The name that brothers Francisque and Joseph Renard picked for their new aniline dye has a complicated etymology. Fuchs is the German word for “fox,” which in French is renard. Thus, by naming their dye fuchsine, or “fuchsin” in English, the Renard brothers marked the pinkish-red color as theirs and theirs alone. It was, they insisted, a branded commercial product with a distinct technological, commercial, and cultural identity. For the bulk of consumers, however, the name fuchsine would have most likely evoked the brilliant reddish-purple hues of the fuchsia flower, a favorite among nineteenth-century gardeners.1 This, too, was a calculated move on the part of the Renards. In naming their dye after a flower, they followed the recent example set by William Henry Perkin, who eventually settled on mauve, the common French name of the mallow flower, for his new violet dye.2

But it would be a mistake to conclude from these horticultural references that Perkin or the Renard brothers wished to pass off their new dyes as natural products or somehow occlude their synthetic origins. For chemists working in factory settings, as well as members of the general public who encountered references to these new synthetic dyes in newspapers, fashion magazines, and the marketplace, the suffix -ine quickly became synonymous with the marvels of coal-tar chemistry. In fact, according to an article in the French newspaper Le Temps, it was precisely fuchsin’s and other aniline-based dyes’ unusual chemical origins that allowed them to rival the colors of flowers as no other natural dye had done before. “Fuchsin, in all its many variations, perfectly reproduces the precise balance of red and violet that together create the color of the rose, without a hint of black to tarnish its incomparable brightness,” the journalist wrote, oddly sidestepping the more obvious fuchsia comparison.3

In contrast to the common mallow flower that gave Perkin’s dye its name, fuchsias are not native to France or even Europe.4 Indeed, several of the species known to gardeners in the mid-nineteenth century, such as Fuchsia corymbiflora and F. cordifolia, had only been introduced to Europe relatively recently. From the 1820s to the 1850s, botanists and flower hunters working in Mexico, Chile, Peru, and other parts of Central and South America imported hundreds of new fuchsia species to Europe, spurring interest in the flower among horticulturalists, nurserymen, and gardeners, who quickly embarked on the project of transforming the exotic shrub into a common fixture in European gardens and homes (fig. 15).

FIGURE 15

Henri-Joseph Harpignies, A Potted Fuchsia with Children’s Toys, 1877. Watercolor. National Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C. Ruth and Jacob Kainen Memorial Acquisition Fund, National Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C. Courtesy of the National Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C.

The process by which this happened was not simple or straightforward. Through intense selective breeding and hybridization, plant breeders created new varieties of fuchsias in an ever-widening array of shapes and colors. The first double fuchsias with multiple overlapping petals were introduced around 1850. A few years later, English gardener and horticulturalist W. H. Story introduced six different varieties of fuchsias with white petals—a striking novelty at the time. Variegated fuchsias in a rich mixture of hues soon followed, including the ‘Striata’ and the ‘Perugino’, the latter named after the great Renaissance painter.5 In short, fuchsias commonly seen in French gardens in the second half of the nineteenth century were much larger than those in the wild and far more varied in their coloring. They were, as one late nineteenth-century source put it, “a plant that has been rigorously worked on by our florists.”6

In selecting the name fuchsine for their new dye, the Renard brothers were not, therefore, so much referencing nature as the novelty and color-driven world of horticulture and gardening. Like the fuchsin-colored dresses, hats, and fashion accessories that appeared in women’s wardrobes starting in the 1860s, the fuchsias Parisians knew and loved were artificial products, made fashionable by color. This was true not only of fuchsias, of course, but of virtually all ornamental flowers. White, yellow, red, orange, pink, violet, and myriad other shades in between, flowers participated in the general transformation of nineteenth-century visual culture through color alongside synthetic dyes, chromolithography, and other color technologies. Floriculture and the commodity culture that produced colorful goods and images—from garments and paintings to fireworks and prints—were, indeed, intimately and firmly intertwined.

No longer simply the affair of a few nurserymen catering to wealthy amateur plant collectors, the growing and selling of flowers became a specialized and increasingly sizeable industry in France starting in the mid-nineteenth century, as gardening became a fashionable hobby for the middle classes and it eventually became possible for members of the working class, too, to spend resources on such evanescent pleasures as flowers. Indeed, if not exactly products of standardized appearance and quality, flowers seen in gardens and bouquets were nevertheless mass commodities in the purest sense. Imported from all over the world; hybridized, grown, and cared for in commercial nurseries; advertised in catalogues; and sold in open-air markets, kiosks, and boutiques—flowers were designed for immediate and renewed consumption, very much like newspapers, drink, and food, not to mention the many fleeting entertainment and leisure activities that came to characterize modern urban life.

The popularity of flowers ebbed and flowed according to consumers’ tastes, which those in the flower business attempted simultaneously to serve and manipulate with varying degrees of success. As we shall see, in their efforts to present consumers with something novel and eye-catching, plant breeders specifically focused on color. As part of this process, new varieties of flowers and the gardens that featured them became increasingly defined by the imperatives of commodity capitalism, most notably the perpetual quest for novelty and variety that characterized the fashion industry. In their efforts to invent new colors and heighten their visibility through clever juxtapositions, plant breeders, landscape artists, and gardeners promoted a specifically and intensely visual experience of flowers and gardens. This new modus operandi effectively blurred the distinction between the artificial and the natural—the latter defined as an original state of being untouched by human art. By the same token, through their promotion and display of new hybrid flowers, landscape artists, florists, and the French men and women who took pleasure in their creations increasingly came to treat flowers as colorful commodities, just as subject to the whims of fashion as women’s garments.

While evident elsewhere in Europe and the United States, this phenomenon was particularly visible in Paris, which saw the creation or redesign of two thousand hectares of parks, gardens, and squares between 1853 and 1870—and whose inhabitants, contemporaries noted, had an immoderate taste for both flowers and fashion.7 For the most part, Parisians celebrated this transformation of their visual surroundings, as demonstrated by the popularity of the city’s new public spaces and the crowds that gathered at the city’s outdoor flower markets. Nevertheless, a number of flower and landscape professionals resisted these changes, which they viewed as an assimilation of horticulture and garden design by the fashion industry and thus a potential threat to their status as tastemakers. Theirs, they insisted, was an art inspired by the eternal principles of beauty, not the evanescent trends of fashion.

Curiously, this suspicion of fashion and color for its own sake also found its expression in the artificial-flower industry. Commonly worn on hats, bodices, and even skirts, artificial flowers were an essential nineteenth-century fashion accessory. Still, rather than simply producing something pretty and new, a number of high-end flower makers insisted on the importance of producing only flowers that existed in nature, however artificial the natural world had in fact become. Blindly following fashion, they insisted, was ill advised, since only by carefully reproducing nature could flower makers demonstrate their skill and justify their wages. The pressure to come up with new, inexpensive, and eye-catching models was so pronounced, however, that many flower makers produced fleurs de fantaisie, that is, imaginary flowers in imaginary colors. Thus, while the demand for color led horticulturalists and garden designers to trespass into the realm of the artificial, many flower makers were compelled to travel from the real to the imaginary.

Moving back and forth between categories of the natural and the artificial, the real and the imaginary, this chapter shows how these ideas were interwoven in the second half of the nineteenth century, defining a distinctly modern way of seeing. It sheds light on the gradual overlapping of nature and commerce and the important role that color played in that process. The pursuit of color, I suggest, was not merely about adding a touch of fancy to everyday life, nor was it achieved through synthetic chemistry alone.8 The hybridization of flowers, the spread of bold monochromatic or contrasting flower beds, and the manufacturing of artificial flowers in an ever-widening array of hues fundamentally destabilized the relationship between the natural and the artificial, the real and the imaginary, to say nothing of that between color and form. These processes shifted dominant categories of visual perception and signification, affecting how French men and women perceived, imagined, and depicted their place in the world.

