One

WHERE THE FLICKER SHOWS WERE

At the dawn of the 20th century, the motion picture had just recently made its public debut with the kinetoscope. Hand-cranked machines located in downtown penny arcades showed the minute-long “flicker shows” through a peephole. Films were soon edited into 5- and 10-minute features, and new projectors put them on screens. The only places big enough to show these photoplays and photodramas were dark storerooms often infested with bugs and mice. These were soon replaced with buildings designed especially as theaters, charging 5¢ admission. These nickelodeons were clean, comfortable, and vermin-free.

Mostly working-class folks patronized the nickel shows, but general audiences were growing. Programs changed weekly and usually included five different films: a drama, comedy, adventure, novelty, and documentary or other short feature with accompaniment by a live piano or organ. Nickelodeons lasted until around 1910 and were either renovated to accommodate the larger crowds or closed, unable to compete with the big theaters being built around the Queen City.

Folks developed interesting new habits as they got used to stepping out to see the picture shows. They read the title cards out loud. They chatted and shared recipes. Nobody minded, because that was what happened during the show. Prime advertising space was utilized on the screen just like today. In addition to the coming attractions, slides promoting local businesses were shown. The main feature then appeared on the screen and generally lasted an hour and a half, followed by serials, comic shorts, and newsreels. Hollywood studios soon began releasing full-length feature films such as Birth of a Nation in 1915 (shown at the Grand Theater in 1917), and admission rates soared by 10¢ or more.

These were the days before air-conditioning. Cold refreshments were sold during the shows, and attendants walked the aisles squirting disinfectant to freshen the air. The primitive projection equipment was not always reliable, and the nitrate film was flammable. At the Grand Theater in June 1917, two small explosions occurred in the projector and a fire broke out in the booth. The projectionist extinguished the flames while the audience of 200 calmly filed out to the current melodies played by the organist.

Upon a movie’s release, distributors sent the films directly to the first-run theaters. Second-run houses received them next, and by the time the films arrived at the small third-run suburban theaters, the abused film had been repaired with chewing gum, safety pins, hairpins, and sometimes even horseshoe nails. The projectionist made repairs before showtime. Whenever the film broke during the show, the projectionist fixed it while audience members booed, yelled, and stomped their feet.

Moviegoers tended to drop a lot of personal articles in the theaters. During comedies, small items fell from their pockets while they were laughing at the slapstick antics onscreen. In melodramas or action films, patrons tore or crushed their belongings in the excitement. Among the items in the lost-and-found bin at the Walnut Theater in 1920 were a porcelain tooth, a stethoscope, gold and jeweled fraternal pins, class pins, a gold watch, watch fobs, earrings, bracelets, a string of beads, scores of eyeglass cases, gold pocket pieces and stick pins, gold and silver cufflinks, shoes, gloves, ties, belts, scarves, fur pieces, pocketbooks, a wallet containing $98, and a purse containing $500. Most of these went unclaimed.

Sound effects like chirping birds and train whistles in early-1920s movies came from a record playing on a specially equipped phonograph, usually poorly synchronized with the film. In 1926, Warner Brothers Vitaphone films introduced high-quality sound and voice on a specialized accompanying record. The first talkie—The Jazz Singer, starring Al Jolson—opened in 1927. Lights of New York premiered in 1929 as the first movie to feature all-synchronous dialog. Soon after, theaters that showed the new sound films proudly proclaimed, “Not a Vitaphone.”

The technology that pioneered radio in the 1920s brought television in the 1940s. Hollywood was now being delivered right to living rooms. Theaters simply could not compete with this exciting new medium. Among others, the Hiland Theater, in business for 24 years in Fort Thomas, closed in April 1950 after a sudden decrease in attendance. The owners blamed it on the growing number of television-equipped homes.

True, television helped bring the downfall of movie houses, but social change had a major influence as well. Soldiers returning from the war were getting married, and their incomes had to put food on their families’ tables. Soon after 1945, about 15 theaters closed. At this time, Americans were being deluged with advertising for new and improved major appliances—washing machines, dishwashers, refrigerators, vacuum cleaners, as well as new postwar automobiles. Television dealers urged prospective customers to skip going out to see movies and instead finance monthly payments for new appliances and television sets.

RKO decided to take advantage of this new technology in 1951 and installed big-screen television sets in the Lyric and other Midwest RKO theaters. They planned to broadcast theater-direct programs as well as sporting events, primarily boxing matches. Folks actually went to the theaters to watch televised boxing, but the concept eventually failed, and the Lyric closed in 1952.

The Capitol Theater introduced Cinerama to a dazzled public in 1952. The old movie house was partially rebuilt to house the three giant screens and additional projectors. Since attendance was dropping, however, it was too expensive for Hollywood to produce Cinerama movies. The more economical wide-screen Cinemascope format was developed and remains the standard.

In October 1954, the Esquire Art Theater opened on Ludlow Avenue in Clifton. It featured a small, intimate setting with comfortable seats and a wide screen set some distance from the front row. The Esquire began with Walt Disney’s latest, The Vanishing Prairie, and continues to show art-house movies today.

The super wide-screen format Todd-AO was introduced in early 1958, and a few Cincinnati theaters were equipped for it. This technology employed a giant, curved screen that gave the audience a convincing, undistorted illusion of depth.

The automobile made countless permanent changes in the urban landscape, and drive-in theaters began appearing in the 1930s. The Montgomery Drive-in, located on Montgomery Road, opened in 1939 and boasted the largest screen in the Midwest. After World War II, drive-ins added playgrounds and children’s activities to attract the city’s growing families. In 1949, the Mo-Tour In drive-in theater opened near Milford. It held 750 cars and catered almost exclusively to the family crowds. Other drive-ins included the Oakley, the Auto-In on Anderson Ferry, the Dent Auto, the Mount Healthy, the Starlite in Amelia, the Woodlawn, Acme Auto in Glendale, Riverview on Route 8, Dixie Gardens in Fort Wright, and the Florence Drive-in.

Magic and romance normally occurred on the movie screen, but one night in October 1958 there was romance actually on the movie screen. The happily engaged Peggy Roettele and Al Elmes were married atop of the 80-foot-high screen of the Twin Drive-In on Reading Road. They thought this would be a fun way to get married, and the theater gave its blessing. After the nuptials, they immediately left for their honeymoon in Mexico, not sticking around to see Reform School Girls, The Amazing Colossal Man, Vertigo, and King Creole.

The decade of the 1950s was the most popular for drive-ins. Always looking to draw more families and bigger crowds, theaters added extra gimmicks: train and pony rides, boats, miniature golf, and talent shows. Drive-ins peaked at nearly 5,000 nationwide in 1958 but began dropping off by 1960. Closings became widespread through the 1960s and 1970s with some spaces converted to flea markets, while most stood vacant, overgrown with weeds and trees. A minor revival occurred in the 1990s, and even today many folks still enjoy watching the new releases at the drive-ins.

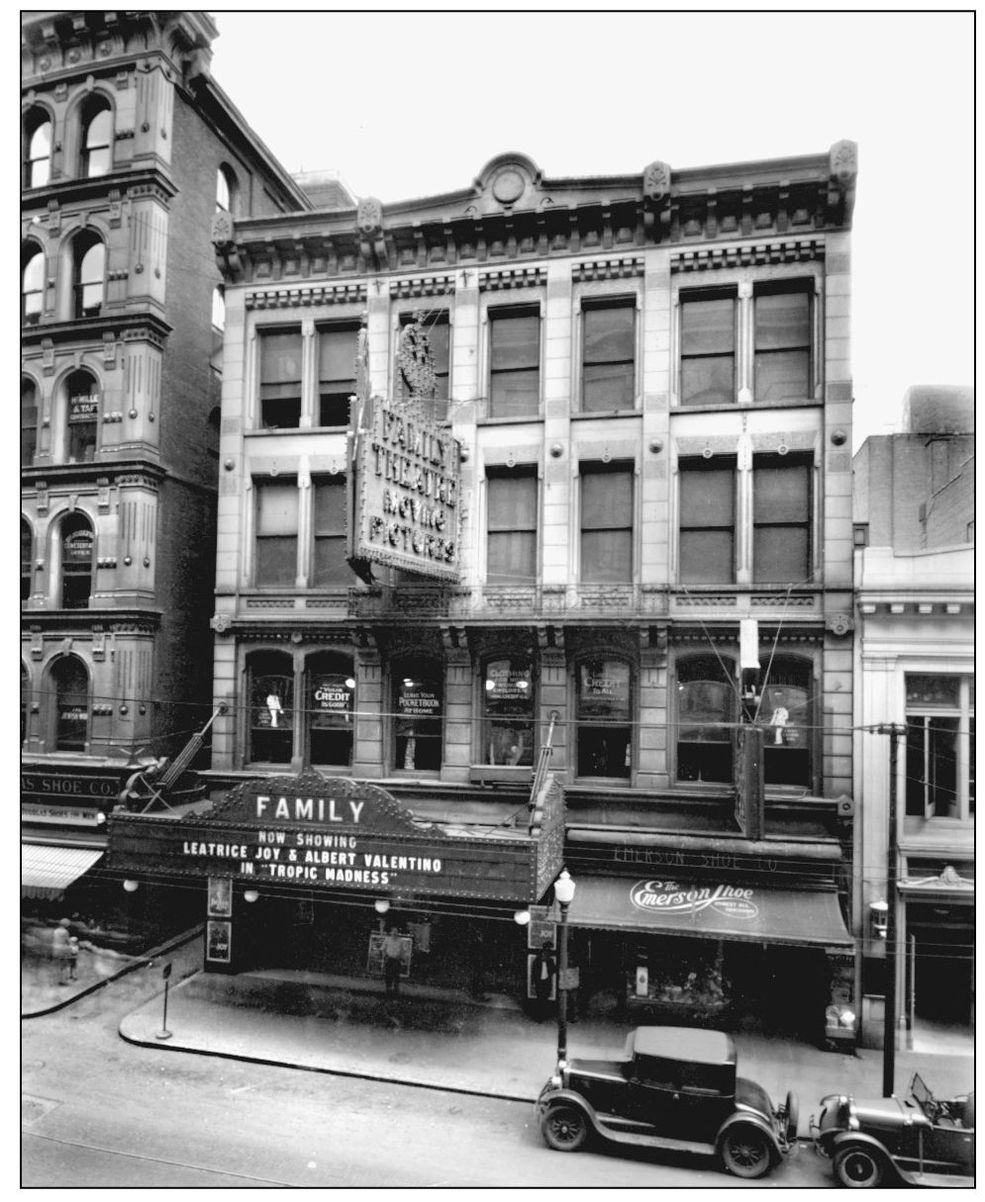

In the early 20th century, much of downtown Cincinnati was populated with buildings constructed before the Civil War, like the Gazley Building, which housed the Family Theater. This week in 1928, folks caught continuous performances of stage shows alternating with screenings of Tropic Madness, starring Leatrice Joy and Albert Valentino. The Emerson Shoe Company shared the first floor, and a clothing store operated on the second floor. (Photograph by W. T. Myers and Company; courtesy of Bill Myers.)

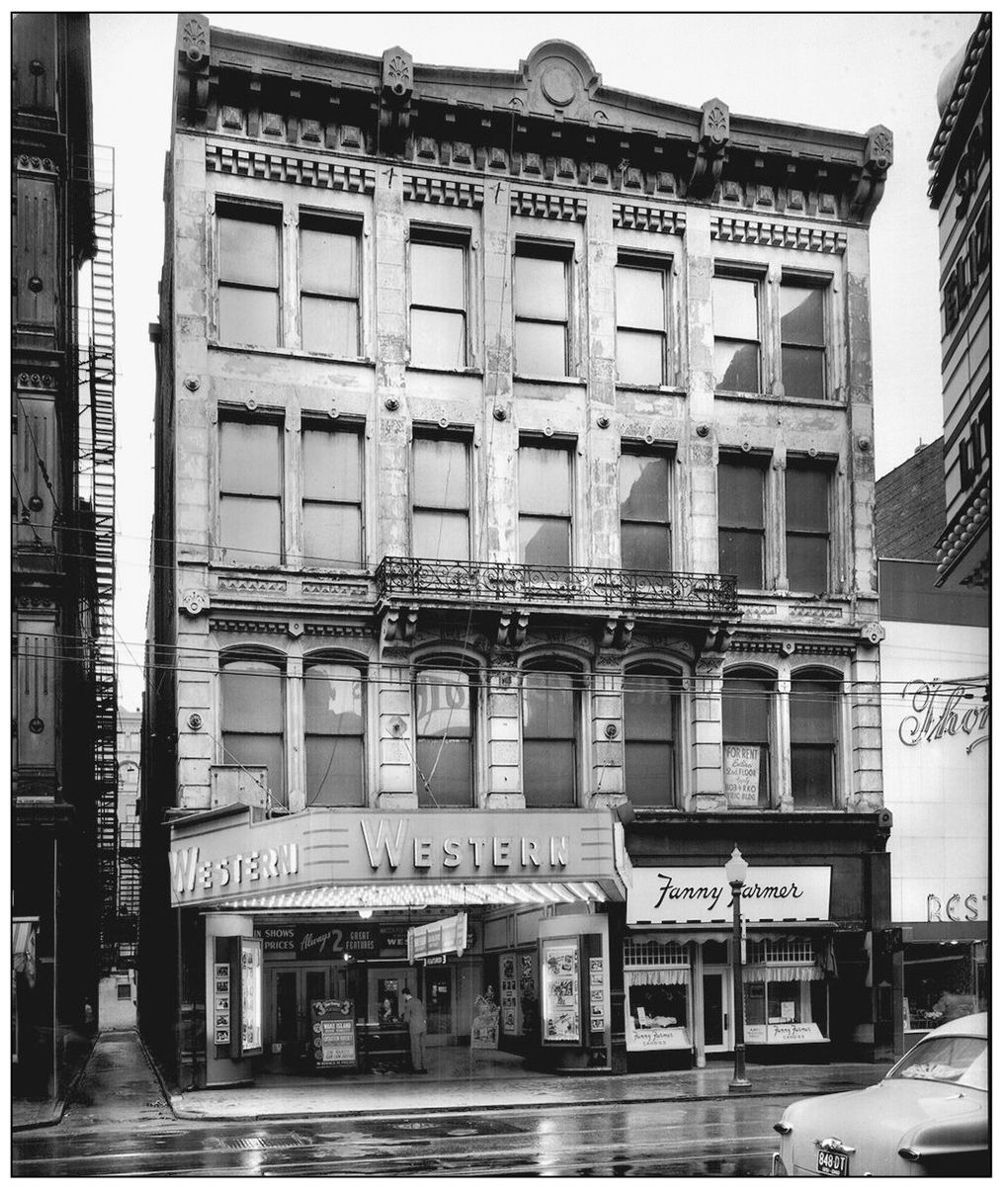

The Family became the Western in the 1940s, showing triple features of action films and westerns. In 1951, Wake Island, Operation Haylift, and Gun Law Justice showed on the screen. When the old Lyric Theater was razed in 1952, the Western was remodeled and renamed the New Lyric and opened in January 1953 as a second-run house. It closed on November 25, 1953, and was torn down four years later. (Photograph by Ben Rosen; courtesy of www.cincinnatihistory.com.)

