O n November 22, 1963, one of history’s ultimate triangulations occurred, stretching from Dallas, through Cuba, to Paris. In Dallas Lee Harvey Oswald fired the shot that fatally wounded President Kennedy. Simultaneously, in Cuba French journalist Jean Daniel lunched with Fidel Castro, a day after an all-night interview during which Daniel had delivered a conciliatory message from Kennedy. And in Paris, Nestor Sanchez, a CIA case officer, offered a poison pen device for use in a plot against Castro to Rolando Cubela, a disaffected Cuban military officer.

Kennedy’s death that day, and the combination of circumstances surrounding it, created a cottage industry of conflicting conspiracy theories, which still thrives today despite—and in part because of—the Warren Commission’s finding that Oswald acted alone. But there are still those who remain convinced that Kennedy was killed by Cuban agents in retaliation for ongoing U.S. efforts to overthrow or assassinate Castro. Others are just as convinced the killing was a plot by disgruntled Mafia, antiCastro Cuban exiles, and/or renegade CIA agents angered by Kennedy’s handling of the Cuba issue. These are theories fed—depending on the point of view—by the documented evidence of, on one hand, ongoing CIA and Mafia attempts to kill Castro and, on the other, Kennedy’s failure to remove him with the Bay of Pigs invasion or during the missile crisis coupled with secret tentative steps toward rapprochement that he made before his assassination.

Both “tracks”—covert action and accommodation—continued after Kennedy’s death, but slowly withered away under President Johnson’s increasing preoccupation with Vietnam, his distaste for the Kennedy brothers’ obsession with Castro and Cuba, and his particular antipathy toward Bobby Kennedy.

The fitful steps toward rapprochement continued over a period of about two years, beginning in early 1963 and effectively ending in late 1964, although declassified documents indicate Castro wanted to talk again as late as April 1965. One of the most comprehensive accounts of the failed effort at detente appeared in the October 1999 edition of Cigar Aficionado. 1 Written by Peter Kornbluh, a senior analyst at the nonprofit National Security Archive in Washington, the article drew from declassified documents obtained under the Freedom of Information Act. The 1963-64 time frame of the rapprochement effort does not include the ballyhooed secret meeting between Kennedy aide Richard Goodwin and Che Guevara during an August 1961 hemisphere meeting in Punta del Este, Uruguay. Castro told a Havana audience, which included Goodwin, during an October 2002 international conference on the missile crisis that he had not even been aware of the Goodwin-Guevara meeting until after the fact. 2 Goodwin, it should be noted, was one of the principal architects of Operation Mongoose, planning for which was already under way at the time of his meeting with Guevara.

The CIA’s involvement in Castro assassination plots extended over a lengthier period, from August 1960 to June 1965. The 1976 Church Committee report revealed “concrete evidence of at least eight plots involving the CIA to assassinate Fidel Castro” during the 1960-65 period, but it went on to say 3 it found no conclusive evidence that Eisenhower, Kennedy, or Johnson, the three presidents in office during that period, had knowledge of the assassination plotting. Whether they did or not remains a point of considerable speculation. Many agency people were convinced that, at the least, Bobby Kennedy knew of the plots, and most probably President Kennedy did as well. Kennedy loyalists, including Arthur Schlesinger, were just as adamant that neither of the Kennedys was aware of the assassination schemes. Some questions remain about Eisenhower’s possible knowledge of plots on his watch, but it seems clear that Johnson did not know.

New York attorney James Donovan had just returned from another trip to Havana, where he had met with Castro again on January 25, 1963, this time in an effort to negotiate the release of twenty-two U.S. citizens still imprisoned in Cuba. A month earlier, Donovan, fronting as the lawyer

for a private citizens’ committee—but in reality a behind-the-scenes U.S.government negotiator directed by Bobby Kennedy—had successfully gained freedom for the 1,113 Bay of Pigs invasion brigade members still jailed in Cuba in exchange for a $53 million ransom in food and medicines. And it was more than three months after the missile crisis agreement that enraged Castro because of the Soviets’ unilateral decision to withdraw the missiles.

