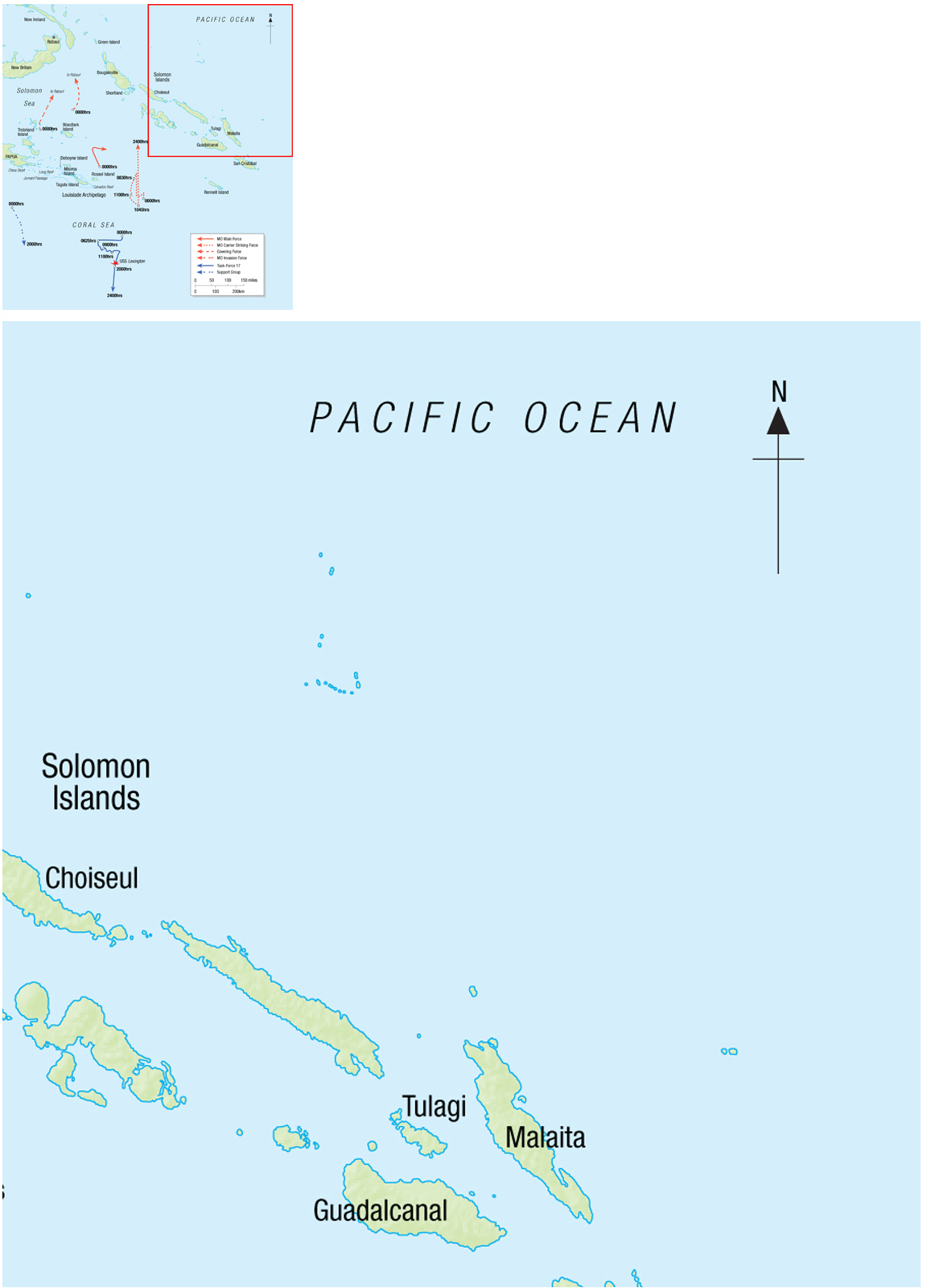

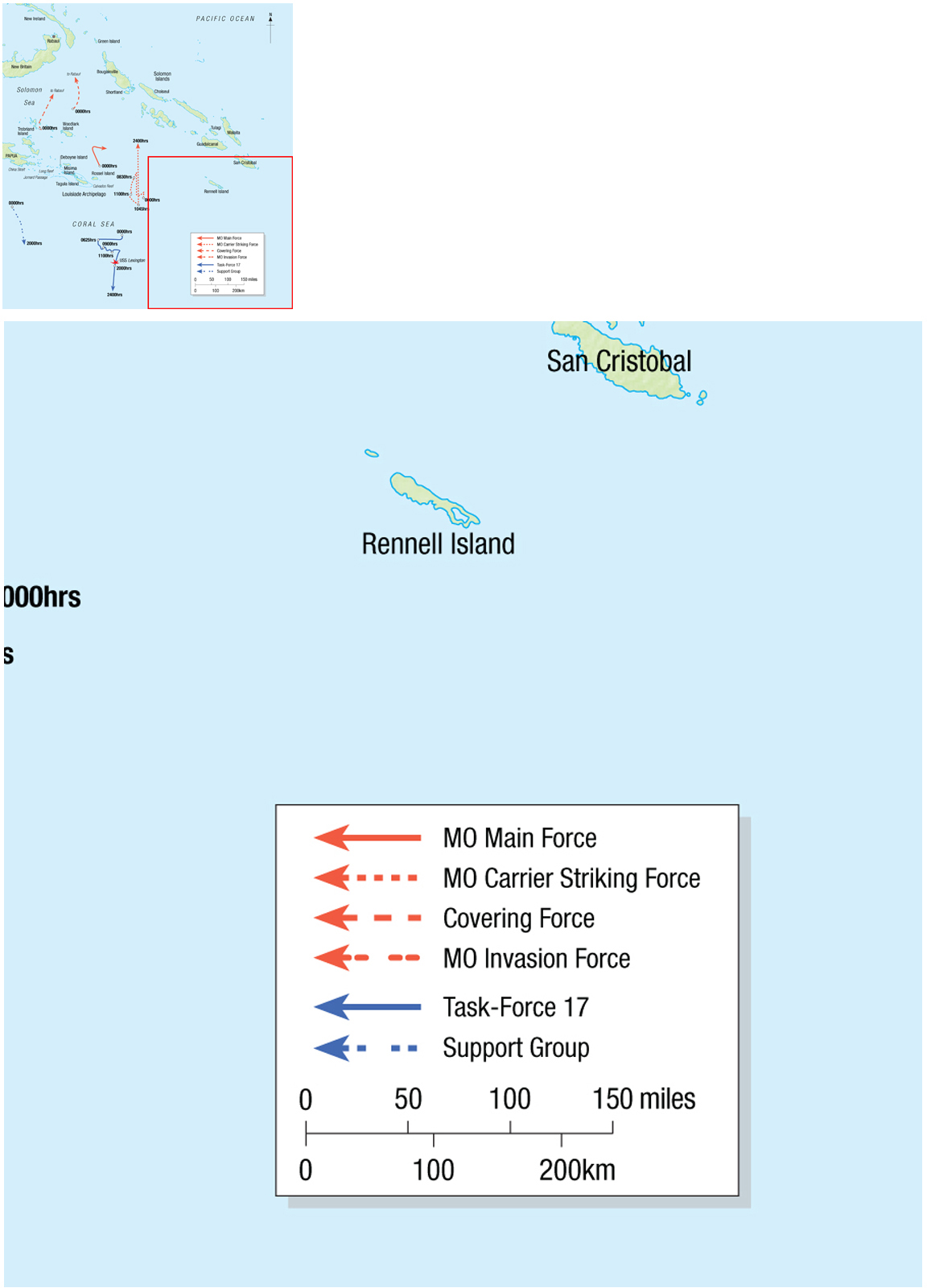

By the end of April, events in the South Pacific began to gain momentum. On April 28, the Japanese improvised a seaplane base at Shortland Island in the Solomons and moved five long-range H6K4 Type 97 flying boats (codenamed “Mavis” by the Allies) to the facility. These aircraft possessed a remarkable normal range of almost 3,000 miles and provided the Japanese commanders scouting coverage well into the Coral Sea. The next day, the Tulagi Invasion Force departed Rabaul and the Main Body (including Shoho) departed Truk. On May 1, the MO Carrier Striking Force left Truk.

The first blow of the battle was delivered on the morning of May 3 when the 3rd Kure Special Naval Landing Force landed unopposed on the islands of Tulagi and Gavutu. This move was supported by aircraft from Rabaul and the carrier Shoho, which had moved to a position 180 miles west of Tulagi to cover the landings.

Thus far, everything seemed to be running according to plan for the Japanese. However, by the end of May 3, the tightly synchronized MO plan was already running into trouble. The Carrier Striking Force was tasked with the seemingly simple mission of ferrying nine Zero fighters from Truk to Rabaul. This was to occur on May 2 when the carriers would be closest to Rabaul on their way south. However, when the nine fighters took off on schedule for Vunakanau Airfield on New Britain, they were forced to return to the carriers because of bad weather. An attempt to repeat the operation the following day was also thwarted by weather with one of the planes being lost in the attempt. The carriers were now two days behind schedule, yet the Japanese never considered delaying the remainder of the operation. The Japanese viewed the delivery of the fighters with such importance because of the requirement to reinforce Rabaul’s air strength, which was key to gaining air superiority over Port Moresby. This episode shows how little allowance was made in Japanese planning for even the smallest things to go wrong, as well as the basic weakness of a plan that hinged on a factor as small as nine fighters in the first place.

The destroyer Yugure was one of four Hatsuharu-class destroyers in Destroyer Division 27 assigned to the MO Carrier Striking Force. Completed in 1935, Yugure carried six 24in. torpedo tubes and five 5in. guns, but only two triple 25mm mounts for protection against air attack. (Yamato Museum)

The New Orleans-class heavy cruiser Astoria was part of TF-17’s screen during the battle of the Coral Sea. She served in the same capacity at Midway before being sunk by Japanese heavy cruisers at the battle of Savo Island in August 1942. (US Naval Historical Center)

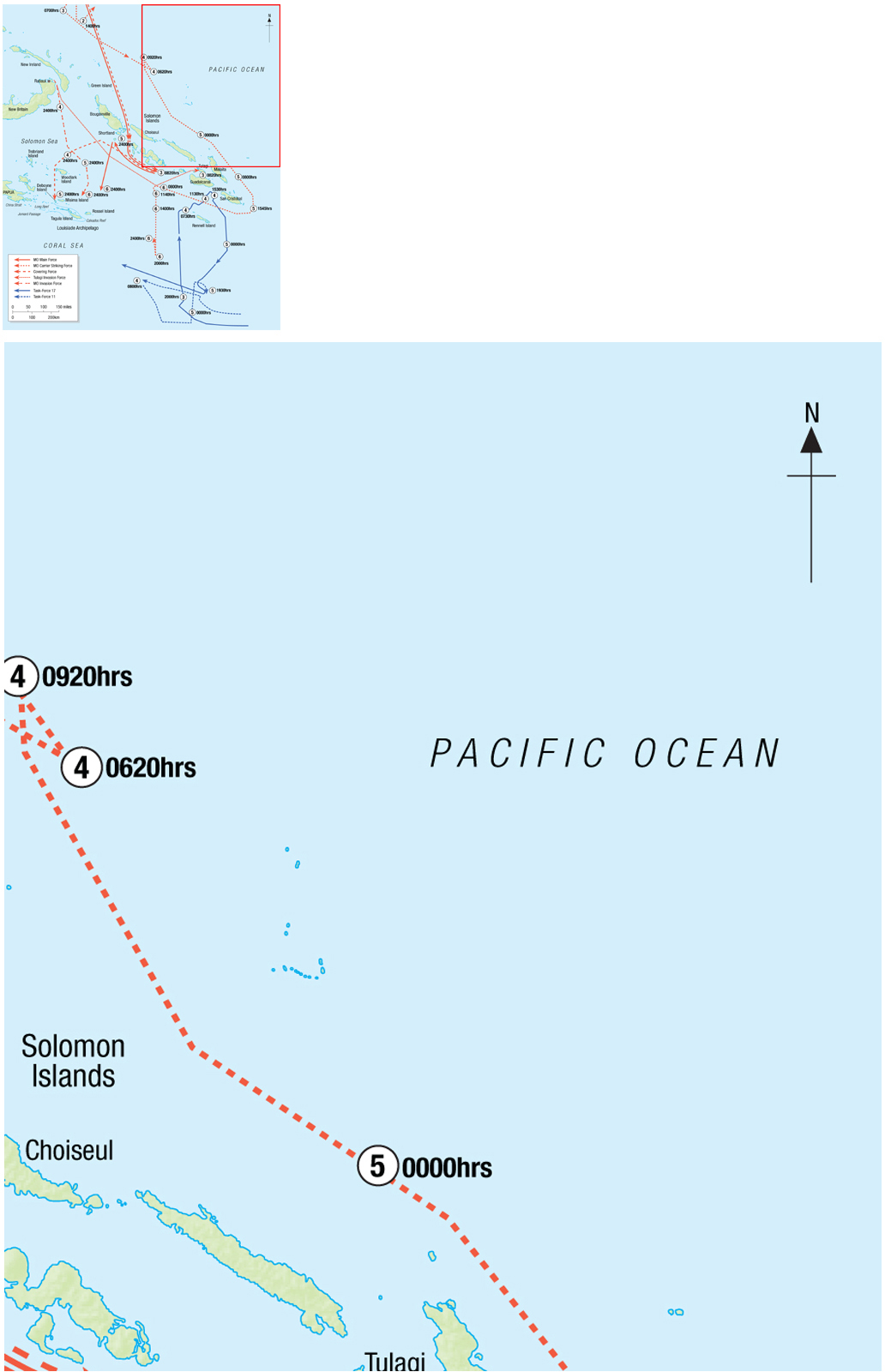

As the Japanese carriers attempted to complete their ferry mission, Fletcher was just getting reports of the occupation of Tulagi around 1900hrs on the evening of May 3. His forces were already at sea, waiting for word of any Japanese advance. Despite the fact that MacArthur’s air force had provided no advance warning of the Tulagi invasion, here was information Fletcher could act on. Early on May 3, TF-17 was slowly moving westward into the central Coral Sea. Fletcher and TF-17 had become separated from Lexington as TF-11 completed its refueling. Actually, Lexington had completed refueling early and was close to Fletcher’s position. Strict radio silence denied Fletcher this knowledge, so when reports came in of the invasion of Tulagi, he decided to react immediately with TF-17 alone. Fletcher turned his force north by 2030hrs and worked up to 27 knots to be in a position to attack Japanese forces off Tulagi at dawn on May 4. He was aware that this would reveal the presence of a US carrier in the area, but Fletcher was more concerned with surprising the Japanese and delivering some punishing blows.

By May 4, the Tulagi Invasion Force was without air cover. Shoho had departed to move north to cover the Port Moresby invasion convoy then departing Rabaul and the MO Carrier Striking Force was still in the area of Rabaul attempting to complete its frustratingly difficult ferry mission. When American carrier aircraft appeared over the skies of Tulagi on the morning of May 4, the Japanese were caught completely by surprise and were essentially defenseless.

Northampton-class heavy cruiser Chester in August 1942. Chester was active early in the war as a carrier escort, including at the battle of the Coral Sea. Her port side 5in. gun battery can be seen pointed skyward. Armed with a total of eight 5in. guns, four 1.1in. quadruple automatic cannon mounts and a variable number of 20mm guns, the Northampton-class cruisers possessed an impressive anti-aircraft fit by early 1942 standards. (US Naval Historical Center)

At 0630hrs, Yorktown began launching what would be the first of four strikes. The first wave included 28 dive-bombers and 12 torpedo bombers. No fighter escort was provided as no air opposition was expected. The attack began at 0820hrs. Large targets were few with the large minelayer Okinoshima and two destroyers being the most valuable. The most notable result of the first strike was the damaging of destroyer Kikuzuki, which was later beached and lost. The same aircraft were turned around for a second strike with 27 dive-bombers and 11 torpedo bombers attacking again just after noon. Later, a third wave was sent in with 21 dive-bombers, departing Yorktown at 1400hrs and returning at 1630hrs. The results of this intense effort, and of a wave of four fighters launched to strafe the Type 97 flying boats located in Tulagi harbor, was very disappointing. Fletcher claimed that two destroyers, one freighter and four patrol craft had been sunk and a light cruiser driven aground. The real tally was much less. In addition to the destroyer Kikuzuki, three small minesweepers and four landing barges had been sunk. Perhaps the most important result was the destruction of the five Type 97 flying boats. Total Japanese casualties were 87 killed and 124 wounded.

The Mutsuki-class destroyer Kikuzuki, shown here beached in December 1944, was the largest Japanese ship sunk in Yorktown’s May 4 raid on Tulagi. Casualties among the ship’s crew included 12 killed and 22 wounded. (US Naval Historical Center)

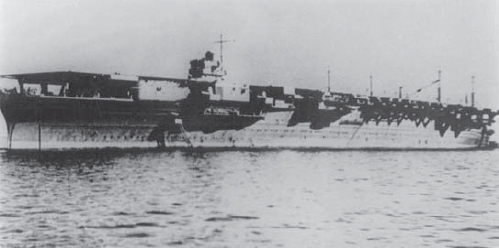

Zuikaku was completed in September 1941, as shown here, just in time to join the Kido Butai for the Pearl Harbor operation. She was the last of the six Peal Harbor carriers to be sunk, lasting until the battle of Leyte Gulf in October 1944. (US Naval Historical Center)

Following his strike against Tulagi, Fletcher headed south at high speed. The Japanese had no idea where the carrier was that mounted the raid, so Fletcher was easily able to escape retaliation. On the morning of May 5, he rendezvoused with TF-11 approximately 325 miles south of Guadalcanal. He now took his combined force to the southeast using the opportunity to refuel TF-17. Around 1100hrs, a Wildcat from Yorktown destroyed a Type 97 flying boat from Shortland. The Japanese aircraft did not have time to send a signal, but its destruction gave them a vague notion of the location of an American carrier.

