Chapter Six

The next morning Emily awoke to the squawk of sparrows when Aunt Liz opened her bedroom window. The air smelled fresh and clean in the aftermath of yesterday’s rain.

“Wake up, sleepyhead.” Aunt Liz laughed and jostled Emily’s arm as she sat down on the edge of the bed. “I have to leave, Em. Gotta get back to Winnipeg.”

“Bye, Aunt Liz. I’ll see you in a couple of weeks.” Emily sat up sleepily and gave her aunt a hug. “Have a safe trip back.”

“Thanks, kiddo. Take care of yourself.” Her aunt got up and went across the room towards the door, then paused at the head of the stairs. “By the way, Emily. I had a talk with your mother last night about taking it easier, not working so hard. She said she’d try, but you know how she is.”

“Yeah, I know. She’s a workaholic.” Emily fiddled with her hair, and lay back on the pillow. “I just wish she’d take time to go out for a walk or a bike ride or something. She never relaxes.”

“She’s under a lot of pressure, you know. Trying to meet demands and pay the bills. It’s not easy running your own business. But it’s important that she take time for herself too.” Liz walked over to the mirror and straightened her blazer. Emily liked the way her aunt dressed – a professional, yet casual look, not too old-ladyish. Her grey-blonde hair was neatly in place, yet it looked natural. Aunt Liz smoothed her skirt and headed for the stairs again. “I’ll work on her when I get back. In the meantime, just keep inviting her for walks and maybe she’ll take you up on it sometime.”

“Okay, Aunt Liz. Thanks.”

“Bye, sweetie.”

“Bye.”

Aunt Liz’s head disappeared down the staircase and Emily slid out of bed. As she dressed she could see her aunt get into her car and drive off, showering gravel down the driveway as the car sprinted away. Someday I’m going to have a car just like that, thought Emily. Then she dashed down the stairs, meeting her mother in the second floor hallway.

“Morning, Mom. Could I go see if I can find Emma…?” She stopped short. She’d almost blurted out “and ask her about her family?” Good thing she’d caught herself before her mother asked more awkward questions.

“Morning, Em. Well, I guess so.” Kate’s face creased with a frown, as she considered Emily’s request. “I have to spend some time with Gerald Ferguson going over the business arrangements for the farm this morning. But this afternoon you’ll have to come with me to town – if I can get Gerald to give us a ride.” Kate looked at her daughter and suddenly gave her a hug. “You go on, but grab something to eat first, okay?”

“Okay. Thanks, Mom.” Emily was relieved. She and her mom had a truce again. She raced downstairs.

In the kitchen Emily scrounged around for a plastic bag, then grabbed a sandwich left over from lunch the day before and tucked it inside. Outside, Mr. Ferguson, who was just driving into the yard in his half-ton, waved and grinned at Emily. He was knocking on the door as she strolled across the prairie, chewing her egg-salad sandwich.

The ground was damp. She could feel the moisture leaking into her sneakers. Wet grass and weeds smacked at her pant legs, until the bottoms were soaked to her calves, but she didn’t care. The foliage everywhere was brilliant green, and the sun glinted off the bright blue of the slough as she passed. Two swallows swung and dipped over the power lines, headed for her grandparents’ barn. The leaves on the trees had seemingly popped out fully from buds overnight, and the air smelled fresh and clean.

Emily breathed deeply and ran. When she reached the boulder she climbed part way up and groped in the crevice for the special stone. She’d decided to take it with her in case Emma hadn’t come. Just as she touched its smooth coolness, she trembled and felt herself slipping…The scenery shifted. She slid the stone into the pocket of her jeans, then scaled the top of the rock – where Emma waited for her.

“Hi, Emma. Isn’t it a glorious day?”

“Indeed, it is a grand July day, Emily.” Emma rose to greet her. “Come on, lass. I want to show you our new home. We moved in a couple of weeks ago.”

The two girls climbed down from the rock and followed the trail across the meadow.

“It poured buckets yesterday,” Emily exclaimed as they waded through vegetation dripping with moisture. “Looks like it did here, too.”

“Yes, it rained here, but we were cosy and dry in our new house.” Emma stopped and bent over. Her fingers parted the foliage. “Look Emily. Mushrooms.”

“Don’t touch that, Emma. That one’s poisonous. I can show you some good ones to eat, though. Grandmother Renfrew taught me how to hunt for mushrooms. You have to be really careful which ones you pick, but there should be lots of good ones after this rain.”

