CHAPTER 8

Looking Forward: The Future of Big Data

Without Big Data, you are blind and deaf and in the middle of a freeway.

—Geoffrey Moore

For some time now, retail giant Target has taken data mining and Big Data very seriously. Forget the fact that most retailers have had to operate at relatively low margins. For instance, supermarkets historically have been volume businesses. They make profits of approximately three cents on the dollar.1 Adding salt to the wound, retailers like Best Buy, Walmart, and Target these days face an entirely new problem. Connected consumers are visiting traditional retail stores, looking at products, whipping out their smartphones, finding the same products online for lower prices at sites like Amazon.com, and ordering them right in the stores. This process has been termed showrooming2 and it represents a herculean challenge for big-box retailers, especially if the purchase takes place in a state in which Amazon need not pay sales tax. Best Buy management sees the writing on the wall. The company may soon go the way of Tower Records and Blockbuster Video.

Faced with few options, Best Buy announced on October 15, 2012 that it would match Amazon’s prices in its physical stores.3 Whether this will work is anyone’s guess, but competing against Amazon on the basis of price has historically been an exercise in futility. Amazon CEO Jeff Bezos understands the concept of a loss leader and has said repeatedly that he is comfortable operating at “very low margins.”22 (Forget low margins and think for a minute about negative margins. Amazon is rumored to have taken a $50/unit loss on the Kindle Fire. The company hopes to make the money back on movie, book, magazine, and music purchases. Some speculate that in the near future Amazon will give away the basic Kindle.)

But let’s stay on target with Target. In September 2012, the company fired back at the Seattle-based behemoth. Target announced that it was following the lead of Walmart and ceasing sales of Amazon Kindles in its physical stores.4 It turns out that independent bookstore owners and aficionados aren’t the only ones with axes to grind against Amazon. Target might be the proverbial Paul Bunyan.

In an ultra-competitive business landscape, what’s a retailer like Target to do? Funny you should ask. In the course of my daily activities and while researching this book, I came across some downright fascinating uses of Big Data. Without question, my favorite anecdote comes from Target.

PREDICTING PREGNANCY

In a February 2012 article for The New York Times titled “How Companies Learn Your Secrets,”5 Charles Duhigg writes about a statistician named Andrew Pole hired by Target in 2002. Soon after he started his new job, two employees in the marketing department asked Pole a strange question: “If we wanted to figure out if a customer is pregnant, even if she didn’t want us to know, can you do that?” Intrigued and up to the challenge, Pole said yes and began work on a “pregnancy-prediction model.” He looked at products that potentially pregnant women bought, like lotions and vitamins, as well as products that they didn’t buy. A woman four-months’ pregnant is probably not going to purchase baby food and diapers and store them for five months. (Duhigg’s lengthy expose is nothing short of riveting, and I highly recommend reading it.)

The marketing folks weren’t just hazing Pole or giving him busy work. They had a very real business reason for approaching him. Ultimately, they used Pole’s model to send custom coupons to women that Target believed to be pregnant—or, more accurately, women who were likely to be pregnant based upon Target’s data.

Don’t yawn yet. About a year later, the story gets really interesting. A man angrily walked into a Target outside Minneapolis, Minnesota. He demanded to see the manager. He was clutching a mailer that had been sent to his daughter. From Duhigg’s article:

“My daughter got this in the mail!” he said. “She’s still in high school, and you’re sending her coupons for baby clothes and cribs? Are you trying to encourage her to get pregnant?”6

It turns out that the manager didn’t know what the customer was talking about. (Retail employees are often unaware of corporate marketing efforts.) He took a look at the mailer. The father wasn’t lying; the mailer was in fact addressed to his daughter. It contained advertisements for maternity clothing, nursery furniture, and pictures of smiling babies. The manager promptly apologized to his customer. A few days later, he called the man at home to apologize again. On the phone, though, the father was somewhat humbled.

“I had a talk with my daughter,” he said. “It turns out there’s been some activities in my house I haven’t been completely aware of. She’s due in August. I owe you an apology.”

In a nutshell, Target knew that a teenage girl was pregnant before her own father did. Pole’s pregnancy prediction model did not require individual names, and Pole certainly did not know the identity of the woman in Duhigg’s story. None of that mattered. His model didn’t need that information. Target’s own internal sales data was plenty.