Meanwhile, the Japanese carrier force was groping in the dark. The American raid on Tulagi found the Japanese carriers fueling north of the Solomons. In response to reports of the American attack, Takagi rushed his force to the southeast expecting to find an American carrier east of Tulagi. After finding nothing, Takagi confirmed his intention of entering the Coral Sea from an area east of the Solomons. On the evening of May 5, Takagi turned to the west after rounding San Cristobal Island in the southern Solomons. He planned to fuel on May 6 some 180 miles west of Tulagi before turning south into the Coral Sea. Thus throughout the day on May 5, neither carrier force had any real idea where the other was.

Fletcher was receiving extensive reporting from MacArthur’s air units on the location and movement of a number of Japanese units active in the Solomon Sea. This included reports of carriers. On May 4 at around noon, an American bomber reported a force, with a carrier, off Bougainville. This was eventually reported to Fletcher as a Kaga-class carrier. On May 5, another report was issued of a Japanese carrier operating southwest of Bougainville. What MacArthur’s airmen had sighted was the Shoho headed north to cover the MO Invasion Force, which had departed Rabaul on May 4.

Kikuzuki was one of two Mutsuki-class destroyers assigned to the Tulagi Invasion Force. The Mutsuki class was the first class of Japanese destroyer to carry the deadly 24in. torpedoes. As was the case with most early war Japanese destroyers, she carried a negligible anti-aircraft armament. (Yamato Museum)

The light carrier Shoho was attacked on the morning of May 7 by a total of 93 aircraft from two American carriers. Within 15 minutes, the carrier was ripped apart by some 13 bombs and at least seven torpedo hits. Shoho quickly sank with heavy loss of life. (US Naval Historical Center)

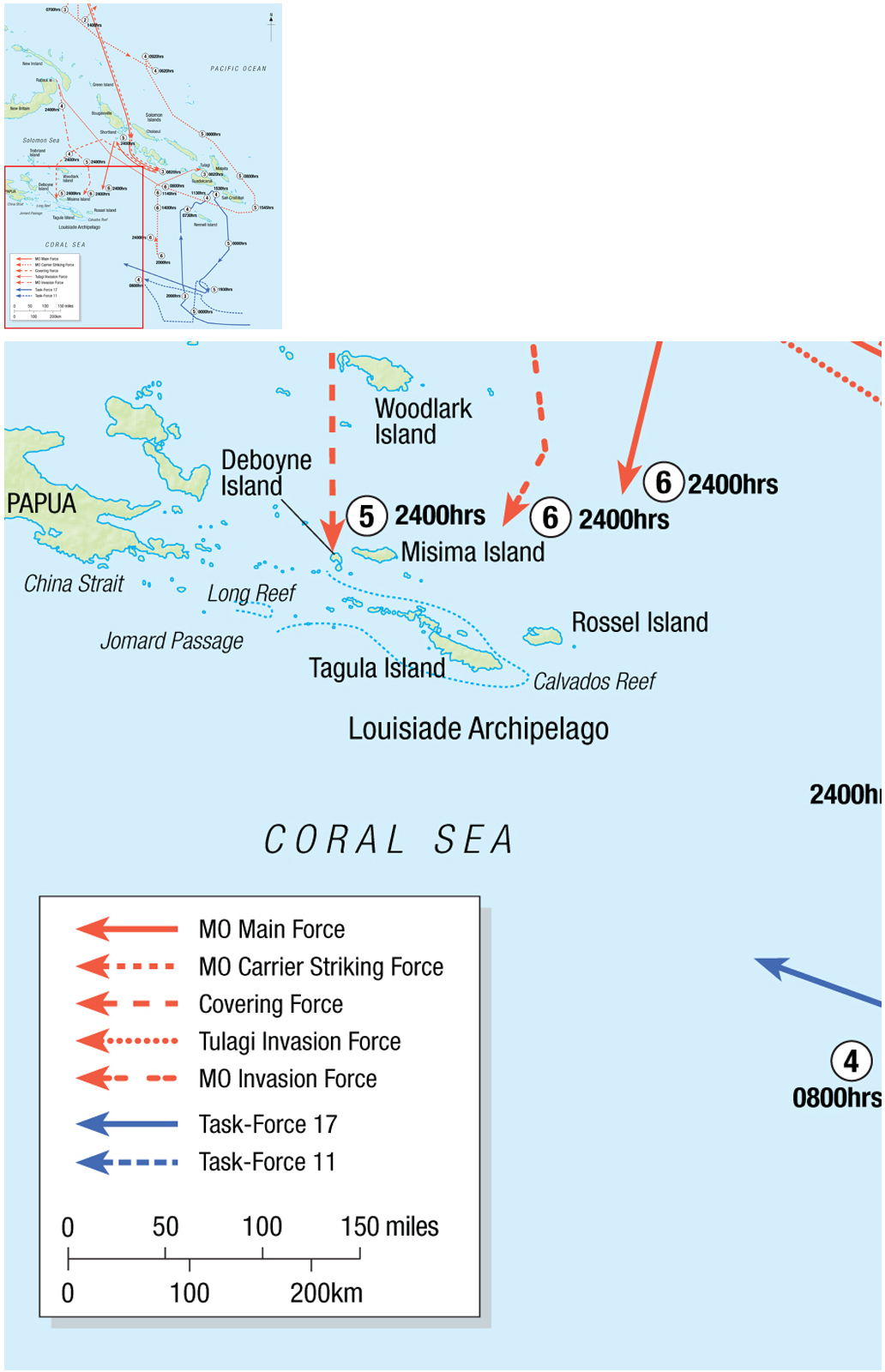

On May 6, Fletcher exercised his authority from Nimitz to merge all three task forces into TF-17. His total strength was two carriers, eight cruisers (two Australian) and 11 destroyers. Fletcher ordered his combined force to head southeast throughout the day to refuel in deteriorating weather. No contact was made by TF-17’s scouting dive-bombers, though one Dauntless ended its planned track a mere 20 miles from the Japanese carriers operating south of New Georgia. Just after noon, MacArthur’s airmen reported a carrier and four other warships southwest of Bougainville. Fletcher’s afternoon scout missions flying 275 miles north and northwest of TF-17 located nothing. With the Allied Air Forces’ reconnaissance efforts still focused on the Solomon Sea and the Louisiades, Fletcher remained ignorant of the true location of the Japanese carrier force, now located to his northeast.

At 1015hrs on May 6, radar revealed the presence of a snooper in the area of TF-17 that fighters on CAP were unable to locate. Fletcher now had to assume that his position was compromised. With no intelligence generated by his own scouts, Fletcher had to assume that the numerous contact reports from Allied Air Forces aircraft confirmed the signals intelligence he had been receiving from Nimitz which indicated that Japanese carriers were tasked to strike Port Moresby on May 7 and that the Japanese invasion convoy would transit the Louisiades at the Jomard Passage on May 7 or 8. However, the Americans had yet actually to sight the invasion convoy, and of course, Fletcher remained ignorant of the actual location of the Japanese carriers. On the evening of May 6, Fletcher brought TF-17 to the northwest and increased speed to 21 knots. He aimed to be 170 miles southeast of Deboyne Island on the morning of May 7 to strike the Japanese forces reported off Misima Island in the central Louisiades.

The Japanese were the first to get solid information on the location of the enemy carriers. At 1030hrs, the aircraft spotted by TF-17 radar (actually a Type 97 flying boat) reported TF-17 420 miles southwest of Tulagi. However, the aircraft provided an incorrect position (off by 50 miles) and an incorrect course and speed. The report, received by Takagi at 1050hrs, caught the Japanese carriers in the middle of fueling. The American carriers were reportedly 350 miles south (actually 300 miles). Not until 1200hrs were the two carriers, escorted by two destroyers, released to head south to chase the contact. Hara decided not to launch a long-range strike or mount his own air search not wanting to reveal his presence to the Americans. He continued to head south until 1930hrs on May 6, coming to within 60–70 miles of TF-17.

May 6 was a day of missed opportunities for both sides. While US carrier planes had just missed spotting their main opponents in the morning, Hara continued to play a passive game of ambush and failed to follow up aggressively on the solid lead given him by Japanese long-range search planes. Even after this lead went cold at least Hara had a general idea of the location of the American carriers. On the other hand, Fletcher continued to believe that the Japanese carriers were operating to his northwest. With both forces continuing to close, a clash on May 7 was all but certain, and there was a grave potential that the Japanese carriers could unleash a deadly ambush on their unsuspecting opponents.

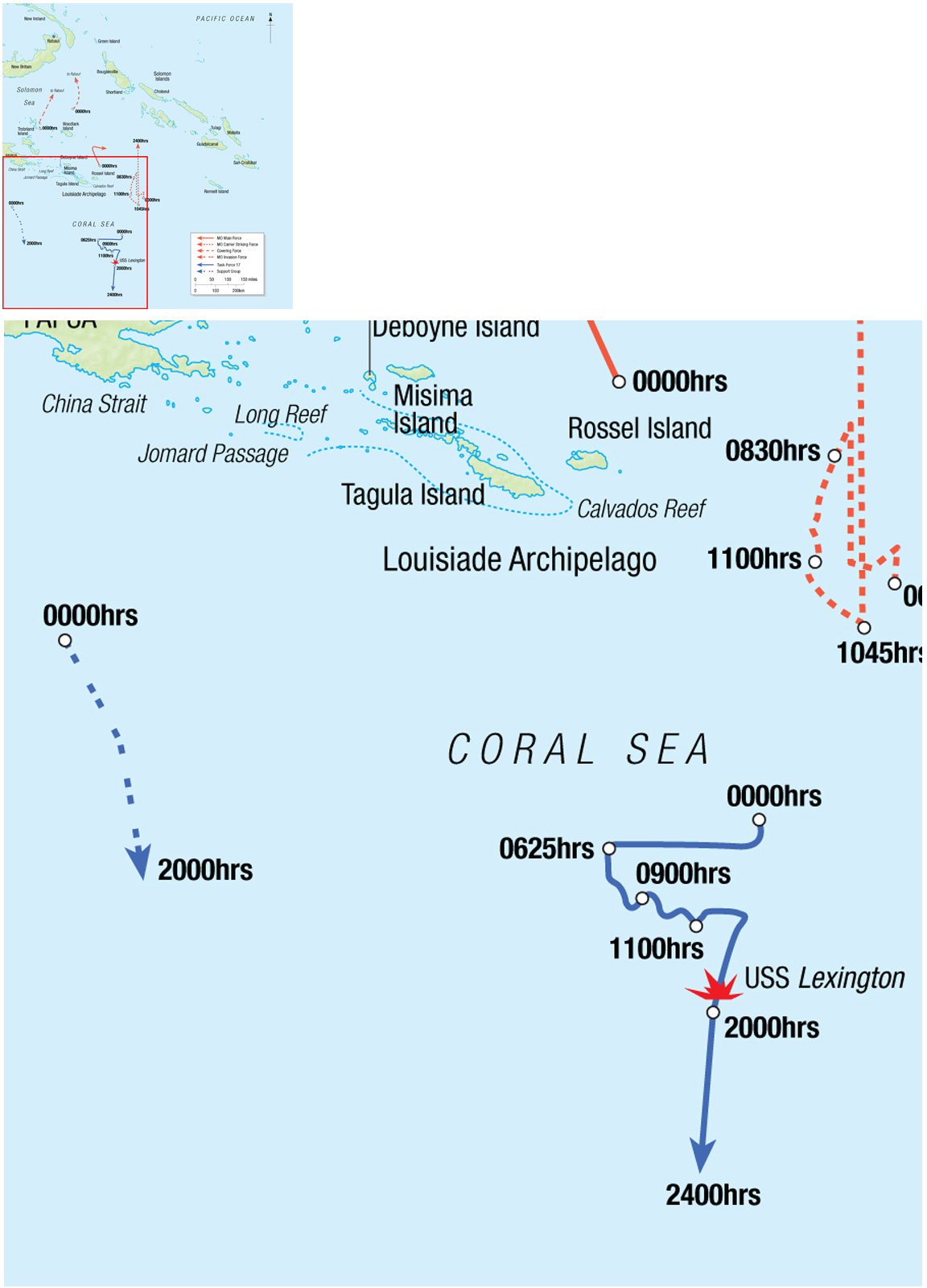

On the morning of May 7, TF-17 was positioned approximately 150 miles south of Rossel Island. This placed it between the two main Japanese forces. The MO Invasion Force was located north of the Jomard Passage with Goto’s Main Force located northwest of the convoy. The MO Carrier Striking Force was operating approximately 300 miles southwest of Tulagi, which placed it approximately 200 miles southeast of Fletcher. Fletcher was focused on striking the Japanese force operating in the Solomon Sea including the Japanese carriers he assumed were located somewhere south of Bougainville. He still had no idea of the true location of the main Japanese carrier force. The Japanese also found themselves in a not entirely favorable position. While they still hoped to stage an ambush on the unsuspecting American carriers, they had yet to adjust the MO plan to the fact that the Carrier Striking Force was behind schedule and that an American carrier force was now blocking the advance of the Invasion Force and was closer to the transport force than were the Japanese carriers. Inoue had yet to adjust the movement of the invasion convoy and its continued advance southward now made it vulnerable to American air strikes. While Fletcher had the option of waiting and reacting to Japanese moves, the Japanese would have to force a decision quickly if the operation was to stay on schedule.

A Douglas Devastator from USS Enterprise over Wake Island on February 24, 1942. The highlight of the Devastator’s early war career was at the Coral Sea when the aircraft put several torpedoes into the Japanese light carrier Shoho. A month later at the battle of Midway, the aircraft’s true vulnerability was revealed. (US Naval Historical Center)

A fine view of the heavy cruiser Furutaka in 1939 following modernization. Furutaka and her sister ship Kako both survived the Coral Sea but were both lost during the fierce battles around Guadalcanal later in 1942. (Yamato Museum)

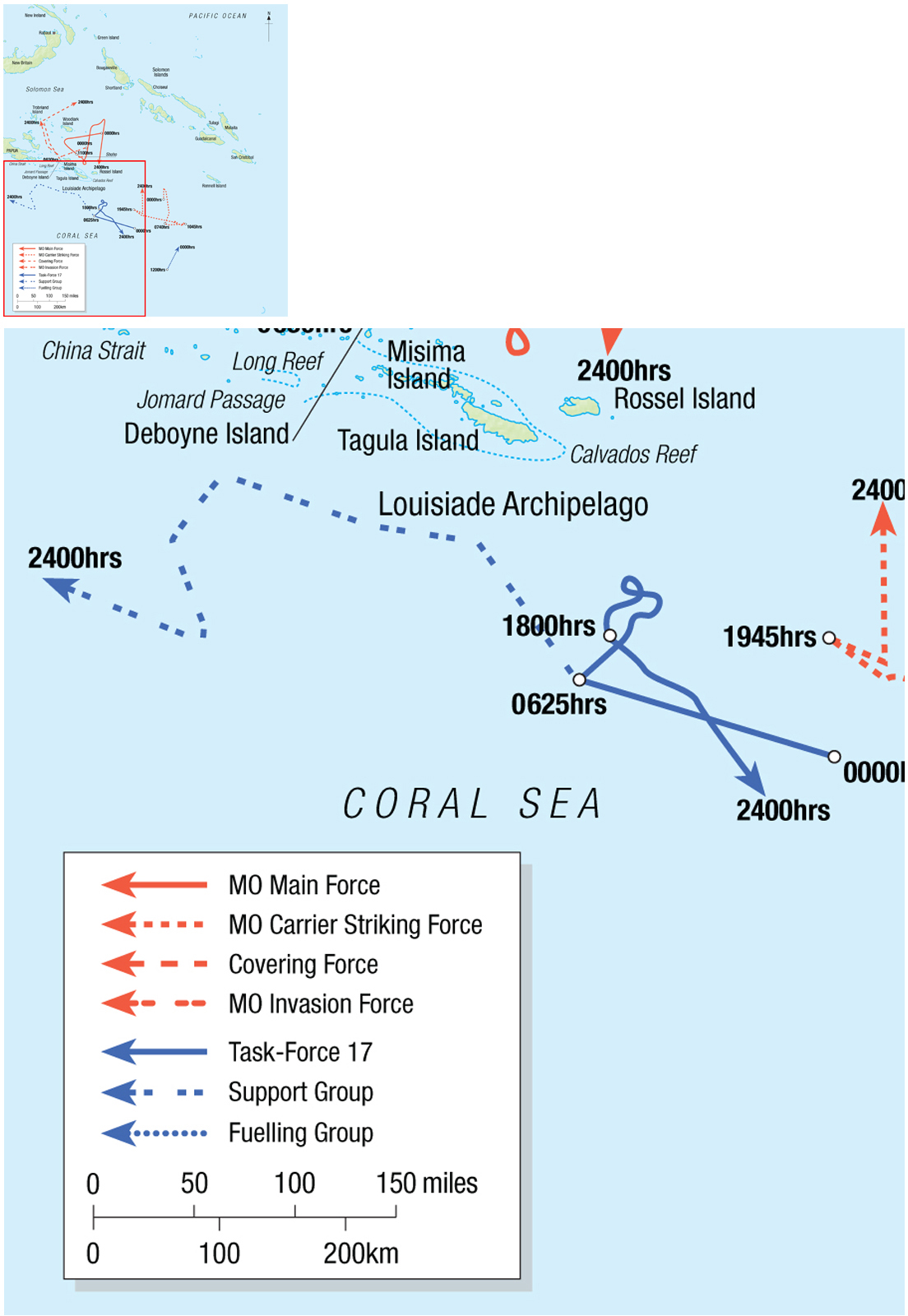

For both sides, the key to success was reconnaissance. On May 7, both commanders were severely let down by the efforts of their reconnaissance aircraft and crews and these series of mistakes would shape the battle. Allied Air Forces’ aircraft continued to focus their efforts on the area north of the Louisiades and into the Solomon Sea. Fletcher augmented this with the dispatch of 10 Dauntlesses from Yorktown at 0600hrs. These were assigned sectors from the northwest through the east out to 250 miles. The Japanese also made a large-scale scouting effort. Aircraft from Rabaul, the Shortlands, Tulagi and the newly created seaplane base on Deboyne Island would search south of the Louisiades. Meanwhile, no longer trusting in the efficiency of land-based searches alone, Hara decided to use 12 B5N carrier attack aircraft to search from 160 to 270 degrees out to a distance of 250 miles from his force. The first side to receive solid contact reports would probably be the first to launch its strike, thus grabbing victory.