From small still-life paintings to elaborate decorative panels, Impressionists’ iconic interpretations of flowers and flower gardens readily come to mind when considering the significance of color in nineteenth-century visual culture. The way that French floricultural modernity and artistic modernism intersected and overlapped in these artists’ paintings provides access to important cultural insights and marks the question of how French men and women perceived color as especially meaningful. As this chapter emphasizes, however, Impressionism emerged in an already evolving visual field, in which the natural merged with the artificial and the real with the imaginary, and horticulturalists, nurserymen, garden experts, florists, and artificial-flower makers reenvisioned the urban landscape as an arrangement of vivid dabs of color.

Chevreul’s Color Theories and the Scientific Art of Gardening

Forgoing symbolism, sentiment, and musical analogies, Michel-Eugène Chevreul encouraged his diverse audiences—scientists, manufacturers, artists, and consumers included—to contemplate color as an independent, interchangeable, and mobile quality. Indeed, as detailed in the previous chapter, his theories offered a new and influential way of understanding the connection between color and abstraction, not only from a purely scientific or philosophical standpoint, but also in more quotidian practical contexts, in particular those related to dye and textile production in nineteenth-century France. Yet there is more to Chevreul and his theories than what can be gleaned from his ties with these industries, however important such industries were to the French economy and supportive of the chemist’s work.

From a personal standpoint at least, Chevreul was equally, if not more, interested in flowers and gardens than he was in dyes and textiles. “Dahlias have for a long time engaged my attention,” he noted in De la Loi du contraste simultané des couleurs.9 Indeed, like so many men of his class and education, Chevreul was an amateur horticulturalist and gardener, who made no secret of his love of flowers. “You mentioned in conversation that you were very fond of flowers. At Wand-worth, where I live, there is the finest collection of orchidious plants and heaths in England,” wrote a candle manufacturer, encouraging the chemist to take advantage of his presence in England for the 1851 Great Exhibition to see the rare collection.10 It is unclear whether Chevreul accepted the invitation, although he must certainly have been tempted. He had extensive knowledge of flowers and flower gardens and, through his many years of thinking and writing about color, had developed definite opinions on the topic.

For further evidence of Chevreul’s fondness for flowers one need look no further than De la Loi du contraste simultané des couleurs, in which one of the longest sections—longer even than that related to men’s and women’s clothing—pertains to the display of colors in gardens. Following from the advice he presented elsewhere in the book, Chevreul encouraged gardeners to create beds and borders made of sharply contrasting, generally complementary colors. Subtle variations of analogous hues—a combination of oranges and reds, for instance—were to be generally avoided: “Such arrangements as these cause the eye, accustomed to appreciate the effect of contrast of colors, to feel sensations quite as disagreeable as those experienced by the musician whose ear is struck with discords.”11 His, he insisted, was a scientific approach to gardening, guaranteed to produce the most agreeable visual effects: “It is evident that after stating the Law of Simultaneous Contrast of Colors, distinguishing their various kinds of harmonies and their associations with white, black, and grey, the grouping of flowers will present no difficulty, since it will only be a simple conclusion from facts previously studied under all the relations which concern horticulture.”12 Gone, in other words, were the days when the selection of flowers was determined by chance, tradition, or sentiment.13 Indeed, committed to transforming the garden design into something simultaneously more scientific and more tasteful, Chevreul urged his readers to understand flowers first and foremost by and through their colors.14

Chevreul not only recommended color combinations in the abstract, as it were, but also provided examples of specific flowers that could be used to create color schemes at different times of the year. In the month of February, for example, Chevreul proposed that gardeners use white, yellow, and violet crocuses. In June, the same color scheme, he explained, could be achieved with white, yellow, and violet pansies. Familiar with species’ flowering seasons and their common and scientific names, Chevreul was clearly no gardening novice. More than merely another incidental testing ground or application, the garden was, in his view, a privileged place for testing his theories and delighting in the pleasures of color. Indeed, during the ten years prior to the publication of De la Loi du contraste simultané des couleurs, he tested his theories in the large garden adjoining his house in L’Haÿ.15 The precise type of flowers that grew there and the exact nature of the tests remain unclear. It is interesting to note, however, that while the Chevreul family resided in L’Haÿ a vibrant flower industry developed in the surrounding villages of Fontenay-aux-Roses and Bourg-la-Reine to supply the nearby Parisian market. According to Armand Millet, a horticulturalist and flower grower active during the late nineteenth century, by “about 1838 at the village of Fontenay-aux-Roses all the fields that were not being used for roses were covered in violets.”16 Chevreul elaborated his theories within a specific material context. And, next to the dyes and textiles of the Manufacture des Gobelins, it is not hard to imagine flowers playing an important role in shaping the chemist’s thinking about color. The view of the nearby fields must, in any case, have been breathtaking.

Certain flowers, namely roses and violets, are especially lauded for their sweet fragrance. According to Chevreul, however, flowers and their display in gardens constituted an almost exclusively visual experience:

Among the pleasures afforded us by the cultivation of choice plants, there are few so intense as the sight of a collection of flowers, varied in color, form, and size, and in their position on the stems that support them. If the perfume they exhale has been extolled by the poets as equal to their colors, it must be admitted that they never create, through the medium of sight, disagreeable sensations analogous to those which some nervous organizations experience from their exhalations through the sense of smell. Color, then, is doubtless, of all their qualities, that which is most prized.17

Disagreeable or not, the smell of flowers was nowhere analyzed by Chevreul. It did not occur to him, for example, that in addition to having a harmoniously colored garden one might wish to create one that was delightfully fragrant.

For Chevreul, the garden was not simply about demonstrating humankind’s mastery over nature or creating an enchanting landscape suitable for the contemplation of picturesque attractions but rather constituted a unique occasion for visual display and pleasure measured in degrees of colorfulness.

Chevreul’s scientific management of the garden experience through the privileging of color is further evidenced in the flower garden completed by Joseph Decaisne at the Jardin des Plantes in or around 1866, the design of which was directly inspired by the chemist’s theories of color perception.18 From the Carré Creux’s sunken location to its bright contrasting colors, everything about its design was meant to heighten the visual experience of visitors. The garden appeared as a large circular bed of flowers divided into concentric circles of contrasting color (fig. 16). Several sources, ranging from horticultural treatises to guidebooks, noted how the flowers had been juxtaposed according to the most recent scientific theories of color perception, some even mentioning Chevreul by name: “In an immense flower bed that reaches the Galleries, one notices a square dedicated to the cultivation of ornamental perennial flowers that have an unusual vividness. This vividness is an optical illusion and the effect of the flowers’ clever placement. [Gardeners, that is,] simply applied the laws of the simultaneous contrast of color discovered by Mr. Chevreul. With the help of its neighbor, each flower makes a greater visual impact than when considered alone. Isolated, it would lose the marvelous coloring that only a skillful juxtaposition can produce.”19

FIGURE 16

Pierre Lamith Petit, Carré creux, ca. 1889. Photograph. Muséum national d’histoire naturelle, Paris.