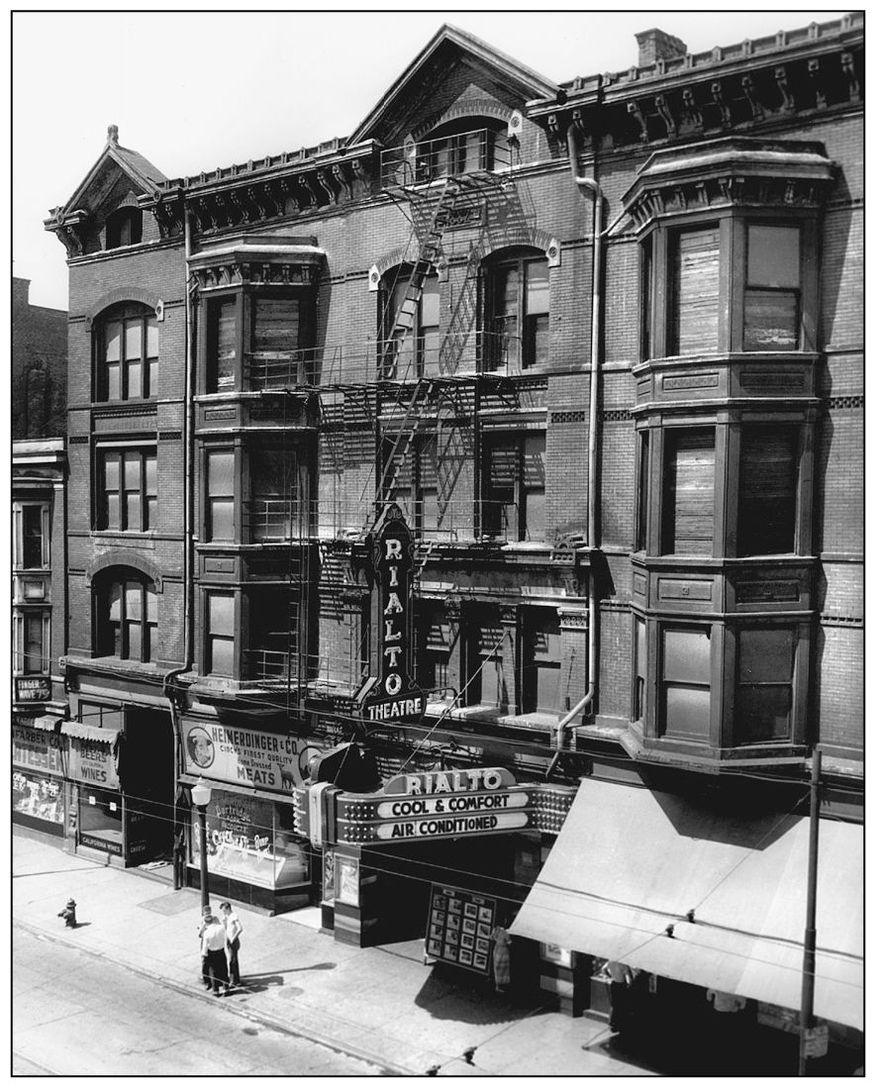

Heuck’s Opera House opened in 1882 at 1221 Vine Street in Over-the-Rhine. In the early 1900s, it showed theater and melodrama and turned to high-class burlesque in 1919. Heuck’s shifted focus to movies and became the Rialto Theater in 1926, showing first-run movies and seating 1,500. In late 1958, the theater closed when its building was condemned. It was razed in July 1959 and turned into a parking lot. (Photograph by Ben Rosen; courtesy of www.cincinnatihistory.com.)

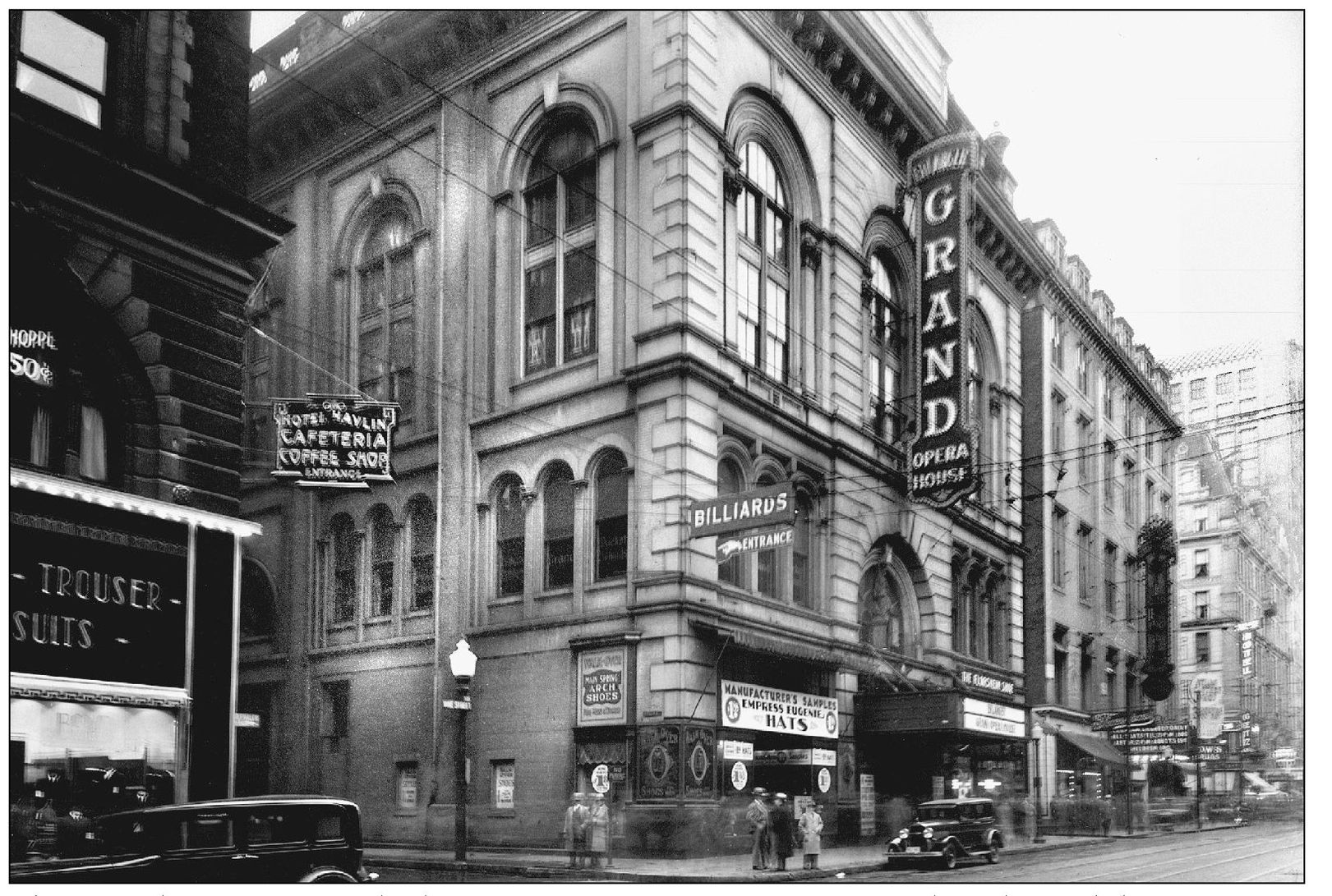

The Grand Opera House, built in 1859 on Vine Street at Opera Place, burned down in 1901. Rebuilt and modernized, the 2,100-seat theater opened in 1902 with live stage performances from Klaw and Erlanger. Picture shows were included in 1928, and legitimate theater was discontinued in 1932. The rebuilt Grand was torn down in 1939 and replaced with the new Grand Theater, which seated 1,500. (Photograph by Ben Rosen; courtesy of www.cincinnatihistory.com.)

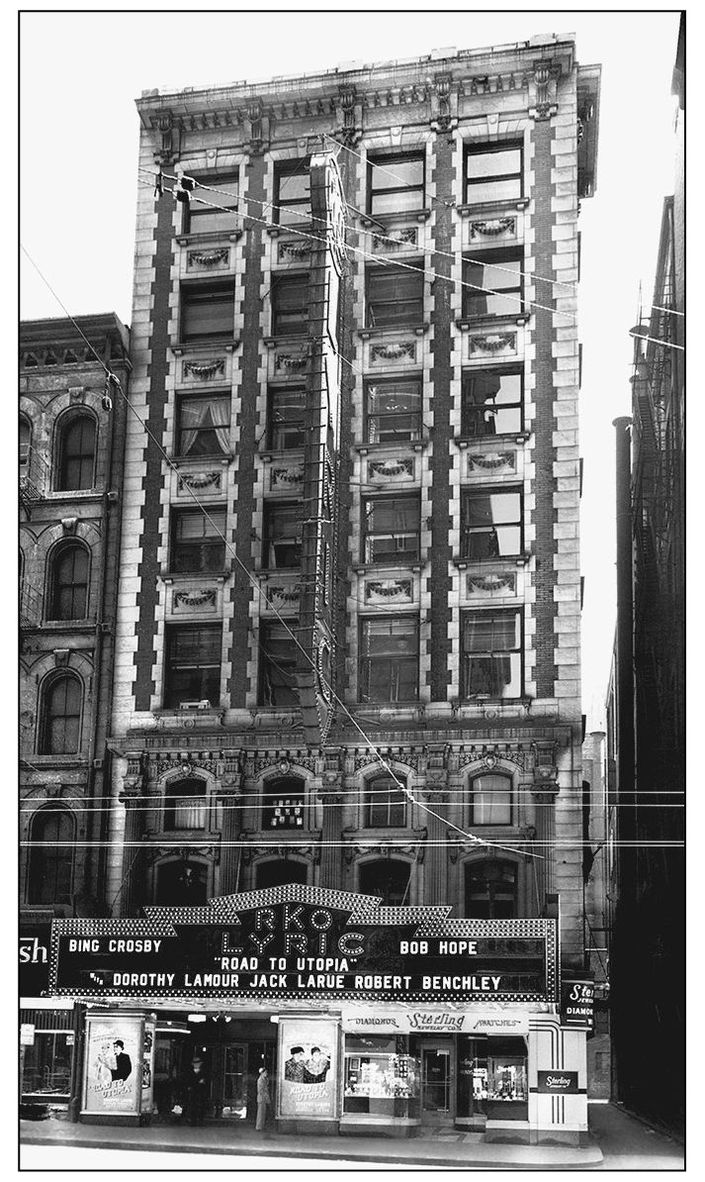

Across the street from the Grand and next door to the Family was the Lyric at 508 Vine Street, Cincinnati’s other legitimate early-20th-century theater. After opening in 1906, the Lyric presented local musicals, vaudeville, and dramas including Chu Chin Chow, Aphrodite, and Morosco’s Bird of Paradise. In this scene from 1946, the Lyric is showing Road to Utopia, starring Bob Hope and Bing Crosby. (Photograph by Ben Rosen; courtesy of www.cincinnatihistory.com.)