On January 26, 1963, Bob Hurwitch, Donovan’s State Department contact, recorded in a memorandum for the files what he described as Donovan’s “most cordial and intimate meeting to date” with Castro. Comandante Rene Vallejo, Castro’s personal physician and confidante who had trained at Massachusetts General Hospital in Boston, served as interpreter. At one point, Hurwitch noted, “during an impromptu visit to a medical school, Castro led 300 medical students in chanting, ‘Viva Donovan.’ ”

According to the Hurwitch memo, “Donovan told Castro his difficulties lay in his dependence on the Soviets. Castro only grunted in reply.” But the final two items of the nine-point memo must have been what really caught Washington’s attention. They read:

8. At the airport just before Donovan’s departure, Vallejo broached the subject of re-establishing diplomatic relations with the U.S.

9. Castro warmly re-issued the invitation that Donovan return to Cuba with his wife for a week or so (possibly the first week in March). Castro indicated he wanted to talk at length with Donovan about the future of Cuba and international relations in general. 4

Two days later, Sterling Cottrell sent a copy of the Hurwitch memo to Secretary of State Dean Rusk, along with a covering memo telling Rusk that CIA Director John McCone had similar information. When the president was given the information, he responded that it “looked interesting.” 5 As Donovan prepared to return to Havana in early March, Gordon Chase, an aide to Bundy, the president’s assistant for national security, wrote in a memo to his boss that Hurwitch had suggested Donovan tell Castro: “As far as I understand U. S. policy, only two things are nonnegotiable, (1) Cuba’s ties with the Sino-Soviet Bloc and (2) Cuba’s interference with the hemisphere.” Bundy responded to Chase three days later, “The President does not agree that we should make the breaking of Sino/ Soviet ties a non-negotiable point. We don’t want to present Castro with

a condition that he obviously cannot fulfill. We should start thinking along more flexible lines. The above must be kept close to the vest. The President, himself, is very interested in this one.” 6

Donovan was back in Havana in early April. The CIA debriefed him after his return to Washington. McCone, in an April 10 memo to President Kennedy, reported: “The main thrust of Donovan’s discussion [with Castro] . . . was political and can best be evaluated by Doctor Vallejo, a close personal advisor of Castro who was present at the meetings. Vallejo said Castro knew that relations with the United States are necessary and Castro wanted these developed. However, there are certain Cuban Government officials, communists, who are strongly opposed, even more than certain people in the United States. These officials are under close surveillance. They have no great following in Cuba; but if they rebelled at this time, Cuba would be in chaos. He believed that Donovan and Castro could work out a plan for a reasonable relationship between the two countries.” McCone concluded by noting “Donovan has the confidence of Castro, who believes Donovan is sincere with no official ties to the United States Government.” 7 President Kennedy met privately with McCone the same day, expressing great interest in McCone’s memo and “raised questions about Castro’s future within Cuba, with or without the Soviet presence. McCone said the matter was under study and he proposed to send Donovan back on April 22 to secure freedom of the remaining prisoners and also keep the channel of communication open.” 8

McCone returned to the subject in another memorandum five days later, suggesting Castro had a dilemma with how to proceed in reaching an accommodation with the United States. “Castro’s talks with Donovan have been mild in nature, conciliatory and reasonably frank,” wrote McCone. “Of greater significance is Dr. Vallejo’s private statements to Donovan that Castro realizes he must find a rapprochement with the United States if he is to succeed in building a viable Cuba. Apparently Castro does not know how to go about this, therefore the subject has not been discussed with Donovan.” 9

Castro soon found a way in Lisa Howard, an assertive and tenacious ABC News reporter who scored a major coup by obtaining an interview with the Cuban leader. The April 22 interview didn’t air until May 10, but Richard Helms, then head of the CIA’s clandestine services, recorded her observations from CIA debriefings in a three-page memorandum, dated May 1, to McCone on the subject: “Interview of U.S. Newswoman

with Fidel Castro Indicating Possible Interest in Rapprochement with the United States.” 10

“It appears,” wrote Helms, “that Fidel Castro is looking for a way to reach rapprochement with the United States Government, probably because he is aware that Cuba is in a state of economic chaos. Castro indicated that if a rapprochement was wanted President John F. Kennedy would have to make the first move.” Helms offered an early indication of what a mixed blessing the Howard connection became for Kennedy administration officials dealing with the issue. His memo concluded: “Liza [sic] Howard definitely wants to impress the U.S. Government with two facts: Castro is ready to discuss rapprochement and she herself is ready to discuss it with him if asked to do so by the U.S. Government.”

