SOUTH CAIilPus

_ $fk "f 1 &.DePT AoilCULTiJit

US.A.BMV COMUONiCATONS 5 • SERVICE CROUP •• BUILDING HO. 3

■ US. ARM ELEMENT CCUWSIE

*, OPERATIONS 0«W 8T38

, VfHSE. NO_2

...nrnil' 'tj&l4TH WUIM SUDXtSiEtr

Building #25 on the University of Miami’s secluded, 1,572-acre South Campus, served as the CIA’s JMWAVE station from late 1961 until 1968. This photograph was taken in 1964. For a time, this command center for U.S. operations against Cuba was the largest CIA station in the world outside of the Langley, Virginia, headquarters. The station operated under the cover name of Zenith Technical Enterprises, Inc. Miami Herald

CUADERNOS 01 TEMAS POLITICOS 4

sfw r^m^ x ^>r~~ -* v i S' IF H " x " ifs. y ^

Jllage of anti-Castro propaganda material published by several CIA-subsidized exile anizations after the Bay of Pigs. Author’s Cnii^ti™

Left to right, Erneido Oliva, Jose “Pepe” San Roman, and Manuel “Manolo” Artime, all leaders of the Bay of Pigs invasion brigade, display their joy shortly after returning to Miami in December 1962 after spending twenty months as Cuban prisoners. Miami Herald

President Kennedy is presented with Brigade 2506 colors on December 29, 1962, in the Miami Orange Bowl. This was part of the welcome-home ceremony for 1,113 Bay of Pigs prisoners who were ransomed for $54 million in food and medicine. At the ceremony, Kennedy promised to return the flag to the brigade in a “free Havana.” The flag is presented to Kennedy by Oliva (right), the brigade’s second in command. Artime, the Cuban Revolutionary Council’s representative to the brigade, is in the center. Miami Herald

Cuban Revolutionary Council member Anthony “Tony” Varona was involved in both CIA-Mafia plots to assassinate Castro. Miami Herald

Rolando Cubela, code-named AMLASH, was a fighter in the war against Batista and, after Batista’s fall, a member of Fidel Castro’s inner coterie. After becoming disillusioned with Castro’s revolution, he became a CIA “asset” from 1961 to 1965. Cubela wanted to assassinate Castro, and the CIA supplied him with assassination tools. But the plans never panned out, and he was arrested in Cuba in 1966. This picture is believed to have been taken before 1959 when he was a leader of the Revolutionary Student Directorate fighting Batista. Miami Herald

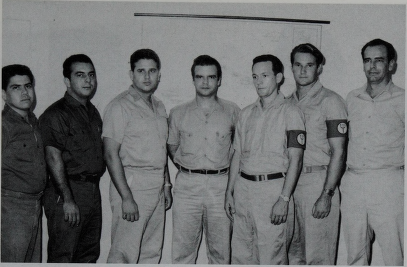

Pictured are seven leaders of Artime’s U.S.-supported “autonomous group” that operated against Cuba from bases in Nicaragua and Costa Rica in 1964 and 1965. The paramilitary group’s decline began in September 1964 when they mistakenly attacked a Spanish freighter headed for Havana, killing several crew members. Artime is in the center of the picture. His deputy, Rafael Quintero, is second from the left. The others are unknown. Rafael Quintero

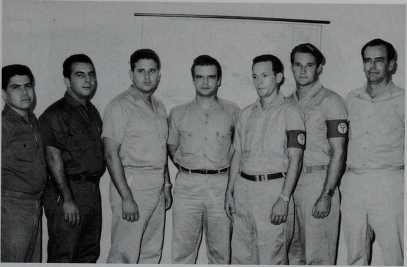

Quintero, far right, and Artime, second from right, point out targets in Cuba to unidentified members of the group at one of their Central American camps. Rafael Quintero

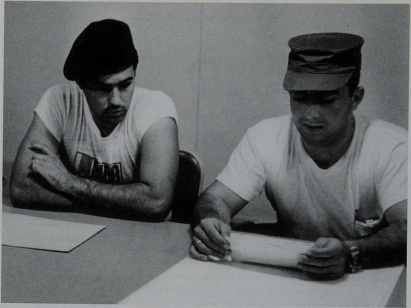

Quintero (right) and Segundo Borges, chief of the infiltration teams for Artime’s Central American operation, discuss strategy at one of the group s Costa Rican camps in 1964. Rafael Quintero

The shoulder-patch emblem of the CIA-run Cuban-exile group Commandos Mambises. Sam Halpern

5

The CIA recruited Carlos Obregon, currently a Miami businessman and a onetime member of the Revolutionary Student Directorate, in 1961. He became an infiltration team leader, and this photograph was taken circa 1966 in Cuba’s Las Villas Province. Carlos Obregon

Oliva (right), second in command of the Bay of Pigs invasion brigade, and Rafael del Pmo, who was a Castro pilot at the Bay of Pigs fighting against the brigade, embrace in 1989 after del Pino’s defection. Erneido Oliva

component of Mongoose. Harvey met Rosselli in Miami, telling him to maintain his Cuban contacts but not to deal with Maheu or Giancana. The poison pill scheme was reactivated, with Varona again enlisted, through Rosselli, as the deliveryman. Harvey gave the pills to Rosselli in Miami on April 21, 1962. Rosselli told the Church Committee that he told Harvey that the “Cubans” (Varona) planned to use the pills on Fidel and Raul Castro and Che Guevara, and that Harvey had approved.

Varona wanted arms and equipment as a quid pro quo for doing the job. Harvey enlisted the Miami Station to help, although Shackley said he was not aware he was part of an assassination plot. “Harvey was, in his way, highly professional,” said Shackley. “He kept things compartmentalized and I wasn’t part of the operation.” 42 Harvey and Shackley rented a U-Haul truck under an assumed name, loaded it with explosives, detonators, rifles, handguns, radios, and boat radar valued at some $5,000, and delivered it to a Miami parking lot. The truck keys were given to Rosselli, who watched the delivery with O’Connell, from across the street. The truckload was finally picked up. Nothing happened. In May Rosselli told Harvey the pills had been delivered to Cuba. Nothing happened. In September Rosselli told Harvey that Varona was preparing to send in another three-man team to “penetrate Castro’s bodyguard” and that the pills, referred to as “the medicine,” were still “safe” in Cuba. Still nothing happened. Harvey ended the operation in mid-February 1963. 43

Even as the second phase got under way in April 1962, the residue of an incident in the first phase came back to haunt the operation and caused Bobby Kennedy to become aware of the assassination plot. In October 1961 Giancana was in Miami and wanted Maheu to arrange for a bug of the Las Vegas hotel room in which his girlfriend, Phyllis McGuire of the singing McGuire Sisters, was staying. Giancana believed she was cheating on him with Dan Rowan of the Rowan and Martin comedy team. A maid walked into the room while the bug was being installed, and the local sheriff’s office was called. Maheu fixed the matter with local authorities, but word had already reached the FBI, which decided to seek prosecution under wiretapping statutes. But word eventually reached the attorney general, Bobby Kennedy. Lawrence Houston, the CIA’s general counsel, and Sheffield Edwards, the security director, briefed Kennedy on May 7, 1962. Edwards said Kennedy was briefed “all the way.” Houston said that after the briefing, Kennedy “thought about the problem quite seriously.” The attorney general said that he could not proceed against those involved in the wiretapping case. “He spoke quite firmly, saying in

effect, ‘I trust that if you ever try to do business with organized crime again—with gangsters—you will let the Attorney General know before you do it.” Houston quoted Edwards as replying that this was a reasonable request, but Kennedy was not told the plot had been reactivated. 44 At Kennedy’s request Edwards wrote a memorandum for the record of the incident a week later. 45

Some months after the McGuire bugging incident, the FBI discovered that Giancana’s girlfriend, Judith Campbell Exner, had been calling President Kennedy from Giancana’s home phone. President Kennedy and Giancana were sharing the same girlfriend in bed, and each knew it. President Kennedy was made aware of the FBI discovery and ended his relationship with Exner. But the incident prompted renewed FBI interest in the McGuire bugging episode. FBI Director J. Edgar Hoover wanted a full explanation from the CIA as to why it resisted prosecution, which led to the Houston and Edwards briefing of Bobby Kennedy. 46 Exner, who died in 1999, gained minor celebrity status with tell-all tales of her eighteenmonth affair with President Kennedy, but her credibility suffered from the conflicting accounts she offered. Giancana was murdered in the basement kitchen of his Illinois home on June 19, 1975. Rosselli disappeared from his South Florida home July 17, 1976. Fishermen found his body eleven days later, stuffed in a drum in a Miami area bay.

