MICHEL-EUGÈNE CHEVREUL, COLOR, AND THE DANGERS OF EXCESSIVE VARIETY |

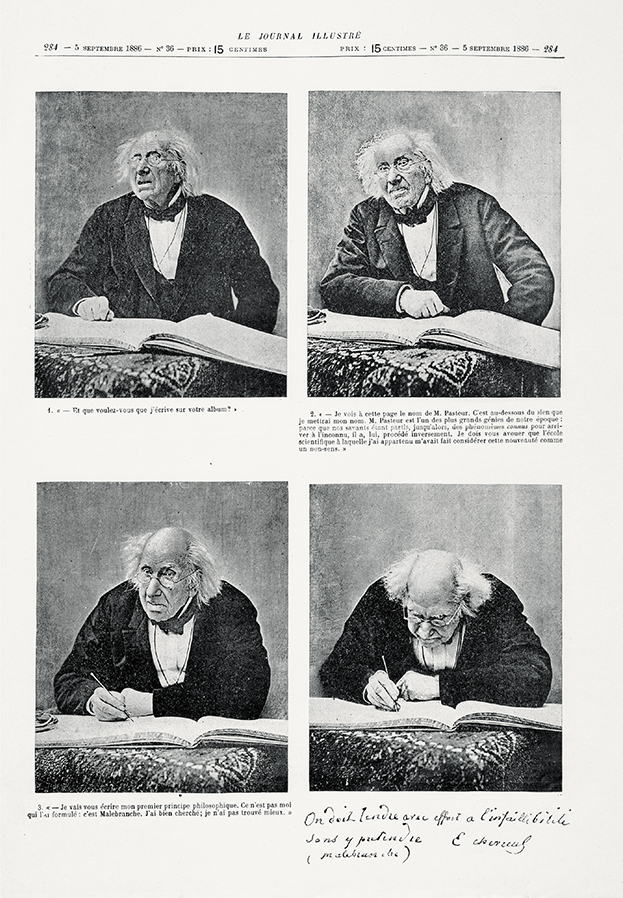

In the final decades of the nineteenth century, Michel-Eugène Chevreul was certainly the best-known chemist in France, possibly even in the world. In addition to having received the usual honors one might expect for a scientist of his training, expertise, and accomplishment, such as being elected to the Académie des sciences (1826) and admitted into the Légion d’honneur (1844), he had the privilege of having his likeness exhibited at the famed Parisian wax museum, the Musée Grévin, and appearing in the Panorama le “Tout-Paris,” a major attraction at the 1889 Universal Exposition in Paris.1 In 1886, Chevreul was interviewed by the Parisian photographer Nadar, assisted by his son Paul (fig. 7).2 Dubbed the “first photographic interview,” the record of this meeting, published in Le Journal illustré, contributed greatly to the men’s fame. French, British, German, and American newspapers ran articles focusing on the chemist, his work, and, most of all, his extraordinary longevity.

FIGURE 7

Félix Nadar, four photographic portraits of Michel-Eugène Chevreul, with handwritten note by Chevreul, in Le Journal illustré, September 5, 1886. Département des Estampes et de la photographie, Bibliothèque nationale de France, Paris.

For, indeed, Chevreul became famous for reasons having nothing to do with chemistry. Born in 1786, he died in his 103rd year, in 1889. At a time when the average life expectancy was around forty-four, Chevreul’s hundredth birthday received official national attention: two days of public celebrations, including a lavish banquet at the Hotel de Ville and torchlit procession on the grand boulevards of Paris.3 News of the chemist’s enduring health and optimism sounded a reassuring note during a time of intense political strife, soon to be intensified by the hundredth anniversary of the French Revolution. “He used to drive daily to watch the progress made in the erection of the lofty Eiffel tower, and witnessed the hoisting of the national flag on the summit when it was completed,” one journal noted shortly after his death.4

Adding to the strange contours of his celebrity, Chevreul’s masterwork, De la Loi du contraste simultané des couleurs, first published in 1839, was not a work of chemistry at all but rather pertained to the physiology and psychology of color perception. Indeed, overshadowing his pioneering work in the then-burgeoning field of organic chemistry, Chevreul earned his greatest public recognition for codifying the law of the simultaneous contrast of color, which explains the apparent modifications of hue, value, and saturation that result from the juxtaposition of two or more colors, and his development of a system for the scientific identification and classification of colors. The paradoxical nature of his fame was not lost on the chemist. Some fourteen years after the publication of De la Loi du contraste simultané des couleurs, he reflected that many who had praised him for his work on color had probably never read the book: “If we had told them that it was physiological and psychological, that it contains an experimental aesthetics of the visual arts [une esthétique expérimentale des arts qui ressortent de la vue], . . . these people would most probably have abstained from praising my work and would have, if not said, then thought that the time I devoted to these subjects would have been better spent working on chemistry!”5 These concerns were not entirely unjustified, judging from the criticisms—and silences—that appear in tributes and biographies published after Chevreul’s death.6

Still, that Chevreul had so many admirers during his lifetime shows that color was an important matter of consideration in the mid-nineteenth century, not just for a scientist like himself, but for a broad range of economic, social, and cultural actors. As we shall see, new technologies, media, and goods had all contributed to making bright and varied colors a central aspect of nineteenth-century urban life, and it is hardly surprising that the same spirit of scientific reform that animated so many other branches of human activity during this time would also leave an imprint on matters of style and the industrial arts in particular. Indeed, while most art historians writing on Chevreul have focused on how his ideas influenced avant-garde artists—from Eugène Delacroix to Robert and Sonia Delaunay—the chemist was clearly far more concerned with artisanal and industrial applications: tapestries, carpets, mosaics, stained-glass windows, calico and letterpress printing, wallpaper design, map making, flower gardens, and, of course, fashion and interior decoration.7 And it was among those involved in these trades—and tastemakers writing on fashion and interior decoration—that Chevreul’s theories were most widely diffused and arguably best known.

That is not to say that the audience of industrial artists Chevreul addressed in his books and lectures was uniformly won over by his ideas. Looking at the reception of the chemist’s principles of color harmony and his system for identifying and classifying colors, this chapter argues that, when it came to the practical application of his ideas, the famed centenarian lived both too long and not nearly long enough. For a variety of reasons, notably the emergence of new synthetic dyes starting in the late 1850s, the type of standardization and quantification that Chevreul promoted through his color wheels was never successfully employed in industry. Indeed, while producers of dyes and textiles willingly recognized the advantage of the chemist’s system, for most of the century they proved far more interested in providing consumers with a cornucopia of goods in an ever-widening array of styles and colors.

Chevreul’s inability to contain and control the colors of the marketplace is a powerful reminder of the limitations of expert knowledge and what can be learned from tales of scientific and technological failure. Colors emerging from the expanding synthetic dye industry refused to be quantified and ordered, despite Chevreul’s and his supporters’ best attempts to do so. The system the chemist devised for identifying and classifying colors, eventually popularized in the form of color wheels, proved difficult to construct and impossible to implement. Quickly relegated to the realm of scientific curio, Chevreul’s failed effort to regulate color thus sheds a unique light on the opposite reality of unrestrained chromatic novelty and variety that characterized the era.

At the same time, however, the quick proliferation of synthetic dyes provided the perfect context for the diffusion of the chemist’s principles of color harmony, derived from the law of the simultaneous contrast of color, which tastemakers presented to their readers as an unwavering touchstone in a world of increasing chromatic confusion. For those worried about this new state of chromatic cacophony, Chevreul’s principles of color harmony provided the perfect antidote—certain color combinations, he explained, were clearly superior to others. Thus, what follows is only partially a story of scientific failure. Devised in the 1830s, the chemist’s theories became newly relevant, offering guidance in the new aesthetic environment that took root in the second half of the century.

