Posters, Trade Cards, and the Politics of Ephemera Collecting in Fin-de-Siècle France |

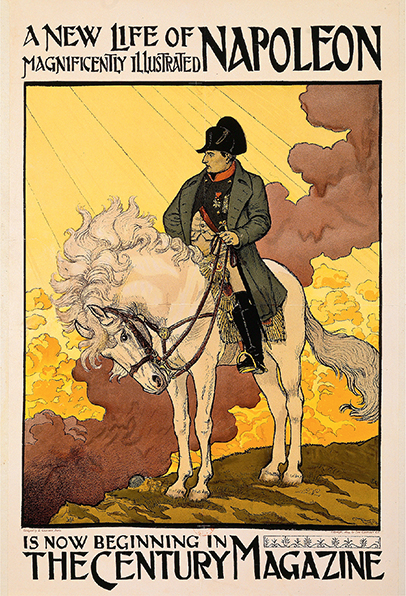

As manifestations of the French capital’s buoyant commercial culture and dynamic street life, the large color posters designed by Jules Chéret, Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec, and a coterie of other innovative commercial artists working in the 1880s and 1890s count among the most iconic symbols of fin-de-siècle Paris (figs. 68 and 69).1 There are several reasons for this, not least the sheer ubiquity of posters in the urban landscape. Posted on the sides of buildings, construction partitions, public urinals, and omnibuses, inside of train stations, and on specially designed columns and kiosks throughout the city, these large full-color advertisements had an inescapable, insistent presence that could easily provoke hyperbole or parody (fig. 70). As one journalist noted, writing under the pen name Maurice Talmeyr, “The real architecture today, the one that grows from the living and pulsating environment, is the poster, the proliferation of colors under which disappears the stone monument, like ruins overtaken by nature. It is the temporary edifice demolished every night and reconstructed every morning, made of tawdry and changing images that annoy and cry out to the passerby, that pander, provoke, laugh, guide, and accost him.”2

FIGURE 68

Jules Chéret, Bal du Moulin Rouge, 1889. Département des Estampes et de la photographie, Bibliothèque nationale de France, Paris.

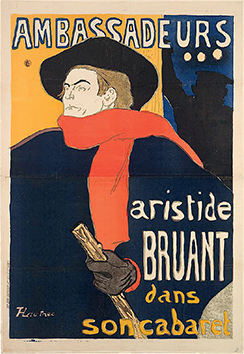

FIGURE 69

Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec, Ambassadeurs: Aristide Bruant, ca. 1892. Smith College Museum of Art, Northampton, Mass. Courtesy of the Smith College Museum of Art, Northampton, Mass.

FIGURE 70

Eugène Atget, Rue de l’Abbaye, Saint-Germain-des-Prés, 1898–1900. Photograph. Département des Estampes et de la photographie, Bibliothèque nationale de France, Paris.

In election years, entire buildings—entire sections of the city, according to some—were wallpapered in posters. “Paris belongs to posters. Lists take over walls and partition-politics [politique pariétaire] puts itself on display at the corners of intersections, with multicolor declarations of faith. Shall we never hear about anything else than elections! It’s the big thing right now, and a little bit also that of our future, [since] a part of our destinies lies in these pieces of paper with which we are presently decorating our walls,” Jules Claretie observed in La Vie à Paris, evidently conflicted over the fact that something as significant as the country’s political future could depend on such a bizarre ritual involving paper and glue.3 For others, walls covered in a collage of loud colors and disparate shapes was a more straightforwardly positive development. For Eduard Van Biema, writing in La Nouvelle Revue, the spectacle was both aesthetically and morally inspiring: “By virtue of duly registered notarial contracts, the virgin surfaces of walls transform themselves into polychromatic pictures where the most diverse industries and professions meet and where manufacturers of eye-glasses, hernial medical supplies, chocolate makers, as well as insurance companies get along and extend their hands to one another in fraternal harmony.”4 Posters, especially those carefully selected and assembled by advertising agencies, provided a powerful example of a primary political value of the French Republic, Van Biema thus suggested.

In addition to standing in for modern Paris’s architecture and sociopolitical makeup, posters were powerful testimonies to the modern experience of color. Indeed, as we shall see in this chapter, despite posters’ distinctly capitalist, bourgeois origins, it became increasingly common for the cultural elite of fin-de-siècle France, from artists and art critics to novelists and politicians, to think about color through posters and vice versa, with important consequences for the status and meaning of both. Situating posters within the wider context of nineteenth-century mass-produced color imagery, from the first full-color lithographic reproductions of paintings by Old Masters to trade cards, this chapter explains and analyzes how posters were raised above the colorful bazaar that was nineteenth-century print culture. It argues that posters were distinctive not so much for their inherent aesthetic qualities, broad democratic reach, or innovative design, as for the consideration they received from the French cultural elite, which until then had scoffed at color in its modern commercial forms.

In elevating the poster above other disposable colorful prints produced by lithographers, collectors and critics set the terms by which it became acceptable for bourgeois men to take pleasure in color, including in its most overtly mass-produced and -reproduced commercial varieties. No longer strictly associated with the counterfeit, the primitive, the feminine, the foreign, or the degenerate, color was massively reinvented and redefined in the fin de siècle. As exemplified in the critical writing about Jules Chéret, the commercial artist widely credited with starting the artistic poster trend, color was transformed into something simple, necessary, and distinctly French. Instead of deceitful, posters’ colors, critics explained, honestly reflected the mechanical methods by which they were produced. Posters did not attempt to seduce viewers with subtle hues, but proudly touted their yellows, blues, and reds, no longer trying to replicate the visual effects of another medium or any recognizable reality at all. Indeed, when discussing Chéret’s posters, critics regularly insisted on the irrelevance of the product advertised and figuration more generally, focusing instead on the image’s formal aspects. Metaphors of prismatic light and, especially, new psycho-physiological understandings of color became dominant themes in elite critical discourse on posters, displacing earlier, less positive associations between color and chemistry.

Existing scholarship on posters has developed largely independently of writing on other forms of commercial chromolithographic prints.5 Consequently, many of the arguments advanced by poster enthusiasts—namely surrounding posters’ unique aesthetic qualities, their distinctly French character, and their role in diffusing art among the masses—have remained inadequately interrogated. How did poster criticism and collecting practices influence late nineteenth-century conceptions of color? What do they reveal about commercial print culture and, just as importantly, what do they conceal?

By virtue of being displayed on the streets, posters made the visual pleasures and practices associated with color available to all members of society, prompting Republican and left-leaning critics, from Roger Marx to Gustave Kahn, to insist on the inherent egalitarianism of posters. Their bright, flat colors stood in opposition to bourgeois materialism and the conservatism of the Salon, thus constituting, the more radical proponents believed, a powerful countermodel for politically engaged socialist art. Still, there was nothing necessary or predictable about the successful elevation of posters to the status of fine art. Posters originated from the very same print shops—indeed, the very same mechanical printing presses—that produced labels, trade cards, religious imagery, and calendars. And artists lauded for their poster designs often applied their skills to these other, less privileged types of commercial ephemera. Finally, most critics’ claims for the uniqueness and inherent superiority of posters’ colors quickly fall apart upon closer inspection of the images. Analyzing the striking novelty of critics’ arguments that mass-produced advertisements should be granted the status of art, what follows reveals the social, economic, and political mechanisms by which the cultural elite briefly attempted to redefine the color revolution in its own image.

Color in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction: A Brief History of Chromolithography

The public discourse that fueled the ascension of posters to the realm of fashionable collector’s item was remarkably consistent on certain points, most notably its insistence that posters were an absolutely novel art, bearing no relation to earlier forms of chromolithography. “It is marvelous to see their watercolors or pastels, beautifully reproduced at vertiginous speed of the machinery, giving voice to something other than half-forgotten antiquities,” commented print curator Henri Bouchot, drawing a parallel between the modernity of the presses and the stylistic novelty of the images produced by Chéret and his “numerous imitators.”6 Indeed, according to poster enthusiast André Mellerio, Chéret’s designs marked a definite rupture with the “old and banal chromolithography” of yesteryear.7 Posters were a wholly new art form, these critics insisted, and much more than simply larger versions of the reproductive color prints with which everyone was already familiar.