Two other assassination plots surfaced in early 1963, both of which fell in the “nutty schemes” category. The first involved James Donovan, although he did not know it. The idea was to have Donovan present Castro with a skin-diving suit dusted “with a fungus that would produce a disabling and chronic skin disease” and “a breathing apparatus contaminated with tubercle baccili.” Dr. Sidney Gottlieb, a CIA scientific adviser, said that the plan had progressed to the point of actually buying a diving suit and readying it for delivery, but he didn’t know what happened to the plan or the suit. Sam Halpern, who also was privy to the plot, first said it was dropped because it was impracticable and later recalled that Donovan had already given Castro a skin-diving suit on his own initiative. There was conflicting testimony as to whether the plan was initiated by Harvey or FitzGerald. 47 Ted Shackley, like many CIA personnel, believed the Kennedys were aware of the various assassination plots. As an indication of their knowledge, Shackley cited conversations he had with Donovan “who had been talking with the Kennedys, and Bobby

ACCOMMODATION OR ASSASSINATION

wanted to know what Castro did, details about skin-diving and other things.”

A second plot, even more mind-boggling, which originated with FitzGerald, would have had Castro assassinated by an exploding seashell. “The idea,” according to the IG’s report, “was to take an unusually spectacular sea shell that would be certain to catch Castro’s eye, load it with an explosive triggered to blow when the shell was lifted, and submerge it in an area where Castro often went skin diving.” FitzGerald went so far as to purchase two books on Caribbean mollusca. But the idea was given up as impracticable when it was found that “none of the shells that might conceivably be found in the Caribbean area was both spectacular enough to be sure of attracting attention and large enough to hold the needed volume of explosive.” In addition, the midget submarine they would have had to use to plant the shell had too short an operating range for the operation. 48

Sam Halpern was another among the many CIA officers who firmly believed the Kennedys were aware of the Castro assassination plots. Halpern said he never talked to his bosses about it but “I believe my bosses were honest people, like Des FitzGerald. ... It was from Des that I got very clearly time and time again, that’s what these guys wanted,” meaning Castro’s assassination and the Kennedys. Halpern cited a Monday morning when FitzGerald walked into the office with a coffee table book on Caribbean seashells and asked Halpern to have the technicians blow up a picture of one of the shells. Halpern asked, “Are you kidding or something? What’s going on?” FitzGerald responded, “You don’t know the pressure I’m under . . . that kind of stuff.” FitzGerald, who was socially connected with the Kennedy crowd, “wouldn’t do those things on his own. He wasn’t a cowboy. He was a damn well-disciplined officer and knew what the hell was going on.” 49

Halpern also recounted for the Church Committee the time in October of 1961, shortly after he became involved in Cuba and Richard Bissell was his boss. “Mr. Bissell said he had recently—and he didn’t specify the date or the time—he had recently been chewed out in the Cabinet Room of the White House by both the President and the Attorney General for, as he put it, sitting on his ass and not doing anything about getting rid of Castro and the Castro regime. His orders to both [name blacked out] and to me were to plan for an operation to accomplish that end. . . . There was no limitation of any kind. Nothing was forbidden, and nothing was withheld. And the objective was to remove Castro and his regime.” 50

Halpern said later that “when I asked Dick Bissell about what does ‘get rid of,’ mean, he said ‘you can read the English language as well as I can. Get rid of, means get rid of,’ so that’s why I went along with the AMLASH operation which was in ’63.” 51

Tom Parrott was another who said he did not believe “for one second” the oft-repeated contention by Arthur Schlesinger that the Kennedys did not know of the assassination attempts against Castro.

“I’m convinced that Bobby knew plenty about it and was the engine behind it to a considerable extent. Not necessarily directly, by saying you go out and assassinate Castro but saying, you know, ‘Why don’t you get off your duff and do something? We don’t care what you do.’ He knew perfectly well, I m convinced. Now, I don’t suppose you’re going to find any piece of paper where he obviously says that. How much the president knew, I just don’t really know. But somehow I have the feeling that he knew more than he was admitting or more than his sycophants were admitting.” 52

No conclusive evidence has been found to show that either President Kennedy or his brother, Bobby, the attorney general, had prior knowledge of the assassination plots. The same applies for Presidents Eisenhower and Johnson, whose administrations were also encompassed in the Church Committee report. The committee concluded, however, that it found “the system of executive command and control was so ambiguous that it is difficult to be certain at what levels assassination activity was known and authorized. This situation creates the disturbing prospect that Government officials might have undertaken the assassination plots without it having been uncontrovertibly clear that there was explicit authorization from the Presidents. It is also possible that there might have been a successful plausible denial in which Presidential authorization was issued but is now obscured. Whether or not the respective Presidents knew of or authorized the plots, as chief executive officer of the United States, each must bear the ultimate responsibility for the activities of his subordinates.” 53

CHAPTER

A mong the least known, least understood, most creative, and most controversial of the many covert U.S. activities targeting Cuba involved “giving the Cubans their heads,” as Assistant Secretary of State Ed Martin phrased it. Martin’s October 1962 proposal built on the two-track policy “to engage Cubans more deeply ... in efforts of their own liberation” suggested a month earlier by Walt Rostow, chairman of the State Department’s Policy Planning Council. Shortly after Martin’s proposal, the missile crisis exploded and the idea was put on ice, to be resurrected and ultimately approved in June 1963 as the cornerstone of the new post-Mongoose covert policy targeting Cuba.

As Martin envisioned it, the autonomous program would provide the “selected exile group with funds, arms, sabotage equipment, transport, and communications equipment for infiltration operations in order to build a political base of opposition within. We would provide the best technical advice we could. Our role would essentially be that of advisors and purveyors of material goods—it would be the exile group’s show. We would insist that hit and run raids or similar harassing activities that clearly originate from outside Cuba and do not reflect internal activity [within Cuba] not be engaged in.” 1

Sam Halpern described the program more succinctly: “The next thing we knew, the word was ‘let Cubans be Cubans.’ Let the Cubans do their own thing. But the Cubans didn’t have any money. So, the CIA’s got money. Give ’em money. We gave them money. We told ’em where to buy arms, ammunition. We didn’t give it to ’em. They went out and bought their own. They decided what they wanted. They picked their own targets, then they told us what their targets were. We provided them intelligence support. . . . We didn’t have anything to do with what they were up to. They just told us what they were going to do and we said, ‘Fine. We’re not stopping you.’ And we didn’t.” 2

As with virtually every other covert activity aimed at Cuba in the post

Bay of Pigs period, Bobby Kennedy was the new program’s eager engineer. The CIA, at least at the operational level, was the reluctant conductor. The only two groups ultimately to benefit from “giving the Cubans their heads” were the (MRR), led by Manuel Artime, and the Cuban Revolutionary Junta (JURE) headed by Manuel Ray. They were referred to in official documents as the “autonomous groups.” Declassified documents indicate that a third exile group, Comandos L, was considered for funding but never approved. (It has been reported, apparently erroneously, that the Artime organization operated under the code name of Second Naval Guerrilla. Neither the CIA’s Halpern nor Artime’s deputy, Rafael “Chi Chi” Quintero, had ever heard this code name. Nor was such a reference found in any of the many declassified documents now available. 3 )

Artime had been the political representative of the Cuban Revolutionary Council, the exile group organized and subsidized by the CIA to front for the Bay of Pigs Brigade. He landed with the invaders and was among those captured and imprisoned in Cuba until December 1962. He was known as the CIA’s “Golden Boy,” but as far as the so-called autonomous operations were concerned, Artime was Bobby Kennedy’s “Golden Boy.” Manuel Ray, public works minister early in Castro’s government before defecting, was thought to have a large underground following within Cuba. He had become a favorite of many in the Kennedy administration, particularly White House aide Arthur Schlesinger Jr. Under White House pressure Ray was belatedly added to the Cuban Revolutionary Council on the eve of the Bay of Pigs invasion, but was not part of the invasion force. He was regarded as too liberal by many conservative exiles, and some within the CIA, who saw him as an advocate of Fidelismo sin Fidel or Fidelism without Fidel.

