A dventure cycling ranges from year-long, ’round-the-world journeys to single-night stays in hotels just a few miles from home. You get to decide just how deep down the rabbit hole you want to ride. The bike opens doors you might otherwise roll right by. You’ll meet friends, discover things about yourself, laugh lots, suffer some, and if you’re inspired to hit the open road, you’ll see places, people, and landscapes wilder than you can believe. Touring—or adventure cycling—is your on-ramp to some amazing new experiences.

A few words of caution: For any bike trip longer than a few hours—and certainly any time you’re spending a two-wheeled night away from home—planning is critical. Thorough planning will make you more comfortable, reduce your stress, and greatly increase your chances of returning with a happy story (instead of a horror story).

Adventure cycling also requires sharp route-finding skills and sound judgment, so you might want to have someone more experienced come along for your first few outings. Eventually you’ll be ready for a trip with just your friends, or even a solo mission, but don’t bite off more than you can chew just yet.

If you sleep in a nice warm bed every night, why hit the open road with your bike, sleeping in campgrounds or cheap motels? Answer: It’s fun! It’s a little bit intimidating, totally interesting, and usually exciting when you open the map, plot a course, and start pedaling, knowing you won’t be coming home until—tomorrow, next week, or next year.

You’ll be amazed, too, at how people approach you when you’re on your bike. In a car with out-of-state plates, you might be looked at suspiciously or ignored altogether. On a bike, locals will walk right up to you and start chatting. Talk to veterans of the adventure cycling circuit, and they’ll tell you stories of being offered hot meals and places to stay, and many keep in touch with folks they’ve met along their routes.

Sure, some people don’t find the idea of adventure cycling any more appealing than backpacking or doing the hostel circuit in Europe, but if you do, now’s the time to start exploring the big, wide world out there.

THE RIGHT BIKE FOR THE JOURNEY

You can tour on just about any kind of bike, but usually a road or mountain bike is the best call. Adventure cycling requires lower (easier) gears than you’ll be used to, but keep in mind you might have an additional five, ten, or thirty pounds of stuff with you, so the hills will seem even tougher than usual. Traditional mountain bike gearing works well, but easier rear cogs on a road or cyclo-cross bike will keep you moving when you’re laden with extra tonnage.

A dedicated touring bike is a luxury, and if you really get the bug you might want to think about one down the road. For now, though, any comfortable bike with twenty-six-inch or 700c wheels (typical mountain and road wheels, respectively) will probably work.

HAVE CREDIT CARD, WILL TRAVEL

The simplest form of adventure cycling is “credit-card touring.” You decide on a location, plot a safe and scenic route to it, bring along the bare minimum in terms of gear, pack your (or your parents’) credit card, and start pedaling. Having a card along means you can stop for food at restaurants, supermarkets, and convenience stores, and once you arrive at your destination, you can check into a hotel for the night.

If you’ve never used a card before, double-check with your parents and the company issuing the card that you can charge with it while away. Your folks can call their card’s customer service department and let them know you’ll be using it, so if a hotel or restaurant gives you problems, have them call the card company, which can then authorize the charge. Bring your ID, be polite, and you shouldn’t have too much difficulty.

The Hardest Race of All

The Race Across America, or RAAM as cyclists know it, is about as simple as it gets: See who can race from the West Coast of the continental US to the East. Sure, there’s a prescribed course, but beyond that, riders can sleep as little or as much as they want, stop for food or massages however often they see fit—whatever it takes to get to the finish.

Pete Penseyres set the record in 1986, crossing from Los Angeles to Atlantic City in eight days, nine hours, and forty-seven minutes. He slept as little as ninety minutes a night and derived 80 percent of his calories from liquid protein shakes. Riders typically enlist a large support staff, helping to feed them and drive alongside in a “SAG wagon” (see below) with spare clothing, extra wheels, and plenty of food!

Part race and part epic tour, RAAM is one of the world’s hardest athletic endeavors.

YOUR GUARDIAN ANGEL: THE SAG WAGON

If you’re looking for a little more support along the way, and perhaps a bit more adventure, then consider the SAG wagon, otherwise known as any sort of car, van, or truck that can follow along and carry your stuff. Depending upon whom you ask, SAG either stands for “Support and Gear,” or it just refers to the way the vehicle “sags” behind you and your cycling buddies as you tick off the miles. Its meaning becomes less important when you seek refuge from the the searing heat or thunderstorms, feast on fresh fruit and chocolate bars, or change into clean cycling clothing, going from fatigued to psyched in two minutes flat.

