Three

Capturing Carbon

Cough. Cough. Cough. Standing at your open door, you wipe your hand across your watery eyes. You cough again as you inhale thick, hazy air, and your throat becomes dry and tickly. Your eyes sting and your nose wrinkles as it encounters the foul smell of car exhaust and other pollution.

You are in a city with some of the unhealthiest air in the world: Beijing, China. Not all days are as bad as this one. On some days, depending on the wind direction, the air over Beijing is mostly clear and sun shines across the beautiful skyline. But on other days, when the wind shifts, air pollution from nearby industrial plants blows into the city and hovers overhead. The dark haze makes it difficult to see, swallowing up the tops of buildings, cars, and even people. On days like that, the air quality index (AQI), a measure of the amount of pollution in the air, can reach as high as 300 to 500. This means there are 300 to 500 micrograms of particulate pollution (tiny particles and liquid droplets) in every 35 cubic feet (1 cu. m) of air. Compare that to a healthy AQI reading, which is 0 to 50.

Beijing is not the only city with pollution problems. Los Angeles, California; Delhi, India; Jubail, Saudi Arabia; and many other cities have high levels of air pollution. But Beijing has some of the worst pollution on Earth. The mountains that surround the city form a container that holds in polluted air. On the worst days in Beijing, the AQI tops 700.

In Tiananmen Square in Beijing, a young woman uses her smartphone while military guards stand at attention. In Beijing thick smog often limits visibility and most city dwellers wear face masks to reduce the amount of pollution entering their lungs.

Some of the air pollution comes from industrial plants, and some of it comes from cars. By burning fossil fuels, factories and cars release carbon monoxide, hydrocarbons, nitrous oxide, and other gases into the air. The particulates, or tiny particles, in these gases mix with moisture in the air to form smog, a name combining the words smoke and fog. Sometimes sunlight reacts with hydrocarbons and nitrous oxide to form ozone and other gases, a type of pollution called photochemical smog. Both types of smog can irritate people’s noses, eyes, and throats and damage their lungs. People who are regularly exposed to high levels of air pollution can develop asthma, emphysema, and heart problems. Extremely heavy smog can kill plants and even humans. On smoggy days, many of the seventeen million residents of Beijing wear masks over their mouths and noses to reduce the amount of pollution entering their lungs.

Health officials in Beijing and elsewhere recommend that citizens stay inside on smoggy days and use air purifiers to clean indoor air. This is not a permanent fix, however. It doesn’t clean up pollution, and it doesn’t reduce the amount of heat-trapping carbon dioxide entering the atmosphere. Switching to renewable and alternative fuels—such as solar power, wind power, and hydropower—is a step in the right direction. These energy sources don’t add more carbon to the air—but they don’t remove it from the air either. And that’s exactly what some scientists think we need to do to fight climate change: actively remove excess carbon dioxide from the air.

If a Tree Falls in the Forest

A natural way to pull carbon dioxide from the air is with reforestation, or planting forests full of trees. Whether it’s a tropical rain forest in South America, a dense forest of evergreens in Canada, or stands of redwoods in California—any type of forest will capture carbon. That’s because trees, like all plants, absorb carbon dioxide during photosynthesis.