German printer Aloys Senefelder, the celebrated inventor of lithography in its standard black-and-white form, is also credited with having produced the first color lithographs, using a process he referred to simply as Farbendruck (color printing) in his 1818 publication A Complete Course of Lithography.8 As opposed to intaglio printing techniques, such as engraving or etching, which demanded that the artist incise his or her image into wood or metal, lithography, Senefelder explained, was a form of “chemical printing”—the basic principles of which remain very much the same today. In its simplest form, the printing process begins with the artist drawing on a polished lithographic stone using a greasy crayon. After the drawing is completed, the artist or printer wets the stone with water. Next, the stone is entirely covered with a grease-based ink. Since water and oil repel each other, the ink remains only on the surfaces previously marked by the artist with the greasy crayon. Senefelder discovered that, by treating the stone with gum arabic, it was possible to further delineate the inked surfaces from those meant to remain blank. Combined with nitric acid, the gum arabic fixes to the nongreased areas, preventing any ink from binding to the stone; whereas on the greased areas, the gum arabic helps the ink bind even more tightly to the stone. The same basic approach, Senefelder realized, could easily be employed using colored inks, provided that the chemicals in the inks did not react with those used in the printing process. Indeed, the first Farbdrucke were closely aligned with their black-and-white forerunners.

By the 1820s, Senefelder and a few other lithographers were already producing multicolored images. These types of images remained extremely rare, however, because of the skill required for the proper combination and juxtaposition of colors, a process known as color registration. Looking back on these early attempts to create coherent full-color images, lithographer Jean Engelmann noted, “Thanks to their exceptional manual dexterity, a few printers succeeded some way or the other in registering a couple of colors. These proofs, which were obtained always with great difficulty, slowly, and not without considerable waste, exhibited only approximate color registration and represented what one might call tours de force, meant to be classified among lithographic curiosities rather than industrial products.”9

In 1837, Jean and his father, Godefroy Engelmann, patented a frame—more accurately, a chase—that greatly facilitated color registration by locking the lithographic stone and paper firmly into place for the duration of the multistep printing process. “Mr. Engelmann has presented an entirely new principle,” Gaultier de Claubry enthusiastically reported, “with respect to the principles on which [color printing] is founded and with which the pulling of prints is absolutely without difficulty, does not require any knowledge or practice from the worker, is capable of yielding copies that are always similar to themselves and whose effects the draftsman can himself freely determine by the way he executes the drawing.” Moreover, this new technique, “to which [Engelmann] has given the name chromolithography,” de Claubry wrote, was capable of reproducing everything from detailed landscapes to labels, all for much less than it cost to produce color engravings.10

Following in the footsteps of Godefroy Engelmann, who included a reproduction of a portrait by Jean-Baptiste Greuze and of Sir Thomas Lawrence’s popular Master Lambton painting in his inaugural treatise on the new process, French printers quickly began employing chromolithography to reproduce artworks (figs. 71 and 72). In the 1850s and 1860s, for example, printers Hangard-Maugé and Lemercier made an impressive number of high-quality reproductions of artworks, including several for the Arundel Society, an English publisher founded in 1848 with the express mission of “populariz[ing] high art among people who have everything to learn and gain experience.”11 As for Engelmann, the firm’s most impressive accomplishments in the distinguished area of fine-arts reproduction were a series of prints depicting the medieval mural paintings of the Church of Saint-Savin, published in 1845 (fig. 73). The plates, Henri Bouchot later recalled, “were for France what Owen Jones’s Alhambra had been for England, a solid starting point, which could serve as a model for undertakings attempted at a later date.”12

FIGURE 71

Portrait After Greuze, in Godefroy Engelmann, Album chromolithographique, ou Recueil d’essais du nouveau procédé d’impression lithographique en couleurs (Mulhouse: by the author, 1837). British Museum, London. Courtesy of the British Museum, London.

FIGURE 72

Master Lambton (after Thomas Lawrence), in Godefroy Engelmann, Album chromolithographique, ou Recueil d’essais du nouveau procédé d’impression lithographique en couleurs (Mulhouse: by the author, 1837). British Museum, London. Courtesy of the British Museum, London.

FIGURE 73

Eugène-Emmanuel Viollet-le-Duc, frontispiece in Prosper Mérimée, Peintures de l’église de Saint Savin (Paris: Imprimerie royale, 1845). Département des Estampes et de la photographie, Bibliothèque nationale de France, Paris.

These fine-arts reproductions played an important role in the promotion of chromolithography as a new technology. Difficult and expensive to produce, they were regularly featured at Universal Expositions, where they functioned as a standard measure of printers’ skill. Armand Audiganne, secretary of the commission responsible for the 1855 Universal Exposition, reported,

The Universal Exposition contained some truly admirable examples of lithographic prints. Held in place as if under some sort of spell, one stopped for a long time in front of the frames by M. Lemercier, Auguste Bry, Engelmann & Graff [sic], Bertauts, etc. Chromolithography or color printing by means of the lithographic press has succeeded in producing marvelous effects. . . . Who has not seen those plants, stained-glass windows, coats of arms, medieval paintings, etc.? The admirably dosed shades seem to have fallen from the most delicate brush.13

As Audiganne’s remarks attest, full-color reproductions of paintings and other artworks naturally prompted viewers to compare the results printers were able to obtain to the original source. In fact, at the 1855 exposition, more than simply suggesting the possibility, the imperial printer of Vienna expressly invited visitors to view original still-life paintings and chromolithographic reproductions side by side and gauge the realism of the prints with their own eyes.14

The placement of the two images side by side did more than facilitate the comparison of forms, textures, and hues, however. In addition to delighting visitors with their realism, full-color reproductions of artworks added an allure of prestige to chromolithography not afforded by other types of prints. Indeed, in much the same way that photographers anxious to have their medium recognized by others as a legitimate art form often imitated the subjects and forms of painting, lithographers who aspired to a more elevated cultural status sought to ally themselves with the fine arts, painting in particular. To this end, mid-nineteenth-century lithographers used a variety of materials and techniques, including, for example, heavy oil-based inks that closely simulated the texture of paint and glossy varnishes. Sometimes stretched onto canvas and framed, these highly detailed reproductions, known as oleographs, clearly aimed at providing viewers with as close a substitute as possible for the visual experience of standing in front of an original artwork (fig. 74).15

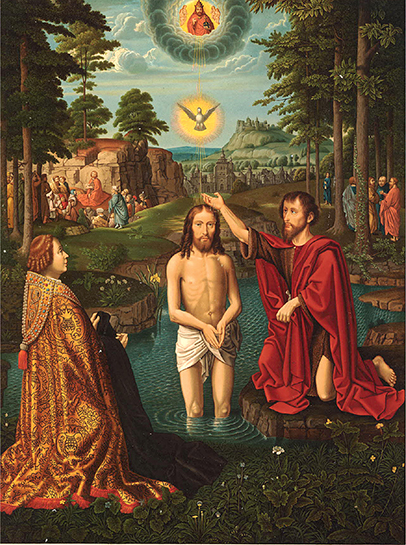

FIGURE 74

Franz Kellerhoven, The Baptism of Christ (After Gerard David), printed by Lemercier & cie, ca. 1854. Oleograph. British Museum, London. Courtesy of the British Museum, London.

As Peter Marzio argued more than forty years ago, these images played an essential role in the democratization of art among the middle classes in the United States.16 This was no less true in Europe, including France. There, editor Léon Curmer adeptly used chromolithography in high-quality art historical publications such as L’Imitation de Jésus-Christ (1855–57), Le Livre d’heures de la Reine Anne de Bretagne (1861), and L’Oeuvre de Jean Fouquet (1866–1867). “The application of the chromolithographic process to the illustration of books,” noted Les Beaux-Arts in 1863, “is a fact that most members of the public, even the enlightened ones, have still not fully assimilated. Thanks to Mr. Curmer, it has opened the doors to public and private libraries and delighted our eyes with [images of the] past filled with intellectual riches, victoriously countering the assertions of sulking spirits, who condemned the arts to a long death.”17 Very early on, printers and critics promoted the idea that chromolithography would serve, like photography, as a helpful handmaiden to the fine and industrial arts as well as the emerging disciplines of archaeology and art history.