Tastemakers disseminated Chevreul’s ideas in books and magazines, but not without contributing their own interpretations to the new science of color harmony. Their ambivalent reception of Chevreul’s research suggests that the chemist’s understanding of color as a purely abstract and optical property failed to completely satisfy the public. In particular, the notion that colors possessed emotional and symbolic meanings still held widespread appeal among tastemakers. In the end, no consensus was achieved about the appropriate selection, juxtaposition, and meaning of colors in fashion and interior decoration. Chevreul’s ideas serve, therefore, less as a measure of nineteenth-century French taste than of cultural elites’ pained responses to the unrestrained variety of colors and styles that emerged with industrialization and the expansion of consumer culture.

Chevreul at the Manufacture des Gobelins: The Origins of the Law of the Simultaneous Contrast of Color

Chevreul became the director of the dyeworks of the national tapestry workshop, then known as the Manufacture royale des Gobelins, in 1824. Located in what is now the thirteenth arrondissement, in Paris’s southeast quarter, the workshop began its existence as a scarlet dyeing shop in the fifteenth century. Eventually converted into a tapestry workshop, the establishment was taken over by the French crown in 1662. For many years, it supplied royal residences with magnificent furnishings of all kinds, eventually specializing exclusively in tapestries. In fact, the term Gobelin is often used generically to denote fancy tapestries of all kinds, especially imitations of those produced by the French manufacturer during its heyday in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries.

In the early nineteenth century, large reproductions of paintings, including woven portraits and scenes depicting important historical events, remained very much in favor at the Gobelins, despite mounting criticism from decorative art experts, who argued that tapestry would fare much better were it not confined to imitating the effects of painting. Chevreul tried to stay out of this quarrel about the nature and look of tapestry that was slowly mounting all around him.8 Indeed, as he routinely pointed out, as director of the dyeworks he had very limited influence over the final appearance of Gobelin tapestries: “Foreign to the choice of models and craft of tapestry making, my functions are strictly limited to dyeing wools and silks to match as closely as possible the samples that I receive from the Administration.”9

Chevreul’s previous work on dyes and training at the Muséum national d’histoire naturelle under one of the country’s premier chemists, Nicolas Vauquelin, prepared him well for his position at the Gobelins. Applying the same methods of systematic testing and observation that elevated him to the top of the nascent field of organic chemistry, he quickly set about finding ways of improving the appearance and solidity of dyes—their degree of resistance to light, air, and other environmental factors, also known as fastness. As part of this work, he began analyzing black wools produced at the Gobelins, whose lack of intensity had apparently long troubled the shop’s workers. After comparing the Gobelins’s product with black wools from other dyeworks, he concluded that the problem lay not, in fact, with the dye but rather with the improper juxtaposition of colors in the tapestries—this was the origin of the law of the simultaneous contrast of colors. Dark colors, blues and violets in particular, he observed, seemed to cast a yellowish shadow onto the black surfaces in the tapestries, making them appear paler than they actually were. This modification, Chevreul furthermore established, was not chemical or physical but rather physiological and psychological in nature. In fact, to refer to a modification was only a “manner of speaking,” he emphasized. “It is really only applied to the modification that takes place before us” or, as he put it elsewhere, “inside of us.”10

Chevreul was not the first to notice phenomena of color contrast. However, whereas earlier experts generally attributed the apparent modification of hue or tone to optical fatigue or distress, Chevreul asserted that the illusion was a feature of normal human vision. When two colors are juxtaposed, he explained, the eye naturally perceives them as more different than they actually are. In the case of two complementary colors, such as red and green, for instance, the red surface seems to cast a green shadow onto the already green surface next to it, and vice versa. This has the effect of increasing the colors’ vividness. Conversely, when two similar colors are juxtaposed, they can sometimes seem dull or muddied. For example, a red surface placed next to an orange one will appear more violet, and the orange surface more yellow, than if the two surfaces were considered separately.

“This work is too remote from the science which has occupied the greatest part of my life, too many subjects differing in appearance are treated of, for me not to indicate to the reader the cause which induced me to undertake it,” Chevreul began the preface to De la Loi du contraste simultané des couleurs.11 Indeed, the matters of visual perception he addressed in this book lay far outside the realm of issues normally investigated by chemists. Still, that the problem he set out to resolve turned out to be physiological and psychological in origin greatly helped in diffusing his ideas. The law of the simultaneous contrast of color was not derived from complicated theories of light, nor did its demonstration depend on chemical experiments that could only be conducted in a laboratory. Rather, based on simple manipulation and observation, the phenomena Chevreul described were of immediate relevance and visible to everyone, not only to scientists but also designers and consumers of all types of colorful goods.12 Thus, while Chevreul’s research can certainly be situated within the context of eighteenth- and early nineteenth-century scientists’ elucidation of phenomena of subjective vision, as analyzed by Jonathan Crary, it also shows how the study of optical illusions had real consequences in day-to-day commercial and aesthetic matters.13 Indeed, as evidenced by the numerous practical applications addressed in De la Loi du contraste simultané des couleurs, from fashion and gardening to wallpaper and map making, there remained a fundamental continuity of interest and experience between the chemist’s law and the everyday visual experiences of producers and consumers of colorful goods.

This continuity of interest and experience is important when considering the scope and impact of Chevreul’s color theory. For example, it is worth emphasizing that the chemist never dedicated much energy to elucidating the psychological and physiological causes of contrast effects. He addressed the topic only briefly in De la Loi du contraste simultané des couleurs. “Whenever the eye sees two differently colored objects simultaneously,” he noted simply, “the analogous character of the sensation of the two colors undergoes such a diminution, that the difference existing between them is rendered proportionably more sensible in the simultaneous impression of these two colors upon the retina.”14 Twenty-five years later, Chevreul remained just as unforthcoming. Looking back at what he had written on the topic, he noted, “In these publications, I deliberately abstained from advancing what I felt would be a more or less questionable explanation of these phenomena.”15 The how and what of color contrast always mattered far more to Chevreul than the physiological and psychological why.

Showing how humans often perceive colors incorrectly, and this in a completely routine and predictable manner, Chevreul’s theories promised to limit waste in the factory and help resolve disagreements between producers and consumers of colorful goods. Before returning the latest delivery of black silks to its manufacturer in Lyon, the well-informed department store manager could now ensure that the fabric did not merely appear to be faded on account of the navy or purple fabric placed next to it. Even so, the economic dimensions of Chevreul’s theories do not exhaust their meaning. Addressed to producers and consumers of colorful goods alike, the chemist’s law of the simultaneous contrast of color and his system for identifying and classifying colors, to which I shall now turn, also raised new and challenging questions about the nature of visual experience, representation, and their relationship to one another. How does one represent a color on its own terms, as it were, divested from line and form? What is the relationship between cognitive and visual abstractions? And, finally, what, if anything, do these colors mean? These questions, it should be noted, arose not in response to Chevreul’s unveiling of the inherently subjective and unreliable nature of human vision, but through the practical process of making sense of the colorful impressions that industry produced and consumers craved. The chemist reassured his readers that the true local color of an object could always be determined and its beauty could always be improved through the skillful harnessing of contrast effects. Indeed, as he saw it, the uncertainties of color perception paled in comparison to those of color production and the marketplace. It is hardly surprising, therefore, that the optical devices he created aimed not only to produce new knowledge about visual perception but also to gain control over the production and consumption of colorful goods that increasingly shaped the look and feel of everyday life.