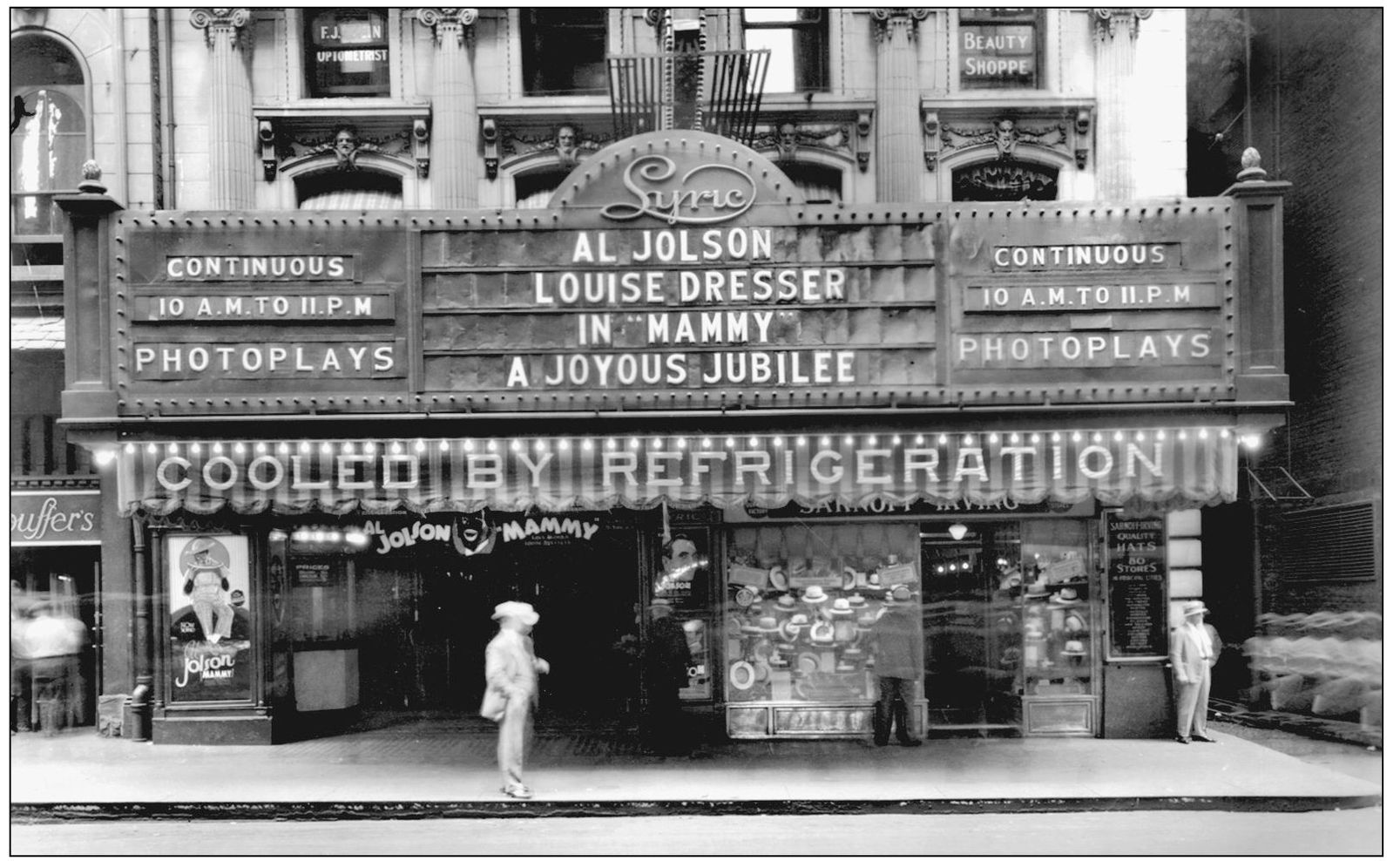

To keep current with changing times, the Lyric remodeled and added photoplays in 1918, and the 1920–1921 season was its last for legitimate theater. In 1921, the house added vaudeville from the Pantages circuit, with a continuous bill from noon to midnight. By 1930, the Lyric offered productions from 10 a.m. to 11 p.m., this particular week showing the film Mammy, starring Al Jolson. (Photograph by W. T. Myers and Company; courtesy of Bill Myers.)

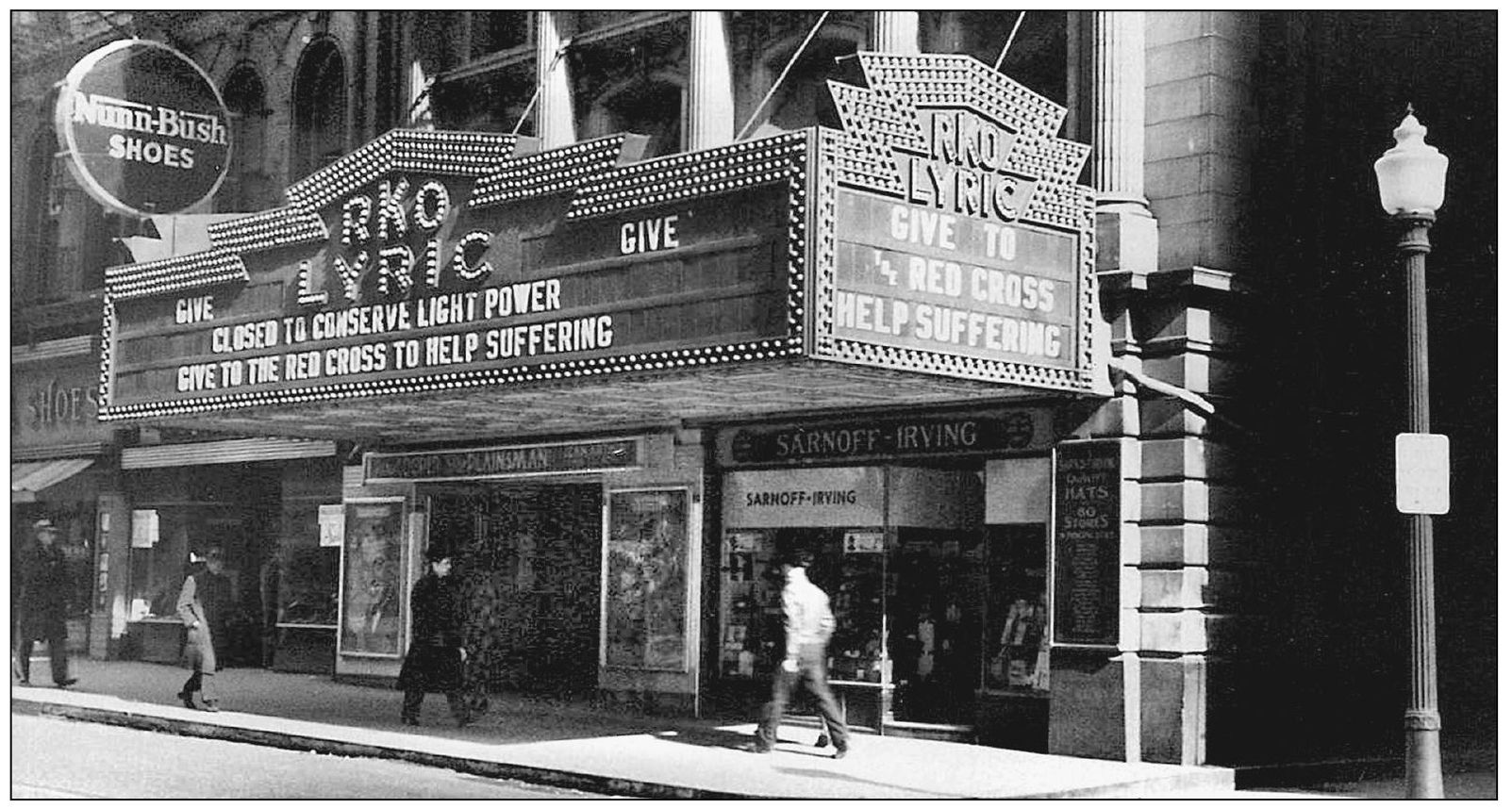

The January 1937 flood impacted many downtown businesses. Showing the week the Lyric was forced to close was Cecil B. DeMille’s The Plainsman. The theater’s marquee claims that it closed to “conserve light and power.” Cincinnati at the time was recovering from the flood, and folks were not going out to see the movies that month. The Lyric finally closed on December 1, 1952, and was soon replaced with a parking lot. (Photograph by Ed Kuhr Sr.; courtesy of the Dan Finfrock Collection.)

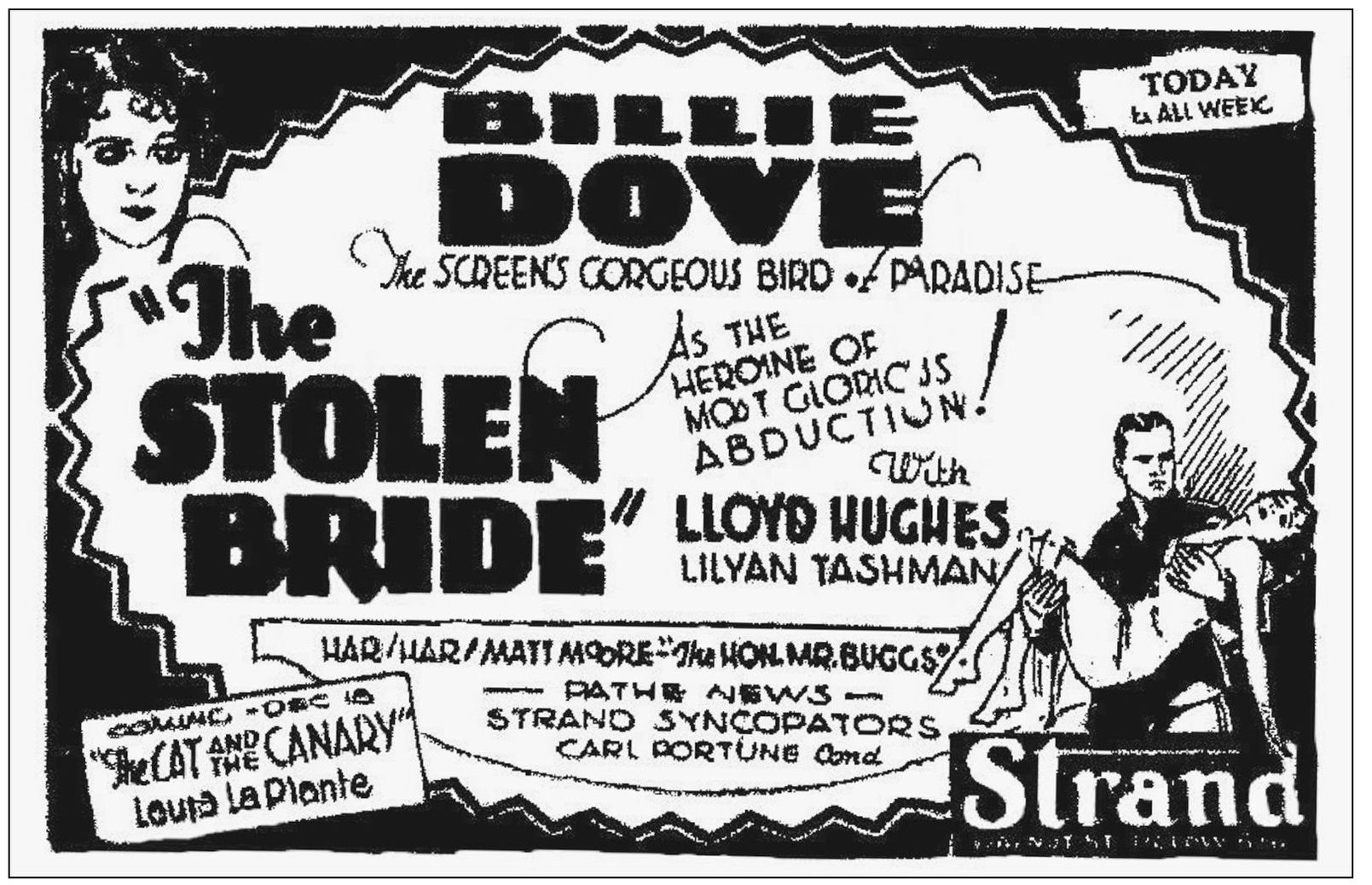

Newspaper advertisements for recent motion pictures often looked as interesting as the films. In December 1927, the Strand showed Billie Dove in the silent feature The Stolen Bride. Also on the bill were The Honorable Mr. Buggs, with Oliver Hardy of Laurel and Hardy; Pathe News; and the Strand Theater’s own Strand Syncopators, conducted by Carl Portune. Next week was the thriller The Cat and the Canary, starring Laura LaPlante. (Courtesy of the Commercial Tribune.)

In September 1925, the Walnut ran The Freshman and the romantic comedy Lovers in Quarantine. This week at the Capitol, Gloria Swanson appeared in The Coast of Folly; next week’s big feature was the romantic drama Graustark, with Norma Talmadge. The Lyric presented the groundbreaking dinosaur film The Lost World. Next week at the Lyric was the premiere of another huge picture: Charlie Chaplin’s The Gold Rush. (Courtesy of the Cincinnati Post.)

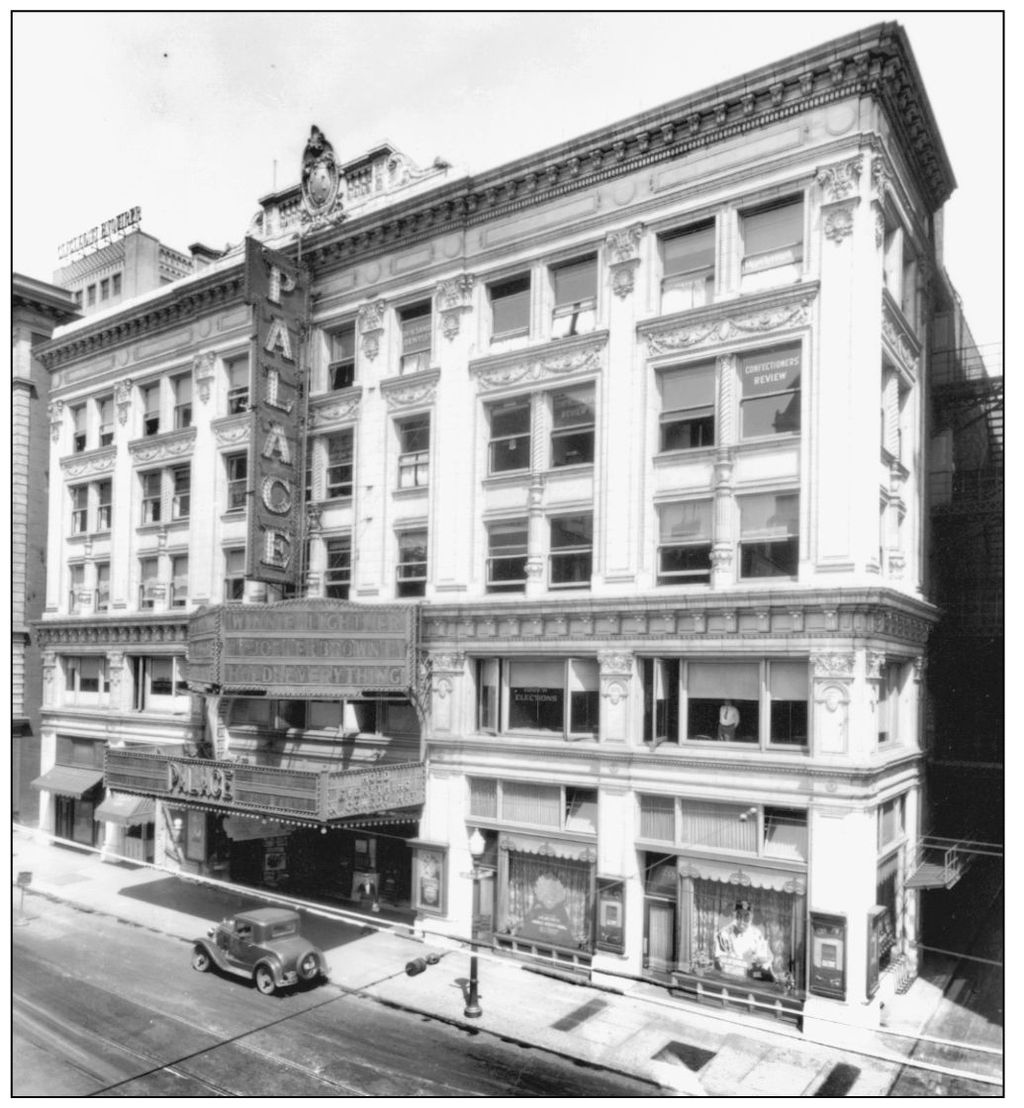

The Palace Theater, the self-proclaimed “most modern theater in the Midwest,” opened at 12 East Sixth Street in December 1919. It was the first stop for national topflight, popular-priced vaudeville acts. Shows ran continuously from noon until 11:00 p.m. with regular appearances by George Burns and Gracie Allen. Talking pictures were introduced in 1928. On the screen this week in 1930 were Hold Everything and the cartoons Dixie Days and Aesop’s Fables. (Photograph by W. T. Myers and Company; courtesy of Bill Myers.)