The next day Marshall Carter, deputy CIA director, sent a memo to Bundy on behalf of McCone, who was out of town, cautioning “about the importance of secrecy in this matter,” adding that McCone “feels that gossip and inevitable leaks with consequent publicity would be most damaging. He suggests that no active steps be taken on the rapprochement matter at this time . . . and that in these circumstances emphasis should be placed in any discussions on the fact that the rapprochement track is being explored as a remote possibility and one of several alternatives involving various levels of dynamic and positive action.” 11

A month later, on June 5, Helms followed up with another memo about numerous signals indicating Castro’s desire for rapprochement. The following day the Special Group discussed “various possibilities of establishing channels of communication to Castro.” Members agreed it was a “useful endeavor,” but took no action. 12

Little apparently happened until September 1963. William Attwood, a onetime journalist-turned-diplomat then working as an adviser with the UN delegation, volunteered his services—aided and abetted by Lisa Howard, an old journalistic acquaintance—in advancing the cause of rapprochement. Attwood’s offer led to the most intensive period of the rapprochement effort, marked by more enthusiasm on the part of Howard and Attwood than the administration. At the suggestion of Averill Harriman, 13 undersecretary of state for political affairs, Attwood wrote a memo proposing “a discreet inquiry into neutralizing Cuba on our terms. It is based on the assumption that, short of change of regime, our principal political objectives in Cuba are: a. The evacuation of all Soviet bloc military personnel, b. An end to subversive activities by Cuba in Latin America, c. Adoption by Cuba of a policy of non-alignment.”

The best time to begin that “discreet inquiry,” suggested Attwood, was the upcoming session of the UN General Assembly and he was the one to do it. “As a former journalist who spent considerable time with Castro in 1959, I could arrange a casual meeting with the Cuban Delegate, Dr. [Carlos] Lechuga. This could be done socially through mutual acquaintances [Lisa Howard],” Attwood wrote. “I would refer to my last talk with Castro, at which he stressed the desire to be friends with the U.S., and suggest that, as a journalist, I would be curious to know how he felt today. If Castro is ready to talk, this should provide sufficient reasons for Lechuga to come back to me with an invitation.” Attwood then cited three reasons why he “should undertake this mission.” 14

The memo wound up first with Stevenson, then with Harriman. Stevenson said he liked the idea and offered to take it up with the president, adding, “Unfortunately, the CIA is still in charge of Cuba.” Harriman said he was “adventurous enough” to be interested and urged Attwood to see Bobby Kennedy. Harriman’s suggestion resulted in a September 24 meeting with Bobby Kennedy. In the meantime, Attwood had spoken with President Kennedy and “got his agreement to go ahead with the initiative.” But “for some reason Stevenson was not keen on my seeing Robert Kennedy, but I trusted Harriman’s instincts. Bob had been deeply involved in our Cuban relations and would expect to be consulted about this gambit; also, he had his brother’s ear as did no one else.”

By the time of his September 24 meeting with Bobby Kennedy, Attwood had already spoken with Lechuga informally at Lisa Howard’s cocktail party. Lechuga suggested it might be useful for Attwood to go to Havana, but Bobby Kennedy thought a visit to Havana “was too risky—it was bound to leak—and if nothing came of it the Republicans would call it appeasement and demand a congressional investigation. But he thought the matter was worth pursuing at the U.N. and perhaps even with Castro some place outside Cuba.”

The maneuvering continued with contacts between the eager Howard and Attwood on the one side and Lechuga and Rene Vallejo on the other. Bundy told Attwood that Gordon Chase, one of Bundy’s deputies, would be his contact at the White House. Vallejo contacted Howard, telling her that Castro “would like a U.S. official to come and see him alone” and offered to send a private plane to Mexico to fly the official to a private airport near Varadero. 15 On November 5 the subject came before the Special Group, which “thought it inadvisable to allow Mr. Attwood, while on the UN staff, to get in touch with Castro.” Helms suggested “it might be