Emily scampered through the grass and found what she was looking for. “Look, Emma, these ones are okay, but not those over there.” Emily pointed to individual mushrooms scattered here and there. “Don’t touch those. They’re really deadly. My grandma said you should always pick mushrooms with someone who knows what they’re doing,” Emily warned her friend.

She showed Emma the band of good mushrooms, and both girls were soon spotting them all over the meadow. They picked the spongy morsels, but soon had too many to hold in their hands. The mushrooms were too dirty to wrap in Emma’s apron. That was when Emily remembered the plastic bread bag from her sandwich. She pulled it out of her pocket.

Gazing in amazement at the clear bag, Emma reached out and rubbed the pliable material in her

fingers. “Oooh, what is this?” she squealed, making a disgusted face. Setting the mushrooms on the ground, she held the bag up to her eyes and peered at Emily through it.

While Emma tested the bag with her fingers, Emily tried to explain about plastic and its uses. By the time she was done, both girls were giggling at the distortion the plastic created as they peered through it. When their laughter subsided, they popped the mushrooms into the bag and resumed picking.

As they worked, Emma explained that they had baskets for carrying things and sometimes they used cloth or leather sacks. Soon the girls were discussing the differences between modern inventions and items used in the past. Emma was amazed to hear about television and disc players, and Emily laughed when Emma described having to hand crank a phonograph to hear music recorded on grooved cylinders.

Their talk eventually brought them back to a discussion about wild plants and mushrooms. Emily told Emma how she and her grandmother had harvested mushrooms around the edges of the manure pile after a rain. She told Emma how the little buttons appeared as if by magic overnight and how good they tasted fried fresh in butter with toast. If they were plentiful her grandmother also canned them, but that meant many hours of gathering.

“Sometimes,” she said, standing up and stretching her aching back, “we’d cross the whole meadow and pick them.” Emily sighed, remembering Grandmother Renfrew and their outings together. Oh, how she missed her favourite person.

Squatting on the ground again, Emily glanced down at her sodden runners and realized her feet were thoroughly wet. She should have worn rubber boots. She started giggling again, then tried to explain to Emma how she and her grandmother clomped about in rubber boots after a rain. As Emily demonstrated, both girls burst into fits of laughter, startling a gopher that had poked his head out of a nearby hole.

The girls continued collecting mushrooms until Emily’s bag was full, stopping only occasionally to swat at mosquitoes and dodge the grasshoppers vaulting about them. Or to stand and stretch in the heat of the strong summer sun.

“This is wonderful, Emily. I’ll take these to Granny and we’ll have something different to eat with our stewed rabbit tonight.” Emma held the bag up high and giggled again.

Emily smiled wanly at the thought of eating a poor defenceless wild rabbit. When she considered the options though, she realized there wasn’t a great deal of choice. Emma’s family certainly couldn’t go to a grocery store and stock up on supplies.

“What else do you eat, Emma?” asked Emily, curious now.

“Porridge, every morning, for sure. And oat-cakes or bread. Sometimes wild fowl. You know – ducks, geese, grouse. Once in a while either my father or one of my brothers shoots a deer.”

Emily paled again at the thought of a deer, but realized that even in the 1990s, people hunted them for sport and food.

“We’ve found some wonderful berries to eat too,” Emma added. “Raspberries, and some purplish-black ones like blueberries, although they’re not quite the same as the ones we grew back home. They’re plentiful right now.”

“Can you show me where they are?”

“Sure.”

Both girls ran to the edge of the woods where some bushes hung low to the ground, pulled down by the weight of ripe purple berries.

“Saskatoons! My favourite.” Emily grabbed a handful and popped them into her mouth. The sharp taste of the juicy fruit reminded her instantly of picking berries with Grandmother Renfrew.

Every summer her grandmother had made pies, canned dozens of jars of preserves, and frozen huge quantities to be used over the winter months. The best were fresh berries, heaped with sugar, swimming in fresh farm cream.

Emily felt numb for a moment when she realized her grandmother would never do these things again. In fact, Emily might never do them again either, if the farm really sold. So far she hadn’t been able to come up with a way to convince her family to keep it. Shrugging off the feeling of depression, she hurried after Emma, who had gone around to another side of the bush.

Both girls ate berries until they were full, laughing at their purple-stained tongues and fingers. Then they wandered along the edge of the bluff, where a profusion of wild raspberries grew. They had a handful each, but were too stuffed to eat more. Besides, the mosquitoes were attacking the girls in larger numbers, and they were tired.

“I’ll tell my granny and we’ll come out and pick these later too.”

“What about your mother?” asked Emily. “How is she?”