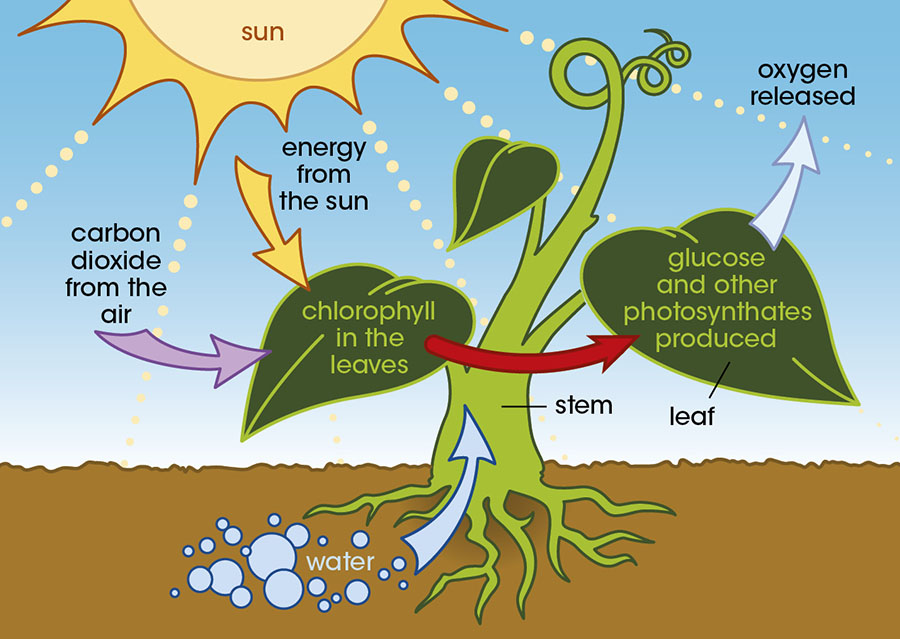

PHOTOSYNTHESIS

Trees and other plants take in carbon dioxide from the air and use it to make energy. Widespread deforestation has reduced the number of trees absorbing carbon dioxide this way. We could reverse this process and reduce atmospheric carbon dioxide levels by planting trees to replace those that have been destroyed.

Besides absorbing carbon dioxide, healthy forests are vital ecosystems—communities of living and nonliving things that interact with and depend on one another. Thousands of species of plants live in forests. Thousands of species of animals make their homes, raise their young, and find food inside forests. Forest trees protect the soil by sending their roots deep into the ground. The networks of roots hold the soil in place and prevent it from eroding, or washing away, during rainstorms. Trees also capture rainwater in their leaves, which keeps excess water from hitting the ground and causing floods. Trees play a crucial part in Earth’s water cycle as well. Water from the soil enters trees through their roots, moves through their trunks and branches, and evaporates from their leaves. The water eventually returns to the forest soil as rain and snow and begins its cycle again.

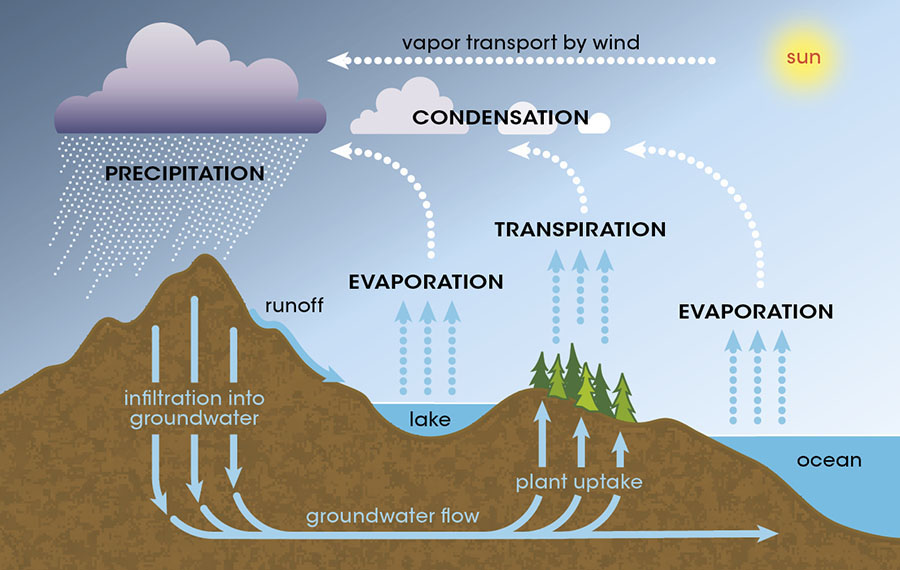

THE WATER CYCLE

By taking up groundwater through their roots and releasing it through their leaves, trees play a key role in Earth’s water cycle. Deforestation has disrupted this cycle and also increased atmospheric carbon dioxide levels.

Forests also play a significant role in human society. Did you read a book or newspaper today? Pin papers onto a cork bulletin board? Blow your nose? If so, you used a product derived from a tree. Manufacturers use wood from trees to make paper and facial tissue. They create many medicines, cosmetics, waxes, oils, and other products from the leaves, bark, and sap of trees.