Chevreul began teaching chemistry at the Muséum d’histoire naturelle in 1830 and served several tenures as director of the famed scientific institute, all the while maintaining his position as director of the dyeworks at the Manufacture des Gobelins.20 Decaisne had an equally long-standing relationship with the institute. He entered as a student in 1824 and occupied a variety of lower-level posts before rising in 1850 to the prestigious position of professeur de culture, which he held until his death in 1882. In other words, the line of influence between Chevreul and Decaisne was a direct one, and the flower garden was a carefully planned and purposeful demonstration of the former’s color theories.

Indeed, according to an early description of the Carré Creux published in 1863, the layout of the garden closely followed Chevreul’s precepts. In the summer, for instance, the central section was planted with mostly green leafy plants, surrounded by a row of “red” Geranium anemonæfolium, followed by a row of “yellow” marigolds, and then a row of “blue” Lobelia erinus. Meanwhile, the adjoining border featured red Pelargonium zonale and yellow marigolds, appropriately separated by a row of white Petunia nyctaginiflora.21 Indeed, as Chevreul originally noted in De la Loi du contraste simultané des couleurs, “White flowers are the only ones that possess the advantage of heightening the tone of flowers which have only a light tint of any color whatever. They are also the only ones that possess the advantage of separating all flowers whose colors mutually injure each other.”22

Chevreul found a knowledgeable and ready collaborator in Decaisne. As a young man, he studied painting and assisted his brother, Henri Decaisne, in the making of color lithographs. Indeed, the taste for color seems to have run in the Decaisne family. A pupil of early Romantic artists Antoine-Jean Gros and Anne-Louis Girodet de Roussy-Trioson, Henri Decaisne eventually moved on from lithography to become a successful Academic painter.23 Meanwhile, one of Joseph Decaisne’s first scientific treatises, published in 1837, focused on the anatomy of the madder plant, an important natural dyestuff.24 Perhaps more than any other member of the Muséum, Decaisne understood and shared Chevreul’s unique appreciation for both scientific and aesthetic dimensions of color and the ways in which the latter could be improved through the thoughtful study of the former.

Compared to his work at the Manufacture des Gobelins, Chevreul’s position at the Muséum allowed him more freedom to study and simply enjoy flowers. The little house where Chevreul resided on weekdays while his wife was still alive, and then full-time after her death, adjoined the flowered grounds of the Jardin des Plantes. There, he rubbed shoulders with not only influential botanists, horticulturalists, and gardeners, such as Decaisne, Charles Victor Naudin, François Hérincq, and Pierre-Bernard-Lazare Verlot, but also flower aficionados from the general public. Flowers remained for the chemist an important and constant interest. In fact, in an official report reviewing Chevreul’s chemistry course and direction of the Gobelins’s laboratory, the author complained about the misdirection of resources: “This year, it is flowers that we had to classify. And it is not just hours, or days, but entire months that were spent on this task. So it is hardly surprising that there was a significant slowdown of production in the dyeworks department.”25 In other words, according to this reporter, the chemist’s interest in flowers was hardly peripheral but was actually getting in the way of progress on more urgent and relevant matters involving dyes. Chevreul, however, seems to have enjoyed dividing his attention among these various pursuits. His final word on his system for scientifically identifying and naming colors was a nine-hundred-page memoir, presented to the Académie des sciences in 1861; approximately five hundred of these pages were dedicated to identifying the colors of flowers.26

If colorful flower beds eventually became commonplace in nineteenth-century Paris, Chevreul and his laws of color harmony must receive at least partial credit. Surely, his dismissal of flowers’ scents as merely secondary to the pleasures afforded by their colors was somewhat eccentric and hardly representative of nineteenth-century flower enthusiasts as a whole. Furthermore, there is little evidence that gardeners universally or even generally followed Chevreul’s laws of color harmony; outside the Carré Creux, the selection and combination of colors in Parisian gardens obeyed far more fluid and elusive rules, if any at all. Echoing what certain tastemakers said about Chevreul’s influence in the realm of fashion and interior decoration, landscape artist Édouard André estimated that, “in practice, we will find that his laws are rarely taken advantage of. Most of them are a dead letter to gardeners, who are satisfied with fantastical juxtapositions and give little thought to their floral combinations.”27 Nevertheless, along with his collaborators at the Muséum and those who disseminated his laws of color harmony, Chevreul was one of the original and most ardent promoters of an ocularcentric understanding of garden design that would become increasingly important in the second half of the nineteenth century, as the variety and novelty of flowers’ colors became the main focus of horticultural innovation and flower sellers’ marketing strategies.

Fashionable Flowers and Flower Gardens

While France was the uncontested leader in fashion during the nineteenth century, England took first place in horticulture and garden design. Thus, despite early criticisms from French landscape professionals, who believed that the popularity of English gardens had led to the wrongful neglect of flowers, it was only when the English began taking more of an interest in flowers—wedding undulating lawns and serpentine walkways with the most impudently artificial and brightly colored flower beds reminiscent of French formal gardens—that a new, hybrid style of garden was truly established. This trend originated in the 1830s and 1840s, in direct response to the importation of colorful annual flowers from Asia, South America, Africa, and other faraway lands.28 Promoted by influential horticulturalists and gardeners such as John Claudius Loudon, the style quickly spread to France, where it resonated with the nationalist sentiments of landscape professionals and became the standard not only for large country estates and private suburban gardens but also for public parks, squares, and gardens in the capital.

The mixed, or composite, style is identifiable by its sharply defined monochromatic or multi-colored flower beds, ranging from elaborately patterned examples known as parterres (such as the Carré Creux) to the smaller, raised oval or round flower beds called corbeilles. Sacrificing the beauty of flowers’ individual forms, gardeners packed the plants closely together—a technique known as bedding out—in order to achieve a more powerful chromatic impression.29 Types of flowers that enjoyed special popularity for this purpose included lobelias, calceolarias, verbenas, and pelargoniums—the latter the genus of the common geranium. Imported from exotic locales, sprouted and cared for in greenhouses, subject to intense selective breeding and often hybridization, the species and varieties featured in French gardens were bright and colorful and frequently quite recent additions to the gardener’s repertoire.

In the eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries, the introduction of new flowers was generally the result of the efforts of flower hunters, who traveled the globe under the sponsorship of royal scientific societies or private nurseries.30 By the period under consideration here, however, hybridization had largely taken over as the preferred method of multiplying the types of flowers available in Europe. Exchanges now more often took place between the reproductive organs of one species of flower and the pollen of another than between continents.31 Already in 1845, the Belgian horticultural journal Flore des serres et des jardins de l’Europe proclaimed that hybridization was “the true conquest of our age . . . the procedure which means that, just like the Creator, man too may create plants virtually at his convenience, and may say, again just like the Creator: you, be born, and be of such and such form . . . ! Divine power! Infinite resource!”32 In reality, hybridization (the breeding of one species with another) and crossing (a more general term to describe the breeding of one variety with another) were far more complicated and uncertain undertakings.33 Still, their impact on the modern flower garden can hardly be overstated. As English botanist Maxwell Masters explained, by the end of the nineteenth century hybridization had become so common that “if [horticulturalists] went into present-day gardens they found that nine-tenths of the plants were the productions of the gardener’s art, and not natural productions.”34