Publishing the Book and Constructing the Wheel

Chevreul gave his first lecture on the simultaneous contrast of colors before the Académie des sciences in 1828. He then spent the next seven years systematically testing his ideas and putting them in writing. Publishers were not immediately forthcoming, however, for as the chemist explained, “the condition which I set that the price should not be too dear, notwithstanding the expense occasioned by numerous colored plates, was an obstacle in finding a publisher.”16 De la Loi du contraste simultané des couleurs was eventually published, four years later than expected, by the firm of Paris-based editor Pitois-Levrault. The edition included a separate atlas for images, which counted forty plates, many of them colored by hand.17

The images are quite striking. Indeed, visual evidence suggests that they had far more influence on artists’ understanding of Chevreul’s theories than anything the chemist may have written or said (figs. 8 and 9).18 Among the images, however, there is one that remained conspicuously colorless: the diagram representing his system for identifying and classifying colors (fig. 10). The black-and-white line drawing was a poor substitute for the carefully graduated color scale Chevreul had envisioned and thanks to which he hoped to revolutionize how not only scientists described colors but also painters, printers, decorators, and “all artists who can apply the law of simultaneous contrast.”19 Indeed, while the idea of replacing imprecise color names with a standardized color metric was hardly new, few other systems for identifying and classifying colors had the same interdisciplinary ambitions.

FIGURE 8

Michel-Eugène Chevreul, “Four Disks: Red, Green, Orange, Blue (pl. 2),” in De la Loi du contraste simultané des couleurs: Atlas (Paris: Pitois-Levrault, 1839). Réserve des livres rares, Bibliothèque nationale de France, Paris.

FIGURE 9

Michel-Eugène Chevreul, “Assortment of Simple and Secondary Artists’ Colors with White, Black, and Gray (pl. 5-6-7),” in De la Loi du contraste simultané des couleurs: Atlas (Paris: Pitois-Levrault, 1839). Réserve des livres rares, Bibliothèque nationale de France, Paris.

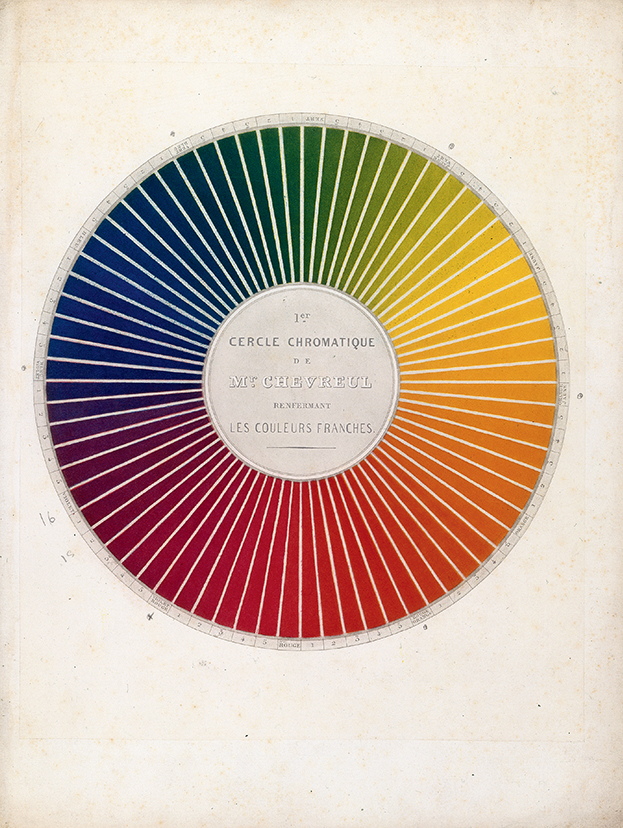

Popularized in the form of color wheels, Chevreul’s system was originally designed as a three-dimensional half sphere representing 14,400 colors, organized by hue (nuance) and tone (ton).20 The basic hue types include primary colors (blue, yellow, and red), secondary colors (violet, orange, and green), and six more admixtures. Each of these twelve segments is divided into six segments, for a total of seventy-two segments. To represent tonal variation, Chevreul divided these seventy-two segments into twenty equal parts, with the purest color falling somewhere along the radius (depending on its inherent tonal value), lightening colors going to white toward the center and darkening colors going to black toward the circumference. Finally, Chevreul imagined each of these 14,400 colors progressively darkened by the addition of black in increments of one-tenth. These darkened colors, also called broken colors, appear in the raised hemisphere above the circular base, the vertical axis representing pure black with no color and the horizontal axis representing pure unbroken colors.

The chemical revolution of the late eighteenth century, associated with Antoine Lavoisier, involved the transformation of chemistry from a science of qualities, principles, and sensations into a science of precise measurement.21 Following in the same path, Chevreul presented his system of color wheels as a way to move toward the precise measurement of color. Hue and tone received quantitative values, replacing the traditional heritage of names containing mythological, geographical, biographical, or, indeed, chemical references. The color known by the name émeraude (emerald green), for example, acquired the less poetic moniker 2 vert 11 ton. Broken colors received slightly longer names. For instance, according to Chevreul, the classic “red trousers” worn by French soldiers were better described as 3 rouge 3/10 11 ton, with the fraction indicating the amount of black added to the color.22 Much like the thermometer, therefore, which transformed temperature from a medical concept and experiential reality into a quantifiable scientific fact, Chevreul’s system transformed color into something more narrowly defined and precisely knowable. Indeed, the goal of the system, he wrote, was “to render the language uniform, as we are in the habit of doing in the determination of temperature by the thermometer.”23

The fact that, unlike a thermometer, Chevreul’s system did not in reality measure anything, but merely allowed for visual comparison with arbitrarily defined visual reference points, could not have escaped the chemist.24 It is notable, therefore, that Chevreul also referred to colors as types, a word more commonly used in classification and nomenclature systems in the field of natural history.25 “The object of chemistry,” Chevreul noted, “is to reduce matter to special types, each of which is defined by a collection of properties that it alone possesses.”26 These chemical types, he further explained, were the equivalent of species in the animal and plant kingdom: “We call these types chemical species [espèces chimiques], and the science that defines them brings us to consider them as distinct beings, in much the same way different species from the plant and animal kingdoms, which we call individuals, appear to us.”27 In referring to colors as types, Chevreul therefore strategically linked his work on color to the modern scientific enterprise of identification and classification, which had so greatly contributed to the prestige of chemistry and natural history.28

Besides scientific taxonomy and nomenclature, Chevreul’s hemispheric construction also bears the influence of the day-to-day production at the Manufacture des Gobelins.29 Chevreul’s system allowed, for instance, for a disproportionate number of broken colors, probably because these were extensively used in Gobelin tapestries. Some scholars have suggested that this overrepresentation of broken hues is a consequence of Chevreul’s misunderstanding of the difference between chroma and value, to use the terminology of today. The term chroma designates variations in a given color’s purity or intensity, in other words, its saturation. Value, in contrast, refers to the variation in lightness and darkness. According to Chevreul’s scale of tonal variation, however, these two qualities are rendered indistinguishable. “The word tones of a color will be exclusively employed to designate the different modifications which that color, taken at its maximum intensity, is capable of receiving from the addition of White, which weakens its Tone, and Black, which deepens it,” he specified.30 In fact, if we accept Chevreul’s explanations of his system, several colors that appear in the raised hemisphere of broken colors are redundant.31

Initially, however, the idiosyncrasies of the system failed to draw much attention. Instead, a much more important barrier blocked Chevreul’s project of universally reforming the language of color: aside from the black-and-white illustration of the system (see fig. 10), Chevreul did not have a prototype of any kind—no hemisphere, wheel, or thermometer—to work with and show the public. Indeed, as manufacturer Paul Eymard recalled about the course Chevreul taught in Lyon in 1842 and 1843, the chemist’s construction “was still but a draft; the essential was missing: it was color that would make the system tangible, so to say. The clearest and most lucid explanation was not as valuable as a demonstration made effective by color.”32

FIGURE 10

Michel-Eugène Chevreul, “Hemispheric Chromatic Construction (pl. 39),” in De la Loi du contraste simultané des couleurs: Atlas (Paris: Pitois-Levrault, 1839). Réserve des livres rares, Bibliothèque nationale de France, Paris.