Even though trees are valuable to humans, forests are disappearing at an alarming rate. Since the mid-twentieth century, loggers have cut down more than half of the world’s forests. According to the United Nations Food and Agriculture Organization, people destroy almost 18 million acres (7.3 million hectares) of forests each year. That’s about the size of Panama or about half the size of Illinois. It equals approximately thirty-six football fields full of trees destroyed every day. Humans cut down trees for many reasons: to create products from wood, leaves, and bark; to build roads through forested land; and to make room for houses, farms, and ranches.

When humans cut down trees, they don’t just destroy forest ecosystems. They also change the carbon cycle. Forests are a type of carbon sink, a natural system that removes carbon from the atmosphere and stores it. Oceans, soil, and fields full of plants are also carbon sinks. According to the US Forest Service, American forests absorb enough carbon to offset between 10 and 20 percent of all US fossil fuel emissions per year. The more forests we have on Earth, the more carbon dioxide they remove from the air. But that also works in reverse. The more trees we cut down, the less carbon dioxide trees can remove from the air. With more heat-trapping carbon dioxide in the air, the more global temperatures rise.

The rain forest surrounding the Amazon River and its tributaries (feeder rivers) in South America covers an immense 2 million square miles (5.2 million sq. km) of land. The Amazon rain forest is one of the largest carbon sinks in the world.

But between 1978 and 2016, humans destroyed more than 289,000 square miles (749,000 sq. km) of Amazon rain forest to build roads and farms, to harvest wood, and to mine for minerals under the soil. This rapid elimination of the rain forest released massive amounts of heat-trapping carbon into the atmosphere, accelerating climate change. And destruction of large numbers of trees hurt the forest ecosystem. With fewer trees to capture rainwater, prevent erosion, and take part in the water cycle, parts of the forest began to dry out.

For many years, environmentalists have been sounding the alarm about destruction of the Amazon rain forest. In 2004 governments of nations that are home to the rain forest—Ecuador, Peru, Bolivia, and Brazil—started taking steps to protect it. They began limiting the numbers of trees that could be cut, declaring some areas off-limits to logging, and planting new trees to replace those cut down.

Since the late 1970s, humans have destroyed vast sections of the Amazon rain forest. Areas cleared of trees, such as this one in Peru, can no longer function as carbon sinks.

Will these efforts help prevent climate change? According to Dr. Richard Houghton, an ecologist at the Woods Hole Research Center in Massachusetts, the answer is a resounding yes. Houghton believes that simply stopping deforestation in Earth’s tropical regions would have monumental impact. For example, if the approximately 31.5 million acres (12.8 million hectares) of trees currently being cut down in tropical regions each year were instead left intact, they would absorb 1.1 to 2.2 billion tons (1 to 2 billion metric tons) of carbon per year. As they grew, they would absorb even more carbon per year, between 1.1 and 3.3 billion tons (1 to 3 billion metric tons). Moreover, if trees could be replanted on the more than 1.2 billion acres (500 million hectares) previously deforested by humans, those trees would absorb another 1.1 billion tons of carbon per year. Do the math:

- 1.1 to 2.2 billion tons from not cutting down trees +

- 1.1 to 3.3 billion tons if the trees that are not cut down are allowed to grow to maturity +

- 1.1 billion tons from replanting the previously decimated 1.2 billion acres.

The result is absorption of between 3.3 and 6.6 billion tons (3 to 6 billion metric tons) of carbon per year. Houghton summarizes: “That’s equivalent to 30–60% of current emissions of carbon from fossil fuel use.” The numbers show that humans could make a significant dent in global carbon emissions—and potentially slow climate change—by eliminating deforestation and implementing widespread reforestation.

Yet many governments and businesses are reluctant to halt deforestation. Loggers cut down trees so that businesses can make products that consumers want to buy. For instance, palm trees produce palm oil, which is used to make thousands of products—everything from snack foods to shampoos to ice cream. Because palm oil is a big moneymaker for many companies, loggers continue to cut down palm trees. Businesses aren’t likely to stop practices that make them a lot of money, but as the perils of climate change have become more apparent, attitudes are starting to change. For example, to help fight climate change, major food companies such as Hershey and Kellogg’s have announced they will buy palm oil only from palm tree plantations that practice reforestation.