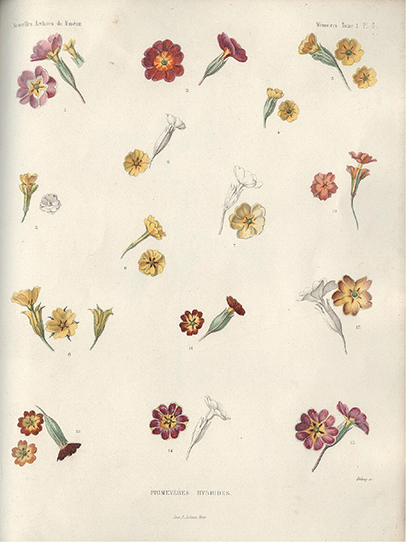

In their efforts to combine the characteristics of one species or variety of flower with those of another species or variety, the goals of plant breeders—a diverse group including horticulturalists, nurserymen, seed sellers, wealthy amateur plant collectors, and gardeners—remained largely the same over the course of the nineteenth century: sturdier, healthier plants, bigger blossoms, and brighter, more varied colors. From early scientific treatises to seed sellers’ catalogues, sources from the period all testify to the intense interest that horticulturalists and nurserymen took in color, which quickly became the main focus of innovation.35 Figure 17, from Muséum d’histoire naturelle botanist Charles Naudin’s Nouvelles recherches sur l’hybridité dans les végétaux (1862), for instance, shows how the crossing of yellow and burgundy primroses resulted in variegated—part yellow, part burgundy—flowers. That these hybrid flowers were not a uniform intermediate orange color was of special importance according to Naudin. Unaware of Gregor Mendel’s law of genetic inheritance, which explains how different traits function as independent properties and combine in varied but generally predictable ways, Naudin hypothesized that this variability was the result of a “disjunction” between the “essences” of the crossed specimens. Color functioned as the preferred method of demonstrating the combination of characters from parent plants. Indeed, hybrids, Naudin suggested, could be imagined as “living mosaics,” in which each trait operated as a small colored tile, which could be shuffled and reshuffled in multiple combinations.36

FIGURE 17

Charles Naudin, Nouvelles recherches sur l’hybridité dans les végétaux (Mémoire présenté à l’Académie des sciences en décembre 1861), vol. 1 (Paris: s.n., 1862), plate 3.

The importance of flowers’ colors in commercial horticulture is further demonstrated in the catalogues and advertisements of European seed sellers, gardening manuals, and articles in popular scientific journals. In their multivolume work Manuel de l’amateur des jardins (1862–71), longtime collaborators Naudin and Decaisne, for instance, noted how many of the hybrid verbenas “differ from one another principally by the color of their flowers, among which we can now find all the shades of pink, carmine, crimson purple, violet, violet blue, and even pure white.” “Most of these varieties,” they added, “are a single color, but there are also some that are variegated, marbled, and starred, as a result of the manifold combinations of two different colors.”37 For these horticulturalists and their flower-hybridizing followers, nature was not simply given but always receptive to transformation and improvement: where only single flowers existed, double flowers were brought into being, and where there had once been only white flowers, colored ones were created. Confirming what by then was a long-standing trend, Albert Larbalétrier noted in the journal La Nature, “We know that in horticulture it is not only form and odor but especially color that is today the focus of the quest for new varieties.”38 In floriculture as in fashion, color was what distinguished this year’s offerings from last year’s; it added an aura of novelty to otherwise identical products. And, just as in the fashion industry, where the demand for color and the invention of synthetic dyes challenged common understandings of the natural and the artificial, the trend toward color in gardens involved a blurring of the aesthetic and ontological boundaries separating the God-given from the man-made.39

It was in this context, characterized by the industrial production of flowers and volatile horticultural trends, that geraniums (in particular, Pelargonium zonale and P. inquinans) rose to prominence. “There is no garden, however modest, that does not have a couple of corbeilles of them, and even in gardens where the rarest and most varied flowers encounter one another, these pelargoniums still hold an important place,” noted a well-known guide to garden flowers.40 Introduced in the seventeenth and early eighteenth centuries, the pelargoniums that found their way to Europe crossed easily with one another, giving rise to many accidental hybrids. Indeed, already in the early nineteenth century, horticulturalists observed that many of the pelargoniums seen in European gardens and greenhouses no longer resembled the original species found in their native South Africa. Some of these new European varieties were probably engineered. However, since early nineteenth-century hybridizers rarely kept records of their activities, the new varieties they created were quickly confused with those that had occurred naturally as a result of spontaneous cross-pollination. Specialists’ efforts to determine the parentage of specific varieties had only limited success: varieties continued to be mistaken for bona fide species, and few horticulturalists had any suggestions for how to definitively resolve this taxonomic mess. In 1838, the influential garden writer Charles M’Intosh went so far as to declare the whole genus a “botanical chaos”—with little effect, it should be noted, on hybridizers’ activities or the pleasure that consumers derived from the novelty and variety of their creations.41

The first confirmed hybrid pelargoniums, created through deliberate crosses, appeared in nurseries and flower markets during the early 1840s.42 Many more were introduced in the following decades, as hybridizers, now increasingly located in France, worked to create geraniums with rounder, bigger, and brighter flowers. These included more compact dwarf varieties particularly well suited to bedding out, such as the ‘Tom Pouce’. White varieties, such as the aptly named ‘Boule de Neige’, as well as pink and peach-colored examples, became more and more common in the mid-nineteenth century. By the end of the century, Henri Dauthenay estimated that there were three thousand varieties of Pelargonium zonale and P. inquinans alone, a large percentage purposefully created through artificial fertilization.43

Again, as evidenced by how these flowers were displayed in gardens, geraniums and other exotic species and hybrid varieties owed their particular appeal to the brightness and variety of their colors—something especially well documented in Impressionists’ paintings. Long before the creation of his famed garden in Giverny, Claude Monet, for example, was already extremely attentive to the effects of color created by flowers. In his Woman in the Garden (fig. 18), the red flower bed at the base of the tree, composed of what seem to be geraniums, contrast sharply against the complementary green surroundings. The flower beds in this and other paintings from his early career, composed of almost identical bright red touches of paint, speak to the standardization and commodification of French floriculture. These are not wildflowers haphazardly gathered by Mother Nature, nor do they pretend to be; they are instead carefully grown, purposefully displayed home accessories originating in the catalogues of nurserymen and commercial seed sellers.

FIGURE 18

Claude Monet, Woman in the Garden, Sainte-Adresse, 1867. Oil on canvas. The State Hermitage Museum, St. Petersburg.

Painters and well-to-do gentlemen held no monopoly on the interest in flowers. International observers remarked on the strong taste for flowers among all social classes in France. Parisians who could not indulge their horticultural fantasies by cultivating their own garden traveled to public parks and botanical gardens, decorated their windows with flower boxes, and purchased pots and bouquets at the city’s numerous flower markets. “There are thousands of Parisians whose garden is the window-sill, or a basket mossed over in the sitting-room, or a glazed case, and to most of them the flower-market is a nursery; and an excellent nursery too, for they can get there numerous pretty plants in the best of health for a trifling sum,” wrote the influential English gardener and journalist William Robinson in 1869.44

Flower markets and florist shops played a key role in disseminating horticultural novelties and the popular taste for flowers. Especially noteworthy is the way that florists capitalized on the sensual appeal of their merchandise—in particular, colors—to attract passersby. “Florists are . . . very preoccupied with their displays. You will not believe to what extent a true florist is an accomplished artist. It is important that he assembles colors as a colorist would, arranges his assorted flowers in sweet-smelling arabesques, [and] creates bouquets with new, harmonious, eye-catching colors,” noted Le Gaulois in December 1880.45 Here again, there is little evidence to suggest that flower sellers had absorbed Chevreul’s laws of color harmony. In selecting and juxtaposing their bouquets, they imitated not so much the chemist or artist as the department store manager who created visually jarring, yet seductive, displays of colorful merchandise.46 The juxtaposition of colorful bunches of flowers was not left to chance; it was a studied spectacle designed to stimulate desires of fantasy and consumption.