As time progressed, however, the enthusiasm of early observers for the finesse and utility of chromolithographic reproductions waned, gradually giving way to widespread condemnation. In some respects, the debate itself took on the aspect of a reproduction, more specifically a reproduction of the still-ongoing argument among members of the cultural elite about the role and status of photography. Indeed, as we know, several key figures active in the mid-nineteenth-century art scene objected that photography was too mechanical a medium to convey anything more than the superficial surface appearance of things. Charles Blanc, Charles Baudelaire, Henri Delaborde, and John Ruskin were among the vocal minority of critics and artists who objected to the photographic reproduction of art for this reason.18 Critics of chromolithography voiced similar concerns. For example, the 1878 Dictionnaire de l’Académie des Beaux-Arts objected that “chromolithography only has the power and the right to imitate the most superficial aspect of the hand’s actions, the least subtle aspect of art. Whatever the past and future perfections of the technology, they will not—they cannot—change the basic principle and true object of the operations; they will never so thoroughly transform the functions of the mechanism as to ever enable it to rob art of its privileges and supplement, with superficial imitations, with a relatively speedy output, the reasoned expression of sentiment.”19 Cheap mechanical forgeries, in their essence as well as final appearance, chromolithographers’ reproductions of paintings were more likely to debase public taste than elevate it, the dictionary suggested.

The mediocrity of “artistic chromolithographs” was a recurrent theme in 1890s criticism. Much like Academic painting, full-color reproductions of paintings were almost universally condemned as hopelessly naïve technophilic enterprises. The prints, critics insisted, were too garish and crude. However laboriously printers tried to hide it, the images inescapably disclosed their mechanical origins—real art could not be faked. In distinct opposition to Les Beaux-Arts’ enthusiastic review of Curmer’s early art historical publications, Bouchot noted of the editor’s Les Oeuvres de Jean Fouquet, “[The printer] did what was humanly possible to do at the time, his work is admirable, but Fouquet is too haughty a genius to let himself ever be surprised. It is his entire soul that we snatch from him, his sensibility [fleur] that we waste with gimmicky print runs and colorings; what remains of him is the work’s skeleton; life has left, and we can no better understand him from these things than we can intimate the subtleties and undertones of the Mona Lisa from the burin of the best engraver.”20

This reevaluation of the earlier days of chromolithography is significant in several respects. Most obviously, perhaps, it highlights how standards of realism are always historically and culturally contingent; the elaborate full-color reproductions of artworks that so impressed critics in the 1850s and 1860s no longer met experts’ expectations in the 1890s—just as color photographs of the 1950s and 1960s fail to conform to the visual understanding of what constitutes a realistic image today.21 That said, it is unlikely that any reproduction, no matter how realistic, would have met critics’ standards. For, indeed, Bouchot and other reformers involved in the artistic poster movement, such as Roger Marx and André Mellerio, objected not simply to specific chromolithographic reproductions of paintings but rather to reproductive printmaking per se. Along with inexpensive poorly made copies of ancien régime furniture, reproductions of paintings, especially the framed and varnished kind, struck these critics as tacky and uncouthly middle class. Oleographs, in short, exemplified everything that was wrong with the modern industrial era.

In emerging avant-garde circles concerned with the renewal of French decorative arts, fake luxury earned special opprobrium. Sculptor Henri Nocq commented in 1896, in response to an exhibition of objets d’art at the Salon du Champ de Mars,

The day when industrialists will have to renounce copies and molds of copies [surmoulages], or see the public forget about their stores, [and] create original models, they will have to sacrifice money, and that’s where it really hurts. The fear of a dip in profits, however slight, makes them wish for the ancient style [la mode archéologique] to last for as long as possible, and unconsciously they come to see as fierce enemies the artists who look for novelty, writers who encourage research, the men to whom they should be asking for help, and who would help them break free from their prejudices and their routines.22

Influenced, in part, by the ideas of architect and theorist Eugène-Emmanuel Viollet-le-Duc, a growing number of avant-garde artists, artisans, and critics insisted that an object’s or image’s appearance should match its function, materials, and mode of production.23 Reproductions of paintings, critics insisted, failed on all three fronts. Used as a foil to highlight posters’ originality, reproductions of paintings had, according to these critics, no place in the new aesthetic order.24

In keeping with this new idea that aesthetic evaluations should be based on whether or not the artwork’s final appearance truthfully revealed the method and materials used to produce it, some critics proposed that it was not chromolithography per se that was the problem but rather its inappropriate application. Indeed, even chromolithography’s fiercest critics sometimes recognized that the medium could be put to good use. The Dictionnaire de l’Académie des Beaux-Arts, for instance, insisted that “by imitating models appropriate to its resources, [chromolithography] will provide services all the more important as they seem less like feats of ambition and, far from aiming at commentary or picturesque development, stick closely to the modest terms of the contract.”25 The Dictionnaire begged the question, however, of exactly what genre, style, or format stuck “closely to the terms of the contract.” What were color lithographs meant to look like, if not paintings or watercolors? Failing to answer the question, the authors of the entry perpetuated through their silence the erroneous notion that chromolithography would only and always aspire to something beyond its reach.

In reality, fine-art reproductions represented only a small portion of nineteenth-century lithographers’ overall production. As Jean Engelmann explained, “It didn’t take long before specialities were established. One establishment dedicated itself principally to picturesque plates, another one picked topographical maps, a third one, labels and analogous work; this one, packaging and novelty papers, this other one, natural history, religious imagery, etc., etc.”26 Regarding his company, more specifically, he explained that “our tastes and interests brought us to devote ourselves principally to archaeological works.”27 In fact, according to business records dating from the 1850s, far from limiting themselves to archaeological subjects, Engelmann & Graf also printed labels, sample cards (cartes d’échantillon), and a host of other colorful paper products (fig. 75). A short time thereafter, the company added diaphanies to its inventory. Imitating the effect of stained glass, “these transparent proofs,” or window transparencies, the printer reported, “bestow an effect that has a very particular charm. They have been warmly received by the public and for several years half of our presses have been taken over by diaphanies” (fig. 76).28

FIGURE 75

Label printed by Godefroy Engelmann’s firm, ca. 1850. 19TT 2G, Société Godefroy Engelmann, Mulhouse City Archives, Mulhouse, France.

FIGURE 76

R. Engelmann, Diaphanie: Catalogue de feuilles (n.p.: R. Engelmann firm, 1876). Canadian Center for Architecture, Montreal. Courtesy of the Canadian Center for Architecture, Montreal. The actual diaphanie would, of course, have been in color.

Starting in the 1860s, new mechanical presses dramatically expanded chromolithography’s range beyond even this, marking a major turning point in the history of the mechanical reproduction of color. “Soon, we’ll see chromolithography take on works that until now escaped it because of the high cost of labor. Its domain enlarges itself endlessly and the future is still full of promise for her,” Jean Engelmann remarked.29 Indeed, originally powered by steam and later electricity, mechanical presses considerably reduced printers’ production costs, eventually making it possible to extend the reach of color to disposable printed works, such as posters, calendars, trade cards, greeting cards, and scraps, to name only a few. By the mid-1880s, these new inexpensive products constituted an important part of lithographers’ revenue. Indeed, as Albert Achaintre attested in 1883, “Religious imagery, popular prints, decorated paper used in deluxe packaging, decals employed to decorate inexpensive porcelain [décalcomanie], the luxury envelope intended for perfumery products and novelty fashion items [all] find much useful assistance in chromolithography.”30

Printers had mixed feelings about this transformation of the color printing industry. Godefroy Engelmann Jr., Jean Engelmann’s brother, for instance, clearly regretted the disappearance of what he described as the tasteful artistic prints and skilled craftsmanship of the early days of chromolithography:

Chromolithography has developed considerably over the past fifteen years or so, but from the standpoint of commerce rather than the standpoint of art. Color is obviously an important seduction for the public, and as soon as machines were able to produce runs for an affordable cost, merchants started using chromolithography for labels, color cards, publicity boards, and all the objects that, appealing to the eye, have the ability to attract the public’s attention.

However, the artistic aspect of our industry, far from expanding in the same way, has declined noticeably.31

Interviewed by the same Commission d’enquête on the state of French art industries, Engelmann’s competitor, the head of Lemercier et cie, agreed that their industry had by then “almost completely lost its artistic component.”32 Contrary to Engelmann, however, Lemercier’s assessment was positive. He described with great enthusiasm the ease with which mechanical presses reproduced color images, boasting that each machine yielded the work of approximately twenty handpresses. “Things are different now from when we printed on handpresses; it used to be necessary that the worker have a feeling for art, a sense of harmony to put into his drawing; now the machine is equipped to do all that work,” he commented, minimizing the knowledge and technical skill still required to operate these mechanical presses.33 In his print shop, he explained, chromolithography was now principally employed for “works destined for a great publicity.”34 The future of chromolithography, Lemercier believed, clearly lay in inexpensive mass-produced color images, not fancy reproductions of artworks patiently printed on handpresses.