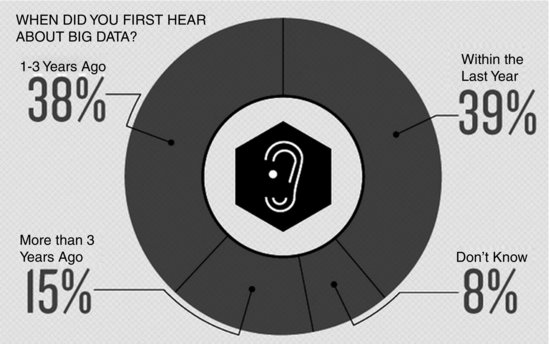

Target saw the Big Data revolution before many other retailers. Consider the infographic in Figure 8.1.

In other words, Target could predict if a seventeen-year-old girl was pregnant (while her own father didn’t know) way back in 2002. Imagine what the company could do today. The possibilities are limitless and, I’ll admit, even a little scary. Many of today’s Big Data sources, techniques, and tools weren’t around or nearly as advanced ten years ago as they are today.

BIG DATA IS HERE TO STAY

Duhigg’s Target article was nothing if not controversial. Just look at the 500-plus comments it generated. It’s hard to read it and not have a strong opinion about the ethics of Target’s data mining practices. Leaving that aside for a moment, stories like this illustrate the often-shocking power of Big Data—and more and more organizations are starting to take notice. Anecdotes like these are certainly compelling, but they represent just the beginning. More and more examples, case studies, journal articles, books, and innovative uses of Big Data are coming. And forget hyperbole from software vendors and consultancies that clearly have skin in the game. Quotes from recognized and more objective experts only add fuel to the Big Data fire. Joe Hellerstein, a computer scientist at the University of California in Berkeley, believes that we’re living in “the industrial revolution of data.”7 While it’s too early to say, we may look back at the 2012 presidential election as a watershed moment for Big Data—the point at which it crossed the chasm.

BIG DATA WILL EVOLVE

In his 2010 book Where Good Ideas Come From: The Natural History of Innovation, Stephen Johnson writes about inventors who ultimately were, quite frankly, too far ahead of their time. For instance, English mathematician, philosopher, and inventor Charles Babbage conceived of a machine that resembled the modern-day computer nearly more than a century before it could have remotely been considered commercially viable. Why such a long gap between Babbage’s master plan and the modern-day computer? According to Johnson, for ideas to take hold, they must fit into something he calls the adjacent possible. One can certainly innovate, but innovations must rely largely upon components and materials that currently exist—or soon will. Babbage’s concept of a computer could never work (in his lifetime, anyway) precisely because it was too advanced. That is, the majority of the parts necessary to turn his machine into a reality simply didn’t exist yet—and wouldn’t for decades.

And the adjacent possible is alive and well today. More recently, in February 2005, three former PayPal employees started a little site called YouTube. Think about the timing of YouTube for a moment. This happened ten years after Mosaic and Netscape brought the commercial web to the masses. Again, why the delay? In short, a site like YouTube just hadn’t entered the adjacent possible in the mid-1990s—and even six or seven years later than that. Most people connected to the Internet via glacially slow dial-up modems, present company included. I remember the days of Prodigy and AOL. I couldn’t contain my excitement when I connected at 56 kbps. Of course, those days are long gone, although evidently AOL still counts nearly three million dial-up customers to this day.8 YouTube never would have taken hold if external factors didn’t let it (e.g., online storage didn’t drop in price by orders of magnitude, broadband connections hadn’t mushroomed, and digital cameras and smartphones didn’t democratize videos). Absent these factors, YouTube would never have been possible, much less remotely successful—and Google certainly wouldn’t have gobbled it up for $1.65 billion in 2007.

Ron Adner makes a similar point about electric cars in his 2012 book The Wide Lens: A New Strategy for Innovation. A company may possess the technology and desire to build a gasoline-free car, but that’s hardly the only relevant consideration. Nobody will actually want to buy one unless at least two critical conditions are met:

After all, we drive cars for two very simple reasons: we need to go places (such as to the office, the dentist, and the supermarket), and we want to go to other places (such as vacations, golf courses, and ballet recitals). Sure, we may hate paying $4/gallon at the pump, and most of us should know that the supply of oil is finite. But the current system works—at least for the time being. We know that we can get to where we need to go and return to our homes. The same just isn’t true for electric vehicles, at least as of this writing.