Descriptions of florist shops such as the one in Le Gaulois elucidate several aspects of Parisian visual culture that were shaped by the buoyant consumerism of the second half of the nineteenth century. In particular, contrary to the description of Haussmannian Paris as uniformly gray, this passage reminds us that the monochromatic cityscape was disrupted every few blocks by displays of flowers among other colorful sights. Like the Morris column plastered with posters and the department store window, florists’ shops, stands, and carts summoned Parisians with their bright colors. In fact, as documented in one of Eugène Atget’s photographs from the series Vie et métiers à Paris (1898–1900), circular kiosks plastered with posters sometimes served as florist stands (fig. 19). Together, the flowers and posters visually transformed the urban landscape into a polychromatic configuration that encouraged viewers to appreciate color on its own terms, divested from the formal characteristics typically associated with figurative representation.

FIGURE 19

Eugène Atget, Luxembourg boulevard St. Michel (marchand de fleurs), in Vie et métiers à Paris series, 1898–1900. Photograph. Département des Estampes et de la photographie, Bibliothèque nationale de France, Paris.

The connection between consumer culture, color, and flowers was also promoted by Parisian department stores. For instance, the Magasins Réunis, opened in 1867, had a garden in its interior court.47 Clients could peruse the garden’s flowers in the same spirit and with the same gaze with which they examined the colorful products sold inside.48 Le Printemps, a department store opened in 1865, explicitly presented itself to viewers as a bountiful garden. “Le Printemps is a garden of industry where the products of nature transform themselves into light textiles, vaporous or brilliant, to satisfy all tastes, all the whims of fashion. It is Le Printemps that makes these delicate fantasies blossom,” noted L’Illustration.49 Finally, one of the original Parisian department stores, specializing in men’s attire, was called La Belle Jardinière—The Beautiful Gardener. This store was originally located on the quai aux Fleurs, on the Île de la Cité, next to one of the city’s most important flower markets. Within the store as much as the flower markets nearby, flowers offered consumers not nature per se but rather a carefully crafted spectacle akin to that produced by fashion. “The flower is charming by nature but chic only by fashion,” noted writer Georges Montorgueil in his Croquis parisiens, confirming, indeed, how the social, economic, and cultural categories that governed fashion—including Parisian chic—also informed the production and consumption of flowers.50

While not necessarily expensive, flowers were, and continue to be, objects of conspicuous consumption. They advertise one’s civility and appreciation of beauty for its own sake. It is hardly happenstance, then, that the profusion of flowers in Paris was one of the city’s principal claims to distinction. Indeed, as noted earlier, between 1853 and 1870, Adolphe Alphand and Jean-Pierre Barillet-Deschamps, working under the direction of the prefect of the Seine, the Baron Georges Haussmann, created or redesigned large sections of the city’s public areas, including wooded parks, smaller neighborhood squares, and long promenades. Among these, the Parc Monceau and the Pré Catelan, a pleasure garden in the city’s western Bois de Boulogne, were especially well known for their beautiful flowers. The selection of flowers for the Pré Catelan was particularly extensive; ranging from begonias and roses to azaleas and hibiscus, not to mention the classic ‘Rubens’ geraniums, it bore witness to the evolution of horticulture over the course of the preceding thirty years. Nevertheless, flower beds, Alphand emphasized, need not be composed of many different types of flowers in order to be pleasing to the eye: “In the last couple of years, we have imagined creating corbeilles made of flowers or shrubs of the same species. This method of proceeding is infinitely preferable to the use of differently colored plants, which in the past had been mixed together in plate-bandes and corbeilles. The dispersal caused a sort of confusion; and the flowers with the richest colors, the most remarkable plants, were lost in a mess of shades and shapes that ruined the whole effect.”51 Composed of only one or two types of flowers, the beds often seen in Parisian parks, he insisted, were less costly to produce and maintain and often more eye-catching than more complicated designs. “The beautiful bouquets pop out against the green grass with great vividness,” he observed, reassuring the public that, in the realm of landscape design, pragmatic financial considerations and aesthetic ones were perfectly compatible.52

The flowers planted in the public parks, gardens, and squares throughout Paris were mostly produced at the Jardin fleuriste de la Muette, a cluster of greenhouses located on the avenue d’Eylau. Established in 1855, the Jardin de la Muette was originally created to furnish the Bois de Boulogne with plants and flowers. However, as the number of municipal green spaces increased, so did the size of the establishment. By 1868, the glassed-in greenhouse space reached 6,867 square meters and the nursery produced more than three million plants for the city of Paris every year.53 It was, as Charles Yriarte observed, “a huge factory where we manufacture the flower.”54

The production methods implemented at the Jardin de la Muette contributed to making flowers more widely accessible to Parisians. For some garden experts, however, certain flower arrangements elevated public taste while others debased it. Speaking of the Haussmann-era squares, Émile Zola, for instance, remarked, “I confess that I cordially hate these lawns surrounded by railings where the grass and flowers are on display as if in the window of a shop.”55 The rampant commercialism of the era, he thus suggested, permeated even those rare spaces specifically created as oases from the traffic and excitement of modern life.

The showiness of Parisian green spaces also attracted notice from the English landscape designer Robinson, a fierce opponent of the bedding-out style. Concerning the flower beds on the islands in the Bois de Boulogne, he wrote, for instance, “There is one feature in the Bois de Boulogne which cannot be too strongly condemned—the practice of laying down here and there on some of its freshest sweeps of sloping grass enormous beds containing one kind of flower only. . . . This is done to secure a paltry unnatural and sensational effect, which spoils some of the prettiest spots. Let us hope that some winter’s day, when the great beds are empty, they may be neatly covered with green turf.”56 These flower beds did, indeed, create a powerful chromatic visual effect; this was the express purpose of their design.57 Contrary to Alphand, however, Robinson believed there were considerable risks involved in such an approach. As he explained elsewhere, “In [bedding out and related gardening techniques, such as carpet bedding and mosaiculture] the beautiful forms of flowers are degraded to crude color to make a design, and without reference to the natural forms or beauty of the plants, clipping being freely done to get the carpets or patterns ‘true.’ When these tracery gardens were made, often by people without any knowledge of the plants of a garden, they were found to be difficult to plant; hence attempts to do without the gardener altogether, and get color by the use of broken brick, white sand, and painted stone.”58 In other words, in order to be sustainable, flower gardens needed to be founded on more than the reigning popular taste for color. Persisting in the path laid out by Alphand, which downplayed or disfigured plants’ forms, Robinson warned, would ultimately undermine flowers and gardening altogether.

Starting with the revival of formal flower beds and bedding out, this tendency toward ostentatious display of color and the overlapping of gardening and fashion reached its peak with the development of mosaiculture—a style of gardening that used bedding flowers and colorful, leafy dwarf plants to create figures, words, or abstract ornamental patterns. Popularized in France at the Universal Expositions of 1867 and 1878 and the temporary exhibits of horticultural societies, the style enjoyed widespread appeal (fig. 20). Indeed, in 1881, a journalist writing for the Revue de l’horticulture belge predicted that “soon, there will be no garden, no matter how small, that does not have its little patch of mosaic.”59 However, being an affront to Alphand’s principle of simplicity as well as to Robinson’s plea for more natural-looking flower beds, the style was almost universally condemned by critics, who, in their struggle against popular taste, threw into heightened relief the connection between color, fashion, and the erosion of traditional standards of aesthetic judgment and practices of signification.