possible to ‘war game’ this problem and look at it from all possible angles before making any contacts.” A week later Bundy told Attwood to inform Vallejo “it did not seem practicable to us at this stage to send an American official to Cuba and that we would prefer to begin with a visit by Vallejo to the U.S. where Attwood would be glad to see him and listen to any messages he might bring from Castro.” Bundy also noted that without any indication of a willingness by Cuba to make some policy changes “it is hard for us to see what could be accomplished by a visit to Cuba.” 16 Attwood finally spoke directly with Vallejo by telephone on November 18 from Howard’s apartment. Vallejo said he was not able to come to New York but instructions would be sent to Lechuga to discuss “an agenda” for a later meeting with Castro. 17 Chase reported the conversation in a memo to Bundy the following day and concluded by noting “the ball is now in Castro’s court.” 18 On November 18, the day Attwood spoke with Vallejo, Kennedy gave a speech in Miami on Cuba’s future. In the speech Kennedy said Cuba had become “a weapon in an effort dictated by external powers to subvert the other American republics. This and this alone divided us. As long as this is true, nothing is possible. Without it, everything is possible.” Arthur Schlesinger Jr., who helped draft the speech, said later that Kennedy’s language was intended to convey to Castro the real potential for normalization between the United States and Cuba. 19

If that was the intended message, Rolando Cubela, the disaffected Cuban military officer code-named AMLASH, received a different message. He was meeting in Paris with Nestor Sanchez, his CIA case officer, when Kennedy was killed in Dallas. “At that meeting,” said a U.S. Senate Committee report, “the case officer referred to the President’s November 18 speech in Miami as an indication that the President supported a coup. That speech described the Castro government as a ‘small band of conspirators’ which formed a ‘barrier’ which ‘once removed’ would ensure United States support for progressive goals in Cuba. The case officer told AMLASH that FitzGerald had helped write the speech.” 20

With Kennedy’s assassination, said Attwood, “the Cuban exercise was quietly laid to rest by our side.” 21 It may have been put on hold, but it was not yet laid to rest. On November 25 Chase offered his thoughts in a memo to Bundy, saying Attwood’s “Cuban exercise is still in train” but “events of November 22 would appear to make accommodation with Castro an even more doubtful issue than it was. While I think that President Kennedy could have accommodated with Castro and gotten away with it with a minimum of domestic heat, I’m not so sure about President

Johnson” who “would probably run a greater risk of being accused, by the American people, of‘going soft.’ In addition, the fact that Lee Oswald has been heralded as a pro-Castro type may make rapprochement with Cuba more difficult—although it is hard to say how much more difficult.” 22

Chase offered three alternative courses for Attwood, and recommended that if Lechuga called Attwood to arrange a meeting, “Attwood should schedule such a meeting for a few days later and call us immediately. However, if Lechuga does not call him, Attwood should take no initiative until he hears from us.”

If this course was decided on, said Chase, “the sooner the better. In view of his [Attwood] and [Adlai] Stevenson’s activist tendencies in this matter, they will approach him and assure him that we feel the same way and that we are still prepared to hear what Castro has on his mind. . . . While November 22 events probably make accommodation an even tougher issue for President Johnson than it was for President Kennedy, a preliminary Attwood-Lechuga talk still seems worthwhile from our point of view—if the Cubans initiate it.”

In a second memo to Bundy the same day, Chase raised the question of Lisa Howard’s role and suggested it was a good time to ease her out of the picture. “Her inclusion at every step so far, frankly, makes me nervous.” 23

Meanwhile, Lechuga told Lisa Howard he had received authorization from Castro to meet with Attwood and “wondered whether things were still the same.” Chase reported in a December 2 memo to Bundy: “The ball is in our court; Bill [Attwood] owes Lechuga a call. What to do?” 24

Chase followed up the next day with another memo to Bundy recommending Attwood meet with Lechuga and hear what he had to say. He cautioned “complete discretion,” adding “in this regard, we are glad that Lisa Howard is now out of the picture. She should be given no intimation that further U.S. contact is taking place.” Chase also suggested delivering a tough message to Cuba along the lines of “if you don’t feel you can meet our concerns, then just forget the whole thing; we are quite content to continue on our present basis.” He wondered if Attwood was “the man to convey the message”; then he concluded the UN adviser probably was good enough but would benefit from “a good, stiff brainwashing and education in Cuban affairs before he meets with Lechuga.” 25

Chase’s recommendation to meet with Lechuga was overruled. On December 4, according to Attwood, “Lechuga approached me in the Del

egates’ Lounge to say he had a letter from Fidel himself, instructing him to talk with me about a specific agenda. I called Chase, who replied all policies were now under review and be patient. . .. On the twelfth, I told Lechuga to be patient and that so far as I knew, we weren’t closing the door. Neither of us knew then that it would be six years before we would meet again—in Havana.”