Jules Chéret and the Emergence of the Artistic Poster

Posters’ accepted place in museum collections today makes it easy to forget that their recategorization as artworks was a unique and gradual affair, which cannot be solely attributed to nineteenth-century posters’ allegedly distinctive aesthetic qualities. Never before had figures of the cultural elite so enthusiastically endorsed an article of popular commercial visual culture. Some of this reevaluation was no doubt the consequence of Impressionists’ successful challenge to dominant views of what constituted a legitimate artistic subject and use of color.35 By the 1890s, Impressionists had largely won this battle, as evidenced by the high prices fetched by Monet’s, Renoir’s, and Degas’s paintings; Academic artists’ incorporation of key stylistic features of Impressionism; and the criticisms formulated by the younger generation of Symbolist and Neo-Impressionist artists, who sought to distinguish themselves from the “new normal.” Still, French elites’ enthusiastic support of poster art was not simply the result of the public gradually becoming more tolerant of bright colors in painting.

In retrospect, it is easier to see how the public response to posters and attendant practices of poster collectors arose from the particular political, economic, and social circumstances of turn-of-the-century France: the popularity of left-wing ideals among members of the artistic avant-garde; rising nationalist sentiments among large segments of the bourgeoisie, spurred not only by France’s recent military defeat by Germany but also by the unrelentingly transnational character of modern capitalism; and, finally, the pervasive classism and sexism of decorative arts reformers, who alternatively worked to reinterpret, bracket, and deny the commercial and traditionally feminine character of their field of interest. For a brief moment, and contrary to all expectation, avant-garde critics, artists, and collectors saw in the mass-produced color poster a way for capitalism, democracy, and art to coexist. Their plan, which emphasized the emancipatory potential of modern industrially produced and reproduced color, was as foolhardy as it was influential.

The figure and personality of Jules Chéret played an especially significant role in the assimilation of the poster by the art world. Born in Paris in 1836 into a working-class family—his father was a typographer—nothing predestined him for the success he later obtained as a commercial and decorative artist. Indeed, his early career was mostly marked by unglamorous commercial work and repeated financial difficulties.36 After completing a three-year apprenticeship with a lithographer, during which he learned not only to operate the press but also to make letter brochures, flyers, funeral announcements, and other miscellaneous print matter, Chéret worked for several different print shops, including Bouasse-Lebel, Simon-Jeune, and Prudont, the latter located in the town of Dole, situated in the eastern Jura region. After this brief period in the provinces, Chéret returned to Paris to work for the well-established printing house Lemercier. Around this time, he sold several drawings to editors of sheet music but was still unable to completely support himself with his artistic work. In 1858, Chéret designed his first poster for Orphée aux enfers, an operetta by the popular Second Empire composer Jacques Offenbach. “This was his first work as an artist,” writer and art critic Camille Mauclair later commented.37 Unfortunately for Chéret, the success of this first poster did not translate into more sustained work as a poster designer. Hence, after this false start, unable to find steady work as a lithographic artist in Paris, he moved to London in 1859, where he was employed by an expatriate French perfumer, Eugène Rimmel. In the end, Chéret spent seven years in London, from 1859 to 1866, exercising his eye for color by drawing floral designs and rosycheeked women for labels, trade cards, envelopes, and other perfume-related paper paraphernalia.

Chéret first became acquainted with the large color poster in London.38 With the financial support of Rimmel, Chéret returned to Paris in 1866, setting up an English-style press with which he hoped to make his mark by introducing the French to this new style of advertising. His first contracts included a black-and-green-tint poster for a féerie, La Biche au bois, and a full-color poster for the Bal Valentino, a popular Parisian nightspot. In the 1890s, critics saw these works as marking the beginning of Chéret’s career as a poster artist with a unique individual style (fig. 77). “[Valentino] appears today quite impoverished, chromatically speaking: but it was already ‘a Chéret’ by virtue of its devilish drawing and the charm of its composition,” observed Mauclair.39

FIGURE 77

Jules Chéret, Valentino: Mi-carême, grand bal paré, masqué travesti, printed by Imp. Chéret (Paris), 1866. Collection Dutailly, Les Silos, Maison du livre et de l’affiche, Chaumont, France.

It was not long before Chéret, first as owner of his very own print shop on rue Bunuel and then under the masthead of the much larger Imprimerie Chaix, changed the look and feel of outdoor advertising and, by extension, the look and feel of Paris. Indeed, contemporary observers frequently identified the artist’s posters as one of the main contributors to the city’s shifting and mobile polychromatism. “Against the regnant sad, gray background,” wrote Joris-Karl Huysmans, “Mr. Chéret’s posters contrast sharply and throw off balance by the sudden intrusion of their joy into the still monotony of the prison-like décor . . . ; this dissonance jeopardizes Mr. Alphand’s entire project.”40 Contrary to Hippolyte Taine, who decried the horrible glare of English women’s attire in the 1860s, or Charles Blanc, who did the same in response to French women’s outfits in the 1870s, Huysmans celebrated the loud colors of Chéret’s posters. Indeed, according to the writer, the optical scandal Chéret’s work created was a welcome disruption to the gray monotony of Haussmannian Paris.

The arguments that raised Chéret’s posters to the rank of high art came from various sources. And while this collection of ideas did not result in an absolutely coherent message, some dominant themes and recurrent tropes clearly emerge, especially in the articles and essays of the select group who wrote often and enthusiastically about Chéret’s work in the 1880s and 1890s. Huysmans was the first art critic to write about Chéret. He did so in his reviews of the 1879 and 1880 Salon exhibitions, where he contrasted the sterile Academic artworks of the official shows with the cheerfulness and originality of Chéret’s posters displayed outside on the streets of Paris. “A thousand times more talent went into the slimmest of these posters than most of the paintings I had the unfortunate privilege of reviewing,” he concluded in 1880.41 Obviously, Chéret’s posters contrasted sharply with the dark, highly finished oil paintings exhibited at the Salon. But wherein exactly lay the originality of posters, or, moreover, their beauty? Since the purpose of Huysmans’s comparison was mostly to criticize official art exhibited at the Salon—“all the little-bitty cat-lick paintings in the style of Cabanel and Gérôme” (toutes les léchotteries à la Cabanel et à la Gérôme), as he put it—rather than to analyze Chéret’s work, this crucial question remained largely unanswered.42

As critical interest in posters mounted, it was not long before someone took a more careful look at Chéret’s designs. This role was filled not by an established art critic but by an employee of the French Institute and avid poster collector, Ernest Maindron. His two articles, published in La Gazette des beaux-arts in 1884, likely constitute the first historical and critical analyses of the French poster ever published. Like Huysmans, Maindron confidently vaunted the artistic merits of Chéret’s posters. “All those interested in real art recognize in Mr. Chéret a quality that makes him worthy of a privileged rank among lithographers,” he wrote.43 More precisely, according to Maindron, what made Chéret’s posters especially worthy of attention was the simplicity of their composition, their eye-catching yet harmonious coloration, and their distinctly French character. Chéret, Maindron explained, avoided crowding his designs with too many details. His drawings were elegant, not overwrought: “Nobody before him had so clearly demonstrated that the illustrated poster needed to impose itself not only by the general aspect of its coloring but also by the elegance of its lines and the simplicity of its composition. It is with these qualities that [the poster] raises itself to the status of art and succeeds in grabbing attention of admirers.”44

Unlike others, Chéret used color intelligently and with purpose, Maindron insisted. He juxtaposed large, contrasting masses of colors, combined in such a way as to create a powerful yet coherent impression: “It is impossible to see one of his designs without immediately grasping the nature of the work he puts forward. If the eye is satisfied, the spirit is no less so. His posters stand out on the walls and command the attention. That is their whole purpose.”45 In other words, Chéret’s posters were original creations perfectly adapted to their function. This was because, instead of adapting preexisting artworks for the purpose of advertising, as so many commercial artists were in the habit of doing, Chéret invented a new visual language, which, according to Maindron and his predecessor Huysmans, simultaneously revealed the inadequacy of mainstream advertising and Academic art.