FIGURE 20

Mosaiculture butterfly garden featured at the 1878 Universal Exposition, Paris. Revue horticole 50 (1878): 467. Courtesy of the Library of the Gray Herbarium, Harvard University, Cambridge, Mass.

Everything about the style—its overdesigned artificiality, ostentatiousness, and popularity among the general public—smacked of a sort of commercialism that made most tastemakers uncomfortable. Elie-Abel Carrière, writing for the Revue horticole, refused to pronounce himself on the aesthetic merits of mosaiculture, treating it as an aberrant fashion that had to be endured rather than understood. There were, he recognized, some laudable examples of this type of garden. Yet, mosaiculture, he observed, had already won over public opinion and would therefore neither benefit from his approval nor suffer from his criticism: “It is futile to fight fashion! Consequence of a principle, of taste that we cannot grasp, it is beyond reasoning, and all the obstacles we try to put in its way sometimes only serve to make her stronger, to increase [fashion’s] power.”60 Mosaiculture, he thus suggested, obeyed not the principles of art or science but rather the fickle whims of fashion.

In reality, the connection between mosaiculture and fashion was more immediate than even Carrière acknowledged. Jacques Welker, a gardener to Maurice Garfounkel at the Villa Caprice in Auteuil, was a French pioneer in the design and creation of mosaic gardens made of exotic shrubs and flowers. The idea of creating patterns using colorful plants came to him in the early 1860s, he explained, “by seeing the display of a marchand de nouveautés, all the differently colored fabrics folded and folded again on top of one another, producing such a lovely effect that it struck me and I thought: If I could succeed in creating such an arrangement with plants, the effect would also be very lovely.”61 Truthful or not, Welker’s story confirms the connection that existed, at least on a visual level, between the colors of fashion and those visible in the public and private parks and gardens of France during the second half of the nineteenth century. It also explains why critics such as Carrière felt so comfortable dismissing mosaiculture as an arbitrary and irrational fashion.

Artificial Flowers: The Importance of Color and the Meaning of Realism

The desire to make color a central aspect of the garden experience led horticulturalists to push the boundaries of nature. Flowers became mass commodities and increasingly artificial ones at that. They were subject to the ebb and flow of fashion trends and made regular appearances in department stores and fashion magazines. Flowers, however, not only served as a setting for displaying and appreciating fashion but also were part and parcel of women’s attire, namely in the form of artificial flowers. Artificial flowers were ubiquitous in nineteenth-century women’s fashion, reinforcing, more than any previously cited example, the bond between horticulture and fashion. In fact, far from being impermeable to the changes occurring in the world of horticulture as a result of the gradual overlapping of commerce and nature, the business of artificial-flower making raised many of the same questions: What was the relationship between color and fashion? What role did color play in blurring the boundary between the natural and artificial? What was the importance of color in relation to form? And, given the increasing chromatic variety that characterized the modern marketplace, what, if anything, distinguished true beauty from mere fashion? In fact, one may even say that artificial-flower mania exhibited, in heightened form, the trends that shaped French horticulture and gardening in the second half of the nineteenth century.

Attentive as always to the variety and play of colors, Zola recorded in his research notes for Au Bonheur des dames that one department store presented its artificial flowers to shoppers in the form of a striking parterre.62 However, while from retailers’ perspective, artificial flowers were but another colorful commodity alongside fabrics, ceramics, paper goods, and so on, for artificial-flower makers they were a source of livelihood, a tangible manifestation of their labor, and a potential source of pride. The expansion of consumer culture nevertheless posed a serious challenge to traditional ways of working as well as thinking about their work. In particular, artificial-flower makers anxiously debated how best to use color, weighing their clients’ seemingly insatiable taste for novelty against their own aesthetic precepts and commercial priorities.

According to the entries on artificial flowers published in the Encyclopédie of Diderot and d’Alembert, the precise reproduction of nature gradually became a priority for artificial-flower makers in the eighteenth century, thanks to the efforts of two artisans: one known under the name Séguin, active during the first half of the century, and another called Joseph Wenzel, in the second half.63 Not surprisingly, both insisted on the necessity of studying botany for the accurate reproduction of natural flowers. Also important for artificial-flower makers, they explained, was mastering the chemistry of dyeing.64 Indeed, as Séguin and Wenzel saw it, the development of finer dyes, which better replicated the color of natural flowers, was central to their whole enterprise; color was a crucial instrument in the service of artificially reproducing the natural world.

In the nineteenth century, realism continued to be highlighted as a desirable feature and distinguishing characteristic of high-quality artificial flowers in advertisements and professional publications, as well as in the reports of jury members charged with evaluating the exhibits of artificial-flower makers at the Universal Expositions held in Paris at regular intervals. One article underscored, for example, how the Compagnie florale’s factory in the Paris suburb of Rueil included “a well-cultivated garden and greenhouse [that] allow for constant comparisons with nature.”65 Moreover, the factory’s chemist had recently managed “to re-create artificially all the immediate principles of the vegetable kingdom, which will allow the Compagnie florale to offer its clients flowers of such a finish and perfection that they will be able to compete with the brilliance and freshness of nature itself.”66 In another example, jurors for the Universal Expositions repeatedly commented on how artificial flowers of the Compagnie florale and other French manufacturers could easily be, and often were, mistaken for real ones. “The flowers, leaves, herbs and fruits exhibited . . . by Parisian manufacturers arrived at a degree of perfection such that many visitors examining window displays, such as those of Misters Baulant, Delaplace, etc., thought that they were in the presence of nature,” wrote a juror at the 1867 exposition, confirming, more specifically, the superiority of French production.67

Nevertheless, several factors militated against the rule of realism in the artificial-flower industry. Starting in the mid-nineteenth century, artificial flowers became a much more popular fashion accessory, leading to a sharp increase in the number of manufacturers and total value of production. Around 1847, Paris counted only 622 producers, manufacturing about eleven million francs’ worth of artificial flowers. By 1858, the number of producers had doubled, and production value had risen to sixteen million.68 Twenty years later, in 1878, the producers were spread among three thousand establishments, and the value of production attained twenty-five million.69 By the turn of the century, forty thousand Parisians were employed in the industry.70 Coming up with novel designs that would bring women back season after season became more important than ever, accentuating debates about the ambiguous nature of artificial flowers—part science, part art, and part fashion—and the standards that had until then served to evaluate the beauty and quality of the final product.

Next to high-end artificial-flower makers, who dazzled visitors at the Universal Expositions with their ultrarealistic creations, many more manufacturers responded to the challenge of coming up with new designs by creating imaginary flowers that had no equivalent in nature. In 1864, for instance, Arthur Mangin observed, “The head florist is not content with picking the most beautiful, most dazzling or rarest flowers from fields, gardens, and greenhouses, combining them with leaves and fruits from the mother plant, forever altering the composition of bunches, bouquets, and wreaths. With the assistance of only her imagination and artistic talent, she resolves problems that would debunk the science of the most consummate horticulturalist. She makes blue or variegated roses, pink violas, and yellow violets. What’s more, she creates ravishing flowers for which we would search in vain on all the five continents of the world.”71 Mangin’s account is confirmed by Julien Turgan, who noted that highly realistic flowers were generally the preserve of a few elite firms, while the bulk of flower makers supplied the market with less costly, highly fashionable goods that were simultaneously artificial and fantastical:

Of course, the exact imitation of flowers, and especially pretty ones, is an art, but it could not by itself sustain such a vibrant industry. The basis of the industry is certainly the reproduction of real flowers, but the imagination of the manufacturer or worker has endlessly multiplied the sizes, the dispositions, the assembly, and thus creates a whole imaginary flora [une flore de fantaisie] that can, thanks to its infinite variety, respond to the every whim of fashion.