“Poorly. She’s not regaining her strength like she should. She’s worried, but we are all doing what we can to help.”

“I’m sorry to hear she’s sick.” Emily thought for a few moments. “You know, I remember my grandmother used to say camomile tea was good for almost any kind of ailment. Has your mother tried it?”

“I’ve heard of it back in Scotland, but I didn’t know it grew here too.”

“Sure – it grows wild all over the pasture.” Emily pointed to a plant with her wet sneaker. “It’s just starting to bloom. See? You can pick it and steep it like tea. It can be dried, too.”

“Well, aren’t you wonderful, Emily.”

Emily grinned. “The thanks go to my grandmother. She knew everything about plants and I just listened. She said camomile was great for curing almost anything.”

“Come on, lass. Let’s take this to my home and then we’ll come back with a basket for some of this camomile,” said Emma. She snatched up the bag of mushrooms from the ground where they’d left it and headed into the trees.

The girls hurried up the path and across the clearing to the new building site. Huge clusters of mosquitoes hovered above their heads, causing the girls to flail their arms in the air as they ran. Once they reached the buildings, Emily discovered a huge smouldering fire in the yard, from which billowed clouds of smoke that seemed to be keeping the mosquitoes at bay. All the livestock were pressed against their compound fences, huddling as close as they could to the smudge for relief from the biting pests.

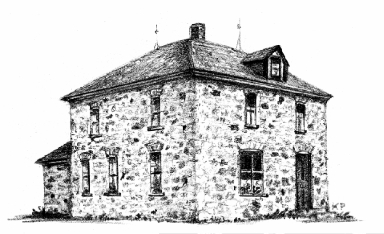

Emily was amazed to find the sod buildings finished. Emma drew her inside the compact house, where she stepped onto a packed dirt floor. Although the interior was dark and damp with thick walls, Emily felt the cosiness of Emma’s new home. The single room was neatly furnished with a wood cookstove, a solitary table, a couple of benches, and a few chairs. A quilt hung across the middle of the room, concealing several cots and beds made up on straw mats on the floor.

The baby, Molly, was asleep in a cradle with netting stretched over the opening, and her mother lay on a bed beside her, looking pale and worn. Emma quietly crossed to a cupboard on the far wall and dumped the mushrooms into a bowl. Then she covered them with a cloth, and tiptoed back out into the sweltering heat of the day with Emily close behind her.

“Mother needs her rest. She’s been up since early morning doing the laundry,” Emma explained as she wadded up the plastic bag and handed it back to Emily.

Emily tucked it into her pants pocket. “Guess you’d have a hard time explaining this, wouldn’t you?”

Emma grinned. “Come on, I’ll show you the garden.”

Emily couldn’t believe her eyes at the size of the plants, but when she thought about it, she realized over a month had passed in Emma’s time. Bella was in the garden again, this time directing the younger children on how to pull weeds. She waved at Emma and asked her to bring a bucket of water to the thirsty crew.

Emily followed Emma through a stand of poplars, where they found a wooden pail turned upside down over a plank lid. The handle of the pail was tied to a rope. Emma heaved the solid lid up and threw it aside with a thunk, then dropped the bucket into the deep dark hole. Emily could hear the splash when it hit water. Emma jerked the rope until the pail sank, struggled to pull the heavy load back up again, then grabbed a dipper hanging on a nearby tree. As she hauled the bucket back to the garden, the water sloshed onto her feet and the hem of her dress, but she didn’t seem to mind.

“Tell me who everyone is,” Emily asked, as they walked along.

“All right,” said Emma. “You already know Bella – Isabella, really. She’s 17 – my oldest sister. The younger ones are Elsbeth – Beth for short, she’s named after my mother, and Katherine, although we call her Kate. She’s the serious one of the bunch.”

Emily laughed. “There must be something about the name Kate. That’s my mother’s name and she’s always serious, too.”

By now the girls had reached the edge of the garden and the others came running for a drink. Bella poured some of the water into a crockery jug for later and suggested Emma take the remaining water to the men working in the field. Then the sisters went back to hoeing.

“Come on,” said Emma. “Now I can introduce you to the rest of my family. You’ve already seen Grandma and Geordie. He’s named after my dad.”

“Where are they?”

“Oh, Granny is probably collecting eggs and feeding the chickens. She’s partial to them. She says ‘if you treat them well, they’ll lay better for you.’ It’s worked so far.” Emma laughed. “Geordie’s probably gone fishing, or getting into trouble somewhere.”