The SAG wagon follows your tour, carrying spare gear, rain jackets, water, food, and camping gear, if you’re planning on sleeping out. This liberates you from stopping in “civilized” spots for food and rest. Sometimes a group of cyclists takes turns with the driving/support duties: One rider will drive for the morning, while her buddies ride, and then she swaps out for the afternoon leg and another rider drives until dark. There are also organized tours on which the company provides SAG wagons for a few or a few dozen cyclists. It’s a great way to tour, with a built-in safety net.

An SUV or minivan works great as a SAG vehicle. If you go with an organized tour, they’ll have food, maps, and equipment all ready for you. Hit the web and check the end of this chapter for leads on finding a touring company if you go that route. If you’re throwing together your own journey, you’ll need to arrange your own food, maps, and camping equipment.

Get to Know: The ACA

A bike-crazed posse in Missoula, Montana, runs the Adventure Cycling Association (AdventureCycling.org), and I think they’re on to something. Since 1973, they’ve helped people get on their bikes, pack light, plan well, and go big. When you think about it, planning your own bike trip is more being adventurous than being a tourist, so I use their term, adventure cycling, instead of bike touring. Makes more sense to me. Visit their site if you need help with maps, equipment, random questions, or just about any issue related to leaving home with your bike. If they don’t have the answer, they’ll connect you with someone who does.

Their “Pedal Pioneers” page is set up to help parents plan for cycling with kids, but give it a read as it will give you a few ideas, too.

STEPPING OUT ON YOUR OWN

After a few supported or organized tours, you might be ready to go it alone or in a small group. This requires meticulous planning so you don’t end up at the campground at night with everyone wondering why no one brought the stove and what happened to the tent. Fully independent adventure cycling is the most committing style, and it’s not for everybody.

THE ALL-IMPORTANT GEAR LIST

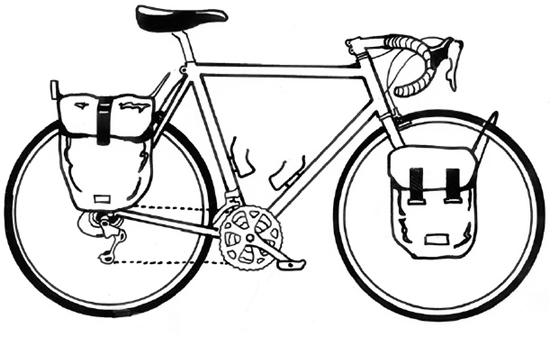

If a more independent tour sounds fun, you’ll need a system for carrying your gear. This comes down to panniers or a trailer. Remember that panniers are essentially saddlebags for your bike, while a trailer rolls along behind you with all your gear tucked inside a waterproof cover. Both systems have their benefits and cyclists have gone around the world using each. Keep in mind that panniers require racks and a way to fasten them to your bike. A good shop can help you set this up, but it’s another consideration to keep in mind.

With any tour, but self-supported ones in particular, your gear list is critical to staying comfortable and safe. You’ll need to carefully plan:

Your sleep system, including a tent

Your sleep system, including a tent

Your food and drink, which is to say lots of both—and make it nutritious, too

Your food and drink, which is to say lots of both—and make it nutritious, too

Spare parts for repairs

Spare parts for repairs

Special parts like fatter tires for dirt roads and a smoother ride

Special parts like fatter tires for dirt roads and a smoother ride

Your clothing, including rain gear or a sun hat for under your helmet

Your clothing, including rain gear or a sun hat for under your helmet

Maps with your route, places to refuel, bike shops, and campgrounds marked

Maps with your route, places to refuel, bike shops, and campgrounds marked

Your safety equipment, like front and rear lights and an orange visibility flag

Your safety equipment, like front and rear lights and an orange visibility flag

Cash, credit cards, a cell phone, and something to read at night

Cash, credit cards, a cell phone, and something to read at night

This is just for starters. Your gear list will have to take into account the weather you might experience, the time of year and probable temperatures, and the kind of riding you’ll do—rough roads, big climbs, and possible hazards. Connecting with other cyclists online can help you fine-tune your list, as will some reading on AdventureCycling.org. Do your research, and your trip will run that much more smoothly.