What distinguishes, in our opinion, the art of ornamentation proper from Academic art is that the former is not at all obliged to accurately copy the object that serves as model; in certain cases even, we find that the design benefits from distancing itself from nature. . . . Also, as soon as fashion gets tired of real flowers, sometimes big, sometimes small, she moves quickly toward, for example today, bronzed leaves, golden fruits, and chimerical flowers created by the imagination.72

Indeed, as with realistic flowers, color also played an important role in fleurs de fantaisie.

But whereas flower makers working in the style known as le naturel employed color in the service of better replicating nature, flower makers specializing in fleurs de fantaisie focused on creating flowers that were fashionable and eye-catching, owing to either their novelty or their sheer brightness. Examples of nineteenth-century fleurs de fantaisie described, for instance, in advertisements and how-to instruction manuals for professionals and hobbyists all suggest that the most common and presumably most appreciated type of artificial flower was that which more or less replicated the form of a real flower but substituted its natural color for an imaginary one: “[Certain] imaginary flowers differ from nature only by their color: thus, we make lilacs, roses, and daisies sky blue; white grenades, pink tuberoses, etc.; this is what is most common” (fig. 21).73

FIGURE 21

Women’s toque with blue cornflowers, ca. 1890–99. Musée des arts décoratifs, Paris.

Thus, alongside nurserymen’s, florists’, landscape artists’, and gardeners’ efforts to heighten the chromatic appeal of natural flowers, artificial-flower makers also invested heavily in color. A journalist writing for Le Figaro drew an explicit connection between these parallel developments:

Surely you have admired the splendid plants with variously colored leaves that gardeners recently introduced into France and that, [originally seen] on lawns and in gardens, can now be found in living-room jardinieres.

Never has nature more forcefully demonstrated its power than with these combinations of colors and exquisite shades, you said to yourself.

Well! Translated into the realm of human arts, the challenge has just been overcome; the honor goes to the Compagnie florale, which had already accustomed admirers to many surprises but this time has even surpassed itself.74

Conversely, in his criticism of the new squares scattered through the city, Zola suggested that Parisians “seem to believe that trees are made of tinplate and that the flowers that make up the borders come from a milliner.” Furthermore, “they live on happily in this belief,” the author quipped.75 In other words, as flower makers took on the challenge of producing colorful exotics and hybrid flowers that appeared in public green spaces, these, in turn, were imagined by Parisians as artificial, imaginary creations akin to those that adorned women’s hats.

Among elite flower makers, however, the distinction between imaginary and real flowers remained no less firmly entrenched. For instance, it was customary for flower makers to insist that, whatever the pressures imposed on manufacturers by the fashion industry, there was simply no need to create fleurs de fantaisie. Nature, they insisted, supplied flower makers with an ample number of real flowers to copy; creating something new revealed neither intelligence nor creativity but a mere lack of effort. In 1843, L’Iris, an early trade journal, pointed out, “The competition, which is now so intense, forces manufacturers to change their models frequently, and since they do not have pretty flowers at their disposal, they are forced to invent and move further and further away from nature, which they accuse of being parsimonious, without thinking that they are speaking blasphemy, that nature is inexhaustible, and that she only asks to be studied.”76 While acknowledging the pressures exerted by fashion on flower makers to find new models each and every season, the author nevertheless believed that le naturel was the only acceptable answer to the irrational rule of fashion: “There is an important goal to attain, a brilliant victory to win: we have to succeed in directing the taste of fashion, we have to guide the whims and eccentricities of this despotic sovereign. . . . We have to prove that only in the imitation of nature lies the great art of flower making and that all other innovations that do not exist are always inferior to the pure and scrupulous imitation of a model taken from nature.”77 Realism, in other words, was not only an aesthetic preference but also a rallying cry. The article urged flower makers to set the terms of their participation in the industry—to master fashion rather than simply be subjected to it.

This negative view of fleurs de fantaisie persisted in the second half of the nineteenth century. Despite rising market pressures and the increasing artificiality of natural flowers, elite flower makers continued to actively resist the rise of fleurs de fantaisie and the chromatic free-for-all associated with this type of production. The reason for this is not hard to understand. As Mangin explained, “However fertile and brilliant her imagination, an artist’s real talent always resides in the ability to faithfully copy the fruits of nature. And that is to what flower makers, who aspire to a solid reputation [and] well-deserved success, apply themselves.”78 The making of artificial flowers was a labor-intensive process, involving several steps: découpage (cutting the various flower pieces, such as leaves and petals), trempage (dyeing), gauffrage (shaping the petals), assemblage (assembling the petals to form the flower, the longest and most delicate step), and montage (combining the flower with the stem and leaves). In this context, realism became the visual measure of skill and allowed the flower maker to ask a high price for her labor. In other words, in promoting le naturel over fleurs de fantaisie, elite flower makers were fighting to preserve a special status for artificial flowers distinct from, and superior to, mere fashion.

For elite flower makers, imaginary color represented one of the most significant threats to the scientific and aesthetic legitimacy of their industry and the higher salaries earned by those who participated in it. High-end fleurs de fantaisie, such as those exhibited by the Maison Frantzen at the Union central des beaux-arts appliqués à l’industrie in 1874, whose “imaginary shades do not at all pretend to copy nature,” were not completely unheard of.79 But some evidence also suggests that color became increasingly important in the design of artificial flowers as firms strove to satisfy the demands of a mass market with inexpensive, quickly made goods. Starting in the 1830s and 1840s, producers implemented a strict division of labor; workers often specialized in only one type of flower or task, such as gauffrage, assemblage, or montage. By making color more important than form, manufacturers reduced the time, skill, and money required to make artificial flowers. Indeed, following the invention and successful commercialization of synthetic dyes in the late 1850s, bright hues were forever more widely and cheaply available.80 Labor costs, in contrast, evolved in the opposite direction. It was hardly happenstance, then, that many flower makers believed that there was, as one instructional manual put it, simply no salvation outside le naturel, whether in the form of bona fide fleurs de fantaisie or flowers so poorly made that they simply failed to meet the standards of realism. Realistic flowers, Clélie Sourdon wrote, “have a worth beyond any value, that is to say that we can sell them at a high price, since in this case it is not the supplies composing the materials that we pay for, it is the work, it is the artist’s talent.”81 The making of high-quality artificial flowers, the author thus insisted, involved more than a good eye for color.