Along with Maindron’s groundbreaking articles, Henri Béraldi’s portrait of Chéret in Les Graveurs du XIXe siècle, a multivolume work published between 1885 and 1892, did much to solidify the Parisian poster designer’s status as an artist. “Many of his posters are paintings—paintings made using simple methods suited to industrial and low-cost production, but paintings [nonetheless],” wrote Béraldi.46 Like Maindron, Béraldi praised the simplicity of Chéret’s design, noting how this simplicity was both appropriate, considering the poster’s commercial function, and artistically interesting in its own right. Chéret had learned how to “achieve the maximum effect with a very small number of colors and use the letters, titles, and captions as ornamental motifs.”47 Simple yet arresting, the colors of Chéret’s posters were beautiful by virtue of fulfilling their function and were easy to produce using the tools at hand.

Félicien Champsaur, Frantz Jourdain, and Roger Marx, the latter of whom wrote extensively on art matters in the 1880s and 1890s, all the while holding a variety of arts-related government positions, publicized Chéret’s work in both mainstream newspapers and specialized publications, such as La Plume, L’Estampe et l’affiche, and Les Maîtres de l’affiche, adding to the number of chérolâtres in the process. While the purpose and emphasis of these articles varied, they collectively created the clear impression that what was most important about Chéret’s posters was their formal aesthetic qualities. “His posters, attractive visions of colors combined together with a prodigious cleverness, brilliant like poppies growing out of holes in the walls, are blushing and eye-catching bouquets,” noted Champsaur in Le Figaro.48 Described as bouquets, fireworks, and splashes of paint, Chéret’s posters, critics argued, were spectacles of pure color, practically devoid of meaningful subject matter and, by extension, commercial purpose. Advertising, some insisted, was a mere “pretext” for artistic creation.49

Several writers described the sight of Chéret’s posters from a distance, further emphasizing the play of nonmimetic colors, as in the following passage by the artist-journalist Georges Dubosc: “From a distance, all the riches of these singsong colors blend together and settle, leaving only [for example] the bright yellows of skirts to dominate and find their natural complementarity in deep and mellow blues. In which case, you are no longer in the presence of a simple printed poster, an insipid product of industry: you feel like you might simply be surprised by the originality of the drawing, but you are looking at a proof that still conveys something of the flame and light of a quick and lively sketch drawn by a master.”50 Indeed, borrowing from the language of Impressionism, critics were particularly fond of discussing Chéret’s posters in terms of sunlight. “In these last beautiful days of fall, is it not a true and delightful pleasure to see appear on one of our sullen walls a triumphant poster where Chéret evokes, with a luminous symphony of yellow and blue, the allure of the next departure for the land of sunshine?” asked Dubosc.51 In such estimations, critics skillfully suppressed the chemical origins of the inks and, as previously noted, the lithographic process in general.

Writing in 1898, writer and art critic André Mellerio likewise pointed to formal pictorial qualities to demonstrate how, no longer an art of imitation, chromolithography was now the source of original works of art that could stand up to serious review and criticism. Chéret’s posters, he insisted, had set the tone for the original art prints that were now being produced by a growing number of avant-garde artists, including Paul Signac, Maximilien Luce, Maurice Denis, and Alexandre Lunois, among others: “The modern print was no longer a facsimile reproduction of just any original work in color, but a personal conception, something realized for its own sake. An artistic inspiration joined in advance with a technique expressed itself indirectly in the chosen process of execution.”52 In his use of large colored tint areas, full tones, hair-line pen strokes, and the splattering technique known as crachis, Chéret had been the first to frankly state the physical properties of his materials and methods of production. This frankness ensured not only the work’s originality, Mellerio hinted, but also its inherent beauty and moral character. It was Chéret’s commitment to these formally innovative, medium-specific techniques and to the creation of images “realized for [their] own sake” that made him a bona fide artist, indeed, of the very same order as the creators of the original art prints that were Mellerio’s focus.

That Chéret was not only an illustrator but also trained as a printer was central to how critics understood him and his work. In their view, Chéret’s intimate mastery of lithographic technology dictated the simple elegance of his designs. His posters, they claimed, exemplified the perfect harmony between form and function, between formal compositional elements and the technological means by which they were produced.53 And yet, the diversity of color lithographic products and styles in Chéret’s oeuvre alone indicates that little about the artist’s engagement with chromolithographic materials and machinery was necessary or self-evident. In other words, when critics paid homage to modern production methods, they were largely paying homage to a fantasy of their own invention.54

According to the same group of people, Chéret had successfully transformed the colorfully illustrated poster, an Anglo-American invention, into something distinctly and recognizably French, generally citing the refinement and delicateness of his designs and harmonious use of color as evidence: “Chéret is a virtuoso of color; it has become even banal to say this. The boldness of the coloring, the neatness of the drawing, the lightness of the touch, the suppleness and vivaciousness of the movement, these are his main qualities. Are they not typically French, do they not explain the revolution brought about by this ex-apprentice lithographer to the art of color poster making, which before him was so heavy, so clumsy, and as different from art as popular images are from prints.”55 In other words, the primary difference between Chéret’s posters and those produced by American or English artists resided, first and foremost, in the former’s technique and the posters’ formal qualities. Compared to Chéret, the impression produced by English and American poster designers was brutal and coarse, critics complained. The Anglo-American poster hollered, whereas Chéret’s charmed. Chéret’s posters were eye-catching but always remained tasteful, refined, and gay. Indeed, as one journalist put it, “Parisian posters . . . succeed in idealizing the most vulgar things, lend a touch of pleasant and charming fantasy, and evoke in a picturesque manner all aspects of modern life.”56

Nationalism played a big part in critics’ defense of the poster’s special status. They frequently drew parallels, for instance, between Chéret’s brazenly commercial fantasies and the art of François Boucher, Jean-Antoine Watteau, and Jean-Honoré Fragonard.57 “The thing is, Chéret is all Parisian; [he is] French, of course, with ties to Watteau!” wrote Gustave Kahn.58 As with Napoléon III’s taste for fireworks displays reminiscent of the ancien régime and the return to brighter colors in women’s fashion starting in the late 1850s, following the example of Empress Eugénie, the Rococo served as an important reference point for cultural observers attempting to make sense of the bright exuberance of modern mass-produced and -reproduced color.

Buttressing this same point about the distinctly French character of Chéret’s designs, critics specifically drew attention to the artist’s working-class background. “He comes straight from the people. The son of a worker, he was himself a worker,” noted a journalist writing for L’Éclair.59 It was precisely these origins, another insisted, that explained why the commercial artist and printer was never seduced by the supersizes and crudeness of American posters: “I notice that, having mastered the manipulation of these large stones, Mr. Chéret never fell into the trap of excess, of gigantism, like the Americans. (Do you remember the Buffalo Bill and d’Amour posters?) This is because the artist was a good Parisian worker, whose racial traits are the sense of measure and good taste.”60 In short, although posters emerged from and circulated within transnational commercial and cultural networks, critics almost always spoke of them as being limited to a nationally defined market and aesthetic imaginary.61 This insistence on the Frenchness of Chéret’s posters not only reversed the traditional notion that the French were too civilized to take pleasure in bright colors, but also marked posters as distinct from the mass of colorful advertisements produced in the final decades of the nineteenth century.

It should be clear by this point that the discourse on posters was formulated in direct opposition to run-of-the-mill commercial chromolithography as defined by late nineteenth-century tastemakers, many of whom held partial, generally outdated views on the subject. Many voices from the poster world continued to insist on the preponderance of facsimiles of artworks, despite the fact that, as we have seen, these constituted only a small and ever-dwindling portion of the color images that printers produced. Memorable posters designed by well-known artists were good advertisements for those who produced them, and it is not surprising that such printers often made special reference to them in promotional materials (fig. 78). As evidenced by their actual list of products, however, it is clear that printers and the artists who worked for them espoused a much broader understanding of what constituted an appropriate use of chromolithography: the “artistic poster” was only one option among many.

FIGURE 78

Imprimerie Camis, printed by Imp. Camis (Paris), 1896. Bibliothèque des arts graphiques collection, Bibliothèque Forney, Paris.

Indeed, it is telling that, despite their insistence on production methods, poster aficionados had remarkably little to say about printing.62 Details about who printed the posters, using what kind of press and inks, and other technical information are noticeably absent from most contemporaneous writings about posters, suggesting that, much like twentieth-century references to the “machine aesthetic,” these nineteenth-century mentions of function and production methods conceal as much as they reveal. In the end, the most important differences between posters and other colorful paper paraphernalia, namely trade cards, were not technological or even stylistic but rather social and political. Established as a respectable hobby for artistically minded gentlemen with antiestablishment aesthetic and political views, poster collecting became the model for an alternative interpretation of color in everyday consumer culture, at once more masculine and more French than what had come before.