They ducked under the rope clothesline where the laundry was flapping in the wind between two trees, and followed a narrow trail through some scraggly bush. In the clearing ahead Emily could see a man struggling behind a plough and oxen, his shaggy grey hair matted to his neck under his wide-brimmed hat, and a much younger man tugging on the harness of the balking pair of animals. Sweat was pouring off both the men and the huge beasts. The oxen switched their tails frantically to keep the clusters of mosquitoes and flies off their bodies.

“There’s my dad, working up some new land. That’s Sandy wrestling with the oxen. He’s the oldest of us kids. And there’s Duncan and Jack.” She pointed to two figures at the bottom of the field, one wielding an axe, the other dragging roots over to a pile at the edge of the clearing.

The girls stood watching the scene for a few moments. Emily wiped the sweat from her own forehead and swatted at little flies. How could they work in this heat and with all these bugs? She could hardly stand it, especially when the grasshoppers suddenly whirred and flew up at her. They reminded her of the summer she’d ridden her bike frantically to the potato patch every day with her eyes closed most of the time, while surges of the leaping insects pelted her from all directions.

All at once they heard some loud bellowing from the oxen. The men shouted to each other through the din. Emma’s dad was yanking on the reins, while Sandy used a switch to try to keep the oxen from dashing off. But there was no stopping the animals. They jerked the reins out of the men’s hands. Duncan and Jack came racing up the field, yelling and waving their arms to head them off, but the cattle made right for a nearby slough, dragging the plough behind them. They didn’t halt until they were standing belly deep in the water, where they drank their fill between bellows.

Emily heard a great deal more cussing from the men, as they discussed how to retrieve the oxen and plough, but by the time the girls arrived at the banks of the slough the men were laughing. Duncan and Jack had waded into the water and were splashing each other, while Sandy was yanking on the harness, trying to persuade the animals to come back to shore. Emma’s dad was leaning against a tree swatting at the horseflies with his shirt, which he had removed moments before. His face was creased with streaks of dirt and moisture.

“Hello, lass. You’ve come at a good time,” he said in a thick marbly voice as they approached. A stocky, muscular man with red streaks in his greying beard, he gave Emma a wide grin, and Emily could see how Geordie resembled him. “Drat those oxen. They’ll not get the better of me and my boys,” he laughed, as he shook his fist at them.

He appeared not to see Emily, and she was glad he couldn’t. She and Emma would have a great deal of explaining to do. Besides, it was kind of fun being invisible to people.

Plunging the dipper into the pail of water, Emma’s dad took a long drink, and poured the rest over his bare head. Then Emma gave him his hat, which had flown off in the chase. By now Sandy had the oxen up on the bank, and the others were walking over for a drink of water from the pail Emma had brought.

Sandy was laughing as he joined them. “That was quite a tussle. Did you see how determined they were?”

Emily clutched her sides with laughter as he acted out the scene again, exaggerating the movements of everyone chasing after the runaway animals. Sandy, although he obviously was strong, was tall and thin, more like his mother. Emily found it hard to believe, when she saw him up close, that he had been able to handle the powerful oxen as well as he had.

Duncan and Jack, rivulets of water streaked through the dust and sweat on their faces, seemed more likely to be the ones that could manage the beasts. They were both sturdy, husky young men. Duncan was bearded like his father and brother Sandy, but Jack was dark-haired and smooth-faced, younger than the others. He looked more serious too.

He seemed anxious to get back to work, and once they’d all had their fill of water, he was the first to return to the field. The oxen were more subdued, but still bawling as they were led back to the plough.

The girls trailed behind the men, and Emma left the pail of water for them in a shaded spot under a tree. Neither of the girls noticed Geordie hidden in the branches above. Nor did they hear him jump down and follow them as they headed back to the rock.

Emma and Emily stopped briefly at the house for a basket, and then hurried through the bluff to the meadow where the boulder stood. There they gathered some camomile. Emily carefully explained to Emma how to brew the tea for her mother, even though Emma thought her granny would know how to do it.

Before they parted at the rock, Emma gave Emily a quick hug. “Thanks for a fine day, lass.”

“Thank you,” Emily replied. She could feel a happy glow on her face as she stood for a few moments watching Emma disappear through the trees. Now she knew what was meant in Anne of Green Gables about kindred spirits.

Suddenly Emily realized how incredibly late she must be. Just before she popped the special stone in its hiding place, she thought she caught a movement out of the corner of her eye. But she quickly dismissed it and sped for home. And not until she was turning the knob on the porch door, did she realize she’d forgotten to ask Emma her last name.