SHIPPING YOUR BIKE

Traveling by train, air, or bus with a bike can be a hassle, no doubt. Bikes can break down and bikes and gear can get stolen, but it’s generally worth the risk for the right trip. Let’s review options. Numerous companies and services will ship your bike. Some adventurers mail their bike to and from their touring location. It’s expensive, but it does save you some hassle and travel planning.

If you pack it yourself, you can ship via UPS or FedEx, or with a service like BikeFlights or Sports Express. Using these services to ship within the US is not unreasonably pricey, but as soon as you start shipping to Europe or beyond, expect to pay hundreds. Make sure your bike is insured on your parents’ homeowners policy or with your renters insurance if you’re living on your own. Some travel insurance policies will cover your ride, too—double-check the fine print because they sometimes have an exclusion for expensive computers, bikes, cameras, and the like.

Pedal Your Way to School Credit

Have you considered the possibility of getting some school credit for your efforts in cycling? Here’s a great opportunity to do it: Organize a senior cycling trip, with an educational or service-oriented theme. How about riding a bunch of bikes up to the Sioux reservation in South Dakota? You can donate your bikes to interested teens on the res when you leave for home. You could also ride to other schools, talking about the environmental benefits of cycling as transportation. Find a friend who’s interested in the project and dream something up.

Drop by Sprockids.com—it features a ton of information to get you rolling toward school credit and beyond.

BOXES

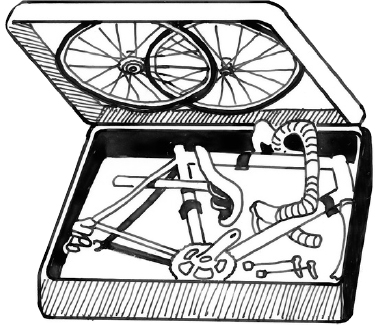

Any time you slap a mailing label on your bike, you’re going to have to pack it, which means disassembling it and organizing it within a box or case. You can buy a plastic case for $199, and it’ll do a great job of protecting your bike. Several manufacturers have models that are easy to use and really durable. These are great for shipping, and can also be checked as luggage on flights. Rates for flying with a bike vary; check before you book a ticket because some airlines charge as much as $200 each way, while others are free. What looks like a cheap ticket might be quite a bit more, once you pay a bike fee.

If your shop will help or if you’re pretty crafty, you can fashion your own box. See if your shop has a cardboard box in which a new bike has just arrived. You can fit your disassembled bike into it, using cut sheets of cardboard to reinforce areas around the derailleurs. This takes a little trial and error, so see if an experienced mechanic will help. Bring him or her some treats for the effort (you can never go wrong with cookies—the universal currency).

For help on disassembling (and reassembling!) your bike, check online for video tutorials or pay your favorite mechanic a few bucks to show you how the first time. You can video him or her doing it, so you’ll know how to do it yourself. And remember your tools when you travel—you’ll need, at minimum, Allen wrenches, a basic multi-tool, and any specialized items for your particular bike.

A POINT-TO-POINT TOUR

Big bike trips sometimes mean landing in one city and departing from another. Instead of a loop, you’re going “point-to-point.” In this case, you’ll need to assemble your bike and ditch the box it traveled in, so a homemade cardboard job is the best call in this instance. Once you complete your tour and you’re ready to head home, you’ll need to locate and build another box.

Sounds tricky, but with some friendly, enthusiastic emailing, you’ll be surprised what a bike shop in Dublin or Dubai or Durban might do for you. You can also check adventure cycling forums online and post your travel itinerary. Other riders might know a shop or hotel in your departure city that’d be willing to help. Just repay the favor someday, to the folks who helped you or another intrepid traveler you encounter on the road. Bike karma—a powerful force in the universe!

How to Beat the Airlines at Their Own Game— “Breakaway” Bikes

“Breakaway” bikes, or bikes that split in two for travel, have become more popular in the past few years. Two companies, Ritchey and S and S, make coupler systems that are built into a bike’s frame, allowing you to split the frame and pack it in a box about eighteen inches deep and as big around as a road wheel. Under current regulations, no airlines charge for a box this size, saving you hundreds in excess luggage fees. Saved cash means way more money for gelato while touring in Italy.