Martin recommended that the autonomous program begin only with Ray’s JURE, noting the “problems would multiply” if more groups were involved. “In sum,” warned Martin, “we should be cautious about grandiose schemes, a ‘major’ U.S. effort, and deep commitments to the exiles. We should experiment in this new venture on a small scale with patience and tolerance for high noise levels and mistakes.” It was a prescient warning.

Approved by the president on June 19, 1963, as part of the CIA’s broader Integrated Covert Action Program for Cuba, the “rules of engagement” for the autonomous operations were:

(1) It is the keystone of autonomous operations that they will be executed exclusively by Cuban nationals motivated by the conviction that the overthrow of the Castro/Communist regime must be accomplished by Cubans, both inside and outside Cuba acting in consonance.

(2) The effort will probably cost many Cuban lives. If this cost in lives becomes unacceptable to the U.S. conscience, autonomous operations can be effectively halted by the withdrawal of U.S. support; but once halted, it cannot be resumed.

(3) All autonomous operations will be mounted outside the territory of the United States.

(4) The United States Government must be prepared to deny publicly any participation in these acts no matter how loud or even how accurate may be the reports of U.S. complicity.

(5) The United States presence and direct participation in the operation would be kept to an absolute minimum. Before entering into an operational relationship with a group, the U.S. representative will make it clear that his Government has no intention of intervening militarily except to counter intervention by the Soviets. An experienced CIA officer would be assigned to work with the group in a liaison capacity. He would provide general advice as requested as well as funds and necessary material support.

He may be expected to influence but not control the conduct of operations.

(6) These operations would not be undertaken within a fixed time schedule. 4

Bobby Kennedy wasn’t waiting for the president’s formal approval to get the autonomous program on track. In early December 1962, even before the missile crisis dust had settled, he called Quintero for a visit to Hickory Hill, the Kennedy estate in McLean, Virginia. “He had a plan in mind,” Quintero said. “He wanted a separate operation. My feeling was that this man was a man working behind the scenes, who wanted personal knowledge, not just what he was told by a government agency. He was very knowledgeable. He could talk about people and places on the map.” He asked Quintero who could unite the Cuban opposition. Quintero, a longtime Artime friend and collaborator, suggested Artime was the man. 5

The Bay of Pigs prisoners were released later the same month, among them Artime and Erneido Oliva, the brigade’s second in command. Oliva had served in both Batista’s army and Castro’s army before being spirited out of Cuba in August 1960 to join the brigade training camps in Guatemala. During the battle at the Bay of Pigs he had distinguished himself in

defeat. As Oliva walked from the plane after arriving in Homestead, Florida, from Cuba, Enrique Ruiz Williams, a wounded prisoner released earlier, called: “ ‘Erneido, come, I have somebody who wants to say hello to you.’ There was a portable telephone, and when I took it, it was Bobby Kennedy,” said Oliva. “He welcomed me to the United States and, in my broken English, I said I was looking forward to meeting him.”

Two days later, Oliva, Artime, and other brigade leaders were in Washington meeting with administration officials to prepare for the official December 29 welcoming ceremony for the returned prisoners in Miami’s Orange Bowl. Bobby Kennedy was among those they met. The brigade leaders continued their treks back and forth between Miami and Washington after the ceremony, conferring with Pentagon and CIA officials about Cuba. During a mid-January visit to Washington, Oliva and Artime were invited by Bobby Kennedy to Hickory Hill, where the trio discussed the end of Mongoose and potential new anti-Castro efforts. Bobby told them of the Kennedy administration’s plan to incorporate brigade members into the U.S. military for training and revealed the basic outline for what was to become Artime’s $6- to $7-million effort in Central America. “Artime would be in charge of the paramilitary operation from a country in Central America, not identified at that time, and Oliva in charge of the conventional force,” said Oliva. “What Artime was doing, what Oliva was doing, the projects were supposed to mesh. . . . The plans were that at a given time, when Artime’s operation gets stronger against Castro, and along with the people inside Cuba, then my officers will get together with the enlisted personnel at Ft. Jackson and organize a unit.”

Shortly after the Hickory Hill meeting, Artime and Quintero started laying the groundwork and lobbying Central American officials for the new anti-Castro operation. Oliva and 207 other brigade members were sworn in March 11, 1963, as commissioned officers in the U.S. Army and assigned to Fort Benning, Georgia, for training. President Kennedy formally designated Oliva as the representative for Cuban-Americans in the U.S. military. In addition to the Fort Benning officer group, they included several thousand Cuban enlisted men—many of whom had been recruited during the missile crisis—stationed at Fort Jackson, South Carolina. As their representative, Oliva’s liaison at the Pentagon was Alexander Haig Jr.

To accentuate the link between them, Artime visited Oliva at Fort Benning in the spring of 1963 to recruit some of the Cuban officers there for his Central American operation. Oliva said he told Artime, “You can take

them if they want to go.” Among those at Fort Benning who resigned their commissions and signed on with Artime were Felix Rodriguez and Gustavo Villoldo, both later to gain notoriety as the CIA agents who helped the Bolivian military track down Che Guevara in October 1967. Artime invited Oliva to become the Central American operation’s military commander. Oliva declined, preferring to remain in the U.S. Army. 6

The first clear indication of approval for agency involvement with the autonomous groups came in a CIA paper dated May 16, 1963, although formal presidential approval didn’t come for another month. The paper on sabotage in Cuba noted “approval has been granted for Agency support to selected exile groups which are largely autonomous. The first, and most promising, of these is represented by Artime. His planned survey trip to Central America was delayed because of a feeling that he might represent a possible asset in connection with Haiti.” However, Artime was now ready to go to Central America, and “at the conclusion of his survey, in about a month, the Agency will bring an over-all plan of operation for approval by the Special Group.” 7

The task of finding a location in Central America where the Artime group could operate fell mainly to Rafael Quintero. Among the most dedicated and tenacious in the anti-Castro fight, Quintero had been with Artime’s MRR in the Sierra Maestra against Batista. He fled Cuba for Miami in November 1959. In December he went to Mexico to join Artime after Artime’s defection. Returning to Miami in March 1960, Quintero was number twenty-seven to sign up for the Bay of Pigs. His first stop for that operation was Useppa Island, off Florida’s gulf coast, for radio communications training. Next he moved to the Guatemala training camps. Returning to Miami in November, he spent a month delivering supplies to the resistance in Cuba before his own infiltration into the island to work with the underground in the period before and after the Bay of Pigs. He returned to Miami in September 1961. Three months later he was back in Cuba, coming out for the final time in April 1962. Then, at Bobby Kennedy’s behest, he went to Latin America to enlist support for the release of the Bay of Pigs prisoners. After his return from Latin America, he began working for the agency again in Miami, ferrying weapons into and people in and out of Cuba, until Artime’s release from prison.

Quintero’s search for a camp location first focused on Nicaragua. In early 1963 he spent “like three months going to Nicaragua every week

looking for a site for the camps. . . . We spent a long time picking out a site ... a convenient site that Luis Somoza [Nicaraguan president] had to approve. We picked out two or three places that they rejected. At the same time, Artime started lobbying people in Costa Rica . . . President [Francisco] Orlich. And that was easy, because he decided that his brother’s farm was going to be the place that we could build a camp.” Meanwhile, the people in Washington “were getting a little bit disturbed because we were taking a little bit too much time doing this.”

It wasn’t easy. “On the Atlantic Coast of Nicaragua there was nothing,” said Quintero. “We didn’t have any type of communication ... only boats or planes. They didn’t have any roads at that time. It was hard to get everybody together in Nicaragua to say, ‘well, we’re going to fly over this area tomorrow.’ You needed to get the plane. You needed to get the pilot. And the weather in Nicaragua is very rough for a small airplane. At 12 o’clock everything is closed. You cannot fly because the clouds are too low and the Nicaraguan pilots were not that good. Anyway, it took some time to finally say this is the place where we are going to go.”

The “place” for one site was Monkey Point, at the tip of a peninsula near El Bluff. “We go see the head of the province and he said ‘I’ve got another place you can use.’ ” It was up the coast near Puerto Cabezas, from where the Bay of Pigs invaders set sail. Things were much easier there. “The commander of the area was very good, very helpful, and we didn’t have any problems.” Monkey Point was a swamp, Quintero recalled, “so we have to build all that. It took us a lot of time and equipment. We had to build the camp. We have to build a dock. We have to prepare an airfield. It was totally swamp when we went there. It was very well located, but Somoza didn’t want us close to any area where people were living.”

