For many years now, most cycling enthusiasts have attributed the first bicycle design to Leonardo da Vinci, one of the original Renaissance men, at around 1500 CE. Sketches in his Codex Atlanticus show a remarkably modern, two-wheeled machine; the only problem with this picture (so to speak) is that the sketches now appear to be a forgery. A few holdouts like historian Augusto Marinoni still claim Leonardo as the inventor of the bicycle, but whatever the truth of that original design may be, the first modern designs appeared in France and Germany around the 1860s (although there’s still a lot of debate about who exactly “invented” the modern machine that we ride today).

Since then, the bike has become a part of everyday life for people around the world. Bikes themselves have evolved into everything from superlight racing machines to utilitarian work vehicles. And that’s really the fun of it—because there are so many ways to enjoy cycling today, it appeals to just about everybody.

EUROPEAN RACES AND TWO WORLD WARS

During the 1880s, bicycle design still had a ways to go. Called a vélocipède (or “fast foot”), it had a wooden seat and rims, and some models couldn’t even be steered. These bikes lacked pedals, too, so riders just kicked their feet along and held on for the ride. One of these early models was called a “boneshaker” or a “penny farthing.” You’ve probably seen it before—it was the strange-looking contraption with a huge wheel in front and a tiny one in back, with a saddle (seat) placed perilously high in between them. Any guesses why they called it a boneshaker? Ouch!

The boneshakers incorporated pedals into the design, but the pedals were attached directly to the front wheel, much like a little kid’s tricycle today. Simple, sure, but it was a primitive design, which overemphasized the front wheel, leaving the ride unstable and dangerous. Riders coined the term “breakneck speed” to describe the results of a high-speed crash on one of these things.

By 1885, the “safety bicycle” had replaced the boneshaker. The safety bike looked a lot like what you and I ride today: two wheels of equal size, a saddle perched above the pedals, and handlebars for steering. They were quite a bit easier to ride than the wobbly boneshakers, so folks called them safety bicycles.

It didn’t take long for people to start racing one another with their new machinery. The first cycling race probably took place in Europe around 1860, although whether it was the French, Belgians, British, or Germans who hosted the event remains a point of much debate. Wherever it was that the first races took place, they were terribly difficult: The first edition of the Paris to Rouen road race covered 123 kilometers (about seventy-five miles), and the winner arrived after ten hours of “racing”! Modern competitors today might spend two-and-a-half hours on the same course, leaving them time to finish, take a hot bath, have dinner, and catch a nap before their hard-working ancestors would have finished.

These days we take it for granted that women should be able to compete in sports like soccer, basketball, and, yes, cycling. Sadly, however, women were excluded from the early years of bike racing. The earliest events generally didn’t include minority groups either, but all this would change as the sport evolved and the modern bicycle became an integral part of life in Europe and the United States.

By 1900, the bike had become an easy, cheap, and reliable transportation option for people all over the world. Bicyclists swarmed the streets of London, Paris, and New York. Racing had become quite a spectator sport, too, with the first edition of the Tour de France gathering great acclaim throughout France in 1903.

Even modern armies adopted the bicycle as a new technology. Soldiers in both World Wars pedaled throughout the battlefields with rifles clipped to their sides and bullets whizzing by. (Imagine that the next time you’re late for school and pedaling like mad!)

GROWING PAINS

Bike racing had caught on in the United States, too, with world champions competing in velodrome (track) races at Madison Square Garden and in cities like Denver and Chicago. Many newly arrived European immigrants were familiar with the sport, creating a captive audience. The sport grew in popularity in the late nineteenth and early twentieth century, attracting participants from outside immigrant populations.

Most famous among those was a young black man from Indiana named Marshall “Major” Taylor, who became world champion in the one-mile race in 1899 and 1900, making him the second African American at the time to win a world championship in any sport (boxer George Dixon beat him to the punch, winning the bantamweight world championship in 1890).

Taylor earned the nickname “Major” after performing bike tricks in a US military uniform, though he never served in the US military. He found quick success racing on the track, too. He was eventually banned by bigoted race promoters, but found a new racing home in Europe. At one point in 1898, he held seven world records in a variety of distances from the quarter mile to the two-mile event, and the velodrome in Indianapolis still bears his name to this day.

Renowned for his gentlemanly nature as well as his fast legs, Major Taylor became one of the first African American heroes in American sports.