President Johnson, while visiting the U.S. delegation to the UN on December 17, told Attwood at lunch that “he had read my chronological account of our Cuba initiative ‘with interest.’ And that was it. I was named ambassador to Kenya in January, and during my Washington briefings I saw Chase, who told me there was apparently no desire among the Johnson people to do anything about Cuba in an election year.”

Attwood wrote in his 1987 book that it “seems pointless to raise” what part “our Cuban gambit” played in Kennedy’s assassination; then he promptly raised it, hinting at a possible role by the CIA, frustrated Cuban exiles, and other adventurers “like Frank Fiorini, alias Frank Sturgis.” 26

Even with Attwood gone, the irrepressible Lisa Howard wouldn’t let the issue of accommodation disappear. Returning from another reporting assignment in Cuba, she carried a “verbal message” from Castro to President Johnson, which began, “Please tell President Johnson that I earnestly desire his election to the Presidency in November” and “if there is anything I can do (aside from retiring from politics), I shall be happy to cooperate.” The message continued, “if the President feels it necessary during the campaign to make bellicose statements about Cuba or even to take some hostile action—if he will inform me, unofficially, that a specific action is required because of domestic political considerations, I should understand and not take any serious retaliatory action.” Castro said he hoped to resume the dialogue begun by Attwood. He realized that “political considerations may delay this approach until after the November elections.” But, he said he did not see any areas of contention that “cannot be discussed and settled within a climate of mutual understanding.

This hostility between Cuba and the United States is both unnatural and unnecessary—and it can be eliminated.” 27

Howard was insistent upon delivering the message personally to President Johnson. Bundy and Chase were just as adamant that she not deliver it, and to make sure, Bundy circulated a blunt internal memo to seven White House aides he thought Howard might try to approach. It read:

A newspaperwoman named Lisa Howard is back from a long trip to Cuba

and says she has a personal message from Castro for the President. She is

an extraordinarily determined and self-important creature and will undoubtedly knock at every door we have at least five times. It is quite impossible that she can see Castro and the President without writing about her peacemaking efforts at some stage, and I see nothing whatever to be gained by letting her play this game with us.

My impression is that it took her six weeks to get past Castro’s defenses, and the question is whether we can do better.

I should add that Miss Howard has been offered every opportunity to report her findings and information to an appropriate officer of the Government. Her determination to give her message only to the President is all that prevents her from completing her letter-carrier’s task. 28

Howard never managed to get through the White House defenses, although she compensated by later enlisting the support of Adlai Stevenson, much to the consternation of Bundy and Chase.

Chase, in a memo to Bundy, noted “the latest developments add at least two new factors to the situation which make Lisa Howard’s participation scarier than it was before. One, for the first time during the Johnson Administration, Lisa has been used to carry a message from the U.S. to Cuba. Before this, the Johnson Administration had relatively little to fear from Lisa since, essentially, we were just listening to her reports on and from Castro. Two, Lisa’s contact on the U.S. side is far sexier now [Stevenson], than at any time in the past [Attwood and Chase].” Chase then made it clear he favored removing Howard “from direct participation in the business of passing messages.” 29

Other efforts throughout 1964 to restart the rapprochement dialogue—mostly initiated by Cuba and all unsuccessful—included one with the Spanish government acting as intermediary; a Castro interview with New York Times correspondent Richard Eder, which the State Department’s Bureau of Intelligence and Research called Cuba’s “strongest bid to date for a U.S.-Cuban rapprochement”; and a plan to approach Che Guevara, through a British intermediary, when Guevara visited the UN in December of that year. 30

What may have been a final Cuban effort came in April 1965, when Celia Sanchez, Castro’s longtime companion, called Donovan and “told him that Castro would like to talk to him. Castro asked if Donovan would come down to Cuba. There appeared to be some urgency . . . the ball is now with State.” State’s proposed response—which Bundy okayed—was to have Donovan call Sanchez back and tell her that he was busy and

needed to have more information before he could make it to Havana. There is no indication the overture progressed further. 31 Castro did manage to get the Johnson administration’s attention five months later when Cuba opened the tiny north coast port of Camarioca for a mass exodus of some 5,000 refugees to the United States, a prelude of what was to come with Mariel in 1980. Camarioca led to the December 1965 initiation of the so-called Freedom Flights, an organized flow that brought nearly 300,000 refugees from Cuba to the United States over the next seven years.