Moviegoers heading for the Palace this week in 1930 would have seen Clara Bow in the romantic comedy True to the Navy. Also showing was the musical short Pick ’em Young, starring Robert Agnew, as well as Movietone News. Audience members would have felt great relief inside the theater, since the Palace had just recently installed air-conditioning. A cool theater was a welcome treat during Cincinnati’s hot summers. (Photograph by W. T. Myers and Company; courtesy of Bill Myers.)

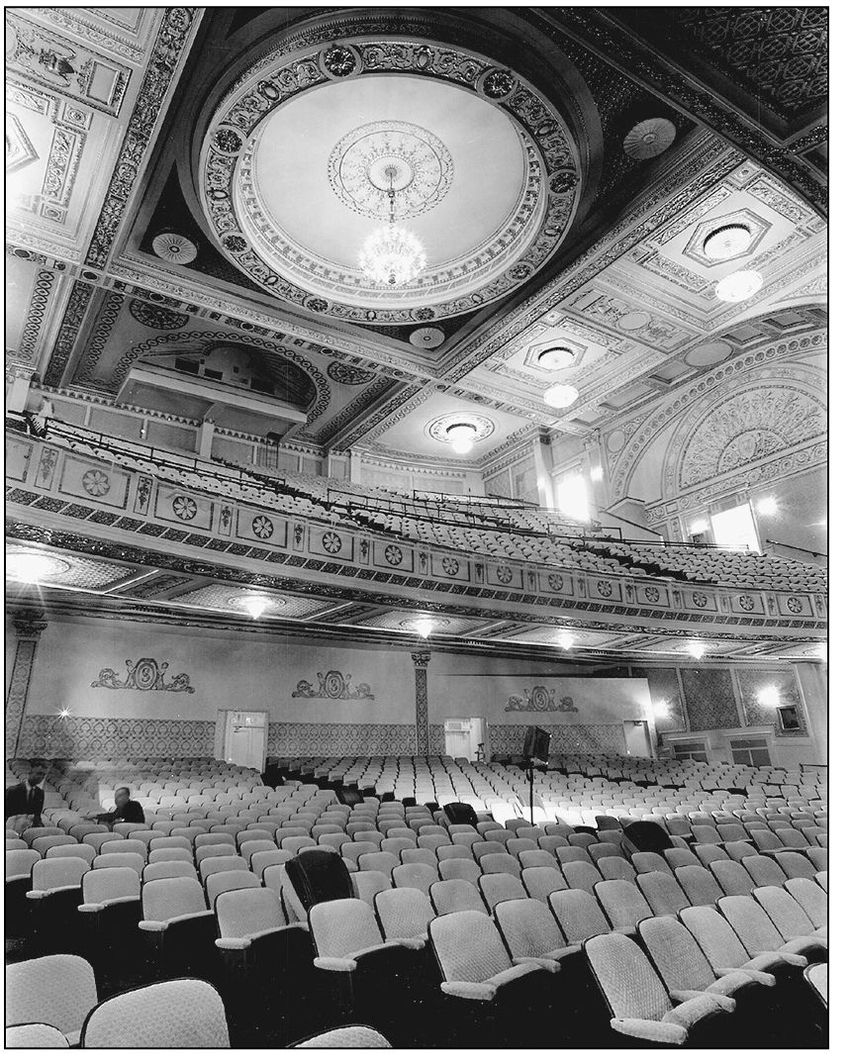

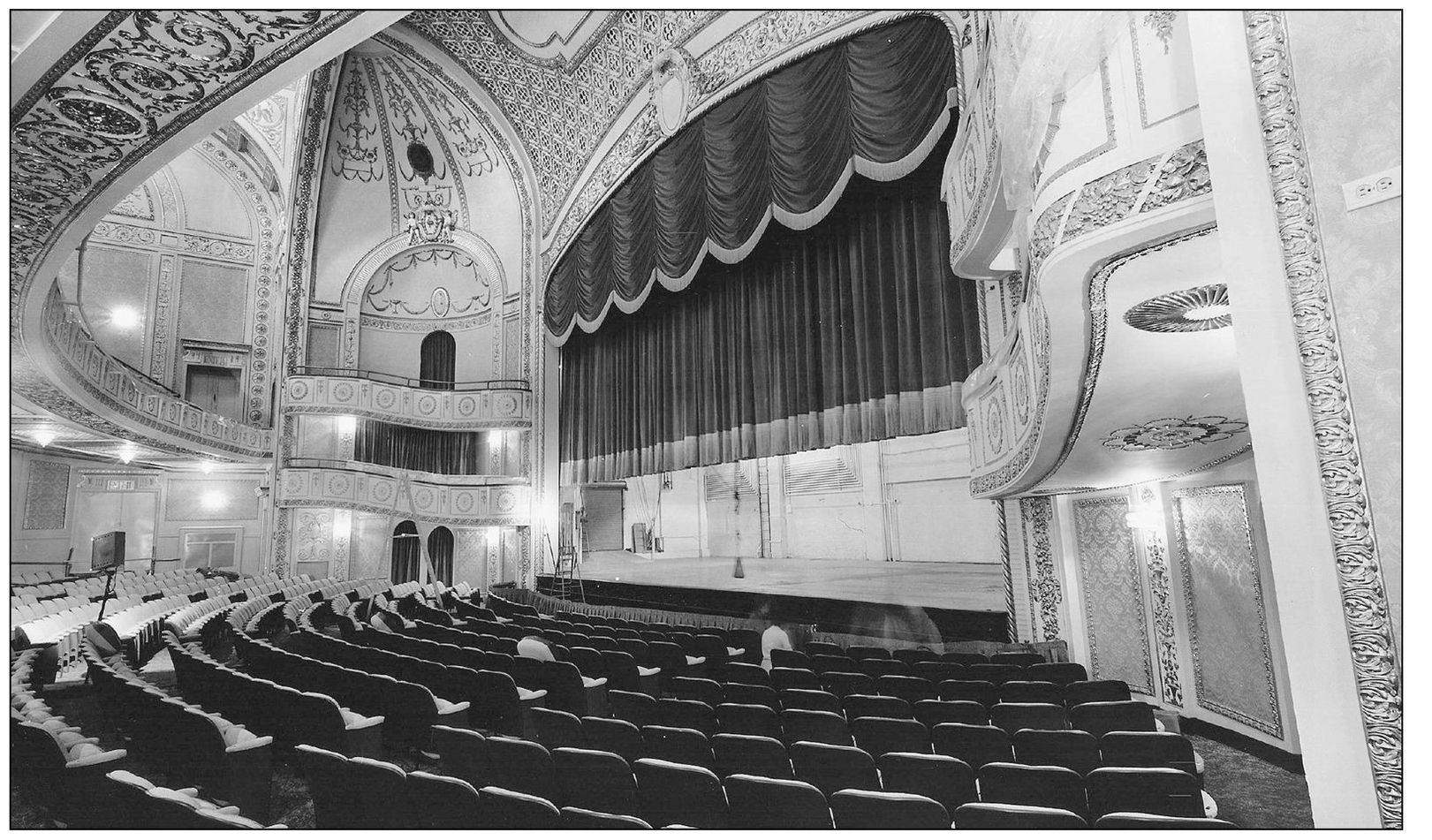

Plush red carpets covered the floors of the Palace’s foyer and promenade, and the color scheme included mulberry, cream, and gold. Patrons enjoyed restrooms, three women’s rooms, three gentlemen’s smoking rooms, and 2,800 seats in the theater. An overture by the house orchestra, directed by Harry Wiltsee, preceded every show. Hy C. Geis played the pipe organ during the breaks between the stage show and movie. Tickets were 30¢. (Photograph by W. T. Myers and Company; courtesy of Bill Myers.)

The Palace became the RKO International 70 in the late 1960s and featured such major motion pictures as 2001: A Space Odyssey, The Godfather, and Earthquake. Here in 1975, Let’s Do it Again is on the screen. The RKO International 70 closed in 1978. After a remodeling, it reopened in 1980—once again as the Palace, featuring movies, concerts, Broadway shows, and symphonic evenings. The concept failed to takeoff and the Palace closed in 1981 and was torn down the next year to make way for the Linclay Corporation office building. (Photograph by Ben Rosen; courtesy of www.cincinnatihistory.com.)

“See and hear the world’s greatest entertainers” in the Capitol Theater at Seventh and Vine. When it opened in 1921, it boasted a pipe organ, the Teddy Hahn Orchestra, first-run films, and high-class vaudeville stage shows. This week in 1927 audiences went to see The Canary Murder Case. The nearby United Cigar Store sold after-show sundries to moviegoers. (Photograph by W. T. Myers and Company; courtesy of Bill Myers.)

Silent films thrived until 1927, when the talkies arrived with the Vitaphone, which was discontinued when Hollywood developed sound-on-film two years later. The first Cincinnati theater to feature Vitaphone was the Capitol. This week in 1930, Fannie Brice starred in Be Yourself. Nearly three decades later, in 1958, the Capitol featured Cinerama motion pictures—super wide-screen events. The Capitol was torn down in 1970 for a parking lot. (Photograph by W. T. Myers and Company; courtesy of Bill Myers.)

In September 1921, the Shubert Theater opened in a renovated YMCA building at Seventh and Walnut. The interior reflected the Renaissance style but lacked the glamour of the big palaces. Vaudeville shows and plays appeared on the stage, and in May 1930, it was wired for talking pictures. In 1935, RKO leased the Shubert for 20 years. Playing at the Shubert this week in 1959 was the Broadway smash Sunrise at Campobello. (Photograph by Ben Rosen; courtesy of www.cincinnatihistory.com.)

The Shubert daily alternated five vaudeville shows with movies from 11:00 a.m. to midnight in 1937. Entertainers often complained that the audiences came more for the B movies even though the Shubert delivered acts like Willie Howard, Jimmy Durante, Sally Rand, Paul Whiteman, Fats Waller, Glenn Miller, Glen Gray, Fred Waring, and Guy Lombardo. In 1956, it was remodeled with a white-and-gold color scheme and 2,000 seats. (Courtesy of the Cincinnati Musicians Association Archives.)

The Shubert was remodeled again in 1964, and an opening was cut through the back wall into the adjacent Cox Theater for storage. But the 1975 season was cancelled when touring companies refused to play Cincinnati after major declines in ticket sales. Cincinnatians bid adieu to the Shubert following its final show starring Redd Foxx. It was razed in January 1976 and replaced with a parking lot. (Courtesy of the Cincinnati Musicians Association Archives.)

The George B. Cox Memorial Theater was built on Seventh Street in 1920. For over 35 years, 1,500 small productions played at this intimate 1,300-seat house designed by “Boss” Cox’s widow and built flush against the Shubert. The Cox closed in 1954 after final performances of Misalliance, The Moon is Blue, and Dial M for Murder. In 1976, the Cox was demolished along with the Shubert. (Photograph by Ben Rosen; courtesy of www.cincinnatihistory.com.)