Chromos

As noted before, trade cards, also known as chromos, constituted a significant portion of chromolithographic production at the time, and many French printers who made posters also produced these small, richly colored images. Exemplary of the disposable color paper prints made possible by the introduction of mechanical presses, these cards, distributed free of charge by retailers and manufacturers, were at once more visually enticing than handbills and more strictly commercial than calling cards. “Today, we print little images that are distributed free of charge to children by large magasins de nouveautés. There’s a series of fifty to sixty of these images that bear, on the flip side, a text [un programme] that is an advertisement. You see how chromolithography has been completely assimilated into the industrial arts,” noted Lemercier.63 Similarly, Bouchot viewed trade cards as a prime example of what printers were now capable of producing thanks to the advent of technologically sophisticated mechanical presses: “Automatic registering is trustworthier and more precise and the cost price much lower. That is why we see, at the present moment, so many chromolithographic images sold at a very low price, which lack neither in art nor spiff. The magasins de nouveautés flood us with figurines thus produced by the thousands, of which the rare survivors, saved from the hands of children, will someday be included in collections and constitute for our descendants what are for us today the colored aquatints of Debucourt, Sergent-Marceau, or Levachez.”64 Posters were not, in other words, the only type of chromolithographic prints worth producing. Trade cards, too, Lemercier and Bouchot insisted, were eminently well suited to lithographers’ means of production.

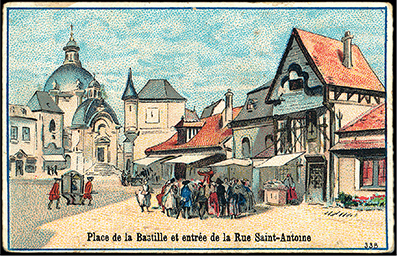

As the trade card collections held at the Musée des civilisations de l’Europe et de la Méditerranée attest, these small paper advertisements featured a dizzying array of subjects from worldfamous architectural monuments to amusing and bizarre scenes of make-believe (figs. 79 and 80). In most cases, the images bear little or no relation to the product or business advertised. In fact, unwilling or financially unable to invest in custom-designed trade cards, many advertisers relied on stock designs, which they personalized by overprinting or stamping with their business’s name and apposite advertising copy. Illustrations frequently included blank spaces—a conspicuously empty scroll, crest, or larger than usual expanse of sky—specifically reserved for this purpose (figs. 81 and 82). As these characteristics suggest, trade cards were a more accessible and versatile form of advertising than posters and, as such, provide scholars with a much broader view of late nineteenth-century consumer culture. From P. Marie, a grocer on rue Saint-Pierre in Caen, to the well-known La Samaritaine department store in Paris, few businesses did not take advantage of this popular and inexpensive advertising medium.

FIGURE 79

Trade card depicting the place de la Bastille and entrance to the rue Saint-Antoine, printed by L’Héritier & Dupré, 1875–1900. 6.5 cm × 10.2 cm. Musée des civilisations de l’Europe et de la Méditerranée, Marseille.

FIGURE 80

Trade card featuring asphyxiated children lying on a slice of cheese, printed by Appel, 1875–1900. 6.8 cm × 10.8 cm. Musée des civilisations de l’Europe et de la Méditerranée, Marseille.

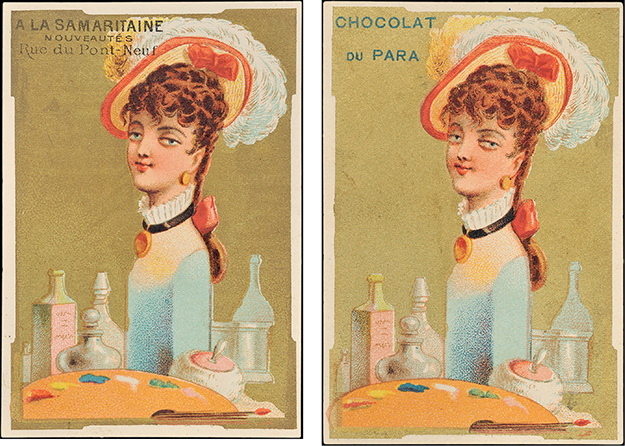

Figures 81, 82

Stock trade cards with woman’s head, bottles, and paint palette, among other items, overprinted with the name of the Parisian department store La Samaritaine (fig. 81) and the Chocolat du Para firm (fig. 82). Printed by Appel, 1875–1900. Each 7.2 cm × 10.6 cm. Musée des civilisations de l’Europe et de la Méditerranée, Marseille.

Merchants most likely began using trade cards to publicize their goods and services sometime in the seventeenth century.65 Only in the nineteenth century, however, did the small, colorful images printed on card stock become commonplace. Most sources credit Aristide Boucicaut, the astute businessman behind Paris’s first department store, Le Bon Marché, with starting the chromo trend.66 Whatever the case, by the late nineteenth century the famed Parisian department store was among the country’s principal producers of trade cards. Between 1895 and 1914 alone, Le Bon Marché distributed more than fifty million chromos, representing more than three hundred different models.67

Several key differences set trade cards apart from their better-known chromolithographic sibling, the poster. Compared to posters, which ranged in size from approximately 122 by 82 centimeters (a format known as double colombier) to 164 by 122 centimeters (quadruple colombier), trade cards are a much smaller and far more intimate form of advertisement. Approximately 7 by 11 centimeters, trade cards fit easily into shoppers’ hands. The chromos’ detailed, often sentimental, imagery was designed for close examination, rather than the furtive glances of passersby. The cards were, moreover, often issued in a series, and their subject matter is what connected and differentiated them from other series. Common themes included pretty flowers, children playing grown-up or engaged in some other humorous activity, and scenes of bourgeois motherhood. The cards’ diminutive size and sentimental imagery, to say nothing of collectors’ habit of assembling them into scrapbooks, sometimes next to calling and greeting cards, inscribed the colorful images within the domain of nineteenth-century bourgeois femininity and its attendant aesthetic and affective conventions.68 As Naomi Schor argues, in Western philosophy and aesthetics, synthesis and clarity have typically been characterized as male, whereas the proliferation of details, excessive variety, and ornamentation have typically been labeled feminine.69 Art critics spoke of the feminine wiles of the scantily clad, nymph-like women that appeared in Chéret’s posters. In theory, however, the form of the poster, which critics promoted as rigorously functional and synthetic, was utterly masculine in nature. That posters were, in actuality, mostly collected by men, while trade card collecting was mostly the prerogative of women and children, did little to undermine these gender stereotypes.

Indeed, like posters, trade cards were an excessively popular collector’s item in the late nineteenth century. Contrary to the well-educated, bourgeois male poster collector, however, the trade card collector was more likely to be a woman or a child, and, save for a few exceptions, their identities have generally not been recorded. In fact, in organizing its trade card collection by printer, rather than by collector, the Musée des civilizations de l’Europe et de la Méditerranée permanently erased all traces of the original owners and the significance she, most likely, derived from assembling and ordering the collection. Even Le Vieux Papier, the French ephemera collectors’ association, founded in 1900, initially kept its distance from trade cards and their collectors. Passing references to trade cards sometimes appeared in its journal, but for the group’s first fifty or so years of existence, there was no article specifically dedicated to the subject.70 Even among ephemera collectors, in other words, chromos were tainted with an undesirable reputation.71

Finally, in sharp contrast with poster aficionados’ insistence on the inherent Frenchness of Chéret’s designs, trade cards partook in what can only be described as a transnational commercial aesthetic. Until the erection of protectionist tariffs by most European governments in the 1890s, printed paper products of all kinds circulated widely between countries. As Lemercier explained to the Commission d’enquête that was investigating the state of French art industries, “We generally print chromos in runs of three thousand and we send them, so to say, everywhere.”72 The abundance of stock trade cards produced in France, stamped with the names of U.S. businesses and found today in U.S. ephemera collections, confirms the printer’s statement.73 While perhaps first introduced in the mid-nineteenth century by the owner of a Parisian department store, no one by the end of the century could specifically lay claim to the trade card’s content or form.