Also at dawn on May 7, Fletcher decided to detach TG-17.3 under the command of British Rear Admiral J. G. Crace. Under his command Crace had his three cruisers, and with the addition of another American destroyer, a total of three destroyers. Crace’s mission was to prevent the MO Invasion Force from passing south of the Louisiades. This was a controversial move as it removed one third of Fletcher’s already weak carrier screen and placed a force with no air cover within range of Japanese land-based aircraft. It was also debatable that the force could accomplish its mission at all. If the carrier battle went badly for the Americans, the Japanese would have little difficulty sweeping aside Crace’s force. On the other hand, if the carrier battle went well for the Americans, the Japanese would have to suspend the invasion anyway. Fletcher’s rationale was that if the carrier battle neutralized both forces, as often happened in US Navy prewar exercises, then Crace would be positioned to contest the Japanese advance into the Coral Sea. Under the circumstances, this seemed a good insurance move by Fletcher, especially given that the anti-aircraft contribution by Crace’s ships to the defense of TF-17’s carriers was minimal.

The Royal Australian Navy (RAN) heavy cruiser Australia was the flagship of Rear Admiral Crace during the battle. Australia was a County-class Treaty cruiser completed in 1928 for the RAN by the British. Her main armament consisted of eight 8in. guns. This view was taken in August 1942. (US Naval Historical Center)

Given the relatively small area of operations and the numbers of ships and aircraft in motion, contact reports quickly filtered up to the respective commanders. Hara was the first to receive a solid contact report and his subsequent actions will be dealt with first. His 12 scout aircraft had departed at 0600hrs and were focused on the area south and southwest of his position. What Hara did not know was that Fletcher was closer to his force than he thought (just over 200 miles), and that he had moved north and the Japanese carrier-borne search effort was off the mark. This mattered little to Hara when at 0722hrs, two Type 97 carrier attack planes from Shokaku reported an American force of one carrier, one cruiser and three destroyers only 163 miles south of the Japanese carriers. Later, an oiler and a cruiser was reported some 25 miles southeast of the carrier. This was the information that the Japanese had been waiting days for and it fitted perfectly with Hara’s estimate of where the Americans should be. Hara sent another carrier attack plane to confirm the report and made preparations to launch a full strike. By 0815hrs, a total of 78 aircraft (18 fighters, 24 torpedo bombers and 26 dive-bombers) were on their way to destroy the carrier under the command of Lieutenant-Commander Takahashi Kakuichi.

What appeared to be a promising situation for the Japanese quickly turned into a potential disaster. Upon arriving at the reported contact just after 0900hrs, Takahashi found only the oiler and its escort. An enlarged search of the area found nothing. Things got worse when Hara received reports from a floatplane from the cruiser Kinugasa (part of the MO Main Force) searching south of the Louisiades that it had spotted American carriers southeast of Rossel Island. The force consisted of a Saratoga-class carrier and a second carrier, and at 1008hrs they were in the process of launching a strike. At 1051hrs, the original searchers from Shokaku returned and revealed that they had only seen an oiler. Faced with this alarming turn of events, Hara recalled his strike at 1100hrs.

The Mitsubishi A5M Type 96 carrier fighter was the IJN’s standard shipborne fighter until the advent of the A6M Type 0 fighter. Four of these obsolescent aircraft were assigned to the Shoho Air Group for the MO Operation. (Ships of the World Magazine)

USS Sims in May 1940. Completed in 1938, she was the lead ship of her class, which was often used for carrier-screening duties early in the war. Main armament was five 5in. guns and 12 21in. torpedo tubes. During the battle, she was caught alone and quickly overwhelmed by Japanese dive-bombers. (US Naval Historical Center)

Before leaving the area Takahashi unleashed his dive-bombers on the only targets in view. The first four Type 99 carrier bombers selected the destroyer Sims as their target and quickly destroyed her with three hits by 550-pound bombs. The destroyer sank by the stern suffering heavy loss of life. The oiler Neosho was the target of over 30 dive-bombers, which straddled her 15 times and gained seven hits. One carrier bomber was shot down during the 18-minute attack. The ship was left listing, aflame and without power. However, half the crew re-boarded the ship and put out the fires and was later saved by an American destroyer after the battle. The tanker was finally scuttled and the remaining crew rescued on May 11.

USS Neosho refueling Yorktown on May 1. Neosho was bombed by Japanese carrier aircraft on May 7 and was finally scuttled on May 11. Throughout the battle, Fletcher devoted considerable attention to maintaining proper fuel levels for his forces. (US Naval Historical Center)

The Japanese had squandered an opportunity to ambush the Americans and had sunk only two minor ships in return. The last of the strike had not returned until after 1500hrs, so the prospects of launching another strike that day on the real American carriers looked doubtful. Fortunately for Hara, the strike on the oiler group did not fatally compromise his position. Later in the day, Fletcher was aware that Neosho had been attacked, but neither ship had radioed a distress signal before it was sunk or put out of action. Sims had sent an aircraft contact report, but it was not picked up by TF-17. The only word from Neosho was at 1021hrs that she was under attack by three aircraft. Since this could have been from long-range aircraft from Tulagi, Fletcher and his staff were still unaware that a large carrier-based strike had destroyed his supporting oiler.

As the Japanese struggled to clarify their situation, an almost identical situation developed for the Americans. However, in their case, circumstances developed more favorably. As early as 0735hrs, Fletcher received word from his scouts of Japanese activity. The first sighting was of two cruisers northwest of Rossel Island. This report was followed by a contact at 0815hrs of two carriers and four cruisers north of Misima Island. The location of the force was 225 miles northwest of TF-17, which put it beyond the range of the fighters and torpedo planes. However, with the Japanese force reported moving south and Fletcher moving north, a full attack was judged to be possible. Fletcher waited over an hour to launch, but beginning at 0926hrs, Lexington began to put her strike of ten fighters, 28 dive-bombers and 12 torpedo bombers into the air. At 0944hrs, Yorktown began the first of two launches, committing eight fighters, 25 dive-bombers and ten torpedo bombers to the attack.

However, as soon as the planes were headed north, things began to go wrong. Throughout the morning, radar had reported air contacts in the vicinity of the task force. Though fighters were unable to locate the snoopers, Fletcher assumed, correctly, that he had been located. Added to this, was the report from Neosho at 1021hrs that she was under attack. Worse still, the return of the scout plane that had reported the two carriers revealed that the actual report had meant to report the spotting of four light cruisers and two destroyers. Confronted with the same dilemma that Hara had faced, Fletcher declined to recall his strike. He knew from Allied Air Forces’ reporting that there was heavy Japanese activity in the planned strike area. The situation brightened when Fletcher received a report at 1022hrs from Port Moresby that two hours earlier a B-17 had reported a large force including a carrier, ten transports and 16 other ships just south of the false carrier report. Fletcher passed this new information to the airborne strikes and let them proceed to the target area in the hope that they would find suitable targets.

The light cruiser Yubari was present at the Coral Sea as flagship of Destroyer Flotilla 6. This ship was completed in 1923 as an experimental design to mount the armament of a 5,000-ton light cruiser on a hull of only 2,900 tons. (Yamato Museum)