Taylor and his fellow riders raced in front of raucous crowds throughout the United States. As the sport grew, small towns like Somerville, New Jersey, hosted bicycle races of all distances and types. In fact, the Tour of Somerville is the oldest continuously held race in the country, and they’ve been putting on the event since 1940.

By the 1950s, Americans’ sporting tastes had drifted away from cycling and moved toward team sports like baseball, football, and basketball. During the booming economic years after World War II, gasoline was inexpensive and people had the means to buy cars. The bike faded into the background, both as a popular sport and as a practical transportation tool.

THE BIKE MOUNTS A COMEBACK!

An adventurous group of Americans turned the trend around in the 1970s by developing the modern “mountain bike.” Military cyclists had tinkered with bikes adapting them to off-road riding, as had a group of French riders in the 1950s, but none of these trends lasted. It took the ingenuity and passion of some Northern California cyclists and innovators to make the idea stick.

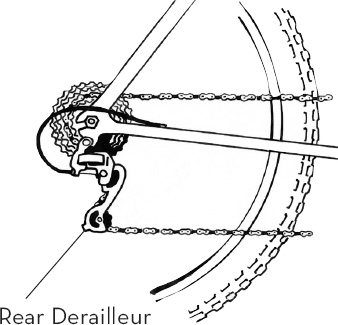

During the 1970s, visionaries like Charlie Cunningham, Joe Breeze, Tom Ritchey, and Charlie Kelly took “balloon-tire” bikes, similar to today’s “beach cruisers,” and outfitted them with derailleurs (the little gadget mounted by the rear wheel that helps change gears). Derailleurs and multiple gears offered easier pedaling uphill, opening new terrain to cyclists. Using fat tires and flat handlebars (instead of curved “road” bars), cyclists began tackling the rolling, forested terrain of Marin County, just north of San Francisco.

It didn’t take long before that same group started racing. On the flanks of Mount Tamalpais, the riders competed in a downhill race known as the “Repack.” (After a run, the bikes’ drum brakes—an older brake design housed inside a drum or cylinder—would be so fried that they would need to be repacked with grease—hence the name; the trail the race was run on is known by the same name, and riders still flock to it to this day.) Meanwhile, halfway across the United States, another gang had begun riding over Pearl Pass, from Crested Butte to Aspen, in Colorado.

It didn’t take long before that same group started racing. On the flanks of Mount Tamalpais, the riders competed in a downhill race known as the “Repack.” (After a run, the bikes’ drum brakes—an older brake design housed inside a drum or cylinder—would be so fried that they would need to be repacked with grease—hence the name; the trail the race was run on is known by the same name, and riders still flock to it to this day.) Meanwhile, halfway across the United States, another gang had begun riding over Pearl Pass, from Crested Butte to Aspen, in Colorado.

Mountain biking opened up endless miles of off-road terrain. People who loved to hike, backpack, and enjoy nature suddenly had another way to enjoy the outdoors. They could cover twenty miles or more in a day, instead of just a few. Anywhere there was a dirt road or trail, they could ride a bike.

And by this time, cycling wasn’t just for men. Jacquie Phelan was an early female cycling pioneer, racing with the guys (and beating plenty of them, too!). She went on to found a counterculture club of free-thinking female riders known as the Women’s Mountain Bike and Tea Society (WOMBATS) and represented the United States at the world cycling championships, becoming an icon within the sport. She and her male buddies kick-started the mountain-bike revolution we’re still enjoying today.

THE RED ZINGER, THE COORS CLASSIC, AND AMERICAN RACING

In the early 1980s, American cycling received another boost when an enthusiastic kid from Reno, Nevada, took the road scene by storm. Greg LeMond won the junior World Championships in 1979, took silver in the men’s World Championships in ’82, and finally won it in ’83, becoming the first American to do so.

The women weren’t far behind. Though many mistakenly believe LeMond to be the first American winner of the Tour de France, it was actually Marianne Martin, a native of Fenton, Michigan. She won the women’s Tour in 1984. That same summer, Americans Connie Carpenter Phinney and Rebecca Twigg won the Olympic gold and silver medals respectively in road cycling. By the mid-’80s, American women were at the top of the sport.

The American men did their best to keep pace. LeMond won the Tour de France in 1986, alongside his teammate and fellow American Andy Hampsten, who won “Best Young Rider” from the race organizers. LeMond’s story became even more incredible when he narrowly survived a hunting accident in 1987 (his brother-in-law wounded him with a shotgun!), only to return to cycling to win the Tour twice more, in ’89 and ’90, and another world championship.