Posters’ often-lurid imagery, simplified forms, and loud colors were the exact opposite of what more mainstream connoisseurs considered art. And, in a way, that was precisely the point. As Karen Lynn Carter argues, affichomanie (literally, “postermania”) originally emerged in the late 1880s and early 1890s as an elite antibourgeois activity.74 Akin to the experienced flea-market-goer capable of spotting treasure in a pile of junk, collectors selected posters from all the colorful ephemera printed at the time as uniquely valuable. Where others saw rubbish, destined to quickly disappear, these collectors saw the future of modern art.

Drawing upon their vast reservoir of cultural capital, Huysmans, Maindron, Marx, and their followers successfully convinced large numbers of educated, bourgeois men that it was possible to consume posters differently from how their creators had intended, that is, to consume posters not as mere advertisement but as art. It is hardly surprising, therefore, that poster collectors generally presented themselves as attracted first and foremost by an image’s purely aesthetic qualities. Shapely naked thighs, exposed bosoms, seductive glances, not to mention the actual product being advertised, were never the focus of collectors’ attention, or so critics suggested. “[The posters’] audacities are covered by the immunities of Art,” Gustave Bourcard’s exhibition catalogue noted.75 Indeed, while critics sometimes called attention to posters’ value as historical sources—Chéret’s designs provided a chronicle of “our habits, our mores, our costumes, our food, our readings, our illnesses, our pleasures especially,” Béraldi noted—critics generally focused more on their formal aesthetic characteristics: line, color, texture, space, and so on.76 The public rhetoric surrounding affichomanie thus explicitly distanced posters from the detailed colorful illustrations featured on trade cards, reinforcing the notion that the two artifacts of nineteenth-century print culture were polar opposites in practically every respect.

Confirming this dichotomy, recent studies of trade cards have mostly focused on iconography, treating their imagery as windows onto contemporary beliefs about race, gender, class, or some other exogenous historical category or event.77 Their conclusions underline the special function of widely shared, deeply rooted visual stereotypes in advertising.78 By ignoring formal considerations, however, such studies also have the cumulative effect of reinforcing the idea that there is nothing to say about the styles and techniques of trade card imagery. Indeed, it is telling that, when faced with the challenge of describing the vaguely naturalistic, vaguely fantastical style of mainstream commercial visual culture, scholars have often found it necessary to borrow from other languages or have invented entirely new expressions, such as the German word kitsch (Clement Greenberg’s favorite); Northrop Frye’s “stupid realism”; and Michael Schudson’s “capitalist realism.”79

Coined in the twentieth century long after trade cards stopped being popular, these labels are nevertheless useful for understanding trade card imagery, namely by bringing attention to the varied ways that mainstream commercial art generalizes, typifies, and enhances, often in fantastical ways, the objects, people, and events of ordinary life. Indeed, while obeying the standard conventions of naturalistic depiction, including rules of perspective, proportion, and coloration, the images that belong to this informal category always fall short of actually picturing reality. The men, women, and children featured on trade cards are more often types than real individuals. A fair number of them read as alternatively timeless, placeless, or both. In short, the reality featured in trade cards was always a selective and generalized one, populated with numerous abstractions. Indeed, as Schudson puts it, “abstraction is essential to the aesthetic and intention of contemporary national consumer-goods advertising. It does not represent reality nor does it build a fully fictive world. It exists, instead, on its own plane of reality, a place I will call capitalist realism.”80

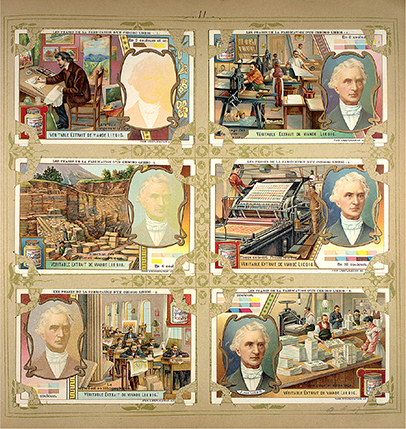

Not surprisingly, color was one aspect of nineteenth-century reality that trade card imagery was particularly successful at abstracting and presenting back to viewers in a memorable and eye-catching manner. Many trade cards, for example, illustrated the chromolithographic printing process. In addition to depicting the different stages involved in the production of trade cards, from the commercial artist’s preliminary drawing to the card’s final distribution, the series in figure 83 featured six portraits of the German chemist Justus von Liebig, each at a different stage of completion. Known as progressives or progressive proofs, these images were a way for printers to evaluate the quality of their work. In the Liebig series, however, the effect is to glamorize the artistic and technological process by which trade cards were produced, featuring color at the expense of straightforward transparent representation. Much like Chéret’s posters, this and similar trade card series depicting the chromolithographic printing process loudly touted their industrial origins and celebrated color for its own sake. In fact, by almost every measure, these small advertisements, adorned with printing presses and color bars, did so even more explicitly than their larger and more highly valued chromolithographic counterparts.

FIGURE 83

Series of six trade cards published by the Liebig company, depicting the production of trade cards, ca. 1906. Courtesy of the Rare Books Division, McGill University, Montreal, Canada.

Trade cards also brought attention to color by incorporating into their designs paint palettes, rainbows, flowers, and other familiar objects that simultaneously exemplified and symbolized the idea of color. In the chromo in figure 84, for instance, a young girl brushes red paint on her cheek in a casual manner recalling the application of makeup. The inscription reads “Un peu de couleur ne nuit pas”—a little color doesn’t hurt—echoing the utterances of cosmetics enthusiasts. Interpreted in a slightly broader sense, however, the caption can also be read as a plea for more color in fashion and the home, whether in the form of trade cards, posters, or other colorful consumer goods, such as the shirts and lingerie sold by the advertiser, Langlois et Legallier. As the girl’s actions and artistic accessories suggest, more than simply “not hurt[ing],” color served a constitutive role in nineteenth-century picture making and visual experience more generally.

FIGURE 84

“A Little Color Never Hurts” (Un peu de couleur ne nuit pas), trade card, printed by Bognard, 1875–1900. 8.2 cm × 11.2 cm. Musée des civilisations de l’Europe et de la Méditerranée, Marseille.

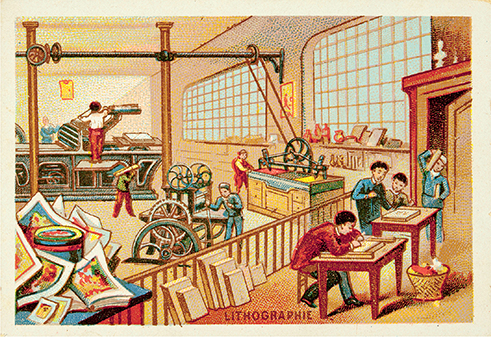

In short, contrary to the long-standing notion that popular commercial imagery was unwaveringly realistic, it is clear that nineteenth-century trade cards, much like the posters that earned critics’ praise, offered viewers an abstracted representation of the world, which often drew attention to color’s nonmimetic, self-referential qualities. Far from trying to pass for another, more prestigious medium or offer a transparent representation of the world, these small advertising images highlighted their mass-produced colors, often for their own sake. On occasion, this happened accidentally, as in figure 85, where imprecise color registration causes hues to drift outside the drawing’s outline. Out of place, the red, blue, or yellow surfaces draw attention to themselves qua color. More often, however, viewers’ attention was purposefully directed to color by the deceptively simple—or, as Frye and Schudson would have it, “stupid” and “capitalist”—design itself. As such, the single most important difference between advertising cards and posters resided not in their inherent aesthetic qualities, which similarly emphasized color’s mass reproduction and uncanny ability to simultaneously represent reality and draw attention to itself, but in the social identities of their respective collectors and advocates.

FIGURE 85

Trade card showing the interior of a printshop, printed by Dessain, 1875–1900. 7 cm × 10.1 cm.