Schools, governments, and nonprofit organizations have also begun reforestation efforts. In Brazil the Planeterra Foundation planted more than 450,000 trees from 2009 to 2012. The organization continues to work with Trees for the Future (TFTF), a US-based reforestation program that has been planting trees in Brazil since 1989. And students in many parts of Africa and South America have joined school-based reforestation programs, raising tree saplings for three to five years until they are strong enough for replanting. Students learn the importance of forests as carbon sinks and study how strong tree root systems can prevent erosion and reduce flooding. They also learn eco-friendly planting and harvesting methods along with ways to promote biodiversity, or the growth of many different plants and animal species in the same ecosystem.

These efforts are a start. But as Houghton’s numbers show, it will take more than voluntary programs to significantly offset carbon emissions from fossil fuels. It will take wide-scale, global reforestation efforts to make a difference.

A young man tends to mahogany tree seedlings at a nursery in Brazil. With widespread reforestation efforts, groups hope to reduce atmospheric carbon dioxide levels and also restore forest ecosystems.

Carbon-Neutral Biomass

Humans can also fight climate change—or at least keep it from getting worse—by using plant-based biomass fuels. Plant biomass includes leaves, sticks, grass, wood chips, and bark taken from recently living plants and trees. Because plants practice photosynthesis and absorb carbon dioxide, all these materials contain carbon. When biomass is burned as fuel, it releases this carbon back into the atmosphere.

Wait a minute! Fossil fuels also come from formerly living organisms and also release carbon dioxide when they are burned. So why is biomass more eco-friendly? It’s a matter of time. When we burn biomass plants, we release carbon that was recently removed from the atmosphere—during photosynthesis taking place when the plants that provided the biomass were alive. With biomass, the amounts of carbon taken from the atmosphere and the amount released back into the atmosphere cancel each other out. This makes biomass carbon neutral. Fossil fuels, on the other hand, removed their carbon dioxide from the atmosphere millions of years ago. When we burn them, nothing in existing natural processes offsets the extra carbon they release. So fossil fuels are not carbon neutral but instead add carbon to the total amount in the atmosphere.

From Carbon Neutral to Carbon Negative

Since biomass fuels are carbon neutral, they don’t actually reduce the amount of carbon dioxide in the air. But some engineers envision a system called bioenergy with carbon capture and sequestration (BECCS) that would capture the carbon released by biomass fuels and sequester it, removing it from the carbon cycle and thus making a dent in climate change.

A truck unloads wood chips at a biomass warehouse in the United Kingdom. When the trees that provided the chips were alive, they absorbed carbon dioxide during photosynthesis. When the chips are burned for fuel, they will release that carbon dioxide. The process is carbon neutral, since the amount of carbon released cancels out the amount of carbon absorbed. But if machinery captures the carbon dioxide when the chips are burned, the process is carbon negative.

Here’s how such a system would work. First, farmers grow trees, which are then cut down and cut up into tiny wooden pellets. Power plants burn the pellets to spin turbines that generate electricity. As the pellets burn, machinery captures the carbon dioxide in the emissions and compresses it. (Compressing gas reduces its volume, making it easier to transport and handle.) The compressed gas can be stored long-term in large tanks or sold to businesses that use carbon dioxide in manufacturing. Such businesses include beer and soda companies, which use carbon dioxide to add fizz to their beverages; greenhouses that use the gas to promote plant growth; and companies that turn carbon dioxide into fertilizer and dry ice. BECCS would be carbon negative—it would remove more carbon from the atmosphere (through the growth of biomass and the capturing of carbon) than would be released into the atmosphere when the biomass is burned.

Can biomass become a long-term, sustainable alternative fossil fuel? Energy expert Daniel Kammen of the University of California–Berkeley believes so. He states, “Biomass, if managed sustainably can provide the ‘sink’ for carbon that, if utilized in concert with low-carbon generation technologies, can enable us to reduce carbon in the atmosphere.”