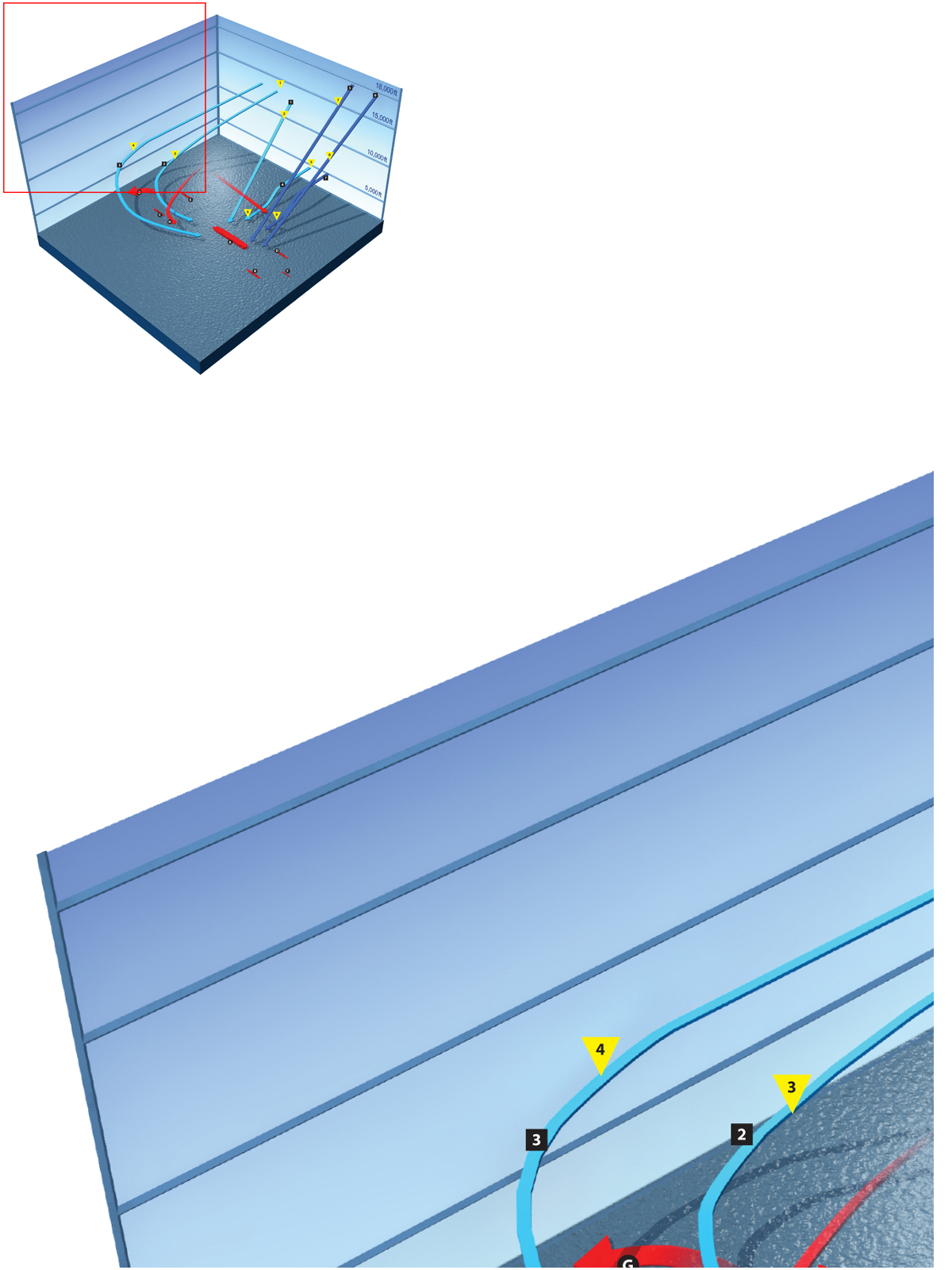

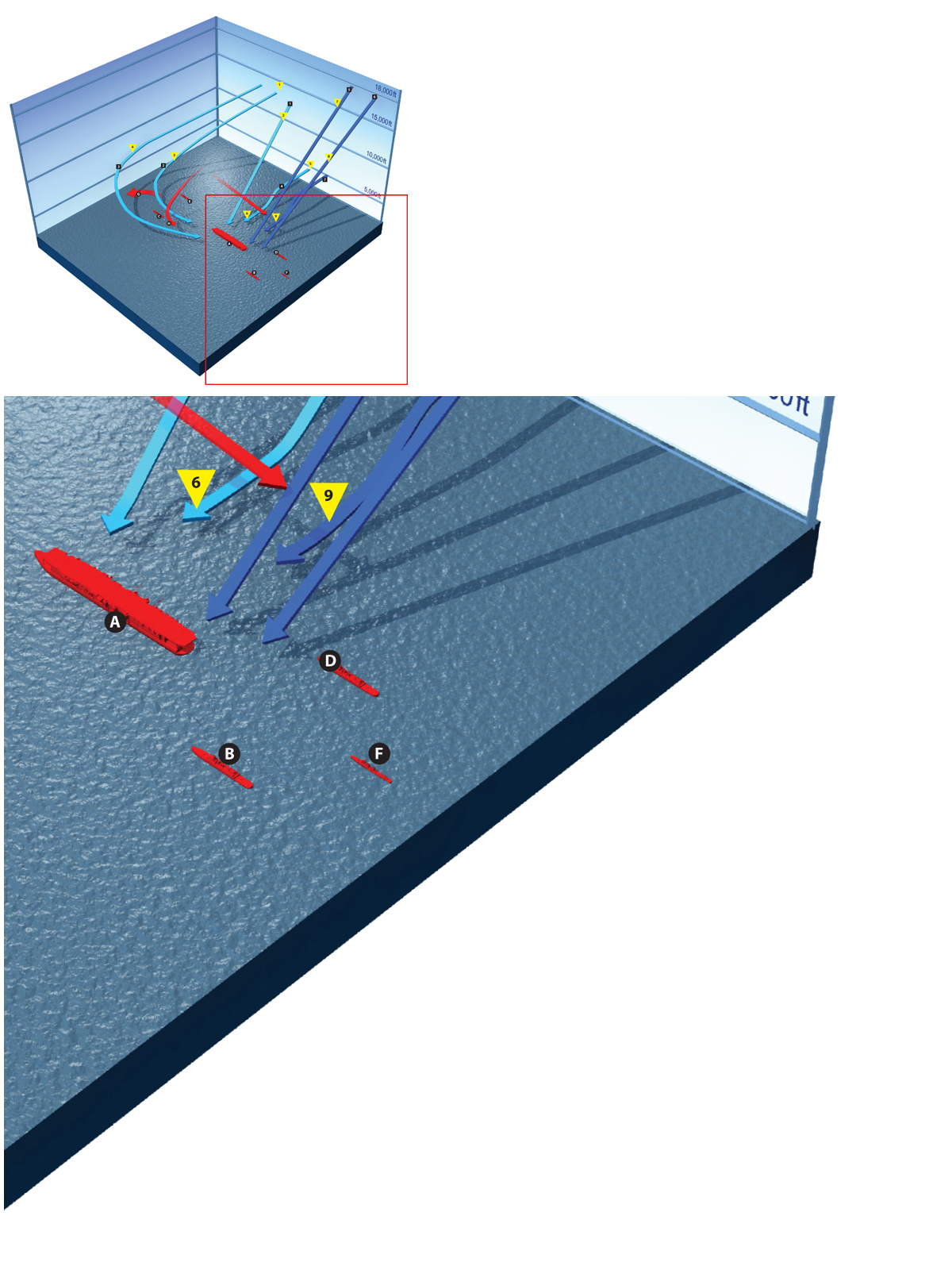

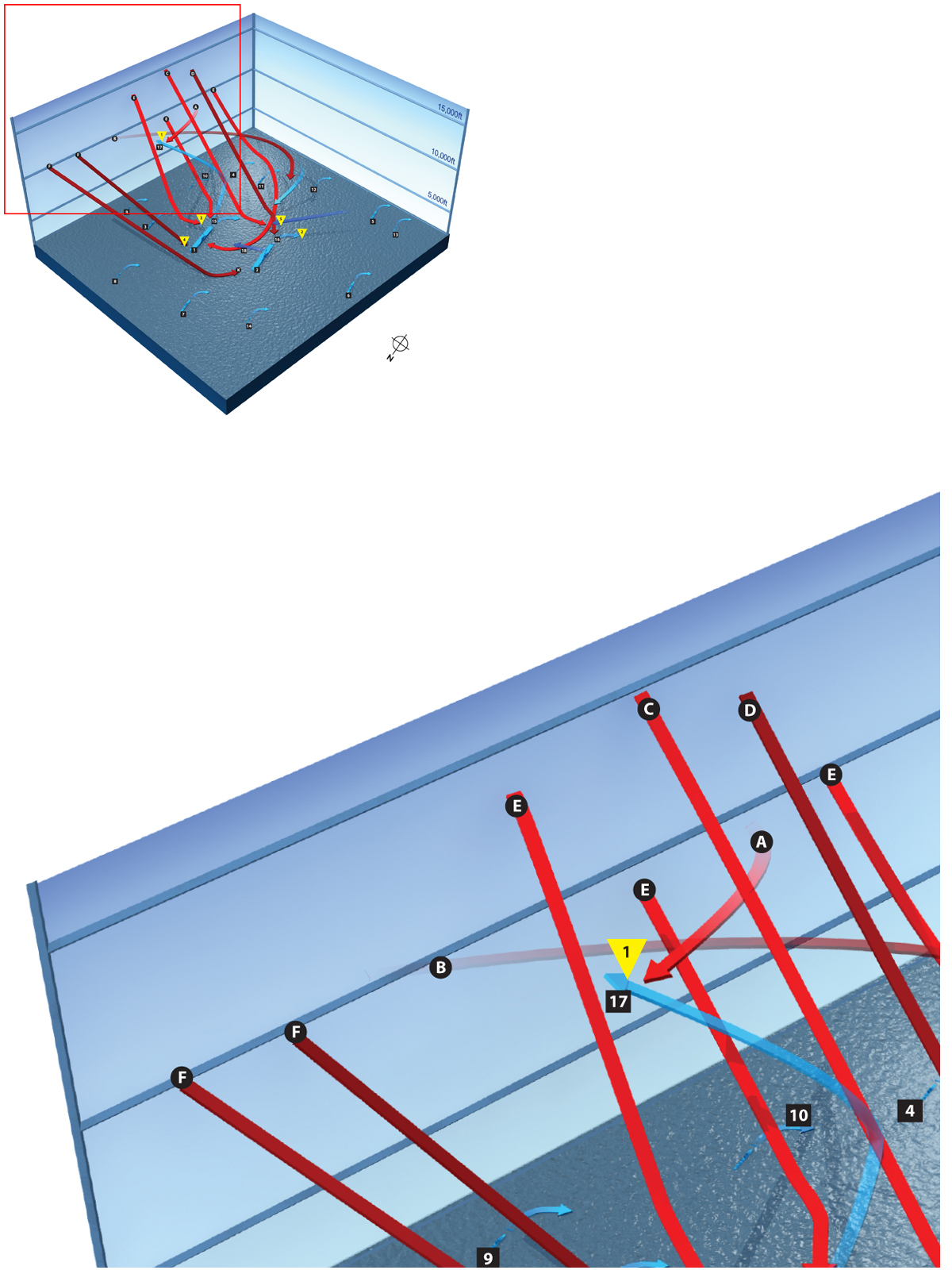

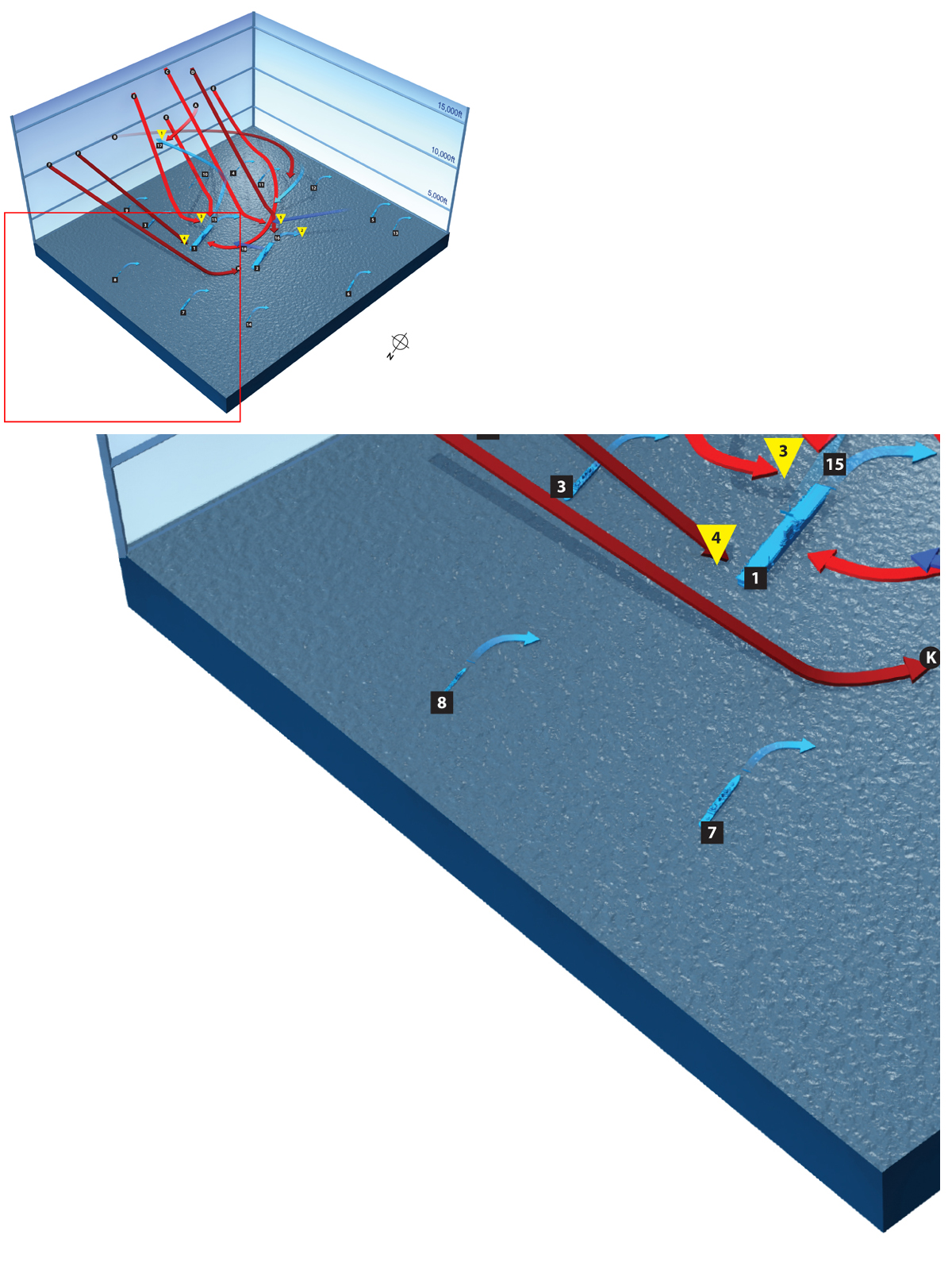

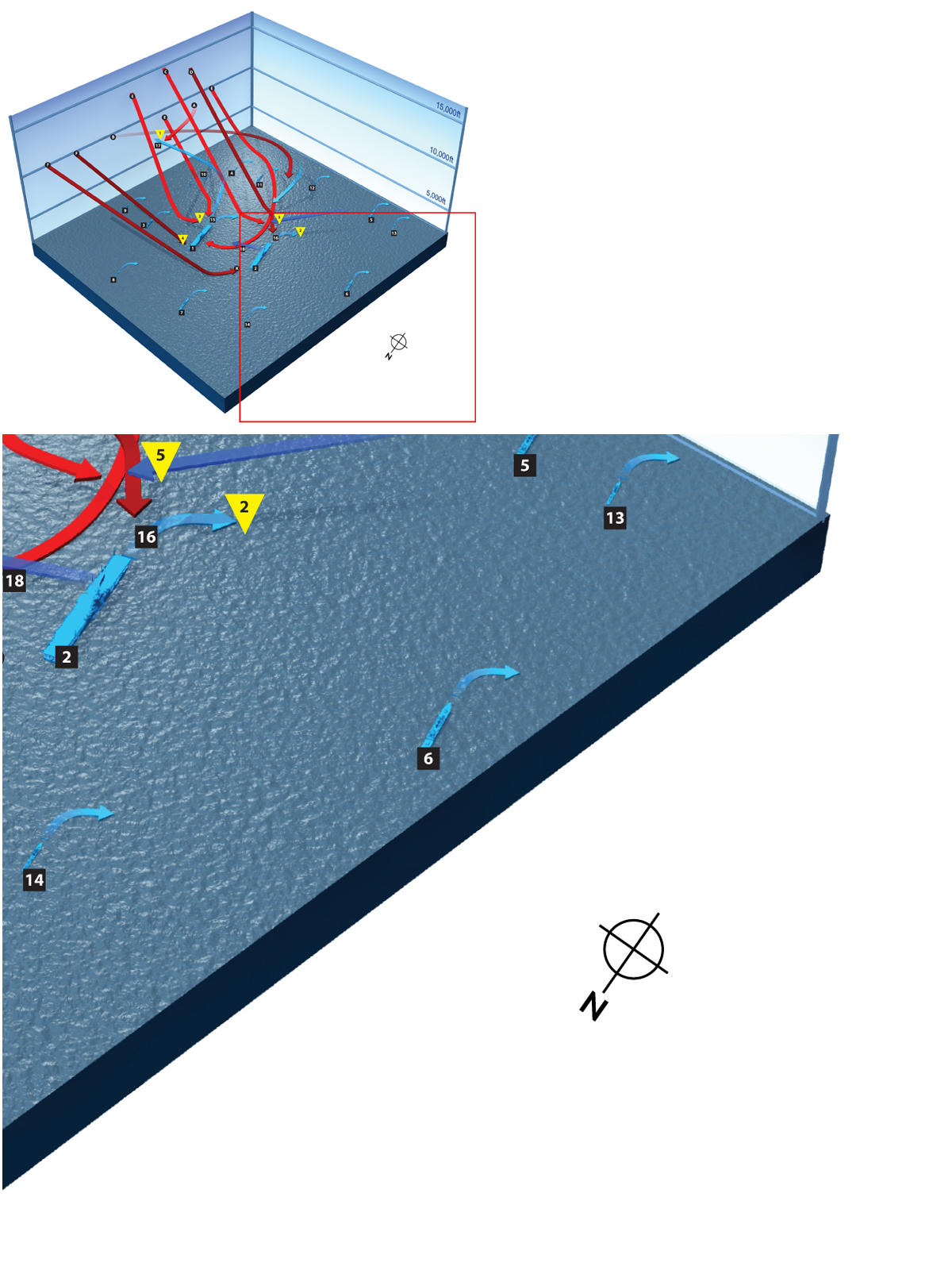

AMERICAN FORCES:

Lexington Air Group

1. Lexington Air Group command section (three SBD) and two VF-2 F4F fighters

2. VS-2 (ten SBD-3)

3. VB-2 (15 SBD-2/3) and four VF-2 F4F fighters

4. VT-2 (12 TBD-1) and four VF-2 F4F fighters Yorktown Air Group

5. VS-5 (17 SBD-3) and three VF-42 fighters

6. VB-5 (eight SBD-3)

7. VT-5 (ten TBD-1) and five VF-42 F4F fighters

JAPANESE FORCES:

A Shoho

B Furutaka

C Kinugasa

D Kako

E Aoba

F Destroyer Sazanami

G CAP on station before attack began (one A6M Zero and A5M Type 96 Claude)

H CAP launched at 1107hrs (three A6M Zero)

EVENTS

EVENTSAttack of the Lexington Air Group

1. 1040hrs: Shoho spotted 40 miles to the north. Commander Ault prepares a coordinated attack. His command element and VS-2 head straight into an attack on the carrier to soften its defenses. VB-2 swings to the east to mount a coordinated attack with the slower Devastators of VT-2.

2. 1110hrs: Ault begins dive from 10,000ft. All three command section aircraft miss.

3. 1110–1117hrs: VS-2 moves around to north to take advantage of sun and wind direction and then dives from 12,500 feet against light antiaircraft fire. Two Japanese A5M fighters attack the lead elements with no result. Shoho continues a turn to port to complete a circle making VS-2 attack from astern. Ten aircraft drop 500-pound bombs at 2,000ft but all miss. The single A6M fighter on CAP damages one SBD on its dive and shoots down another while pulling out of its dive. The two A5Ms attack and damage several SBDs after completion of the attack. A single VS-2 aircraft attempts a second dive on an escort ship with its 110-pound bombs without success.

4. 1118hrs: VB-3 starts dive from 12,000ft, just as Shoho completes her second full circle. Attacked by an A5M on the way down, the squadron commander, LCDR Hamilton, scores a 1,000-pound bomb hit just forward of the elevator. One additional hit is scored further forward. Massive fires break out on Shoho’s hangar deck fed by fueled aircraft. No Dauntlesses are lost.

5. 1115–1119hrs: VT-2 descends from 4,000ft to 100ft to release torpedoes. Shoho sights aircraft off starboard quarter and turns to starboard to avoid. VT-2 heads through gap between two cruisers to attack the carrier on her beam. When Shoho continues a port turn, the squadron is set up for an anvil attack. Two A5M fighters attack torpedo planes on final approach, but are intercepted by Wildcats.

6. 1119hrs: VT-2 commanding officer launches first torpedo from Shoho’s port quarter. Five hits are scored (nine are claimed) and includes a hit which disables Shoho’s steering keeping the ship on a southeasterly course. The torpedo damage is fatal, creating a list and uncontrolled flooding.

Attack of the Yorktown Air Group

7. 1125hrs: the commander of the dive-bombers decides to press his attack immediately without waiting for the slower torpedo planes. Seventeen VS-5 aircraft attack with 1,000-pound bombs claiming nine hits against the non-maneuvering Shoho. Three A6Ms attack with no effect.

8. 1130hrs: eight VB-5 SBDs attack, claiming six hits. The Japanese confirm that as many as 11 hits were scored by Yorktown dive-bombers. The last Yorktown aircraft actually attacks a cruiser when it is evident that Shoho is doomed. Two VB-5 aircraft are damaged by A6Ms.

9. 1129hrs: VT-5 begins attack on Shoho’s starboard side. All ten aircraft claim hits; the Japanese confirm two but more are likely. Two A5M fighters attack the vulnerable Devastators after their attack. Both are shot down by escorting Wildcats and another Zero is also destroyed.

While Fletcher was concerned he had missed the main Japanese carrier force, his strike was headed into an area rich with targets. With the MO Invasion Force and the Main Force all located fairly close together and the weather in the area very clear, there was no chance the Americans’ strike would be entirely fruitless. In response to the American air activity, Inoue had turned the invasion convoy to the north to avoid air attack. He knew his force had been spotted and that American carriers were located to the southeast. He also had received reports of a force of two battleships a cruiser and four destroyers (Crace’s force) located south of the Jomard Passage. Until Hara’s carriers could deal with these threats, he stopped his advance. In the meantime, Shoho would have to defend his force from expected air attack.

Located in clear weather, and with a total of 93 American aircraft headed her way, Shoho’s first and last battle was destined to be a quick one. Lexington’s aircraft spotted her around 1040hrs about 40 miles to the north. Shoho had just landed her four-plane CAP and a carrier attack plane, and was preparing to launch a small strike on TF-17. When the American strike was spotted at 1050hrs, a total of one Type 0 and two Type 96 fighters were airborne.

Lexington’s air group was the first to attack and conducted one of the best-coordinated attacks by any US carrier during the entire war. The air group commander, Commander William Ault, opted to lead his command element and VS-2 straight in against the carrier to soften its defenses while the remainder of the air group set up for a coordinated attack. Opening the attack at 1110hrs, Ault’s three dive-bombers all missed. Shoho conducted a sharp turn to port to evade her attackers, and this was successful in making all ten VS-2 aircraft miss as well. Japanese anti-aircraft fire was ineffective as were the attempts of the two Type 96 fighters against the diving Dauntlesses. The single Type 0 fighter on patrol was able to damage a Dauntless during its dive and shoot down a dive-bomber pulling out of its dive. At 1118hrs, VB-2 commenced its attack and scored two hits forward with 1,000-pound bombs. These caused massive fires on the hangar deck that were fed by the fueled aircraft being readied for the strike against TF-17. Simultaneously with the dive-bomber attack, VT-2 descended to its attack altitude of 100ft. Finding a gap in the cruiser screen, the commander of the squadron dropped his torpedo at 1119hrs. Five hits were gained, enough to cause fatal damage owing to uncontrolled flooding.

Lacking an overall strike commander, the Yorktown’s aircraft arrived to begin their attack on the listing and smoking Shoho though it should have been apparent she was already doomed. Beginning at 1125hrs, 24 of 25 dive-bombers from VB-5 and VS-5 attacked Shoho. Fifteen hits were claimed against the non-maneuvering target and Japanese sources confirm as many as 11 hits. This brought Shoho dead in the water. At 1129hrs, VT-2 torpedo planes attacked and claimed ten hits. Japanese confirmed two, but more were likely. Shoho had been literally torn apart by a barrage of bombs and torpedoes. Of her crew of 834, only 203 survived. US losses were one Dauntless from Yorktown and two from Lexington.

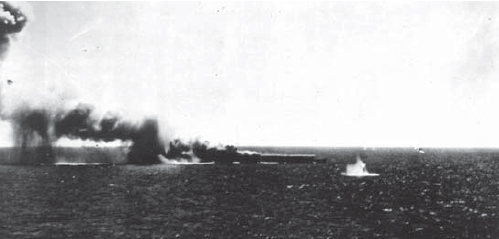

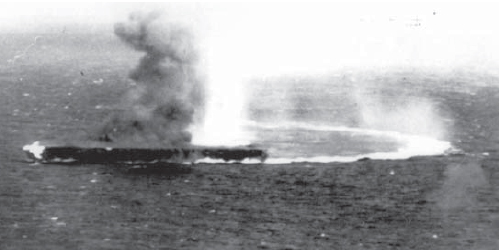

A remarkable action shot of Shoho under attack by American torpedo bombers on May 7. Shoho is already burning from dive-bombing damage. A Devastator can be seen turning away at right as its torpedo strikes the water below. (US Naval Historical Center)

By 1450hrs, both American air groups had recovered and were spotted on their carriers for additional strikes. Fletcher’s aviators had done a good day’s work, sinking the first Japanese carrier of the war. Given the impossibility of launching and recovering a strike before dark, and the bad weather in the area, Fletcher decided not to launch a second strike against Japanese units in the Solomon Sea or to launch additional searches for the main Japanese carrier force. Fletcher was aware of Inoue’s retreat with the invasion convoy, but was still unaware of the location of the Japanese carriers. He was relieved that his misstep earlier in the day did not bring a punishing Japanese carrier strike.

While Fletcher may have escaped a Japanese air attack, TG-17.3 did not. Crace’s force was operating throughout the day to the southeast of the Jomard Passage, placing it within range of Japanese land-based aircraft from Rabaul. Crace’s force had been spotted earlier in the day, and at 1400hrs two waves of G3M Type 96 attack bomber (Allied codename “Nell”) aircraft arrived from Rabaul to deliver attacks. In the first wave, 12 G3Ms equipped with torpedoes were unsuccessful in scoring a single hit when they launched at excessive range. Five aircraft were lost. Approximately a half-hour later, 19 additional G3Ms delivered a high-altitude bomb attack, again scoring no hits. Crace’s skillful maneuvering and heavy anti-aircraft fire had avoided disaster, but the Japanese were still confident they had scored heavily. They claimed a California-class battleship and an Augusta-class cruiser sunk, a Warspite-class battleship heavily damaged and possible damage to a Canberra-class cruiser. Both the skill and the recognition abilities of the Japanese aviators were dismal and contrasted poorly with the Japanese Naval Air Force strikes of only a few months earlier, when land-based aircraft had quickly sunk the Royal Navy’s capital ships Prince of Wales and Repulse off Malaya in the first few days of the war.

Lexington’s air group was the first to attack Shoho. Shown here is one of the five torpedo hits scored by Lexington Devastators. The ship is already burning as the result of two 1,000-pound hits. (US Naval Historical Center)

After dodging the bombs of the first 13 Lexington dive-bombers to attack, the Shoho’s luck began to run out. At 1118hrs, the commanding officer of VB-2, Lieutenant-Commander Weldon Hamilton (1), led his squadron into a dive from 12,000ft on the desperately maneuvering Japanese light carrier. The ship continued a hard turn to port and completed her second full circle. Though Hamilton was attacked by a Japanese Type 96 fighter during his dive, at 2,500ft he released his 1,000-pound bomb which impacted on the center of Shoho’s flight deck just forward of the aft elevator (2). This was the first American damage on Shoho and the first scored on any Japanese carrier in the entire war. Hamilton’s squadron scored an additional bomb hit, which caused massive fires to break out on Shoho’s hangar deck fed by fueled aircraft being prepared for a strike. The ship was subjected to a further deluge of torpedoes and bombs from other Lexington and Yorktown aircraft and sank shortly thereafter with a heavy loss of life.