Well, we may not be able to say the same for long. Based out of Israel, Better Place is not only building affordable electric cars. As discussed, that’s only half the battle. The company is also working with the Israeli government on developing a network of solar-powered charging stations for its electric vehicles. One without the other just doesn’t cut it. Meeting both conditions is necessary for battery-powered cars to become more than a pipe dream. Better Place is well on its way, as venture capitalists (VCs) essentially doubled down in November 2012.9

And Big Data is already following a similar trajectory. Organizations didn’t have to worry about parsing through large videos in 1997 because no one was going to wait six hours for a video to upload (if the Internet service provider’s [ISP’s] dial-up connection didn’t crash midway throught). Today, that’s no longer an issue and hasn’t been for years. Twenty years ago, sending an e-mail was laborious, so few people bothered to do it. Now, we have the opposite problem: because it’s so easy, 294 billion e-mails are sent every day.10 The same can be said for the early days of blogs, radio-frequency identification (RFID) chips, social networks, and many of the other sources of unstructured data that have exploded over the past ten years. And each innovation, each progression, increases the adjacent possible. New sources of data will continue to sprout.

PROJECTS AND MOVEMENTS

Chapter 7 of this book looked at some Big Data abuses and issues like privacy and security. Without repeating them all here, suffice it to say that Big Data can yield potentially inimical consequences. As we conclude, remember the quote at the beginning of this book from Big Data pioneer Sandy Pentland. Big Data has big potential and will transform society. In fact, this is already happening. In this section, I’ll briefly introduce three groups who take these issues seriously. They are currently working behind the scenes to make data not only bigger, but more democratic, portable, contextual, and relevant.

The Vibrant Data Project

Big Data can mean big abuse, but this doesn’t have to be the case. So says the folks behind The Vibrant Data Project (VDP). At a high level, the group lobbies for increased transparency around all this data. It asks a critical question: how can we make our data work for us and not against? At present and as discussed in Chapter 7, large corporations like Amazon, Apple, Facebook, and Google gather, store, and utilize a tremendous amount of data on their customers and users. By and large, these organizations use this data only for their own economic purposes. VDP would like to change that. The project seeks to foster “a conversation around core challenges for empowering a much more decentralized approach—where individuals retain more control over their personal data, collaboratively discover its value, and directly benefit from it.”11

The Vibrant Data Project is in its infancy, but it’s worth keeping an eye on. Remember that the NoSQL movement did not start with 120 projects; it started with one. As Big Data becomes bigger and more powerful, expect the number of concerned citizens, groups, and government agencies to increase.

The Data Liberation Front

VDP isn’t alone as an advocate of data transparency and democratization. Consider what some Google engineers are doing under the moniker The Data Liberation Front (DLF). DLF has a single modus operandi: to enable Google users to move their data in and out of the company’s products. That is, users should be able to export their data from—and, if desired, import it into—other products.

“We help and consult other engineering teams within Google on how to ‘liberate’ their products,” the DLF’s website reads. “This is our mission statement: Users should be able to control the data they store in any of Google’s products. Our team’s goal is to make it easier to move data in and out.”12

Now, some may trivialize this as a Google PR ploy. After all, the company operates under an increasing swarm of privacy concerns, and many of its wounds are self-inflicted. (Again, Chapter 7 had plenty to say about this.) For the time being, it appears as if DLF is legitimately trying to raise awareness of a key issue raised by Big Data: who owns all this data in the first place? It’s a contentious issue that will only increase in importance.

Open Data Foundation

As discussed earlier, many organizations struggle with managing their own internal and structured data. These organizations lack a common understanding. For instance, Jack and Jill work for the same company, but they have different ideas about the definition of the term customer. (Many businesses lack a common understanding of basic but critical terms.) But what if that problem went away? What if everyone was on the same page in that company?

Now think bigger. What if people, businesses, and governments in Africa, Iceland, and the United States all used the same metadata? What if we all knew what we meant across different languages? Sound impossible? It’s not. Metadata standards will eventually make this dream a reality, in the process improving libraries, biology, archiving, the arts, and many more areas of our lives. More formally, metadata standards are requirements intended to establish a common understanding of the meaning or semantics of the data. When in place, they ensure the correct and proper use and interpretation of the data by its owners and users.