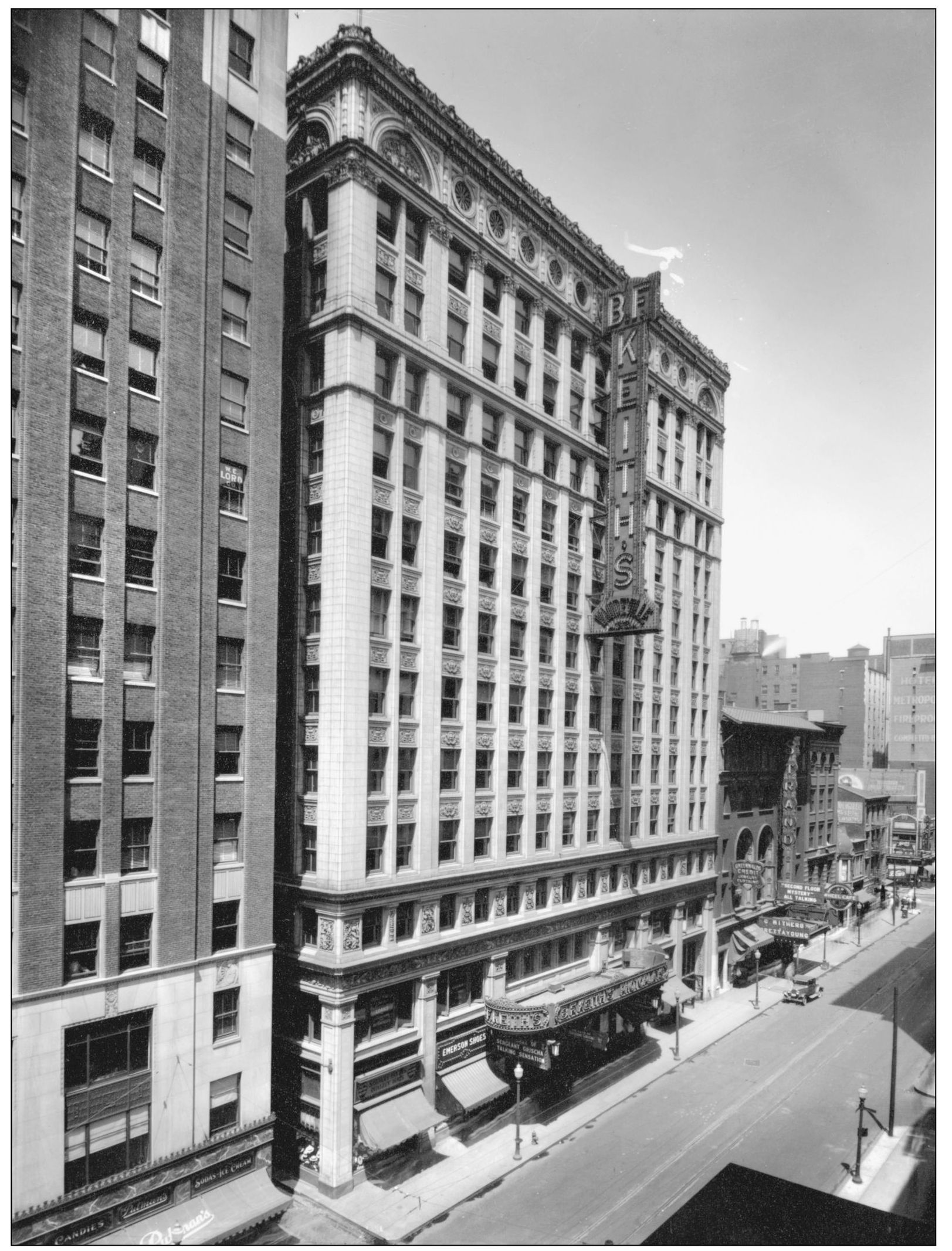

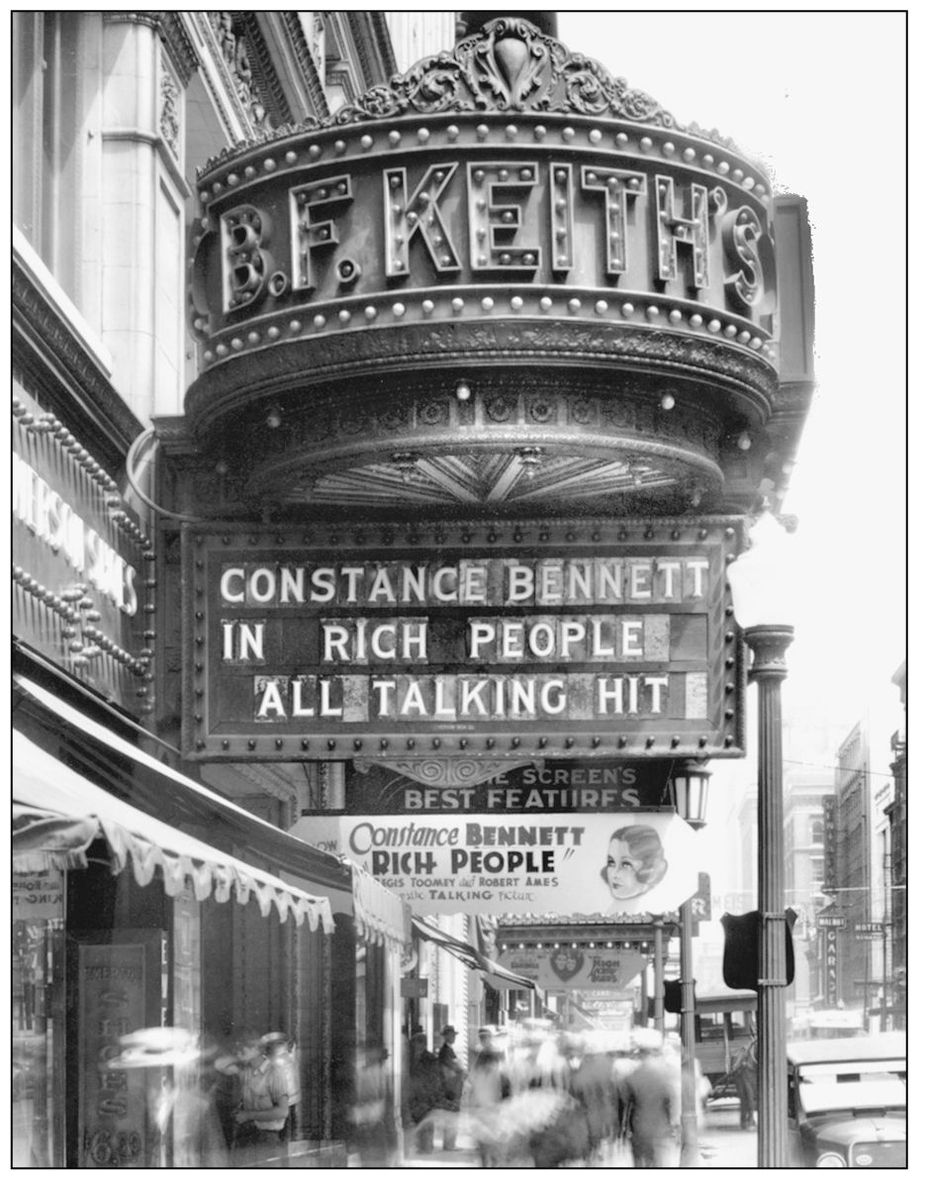

Though built after 1928, the Keith Theater, at 525 Walnut Street, had a long history. The original building housed the Fountain Theater, constructed in the 1880s. In 1899, the theater was remodeled and renamed the Columbia, which became one of the leading vaudeville houses in the nation. During this week in 1930, Keith’s was showing the Academy Award–nominated Sergeant Grischa. (Photograph by W. T. Myers and Company; courtesy of Bill Myers.)

The Columbia was remodeled again in 1909 and sold to B. F. Keith, who featured two daily vaudeville shows. In 1924, Keith presented sketch comedy acts, musicians, vaudeville routines, and jazz and classical singers. Acts like tap dancers, tumblers, singers, magicians, and blackface performers appeared at Keith’s for a week and then moved onto Chester Park for seven more days. On the screen this week in 1930 was Rich People. (Photograph by W. T. Myers and Company; courtesy of Bill Myers.)

In 1928, Keith’s discontinued vaudeville and turned its focus to talking pictures. Management wanted to expand, so the old Keith’s building was torn down and replaced with a 12-story building with the new Keith’s on the ground floor. Now 3,000 patrons could enjoy a film in modern surroundings. Other films besides Rich People this week were High Society Blues, with Janet Gaynor, and the animated short Barnum Was Wrong. (Photograph by W. T. Myers and Company; courtesy of Bill Myers.)

In 1946, Keith’s was renovated to feature Universal Pictures films. It reopened on Thanksgiving with the premiere of The Magnificent Doll, starring Ginger Rogers and Burgess Meredith. Rogers appeared in person at the grand reopening on behalf of the War Nurses Memorial Fund. In 1950, Keith’s was sold to an East Coast investment company. Films “Coming Soon” in 1965 included A Very Special Favor and Walt Disney’s The Monkey’s Uncle. (Photograph by Ben Rosen; courtesy of www.cincinnatihistory.com.)

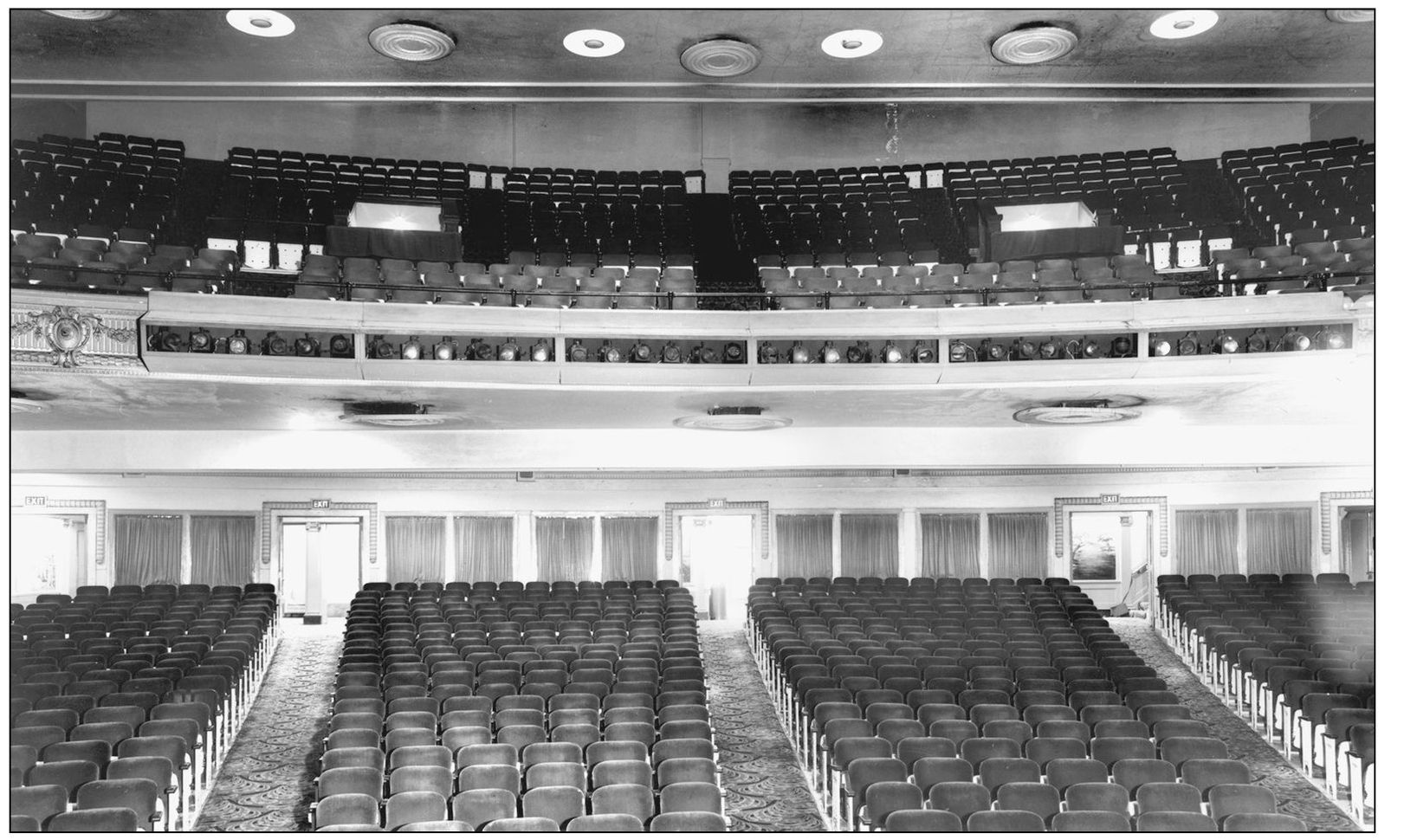

The inside of the modern Keith’s lacked the charm of some other downtown movie houses, although with two balconies, it was bigger than some. When the theater closed in 1965, tickets cost $2.50 during the week and $3 on weekends. It was torn down that September. (Photograph by Ben Rosen; courtesy of www.cincinnatihistory.com.)

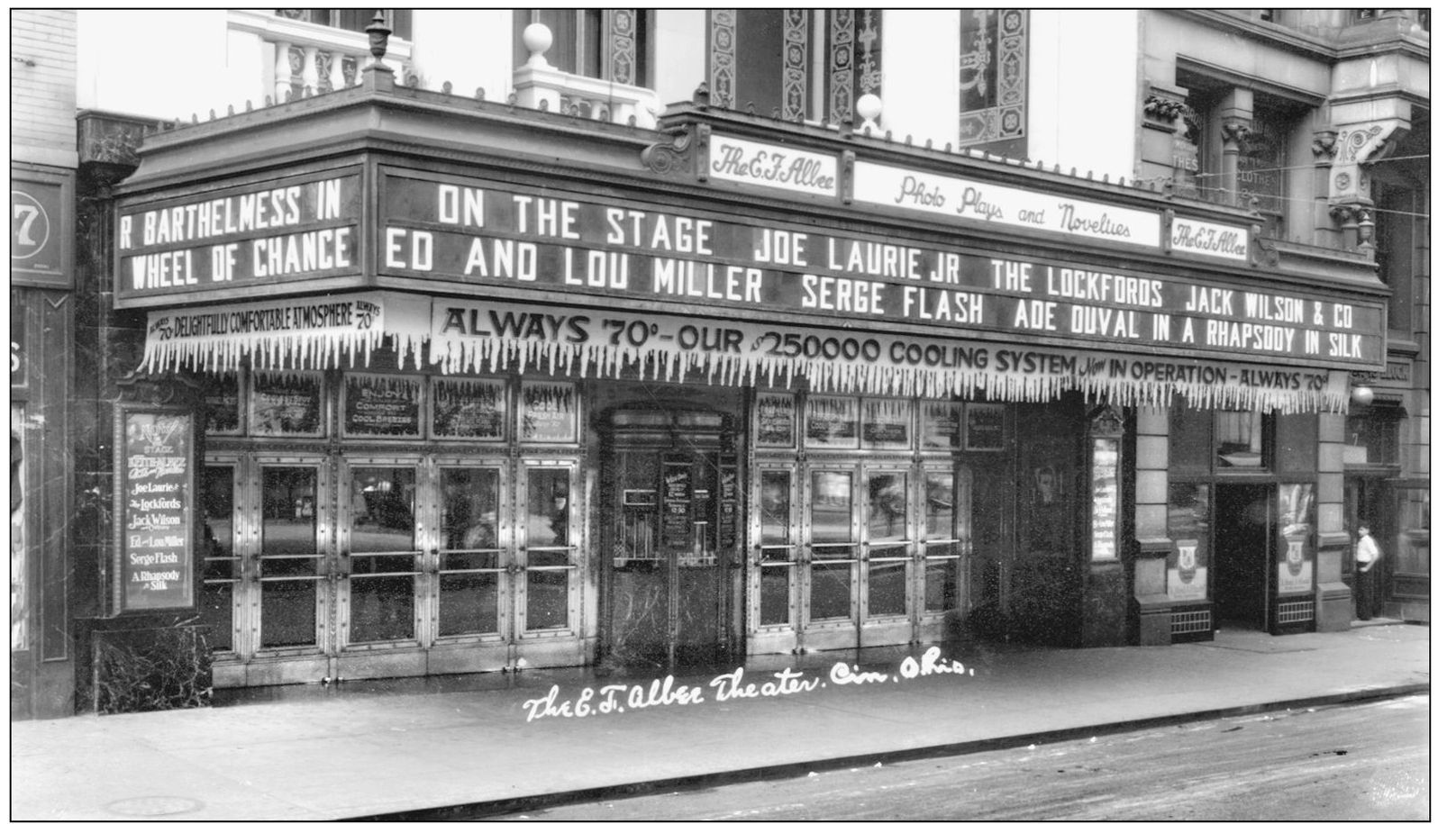

The E. F. Albee Theater opened on Fountain Square after Christmas in 1927. Photoplays and vaudeville “novelties” were big draws in 1930, with emphasis on music and talking as sound was a recent innovation. On screen this week was Office Scandal, and on stage was silent screen actress Leatrice Joy. Many film actors performed in vaudeville to prove they could speak, sing, and dance well enough to appear in the talkies. (Photograph by W. T. Myers and Company; courtesy of Bill Myers.)