Carbon Capture

While no BECCS plants are in the works, some companies are making plans to capture carbon from power plants that burn fossil fuels. For example, the Petra Nova Carbon Capture Project, a joint venture between the US Department of Energy and private industry, will capture carbon from a coal-burning power plant in Houston, Texas. The project is designed to capture 90 percent of the carbon dioxide from the plant’s emissions. That carbon dioxide will then be compressed and shipped to oil fields in the Houston area, where it will be used to help release oil from old oil wells.

Capturing carbon from power plants is straightforward because so much carbon is concentrated in power plant emissions. But some geoengineering pioneers want to capture carbon directly from the air around us. This is much harder. The carbon dioxide in power plant emissions can be as much as 700 ppm, whereas in plain old air, carbon levels are about 400 ppm. That makes finding the carbon dioxide among the millions of other gas molecules in the air (including oxygen, nitrogen, and methane) far more difficult.

A revolutionary process called direct carbon capture (DCC) can rise to the challenge. A DCC company called Global Thermostat, founded in 2010, has built a prototype carbon capture system that pulls carbon dioxide out of the air anywhere outside. The system consists of 10-foot-wide (3 m) platforms—called contactors—that sit on top of a 40-foot-high (12 m) tower. The tower can be raised and lowered as needed. Up in the air, giant fans inside the tower suck masses of air across the contactors. Chemicals in the contactors then pull carbon dioxide in the air. The collected carbon dioxide is compressed and then sent by pipes to a permanent storage site or to industries that use carbon dioxide in manufacturing.

Between 2008 and 2013, a test facility in Ketzin, Germany, accepted more than 67,000 tons (61,000 metric tons) of carbon dioxide for storage in underground units. A German research organization operated the facility to explore the viability of carbon capture and sequestration.

Existing DCC systems capture about 40,000 tons (36,287 metric tons) of carbon dioxide every year. That’s only about 0.01 percent of the carbon dioxide produced worldwide. We’d need thousands of DCC systems to make even a small dent in the reduction of carbon emissions. But Dr. Peter Eisenberger of Global Thermostat is optimistic about the future of DDC. He has contacted industries that rely on carbon dioxide, such as soft-drink companies, oil companies, and greenhouses. Eisenberger thinks that by selling the carbon dioxide to these businesses, he can make DCC profitable, scale up the business to include thousands of carbon-capture machines, and help fight climate change.

In the future, Global Thermostat and other carbon capture businesses might have even more buyers for the carbon they collect. The Houston-based power company NRG Energy announced in 2015 that it would offer a $20 million prize to teams of engineers who can devise systems for turning carbon captured from coal- and gas-burning power plants into useful products. Forty-seven teams are vying for the award, which is called the Carbon XPrize. What kind of products might be made from captured carbon? Ideas include plastics, baking soda, vehicle fuels, cement, and foam for sneakers, couch cushions, and automobile seats. NRG explains that the carbon-based products will store carbon just like trees, oceans, and soil do, thereby keeping it out of the atmosphere. The company will choose the winning team in 2020.

Pros and Cons

Carbon removal systems have both benefits and drawbacks. Reforestation has important benefits for the environment because it restores forest ecosystems. On the negative side, reforestation is expensive and can take a long time to show results. Creating networks for capturing, transporting, and storing carbon also takes time and money. It requires building carbon-capture facilities, carbon-storage sites, and pipes to carry the carbon there. All this construction could harm the environment, since it likely would involve machinery and vehicles that run on fossil fuels and might require cutting down trees and thus destroying plant and animal habitats. An alternative to building extensive carbon pipelines would be to build carbon-capture plants next to carbon storage sites. This construction would also be quite costly, but it would save on piping and transportation costs. Most engineers think that underground storage sites make the most sense for captured carbon, since they don’t take up space aboveground, freeing up the land for other uses. But constructing such storage units would still disrupt natural environments and perhaps aquifers (underground water reservoirs).

Removing carbon from the atmosphere has negatives, including a high cost. But government and business leaders must weigh those negatives against the big positive: that removing carbon might perhaps save Earth from unlivable high temperatures.