By late 1963 the camps were up and running. In Nicaragua the maritime operation was at Monkey Point. The commandos—numbering about ninety people—were at Puerto Cabezas. In Costa Rica the infiltration teams were at the Orlich farm in Sarapiqui. A radio operators’ base and a weapons barge were at Tortuguero. “So we are talking now about five bases plus one other camp because we had the communications center in San Jose. So we had six places that we had to look out for, secure, and get people for,” said Quintero. There also was a refueling base in the Dominican Republic. The total number of exiles in the Central American camps eventually reached about three hundred.

Although they had a common border, Costa Rica and Nicaragua were

not on the friendliest of terms. As a result, an effort was made to keep the Nicaraguan and Costa Rican operations as separate as possible. Neither country was told what was going on within its neighbor’s borders. “We have more camps and more sophisticated equipment in Costa Rica, but we have more people in Nicaragua,” said Quintero. “The Monkey Point base was a big base with a lot of people. ... We have a couple of airplanes there and the boats, two operational boats, and we have a couple of mother ships.” 8

There are indications Washington provided some assistance for both Artime and Ray to find operational locations. One declassified document carried only the heading, “Talking Points to be Used in Conversation with Foreign Minister Oduber Concerning Cuban Exile Activity,” which was prepared to lobby Costa Rican foreign minister Daniel Oduber on behalf of both the anointed exile leaders. The document begins, the United States considers both men “responsible and dedicated Cuban patriots” who “approach the problem of freeing their country somewhat differently: Artime looks to the eventual mounting of guerrilla and sabotage operations inside Cuba while Ray’s emphasis is on the employment of politico-psychological means within Cuba to encourage defections in the Communist regime and thus to erode the power structure.” More significantly, it read the “provision of assistance to these two men is, of course, a matter for the Costa Rican Government itself to decide. For our part, however, we would not discourage such support or assistance.” It noted that the U.S. government “does not control Artime or Ray,” and added, somewhat ingenuously: “Our information is that they obtain assistance from democratic Latin American individuals and organizations who wish to see the establishment of democracy in Cuba.” 9

A declassified chronology of the autonomous operations based on policy discussions at Special Group meetings, showed that by July 9, 1963, Manuel Ray’s JURE was getting a monthly subsidy of $10,000. Payment to Artime’s MRR was not noted but the chronology did report that his operation had “moved forward rapidly in the past three weeks,” with Nicaragua “supplying a base, cover, and logistical support for the operation. In addition, a description was given of the Costa Rican political base worked out by ARTIME.” 10

The chronology entry for July 16, 1963, a week later, reported “the question of disappointingly premature publicity concerning our autonomous operations with ARTIME was raised. The discussion centered on

means of counteracting this premature publicity and several suggestions to do so were made. There was no suggestion of changing the autonomous operation concept.” The CIA’s Desmond FitzGerald reported on the problem at a meeting of the National Security Council’s Standing Group. A summary record of the meeting reads: “There was a discussion of the widespread press reports that the U.S. was backing Cuban exiles who are planning raids against Cuba from Central American States. One news article shown the Attorney General was headed ‘Backstage with Bobby’ and referred to his [Bobby Kennedy] conversations with persons involved in planning the Cuban raids.” The article, written by Hal Hendrix, appeared in the Miami News on July 14, 1963. 11

Another story by Hendrix appeared two days later under the heading: “Top Exile Fighter Quits U.S. for Base.” It was an interview with Artime in which he said he was leaving the United States to direct an anti-Castro guerrilla army from a headquarters somewhere in Central America. The story said, “Artime denied vigorously reports circulating here and in Washington that he is being supported and financed by Attorney General Robert Kennedy. ‘I have no association with the attorney general,’ Artime asserted.” Artime added that his support was coming from “some Latin governments, some wealthy Latin Americans and some Latin Political parties” who have helped provide financing and weapons. 12

The first story by Hendrix, headed “Backstage with Bobby,” could have quite possibly come from CIA sources, perhaps even Ted Shackley in Miami, with whom Hendrix was well acquainted. The CIA—especially its operational personnel such as Shackley—was not enthusiastic about the autonomous operations. “The whole operation was set up as a result of Artime’s discussion with the Kennedys,” Shackley said in an interview. “I was asked my opinion on it and I said it was a lousy idea. They had basically been out of Cuba too long and were not aware of the operational realities in Cuba,” which had grown considerably more difficult by 1963. In addition, said Shackley, “Artime didn’t have the managerial skills to run this. It was not cost effective to provide them with the support mechanism they would need for being successful.” The JMWAVE station in Miami had given Artime a two-week “tutorial” to try and make him “a competent manager of a large clandestine program,” said Shackley. “It was clear at the end of it that it was not going to work. After that, our role in Miami was support when Artime was in Miami. I would meet him, but it was an RFK operation,” one which Shackley described as “an exercise in futility.” 13

Shackley had even less regard for the other autonomous operation headed by Manuel Ray. “Ray captured attention . . . because he was further to the left and sold the Kennedys. His [CIA] case officer was A1 Rodriguez and I told him the thing was a poor effort, a waste of time. The [JMWAVE] station had nothing to do with Ray. He never did anything.” 14 Disdain for the autonomous groups within the bureaucracy wasn’t limited to the CIA. John Crimmins, by then the coordinator for Cuban affairs, said he was “strongly opposed to them. I never forgave Des [FitzGerald] for pushing for the autonomous business. For someone who didn’t like the thing, he was very convincing about the virtues of the autonomous approach.” 15

It was obvious, said Quintero, that the CIA was a reluctant supporter of the autonomous groups. “I remember the first meeting Artime and I had with the CIA guys, when we start planning for Central America. The guy told him, ‘This is not as if we chose a name out of a hat for you to be in charge of this operation. It has gone very high and you were picked out to be the guy who is going to run this operation.’ That guy [who made the decision] was Bobby Kennedy, who we had met and who was interested in doing something when almost everything else was dead here.” 16 And with Bobby Kennedy in charge, it would take more than bureaucratic unhappiness to halt the program.

At the same time, word of Artime’s operation was getting around. CIA Director John McCone, in a July 20 memo, advised the attorney general that according to an agency representative in Miami, Jose “Pepin” Bosch, the Cuban-born Bacardi rum boss, had met with Luis Somoza, who “told him of U.S. support for anti-Castro operations from Nicaragua. Bosch said that during a meeting with Somoza on 15 July Somoza indicated that he had received a green light from the Attorney General Robert F. Kennedy to mount anti-Castro raider and resistance operations from Nicaraguan bases. Somoza said that the Attorney General wanted him to work with Manuel Artime, Erneido Oliva and the brothers Jose and Roberto PEREZ-San Roman in implementing anti-Castro operations. Somoza told Bosch that he would use these men but wanted to maintain flexibility, which would also allow him to work with other promising Cuban exiles. Somoza said the Attorney General agreed that he should have full flexibility to handle the matter as he saw fit.” 17

Somoza may have had an ulterior motive, as can be seen from the August 8 entry in the CIA chronology of the autonomous groups, which reads in part: “A status report on ARTIME’s operation was discussed,

THE CASTRO OBSESSION

particularly Luis SOMOZA’s efforts to push planned harassment operations in the hope that Castro might launch an offensive against Nicaragua which SOMOZA believed would bring forth U.S. intervention.” Somoza’s efforts encouraged Artime to shift the bulk of his operations to Costa Rica “without breaking with Somoza.” 18 Luis Somoza was by then no longer president, but he still exercised political power directly, or through Rene Schick, his handpicked successor.