As tentative steps toward accommodation were under way, so were plots to assassinate Castro, as detailed in two key documents: The Church Committee’s Alleged Assassination Plots Involving Foreign Leaders, published in 1975 and the CIA Inspector General’s 1967 Report on Plots to Assassinate Fidel Castro, declassified in 1993.

Although the Church Committee reported it found evidence of “at least eight plots” by the CIA to assassinate Castro, it agreed that some of the plots “did not advance beyond the stage of planning and preparation.” 32 It also qualified its findings by acknowledging that “the plots against Fidel Castro personally cannot be understood without considering the fully authorized, comprehensive assaults upon his regime, such as the Bay of Pigs invasion in 1961 and Operation MONGOOSE in 1962.” 33

In fact, two of the three most substantive efforts aimed at Castro’s assassination—both involving the Mafia—coincided with the Bay of Pigs planning and Mongoose. Both assassination plots were closely held separate tracks, unknown to most of the participants in the Bay of Pigs and Mongoose. As recorded earlier, Jake Esterline, the CIA’s Cuba Project chief, learned only accidentally of the first Mafia assassination plot when he refused to authorize funds without being told what they were financing. The second major attempt was essentially a resurrection—or continuation—of the first Mafia-related effort.

A third serious attempt involving assassination centered on Rolando Cubela, a rebel student leader who had fought against Batista. Cubela had some experience in assassinations, reportedly having been involved in the assassination of Batista’s military intelligence chief in 1956. 34 Regarded by many as somewhat unstable, Cubela had an intermittent relationship with

the CIA from 1961 through June 1965. The CIA contended that the agency’s relationship with Cubela involved a coup attempt that was not designed as an assassination, although they also acknowledged that Castro could have died during the coup. Cubela’s two successive case officers testified before the Church Committee that Cubela was never asked to assassinate Castro, but Cubela believed assassination to be the first step in a coup. “Both officers were clearly aware of his desire to take such action,” said the Church Committee. 35

The Senate committee report as it related to plots against Castro relied heavily on the detailed CIA inspector general’s investigation ordered eight years earlier by then CIA Director Richard Helms in response to a column by Drew Pearson that appeared in newspapers on March 3, 1967. The column began: “President Johnson is sitting on a political H-bomb— an unconfirmed report that Sen. Robert Kennedy may have approved an assassination plot which then possibly backfired against his late brother.” 36

The apparent source of the story was Edward Morgan, an attorney for John Rosselli, a key mob figure in both Mafia-linked plots to kill Castro. After the column appeared, President Johnson asked the FBI to interview Morgan, who hinted at Castro’s involvement in President Kennedy’s assassination. Johnson received the FBI report on March 22, the same day he happened to be meeting with Helms. He asked Helms for a detailed account of the CIA’s plots to assassinate Castro. Helms ordered Jake Earman, the CIA’s inspector general, to do the report. The completed report was delivered to Johnson on May 10, 1967. 37 “We were running a damn Murder Incorporated in the Caribbean,” Johnson told an interviewer in 1971. 38

11 It became clear very early in our investigation that the vigor with which schemes were pursued within the Agency to eliminate Castro personally varied with the intensity of the U.S. Government’s efforts to overthrow the Castro regime,” the IG [inspector general’s] report noted. “We can identify five separate phases in Agency assassination planning, although the transitions from one to another are not always sharply defined. Each phase is a reflection of the then prevailing Government attitude toward the Cuban regime.” 39

The five phases cited were:

a. Prior to August 1960: All of the identifiable schemes prior to about

August 1960, with one possible exception, were aimed only at discrediting

Castro personally by influencing his behaviour or by altering his appearance.

b. August 1960 to April 1961: The plots that were hatched in late 1960 and early 1961 were aggressively pursued and were viewed by at least some of the participants as being merely one aspect of the over-all active effort to overthrow the regime that culminated with the Bay of Pigs.

c. April 1961 to late 1961: A major scheme that was born in August was called off after the Bay of Pigs and remained dormant for several months, as did most other Agency operational activity related to Cuba.

d. Late 1961 to late 1962: That particular scheme was reactivated in early 1962 and was again pushed vigorously in the era of Project MONGOOSE and in the climate of intense administration pressure on CIA to do something about Castro and his Cuba.

e. Late 1962 until well into 1963: After the Cuban missile crisis of October 1962 and the collapse of Project MONGOOSE, the aggressive scheme that was begun in August 1960 and revived in 1962 was finally terminated in 1963, but both were impracticable and nothing ever came of them.