The Stage Race: A Race with a Bunch of Races Within It

“Stage races” are days, or even, in the case of the Tour de France, weeks long. Each day, there are two races going on—one for that individual day’s “stage” win, and another for the overall prize (usually earned by having the lowest overall time) at the end. The rider who performs the best, day in and day out, wins the overall, while each day’s winner is celebrated, but she or he might eventually finish far down on the overall standings.

For example, if on day one, riders climb an enormous mountain, and one finishes three hours behind the competition, he could win all the remaining stages (and be celebrated each and every day he wins!), but unless he makes up those three hours that he lost, he won’t win the overall. Riders victorious in a three-week race like the “Tour” do everything well and can’t afford to have a bad day.

Cycling’s popularity boomed. Rising gasoline prices pushed some to return to the bike for transportation. The United States finally had a world-class bike race, too: Sponsored by the Celestial Seasonings tea company from 1975 to 1979, it was known as the “Red Zinger” (one of the company’s most popular flavors). In 1980, the Coors Brewing Company threw its support behind the race and built the “Coors Classic” into an international sensation, attracting world champions and crowds numbering in the hundreds of thousands.

The Coors Classic changed its course for each edition of the race, and in 1988, its final year, riders started in Hawaii and concluded in Colorado. After competing in Hawaii, the entire race—staff, riders, and all the equipment—hopped on airplanes and flew to California, where they recommenced the race. Davis Phinney, the first American man to win an individual stage of the Tour de France, won the overall race, which finished in his hometown of Boulder. And incidentally, Phinney’s son (with wife and Olympic champion Connie Carpenter Phinney), Taylor, has already won a world championship on the bike, as a junior rider in 2007. And in 2008 and 2012, he represented the United States in the Olympics. Good genes!

LEMOND STARTED THE JOB ARMSTRONG FINISHED

The Coors Classic popularized cycling, especially in Colorado, becoming the state’s own Super Bowl. Greg LeMond, Andy Hampsten, Connie Carpenter Phinney, and Inga Thompson became household names to those who grew up near the race. However, while cycling may have been growing in popularity in Colorado, it was still a backwater sport to most of the United States.

Meanwhile, a fiery kid from Texas made headlines in the late ’80s as a triathlete. Lance Armstrong won the “Iron Kids” triathlon at thirteen. By the age of eighteen, he’d won a national triathlon championship, competing as a professional. Olympic cycling coaches convinced him to try out for the cycling team, and he spent his senior year of high school at the Olympic Training Center in Colorado Springs. He made the national cycling team and raced at the junior world championships in Russia in 1989. (Dede Barry, author of the foreword to this book, won the junior women’s race that year—not a bad team for the Americans.)

Armstrong quickly became one of the best road-cycling pros in the United States. He competed at the Barcelona Olympics in 1992, finishing fourteenth. He moved to a European-based team at the end of that season, and then won the world professional championships in 1993 in Oslo, Norway. By 1996, he was the top-ranked pro in the world—but Lance and cycling still hadn’t earned widespread fame in the United States

Cancer, Seven Tours, and Bikes Galore

After experiencing pain and fatigue on the bike, Armstrong discovered in October of 1996 that he had testicular cancer. Doctors gave him less than a 50-50 chance of living, as the cancer had spread to his lungs and brain. It didn’t sound hopeful. The cycling world was stunned.

Surgery and aggressive chemotherapy improved his prognosis. He recovered steadily and soon his thoughts returned to racing. By the fall of 1998, he had rebuilt himself into an even better cyclist. He placed fourth at the world championships and fourth at the three-week Vuelta a España (or Tour of Spain—that country’s version of the Tour de France). Those who were shocked by the illness were even more astounded by his return. He’d beaten cancer at unbelievable odds.

Armstrong returned to the Tour de France in 1999. He’d already defied doctors’ expectations by racing again. The ’99 Tour transformed him into one of the world’s most inspirational figures, particularly to cancer patients and survivors. He began the race with most fans hoping for great things, but no one expecting a victory. He not only won the race, but he also went on to victory in the following six Tours de France, breaking the previous record of five victories in the race.

With Armstrong’s return to success, though, came persistent accusations of doping—the illicit use of performance-enhancing drugs (PED’s) to gain an advantage on his rivals. Armstrong and his entourage vehemently denied the charges, pointing to hundreds of negative tests, which seemed to bolster their claims. Controversy dogged the remainder of his career, but for the most part the public believed armstrong and his celebrity only grew.