!M!eanwhile, Ray continued to operate from South Florida and Puerto Rico despite the mandate that autonomous group activities were supposed to be “mounted outside the territory of the United States.” Declassified documents indicated Ray tried unsuccessfully to get a campsite in Costa Rica, but finally did get a small base in the Dominican Republic. Eloy Gutierrez Menoyo, another veteran of the war against Batista, who defected in January 1961, also had a base in the Dominican Republic, grouping three organizations: his own Second National Front of the Escambray, Alpha 66, which he had helped organize earlier in Miami, and remnants of Ray’s old Peoples Revolutionary Movement (MRP). Menoyo did not receive funding under the autonomous program benefiting Ray and Artime, although he was held in higher esteem by U.S. officials than were many other militant exile leaders. Declassified documents hint that he might have received limited support from the Defense Department. For example, a memo for the record of the January 9, 1964, Special Group meeting showed that the Department of the Army requested and received approval for two “clandestine intelligence operations.” One was for “the establishment of a clandestine net using the Second National Front of the Escambray.” 19 After dropping from sight in mid-1964, Menoyo led a four-man band that infiltrated Cuba from the Dominican Republic in late December 1964. Others of his organization were apparently to follow, but Menoyo and his three companions were captured in late January 1965 near Baracoa in eastern Cuba. A filmed interrogation of the four was presented on Cuban television February 3, 1965, in which Menoyo “confessed” that he had worked earlier with the CIA in sabotage operations after being trained by the agency to “handle explosives, read maps and assemble some weapons with which I was not familiar, such as the 30caliber machinegun.” 20

By November “Artime and the MRR has [sic] made substantial progress and expects to mount his first operations in December,” according to the

CIA chronology entry, based on a White House meeting to review the Cuban program. Ray was now receiving $25,000 of support monthly, “although he has not progressed to the point that ARTIME has. Higher Authority [the president] concurred that the program continue.” Concern about control reemerged, as McCone “emphasized that to a very considerable extent they [the autonomous groups] were uncontrollable and forecast that once ARTIME was in business we might expect some events to take place which were not exactly to our liking.” 21 McCone was proven right in dramatic fashion ten months later when Artime’s group mistakenly fired on a Spanish freighter off the Cuban coast, killing several crewmen and igniting a major diplomatic flap.

But in late 1963, the problem was more mundane: getting the program operational. “It’s difficult to say when we finally became operational, because we had so many problems,” said Quintero. “We had logistical problems. We had political problems with the camps. It was very difficult trying to deal with the government of Costa Rica and them not knowing what we were doing in Nicaragua, and the Nicaraguan government not knowing what we were doing in Costa Rica. I would say it was early 1964 before we had a base you could get the infiltration teams, the commandos and all the maritime operations running.... You could get people in and out [of Cuba] from a maritime point of view.” Another problem, said Quintero, was CIA reluctance. “The CIA wasn’t really very happy with the operation. It was something Bobby Kennedy made them do so they had to support us, but they didn’t do it willingly. It was another battle that you had to fight.”

For Artime and Quintero, there were also the regular monthly meetings with their CIA case officer, Henry Heckscher. Heckscher had been involved with the Bay of Pigs, and Quintero had first met him on Useppa Island and later saw him in the Guatemala training camps. He was later the CIA station chief in Chile at the beginning of Salvador Allende’s presidency in 1970. “Henry was reluctant to work with us because somebody dropped it in his lap, and he didn’t want it,” said Quintero. “But he was a very professional man, and he felt we were wasting our time with what we were doing; that it would only work if we could have some professional advice. He talked to Artime very much about trying to get a brain trust behind him that would tell him what to do, how to do it and when to do it.”

The meetings, said Quintero, usually lasted two days and were held in various U.S. cities, among them San Francisco, Atlanta, San Juan, and

Washington, but never Miami. “First we explained the budget for that month; second all the plans we have. We made all the recommendations and what we thought about them. We gave a report of how training was going and explained what plans we have for the coming month. And we had a lot of logistical problems, as you can imagine. To build a camp in the middle of nowhere in the jungle is not an easy task. Then there were all the political problems. That took almost 90 percent of Artime’s time, trying to keep Orlich and Somoza satisfied. You know how all these people . . . you know how all the governments are. They want money.” In Costa Rica, the Artime group shared an airstrip on the farm with Orlich’s brother. “We were using it for our program and he was using it for his own program,” said Quintero. And “his program” apparently involved smuggling whiskey and other contraband. “One of the guys we were dealing with in Nicaragua was Ivan Alegrett, who was the consul in Miami. He was kicked out as consul for drug problems, and when he got to Managua, Somoza named him the head of immigration, so you can imagine.” 22

Eventually, things began falling into place. Tito Mesa, a Cuban exile friend of Artime’s, had set up a front company, Maritima Bam, S.A., in Panama for the operation’s business transactions. (The BAM represented Artime’s initials in reverse, Manuel Artime Buesa.) CIA funding was channeled from Switzerland to the Coconut Grove Bank in Miami under the name of Walter Oppenheimer, who was actually Artime. 23 November brought the big enchilada in the form of a barge loaded with 110 tons of arms, ammunition, explosives, and other military equipment. The Defense Department carried out this operation with the approval of the Special Group, “in a manner designed to preclude attributability to the United States, and to attribute the origin of the arms and their means of delivery to European commercial firms.” Even the Artime group thought the arms were purchased and transferred from Germany. The operation involved a complex plan under which the CIA obtained a barge, which was picked up in Baltimore by a Navy tug, then towed to the Naval Ammunition Depot in Yorktown, Virginia, where the CIA delivered the arms shipment for loading. The barge was then towed to an area near the Naval Amphibious Base at Little Creek, Virginia, where it was picked up by another vessel that towed it during darkness to a designated spot in international waters off Costa Rica’s Atlantic Coast. The tow vessel departed as the CIA maintained surveillance of the anchored barge from a smaller boat nearby until it was retrieved by Artime’s men and towed up the jungled Tortu

guero River where it was anchored. 24 There the stationary barge, guarded by a seventeen-member security team, became the arms and ammunition storage facility during the course of the Artime operation. When a weapon was needed, said Quintero, it was picked up from the barge.

Only a month or so before that, Erneido Oliva, now at Fort Still, Oklahoma, had been given the go-ahead, after heavy lobbying of Bobby Kennedy and Oliva’s Pentagon contacts, to draft a plan to incorporate all the Cubans in the U.S. Army into a single unit. “Remember, I was a pushy guy. I kept calling and said, ‘Hey, what are we going to do?’ until October, I think, when they called me and said, hey, ‘prepare something.’ ” Oliva is convinced that had President Kennedy lived, the Cuban unit was a force that would eventually have been used against Cuba in conjunction with Artime’s operation, despite Kennedy’s no-invasion pledge.

Oliva thinks it quite possible that Artime would have provoked a confrontation that would have drawn a reaction from Castro and, in turn, brought a U.S. response. 25 This idea might not be so far-fetched, given that Luis Somoza appeared to be thinking along the same lines. In fact, Castro said in October 2002, at a fortieth anniversary missile crisis conference in Havana, that one of the reasons he had been so resistant to the withdrawal of the Soviet IL-28 bombers from Cuba was the possibility they might have been needed to bomb exile bases. 26

President Kennedy’s assassination brought a halt to CIA-directed sabotage, but it had little immediate impact on the autonomous operations. President Johnson was briefed at a December 19 meeting in the White House on the agency’s covert programs. According to the CIA chronology, “in the course of the briefing which included the autonomous operations, Higher Authority asked the cost of these operations and he was informed the total was about $5,000,000. He also asked the cost of Cuban operations for the current year and was informed it was about $21 or 22 million.” 27

Six weeks after becoming president, Johnson was presented with an exhaustive review of the covert action program against Cuba that defined the autonomous operations as “intended to provide a deniable activity, a means of supplementing and expanding our covert capability and a means of taking advantage of untapped political and resistance resources of the exile community.” The review, declassified in 2001 but still partially censored under the JFK Assassination Records Review Act, went on to describe the program as “one that now includes [censored] autono

mous groups whose credibility as to autonomy is strengthened by the facts that:

They are led by men whose prominence and status in the Cuban exile community makes plausible their access to funds, equipment and manpower quite independent of the U.S.;

[Censored] are based in the Caribbean area outside of U.S. territory;

[Censored] have natural, willing allies in power in several Latin American countries;

[Censored] are Cuban and employ Cuban nationals exclusively;

Every item of financial and logistic support has been handled in a manner as to provide maximum protection against proof of CIA or U.S. participation.

The initial aim of these operations is to strengthen the will to resist by increasing the tempo of subversion and sabotage largely maintained until now by CIA; the eventual aim is to take the fight from the coastline to the interior of Cuba.

The disadvantage of our autonomous operations is that it is necessary to accept a lower order of efficiency and control than would be considered acceptable in CIA-run operations. 28

In fact, the review appeared to be somewhat premature. Neither of the autonomous groups had yet become operational, and Ray had not yet found a country to host his operation.