To be sure, you won’t overhear too many people talking about metadata standards at your local Starbucks. And they may not change your life tomorrow. Rest assured, though, they’re important, they’re coming, and their effects will be transformative. Metadata standards will enable and expedite the arrival of the semantic web.23

Organizations like the Open Data Foundation (ODaF) are working on these standards as we speak. According to its website, ODaF is

a non-profit organization dedicated to the adoption of global metadata standards and the development of open-source solutions promoting the use of statistical data. We focus on improving data and metadata accessibility and overall quality in support of research, policy making, and transparency, in the fields of economics, finance, healthcare, education, labor, social science, technology, agriculture, development, and the environment.

The foundation sees this information as primarily statistical in nature. At the same time, though, it understands that these standards can be drawn from a variety of sources, some of which may be unconventional.13

As we saw in Chapter 2, accurate metadata makes all data more relevant and contextual.

BIG DATA WILL ONLY GET BIGGER…AND SMARTER

Without question, more of the unwired masses will connect to the Internet in the coming years. Collectively, humanity will produce even more data than it does today through an increasing array of devices. The growth of mobility is intensifying, and soon smartphones will penetrate the developing world. While citizens in impoverished nations may not be able to afford the latest iPhone or iPad, growth may come from one former tech bellwether that has recently fallen tough times.

Research in Motion (RIM) has all but ceded the U.S. smartphone market to the Apple, Google, HTC, and Microsoft. Desperately trying to remain relevant, RIM is aiming for the lower end of the market. In May 2012, new CEO Thorsten Heins announced that his company would be pursuing “markets in the developing world” that would account for much of the company’s future revenue.14 Whether people in Congo, Liberia, and Zimbabwe buy BlackBerrys en masse is anyone’s guess. (I have my doubts, and I certainly won’t be buying RIM shares anytime soon.) Still, smartphone prices keep falling, with no end in sight. If it’s not the BlackBerry that helps close the digital divide, perhaps it will be the ultra-low-cost Aakash, an Android-based tablet computer with a 7-inch touch screen, ARM 11 processor, and 256MB of RAM.15 Regardless of which devices bring computing to the impoverished masses, it’s a safe bet that each year more and more people will connect to the Internet—making Big Data even bigger.

But let’s forget human beings for a moment: there are only so of us on the planet. More and more devices are now independently and automatically generating data. As the following examples show, advanced technologies and smart devices are starting to supplant their “dumb” counterparts. The implication for Big Data: it will only get bigger.

THE INTERNET OF THINGS: THE MOVE FROM ACTIVE TO PASSIVE DATA GENERATION

Web 1.0 allowed hundreds of millions of people to consume content at an unprecedented scale and rate, but only very technically savvy folks could produce it. As discussed in Chapter 1, around 2005 or so, Web 1.0 gave way to Web 2.0. For the first time, laypersons (read: nontechies) were able to generate their own data. As a result, enormous amounts of text, audio, and video content flooded the web. Of course, not everyone is happy with the proliferation of “amateur” content. Perhaps the most vocal critic is Andrew Keen, author of the controversial book The Cult of the Amateur. Keen pines for the good old days in which the gatekeepers had a tighter grip on the means of production.

Keen can whine all he wants, but no one can put the Internet genie back in the bottle. What’s more, regardless of how you feel about the ability of musicians to circumvent proper record companies and authors to self-publish their work, one thing can’t be denied: the democratization of content creation tools has produced a whopping amount of data.

That data is going to grow at an even faster rate thanks to the Internet of Things, a term coined by Kevin Ashton in 1999. In short, the term represents an increasing array of machines that are connecting to the Internet just as people have—and its consequences are profound. Ten years after introducing it, Ashton reflected on where we are going:

We need to empower computers with their own means of gathering information, so they can see, hear and smell the world for themselves, in all its random glory. RFID and sensor technology enable computers to observe, identify and understand the world—without the limitations of human-entered data.

In other words, let’s say that we existed in a world in which computers knew everything there was to know—using data gathered without any help from us. In this world, we could track and count everything. In the process, we would greatly reduce waste, loss, and cost. In Ashton’s view, we would know when things needed replacing, repairing, or recalling, and whether they were fresh or past their best.