Lance Armstrong raced during a period of rampant cheating in professional cycling (not to mention other sports). If that were his only transgression, it would be relatively easy to forgive. Many, many cyclists, including good friends of mine, chose to take PED’s. I understand the compromise—so many others were doing it, winning big races in Europe was nearly impossible without doping.

More unforgivable in hindsight is Armstrong’s intimidation, bullying, and harassment of his detractors. He spent untold sums of money and much personal energy attempting to silence people who we now know were speaking the truth. Journalists like David Walsh of the Sunday Times of London, former team staffers like Emma O’Reilly, and other cyclists like Greg LeMond were sued, their professional and personal lives upended, and their reputations tarnished by Armstrong and his team of lawyers, his agent, and a few of his sponsors.

At the time of this writing, it seems Armstrong’s real troubles are just beginning. There’s talk of several multimillion-dollar sponsors seeking return of their money, he’s no longer officially associated with the LAF, and it remains to be seen how history will judge him.

Armstrong was a courageous, tenacious Tour rider. Most important, he fought a brave and successful battle against cancer, inspiring millions in the process. To have those traits overshadowed by his lying and cheating is both understandable and sad.

From the early 2000s on, Armstrong was the most famous sports personality on the planet, better known than Tiger Woods, Michael Jordan, or Cristiano Ronaldo. For good reason—he’d not only overcome advanced testicular cancer, but he’d also returned to one of the most difficult sports events in the world—and won it! Armstrong’s victories kept him in the news, as did his off-the-bike efforts. He founded the Lance Armstrong Foundation (LAF)—known for its yellow “Livestrong” bracelets—shortly after his own diagnosis in 1996 and began raising tens of millions of dollars for cancer research, patient support, and education.

Armstrong’s fame drew more and more people to the sport. As these people took to riding, word quickly spread that it is a fun and safe way to stay in shape, not to mention a great way to rehabilitate injuries or recuperate from certain orthopedic surgeries. In short, Armstrong’s career introduced many Americans to the wide world of cycling.

By the time of his final retirement, in early 2011, the mounting accusations of doping had intensified. First, a federal grand-jury investigation (later closed) and then scrutiny from the United States Anti-Doping Agency (USADA) turned the rumors into official charges. After the majority of Armstrong’s former teammates testified that they—and Armstrong—had used PED’s, in January of 2013, Armstrong finally admitted to doping throughout most of his career. His public image was destroyed and the naysayers were finally vindicated. Tests or no tests, Armstrong had lied and cheated during every one of his seven Tour de France victories. His wins were erased from the record books and officially speaking, he’s no longer a Tour champion.

CYCLING TODAY

Cycling businesses sell almost twice the number of bikes today that they did in 1981, although the population of the US as a whole has only grown by about a third. The quality and durability of bikes has improved tremendously over the past decade, too. Materials like carbon fiber have made them lighter and stronger than ever. In fact, for $1,200 a well-heeled bike enthusiast can buy a road bike that’s actually better than what guys were riding in the Tour de France only fifteen years ago.

Cities, counties, and the federal government are supporting more cycling projects, too, helping to make bike commuting a more popular mode of transportation. As gas prices rise and more people recognize the impacts of climate change, hopefully we’ll see people riding bikes for shorter trips and saving their cars only for essential outings.

Technology has also made the sport more fun. Several smartphone apps can track your cycling as you pedal. With them, you can compare your rides against buddies in town, or even keep track of friends riding in other states.

More sophisticated computers and “power meters”—gizmos that measure how many watts you generate when pedaling—now let you keep track of all your training and mileage. And some cycle computers can calculate how much CO2 (carbon dioxide, the stuff causing global climate change) a rider spares the atmosphere by riding his or her bike instead of driving.

SO…

Biking’s come a long way since the boneshaker first hit the scene at the turn of the century! In fact, at this point, the biking “scene” has split up into a diverse array of earth-conscious commuters, fitness advocates, hard-core racers, and just casual groups of tourists and vacationers. So whether you want to conquer the world, save the earth, or just get in shape again, there’s a bike—and a biking community—already waiting for you.

Biking’s come a long way since the boneshaker first hit the scene at the turn of the century! In fact, at this point, the biking “scene” has split up into a diverse array of earth-conscious commuters, fitness advocates, hard-core racers, and just casual groups of tourists and vacationers. So whether you want to conquer the world, save the earth, or just get in shape again, there’s a bike—and a biking community—already waiting for you.