Chevreul’s presentation must have been quite compelling nonetheless. For records show that members of Lyon’s Chamber of Commerce and learned society were extremely optimistic about the advantages that the chemist’s system would bring to the production of silk textiles. By eliminating misunderstandings between dyers and their clients, the system promised to save producers time, materials, and expense. For instance, Jules Bourcier, a member of the city’s Société d’agriculture, d’histoire naturelle et des arts utiles, remarked, “This table would make unnecessary the many samples that are used today to explain the manufacturers’ wishes to dyers; it would prevent the numerous discussions and arguments, which are the inevitable consequence of miscommunications or misunderstandings; finally, it would allow for a great amount of care, which until now has been wasted, to finally be usefully applied to industry.”33 Swaths of colored fabric provided by the client were typically the only point of reference for dyers. To match the client’s sample, dyers had to determine not only the right dye and mordant but also their quantities, as well as the duration and temperature of the dye bath and a host of other practical considerations that affected the appearance of the finished product. This work, known as échantillonage, was considered the “dyer’s ultimate goal, the acme of his art.”34 It was also one of the more time-consuming steps in the dyeing process. With Chevreul’s system, clients would be able to select from a standardized palette, where each color was associated with a specific dyestuff and process, thus greatly reducing time, effort, and cost. Colors, in short, would no longer need to be custom-made for each client.

Indeed, scientists and manufacturers from Lyon were so convinced of the benefits of Chevreul’s system that they quickly decided to request from the Ministry of Commerce a series of color wheels designed according to the chemist’s specifications. The wheels, Chevreul insisted, should be made from porcelain, an inalterable material, so that they could serve as a permanent and universal standard for the identification of colors. What the members of Lyon’s business and scientific communities failed to realize—and Chevreul himself ignored—was that the construction of such a device was beyond the means of even the most reputed ceramics manufacturer in France, the Manufacture royale de Sèvres. After trying to produce a few samples, the Manufacture de Sèvres informed the Chamber of Commerce of Lyon that it would be unable to fill the order. The group renewed its request in 1855, thirteen years later, and was again turned down, because, according to the minister of commerce, “the assortment of colors that the Manufacture de Sèvres holds are too incomplete to allow for the creation of a scale according to a precise and rigorous system. To fill in the existing gaps, it would be necessary to embark upon investigations that would be long and most probably fruitless.”35

The story of Chevreul’s repeated, unsuccessful efforts to provide the industrial and scientific communities of Lyon with a system for the identification and classification of colors reveals the gulf that existed between what was theoretically imaginable and what was technologically feasible at the time. Indeed, as Chevreul later reminded the public in a lengthy memoir presented at the Académie des sciences in 1861, “[the hemispheric construction], as it was originally described, in my 1839 work De la Loi du contraste simultané des couleurs, was purely theoretical.”36 In reality, many industries already produced a greater number of colors than the 14,400 required for the construction of Chevreul’s system, as evidenced by the chemist’s last documented attempt to have color wheels made out of porcelain. In 1864, seemingly convinced that the Manufacture de Sèvres had given up too early on his project, Chevreul contacted the commander of engineering of the French military division stationed in Rome, inquiring whether it might be possible to make his color wheel from the materials available at the papal porcelain workshop. Tellingly, in his letter to the commander, Chevreul explained that although he needed only 14,400 colors of the 25,000 produced by the Vatican ceramics factory, it was still uncertain whether he would be able to find the colors he needed to construct his color wheel. “You see, commander, I need fewer [colors] than there are at the Vatican, but will I find all my types among the 25,000, that is the question.”37 With its 14,400 different colors, Chevreul’s system was the perfect symbol of chromatic variety. Then again, Chevreul’s variety was an ordered and systematic one—the sort of variety that could be contained within a series of perfectly symmetrical color wheels.

The first set of color wheels created according to Chevreul’s model was not made out of porcelain, as he would have liked, but out of wool, using the materials and labor available at the Gobelins. Executed by the dyeworks’ foreman, a certain Mr. Lebois, the first of what would be a series of ten color wheels was presented to the Académie des sciences in 1851 and displayed at the Great Exhibition held that same year in London. The wheel represented only the seventy pure colors (couleurs franches) of Chevreul’s system, those neither darkened by the addition of black nor lightened by white.38 The subsequent nine wheels, completed that same year or shortly thereafter, featured the same seventy-two colors progressively darkened by the addition of black (from one part black and nine parts color to nine parts black and one part color). The series was an unsatisfactory compromise in Chevreul’s eyes, as evidenced by his continued efforts to produce color wheels made of porcelain, but a hard-won compromise nonetheless. “The dyeing gave the operator [Lebois] great difficulty,” Eymard explained. “There were a great many experiments and much trial and error.”39 According to the master table created at the Gobelins in the 1770s, the manufacturer already produced at that time around 25,000 different colors.40 As in the case of ceramics, then, the creation of Chevreul’s color wheels involved much more than the selection of seventy-two or more colors from the Gobelins’ extensive inventory. It also entailed the creation of new colors, unknown to expert dyers of the Gobelins, not to mention run-of-the-mill dyers operating in France.

Chevreul’s hemispheric construction was not designed to identify and classify the colors already in use in a specific industry or set of industries but offered instead a palette made of largely imaginary standardized colors that belonged to no one in particular. In other words, the chemist imagined his hemispheric construction not as a construction at all but as an immaterial theoretical construct. De la Loi du contraste simultané des couleurs did not explain how and out of what materials his system should be constructed; it merely noted the importance of creating “invariable types of color,” whether “from the solar spectrum, from polarized light, from the Newtonian rings, or from colors developed in a constant manner by any method” then imitated “as faithfully as possible by means of colored materials, which we apply on the circular plane of the chromatic diagram.”41 There was, however, a great—and ultimately unbridgeable—gap between the infinite spectrum of colored light, Chevreul’s 14,400 established types, and the palettes available in industry (which, although richly varied, remained the more or less haphazard product of usage and tradition).

Eluding the Color Wheel

In order for Chevreul’s ideas to be diffused to a wider audience, it was essential that his color wheels be reproduced in print. This was accomplished for the first time by the engraver René H. Digeon in 1855, using an uncommon printing technique known as chromocalcographie, involving the superposition of four printings—blue, red, yellow, and black—obtained from steel plates.42 As in the case of the wool color wheels, the printing of Chevreul’s wheels was not an easy task (fig. 12). “This printer exhibited facsimiles and color prints that show an exhaustive study of the combination of tones and true understanding of the scale of colors. The skill with which he reproduced the chromatic circle of M. Chevreul indicates serious research,” noted the official jury report of the 1855 Universal Exposition in Paris, where Digeon received a first-class medal for his work.43

FIGURE 11

Color wheel showing the seventy-two “pure colors” (couleurs franches) of Chevreul’s system, 1864, similar to the one exhibited at the 1851 Great Exhibition in London. The sculpture depicts the famed chemist. Both currently in the dyeworks of Mobilier National, Paris.

FIGURE 12

Michel-Eugène Chevreul, “Color Wheel by Chevreul Featuring Pure Colors (couleurs franches),” in Cercles chromatiques de M. E. Chevreul, reproduits au moyen de la chromocalcographie, gravure et impression en taille douce combinées par R.-H. Digeon (Paris: Digeon, 1855). Réserve des livres rares, Bibliothèque nationale de France, Paris.

As time progressed, however, the extraordinary efforts expended to create these optical devices must have seemed increasingly foolhardy to Chevreul’s colleagues. Reflecting on the scientific contributions of his colleague, chemist Marcellin Berthelot suggested that Chevreul had likely turned to these theoretical pursuits as a result of not being able to reform the practical aspects of dyeing at the Gobelins: “This was when, in fact, began the long construction of the color wheels, which he presented to his visitors with somewhat naïve satisfaction and in which he worked to imprison the entire theory of natural colors.”44 Berthelot’s criticism was cutting but not entirely unjustified given the ultimate fate of Chevreul’s system.