Shortly before President Kennedy’s assassination, a new element entered into the equation and reopened debate on the administration’s Cuba policy. An arms cache was discovered November 1 on a Venezuelan beach. An investigation determined the cache was left by Cuban agents and meant to aid Venezuelan guerrillas in an effort to disrupt upcoming national elections. With a good case now to be made before the Organization of American States [OAS] for further isolating the Castro government, the new Johnson administration was forced to decide whether to pursue an overt “clean hands” policy or to continue its two-track policy of political pressure and covert action. If U.S.-sponsored covert action continued, it could damage the case for isolation and make Washington vulnerable to accusations of hypocrisy before an OAS Foreign Ministers meeting convoked for July by Venezuela under the Rio Treaty.

At an April 7, 1963, White House meeting to review covert action against Cuba, an informal decision was made to continue a stand-down

of CIA-controlled sabotage activities imposed in January, a decision influenced by the upcoming OAS meeting as well as the Soviets’ prospective turnover of SAM [surface-to-air missile] missile sites on the island to Cuba. It was decided that nothing should be done about the Artime and Ray autonomous groups which were about to become operational. 29 Two days later, Bundy, Richard Helms, and an unidentified third person met to share their concerns about the Artime and Ray operations and these operations’ implications for the upcoming OAS meeting. They concluded that Artime could not be dissuaded from mounting his first action and briefly considered using a U.S. Navy destroyer to halt the operation, before abandoning the idea altogether. “Mr. Bundy capsuled the problem by saying his worry was whether an Artime attack would give the U.S. a hypocritical image when out of the other side of its mouth the U.S. was plumping for votes at the OAS to outlaw subversion and armed attack.” 30

This was the latest in the ongoing debate between the pros and cons of the autonomous groups. Desmond FitzGerald had defended them in a March 6, 1964, letter to Bundy reviewing the CIA’s covert action program against Cuba. In his appraisal of the autonomous groups, FitzGerald said:

As you know, again as part of the June plan, we are supporting two ‘autonomous’ exile groups headed respectively by Manuel Artime and Manolo Ray. In both cases we have gone to maximum lengths to preserve the deniability of U.S. complicity in the operation. Artime, who now possesses the greater mechanical and paramilitary apparatus, has required a good deal of hand-feeding although still within the context of deniability. He will probably not be ready for his operations against Cuba before April or May of this year. He possesses most of his hardware and maritime equipment and has negotiated geographical and political bases in Central America. Manolo Ray has been handled on a much more independent basis. We have furnished him money and a certain amount of general advice. He does not possess the physical accoutrements that Artime has and is probably not as well equipped in terms of professional planning. Ray has a better political image inside Cuba among supporters of the revolution and has recently acquired, according to reports, some of the other left-wing exile activist groups such as Gutierrez Menoyo and his Second Front of the Escambray. He is said to be ready to move into Cuba on a clandestine basis late this spring. His first weapon will be sabotage inside Cuba, apparently not externally-mounted hit-and-run raids.

If U.S. policy should demand that the ‘autonomous’ operations be suspended, we could of course cut off our support immediately. Artime and

his group might or might not disintegrate at once. Manolo Ray almost certainly would continue. Both groups are based outside the United States and our only real leverage on them is through our financial support but withdrawal of this support would probably be fatal to their operations in time. A cutoff of this support, even though this support has been untraceable in a technical sense, would have a considerable impact within the exile community. U.S. support is rumored, especially in the case of Artime, and the collapse of the only remaining evidence of exile action against Castro would hit the exile community hard which is what it in turn would do to its favorite target, U.S. policy. The exile of today, however, appears to have lost much of his fervor and, in any case, does not seem to have the capacity for causing domestic trouble which he had a year or two ago. The Central American countries in which the exile bases exist would be greatly confused, although we have carefully never indicated to the governments of these countries any more than U.S. sympathy for the ‘autonomous groups.’ 31

The FitzGerald letter was submitted to the Special Group on March 30 along with a memorandum entitled “Status Report on Autonomous Cuban Exile Groups,” to alert the members that both Ray and Artime were about ready for action. On May 13 Artime’s commandos hit the Puerto Pilon sugar mill in Cuba’s southern Oriente Province. It was the first action after more than a year of preparation, damaging warehouses and reportedly destroying seventy tons of sugar, valued at about one million dollars. Five days later, on May 18, Ray departed for his long-awaited infiltration into Cuba, amid what one CIA report called “a major publicity campaign sparked by the New York Times” 32

The Times ran front-page stories by Tad Szulc that focused on Ray for three consecutive days. The first appeared May 19 with a dateline from “Somewhere in the Caribbean.” It featured an interview with Ray about his aims and ran under the headline: “Ray Plans to Use Cuban ‘Will’ As Means to Overthrow Castro.” The second article, on May 20, was headlined “Anti-Castro Fight Starts New Phase.” In it Szulc proclaimed “the most important single operation now being undertaken is that of the Revolutionary Junta. The leader of the junta, Manuel Ray, was reported today to be somewhere in the Caribbean, presumably preparing to land secretly in Cuba in order to initiate what he has described as the long and painstaking process of hammering together an effective underground organization.” The third, on May 21, was headlined “Exiles Proclaim Anti-Castro War and Urge Revolt.” It referred to proclamations issued by the organi

“LET CUBANS BE CUBANS’’

zations headed by Ray and Gutierrez Menoyo and went on to say that “both proclamations were timed for the arrival on the island today of Manuel Ray, the top leader of the Revolutionary Junta, and Maj. Eloy Gutierrez Menoyo, the Second Front commander.” Szulc’s story was accompanied inside the paper with the text of Ray’s proclamation and a profile of Ray.

The articles prompted a three-page May 23 cable from Shackley’s JMWAVE station in Miami to Washington with the subject: “Impact in the Miami Area of Recent Tad Szulc Articles on Manuel Ray Rivero.” It began by saying “the following roundup on the impact in the Miami area of Tad Szulc articles in the New York Times of 19, 20, and 21 May 1964, which have been oriented in a direction which fully propagandizes Manuel Ray Rivero . . . and his anticipated accomplishments in Cuba . . .” It went on to say “the majority of the exile colony has interpreted the New York Times s exhaustive coverage to be a reflection of U.S. intent to modify Ray’s existing public image and simultaneously to make it clear to all Cubans that Ray has become a chosen instrument around which the U.S. plans to carry out not only the liberation but the reconstruction of Cuba.” 33

The New York Times was not alone in resorting to a bit of jingoism. “‘War On,’ Refugees Proclaim,” read a May 21 page-one headline in the Miami Herald. A day earlier, on May 20, another page-one headline declared: “Cuba Girds for Raids By Exiles.” And on May 17, one Miami Herald article began with considerable hyperbole, as it turned out:

Two Cuban exiles, one a soft-spoken idealist and the other a machete-slim fighter, today are in or near Cuba to fight or die. Both were veterans of the Cuban revolution against Dictator Fulgencio Batista, and now of the fight against Premier Fidel Castro.

Manuel Ray, an engineer who would rather build than kill but organizes both exceptionally well, plans an internal resistance movement which he hopes will snowball into open fighting or possibly a coup.

Eloy Gutierrez Menoyo, who hates oppression and loves battle with equal vigor, plans guerrilla warfare which he hopes will succeed in the pattern Castro himself once set.”

The article concluded:

The promised time for the jumpoff of Ray and Menoyo into Cuba comes at the end of a week during which the Cuban exile community has gorged itself on rumors to the burping point.

However, it has served to make U.S. officials more uncomfortable than anyone else.

As reports of command raids, impending uprisings, infiltration and all manner of heroics ricocheted around Miami, officials privately worried for two reasons:

RUMORS and exaggerations inflame the exiles, causing them to uproot themselves from jobs and homes, and add to the sizable problem of resettlement.

THE IMPLICATION of such reports being distributed here that the U.S. may be secretly involved, which the officials emphatically deny.