The report added: “We cannot overemphasize the extent to which responsible Agency officers felt themselves subject to the Kennedy administration’s severe pressures to do something about Castro and his regime. The fruitless, and in retrospect, often unrealistic plotting should be viewed in that light.”

Interestingly, the Cubela connection was cited as part of the IG’s report on assassination plots against Castro, even though agency officials testified before the Church Committee that they did not consider it an assassination plot. Cubela’s ongoing ties with the agency—and subsequent involvement with a U.S.-funded exile operation headed by Manuel Artime—are explored further in chapter 13.

The IG report made no mention of what the Church Committee called “the first action against the life of a Cuban leader sponsored by the CIA” in July 1960. A Cuban working with the agency in Havana had told his case officer he expected to be in touch with Raul Castro. The Havana Station cabled headquarters and field stations the night of July 20, inquiring about intelligence needs that might be met during the contact. The headquarters duty officer contacted both Tracy Barnes, [Bissell’s deputy] and Col. J. C. King. Based on their instructions, the headquarters duty officer cabled back a response on July 21 saying, “Possible removal top three leaders is receiving serious consideration at HQS,” and asked

ACCOMMODATION OR ASSASSINATION

whether the Cuban was sufficiently motivated to risk “arranging an accident” involving Raul Castro. A $10,000 payment was authorized “after successful completion.” The cable was signed “by direction of J. C. King,” who had previously suggested “elimination” of Castro. Soon after, another cable arrived in the Havana Station, signed by Barnes, telling the case officer to “drop the matter.” The Cuban had already gone to contact Raul Castro. He returned soon thereafter, saying he had not had the opportunity to arrange an accident. 40

Only a month later, in August 1960, Bissell met with Sheffield Edwards, the CIA’s security director, setting in train the first Mafia-linked effort to assassinate Castro. Edwards turned to Robert Maheu, an ex-FBI agent who had done work for the CIA in the past, to find a Mafia contact. Maheu, authorized by his “clients” to pay $150,000 for Castro’s removal, came up with John Rosselli, who in turn, enlisted Sam Giancana. Both Rosselli and Giancana declined payment. Santos Trafficante, another Mafia figure with ties to Havana, was brought into the plot later. So was Tony Varona, a Cuban exile who, coincidentally, happened to be a member of the exile front group created for the Bay of Pigs invasion. James O’Connell, head of the CIA security office’s support division, became the CIA case officer for the operation. As of late September, only Bissell, Edwards, and O’Connell were aware of the plot to use gangster elements to assassinate Castro.

About this time Edwards, with Bissell present, briefed CIA Director Allen Dulles and his deputy, Gen. Charles Cabell, “on the existence of a plot involving members of the syndicate. The discussion was circumspect; Edwards deliberately avoided the use of any ‘bad words.’ The descriptive term used was ‘an intelligence operation.’ ” Edwards was to tell the IG investigators, however, that he was sure Dulles and Cabell both understood the nature of the operation.

Small poison pills became the eventual assassination weapon of choice. The first batch, prepared by the CIA’s Technical Services Division, wouldn’t dissolve in water, so a new batch was made. The second batch of pills then went from O’Connell, to Rosselli, to Trafficante, and then, apparently, to Juan Orta, who worked in Castro s office. But Orta got “cold feet,” according to the gangsters. In fact, Orta already had fallen from favor and lost his access to Castro. He was to take asylum in the Venezuelan embassy a week before the Bay of Pigs. When Orta failed to make contact with Castro, Trafficante put the plotters in touch with the controversial and ambitious Varona, who claimed to have a contact inside

THE CASTRO OBSESSION

a restaurant frequented by Castro. Money and pills were delivered to Varona, but no one seems to know whether the pills ever got to Cuba. If they did, they never made it to Castro. Edwards, according to the IG’s report, “is sure there was a complete stand down after that; the operation was dead and remained so until April 1962. He clearly relates the origins of the operation to the upcoming Bay of Pigs invasion, and its termination to the Bay of Pigs failure.” Others involved suggested, however, that it remained an ongoing, but temporarily sidetracked operation.