The key phrase here is natural colors. Within a decade of their creation, Chevreul’s color wheels were made largely obsolete by the introduction of synthetic colors, for which the chemist was unable to find a match in his system. Chevreul’s color wheels were useful to industrialists, but only, Berthelot wrote, “up until the day when the discovery of artificial colors, prepared from coal tar and at first aniline, produced brilliant colors of an incomparable vividness and that escaped the color wheels.”45 Chevreul, he went on to explain, tried to salvage his color wheels by introducing a new variable, nitens, corresponding to brightness, “but this ill-defined indirection failed to save the system.”46 In other words, not long after completing the first set of color wheels, first in wool and then in print, Chevreul’s dream of creating a permanent and universal standard for the identification and classification of colors came to an unexpectedly disappointing end. The system would not survive the extraordinary development of the synthetic dye industry and the incomparable, uncontrollable variety of its colors.47

The story of mauve and other early synthetic dyes, which in retrospect revealed the folly of Chevreul’s plans to contain and control colors, has been recounted elsewhere but is worth briefly recalling here.48 Discovered in 1856 by English chemist William Henry Perkin, mauve was the first commercially successful dye produced from aniline, a derivative of coal tar. Violets, lilacs, and purples were already popular colors in women’s fashion.49 Mauve’s unusual glow and origins, however, immediately set it apart from other dyes commonly used at the time. Unlike existing dyestuffs, which were commonly derived from plants, insects, or lichen, mauve was a substance not found in nature. It was a wholly artificial synthetic product that had to be purposefully created by chemical reaction.50 Furthermore, unlike indigo, cochineal, logwood, safflower, and other natural dyes popular at the time, mauve was not an exotic product imported from a faraway land. For several years, it continued to be manufactured mainly in Europe, close to the silk, wool, and cotton mills, dyeworks, and printhouses, whose production was setting new records each year. Indeed, it is doubtful that Perkin would have been successful at marketing his new dye had it not been for the high level of economic activity and enthusiasm for innovation that characterized the European textile industry at the time.51

A mere three years after the discovery of mauve, French dyers Renard frères et Franc introduced another synthetic dye, produced by submitting to a different reactant the same coal-tar-derived aniline that yielded mauve. The end result was a new red color, known under the names fuchsin, aniline red, and magenta, the latter in honor of the blood-soaked fields of the Battle of Magenta, where French troops fought against the Austrians in 1859. “Never had the dye industry produced a more brilliant color and, from then on, all intellectual resources were put into finding different ways of obtaining analogous colors,” reported the assistant director of the Manufacture des Gobelins, Charles Decaux, visibly impressed by what he had seen at the 1862 International Exhibition in London.52 Chemists and dyers in France agreed that the pinkish-red color produced by fuchsin was unlike anything they had seen before, noting also how this new product wasted no time upsetting traditional trade patterns. “Who, indeed, would now dare to have cargoes of safflower shipped from India?” asked Le Teinturier universel. “This substance, which a couple of years ago had a considerable value, is destined to disappear from the European market as a result of the manufacturing of aniline red, that is to say, fuchsin.”53

While the palette of aniline colors expanded to include magnificent blues, greens, yellow, browns, and blacks, chemists set themselves the ambitious goal of producing synthetic versions of tried-and-true natural dyes. German chemists Carl Graebe and Carl Liebermann succeeded in this task in 1868 in the case of madder, a commonly used red dye. Known as alizarin, the product of Graebe’s and Liebermann’s research was successfully commercialized a few years later by Badische Anilin und Soda Fabrik (BASF) and Perkin. Indigo was first synthesized by Adolf Baeyer in 1877. It was not until 1890, however, that chemists developed a way of manufacturing synthetic indigo on an industrial scale.54

Meanwhile, starting in the 1860s, English and German dye manufacturers introduced a new generation of acid-based dyes, known as azo dyes, that could be applied to cotton much more easily than aniline dyes. From the myriad of possible coupling reactions, chemists found a good substitute for cochineal red, which they marketed starting in 1884 under the name Congo red, and a host of other valuable dyes.55 In short, as historians of technology and business have shown, the first decades of the synthetic dye industry were marked by an intense focus on product innovation. For centuries, there had been no more than fifteen to twenty commercially viabxsle dyestuffs. But from the late 1870s to the First World War, the number of tradable dyes increased by close to the same number each year, resulting in hundreds upon hundreds of new dyes.56

As with most nineteenth-century fashion trends, the taste for bright synthetic colors was first visible among members of the royal and imperial courts of Europe. In 1857, mauve appeared in the wardrobe of the trendsetting Empress Eugénie, attracting the attention of journalists worldwide.57 The color then quickly spread to the closets of royalty and the well-to-do across Europe. Mauve, magenta, and bleu de Lyon garments followed the same path. After this initial phase, however, during which aniline dyes were the preserve of wealthy fashionable women, prices quickly dropped. Fuchsin, for instance, which sold for 1,600 francs per kilogram when first introduced, dropped to 10 francs per kilogram in the 1890s.58 The shift from luxury to mass-market product was so dramatic, in fact, that several contemporary observers estimated that the synthetic dye industry constituted a prime example of modern industry’s accelerated expansion and capacity to raise living standards for all members of society. “The history of aniline dyes, which covers only twenty years, is rich in lessons of all kinds. It shows with striking examples how quick the development of a new industry can be today,” noted Alain Radau in La Revue des deux mondes.59

In short, the transition from natural dyes to synthetic ones heralded at once the democratization of earlier visual experiences and pleasures associated with color and the irruption of novel visual experiences—synthetic colors were brighter and more varied than ever before—on a wide social, economic, and cultural scale. The development of synthetic dyes and the chemical industries, in general, was an essential dimension of industrialization, whose well-known smoke stacks, dark satanic mills, and slums make it difficult to imagine the period in anything other than black, white, and many shades of gray. Yet, as the technological and business history of textile production makes clear, dyes took on new and increased importance as producers began redirecting production toward cost-conscious middle-class consumers. This was especially evident in the silk industry, where the production of fancy woven fabrics decreased in favor of plain silks dyed in eye-catching colors. Gradually, a new system of design emerged, in which color mattered more than other qualities of the fabric and styles multiplied and changed much more quickly than before.60

Tastemaking in the Age of Bariolage

Examining not only silks in Lyon but also calicoes in Mulhouse, wools in Lille and Roubaix, and ribbons in Saint-Étienne, economic historians writing on France’s particular path to industrialization have highlighted the importance of novelty and variety for the nation’s manufacturers. Instead of investing in machinery appropriate for standardized mass production, French manufacturers preferred to adopt less specialized technology that allowed for the frequent redesign and reorganization of production. Manufacturers producing small batches of colorful products thrived, constituting the model for French industrialization.61 The revolution in production that, across Europe, was increasing the quantity and variety of products accessible to consumers was, therefore, particularly pronounced in France, where technological systems favored the emergence of a fast-changing, novelty-driven consumer culture.

From a consumer’s perspective, this proliferation of colors and styles was clearly visible in magasins de nouveautés and larger department stores. One 1875 department store catalogue, for example, listed no fewer than fifty-two shades of silk fabrics, ranging from the workaday “pain brûlé” to the literary “Ophélia.”62 In his notes for his classic novel on the French department store, Au Bonheur des dames (1883), Émile Zola transcribed a long list of fabric color names, similar to the one appearing in the catalogue, noting also how “women are . . . dazzled by the abundance of merchandise . . . the variety and novelty of the designs. One sees ten different kinds, one can choose. Therein lies the success of the stores.”63 Indeed, throughout the novel, Zola drew special attention to the pleasurable cacophony of colors created by department store managers.