Think of the Internet of Things not as more tech jargon, but as an inevitable development with profound implications. Germane to this book, it will only make Big Data, well, bigger. Machines will automatically create more and more data, perhaps even more than human beings currently do. Stated differently, the Internet of Things represents a sea change in who will be generating the most data—or, more precisely, what will be generating the most data.

At present, human beings are directly responsible for a high proportion of all data produced. This data begins with eyes on screens and fingers on mice, keyboards, smartphones, tablets, and PCs. Now, I don’t want to overstate things here. Our own data-generating activities aren’t going the way of the fax machine anytime soon. Billions of people will continue to blog, buy things, upload YouTube videos, tweet, text, make phone calls, search the web, and pin photos. All of this will still produce massive amounts of data, mostly the unstructured and semi-structured kinds. For the most part, sentient human beings have actively generated the most data. But what about more passive activities such as the myriad things that happen (or don’t happen) in a supermarket? Isn’t there potentially valuable data to be gleaned? The answer, of course, is yes.

Hi-Tech Oreos

For instance, Betty, a female shopper, picks up a box of Oreos, looks at it, appears to read its nutritional content, decides not to purchase it, and finally puts it back on the shelf. Historically, absent video cameras or in-store spies, not much could be gleaned from that nontransaction. Now, consider that same scenario, but in a Big Data world with ubiquitous, low-cost RFID tags, sensors, near field communication (NFC), and other powerful technologies.

What part of the packaging did Betty appear to read? Did specific images or words resonate with her more than others? What were her nonverbal expressions when she saw the number of carbs per serving? Exactly how long did she hold the box in her hands? Did Betty look at any other types of cookies, and for how long? Was she with anyone, like her children? Did her daughter say anything during that time? Was she a former Oreophile? Is this behavior markedly different in Safeway, Walmart, and other supermarkets? Why?

In the near future, consumer product companies will be able to quickly and easily capture and store immense amounts of product- and customer-specific data from physical stores. Advances in technology will allow these Oreo-related questions (and, many, many more) to be answered for the first time. Equipped with this information, the marketing folks at Nabisco can tweak the package color or fonts and analyze the effects of those changes. Perhaps they’ll find “the right” combination of each. What if they find that a one-size-fits-all package doesn’t make sense, even within the same country? It’s entirely possible that different people buy Oreos for different reasons, and packaging can be customized just like television advertisements. Big Data and related technologies are making all this possible and, in the future, easier.

Hi-Tech Thermostats

How do you follow up the über-successful iPod? It’s a question that Tony Fadell, the man who designed the hardware for Apple’s breakthrough product, had to face. After working on eleven consecutive models of the iPod, Fadell left Apple and decided to take on a much different challenge. Why not try to make thermostats hip? After a good deal of tinkering, the Nest Thermostat was born.

Forget for a moment the fact that Nest just looks cool and is brain-dead simple to use. As a Wired article by Steven Levy16 points out, the device connects to Wi-Fi networks, enabling two important things. First, Nest users can set temperature remotely via their iPhones. (One can imagine a day in the not-too-distant future in which we won’t have to wonder if we’ve left the oven on after leaving the house. We will be able to just turn it off remotely.) The broader, more important implication of devices like Nest is that they generate data specific to each customer. This data can be easily collected and sent to websites, allowing people to track temperatures in their own homes—and even “learn” about their own personal temperature preferences. Nest will “know” that you like your home warmer at night in the winter (say, 71 degrees) but a bit cooler during the day. In the summer, your preferences change, and so will the temperature in your home—without your having to do anything.

Thermostats are only the beginning. You don’t need to buy a high-tech Nest Learning Thermostat to realize some of the benefits of Big Data. Electricity as we know it is changing. Smart meters and grids are coming to a city near you—and soon. I’ll be the first to admit that many people will find this odd. After all, historically, utilities haven’t exactly been technological trailblazers. The reasons aren’t terribly difficult to discern. Electric companies basically hold local monopolies. It’s not as if their customers can easily switch from Utility A to Utility B. To boot, many are in fact nonprofits. And let’s not forget what they’re selling: electricity, a service that is anything but optional. (Economists describe products like these as having a high elasticity of demand.) There’s really no substitute for electricity, although candles and a Wi-Fi connection at Starbucks helped me survive a storm and subsequent power failure in northern New Jersey for several painful days back in 2010.