TRAINING?! NOBODY SAID ANYTHING ABOUT TRAINING!

Don’t freak out, I’m not talking about 6 a.m. runs and eating raw eggs. But, I do want you to have a blast when you head out touring, so let’s make sure you’re ready.

The most important thing for a few days of adventure cycling is being comfortable. If you do all the planning in the world, have fantastic weather, and set up a great bike, but then find yourself miserably tired or uncomfortable by the first night—game over. By putting in enough training time beforehand, you should be able to get your body ready for the trip ahead.

Make sure your bike fit falls within the ballpark for saddle height and handlebar position. Let’s assume you’re set as far as those details go.

The next hurdle in staying comfortable is spending enough time in the saddle that your butt, knees, back, hands, and neck are used to it. Going from no cycling at all to six hours a day is going to stress your body, and you’ll end up aching, so if you’re planning a really big tour, try to make sure you’re riding plenty in the months leading up to your trip.

If you’ve never ridden for a week straight, perhaps a shorter tour—or scheduling a couple of rest days along the way—is in order. If you’re going for the long haul, just increase your mileage in the weeks coming up to your tour. Don’t increase it by more than 10 percent a week and your body will have time to adapt and strengthen. Two weeks before your trip, taper off your riding to give yourself time to recover.

TRICKS OF THE TRADE

Bike Forums

Since we’re talking about forums, note that many cycling sites these days have reader forums for advice, debating trailers versus panniers, posting trip reports, or anything to do with two wheels. Take advantage of them. There are always enthusiastic, helpful people willing to help you avoid mistakes they’ve already made.

Check out www.BikePacking.net, www.BicycleTouring101.com, and the Adventure Cycling Association site to get started.

STRETCH, BREATHE, AND SMELL THE ROSES

Any time you’re out pedaling, whether it’s on a trip or not, don’t hesitate to take rest breaks. If you’re feeling a little tight in your hamstrings, back, or neck, then stretch for a few minutes, enjoy the view, and relax. Racers out training almost never stop, except to fill bottles. Reformed racers (read: me!) and people riding for fun stop all the time—for coffee breaks, for cookies (recognize a theme here?), to snap photos, to put on sun-screen, or even for a swimming hole. It’s a way mellower trip, and it gives the body a little break from the bike.

PROTECT THAT BIKE!

Whatever you do, don’t get your bike or your gear stolen. Easier said than done, sure, but a few precautions will help.

First off, try never to lock or leave your bike where you can’t see it. If you’re going into a restaurant or a supermarket, lock it outside of a window. Hopefully you’ll be able to watch it while inside, but even if you can’t, a would-be thief will be in plain view of somebody inside, and hopefully he or she will think twice about snatching your ride.

For bike tours, big groups usually bring a thin, metal cable for extended stops. When the whole group pulls over for lunch, ride leaders loop the cable through all the bikes and lock it to a fence or lamp post. While a thief could cut the cable pretty easily, at the very least it prevents somebody from just hopping on a bike and pedaling away. When touring, a cable also allows you to lock your trailer or panniers.

If you have a SAG wagon, then don’t skimp on locks— bring a traditional “U” lock, as well as a cable. You can also bring a “cable lock,” which is just a steel cable that also has a combination lock built into it. It’s actually great to have both—that way you can lock up the frame, wheels, and racks.

If you’re going self-supported, then weight becomes an issue. The small “U” locks that messengers use are probably the safest, but they won’t let you secure your wheels and other equipment. A short section of steel cable is probably worth the extra ounces because of the extra security it provides.

Safer Still: Getting Your Bike Out of Sight

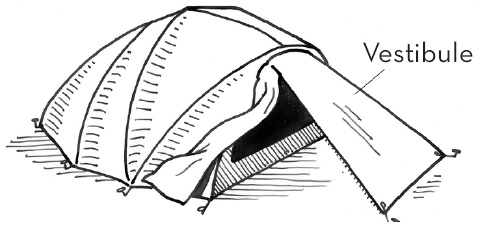

Some cyclists also take along a tent with a “vestibule.” A vestibule is a covered entry area: Backpackers leave shoes and wet gear in it, but as a cyclist you can roll your bike into it. Zipping the vestibule shut isn’t like locking your bike, but it does get it out of sight and makes it more of a hassle for a thief to get at it. It’ll cost you an extra pound or two, and a few bucks, but it’s worth it.