Blue Roses, Yellow Violets, and the Practice of Plein Air Painting

The Impressionists produced many paintings of flowers and gardens, and some were passionate gardeners themselves, Claude Monet and Gustave Caillebotte in particular. In fact, these two artists, who otherwise had very little in common, stayed in close contact long after the last Impressionist exhibition in 1886, largely for the purpose of exchanging plants, gardening advice, and the latest horticultural news from France and abroad. On May 12, 1890, from his famed garden in Giverny, Monet wrote to Caillebotte to assure him that he had “received the dahlias safely.”82 Later, he urged his friend “to come on Monday as arranged, all my irises will be in flower, later they will have faded.”83 Monet’s letters also sometimes turned to horticultural novelties, seen at an exhibition or acquired for his garden from some specialized purveyor: “I have seen the exhibition of flowers in Paris, wonderful things. I met your friend Godefroy there. Can you tell me where I can buy annuals? I have seen superb things at the exhibition, but it was too late to sow them, among other chrysanthemums . . . and Layias with yellow flowers, perhaps you would have some yourself, anyhow try to make enquiries.”84 In comparison with Monet, Caillebotte’s tastes tended toward the exotic and expensive, including rare species of roses and orchids, which he cultivated in greenhouses on his property in Petit-Gennevilliers.85

Art historians have been quick to point out how, for Monet, Caillebotte, and other Impressionist artists, the garden served as a privileged place to experiment with form and, especially, color.86 Still, relying on traditional narratives about the practices of plein air painting and artists’ desire to depict the fugitive effects of light and color, these studies generally understand gardens as little more than well-curated patches of nature and flowers as neutral pretexts for formal innovation. Indeed, even studies that acknowledge the large amount of work that artists completed indoors—away from the original motif and the full spectrum of modern horticultural and gardening practices, from hybridization to bedding out—persist in emphasizing the Impressionist artist’s exceptional eye and touch, his unique interpretation of the physical and psychological qualities of the garden’s colors.87

The Impressionists themselves did much to encourage this view. Monet estimated, for instance, that his greatest merit was “to have painted directly from nature with the aim of conveying my impressions in front of the most fugitive effects.”88 As this chapter demonstrates, however, the artist’s depictions of his garden in Giverny, widely recognized as harbingers of twentieth-century abstraction (fig. 22), stand at the tail end of a much broader transformation of floriculture through color and commerce—one that repeatedly and forcefully challenged dominant understandings of the proper relationship between the natural and the artificial, the real and the imaginary, not to mention color and form.

FIGURE 22

Claude Monet, The Artist’s Garden at Giverny, 1902. Oil on canvas. Öesterreichische Galerie Belvedere, Vienna.

The intersections between Impressionism and this broader transformation of visual and material culture are not difficult to find. In 1892–93, Monet worked on his series of paintings of the Rouen Cathedral, which famously captured the changing appearance of the building at different times of day and year, from at least two different magasins de nouveautés, that is to say, while surrounded by fashionable textiles, garments, hats, and other accessories.89 His interpretation of the colors produced by sunlight reflecting on the cathedral originated, geographically if not causally, in the world of fashion. Direct influence between French artistic modernism and French floriculture—or fashion—is not, however, what most concerns me here. More important to our understanding of the history of modern visual culture is that artists, manufacturers, and consumers of the goods and images they produced shared a common basis from which to reimagine color, its relationship to form, and modes of signification.

In fact, while Monet continued his bold experiments with color in Giverny, an artificial-flower maker interviewed for a government-sponsored study, published in 1913, described a parallel development in her sphere of expertise: color had become the deciding factor in the manufacturing and marketing of artificial flowers. “In the past,” she explained, “we used to take care over the slightest details; then, the work could stand up to examination.”90 But because of the extreme division of labor, many flower makers no longer had any understanding of color: “In many establishments the apprentice never touches dye, and for me that is the essential part. Dye is for us what fitting and cut are for a seamstress.”91 In short, for this flower maker, color was the form—the equivalent of fitting and cutting for seamstresses.

This new way of seeing the art and business of artificial-flower making was opposed by most high-end artificial-flower makers in the late nineteenth century, who believed that the reproduction of natural flowers, as precisely as possible, was key to maintaining their livelihoods and professional reputations. Yet, as evidenced by the early twentieth-century testimony collected by the Ministry of Labor, the pressures of the fashion industry, increasingly geared toward mass production and novelty, pushed flower makers in another direction, that of cheap, unapologetically artificial, and eye-catching color. In the end, Georges Montorgueil probably summarized the situation best: “Vegetation rarely comes to town without freshening up. The city dweller likes nature, but not [when it is] too natural. He accepts that, to accentuate their waist, we put on camellias, like women with that name, corsets made of iron wire, and that, once in a while, for the sake of change, there are green bluebonnets and blue roses.”92 Indeed, whereas in the minds of artists and poets of the Romantic era blue roses symbolized the pure and unattainable ideal, in the arena of women’s fashion analyzed here they were a telling emblem of the fantastical nature of modern capitalist societies.

Highlighting how the heightened chromatic vivacity and variety of nineteenth-century France undermined traditional standards of judgment and practices of signification, floriculture provides a particular and precious window onto the development of modern visuality. In the case of natural flowers, horticulturalists’ and plant breeders’ taste for color led them to blur the distinction between the natural and the artificial through the creation of hybrid varieties. These flowers were then displayed in eye-catching flower beds or kiosks, sometimes according to the laws of color harmony originally expounded by Chevreul but, more often, according to the dominant fashion of the day. Meanwhile, the spread of composite-style ornamental gardens and mosaiculture marked a clear departure from the nature-inspired English landscape garden toward the ostentatious display of color for its own sake. Flowers did not represent a natural realm, untouched by the rule of fashion. Instead, as in the fashion industry, where the quest for color led to the development of synthetic dyes, the search for chromatic novelty and variety in floriculture led to the creation of flowers that resembled less and less anything found in nature.

The greater variety of natural flowers available in the marketplace lent credence to artificial-flower makers’ claims that there was no need to create imaginary flowers to satisfy the public’s taste for novelty. For these elite flower makers, color was to be used solely for reproducing nature as realistically as possible. In any case, faced with the challenge of developing new models as well as the need to cut production costs, many flower makers found themselves making fleurs de fantaisie that had no parallel in nature. A reasonably priced flower in a beautiful, eye-catching color was more likely to find clients, regardless of whether it was a faithful reproduction of nature, which was, of course, itself in the process of being transformed by color and becoming more artificial.

In short, what makes floriculture a particularly telling chapter in the history of modern visual culture is the way it reveals, in concrete, material terms, how the growing importance of color in nineteenth-century consumer culture challenged traditional categories of visual perception and understanding. The economic motivations behind horticulturalists’, plant breeders’, gardeners’, florists’, and artificial-flower makers’ pursuit of color do not make the aesthetic dimension of this transformation any less real, nor can this transformation be understood in economic terms alone. The proliferation of color in the department store, on the streets, and in the garden redefined traditional understandings of the proper relationship between color and form, according to which the latter was rigorously subordinate to the former.

The previous chapter revealed how Chevreul promoted a radically optical and abstract definition of color, including in contexts such as fashion, which many tastemakers believed needed to incorporate expressive or symbolic modes of signification. The same could be said about Chevreul’s take on gardens. Ignoring folkloric meanings attached to flowers, he viewed them almost exclusively from the perspective of color, which he interpreted in strictly optical terms. However, for elites of the gardening world, such as Robinson and Carrière, the proper use of color in gardens was determined not by science per se but by what they imagined to be the eternal laws of beauty. Artifice was admitted, but only up to a point. For elite flower makers the absence of explicit artifice was practically all that mattered. The meaning and status of color were determined first and foremost by its relationship to actual flowers, whether natural or artificial. Flower makers’ authority in the marketplace hinged, in other words, on color’s referentiality.

In contrast, for the producers and consumers of colorful goods, meaning was constructed not only through science, the eternal laws of beauty, or nature but also through the visual appeal of novelty and fashion. New hybrid varieties, gardening trends that heightened the colors of flowers through clever juxtapositions, and artificial flowers played an especially important role in highlighting the tenuous distinctions that separated the natural from the artificial, the real from the imaginary. From blue roses to yellow violets, the increasing confusion between these categories defined modern visual forms and guided Parisians’ investment in nature, art, and the emergent capitalist economy of goods and mass entertainment.