The Politics of Poster Collecting in the Era of Physiological Optics

Compared to the identities of trade card collectors, those of poster collectors are much easier to trace. Distancing himself from the collectors of arcane prints of yesteryear as well as from the trade card collecting habits of women and children, Maindron opened his first article on posters, published in 1884, with the following assertion: “Collectors are very respectable men.”81 Poster collectors’ respectability, however, was very different from that of more mainstream art collectors. By heralding the loudly colored, mass-produced poster as one of the most important art forms of the times, Huysmans, Maindron, Marx, and their followers intentionally distanced themselves from the well-trod paths of the Parisian art world. After all, posters were not originally designed with collection in mind. Their first collectors had to devise unusual, often illegal tactics to obtain the large outdoor prints, gaining a reputation for eccentricity and troublemaking in the process.82

According to critics, posters had the unique merit of being a more democratic, and more original, art form than the paintings, sculptures, and other works of fine art exhibited at the Salon. Indeed, many supporters of the artistic poster, notably Marx, who played a leading role in the art social movement in France, were deeply invested in the idea that art should be part of quotidian experience.83 Some advocates, namely Fénéon and Kahn, interpreted the poster in explicitly socialist-anarchist terms. In their view, more than simply improving public taste, Chéret’s posters functioned as the unlikely agents of a broad politico-aesthetic revolution. In striking contrast to the actual social status of poster collectors, Fénéon, for example, in the anarchist journal Le Père peinard, invoked a working-class affichomane, who stole large colorful prints from the streets in order to liven up his humble living quarters. “A Lautrec or a Chéret in the home, that really brightens things up, by Jove! It throws into the room a deadly blast of color and giggles. Of course, posters have a hell of a size. For very little money, therefore, you can get yourself an artwork that has more style than any of those horrible paintings done in licorice juice that enthrall rich assholes [trous du cul de la haute],” he exclaimed, employing the distinctive argot of the French working class.84

For Kahn, posters announced the polychromatic socialist society of the not-too-distant future. In his 1901 L’Esthétique de la rue, a book-length study of the past, present, and future of public art, the poet outlined an improbable connection between late nineteenth-century posters’ brilliant colors, the splendors of the ancien régime, and socialism. Meditating on what the future would offer the worker hungry for both justice and beauty, he mused, “The mobile decoration of the street can be supplied by the free spectacles of advertisement, which are increasingly common. A perfected social state can get rid of advertising but keep the amusing idea of polychromatic shadows to amuse passersby, those who aren’t going to the Social Club or Popular Theater that evening.”85 Like others before him, he emphasized the joyousness of Chéret’s designs, insisting in a later text, “Celebration—Chéret said it better than anyone with his posters.”86 Chéret himself readily admitted that he had no interest in depicting the uglier aspects of everyday life. In the context of the poet’s other writings on color from the same time period, however, Kahn’s characterization of the commercial artist as the quintessential painter of joy took on a markedly different, more scientific connotation.

Moving away from Michel-Eugène Chevreul’s law of the simultaneous contrast of color, Kahn and members of his entourage, including Fénéon and Neo-Impressionist artists Paul Signac and Georges Seurat, turned their attention in the late 1880s to the more recent psychophysiological analyses of color by the eccentric polymath Charles Henry.87 Contrary to Chevreul, who pointedly avoided investigating the psychophysiological cause of contrast effects, focusing instead on the applications of his theory, the younger scientist was uniquely preoccupied with these types of questions. More specifically, using an instrument he called the dynanomètre physiologique, which he devised for measuring muscular reactions, Henry focused on precisely qualifying and quantifying responses to different visual stimuli, including, most notably, line and color. This quantification allowed Henry to develop other tools, such as the rapporteur esthétique (aesthetic protractor) and cercle chromatique (color wheel), for evaluating both the conditions of normal human perception and the beauty of artistic designs. “I have succeeded in specifying what we must consider as the normal and in establishing. . . a method that offers science’s fundamental hypotheses all the certainty of which they are capable.”88 More specifically, a “normal subject,” Henry concluded, would experience an energizing pleasure when perceiving ascending lines and warm colors and a weakening unpleasant sensation when perceiving cool colors and descending lines.

Compared to Chevreul, whose credentials were indisputable, Henry occupied a much more tenuous position vis-à-vis the French scientific establishment. Trained in mathematics, he worked for most of his professional career as a librarian at the Sorbonne, before receiving a position as director of the Laboratoire de physiologie des sensations at the same university.89 He enlisted the assistance of Charles Féré, a physician employed at the famed French asylum La Salpêtrière, to conduct experiments using his equipment but does not seem to have had any medical training himself. More to the point, however, whereas, for Chevreul, the quantification and standardization of color was primarily a practical industrial matter, for Henry the subjective experience of color and the perceiving subject were the object of quantitative control. In other words, instead of focusing on the colorful industrial product, stubbornly resistant to standardization, Henry directed his attention inward to the internal chemistry of physiological reactions. For contrary to the infinite variety of styles and colors of the marketplace, general physiology, as the scientist himself termed the focus of his investigations, more easily lent itself to the identification of averages and standards, both psychophysiological and aesthetic.

In Henry’s explanation of the generative function of color (and line) and attendant interpretations by Neo-Impressionist artists, art historians have rightly seen one of the important sources of abstract art.90 Equally significant, however, especially in the context of the late nineteenth-century avant-garde’s embrace of posters and industrially produced color, is the scientist’s conspicuous failure to identify the age, gender, race, or class of the normative perceiving subject, whose reactions to color he sought to codify. Indeed, contrary to the numerous scientific publications that promoted the idea that children, women, workers, and other “uncivilized” people were particularly sensitive to the appeal of color, Henry revealed nothing about the identity of the universal “normal” subject. Men, too, Henry thereby suggested, were influenced by the dynamogenic effect of warm colors and the inhibitory effect of cool ones. Around the same time, German psychologist Jonas Cohn published a study, soon translated into French, demonstrating that bourgeois men, far from shying away from bright, saturated colors, actually preferred them.91 Along with Henry’s studies, this new understanding of human color perception reversed decades of popular and scientific lore. Psychophysics provided critics, then, with a new scientific language with which to think about bourgeois men’s engagement with posters and modern mass-produced color more generally. Indeed, it is hardly surprising that Kahn, an ardent supporter of the artistic poster, also greatly contributed to the popularization of Henry’s color theory in Symbolist and Neo-Impressionist circles.92

The form of synesthesia known as color hearing, whereby the sight of a color automatically triggers an auditory experience and vice versa, became an increasingly dominant point of reference for members of the artistic and literary avant-garde seeking to describe the experience of color as separate from line, form, and figurative representation altogether. Drawing upon the same cultural trend that inspired James McNeill Whistler to title his paintings nocturne and symphony, Jean Lorrain, for example, described Chéret’s posters as “Japanese brass-bands of color” and “painted waltzes.”93 Whether used in reference to Whistler’s nocturnes or Chéret’s much less prestigious production, the overall effect of these analogies was largely the same, that is, to heighten the abstract quality of color. Indeed, the idea that a parallel existed between color and what was imagined as the inherently nonobjective character of music had become something of a truism among fin-de-siècle French artists and intellectuals. Earlier in the century, Chevreul had actively resisted this idea, insisting instead on the purely optical and self-referential quality of color; in his view, the association with sound could only undermine the notion that the study of color was sui generis—a modern, autonomous, and purely scientific field of inquiry, divorced from older scientific and philosophical inquiries into the subject.

The extent to which critics’ descriptions of posters in auditory terms were influenced by Henry’s ideas or, especially, Féré’s efforts to identify the psychophysiological origins and significance of synesthesia is unclear. Both men explicitly viewed the perceptual phenomenon as pathological rather than as a blessed sign of artistic genius, as Symbolists generally believed.94 Indeed, as Féré readily recognized, interest in synesthesia vastly exceeded the small world of psychophysics. Popular culture, he noted, “seems to have recognized the phenomenon before it attracted scientific attention and gave it a role in metaphorical language.”95 Compared to bona fide psychophysiological synesthesia—confirmed by “empirical observation,” Féré specified—metaphorical or cultural synesthesia, especially as articulated by fin-de-siècle Symbolist artists and critics, added an affective or spiritual quality to color; the relationship between color and music was largely tautological.

In the context of the reception of Chéret’s posters, these parallels recalled themes found elsewhere in art criticism—Mauclair, for instance, was particularly fond of comparing Monet’s painting with Debussy’s music—thus heightening the prestige of the commercial artist’s work.96 Perhaps most importantly, however, the supposed relationship between color and music allowed the bourgeois elite who collected posters to imagine the commercial public sphere as culturally, if not psychophysiologically, far more unified than it was in reality. It is not hard to see how the idea of there being a unity between sight and hearing enabled fin-de-siècle artists and intellectuals to imagine a world in which individual and collective identities, too, could be harmoniously unified.97

Revolution Deferred: Fin-de-Siècle Collection Practices and the “French” Poster