Air-conditioning was a modern marvel in the 1920s. Patrons went to the theaters as much for relief from the heat as for the films. Showing this week on the screen in 1929 was the silent feature Wheel of Chance. The six-bills of vaudeville included Ade Duval’s magic act Rhapsody in Silk, juggler Serge Flash, “pint-sized” comedian Joe Laurie Jr., French acrobats the Lockfords, and singer Jack Wilson and Company. (Photograph by W. T. Myers and Company; courtesy of Bill Myers.)

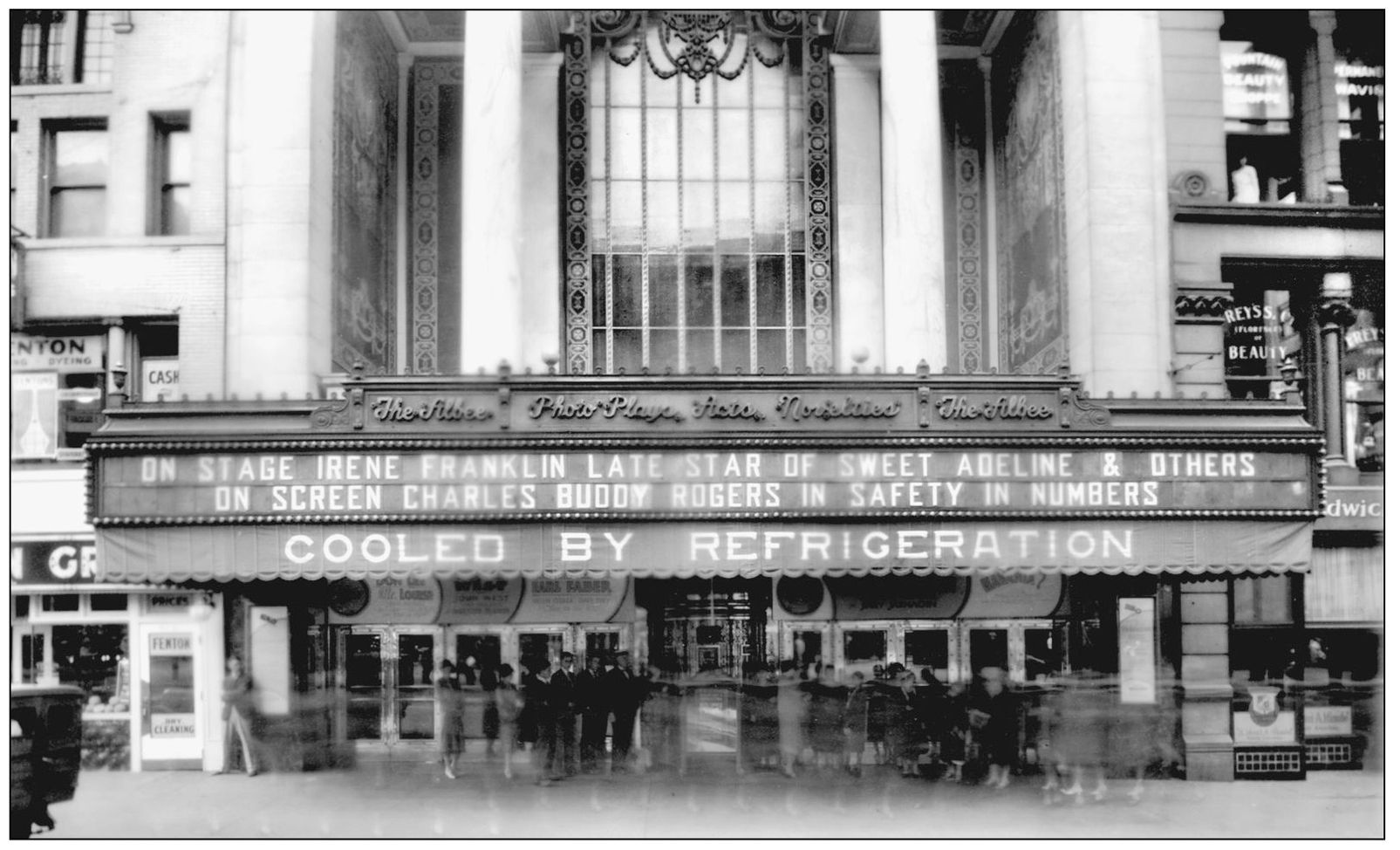

Patrons have lined up in 1930 to see the musical comedy Safety in Numbers, starring Charles “Buddy” Rogers. On stage this week was vaudeville and silent screen actress Irene Franklin. The country was just starting to sink into the Depression. Radio was gaining huge listenership as vaudevillians went to the airwaves. Vaudeville and burlesque wheels were shutting down, and soon announcements of vaudeville shows would stop appearing on the Albee’s marquee. (Photograph by W. T. Myers and Company; courtesy of Bill Myers.)

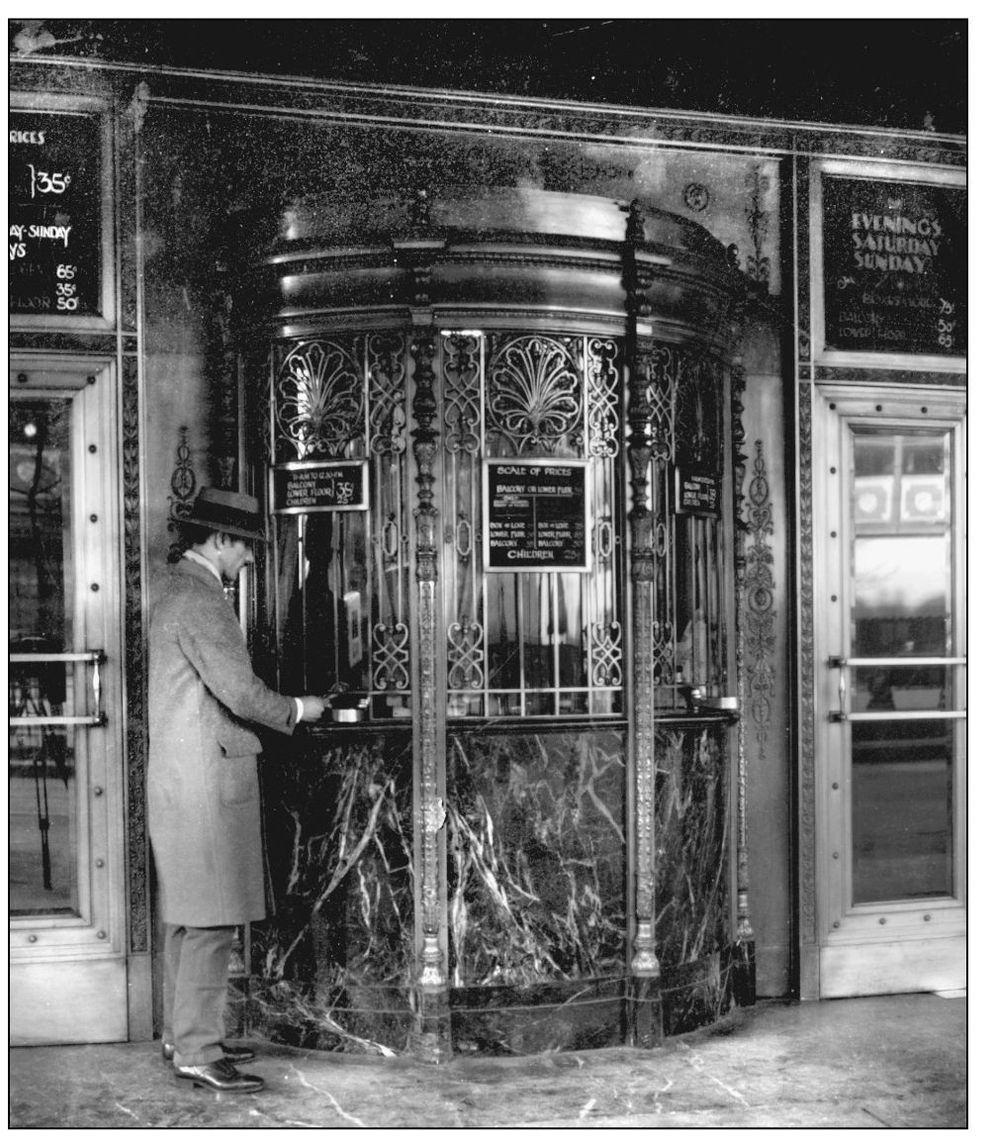

Moviegoers paid admission to the Albee at its ticket booth on Fifth Street. Tickets in 1930 cost 35¢ for both balcony and floor seats and 75¢ for box seats. Folks could hardly wait to get inside. The Albee delivered the ultimate in comfort and convenience in luxurious surroundings most Cincinnatians had never before experienced. The reflection of the camera’s tripod is visible in the door at the far left. (Photograph by W. T. Myers and Company; courtesy of Bill Myers.)

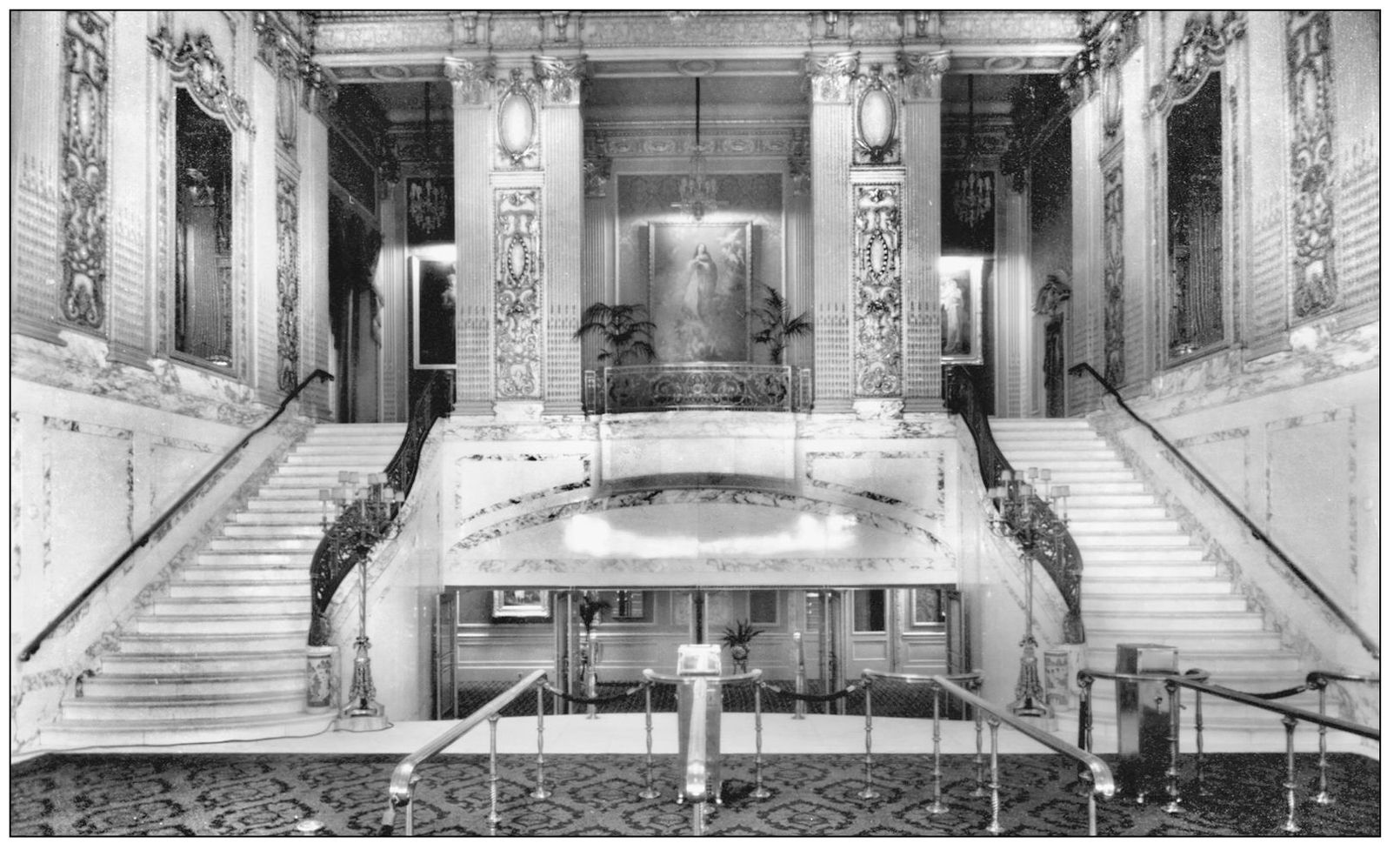

The Albee cost $4 million to build, and its décor was based on early European design. Cincinnatians marveled at the two-story stained-glass window, ornate plaster ceilings, and bronze staircases. It even contained a pool for aquatic acts. After purchasing a ticket, the patron ambled though this plush red-carpeted lobby and then down the stairs to the left to enter the auditorium. The upstairs corridor led to the gentlemen’s and women’s lounges. (Photograph by W. T. Myers and Company; courtesy of Bill Myers.)