With the loss of Shoho, Inoue delayed the Port Moresby landings by two days. He moved the invasion convoy out of range and concentrated his surface combatants off Rossel Island to prepare for a possible night attack. Realizing this was not realistic, he later instructed Goto to split his cruiser force and keep two ships with the Main Force and send the other two to aid the Carrier Striking Force. The attack on Shoho did succeed in putting a greater sense of urgency into Takagi and Hara. Given the number of aircraft involved in the attack on Shoho, it was clear that two American carriers were on the loose. With the MO Operation in shambles, everything depended on the ability of the Carrier Striking Force to sweep the American carriers from the scene and get the operation back on schedule. Accordingly, Hara was now inclined to take risks. Since he had received no recent locating data on the American carriers, Hara ordered a search from the southwest to northwest out to 200 miles. These aircraft were launched at 1530hrs but gained no contact before being ordered to return. This search was intended to guide a risky dusk strike by the most experienced Japanese crews. From Zuikaku, nine carrier attack aircraft and six carrier bomber crews were selected to participate, joined by six more carrier attack aircraft and six carrier bombers from Shokaku. The fact that there was more than a small degree of desperation involved in this venture was obvious. Some of the crews had just returned from a seven-hour strike earlier in the day and now these crews were expected to take off again in increasingly terrible weather conditions to conduct a strike against an unlocated target.

Haguro was assigned to the MO Carrier Striking Force. With four dual 5in. mounts and four 25mm dual mounts, the Myoko-class cruisers were only marginally capable of providing anti-aircraft screening to the carriers. (Yamato Museum)

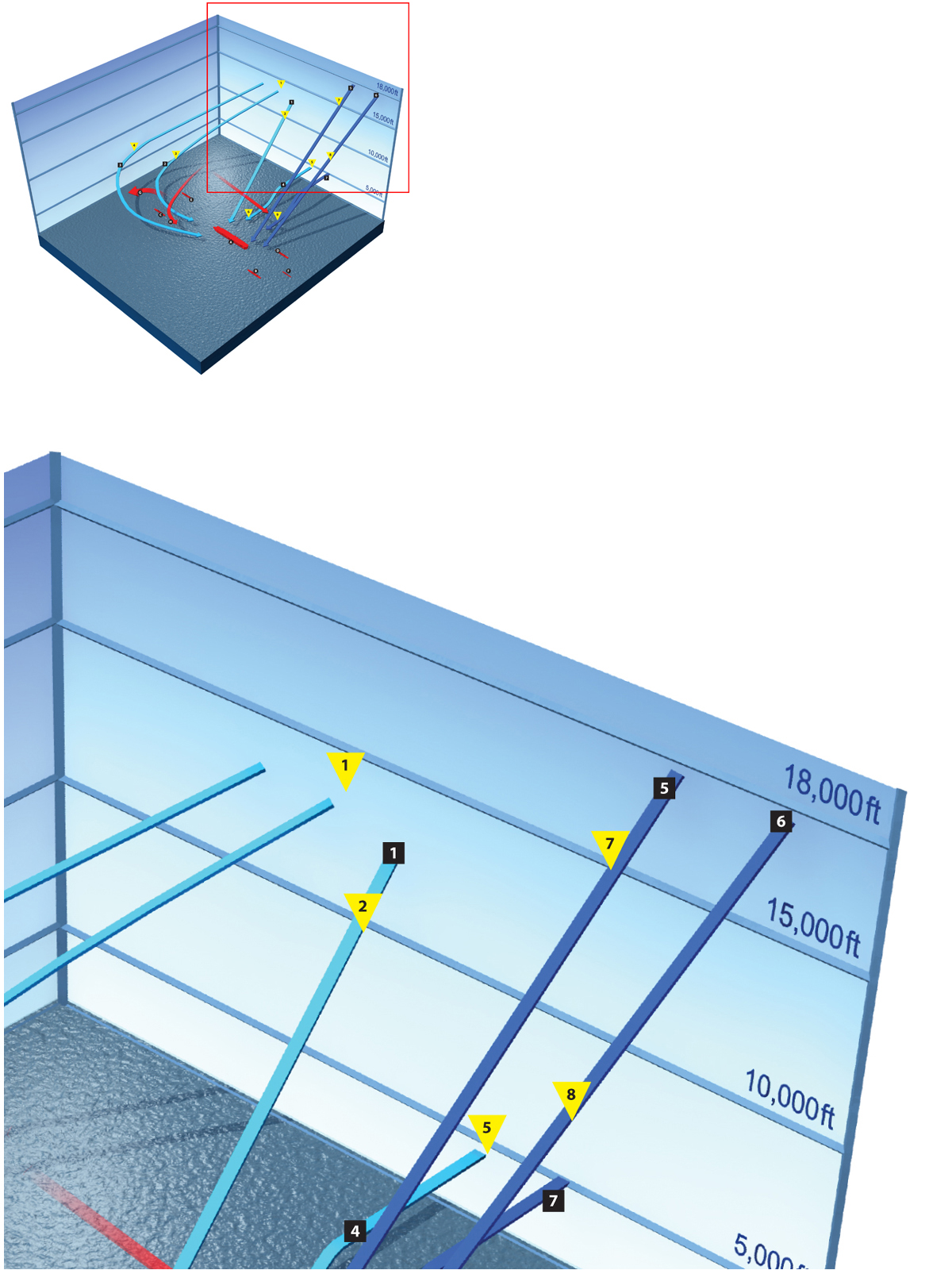

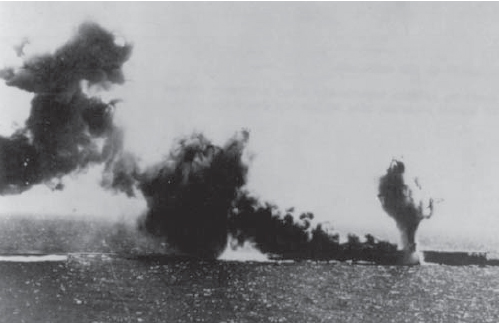

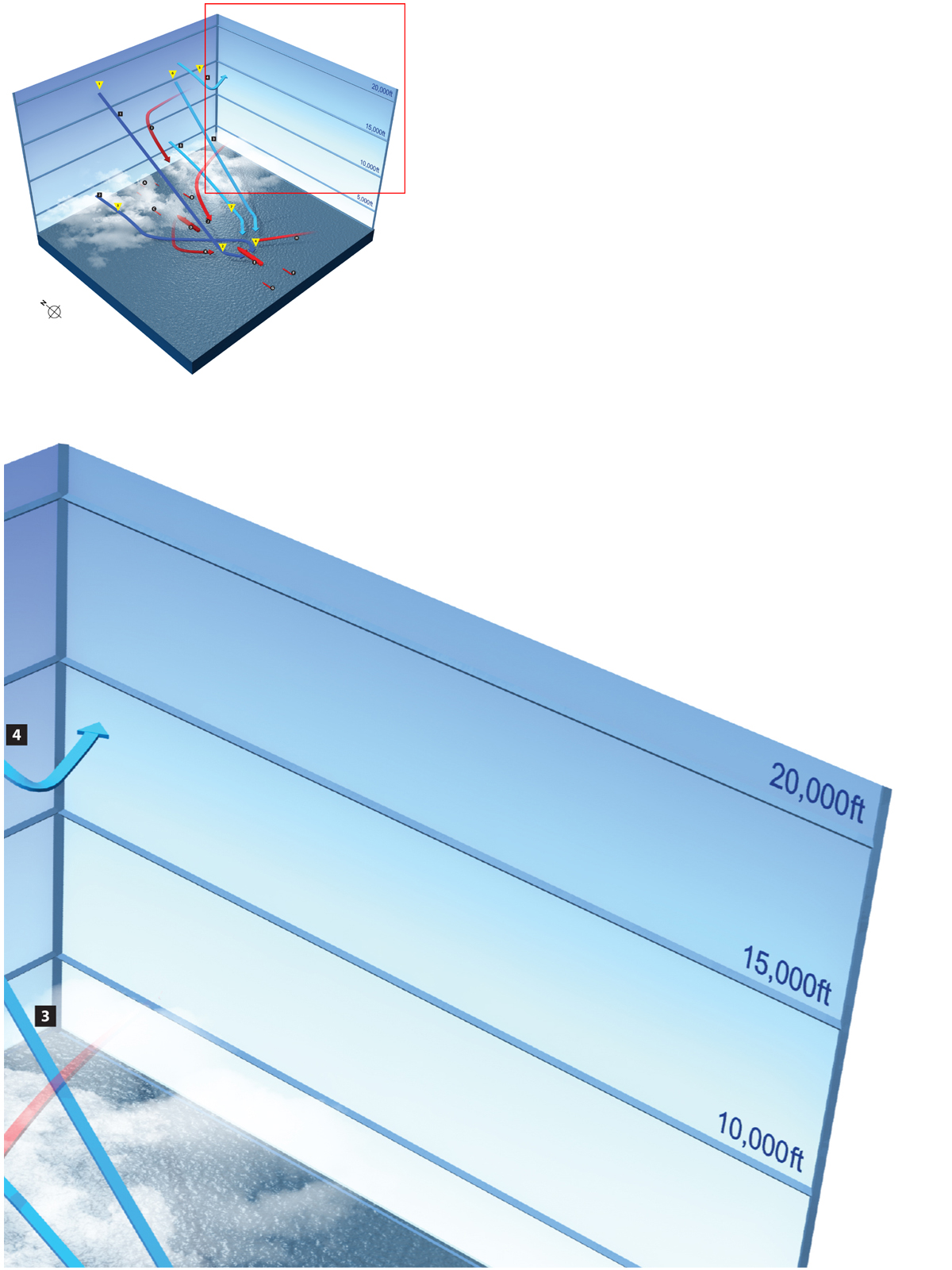

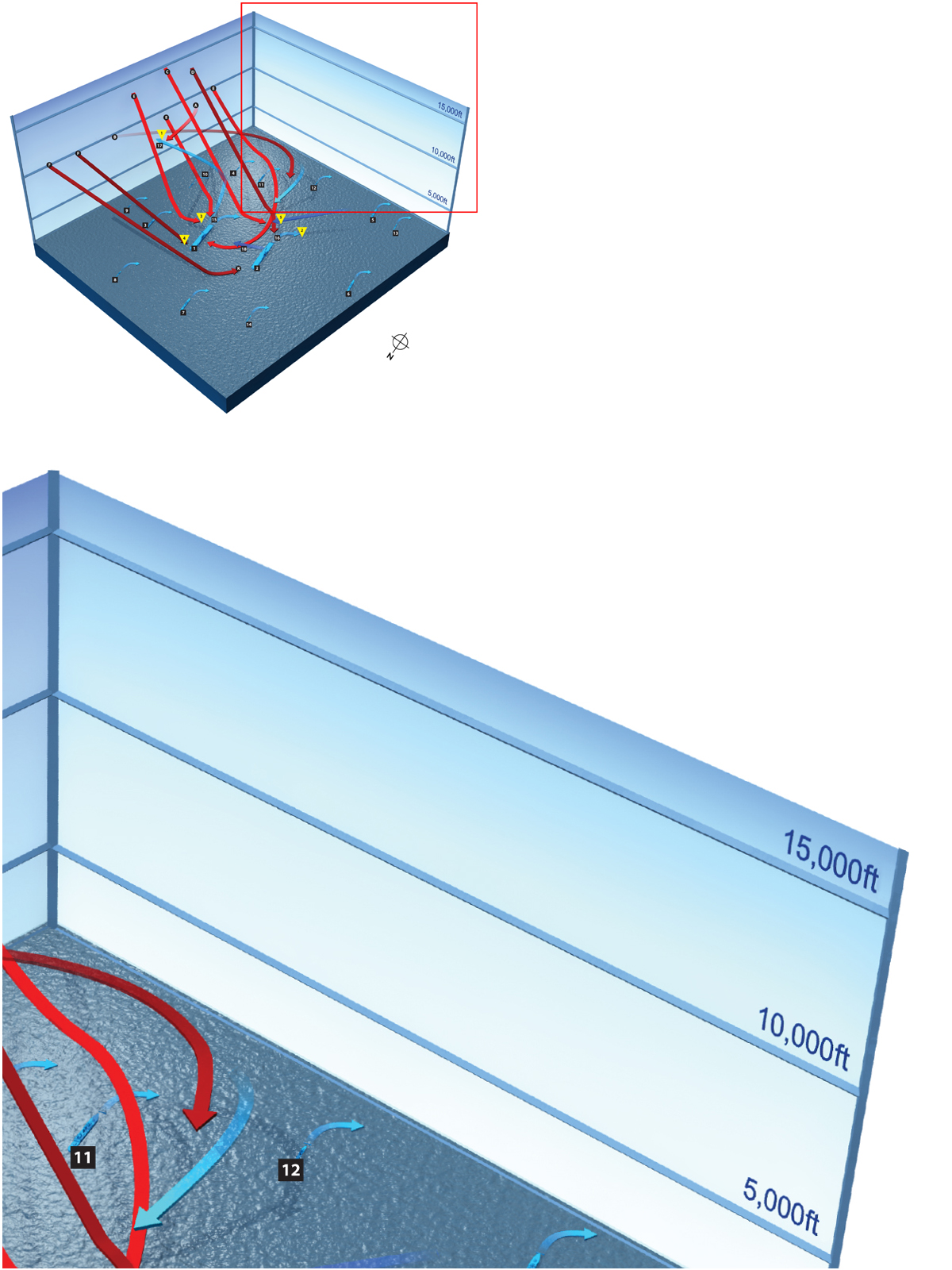

JAPANESE FORCES:

A Destroyers (three)

B Myoko

C Haguro

D Zuikaku

E Shokaku

F Kinugasa

G Furutaka

H A6M Zero CAP (three above Shokaku at 13,000ft)

I A6M Zero CAP (three above Zuikaku at 20,000ft)

J A6M Zero CAP (three launched from Shokaku at 1049hrs)

K A6M Zero CAP (four launched from Zuikaku at 1049hrs)

AMERICAN FORCES:

1 Yorktown dive-bomber group (seven VS-5, 17 VB-5 SBDs and two VF-42 fighters)

2 Yorktown torpedo plane group (nine VT-5 TBDs escorted by four VF-42 fighters)

3 Lexington command section (four SBDs (Commander Ault’s aircraft plus three from VS-2, escorted by two VF-2 fighters)

4 Lexington dive-bomber group (11 VB-2 SBD escorted by three VF-2 fighters)

5 Lexington torpedo plane group (11 VT-2 TBDs escorted by four VF-2 fighters)

EVENTS

EVENTSYorktown Air Group attack

1. 1049hrs: Yorktown SBDs wait at 17,000ft southeast of Japanese carriers for VT-5 to arrive at attack position for coordinated attack. American aircraft are finally spotted by Japanese who launch seven ready CAP aircraft.

2. 1100hrs: Dive-bombers attack; only Shokaku is visible at this time. All seven VS-5 aircraft miss in large measure due to fogged sights and windscreens as they encounter warm, moist air at 8,000ft. Attacked by three Zuikaku A6Ms at 11,000ft; several SBDs are damaged, one badly. Four additional Zuikaku A6Ms, just launched, attack the SBDs as they withdraw.

1103hrs: VB-5 begins dive. Rear division attacked by A6Ms from Shokaku CAP and SBDs encounter same fogging problem.

1105hrs: First hit on the Shokaku’s port side forward creating fire on her bow. Second hit is scored on starboard side near island that ignites additional fires on flight and hangar decks. Hit is scored by Lt. John Powers who takes his SBD well under 1,000ft to ensure a hit.

3. 1103hrs: VT-5 starts attack on port beam and bow of Shokaku flying at 110 knots at 50ft. Attacks by six A6Ms (three each from Shokaku and Zuikaku) are defeated by VF-42 and at least one A6M is shot down.

4. 1108hrs: VT-5 releases torpedoes 1,000–2,000 yards from Shokaku just as VB-5 is finishing its attack. No hits are scored; one TBD damaged by anti-aircraft fire.

Lexington Air Group attack

5. 1130hrs: the Lexington strike spots the MO Carrier Striking Force after executing a box search after failing to find the enemy at the briefed position. The squadrons in Lexington’s strike became separated in the bad weather. Only four dive-bombers, 11 torpedo planes escorted by six fighters are available to attack. At this point, the Japanese have 11 A6Ms on CAP. Shokaku has four A6Ms at 13,000ft; Zuikaku has three fighters at 19,000ft and four more at low altitude assigned to watch for torpedo planes

6. 1140hrs: Ault’s four SBDs attack first to draw Japanese CAP to protect the slow TBDs. The dive-bombers choose to conduct a glide-bomb attack as they are not at the proper altitude for a dive-bomb attack. The three high Zuikaku A6Ms attack the SBDs at 5,500ft, but three of the four dive-bombers drop their 1,000-pound bombs (one hangs on the aircraft) and one hit is scored. The two escorting Wildcats cover their retreat. In the fighter clash, one Shokaku A6M is shot down with one Wildcat possibly destroyed.

7. 1142–1150hrs: VT-2 attacks escorted by four Wildcats. The four Zuikaku A6Ms at low altitude shoot down two Wildcats, but are unable to get to the TBDs. The first two TBDs come in on Shokaku’s port bow. In response, Shokaku executes a hard turn to starboard to present her stern to the torpedo planes. Despite dropping from only 400–600 yards, both miss. The remainder of VT-2 attacks Shokaku from her starboard side after Shokaku completed a 180-degree turn. Shokaku turns away to outrun these torpedoes and all miss.