Consider what one utility company is doing. Established way back in 1935, EPB is a nonprofit agency that provides electric power to the people around Chattanooga, Tennessee. It is one of the largest publicly owned electric power distributors in the country. Using a 100 percent fiber optic network as its backbone, EPB is moving ahead full-steam with smart grids. The company’s digital smart meters communicate with its power system. Much like a traditional electric meter with a dial, a smart meter measures its customers’ electric consumption. However, there’s a key difference: a smart meter remotely reports consumer consumption every 15 minutes. By contrast, traditional meters are usually read manually, and only once per month. In what will no doubt become standard in a few years, consumption levels are displayed digitally on the meter. As of this writing, this information is available for EPB customers to view online, on a channel or application, or over a Wi-Fi network. From the company’s website:

Smart meters also help us keep an eye on things as they happen. So, by fall of 2012, if there is a power outage at your home or business, we’ll know within 15 minutes and can get to work fixing the problem immediately! And if we notice an unusual or substantial increase in your power consumption, we can notify you so you can investigate.17 [Emphasis added.]

An electric company that proactively notifies its customers when their usage levels increase? Perish the thought! E-mails or texts that alert people to what’s happening! You can see before your bill arrives that you’re on track for a $300 charge and can make adjustments accordingly. And EPB has company here. At some point in the near future, smart grids will become standard. Can water companies be far behind? What else will technology and Big Data disrupt?

Smart Food and Smart Music

We’ve heard for a while now about smart refrigerators (i.e., those that will read the expiration date on milk cartons and automatically remind you to buy new milk or even order it for you). But an expiration date isn’t terribly personal. What about a refrigerator that will help people diet and eat better? Far-fetched? Hardly. In January 2012, I attended the Consumer Electronics Show (CES). At the event, LG announced

an array of new products to its Smart ThinQ appliance line. At the forefront of its new line is its refrigerator, which just got a lot smarter with a health manager feature that allows you to maintain your diet, send recipes to your smart oven, and even keeps you posted when you run out of certain groceries.18

In the future, my refrigerator will recommend different dishes than yours, even if we own the same model. And why shouldn’t it? I probably eat differently than you do. Our data is different.

You probably don’t eat what I eat, nor do you like the same music that I do. Thanks to the Big Data revolution and attendant technologies, we can more easily “consume” only what we like. Consider Echo Nest, founded by two MIT Ph.Ds. The company utilizes Big Data tools to analyze music. It provides this data to consumer-facing music services such as iHeartRadio, eMusic, MOG, Spotify, Nokia, the BBC, and VEVO. In total, more than 15,000 developers use Echo Nest data to create and enhance apps. Echo Nest’s Fanalytics service analyzes the usage patterns and history of every person using a music service, “including the person’s music collection, listening habits, and other factors. Then applications can match similar profiles. In addition, the service can provide ‘affinity prediction.’ [I]n other words, it can predict how music preferences predict political affiliation—or perhaps eventually other consumer habits such as purchasing or brand preferences.”19

Welcome to a world of metapredictions: predictions about other predictions. Think of services like Echo Nest as a kind of Netflix for music. Thanks to Big Data and related tools, your food and music are going to get smarter.

BIG DATA: NO LONGER A BIG LUXURY

Many of the factors described in this book regarding the arrival of the Big Data revolution can be summed up simply: progressive people, organizations, and institutions like Billy Beane, Quantcast, NASA, Explorys, Target, and the city of Boston are embracing Big Data because they foresaw considerable benefits. However, there’s arguably a more crucial reason for leveraging Big Data: survival. In other words, we have no choice. Forget Target making a few more dollars from expecting mothers. It’s an instructive example, but consider the following harrowing story.

In October 2011, the city of Harrisburg, Pennsylvania, declared bankruptcy. The Wall Street Journal reported that the state’s capital city “filed for bankruptcy protection from creditors Wednesday, in a case closely watched by other cities and towns looking for ways out of dire financial troubles. Including Harrisburg, there have been 48 bankruptcies from cities, counties, towns and villages since 1980, according to James Spiotto,”20 a lawyer at Chapman and Cutler LLC in Chicago, Illinois, who specializes in laws affecting distressed municipalities. It’s a trend with a disturbing uptick, and many public officials are watching similar budget crises in Wisconsin, California, and other places with keen interest.