From distributors’ standpoint, managing these growing inventories of fashionable goods was not an easy task. Edmond Bourdain’s Manuel du commerce des tissus (1885) addressed everything a fabric-store owner or manager needed to know to run his business, from how to evaluate the quality of the merchandise received from suppliers to the organization and display of goods in the store. Stocking the rayon de fantaisie, that is, the section dedicated to the latest novelties, Bourdain emphasized, was particularly problematic “in light of the enormous depreciation all merchandise having spent only two years there suffer.”64 It was crucial to be prudent when ordering new materials. For unsold products, he warned, lost 25 percent of their value after one year, 50 percent after two years, and 75 percent after three. Color was of central importance in these matters of inventory management, as shoppers’ tastes in this area were particularly unpredictable. “The whims of fashion, which push clients incredibly quickly to become passionate about colors that they hated the day before and to abandon all of a sudden those that seemed to please them more, cause considerable prejudice to marchands de nouveautés.”65 Color, in sum, was a key aspect of the visual appeal of fabrics, garments, and fashion accessories sold in these stores. Novelty and variety were especially valued by the bourgeois shopper, for whom the ability of choose among “ten different kinds,” as Zola put it, came to represent a quintessentially modern pleasure.

Described by Bourdain as a challenging problem of inventory management, the rapid expansion of the industrial palette caused even greater consternation and worry among tastemakers. Indeed, the increased availability of fashionable goods, the widening gulf that separated the producers of these goods from the men and women who consumed them, and the substitution of a unified courtly style for divergent middle-class preferences were matters of grave concern according to fashion writers, decorative art experts, and other arbiters of public taste, starting with Chevreul himself. His masterwork, De la Loi du contraste simultané des couleurs, was prescriptive as well as descriptive. More than a mere scientific fact, the law of simultaneous contrast of color was also an aesthetic principle capable of improving design and taste—certain color combinations were clearly superior to others, the chemist asserted.

For fashion, interior decoration, and other nonimitative uses of color, the juxtaposition of complementary colors, Chevreul believed, almost always produced a visually pleasing effect. “This case is so advantageous to the associated colors,” he noted, “that the association is also satisfactory when the colors are not absolutely complementary.”66 In comparison, the combination of analogous colors, such as a rich reddish brown and purplish red, was much more likely to have a disagreeable effect, especially if the two colors were of a similar tone. Chevreul predicted that public taste, having assimilated these scientific principles of color combination, would no longer be subject to “enlist[ing] its suffrages by falling into the bizarre, or in wandering from the truth,” but would itself be transformed. Indeed, as he saw it, the soundness and utility of his principles of color harmony were absolutely undisputable. “We cannot . . . refuse to recognize the utility of such an examination for the authors of works to whom they are submitted, and for the public to which it is more particularly addressed,” he boasted. “A clear demonstration of what is laudable or censurable will form its taste,” he continued, explaining, more specifically, how “in teaching it to abandon its first impressions, [the public] will itself become capable of expressing a sound judgment.”67

Chevreul’s passages about the sense of pleasure derived from the spectacle of variety are highly revealing in this respect. “Whenever man seeks distraction from without,” he wrote, “whether the pleasures of meditation are unknown to him, or thought fatigues him for a time, he feels the necessity of seeing a variety of objects. In the first case, he goes in quest of excitement, in order to escape from ennui; in the second, he is desirous of diverting his thoughts, at least for a time, into another channel. In both cases, man flies monotony; a variety of external objects is what he desires. . . . It is to satisfy this want that various colors in objects please more than a single color. ”68 Here, Chevreul drew upon the long-standing philosophical tradition that associated aesthetic pleasure with the balancing of variety and unity, wherein the latter, finding unity amid a variety of impressions, was deemed the more lofty mental exercise.69 Indeed, in Chevreul’s view, while variety, asymmetry, and contrast always produced a lively effect, an overarching sense of unity was necessary for the eye to appreciate these diverse impressions. “If the principle of variety recommends itself because it is contrary to monotony,” Chevreul insisted, “it should be carefully restrained in its applications, because, even without falling into confusion, effects may be produced [that are] far less agreeable than if they had been more simple.”70 Variety, therefore, was only pleasurable up to a point, after which it degenerated into bariolage.

Although this term was coined in the seventeenth century, probably from the coupling of barré and riolé, two words meaning “striped,” the experience of bariolage described in nineteenth-century sources was a distinctly modern one.71 Synonymous with the multiple and jarring colors of the marketplace, bariolage pointed to the significance of variety as an economic principle, social condition, and aesthetic experience. The taste for color, Pierre de Lano believed, was a symptom of the feverishness and fundamental corruption of modern life—a tormented psychological state marked by the constant desire for more.72

Alongside de Lano’s description of the modern appetite for color, tastemakers’ responses to synthetic colors and, more generally, the modern experience of bariolage provide a window onto French elites’ anxiety concerning the aesthetic and social challenges posed by modernity. Indeed, as Leora Auslander has shown, it is best to avoid seeing etiquette and decorating books, furnishing guides, fashion magazines, and other forms of prescriptive literature as barometers of French taste, bourgeois or otherwise. Starting in the 1860s, an extraordinary number of people in France made a living commenting on matters of taste and style. Some wrote exclusively about fashion or interior decorating. Others wrote on both subjects, pointing to connections between décoration vivante, that is, the woman of the household, and décoration immobile, her surroundings. They were journalists, art critics, sociologists, bureaucrats, politicians, manufacturers, sometimes playing several roles at once. They had varied political and institutional affiliations and varying degrees of influence on government policy. More than their individuality, however, their ubiquity and their remarkably similar analyses of French taste are what make them significant. Production and consumption, they agreed, urgently needed to be reformed, not least through the widespread dissemination of Chevreul’s scientific law of color harmony.73

Contrary to the popular notion at the time that, while drawing could be taught, color was purely a matter of instinct, tastemakers promoted the idea that color, too, could and should be brought under rational and deliberate control. Writing in 1861, Emmeline Raymond, the director of La Mode illustrée, for example, decried “the insane bariolage of certain outfits” and “the orgy of colors” to which certain women had become addicted. Alas, despite Parisian women’s generally superior sense of style, evidence of chromatic confusion was seemingly everywhere, she complained.74 Circulating in different social circles, Charles Blanc, the director of the Bureau des Beaux-Arts during both the Second and, for a brief time again, Third Republics and founder of the prestigious Gazette des beaux-arts, agreed with Raymond that many women had a poor sense of color: “Every day, our promenades, streets, salons, theater lobbies are crisscrossed by women with clashing outfits. This one, all dressed in black, displays a pink flower on her bonnet, which in its isolation creates a spot, in much the same way a single source of light in a painting would only but pierce a whole. . . . We saw one woman of sparkling wit wear a scarlet waistcoat over a groseille des Alpes petticoat, creating by the combination of the two colors an optical scandal.”75 By using the terms spot (tache), pierce (percer), and optical scandal (scandal optique), Blanc sought to communicate the sense of disharmony and discomfort he experienced. Moreover, the reference to groseille des Alpes, a color term used almost exclusively to speak of fashion, highlighted the specifically feminine, frivolous, and commercial origin of the offense.

Following Chevreul, critics writing about the decorative arts complained most often and most forcefully about the absence of a general idea or style coordinating the disparate colors and textiles in a room. In L’Ornement polychrome (1869), Auguste Racinet, while generally advocating for the incorporation of more color in the decorative arts, stressed that in order “to create [an impression of] unity from the variety of juxtaposed colors, a dominant, assimilating hue is necessary.”76 A generation later, Henry Havard expressed a similar point of view in L’Art dans la maison (1884) and La Décoration (1892), where he advocated in favor of the importance of making all the elements in a room bow to a general decorative scheme. “If variety is necessary, unity in conception and ordering is no less indispensable; and this unity can only be produced on one condition, which is that the entire composition stems from a single starting point,” he noted, using virtually the same terms as Racinet.77

This same philosophy of aesthetic harmony was also visible in the writings of fashion experts. In another article addressing the subject of color, titled “La théorie des couleurs dans ses rapports avec la toilette,” Raymond discussed the importance of finding a balance between unity and variety, stating, “Indeed, without diversity, without change, there is no life; without unity, there is no whole, no totality, no conclusion.”78 Badly dressed women failed to create a unified impression. Similarly, Blanc discussed how variety—in the form of color contrasts, asymmetrical designs, accessories, and so on—always needed to be carefully dosed. “To the dignity of women’s dress,” he wrote, “is related everything that allows unity to triumph while at the same time livening it with small touches of variety.”79