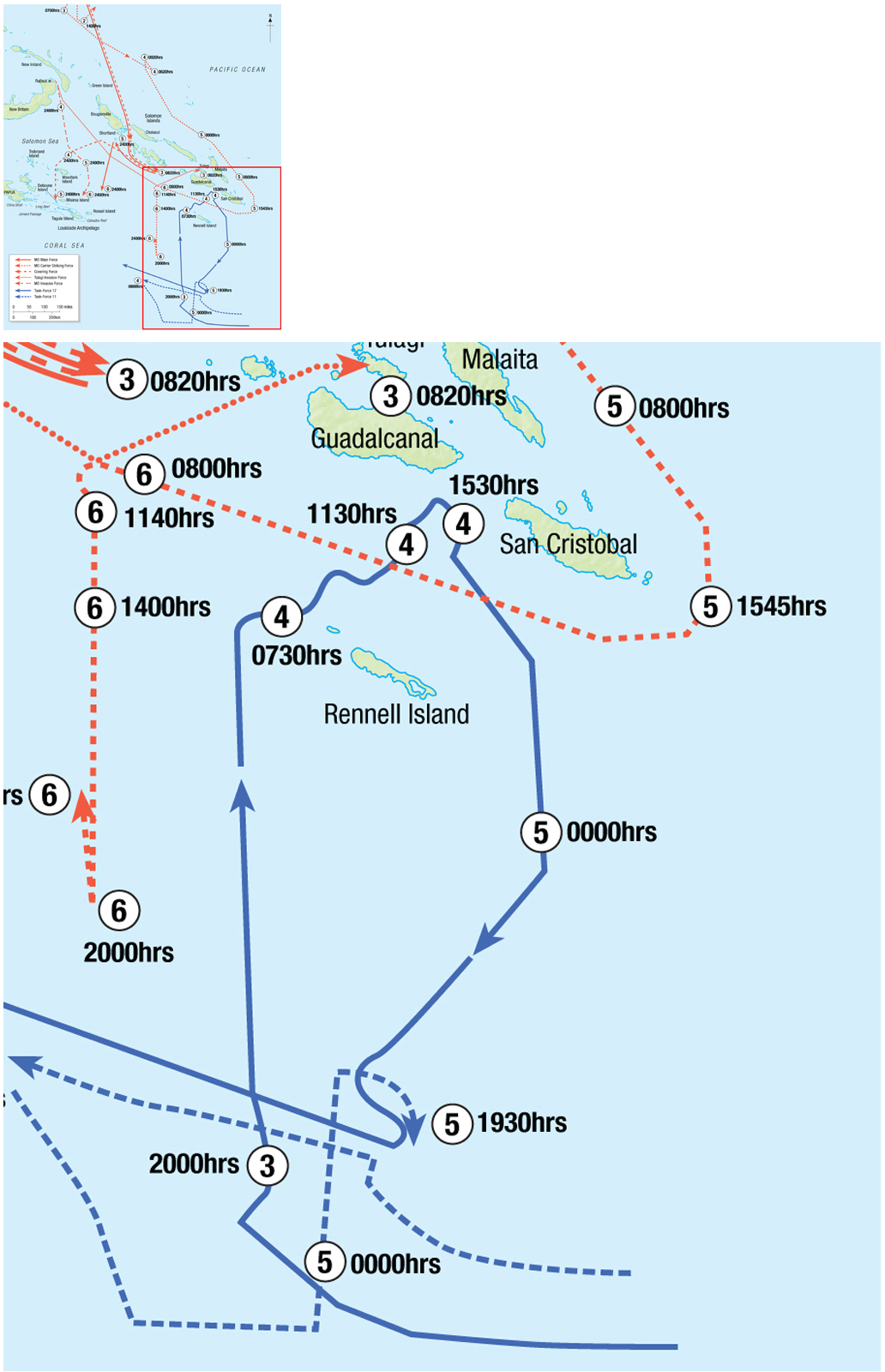

Predictably, the operation did not go well. The aircraft left the decks of their carriers starting at 1615hrs and were briefed to go to a point 280 miles west to search for the enemy. Unknown to the Japanese, the American carriers were only some 150 miles to the west-northwest but hidden under heavy clouds. When the Japanese strike arrived at its designated area, nothing was there. After an incomplete reconnaissance of the area, the aircraft headed home in three groups after jettisoning their ordnance. On their return, the Japanese ran afoul of the US carriers. Wildcats directed by radar intercepted the first group, and six carrier attack planes and one carrier bomber were shot down for the loss of three Wildcats. The second and third group arrived over the American carriers in the dark and, certain they were their own ships, attempted to land. Anti-aircraft fire from the Americans accounted for one carrier attack plane and cleared up any confusion on the part of the Japanese. Finally, by 2300hrs, the Japanese aircraft recovered with one additional carrier attack plane ditching. Of the 27 aircraft launched, 18 returned, a remarkable achievement. However, the loss of eight precious carrier attack planes would be felt the next day. Once debriefed, the Japanese aviators reported that TF-17 was a mere 40–60 miles to the west. Both sides now knew the other was close. The next day would certainly bring the deciding clash of the battle.

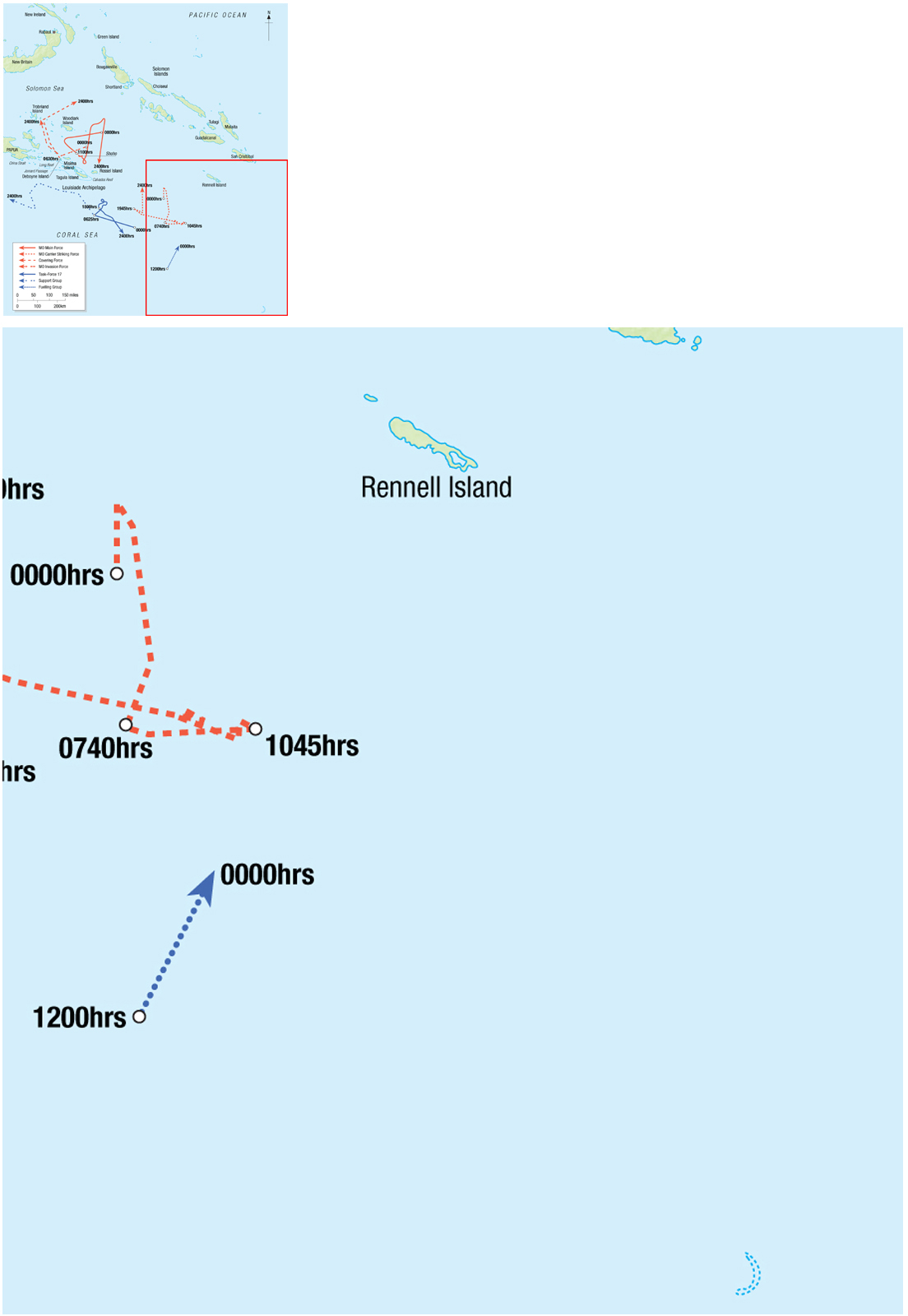

Both sides knew that quick and accurate reconnaissance was the key to deciding events on May 8. During the night, both sides attempted to place themselves in a favorable position for the forthcoming battle. The American carriers moved southeast until after midnight and then turned to the west. The destroyer Monaghan was detached to rescue survivors from Neosho and Sims. This left TF-17 with seven destroyers. Crace ordered his force to head west in order to remain southeast of Port Moresby in position to intercept any Japanese forces advancing on Port Moresby in the wake of the carrier battle.

On the morning of May 8, TF-17 possessed 117 operational aircraft (31 fighters, 65 dive-bombers, and 21 torpedo bombers). For the morning search, Fitch devised a plan to cover all contingencies. Because he could not be certain about the movement of the Japanese carriers during the night, he had to assume the possibility that they could still be relatively close by. Therefore, a full 360-degree search was required which would take 18 SBDs from Lexington’s VS-2 and VB-2. The northern part of the search pattern was carried out to 200 miles while the southern part was limited to 125 miles. Upon their return, these 18 aircraft would be devoted to anti-torpedo bomber patrol. Each carrier allocated eight fighters for CAP missions during the day and Yorktown dedicated eight SBDs for anti-torpedo bomber patrols. On both carriers, the remaining aircraft were spotted ready to conduct the strike when locating information was received.

Lexington viewed from Yorktown on May 8. Note the Dauntless dive-bombers onboard the Yorktown. (US Naval Historical Center)

Zuikaku in 1941. At this point, she was virtually identical to her sister ship. With the exception of Midway, Zuikaku participated in every carrier battle of the war. (Yamato Museum)

During the night of May 7/8, Inoue ordered Takagi to take his carriers to a point 110 miles south-southeast of Rossel Island by dawn to be in position to engage TF-17. However, for a number of reasons, dawn found the MO Carrier Striking Force in a position 140 miles northeast of Rossel Island. Since the failed night strike was so long in returning, the Japanese carriers had to steam to the east to recover aircraft until 2200hrs. Hara advised Takagi to keep heading east or to head south in order to hit the American carriers from the flank. Takagi rejected this recommendation, but did concur with Hara’s recommendation to move the MO Carrier Striking Force’s dawn position northeast of Rossel Island contrary to Inoue’s orders. Hara thought this position would allow him to conduct a more refined search rather than an omni-directional search if he obeyed Takagi’s orders and proceeded to the area southeast of Rossel Island, which was close to the last position of the American carriers. Hara’s plan meant that fewer aircraft were required to conduct searches and more aircraft were devoted to strike missions.

Hara’s aircraft situation on the morning of May 8 was not as favorable as Fitch’s. Carrier Division 5 possessed 96 operational aircraft – 38 fighters, 33 carrier bombers and 25 carrier attack planes. Compared with TF-17, the MO Carrier Striking Force could muster 21 fewer aircraft, with the primary difference being the marked American edge in dive-bombers. In contrast to Fitch, Hara’s search plan was more austere. According to IJN search doctrine, he preferred to use cruiser floatplanes to conduct search missions saving the carrier aircraft for strike duties. However, on May 8, rough seas prevented the Japanese cruisers from contributing their aircraft. Hara was forced to devote seven carrier attack planes to cover the southern arc from his carriers out to a distance of 250 miles. Four land-based bombers from Rabaul and three flying boats from Tulagi were tasked to search south of the Louisiades.

By 0600hrs, the MO Carrier Striking Force was located some 220 miles northeast of TF-17 under heavy weather. Takagi continued to head north to meet with the cruisers Kinugasa and Furutaka, detached by Inoue from the MO Main Force to augment the screen of the carrier force. The rest of the elements of the MO operation, including the Main Force, the Invasion Force and the Covering Force, were ordered to gather 40 miles east of Woodlark Island in the afternoon. After the MO Striking Force had cleared the way, the convoy would proceed to Port Moresby to conduct the invasion now scheduled for May 12.

Weather played an important role in the events of May 8. The edge of the weather front had moved 30–50 miles to the north and northeast. This brought TF-17 out from under the heavy weather that offered a degree of protection from enemy reconnaissance and placed it in an area of light haze with greatly increased visibility. Conversely, the Japanese carriers now operated in an area of heavy weather with thick clouds and squalls. As later was the case, this made the job of American aviators more difficult.

Japanese search aircraft were in the air by 0615hrs, followed by the 18 TF-17 SBDs at 0635hrs. It did not take long for each side to find what they were looking for. The Japanese were the first to have success. At 0802hrs, Yorktown’s radar reported a contact 18 miles to the northeast, but TF-17’s CAP was unable to find or intercept the snooper. At 0822hrs, a report was issued by the Japanese search plane that two American carriers had been spotted and reported at 235 miles from the MO Striking Force on a bearing of 205 degrees. Radio intelligence units on both Lexington and Yorktown both confirmed the fact that the Japanese aircraft had spotted TF-17 and had issued a report.

The first report received by Fletcher and Fitch was at 0820hrs when a VS-2 SBD spotted the MO Carrier Striking Force in bad weather. When plotted out, the contact was 175 miles from TF-17 on a bearing of 028 degrees and was headed away from the American carriers. At 175 miles, the Japanese carriers were at the edge of the striking range of the TBDs; nevertheless, it was decided to launch a full strike and head TF-17 toward the contact to reduce the distance the strike would have to fly back to their home carriers.

The Americans were the first to get their strikes in the air. At 0900hrs, the Yorktown began launching her strike of 39 aircraft (six fighters, 24 dive-bombers and nine torpedo bombers) followed at 0907hrs with a 36-aircraft strike from the Lexington (nine fighters, 15 dive-bombers and 12 torpedo bombers). With the air battle now beginning, at 0908hrs Fletcher gave Fitch tactical control of TF-17. By 0925hrs, the two American air groups had departed the area of TF-17 to proceed to strike the Japanese. Per American doctrine, the two air groups were widely separated with no single strike commander. Additional reports from a VS-2 aircraft at 0934hrs placed the Japanese carriers 191 miles from TF-17. Immediately after recovering his morning reconnaissance aircraft, Fitch planned to head to the northeast to reduce the distance to the Japanese carriers.

Shokaku under attack by dive-bombers from Yorktown. Shokaku is making a highspeed starboard turn in an effort to spoil the aim of her attackers. Note the virtual lack of anti-aircraft fire and the absence of any nearby Japanese escort ships. (US Naval Historical Center)

Shokaku shown at high speed conducting a series of sharp evasive turns under attack by Yorktown dive-bombers. A large fire can be clearly seen burning fiercely in the bow section of the ship. The heavy black smoke amidships suggests that Shokaku has also been hit by the second 1,000-pound bomb scored by Yorktown’s Dauntlesses, which struck near the island and started large fires on the flight and hangar decks. (US Naval Historical Center)

When the Yorktown strike arrived in the area of the MO Carrier Striking Force, the Japanese force was separated into two sections. Zuikaku, escorted by Myoko and Haguro and three destroyers, was some 11,000yds ahead of the Shokaku with her two cruisers, the Furutaka and Kinugasa, trailing another 11,000yds astern. As the dive-bombers maneuvered into position for attack, the Zuikaku group disappeared into a squall. Only a single fighter from the Yorktown group even saw Zuikaku. Shokaku, remaining in an area of clear visibility, took the brunt of Yorktown’s attack. The 24 SBDs scored two hits with 1,000-pound bombs. The first hit on the port bow started a fire in the forecastle. The second hit the starboard side of the ship near the island and started fires on the flight and hangar decks. The attack of VT-5 was completely futile with all nine torpedoes being dropped too far from their target and all missing. Japanese CAP aircraft and anti-aircraft fire proved to be almost totally ineffective. Two SBDs were lost, but VF-42 Wildcats shot down two Type 0 fighters attempting to prevent VT-5’s unsuccessful attack.

A view taken from a Devastator from VT-5 of the attack on Shokaku on May 8. Yorktown’s air group delivered a well-coordinated attack, but achieved only two bomb hits. None of the nine Devastators that dropped their torpedoes scored a hit. (US Naval Historical Center)

Some 30 minutes after the start of Yorktown’s attack, Lexington’s attack commenced. Storms had scattered Lexington’s strike, and the overall results were even more disappointing than Yorktown’s. Most of Lexington’s dive-bombers missed their target altogether in the bad weather. Only the dive-bomber command element with four SBDs under Commander Ault found a target. All attacked Shokaku scoring another 1,000-pound bomb hit. Once again, all torpedo aircraft went after Shokaku, and once again her skipper was able to successfully dodge all 11 torpedoes aimed at her. Losses again were light with three fighters and one SBD being shot down. Another fighter and two SBDs, including Commander Ault’s, did not find their way back to Lexington. Of the 13 total Type 0 fighters assigned to CAP, two were shot down and one damaged by Wildcats. In return, the Japanese fighters accounted for two SBDs and three Wildcats.

The net result of the American strike was disappointing. Zuikaku, hidden by clouds, was unscathed. Damage to Shokaku, in the form of three 1,000-pound bomb hits, was severe, but she was in no danger of sinking. Casualties totaled 109 dead and another 114 wounded. While the fires aboard Shokaku were quickly extinguished, the damage left her unable to operate aircraft. She was ordered to depart the area at 30 knots under the escort of two destroyers.

On board Shokaku and Zuikaku, 18 Type 0 fighters, 33 Type 99 carrier bombers and 18 Type 97 carrier attack planes equipped with torpedoes were spotted in readiness. After the 0822hrs contact report, the entire strike was launched under command of Lieutenant-Commander Takahashi. Unlike American doctrine, the entire force departed at 0930hrs and proceeded in a single group under the control of Takahashi. Takagi followed his strike group south at 30 knots. Had he maintained his position, it would have been unlikely that any of the short-ranged American TBDs would have been able even to reach the area of the Japanese carrier force.

Awaiting the Japanese strike was TF-17 with its two carriers, five cruisers and seven destroyers. Fully expecting a Japanese morning attack, Fitch had done his best to mount a robust CAP. Eight Wildcats were already aloft supported by 18 SBDs on anti-torpedo plane duty. At 1055hrs, radars on Lexington and Yorktown reported a large group of aircraft at 68 miles on a bearing of 020 degrees. Immediately, nine more Wildcats and five additional SBDs were launched. The nine new Wildcats were ordered to proceed down the line of bearing to intercept the Japanese aircraft as far as possible from TF-17. The result of this outer air battle was not favorable for the Americans. The aircraft assigned to intercept the Japanese dive-bombers failed to do so until they had already commenced their dives and the Wildcats assigned to intercept the low-flying torpedo planes missed them in the clouds. Takahashi took his 33 dive-bombers to a position upwind from TF-17 while the 18 torpedo planes were ordered to conduct an immediate attack.