STASIS IS NOT AN OPTION

Count among the onlookers Mayor Menino of Boston, the driving force behind Street Bump. We met him in the Introduction to this book. Now, Boston doesn’t appear to be on the verge of bankruptcy anytime soon, but that doesn’t mean that it can’t operate in a more innovative, efficient, and data-oriented manner. (What organization can honestly make that claim?) Rather than fight to maintain the status quo, Menino has decided to push the envelope—and he should be commended for doing so.

Menino launched Street Bump to much fanfare, but don’t call it a publicity or a reelection stunt. Nor was Street Bump an attempt to brand the city as progressive or hip. Boston doesn’t need much help there; increasing its “cool factor” was just an ancillary benefit. So why?

The answer lies on the New Urban Mechanics’ website:

New Urban Mechanics is an approach to civic innovation focused on delivering transformative City services to Boston’s residents. While the language may sound new, the principles of New Urban Mechanics—collaborating with constituents, focusing on the basics of government, and pushing for bolder ideas—are not.21

In fact, Mayor Menino (known as the Urban Mechanic) has been preaching this mantra for years. He uses technology and Big Data to further his constituents’ specific interests. In the process, he has become Boston’s longest serving mayor, and this city has received its fair share of national kudos.

More succinctly, as Menino writes on the same site, “We are all urban mechanics.” Menino is smart enough to know that government must innovate to survive and provide the essential services demanded by its citizenry. Stasis is no longer an option.

Today, many government-funded Big Data projects are largely driven by economic imperative. The emphasis is often on avoiding sticks (very difficult fiscal and budgetary climates, looming layoffs) more than embracing carrots (increased innovation, better functionality, and generally more responsive government). I’ll do my best to remain apolitical here. At least in the United States, we can blame individual politicians, Congress, Democrats, Republicans, special interests, “the system,” or any or all of the above for our current budgetary predicament.

The fact remains that budgets are shrinking with no end in sight. As Thomas L. Friedman and Michael Mandelbaum write in That Used to Be Us: How America Fell Behind in the World It Invented and How We Can Come Back, the status quo is simply untenable. The U.S. federal, state, and municipal governments will have to do much more with less—and soon. (Outside of the United States, there’s also plenty of opportunity for governments across the globe to both cut expenses and expand their current services. For instance, I’ve never been to Greece, but I imagine that the country has potholes to go along with its economic malaise.) In ways like this, Big Data is a means to an end—and a necessary one at that. Given the current economic and budgetary climate, expect many more Big Data projects like Street Bump in the coming years. We simply have no choice.

SUMMARY

Business leaders and government officials need to spur innovation (with Big Data playing a big part) while concurrently balancing very real privacy and security concerns. Yes, the benefits of Big Data can help the public sector combat—but not overcome—the difficult economic times we’re all facing. But our elected officials need to go much deeper than react to budget crises. Government should innovate; our politicians shouldn’t need the excuse of shrinking budgets to embrace new technologies and Big Data. Progressive public officials like Menino, San Francisco Mayor Ed Lee,24 and others clearly believe in a fundamentally different way of doing things than traditional, change-resistant bureaucrats, and Street Bump is a case in point. Along these lines, Tim O’Reilly has written and spoken extensively about the need for government to become a platform. For that platform to reach its full capacity and accrue benefits to its citizens, Big Data can—nay, must—play an integral role. Initiatives like Data.gov25 certainly represent steps in the right direction. I am one among many who would like to see much more in the way of openness, common standards, collaboration, and innovation.

NOTES

1. Heubsch, Russell, “What Is the Profit Margin for a Supermarket?,” 2012, http://smallbusiness.chron.com/profit-margin-supermarket-22467.html, retrieved December 11, 2012.

2. Brownell, Matt, “Can Retailers Beat the ‘Showrooming’ Effect This Christmas?,” October 22, 2012, www.dailyfinance.com/2012/10/22/christmas-shopping-showrooming-online-price-match/, retrieved December 11, 2012.

3. Tuttle, Brad, “Best Buy’s Showrooming Counterattack: We’ll Match Amazon Prices,” October 15, 2012, http://business.time.com/2012/10/15/best-buys-showrooming-counterattack-well-match-amazon-prices/, retrieved December 11, 2012.