In the context of increasing chromatic diversity and confusion, namely as a result of the development of synthetic dyes and the production of inexpensive colorful goods for the home, it is not surprising that Chevreul’s law of color harmony gained such a wide and diverse audience. Architect-decorator Édouard Guichard extolled the chemist’s law in his address to the Union centrale des beaux-arts appliqués à l’industrie on June 15, 1866. Gone were the days of uncertainty, he opined. Thanks to Chevreul, it was always possible to find a color of furnishings that would enhance a woman’s beauty, regardless of her hair and skin color, “because the harmony of colors is a sure science, gloriously applied by the great colorists both ancient and modern, learnedly studied, elaborated, and fixed by one of our illustrious contemporaries—I mean Mr. Chevreul.”80 Writing later in the century, Antonin Proust, president of the Union centrale des arts décoratifs from 1882 to 1889 and of the organizing committee of the 1889 Universal Exposition, expressed his wish that all artists learn Chevreul’s law of the simultaneous contrast of colors.81

Consumers, tastemakers agreed, could also find ample guidance in the law of the simultaneous contrast of colors. And yet, the diffusion of Chevreul’s ideas in prescriptive literature shows that the chemist was far from having a complete monopoly over how color was defined and understood, even within the limited sphere of tastemakers. Like Chevreul, Raymond suggested, among other things, that light-skinned women with blond hair should preferably wear blue (so as to highlight their predominantly “orange” complexion). However, to this suggestion, derived from the law of the simultaneous contrast of color, Raymond added the observation that every complexion and hair-color type corresponded to a personality type. Most women with fair skin and blond hair also had nervous temperaments, she contended. Given this, the blue garment complemented not only women’s hair and skin colors but their personalities as well.82

Citing Chevreul’s theory by name, Blanc likewise emphasized the aesthetic appeal of complementary colors. He highlighted, however, that “the eyes are not the only ones interested in the spectacle of assorted colors and harmonies or dissonances of an outfit; sentiment has its place, and as a wise woman once said, ‘It is still permissible to dream in a sky-blue hat; it is forbidden to cry in a pink one.’”83 In other words, by speaking only to the eyes, as Blanc put it, Chevreul’s principles of color harmony suppressed sentiment, symbolism, or other established standards of judgment and practices of signification. Color was not, therefore, a purely optical phenomenon but was also connected to morality, passion, and sentiment. “That is why,” Blanc stated, “women, ruled by sentiment, attach more importance to color.”84

While Raymond and Blanc tried to make room for personality and sentiment in Chevreul’s color theory, other tastemakers, such as Viennese physiologist Ernst Brücke (whose book on color was immediately translated into French), contested the very notion that complementary colors were always a flattering combination, thus undermining the idea of a clear and definite law of color harmony.85 This, of course, was already evident in the fashion and interior-decorating industries. As Le Teinturier universel noted in 1860, “Manufacturers do not take color contrast sufficiently into account. In Paris, we can honestly say that store displays only succeed because of good taste or sometimes the eccentricity of the assortment of colors. Let’s keep it at this for now. Once we have presented the rules of good taste based on color contrast, we are convinced that we will produce new effects that no one has yet imagined.”86 However, for the silk manufacturers in Lyon, wool manufacturers in Lille and Roubaix, cotton printers in Mulhouse, and distributors of these goods, nothing could be more antithetical to their mode of thinking and operating than the suggestion that there was only one correct way to select and combine colors.

For retailers, challenging tastemakers’ authority was a routine part of doing business. In a catalogue published in 1889, the Grand Dépôt, a large Parisian tableware and ceramics store, drew a parallel between its fine and exotic goods on display and those visible at the state-sponsored Universal Exposition held the same year on the Champ de Mars. However, at the Grand Dépôt, the catalogue noted, the jury was made up entirely of shoppers, and it was they, not tastemakers, who established which products were most deserving of recognition: “Yes, it’s during this never-ending contest, this permanent exposition, where the verdict is delivered by consumers’ enthusiasm or indifference, it’s by way of this judgment originating from buyers or simple visitors that the grand dépôt emerges as the curator of exhibitions and that it can, with its incontestable experience, inspire artists and give to the French and English manufacturer their rallying cry, which they follow because they are disinterested and, however hard he works and confident he is in his product, the manufacturer produces for his clients, who condemn or judge him without right of further appeal.”87 The Grand Dépôt exaggerated consumers’ power over producers for strategic reasons. Still, the basic idea expressed in the catalogue holds true: manufacturers were willing to supply Parisians with all sorts of goods, so long as there was a demand for them, no matter tastemakers’ opinions. In looking at what was actually produced at the time, it is unsurprising, therefore, to find garments, wallpapers, ceramics, and other decorative household items that fail to meet Chevreul’s aesthetic standards (figs. 13 and 14).

FIGURE 13

Chevreul especially disapproved of the juxtaposition of different shades of red, as seen here. Woman in dress, Paris, 1880s. New York Public Library, New York, N.Y.

FIGURE 14

Catalogue of the Grand Dépôt (Paris), La céramique moderne par le Grand Dépôt (Paris: published by the firm, ca. 1885 [1889?]). Winterthur Library, Winterthur, Del.

Revisions or additions to Chevreul’s theory suggest that tastemakers, while recognizing the benefits of having a positive law of color harmony in order to curtail chromatic variety and confusion, were dissatisfied with Chevreul’s radically abstract and purely optical definition of color. The consequences of this way of understanding color were multiple. Chevreul vehemently rejected, for instance, traditional associations between color and music prevalent in Western science, art, and philosophy since antiquity.88 Musical harmony, he insisted, was entirely different from color harmony. “To overlook the fact that sounds have not until now shown any parallel to the simultaneous contrast of color,” he said, “is to misunderstand the phenomenon that most distinguishes colors from sounds; it is to renounce getting to the bottom of things because of a desire to see only resemblances.”89No matter the parallel’s deep cultural significance and distinguished ancestry, including Isaac Newton’s identification of seven primary colors corresponding to the seven tones of the musical octave, Chevreul maintained that the linkage was profoundly misleading and should therefore be avoided. “No one has been more aware of the abuse of analogy found in what several writers have said about colors and sounds,” he wrote.90

Taking this idea that color referred to nothing beyond itself into the realm of everyday life, Chevreul argued that women’s choice of dress should be based exclusively on their skin and hair color; the choice of furniture covering, on adjoining colors in the room. He was completely unconcerned with how fashion trends, cultural traditions, and personal preferences might inform consumers’ choices. Women posing for portraits, for example, were especially advised to follow his recommendations. For the law of the simultaneous contrast of color would lend the paintings “more brilliancy and harmony, render them thereby less susceptible of appearing antiquated when the prevailing fashion of [the sitter’s] time is forgotten.”91 But, as tastemakers quickly realized, the cost of creating aesthetic harmony and limiting bariolage according to Chevreul’s law was that color now referred to nothing beyond itself—it was no more than a visual and intellectual abstraction.