Whatever the case, the Mafia-linked plot was resurrected, this time with Rosselli and Varona playing the key roles without the participation of Giancana and Trafficante. The CIA’s intrepid Bill Harvey was now the man in charge and was to run it as part of a larger CIA “Executive Action” program known as ZR/RIFLE.

“The Inspector General’s Report divides the gambling syndicate operation into Phase I, terminating with the Bay of Pigs, and Phase II, continuing with the transfer of the operation to William Harvey in late 1961,” according to the Church Committee. “The distinction between a clearly demarcated Phase I and Phase II may be an artificial one, as there is considerable evidence that the operation was continuous, perhaps lying dormant for the period immediately following the Bay of Pigs.” 41

While the Church Committee and IG reports differed in some lesser details—in part because the Church Committee had the IG’s report to work with and testimony from a wider range of people—the broader outlines are the same in both accounts.

Bissell asked Harvey in early 1961, well before Harvey became involved with Cuba, to establish a general capability, which became known as Executive Action, within the CIA for “disabling foreign leaders, including assassination as a ‘last resort.’ ” ZR/RIFLE became the cryptonym. “Harvey’s notes reflect that Bissell asked him to take over the gambling syndicate operation from Edwards and that they discussed the application of ZR/RIFLE program to Cuba’ on November 16, 1961.” Bissell didn’t dispute that in his testimony to the Church Committee but said the operation “was not reactivated, in other words, no instructions went out to Rosselli or to others... to renew the attempt, until after I left the Agency in February 1962.” Richard Helms succeeded Bissell as head of the agency’s clandestine operations.

In early April 1962 Harvey asked Edwards, on “explicit orders” from Helms, to put him in touch with Rosselli. By this time Operation Mongoose was well under way, and Harvey headed Task Force W, the CIA

Jake Esterline, the Central Intelligence Agency’s (CIA) project director for what became the Bay of Pigs invasion, takes a break at the agency’s old offices in temporary buildings adjacent to the reflecting pool below the Lincoln memorial in Washington. Jake Esterline

Esterline (left) became a guerrilla warfare expert with the Office of Strategic Services (OSS) during World War II. He was sent to the China-Burma theater of war to train guerrillas to fight the Japanese. Here Esterline is pictured at a guerrilla camp in Tengchung, China, with an unidentified visiting correspondent. This experience, coupled with later postings in the CIA’s Western Hemisphere Division, made him a natural choice to be one of the chief planners for operations against Cuba. Jake Esterline

Marine colonel Jack Hawkins, paramilitary chief and amphibious operations expert for the Bay of Pigs invasion, is pictured here circa 1956. Hawkins was captured and imprisoned in the Philippines by the Japanese during the early stages of World War II. He later escaped and worked with Filipino guerrillas in Mindanao before his exfiltration to Australia by submarine. Jack Hawkins

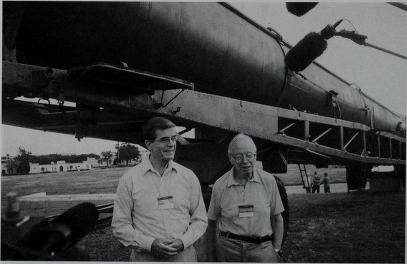

Hawkins (left) and Esterline together in Washington in 1996 reviewing declassified documents during their first meeting since the ill-fated Bay of Pigs invasion. Author’s Collection

Richard Bissell (right) with Sen. Frank Church during the 1975 Church Committee hearings about assassination plots against foreign leaders. Bissell, as the CIA’s deputy director for plans, controlled CIA operations against Cuba through the Bay of Pigs disaster. Bissell ignored Hawkins and Esterline’s warning that the changes to the invasion plans would likely lead to failure. Miami Herald

President Kennedy’s aides Theodore Sorensen (left) and Arthur Schlesinger Jr. recall the October 1962 Cuban Missile Crisis at a missile display in Havana. They were in Cuba at a conference marking the fortieth anniversary of the missile crisis. Author’s Collection

Sam Halpern started with the CIA’s Cuban operation in the fall of 1961. He was executive assistant to Bill Harvey, who headed the CIA’s Task Forte W for Operation Mongoose and, subsequently, to Desmond FitzGerald, who headed the CIA’s Special Affairs Staff, responsible for postMongoose covert operations against Cuba. The date of the picture unknown. Sam Halpern

* *

SIT v