You can also ask at campgrounds, restaurants, and parks about storage rooms or fenced areas that you can lock your bike in. Again, anything that puts another layer of hassle and security between you and the thieves is a good idea.

Keep Copies of the Important Stuff

Finally, anytime you leave your bike and gear, always have your ID, cash, credit cards, airline tickets, and passport with you. Having a photocopy of these stashed in your gear is a good idea, too, just in case you lose something or get mugged. This way you’ll have all your relevant numbers and information with you, so you can cancel cards and get a passport reissued. I’ve taken to saving copies of my airline tickets, passport, and health insurance info online that way I can access it anywhere there’s a computer.

Finding Your Adventure Inspiration

These writers, and one filmmaker, share some of the coolest bike trips imaginable, so check them out:

The Masked Rider: Cycling in West Africa, by Neil Peart. Peart is the drummer from the band “Rush,” and it’s cool to read about a rock star living cheap and riding around Africa.

Mud, Sweat, and Gears: A Rowdy Family Adventure Across Canada on Seven Wheels, by Joe “Metal Cowboy” Kurmaskie. Joe somehow figures out how to do an amazing bike journey with his whole family, including kids under ten!

Hey Mom, Can I Ride My Bike Across America?: Five Kids Meet Their Country, by John S. Boettner. Young kids going for it, riding across the United States.

I Made It: Goran Kropp’s Incredible Journey to the Top of the World. This film documents Kropp riding from Sweden to Mount Everest, soloing it, and riding back. Epic.

Adventure Cycling: My Own Tour de France

By Bob Long

I took up cycling rather late, after retiring from my professional life as a lawyer, and was immediately drawn into the sport—first as just a way to stay fit, and then over time, as what a friend has termed “my organizing principle of life.”

As I worked hard at improving my performance on the bike, it soon became apparent that I was never going to be the speediest guy on the road, because of both my late start into cycling and my large-sized frame: I’m over six feet and built more like a football player than cycling star.

As Tour of Italy winner Andy Hampsten once told me when I asked him about training, “Bob, I don’t know how to break this to you, but I don’t think there is ever going to be a place for you in the Tour.”

But I wasn’t deterred. I loved to ride and gradually became faster and found that I had pretty strong endurance. I could go long distances, recover quickly, and do it over again. I worked my way into centuries (hundred-mile rides) and other long events and then started looking for other challenges. What immediately appealed to me was doing multi-day events covering significant mileage. Fortunately, my spouse, Susan, also began to get into cycling and found the prospect of doing long cycling trips appealing.

We started with a week-long tour through southern Oregon the first year and then a ten-day tour in eastern British Columbia the next. Both offered the challenge of riding seventy to eighty miles per day and climbing some significant hills and passes, and both provided miles of beautiful terrain and scenery. We soon concluded that there is no better way to see the countryside and absorb the local flavors and colors than from a bicycle.

I then began to set my sights on even longer rides and greater challenges. In short order, I did a thirty-five-day, 2,600-mile trip up the Continental Divide, from southern New Mexico to Jasper, Alberta, and then last summer, a fifty-day, 4,000-mile trip across North America, from the Olympic Peninsula, in Washington, to Bar Harbor, Maine. Both were lifetime experiences.

As I learned to ride long distances, I also gradually improved my climbing abilities and decided I wanted to do even tougher climbs on the bike. One summer, I toured three weeks around Colorado and climbed most of the best known passes in the Rockies, and I have also done the same thing in the Sierra and Cascades. Having handled those, I decided to undertake some of the famous passes in the Italian and French Alps, like the Stelvio, Passo Gavia, Mortirolo, Mont Ventoux, and Galibier. I am still not the speediest, but I get these climbs done steadily and strongly.

Andy Hampsten is right: There is never going to be a place for me in the Tour, but I have learned to ride the same distances and climb the same vertical as any Tour route provides, and I love doing it as much as any Tour rider out there. And as an added joy for me, so does Susan.