A somewhat indistinct but compelling photo of Lexington as seen from one of the attacking Japanese aircraft. Lexington is already burning and the number of splashes around the ship suggests this shot was taken during the dive-bombing attack. (US Naval Historical Center)

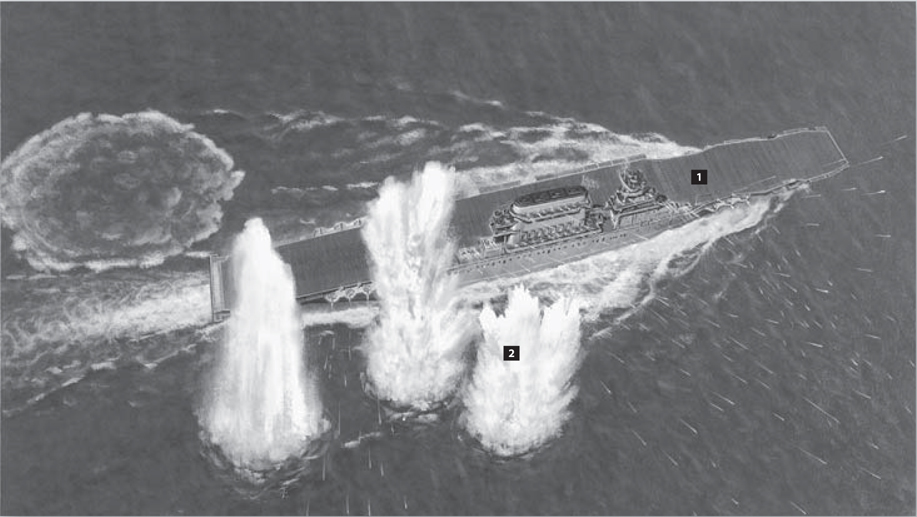

Only one of the MO Carrier Striking Force’s two carriers was attacked by American aircraft during the carrier battle of May 8, 1942. This scene shows Shokaku (1) in the midst of the attack by Yorktown’s dive-bombers. VS-5 has already conducted its attack with no result. Now it was the turn of VB-5. As Shokaku’s captain conducted evasive maneuvers at flank speed, the aircraft from VB-5 pressed their dives to 2,000ft before dropping their weapons. The first hit was scored at 1105hrs when a 1,000-pound bomb hit the flight deck on the port side forward. This created a massive fire that is already evident (2). Among the final group of VB-5 Dauntlesses was Lieutenant John Powers who was determined to score a hit on the frantically maneuvering Japanese carrier. During his dive, Powers’ aircraft was hit by 20mm fire from an attacking Type 0 fighter, which set the wing of the Dauntless on fire (3). Undeterred, Powers pressed his dive to under 1,000ft before dropping. His bomb scored a critical hit on the starboard side adjacent to the island creating massive fires on the flight and hangar decks. This hit ensured the Shokaku could no longer operate aircraft and would be unable to continue in the battle. Powers attempted to pull out of his dive at 200 feet but was unsuccessful and splashed near his intended target. For his undoubted determination and bravery, he was awarded the Medal of Honor posthumously.

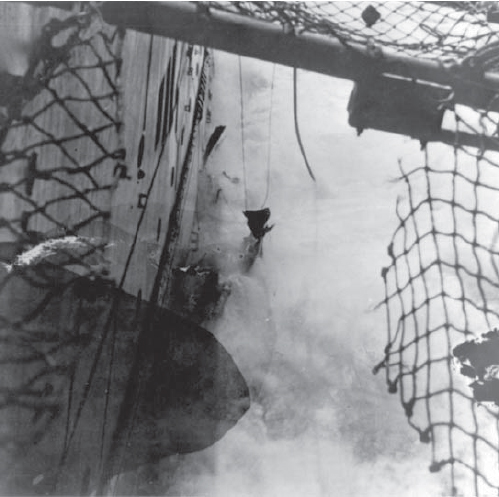

Unlike the damage caused by the two bombs that hit the ship, the two torpedoes that hit Lexington caused major structural damage. This view was taken on May 8 after the morning torpedo attack and shows the port side looking aft. Seen clearly is the damage caused by the torpedo that hit the ship amidships. Note the torn netting that was fitted on the flight deck level. (US Naval Historical Center)

Lexington during the torpedo bomber phase of the Japanese air attack on May 8. Note the anti-aircraft fire and the Type 97 carrier attack plane visible off the ship’s port side. (US Naval Historical Center)

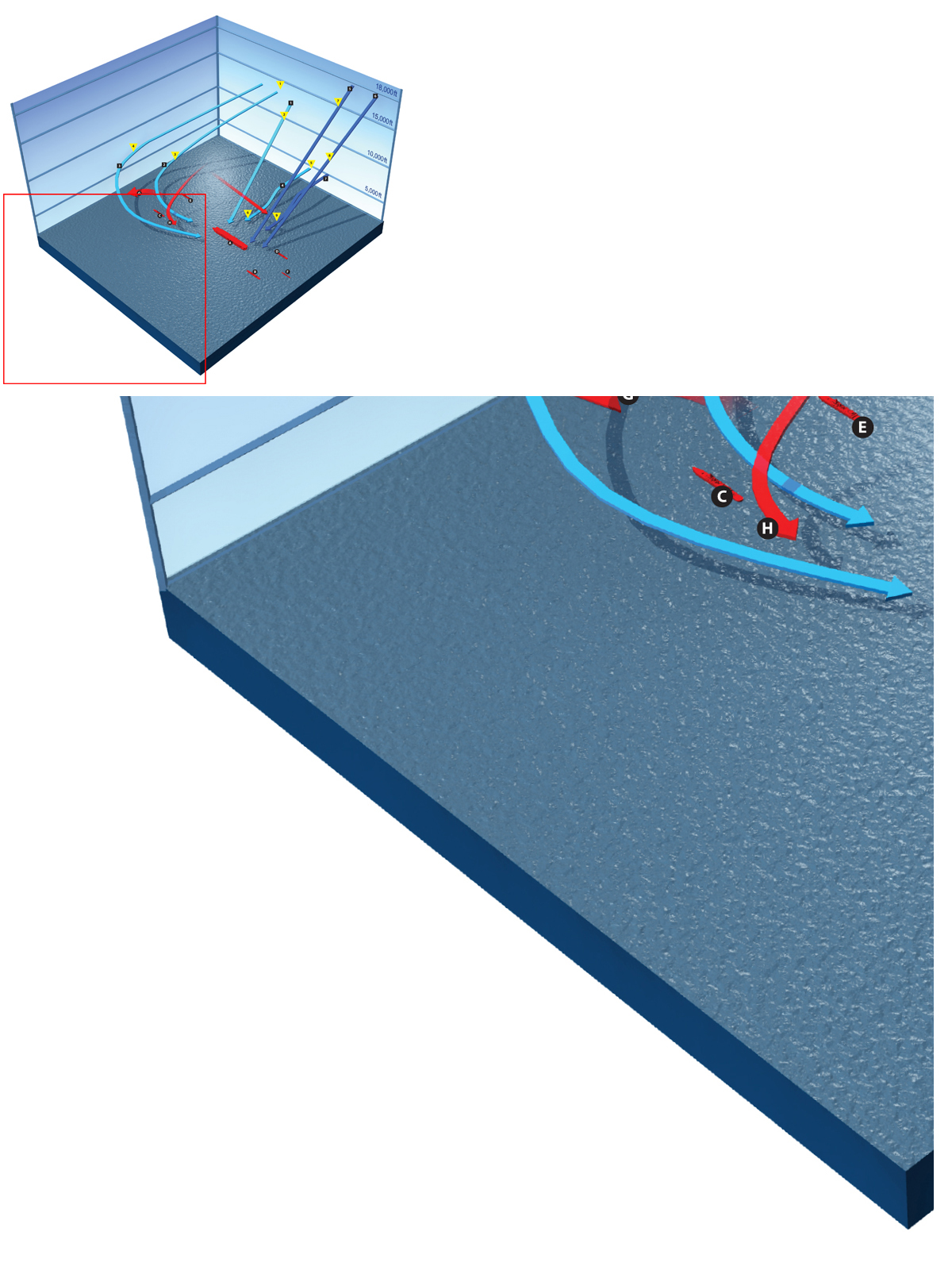

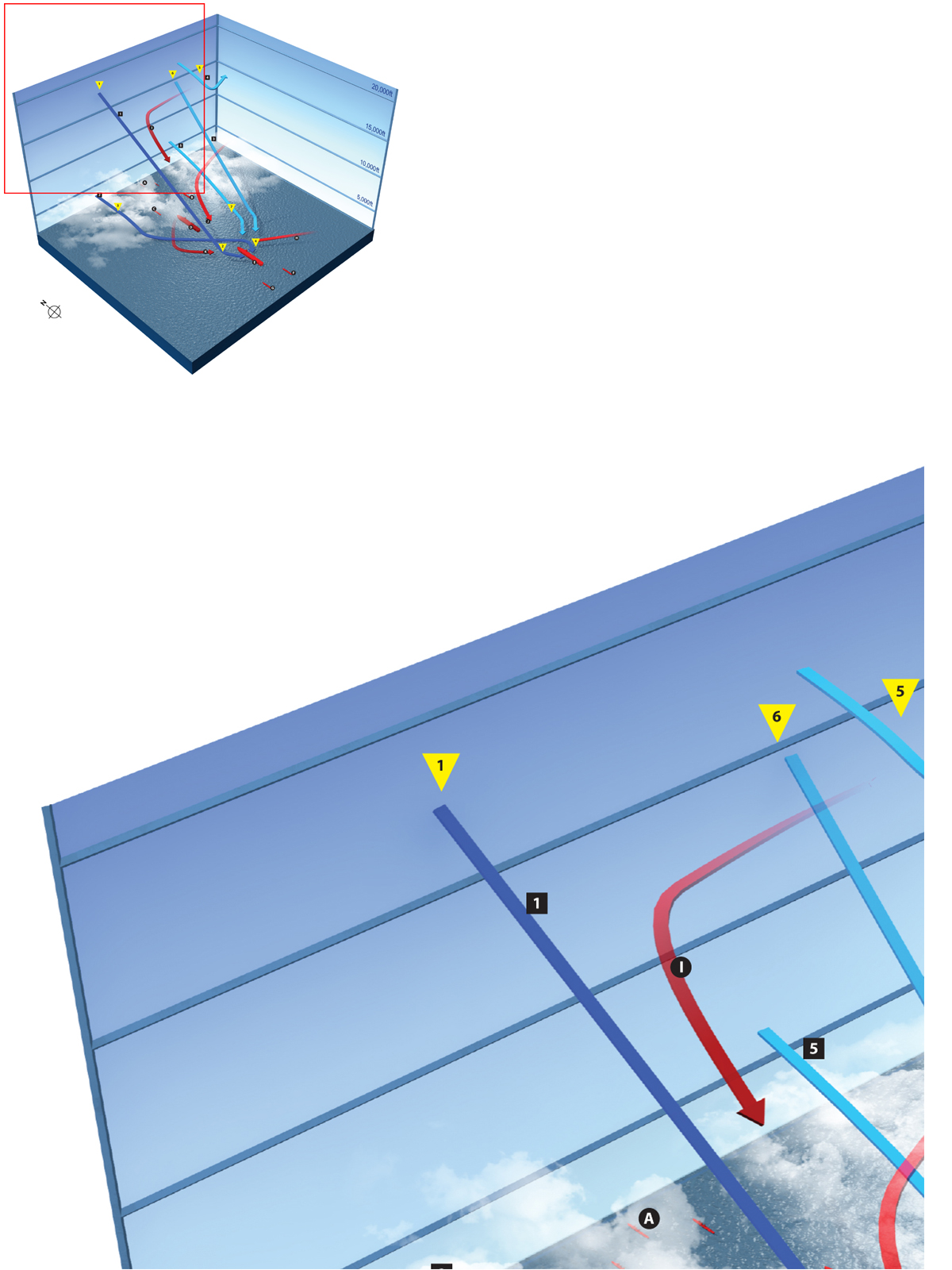

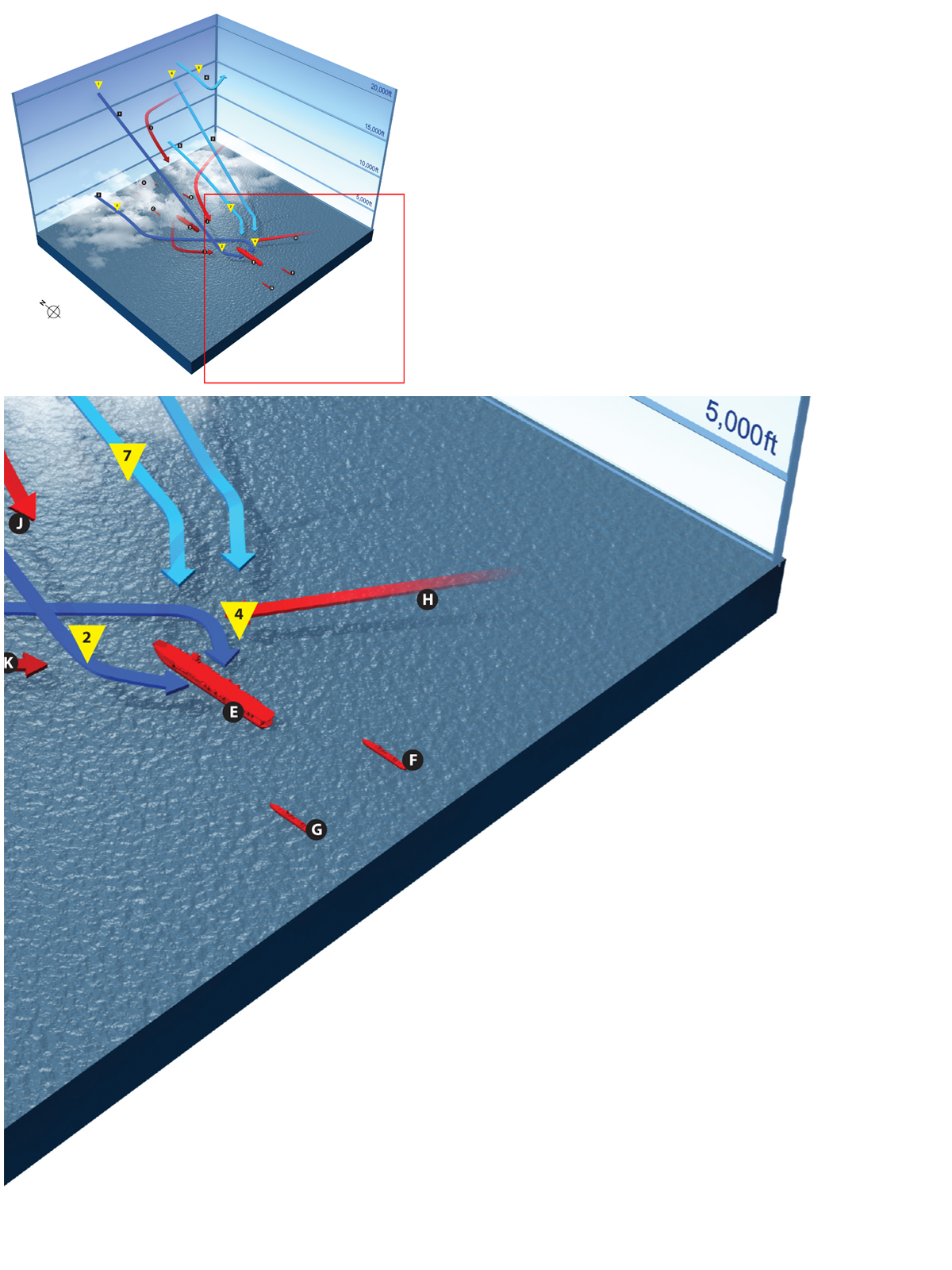

JAPANESE FORCES:

A Shokaku Fighter Unit (nine A6M Zero fighters)

B Zuikaku Fighter Unit (nine A6M Zero fighters)

C Shokaku Carrier Bomber Unit (19 D3A carrier bombers)

D Zuikaku Carrier Bomber Unit (14 D3A carrier bombers)

E Shokaku Carrier Attack Unit (ten B5N Carrier Attack Planes)

F Zuikaku Carrier Attack Unit (eight B5N Carrier Attack Planes)

AMERICAN FORCES:

1 Lexington

2 Yorktown

3 Minneapolis

4 New Orleans

5 Portland

6 Astoria

7 Chester

8 Phelps

9 Dewey

10 Morris

11 Anderson

12 Russell

13 Hammann

14 Aylwin

15 VF-2 CAP (four F4F))

16 VF-42 CAP (four F4F)

17 VF-2 CAP augmentation (five F4F)

18 VF-42 CAP augmentation (four F4F)

EVENTS

EVENTSYorktown Air Group attack

1. 1109hrs: The five VF-2 aircraft directed to climb to 10,000ft spot the Japanese dive-bomber group and give chase. The four VF-42 aircraft tasked to intercept the Japanese torpedo bombers never see them in the clouds.

2. 1112hrs: TF-17 changes course to 125 degrees. This places the Japanese torpedo aircraft off the carriers’ port sides

The Japanese torpedo Attacks

3. Fourteen B5Ns are ordered to attack Lexington and four to attack Yorktown. The main group, escorted by 15 A6Ms, approaches Lexington at 4,000ft and attempts to place her in an anvil attack. Ten rush straight at the ship and four from Zuikaku attempt to swing around and place Lexington in a pincer. VF-2 fighters dive on the torpedo planes and destroy one. The VS-5 SBDs are caught by six Zuikaku A6Ms and four are destroyed.

The thirteen remaining B5Ns headed toward the Lexington divide into four groups. Fifteen Lexington SBDs are deployed at 2,000ft altitude 3,000yds from Lexington. With only three A6Ms remaining to protect the B5Ns, the nine VS-2 SBDs on the port side are in a good position to intercept the torpedo planes. Two B5Ns are shot down, but 15 of 18 torpedo planes get through the American CAP

1118hrs: lookouts on Yorktown spot four B5Ns from Zuikaku off the port bow. Yorktown makes a starboard turn to keep her stern to the torpedo planes. One B5N launches torpedo and is shot down after launch.