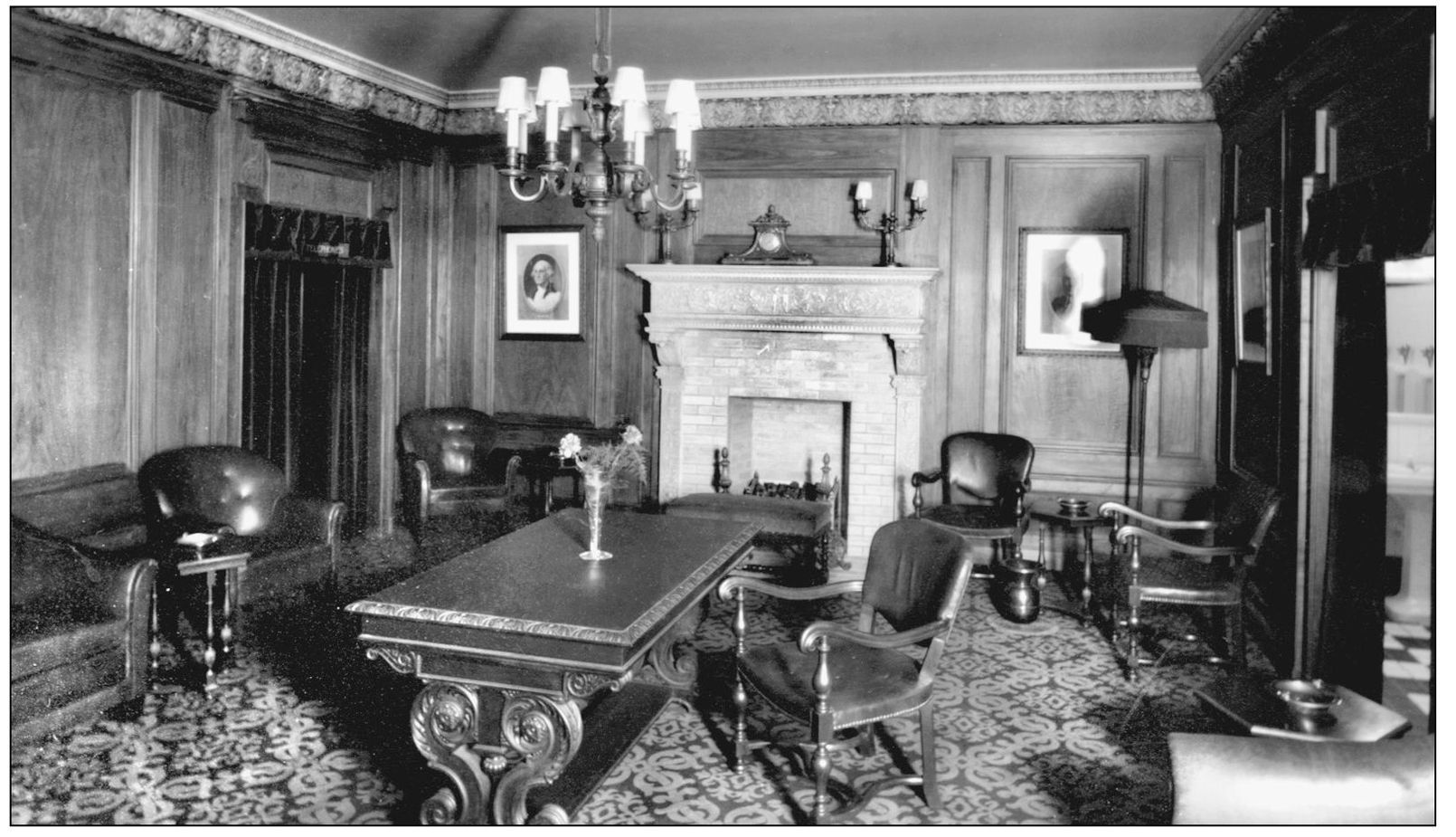

Men were asked not to smoke their cigars inside the theater in 1930. Like the exclusive clubs around town, the Albee provided smoking lounges for both men and women. A gas fireplace warmed the gentlemen’s smoking room, and the walls were paneled in French walnut and adorned with English prints. Note the ashtray on every table and the spittoon on the floor to the right. (Photograph by W. T. Myers and Company; courtesy of Bill Myers.)

Muted shades of green and gold gave the women’s lounge an elegant and comfortable, yet homey, feel. Mezzotints of old French paintings bedecked the walls. Women could chat, smoke, and read between the Albee’s shows at the intimate marble-top table while relaxing in the gentle warmth of the gas fireplace. (Photograph by W. T. Myers and Company; courtesy of Bill Myers.)

The audience of 4,000 sank into velour-covered cushioned seats beneath the domed ceiling. Gold, ivory, and silver were the predominant colors in the furniture, walls, floors, draperies, crystal chandeliers, and expensive silver-framed mirrors. A giant Wurlitzer organ was located at the left side of the orchestra pit. By the early 1970s, many of the downtown theaters had been razed. After an unsuccessful Save the Albee campaign, it too was demolished in 1977. (Photograph by W. T. Myers and Company; courtesy of Bill Myers.)

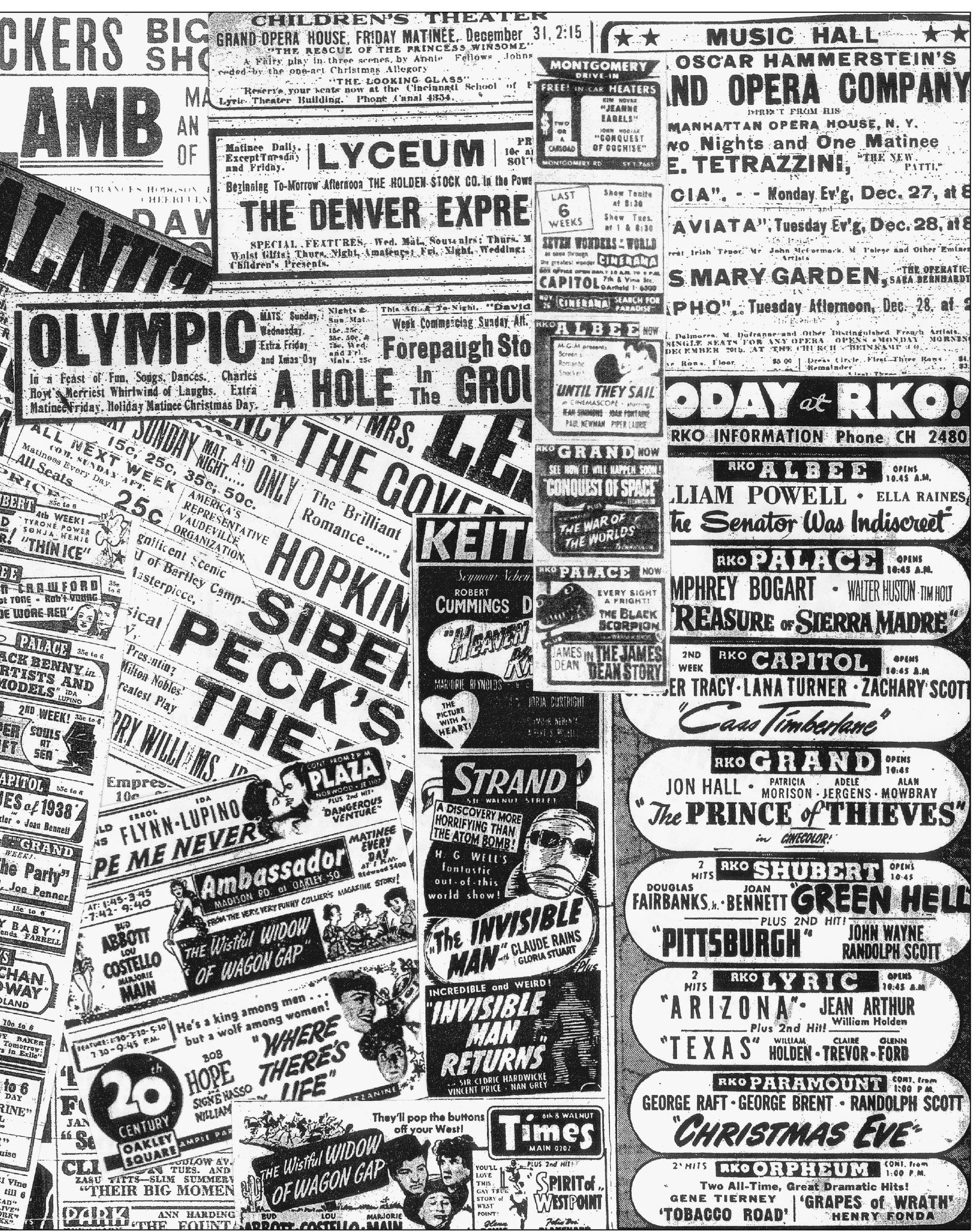

With the dizzying array of entertainment choices in the Queen City, Cincinnatians were never without someplace to go. (Courtesy of the Cincinnati Post.)

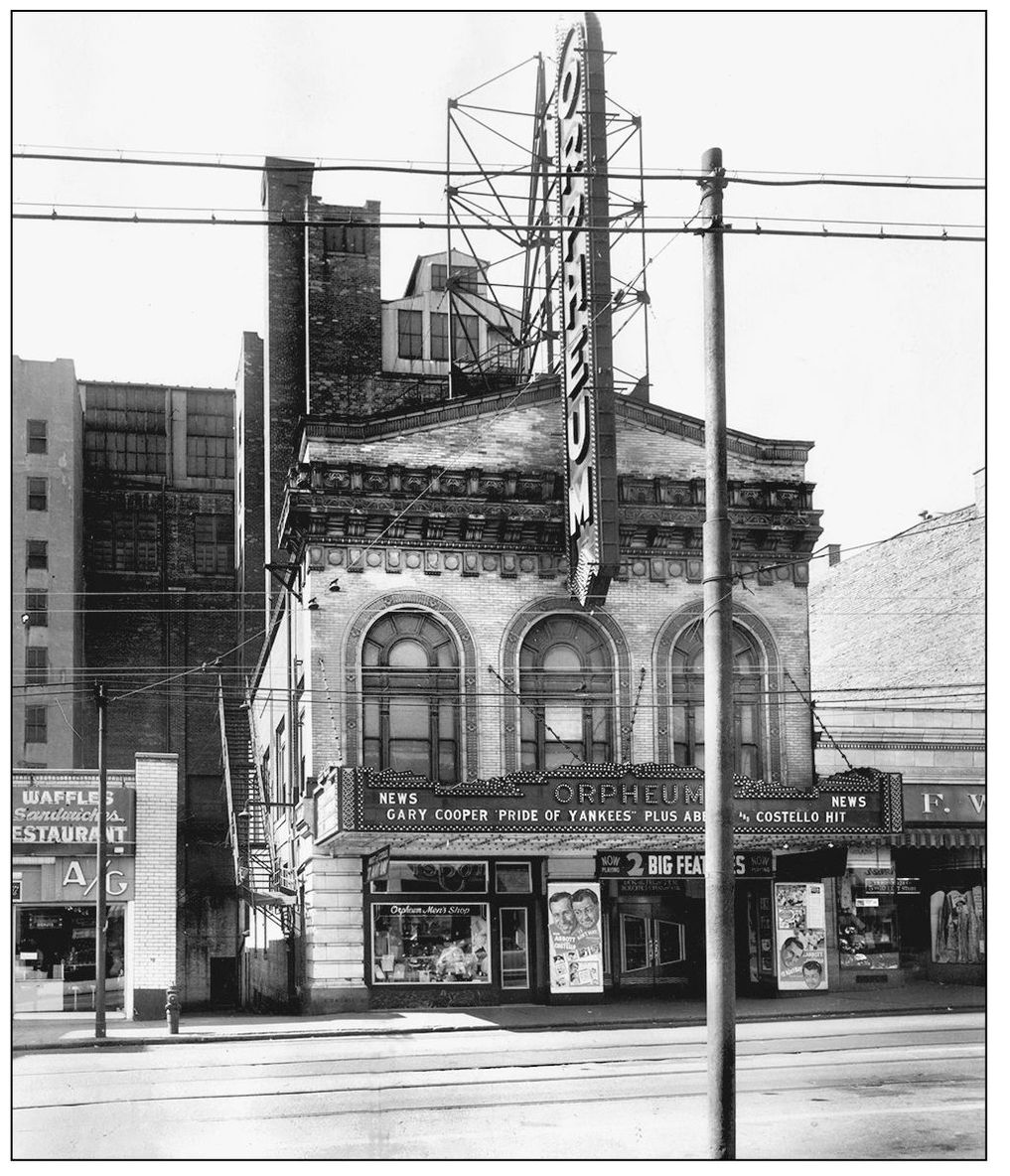

Cincinnati’s first suburban theater was the Orpheum, opened in December 1909. Located at 941 East McMillan Street near Peebles Corner, it showed vaudeville and first-run silent pictures. In 1940, the theater was remodeled with new seats and modern equipment. This week in 1943, the Orpheum presented Pride of the Yankees and Abbot and Costello in It Ain’t Hay. In July 1952, the theater was closed and later torn down. (Photograph by Ben Rosen; courtesy of www.cincinnatihistory.com.)