Fuel was added to exile excitement by a raid last week by Manuel Artime’s Movement for Revolutionary Recovery, which attacked a sugar mill on the south coast of Oriente Province.

f

CHAPTER

M ay 20, 1964, proved to be more of a last gasp than another new beginning in the anti-Castro campaign. Neither Ray nor Menoyo lived up to their advance billings, their efforts ending in ignominy, not triumph. Menoyo, at least, reached Cuba. Ray, after his much-ballyhooed departure, succeeded only in reaching Anguilla Cay in the Bahamas. There, on May 30, the boat he planned to use for the final infiltration run to Cuba developed motor trouble. JURE representatives scurried to find a replacement boat along with an additional supply of drinking water, but British authorities (the Bahamas was yet a British possession) got there first, seizing a cache of weapons and explosives and arresting Ray and his crew of seven. They were taken to Nassau where each paid a minimal $14 fine for illegal entry and were released. Ray’s “crew” included two Time-Life photographers, Andrew St. George and Tom Duncan, suggesting to some that his ill-fated adventure may have been more of a publicity photo op than the opening battle in a new war. 1 Ray was down but not yet out. Menoyo, as noted earlier, dropped from sight for several months, resurfacing in late January 1965 when Cuban authorities announced his capture, along with three companions, in Oriente Province. He served eighteen years in a Cuban prison, returning to Miami after his release to become an advocate of accommodation.

In Washington the new Johnson administration was having trouble making up its mind about the autonomous groups. Much of the ambivalence centered on the upcoming mid-July 1964 OAS meeting to deal with the Cuban arms cache found in Venezuela. The hope was that the meeting would result in tightening Cuba’s hemisphere isolation, leading to military intervention if additional caches were found or similar activities continued. Second, there were widespread reports that the Soviets were about to turn over SAM sites to the Cubans. If that happened, there was fear Castro might counter a sabotage raid with an effort to shoot down a U-2 overflight. Still another worry was the reaction of the Cuban exile corn

munity if support for the autonomous groups was terminated. These arguments were set forth in a June 3, 1964, report by the CIA: A Reappraisal of Autonomous Operations. 2 The author was not identified, but presumably it was heavily influenced, if not written, by Desmond FitzGerald. The paper’s slant clearly favored continuation of support for the autonomous operations, despite the State Department’s contrary view and widespread anathema for the program among many of the CIA operational people involved with it.

“It has been suggested that a reappraisal of autonomous operations would be in order if, as a result of an OAS resolution on the Venezuelan arms cache, aggression is to be redefined to include subversion,” said the study. “It is argued that the U.S. should, if it is to exploit the OAS resolution, not itself engage in the proscribed activities. The U.S. would have to adopt a ‘clean hands’ position vis-a-vis Cuba and this state of cleanliness must be maintained indefinitely if the U.S. is to remain in a position to apply sanctions against Castro should he be again caught red-handed.”

The reappraisal then discussed considerations that would affect U.S. support for the autonomous groups. It opened with the assumption “that it remains U.S. policy to get rid of Fidel Castro by acceptable means. If this premise is correct the first task of the policymaker in framing the issues herein presented, is to balance the two courses of action proposed—i.e. (a) a continuation of autonomous operations and (b) an exclusive reliance on OAS sanctions in terms of their effectiveness in achieving our basic purpose.”

When the CIA’s integrated covert action program began, the appraisal noted, it had been agreed that it should be given an eighteen-month test, but “despite the truncated nature of the program it appears to us that there have been many indications of success.” Cited among the successes was the establishment of a “direct correlation between the series of minor sabotage operations during the late part of 1963 and a rise in internal resistance by sabotage. The Pilon raid [by Artime] and news of Ray’s plans to return to Cuba has again set off military alerts and other internal measures not observed in Cuba since the October 1962 missile crisis.”

The appraisal made the case for continuation of the two approaches, covert and “clean hands,” without choosing either. “Having already denied ourselves unilaterally controlled raiding actions and having taken precaution not to leave our fingerprints on the autonomous operations, may we not proceed along both tracks in their current direction, denying stoutly our involvement in the illegal activities of achieving our national

purpose?” the report asked, followed by an answer. “We are certain to be accused of responsibility for other exile activities in which we are not involved. Our innocence will be as difficult to establish as would be our involvement in the case of our autonomous operations.”

The reappraisal expressed fear that suspension of support for the autonomous program would assuredly become known in the exile community, and seen as “a further indication that the U.S. is no longer interested in the active liberation of Cuba and is moving in the direction of rapprochement and accommodation with the Castro regime.” The potential for adverse domestic political and international repercussions was raised, with particular interest in impact on the Nicaraguan and Costa Rican governments “who have afforded these groups base facilities on their soil.” Ending support might provoke the groups to “step up these raids, in defiance of U.S. wishes if necessary” and could even lead to “a choice of activities on the part of these groups that would have a higher ‘noise level’ than at present.” Finally, the report argued, a consequence of the “clean hands” principle would affect all covert activities, not just sabotage raids.

The appraisal concluded:

Termination of U.S. support for the autonomous groups will not necessarily assure the cessation of externally mounted commando raids on Cuba.

In fact, it is likely that the first reaction of the autonomous groups will be to conduct ‘higher level’ activities than at present including, perhaps, revelations of past U.S. support. There may also be exile raids with which we have no connection, e.g., the SNFE or Alpha 66—for which the U.S. would automatically be blamed.

Adoption of the ‘legal track’ would have ramifications for covert operations extending far beyond autonomous raiding actions. Maritime infiltration/exfiltration for intelligence and caching operations, both autonomous and unilateral CIA, would have to be included in the ban if the ‘clean hands’ principle is to be applied in a consistent and meaningful manner.

The cessation of autonomous commando operations—the only remaining external sabotage activity since unilateral CIA operations were stood down in January 1964—would effectively kill the remaining chances of carrying out the objectives of the Integrated Covert Action Program initiated in June 1963.

While the cost would be high, it might well be worth the sacrifice if the U.S. is prepared for armed intervention in Cuba if the OAS will unequivocally support it.

A day later, on June 4, Chase told Bundy that the more he saw of the autonomous operations “the less I like them. . . . These raids probably double our very poor chances of overthrowing Castro.” 3 The Special Group put the issue on the agenda for its June 18 meeting. In advance of the meeting, Chase offered some thoughts to Bundy. “There are,” he said, “a number of disadvantages to the status quo. ... At best these raids will make it tougher to keep the lid on Cuba between now and [U.S. elections in] November. This is just the sort of thing that can evoke a highly irrational response from Castro. As things stand, Castro seems convinced that we are tied to the raids—as indeed we are.” Chase also raised the possibility that the raids could “touch off a U-2 shootdown and a first class Caribbean crisis.” Finally, he told Bundy, the State Department believes the “autonomous raids would make more difficult the enforcement language in the OAS resolution, i.e., our own hands should be clean.” Alternatively, Chase suggested, “(a) We can make a real effort to stop the raids.

. . . (b) We can search harder for an alternative to the U-2. ...(c) Using our support as leverage, we can try to discourage the exile groups from making raids of the higher noise-level variety. ...(d) We can cut off all U.S. ties with these exile groups.” 4

The Special Group took the easy way out, choosing to maintain the status quo, as “none of those present appeared to feel that it was either realistic or practical to sever connections with or to withdraw support from the two principal emigre organizations, those of ARTIME and RAY. It was agreed that ARTIME should be convinced that his greatest value was in his survival as a continuing psychological threat in being.” 5

Chase also advised Bundy that “Manolo Ray recently asked the U.S. Government for three things—(a) a special grant, (b) our influence with the Puerto Ricans getting them to allow Ray to move a boat from Puerto Rico, and (c) our assistance in getting the Dominican Republic to allow Ray to establish a base in that country.” There is no indication whether any of the three requests were acted on, but later documents indicate Ray did establish a base in the Dominican Republic sometime in the latter part of 1964. 6

In July the OAS condemned Cuba for aggression. A State Department analysis summarized the OAS action: “planting an arms cache in Venezuela in connection with a Cuban supported plan to overthrow the Venezuelan Government—and resolved to impose sanctions against the Castro regime. Reaction to the move in the free world ranged from enthusiastic support in most of Latin America to skeptical deprecation in parts

of Western Europe.” The analysis predicted the sanctions would “help to disrupt subversive activities in Latin America and to further discourage Castro from pursuing these activities” but “have little immediate effect upon the Cuban economy.” On balance, the OAS action was seen “as a substantial victory for the US and Venezuela.” 7