Color and the Meaning of Abstraction

After writing De la Loi du contraste simultané des couleurs, Chevreul became increasingly interested in the subject of abstraction as such. He published a series of philosophical texts, examining the topic from both epistemological and aesthetic perspectives, including, most notably, a series of letters to Abel-François Villemain published under the title Lettres adressées à M. Villemain sur la méthode en général et sur la définition du mot fait (1856) and De l’Abstraction considérée relativement aux beaux-arts et la littérature (1864). In these works, Chevreul was primarily concerned with defining the relationship between abstract ideas and individual facts in human reasoning and in the arts. Reflecting on the methodology that had inspired his scientific research up to that point, Chevreul argued that abstract ideas and concrete facts entertained a symbiotic relationship to one another. “All told,” he wrote, “I come to the conclusion that the concrete can only be known by way of the abstract and, considering that all our ideas are nothing but abstractions, that facts are only precise abstractions.”92 In other words, Chevreul rejected the empiricist belief in the primacy of concrete facts over abstract ideas. Concrete facts were not transparently imprinted onto the mind and juxtaposed, conjoined, and synthesized to form abstract ideas. Rather, abstraction played an appreciable role from the very start of the intellectual process. “If we only know living things from their ways of being, faculties, properties, qualities, that together create a whole to which we give a specific name, you see how here as well, proceeding by way of analysis, we arrive at abstractions, which are the facts corresponding to the chemical substances’ properties [propriétés des espèces chimiques].”93 This was especially true in the case of chemistry, where molecules and the atoms that composed them were invisible to the naked eye. The molecule—or l’individu chimique, as Chevreul called it—was a theoretical construct of the first order. “In no science of the visible world [science du monde visible] does the necessity of linking precise facts of observation, obtained by controlled experimentation, not lead to the creation of intellectual concepts that are beyond empirical demonstration,” Chevreul asserted.94

Like scientific properties, Chevreul defined the basic elements of artistic composition as abstractions. No matter how realistic, artworks were never exact reproductions of reality: “Obviously, sculpture and painting can only represent some of [the model’s] attributes; they speak to the eyes only by means of abstractions selected from a whole, chosen because of a desire to embellish it, to ennoble it in the image whose appearance will thus be rendered more beautiful, more moving, or more terrible even according to the artist’s intention.”95 Color, therefore, was a prime example of an abstraction according to Chevreul. Before existing in the form of a specific object or image, color existed as abstract intellectual property, as, for example, the idea of blueness, whiteness, redness, and so on.

This elision between color and abstraction (and vice versa) was not, in fact, unique to Chevreul but had a long history in Western thought. Already in the early modern period, abstraction was connected to color. In Denis Diderot and Jean le Rond d’Alembert’s Encyclopédie, for example, César Chesneau Dumarsais drew upon the idea of whiteness to illustrate the concept: “Thereby noticing in the chalk or in the snow the same color that, yesterday, milk evoked in my mind, I consider this single idea, I treat it as a representation of all others of the same type, and giving it the name of whiteness, I express with that word the same quality, wherever I might imagine or encounter it, and this is how universal ideas and the terms that we use to designate them are formed.”96 The term abstraction indicated both the mental process by which the color was considered apart from line and form and the color itself. Whiteness was abstracted from the chalk, snow, and milk, and whiteness was also the abstraction.

Chevreul’s treatment of color as an abstraction, isolated from the other characteristics under which it presented itself in everyday visual and material culture, therefore drew upon a centuries-long intellectual tradition. What was new about Chevreul’s theory from the perspective of fashion experts and the broader general public, however, was the notion that colors had no meaning above and beyond the optical impression they provided. Indeed, according to Chevreul’s understanding, color was an abstraction both in the traditional sense of a property “abstracted from” a given setting or context and in the more modern or, one might say, modernist sense of a purely visual, self-sufficient, nonreferential sign.97 Chevreul’s redefinition of the exact nature of color’s abstraction collided with collective categories of visual experience and understanding, such as those introduced by Raymond and Blanc, among others, which foregrounded colors’ expressive and symbolic qualities. Thus, on the one hand, the reception of Chevreul’s theories among tastemakers points to cultural elites’ common effort to restrain what was viewed as the deterioration of French taste by the multiplication of inexpensive goods in an ever-widening assortment of colors. On the other hand, it demonstrates how, even within the limited circle of tastemakers writing on fashion and decoration, there was no consensus about how color should be defined and employed.

According to literary critic Christopher Prendergast, bariolage was “a key term in the perceptual vocabulary of the later nineteenth-century literary equivalents of Impressionism, from Rimbaud to Zola, and a complex nodal word in the representational economy of the nineteenth-century urban imagination.”98 More than simply a shorthand for the representational practices associated with Impressionism, however, the term points to a novel aesthetic experience grounded in the material and visual culture of the period. A term often associated with crowds, bariolage had a social dimension as well, related to the unprecedented commingling of people from different realms and the particular tension between variety and unity exemplified by modern urban life.99 And indeed, for many tastemakers, the struggle for aesthetic harmony was also very much a struggle for social order. “The conflict between conformity and individualism must be, to a certain extent, the theme of every modern history, in every country. In France, however, the conflict has involved a great deal of polemic and it has been obscured by value-judgments,” Theodore Zeldin points out.100 In the second half of the nineteenth century, these value judgments often concerned matters of color and taste. Rather than focus on the social and political agendas of these arbiters of French taste, however, this chapter has sought to illuminate the categories of experience and interpretation that tastemakers and cultural observers writing in the middlebrow press used to understand and thus control color.

The early expansion of the industrial palette, in the first half of the nineteenth century, prompted Chevreul to devise a scientific method for the identification and classification of colors and to transform his law of the simultaneous contrast of colors into a general program for the elevation of public taste. The emergence of new synthetic dyes, however, quickly rendered Chevreul’s color wheels obsolete. Indeed, despite their initial enthusiasm for the chemist’s system, textile producers soon put aside their nascent plans to standardize the production of color in favor of the enthusiastic and uncoordinated pursuit of novelty and variety.

All was not lost for Chevreul and his theories, however. For producers and consumers seeking guidance in this new world of increasing chromatic novelty and variety, Chevreul’s principles of color harmony reemerged in the second half of the nineteenth century, more attractive than ever. Fashion and interior-decorating experts added credence to the chemist’s theories, in particular the idea that the juxtaposition of complementary colors created an especially harmonious effect. More importantly, perhaps, Chevreul and those who popularized his law of color harmony encouraged French men and women to pay attention to colors’ subtle variations, the effects created through their juxtaposition, as well as to simply enjoy color for its own sake, apart from its representational function. As a result, the idea of color-as-abstraction gained new significance and currency. Contrary to Chevreul, however, who insisted that color was an abstraction that meant nothing beyond itself, tastemakers highlighted color’s expressive and symbolic functions. The experience of color was not only optical, they argued, but also psychological and cultural.

These ways of thinking about and looking at color constitute a far more important legacy than Chevreul’s color wheels or laws of color harmony, however widely diffused. For indeed, as evidenced by store catalogues, fashion plates, and tastemakers’ constant talk of the optical distress caused by Parisians’ poor fashion and interior-decorating choices, the type of harmony that elites dreamed about was seldom achieved in reality. In the 1890s, Charles Lacouture, author of his own répertoire chromatique, wrote that Chevreul’s ideas had failed to gain widespread acceptance:

Thanks to his untiring efforts and perseverance with the same studies during his century-long existence, the revered and illustrious scientist significantly advanced the practical study of colors. He supplied definitions, laid the foundations for a methodical nomenclature, established principles and laws, represented a great number of types, etc.; it was a very real step forward. But, it must be acknowledged that the ordinary scientist as well as the general artistic or industrial public did not greatly experience this progress; they did not benefit from it as much as one would have expected. The proposed nomenclature never entered into common usage; the laws of the simultaneous contrast of colors, successive contrast or mixed, are sometimes referenced but often incorrectly; the color wheels are rarely employed.101

Pointing to Impressionists’ and Neo-Impressionists’ juxtapositions of bold, contrasting colors, art historians’ assessment of Chevreul’s influence is a resounding success story in comparison. If asked to identify the most successful application of his theories, Chevreul himself, however, would probably have pointed not to painting but rather to the flower garden created under his supervision at the Muséum national d’histoire naturelle in the 1860s. Organized in concentric circles of contrasting colors, the Carré Creux shows how, alongside fashion and interior decoration, floriculture, too, was taking a dramatic turn toward color during this period, as we shall see in the following chapter. As this chapter has argued, however, Chevreul’s success in shaping the fine arts, industrial arts, or public taste matters less than what the project itself indicates about how color transformed nineteenth-century visual and material culture and the new mental tools and visual practices that emerged during this radical transformation in the look and feel of everyday life.