1119hrs: the other three aircraft launch at 500yds but all miss along the Yorktown’s port side. Another B5N is shot down.

1118hrs: Lexington faces a pincer attack with three Zuikaku B5Ns and two Shokaku B5Ns curving around the port bow. The Japanese torpedo planes are at 150ft altitude trying to find gaps through the screen. If Captain Sherman turns Lexington into one group of aircraft to comb the tracks of their torpedoes, the other group will have a clear shot. Sherman decides to execute a port turn in order to present stern to the group of three Zuikaku aircraft. All three miss and the two Shokaku launch their torpedoes from the starboard side, but both miss astern Lexington.

Seven more B5Ns remain on Lexington’s port side. Sherman orders a hard turn to starboard to turn away from the threat. However, Lexington is slow to respond. The most northern group of two B5Ns veer off to attack the cruiser Minneapolis; both torpedoes miss. Only four more B5Ns remain to deal a serious blow to Lexington. The Japanese aircraft close to 700yds and then drop their weapons from 250ft. The first pair runs deep and passes under Lexington.

1120hrs: the first torpedo hit is taken on the forward port side. This is followed by another hit under the island.

The dive-bomb attacks on Lexington

4. 1121hrs: 19 Shokaku D3As dive from 14,000ft on Lexington. In the face of increasingly heavy antiaircraftLexington. In the face of increasingly heavy antiaircraft fire, the dive-bombers reach 1500ft and drop their weapons. Lexington is barraged by near misses, but only two bombs hit. Both cause minor damage. The last two dive-bombers abort their dives on Lexington and go for Yorktown; both miss. Of the 19 D3As, one is destroyed by anti-aircraft fire and one is shot down by fighters.

The dive-bomb attacks on Yorktown

5. 1124hrs: 14 Zuikaku dive-bombers begin their attack from 13,000ft.

1127hrs: A 250kg semi-armor-piercing bomb hits the center of the flight deck forward of the middle elevator. Because of the attacks by the two defending Wildcats, good ship-handling by Captain Buckmaster, and a difficult crosswind dive, this is the only hit scored. Several near misses also cause damage including a bomb amidships on the port side that opens fuel bunkers to the sea.

Lexington under attack from Type 99 carrier bombers on May 8. Of the 19 Shokaku dive-bombers that attacked the ship, only two scored hits and these inflicted minor damage. One of the dive-bombers can be seen above Lexington to the right after just having completed its attack. (US Naval Historical Center)

Of the 18 Type 97 carrier attack planes, 14 were assigned to attack Lexington with only four remaining to attack Yorktown. Despite the efforts of the defending Wildcats and the large numbers of SBDs conducting patrols against the slower torpedo planes, 15 of the 18 Type 97s survived the CAP to launch attacks. The four allocated to attack Yorktown all missed for the loss of two aircraft. With 14 Type 97s available to attack Lexington, and the limited maneuverability of the huge ship, the Japanese achieved much better results. With sufficient aircraft to mount an anvil attack, Captain Sherman could not avoid all of the nine torpedoes aimed at Lexington. After deftly avoiding the first five torpedoes launched from two groups attacking from each beam of the ship, the last group of four Type 97s had a clear shot. Two torpedoes ran deep under Lexington’s keel, but the final two scored hits on the port side. The first, at 1120hrs, hit forward and jammed the two elevators in the raised position. More importantly, it buckled the port aviation fuel tank and caused small cracks. In turn, this caused gasoline vapors to spread. The second hit was scored under the island near the firerooms. Three filled with water forcing three boilers to be shut down. Several fuel bunkers were opened to the sea, which created a large oil slick. The second hit caused a six to seven degree list, but movement of liquids inside the ship quickly corrected this.

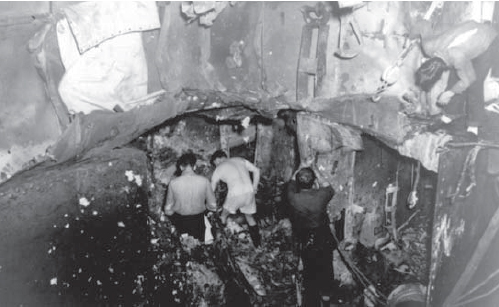

Yorktown suffered only a single direct bomb hit during the battle. Here sailors clear away debris from the third deck compartment that the bomb exploded in. Despite appearances, the damage was relatively light and the ship remained operational. (US Naval Historical Center)

This view is of Lexington’s forward port side 5in./25 gun gallery. The first bomb to hit the ship exploded here, destroying the gun and causing severe personnel casualties. (US Naval Historical Center)

Takahashi’s orders for the dive-bombers to take a position upwind placed them several minutes behind the torpedo attack. He ordered 19 dive-bombers from Shokaku to deal with Lexington with the balance of the dive-bombers from Zuikaku to attack Yorktown. Escorting Type 0 fighters were successful in protecting the carrier bombers from American fighter interception, so all 33 delivered attacks on their targets. Despite bravely pressing their attacks against increasingly heavy anti-aircraft fire, the results were very disappointing for the Japanese. Both American carriers were deluged in a series of near misses, but only a total of three bombs hit their targets. Against Lexington, two Shokaku dive-bombers scored direct hits. Both inflicted minor damage. The first hit the forward corner of the flight deck knocking out the forward 5in. sponson on the port side. The second hit the port side of the massive smoke stack causing little damage but inflicting casualties on nearby anti-aircraft gun crews. Two Type 99 carrier bombers were destroyed in the attack.

A Type 97 carrier attack plane going down in flames on May 8. During the actual attack on TF-17, an ineffectual American fighter interception and relatively ineffective antiaircraft fire translated into low losses for Japanese torpedo aircraft. However, overall losses of Japanese torpedo planes were catastrophic. (US Naval Historical Center)

Within minutes of the successful torpedo attack on Lexington (1), the ship was subjected to an intense dive-bombing attack from 19 Shokaku Type 99 carrier bombers. These dive-bombers began their attack at 14,000ft unmolested by defending American fighters. In turn, each Type 99 braved increasingly heavy anti-aircraft fire and dove to within 1,500ft of its target before dropping its weapons. Despite their determination, the Japanese were not rewarded for their efforts. Of 17 bombs dropped against Lexington, only two hit. Both of these caused only minor damage. The first hit the forward corner of the flight deck on the port side and knocked out the Number 6 5in. gun causing severe personnel casualties. The second bomb landed on the port side of the massive smokestack but caused little damage, though it did cause further personnel casualties among the crews manning nearby anti-aircraft weapons. This scene depicts the opening of the attack before either hit had been scored. Many near misses were scored, as seen in this view (2), and some of these caused damage to Lexington’s hull.

Against Yorktown, a combination of attacks by two defending Wildcats, good ship handling by Captain Buckmaster and a crosswind drop meant the 14 Zuikaku dive-bombers scored only a single hit. The single 550-pound semi-armor-piercing bomb hit the center of the flight deck forward of the middle elevator. It penetrated four decks before exploding where it killed the personnel of a repair party and caused structural damage. The resulting fire produced dense smoke that issued through the small hole left in the flight deck. The damage forced the temporary evacuation of three firerooms reducing speed to 25 knots. Several of the near misses were damaging. Another 550-pound bomb exploded amidships on the port side and was close enough to open several fuel bunkers to the sea creating a large oil slick.

The Japanese strike had not been as devastating as the Americans had expected. Yorktown’s crew had quickly put out the fires and the firerooms were re-manned bringing her speed up to 28 knots. Even Lexington, recipient of much greater damage, seemed to be battleworthy and in no danger of sinking. After the strike, Takahashi radioed back at 1125hrs that a Saratoga-class carrier had sunk as a result of nine torpedo hits and ten bomb hits. The Yorktown was damaged as a result of a claimed two torpedo hits and eight to ten bomb hits.

Despite the efforts of 20 Wildcats and 23 SBDs on CAP, Japanese losses were relatively light. The combined CAP, together with anti-aircraft fire accounted for an apparent total of five dive-bombers and eight torpedo planes. The cost to the Americans was three fighters and five SBDs. However, many Japanese aircraft were damaged resulting in the ditching of another seven aircraft en route to their carriers and another 12 were jettisoned owing to damage after they had landed. Returning VF-42 escorts from the Yorktown strike accounted for two additional Japanese aircraft, both noteworthy. One was the carrier attack plane that had spotted TF-17 and shadowed the American carriers for over an hour without having been spotted by the American CAP. The second was strike leader Takahashi, the leader of the Shokaku air group since Pearl Harbor.

Lexington viewed from the heavy cruiser Portland after the carrier has recovered her strike against the Japanese MO Carrier Striking Force. The ship remains operational despite taking two torpedo hits and two bomb hits from Japanese carrier aircraft. However, Lexington is clearly down by the bow, a result of the first torpedo hit. This view clearly shows the ship’s Coral Sea armament fit. In place of the 8in. gunhouses, 1.1in. quad mounts have been fitted and additional 20mm guns are also evident, including on a platform fitted at the base of the massive stack. (US Naval Historical Center)

Lexington’s crew abandoning ship on the afternoon of May 8. Every crewmember who got into the water is believed to have been saved. (US Naval Historical Center)

Both the Japanese and American air groups had been shattered by events of May 8. After both strikes had been recovered in the early afternoon, neither was in a position to resume the battle immediately. Yorktown’s strike returned at 1300hrs, but after recovery only 12 SBDs and eight TBDs were operational and only seven torpedoes remained in the Yorktown’s magazines for future strikes by VT-5. Lexington’s strike returned beginning at 1322hrs, but after an explosion at 1247hrs in the forward part of the ship, her condition looked uncertain. Given the uncertainty over the condition of Lexington, the condition of Yorktown’s air group (especially with regard to fighters) and the growing concern with TF-17’s fuel status since the loss of Neosho, Fletcher proposed at 1315hrs that TF-17 retire to the south. Fitch concurred at 1324hrs.

At this point, the battle of Coral Sea was effectively over, but the reckoning for the US Navy was not done. The torpedo damage to Lexington proved mortal. The first torpedo hit outboard of the aviation gasoline tanks had transmitted the shock of the blast to the tanks and created cracks in the seams allowing vapors to escape. By 1247hrs, these vapors had reached the motor generators in the ship’s internal communications room, which caused an explosion and fires in the forward part of the ship. Damage control parties could not control the spread of the fires and further massive explosions occurred at 1442hrs and 1525hrs. At 1707hrs, Captain Sherman decided to abandon ship before darkness made the rescue of the crew more difficult. Lexington was later scuttled by destroyer torpedoes and finally sank at 1952hrs.

The plight of the MO Carrier Striking Force was only marginally better. The damaged Shokaku had been escorted out of the area, and Zuikaku was ordered to recover all returning strike aircraft. Between 1310hrs and 1410hrs, 46 aircraft were recovered. Of these, 12 were pushed over the side and another seven ditched before they could land. At 1430hrs, a total of nine strike aircraft were operational aboard Zuikaku. Accordingly, Takagi informed Inoue that a second strike was impossible. The Carrier Striking Force headed north at 1500hrs to depart the battle area and to address the fuel situation that had become desperate, with some destroyers down to 20 percent of capacity.

The failure of the Carrier Striking Force to crush the American carriers meant the end of the MO Operation. On the morning of May 8, Inoue had ordered all forces not involved in the carrier battle to move northeast. That morning, search aircraft from Rabaul had also reported an Allied force of one battleship, two cruisers and four destroyers between the Louisiades and Port Moresby. Inoue’s plan to hit this force with land-based bombers from Rabaul was scratched when heavy rains grounded all aircraft at Rabaul. If having an intact Allied force with heavy units blocking his advance to Port Moresby was not bad enough, in the afternoon Inoue was informed of the results of the carrier battle. With Shokaku out of the battle and heavy aircraft losses that precluded a second strike, Inoue knew that the prospects for mounting an invasion of Port Moresby were over. At 1545hrs, he ordered all forces to head north; at 1620hrs he postponed the MO Operation and ordered the evacuation of the seaplane base at Deboyne Island.

The heavy cruiser Aoba played a frustrating role at the Coral Sea, first unsuccessfully screening Shoho and later being moved to screen the MO Carrier Striking Force. (Yamato Museum)

When Combined Fleet headquarters learned of Inoue’s postponement order, Yamamoto took immediate action. At 2200hrs, he ordered Inoue to continue to pursue the American forces and to complete their destruction. In response, Inoue ordered the reoccupation of the Deboyne Base and shifted the remainder of Goto’s most powerful remaining units, including his two remaining heavy cruisers and most of the 6th Destroyer Squadron, to join with the Carrier Striking Force. Thus reinforced, the MO Carrier Striking Force spent May 9 refueling, then re-entered the Coral Sea on May 10 to reopen the battle. Zuikaku’s operational aircraft had risen to a total of 45 – 24 fighters, 13 carrier bombers and eight carrier attack planes. By dawn on May 10, Takagi was some 340 miles southwest of Tulagi. From this position, he conducted a search but gained no contact. On May 11, the futility of continuing operations was obvious and the Carrier Striking Force moved around San Cristobal Island and headed north.

Like Takagi, Fletcher decided that the best course of action was to retire. MacArthur’s aircraft had already reported the northerly movement of the invasion convoy, so Fletcher could safely assume that the threat of invasion at Port Moresby was over. Following the sinking of Lexington, he could not risk losing a second of Nimitz’s precious carriers, which would have turned the battle into a strategic disaster for the US Navy. For the remainder of May 8, he moved south into the Coral Sea. Fearful of pursuit on May 9, he continued to retire at high speed. When Takagi’s remaining carrier attempted to regain contact on May 10, Fletcher was already safely out of the battle area. On May 15, TF-17 anchored at Tongatabu in the Tonga Islands, and from there the Yorktown proceeded to Pearl Harbor for repairs. On that same day, Halsey’s TF-16 with the carriers Enterprise and Hornet was spotted by a Type 97 flying boat approximately 450 miles east of Tulagi. These final moves in the battle of Coral Sea were actually the prelude to the battle of Midway, now less than three weeks away.

Not surprisingly, Japanese plans for the ambitious MO Operation proved fragile. Inoue had barely enough forces assigned to him to accomplish his mission, and those that he did have were primarily second-rate units. After the run of successes for the last five months, “victory disease” was alive and well in the Navy General Staff and the Combined Fleet. Both continued to count on a passive enemy who would play his predicted role while an intricate Japanese operation unfolded. Unlike in the first few months of the war when the Japanese had carefully orchestrated their moves to take place under conditions of local air superiority, this was not realistically achievable for the MO Operation. Instead of facing only meager Dutch, British or American land-based air forces where only minimal air protection had sufficed, in May 1942 the IJN planned to conduct a major invasion in the face of an American carrier force backed by large land-based air forces. It was not a formula for success.

Nevertheless, in spite of the fragility of the plans for MO, it did contain the seeds of success, if not against Port Moresby, then against the American carrier force. To Yamamoto, the latter was arguably more important than the former. When the MO Carrier Striking Force rounded the Solomon Islands, it was in a very favorable tactical position to ambush Fletcher’s unsuspecting carriers. Here the timidity of Takagi and Hara threw away the best Japanese hope for success. For two key days leading up to the battle’s climax, they did not conduct a general search for the American carriers, not wanting to reveal their position. Though the coordination between Japanese land-based naval air forces and their carriers was far better than the coordination between American land-based aviation and carrier forces, it was not good enough to allow Takagi to play such a passive role. On May 6 and again on May 7, the Japanese threw away a chance to launch a devastating blow against Fletcher’s carriers. On May 7 in particular, the Americans were very fortunate that Japanese reconnaissance efforts were so unbelievably faulty. Even during the climactic battle on May 8, the IJN’s aviators had the best of the exchange owing in no large measure to superior doctrine and coordination. Even after the exchange, Takagi should have realized that the true strategic prize at hand was not Port Moresby, but the American carriers. With this knowledge, he should have relentlessly pursued the second damaged American carrier, as Yamamoto reminded him late on May 8. By any measure, the battle of the Coral Sea was a series of lost opportunities for the Japanese.

For the US Navy, the battle was a close-run affair. When Nimitz saw an opportunity to engage a portion of the Kido Butai on near equal terms, he aggressively seized it. Charged to execute Nimitz’s order, Fletcher became fixated on the Japanese forces approaching from his northwest, which included, according to the intelligence he was provided, the Japanese carrier forces. Meanwhile, Fletcher ignored his eastern flank. After paying no price for this neglect on May 6, he was fortunate that the exchange on May 7 against secondary targets went his way and did not bring a full Japanese carrier strike on his force. After taking the brunt of the exchange on May 8, Fletcher was unfortunate that a material defect caused the destruction of Lexington. His withdrawal on May 8 with his remaining carrier was undoubtedly the correct decision, as was so profoundly evidenced by Yorktown’s pivotal role at Midway a month later.

A burned-out B5N2 Type 97 carrier attack plane on a reef somewhere in the South Pacific after the battle of the Coral Sea. The single white fuselage band indicates that this is an aircraft from Shokaku’s air group. Losses for Carrier Division 5 were heavy during the battle, especially in carrier attack planes. Of the 39 Type 97s available on May 6, only eight remained operational on May 10. (US Naval Historical Center)

Both sides paid a high price in the first carrier battle of the Pacific War. The invasion of Port Moresby had been turned away, but the Japanese did add Tulagi to their list of conquests. Losses to the IJN had been high, in fact more severe than any battle to date in the war. The light carrier Shoho was sunk, the largest ship lost thus far in the war. In addition, a destroyer and several minor ships were lost in the American carrier raid on Tulagi. Most importantly, the bomb hits on Shokaku kept her in the shipyard until July 1942. Carrier aircraft losses were very severe. Exact numbers are difficult to ascertain, but if sources stating that the total number of aircraft remaining (in all conditions) on Zuikaku on the evening of May 8 are accurate at 52, then Carrier Division 5 had lost 69 aircraft since May 6. Combined with the loss of Shoho’s entire air group (18 aircraft), at least 87 total carrier aircraft were lost. The heavy aircraft losses crippled Zuikaku’s air group and meant that she would also be out of action for several months. IJN personnel deaths totaled 1,074.