With attention focused on preparation for the OAS meeting, Ray made at least two more aborted infiltration attempts of Cuba. He recounted his efforts in a visit to G. Harvey Summ, head of the Miami office for the State Department’s coordinator of Cuban affairs. The visits apparently were an attempt to persuade the U.S. government “that his recent failures have not deterred him in his dedication and determination to attempt light spark of internal resistance against Castro forces.” He told Summ that as he left for Cuba from Key West on July 11, the Coast Guard had stopped him, which caused him to abandon his attempt. Summ responded that the Coast Guard was doing its duty, and “one could speculate that had he proceeded on July 11 he might have run into some other kind of bad luck.” Ray could avoid such difficulties in the future, Summ said, by “operating from somewhere else.” Ray was to attempt another infiltration from Key West on July 13. He said he had gotten within five to eight miles of the Cuban coast, when one of his boat motors broke and could not be repaired. He returned to Florida. “Obviously disappointed at failure, Ray nevertheless maintained that he would soon try again. Not sure of how or from where,” Summ reported to Washington. 8

Ray’s failure to meet the expectations he had created led to a significant loss of credibility among exiles and defections from his organization. The JURE survived until 1968, but nothing indicated it ever did anything. Neither was there ever any sign of the broad underground network in Cuba that Ray claimed to have. He did, apparently, eventually establish a base in the Dominican Republic and acquire the Venus, a 110-foot Panamanianregistered vessel that became the object of an internal JURE dispute. Ray reportedly received U.S. funding of $75,000 for October-December 1964 to underwrite relocation of the group’s activities outside U.S. territory. 9

Intelligence reports indicate he again planned to infiltrate Cuba in December 1964 to reconnoiter for a commando raid early in 1965. As had become routine with Ray, it didn’t happen. The infiltration was rescheduled for February 1965. Still nothing happened. “All the men at JURE’s camp in the Dominican Republic are a little disgusted because they do not think that Ray will ever go to Cuba. They have given him 5

February as a deadline,” read one intelligence report. The report author added his own comment: “If Ray does not leave for Cuba by this date, he will probably lose all his men. They are all anxious to see action but Ray has been giving them nothing but promises and plans.” 10

Shortly after, Jose Ricardo Rabel, the captain of the Venus, along with other crew members, plotted to take control of the vessel, two Boston Whalers, and all the weapons at the Dominican base, and carry out a raid of their own. A few days later, according to an intelligence report, “Ray, who thinks the plotting has subsided, gave Rabel $1,000 on 30 January to cover boat expenses, and $50 to each man at the base.” 11 The payoffs apparently quelled the revolt.

Artime was bedeviled by problems of a different nature. Rumors circulated of his possible misuse of U.S. funding, prompting a look at the group’s finances. The results were reported in a July 16, 1964, CIA memorandum to the 303 Committee (as the Special Group was now called). No evidence of fraud was found, but the memo provided a revealing look into Artime s operation. From June 1963, when the program was approved, until June 30, 1964, a total of $4,933,293 had been spent in support of his operation. At the time of the memo, Artime was receiving a monthly subsidy of $225,000 for normal operating expenses. Unusual or extraordinary costs such as purchase of additional boats and construction equipment or major ship repairs are funded separately as required.” The memo said the figure for the monthly subsidy was based in part on “a payroll of $95,000 for 385 men, subsistence of $27,000 based on $3.00 per day per man for some 300 men in training camps, $47,000 for aviation and maritime operations and maintenance, $15,000 for camp maintenance in both Costa Rica and Nicaragua, and $12,000 travel expenses.”

The investigators concluded, “Except for financial losses sustained as a result of poor management, the funds have probably been applied for the purposes for which they were intended.” The memo noted that Artime was in charge of a multimillion dollar operation, and “his compensation on a GS-13 scale appears equitable in those conditions. We have found no hard intelligence to support the allegation that ARTIME is leading a life of ostentation and affluence. We have found no evidence of defalcation.” It added, however, that the “possibility is ever present in a program of this magnitude and under the existing rules of engagement.” 12 Rafael Quintero recalled years later that he and Tito Mesa, the exile businessman

who handled the operation’s finances, estimated about $7 million had been spent during the life of Artime’s autonomous operation. 13

Meanwhile, an influential new player emerged in early summer 1964 among the exile “action” groups vying for U.S. backing. Known as RECE, the Spanish acronym for Cuban Representation in Exile, its godfather was Jose “Pepin” Bosch, wealthy chief of the Bacardi rum company. He had bankrolled a worldwide referendum, with forty thousand Cubans participating, to select a five-member “war board.” The most prominent members were its chief, Ernesto Freyre, an exile lawyer instrumental in negotiating release of the Bay of Pigs prisoners, and Erneido Oliva. Disillusioned with President Johnson’s decision to suspend the program for Cubans in the U.S. military, Oliva resigned his army commission in May to become chief of RECE’s military operations committee.

A profile of Oliva in the Miami Herald shortly after he became RECE’s military chief began by noting that “if his success can be measured by the respect he commands within the oftimes internally torn Cuban exile colony, Fidel Castro’s days are numbered.” It described him as “a professional soldier who preaches brotherly love with the conviction of a man of the cloth . . . emerging as the newest of a handful of leaders upon whom Cuban exiles hang their hopes for a return to the island.” 14

Born of a black working-class Cuban family in the town of Aguacate, between Havana and Matanzas, Oliva joined the Cuban army under Batista, but wasn’t tainted by action against Castro. When Batista fell, Oliva was in Panama as an instructor at what was later known as the U.S. Army’s School of the Americas. He had returned to Cuba in midDecember 1958 to get married, but was back in Panama when, early on New Year’s Day of 1959, he heard the news of Batista’s flight. Oliva and Grace, his new bride, returned home from a New Year’s Eve party, only to be awakened by a 4 a.m. telephone call from a School of the Americas’ secretary alerting him to events in Cuba. He said, “OK,” and went back to sleep, awakening again ten minutes later when the import of what he had heard dawned on him.

Hearing nothing from Havana, Oliva said he continued working as an instructor until sometime in February, when “Raul Castro learned there was a Cuban officer in Panama. When they called [the school] and asked, ‘Who is there?’ And they said ‘a lieutenant of the Constitutional Army and he’s an instructor.’ The secretary told me that they said I had to come back right away; they didn’t want any Cuban officers in Panama.” The school told him he had only two choices: return to Cuba or go into Pan

ama City and ask for asylum. Oliva discussed the situation with his new wife, deciding to return to Cuba “because there is nothing that I have to be afraid of.” He left Grace in Panama. On his return to Cuba in late February, he had to stop first in Costa Rica. There, “someone spotted me in the airport and asked ‘Where are you going?’ and I said I was going back to Cuba. And they said, ‘No, you are not. You are a war criminal.’ There were other Cubans in the airport and when they saw me they started shouting, ‘war criminal, to the wall,’ and I said, ‘Guys, I am going to Cuba.’ The police had to come and pull me from there and take me to the plane. That was a show.”

When he arrived in Havana, Oliva was taken to a small security room in the airport and questioned about what he was doing back in Cuba. He told his questioner he had been called back by Raul Castro, or his chief of staff. They told him they would check him out, and “I thought, ‘Oh, my God, I am in trouble.’ ” His luggage was searched and his Cuban military uniforms discovered. He showed them an identification card from the U.S. Army’s school in Panama. He was kept at the airport from 4 p.m. to 10 p.m., then taken to La Cabana, the fortress on the Havana waterfront where summary executions of Batista army men, some of which Oliva had seen on television in Panama, had been taking place.

“That’s what was in my mind,” Oliva recalled, “but instead they took me to the headquarters and there was Che Guevara; that was the first time I had ever met him. He was really very kind to me, so I don’t have any complaints. He welcomed me and said, ‘We don’t want to have any relationship with the Americans. I have here a report that you are a professional soldier, but never have fought against us . . . blah, blah, blah, so, no problem. But instead of being a first lieutenant, you are now a second lieutenant because you have not done anything for this revolution. Batista promoted you to first lieutenant, so now you are a second lieutenant.’” Oliva was assigned to a military base in Managua, a few miles south of Havana, where he worked with Juan Almeida—who had fought with Castro in the Sierra Maestra—advising an artillery battalion.

Oliva had cautioned his wife to remain in Panama until he called her because of the still uncertain course of events in Cuba. About two weeks after his arrival in Managua, Almeida called him to his headquarters where Grace was waiting, because “she said she was desperate” in Panama. Soon the difficulties began, said Oliva. From Managua, he was assigned to the revolution’s new agrarian reform program, “and I saw the Communists taking over. Everywhere I went the party clique was in charge. I said, This is it, and I started working with the underground.”