4. Owen, Laura Hazard, “Following Target, Walmart Stops Selling Kindles,” September 20, 2012, http://gigaom.com/2012/09/20/walmart-following-target-stops-selling-kindles/, retrieved December 11, 2012.

5. Duhigg, Charles, “How Companies Learn Your Secrets,” February 16, 2012, www.nytimes.com/2012/02/19/magazine/shopping-habits.html?pagewanted=2&_r=1&hp, retrieved December 11, 2012.

6. Ibid.

7. Cukier, K., “Data, Data Everywhere,” February 25, 2010, www.economist.com/node/15557443, retrieved December 11, 2012.

8. Aguilar, Mario, “3 Million Suckers Still Pay for AOL Dial-Up,” July 27, 2012, http://gizmodo.com/5929710/3-million-suckers-still-pay-for-aol-dial+up, retrieved December 11, 2012.

9. Woody, Todd, “Better Place Raises $100 Million as Investors Double Down on Electric Car Bet,” November 1, 2012, www.forbes.com/sites/toddwoody/2012/11/01/better-place-raises-100-million-as-investors-double-down-on-electric-car-bet/, retrieved December 11, 2012.

10. Tschabitscher, Heinz, “How Many Emails Are Sent Every Day?,” April 9, 2012, http://email.about.com/od/emailtrivia/f/emails_per_day.htm, retrieved December 11, 2012.

11. “We the Data—Why We Do This,” 2012, http://wethedata.org/about/why-we-are-doing-this/, retrieved December 11, 2012.

12. “The Data Liberation Front,” November 30, 2012, www.dataliberation.org/home, retrieved December 11, 2012.

13. “The Open Data Foundation,” 2012, www.opendatafoundation.org/, retrieved December 11, 2012.

14. Faas, Ryan, “RIM Falls Flat Trying to Hype Third World Sales as a Major Success,” May 3, 2012, www.cultofmac.com/164814/im-falls-flat-trying-to-hype-third-world-sales-as-a-major-success/, retrieved December 11, 2012.

15. http://timesofindia.indiatimes.com/home/sunday-toi/special-report/We-want-to-target-the-billion-Indians-who-are-cut-off/articleshow/10284832.cms

16. Levy, Steven, “Brave New Thermostat: How the iPod’s Creator Is Making Home Heating Sexy,” October 25, 2011, http://www.wired.com/gadgetlab/2011/10/nest_thermostat/, retrieved December 21, 2012.

17. Levy, Steven, “Brave New Thermostat: How the iPod’s Creator Is Making Home Heating Sexy,” October 25, 2011, www.wired.com/gadgetlab/2011/10/nest_thermostat/, retrieved December 11, 2012.

18. Murphy, Samantha, “A Refrigerator That Helps You Diet? LG Unveils High-Tech Smart Appliances,” January 9, 2012, http://mashable.com/2012/01/09/lg-smart-refrigerator/, retrieved December 11, 2012.

19. Geron, Tomio, “Echo Nest Raises $17 Million for Big Data Analysis of Music,” July 12, 2012, www.forbes.com/sites/tomiogeron/2012/07/12/echo-nest-raises-17-million-for-big-data-analysis-of-music/, retrieved December 11, 2012.

20. Corkery, Maher; Michael, Kris, “Capital Files for Bankruptcy,” October 13, 2011, http://online.wsj.com/article/SB10001424052970204002304576626752997922080.html, retrieved December 11, 2012.

21. “New Urban Mechanics—About,” 2012, www.newurbanmechanics.org/about/, retrieved December 11, 2012.

22. Amazon’s net profit margin typically hovers at around 2 percent and has trended downward over the past few years. (See: ycharts.com/companies/AMZN/profit_margin.) By way of contrast, Apple’s has been north of 30 percent over the past few years.

23. For more here, see David Siegel’s excellent book Pull: The Power of the Semantic Web to Transform Your Business.

24. Lee is modernizing city government, starting with high-tech super cops. See http://tinyurl.com/a9r3ecz.

25. Data.gov seeks to increase public access to high-value, machine-readable datasets generated by the Executive Branch of the Federal Government. For more, see www.data.gov/about.