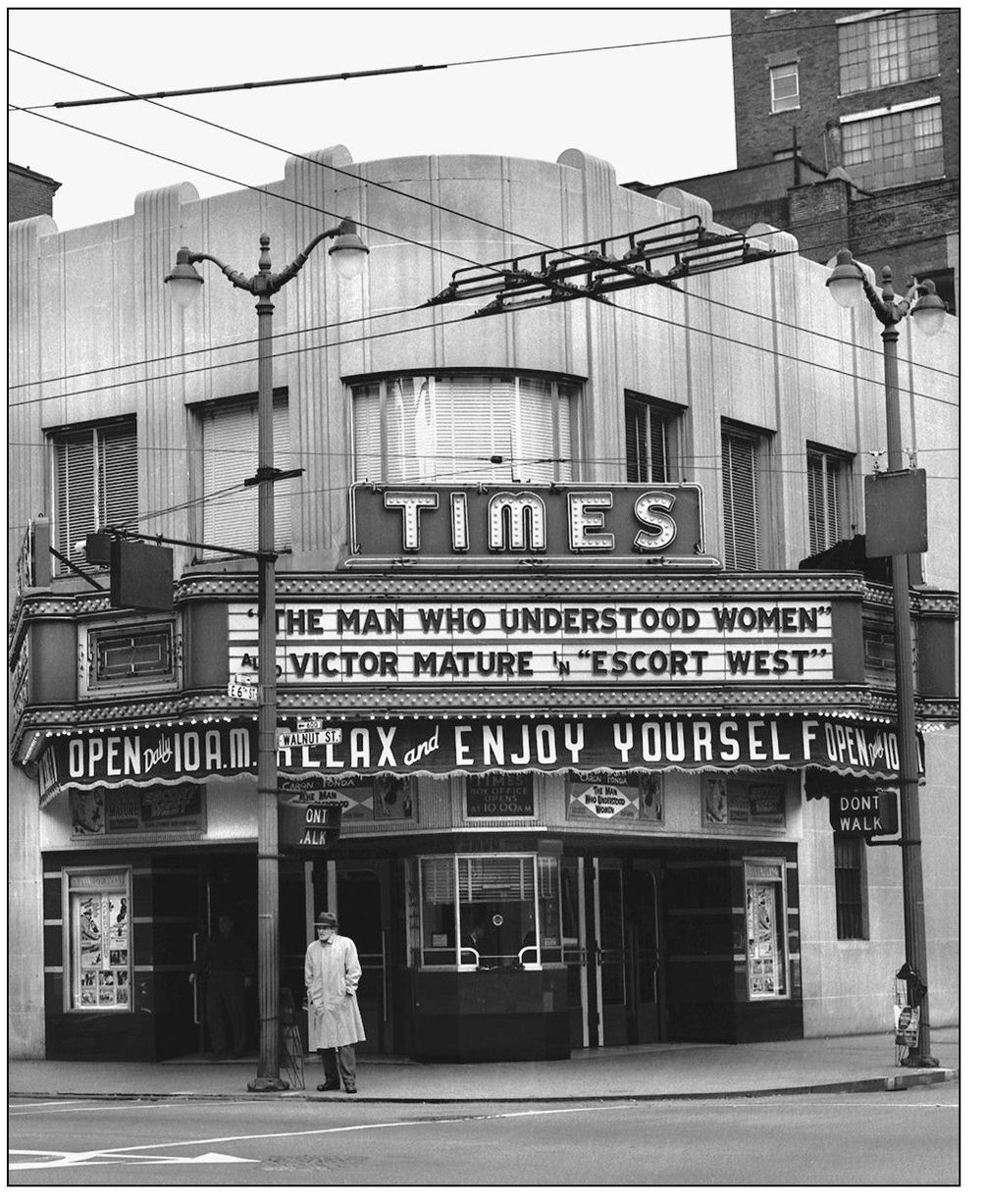

The Times-Star building, a downtown landmark at Sixth and Walnut for 40 years, was razed in 1939. The new one-story Times Theater was built in its place and opened in the fall of 1940. In 1959, this small 636-seat Art Deco theater was showing the comedy The Man Who Understood Women, starring Henry Fonda, and Escort West, with Victor Mature. (Photograph by Ben Rosen; courtesy of www.cincinnatihistory.com.)

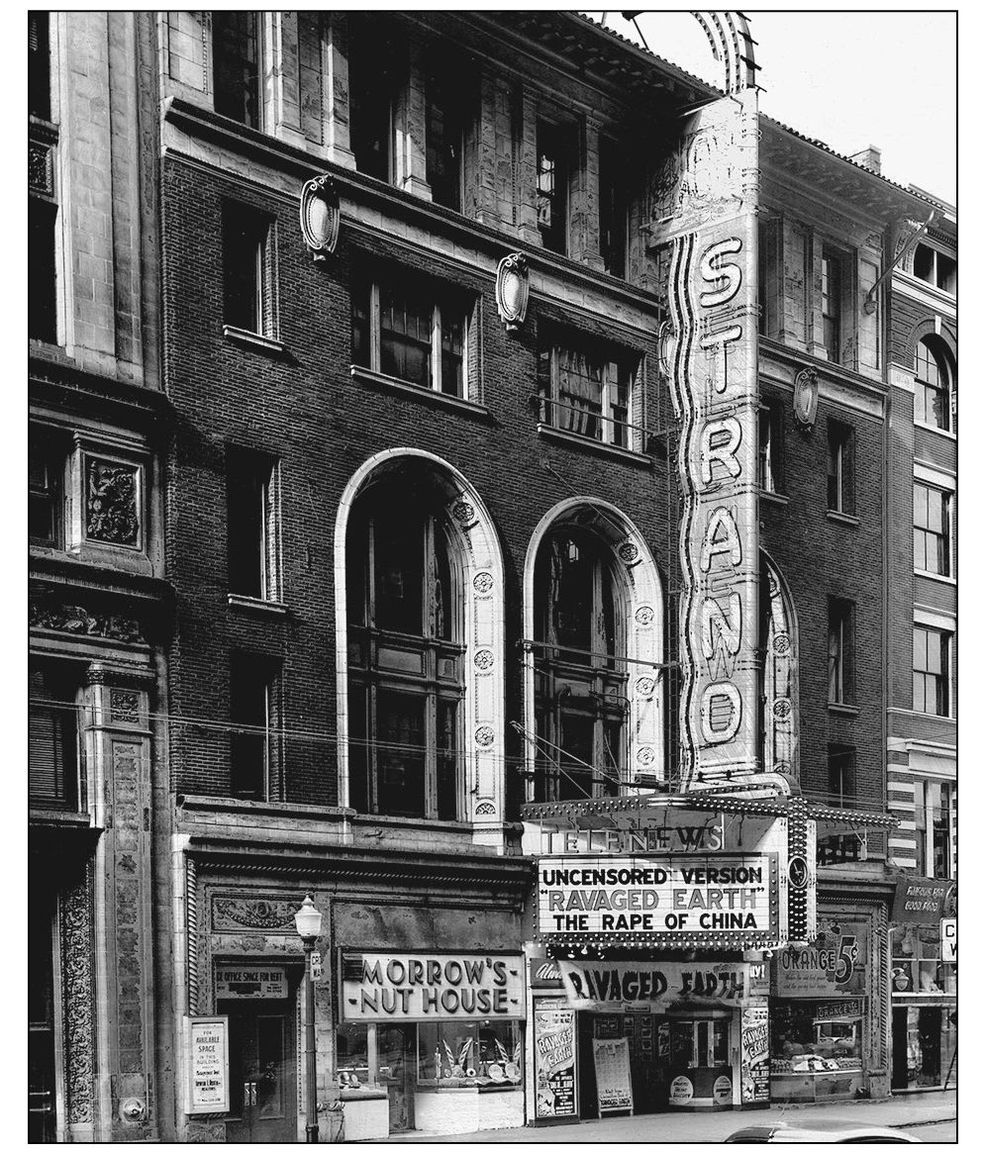

“Ladies and Gentlemen, Burlesque Revolutionized!” The Gayety Burlesque Theater opened at 529 Walnut Street in 1913 with “clean” shows from the Columbia burlesque circuit. In 1914, it became the Strand movie house and burlesque moved to the Olympic. The Strand closed in 1950, soon after the Z-grade film The Ravaged Earth appeared. It fell to the wrecker’s ball in February 1951 to allow for a 200-car parking lot. (Photograph by Ben Rosen; courtesy of www.cincinnatihistory.com.)

The diminutive Olympic Theater opened as a vaudeville house at 118 East Seventh Street between Main and Walnut in 1906. In 1914, it began featuring the burlesque shows from the former Gayety. It closed in 1930. The Aronoff Center stands there today. (Courtesy of www.cincinnativiews.net.)

Almost every neighborhood in Cincinnati contained a theater in the first half of the 20th century. Most closed after the emergence of television’s free entertainment. Price Hill had four theaters: the Sunset, the Glenway, the Western Plaza, and the Warsaw Theater at Warsaw and Wells. The Warsaw opened in 1911 and, as shown in this view, ran silent flicker shows starring Mary Pickford and Tom Mix to spellbound Price Hill crowds. (Courtesy of the Price Hill Historical Society.)

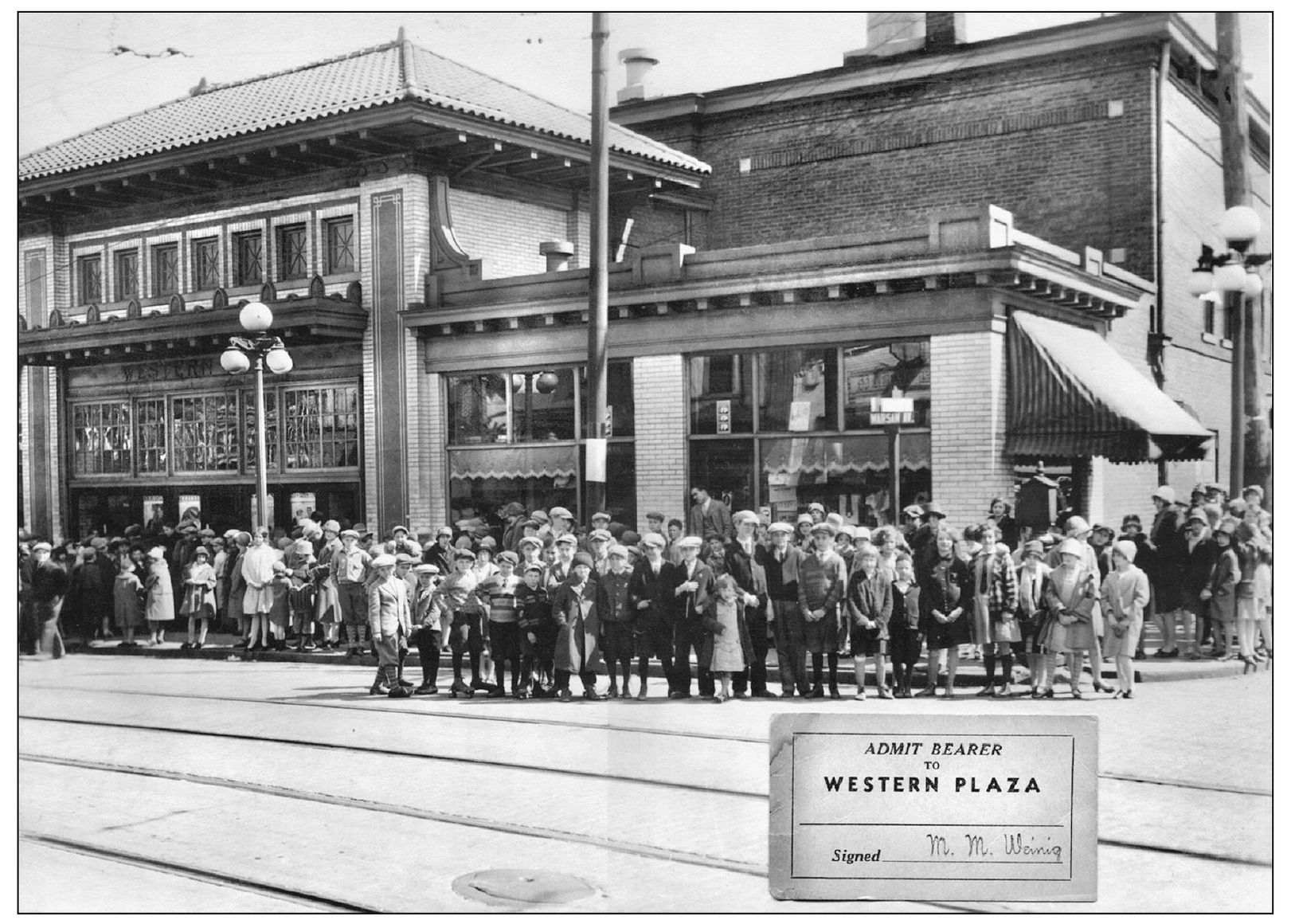

On the left side of this 1924 scene, the Western Plaza Theater at Warsaw and Enright offers a free showing of Robin Hood, starring Douglas Fairbanks, for Price Hill schoolchildren. The theater was demolished in 1965. (Courtesy of the Price Hill Historical Society.)

Seen here in 1952, the Empire Theater movie house opened at 1521 Vine Street in 1909. It was remodeled in 1936 and closed in the 1960s. The theater slowly deteriorated until 2004, when a concert promoter secured a city loan with plans for renovations. The promoter took the money and fled to New York, where he was apprehended by the FBI. The theater’s roof soon collapsed, and the building was bulldozed. (Photograph by Ben Rosen; courtesy of www.cincinnatihistory.com.)

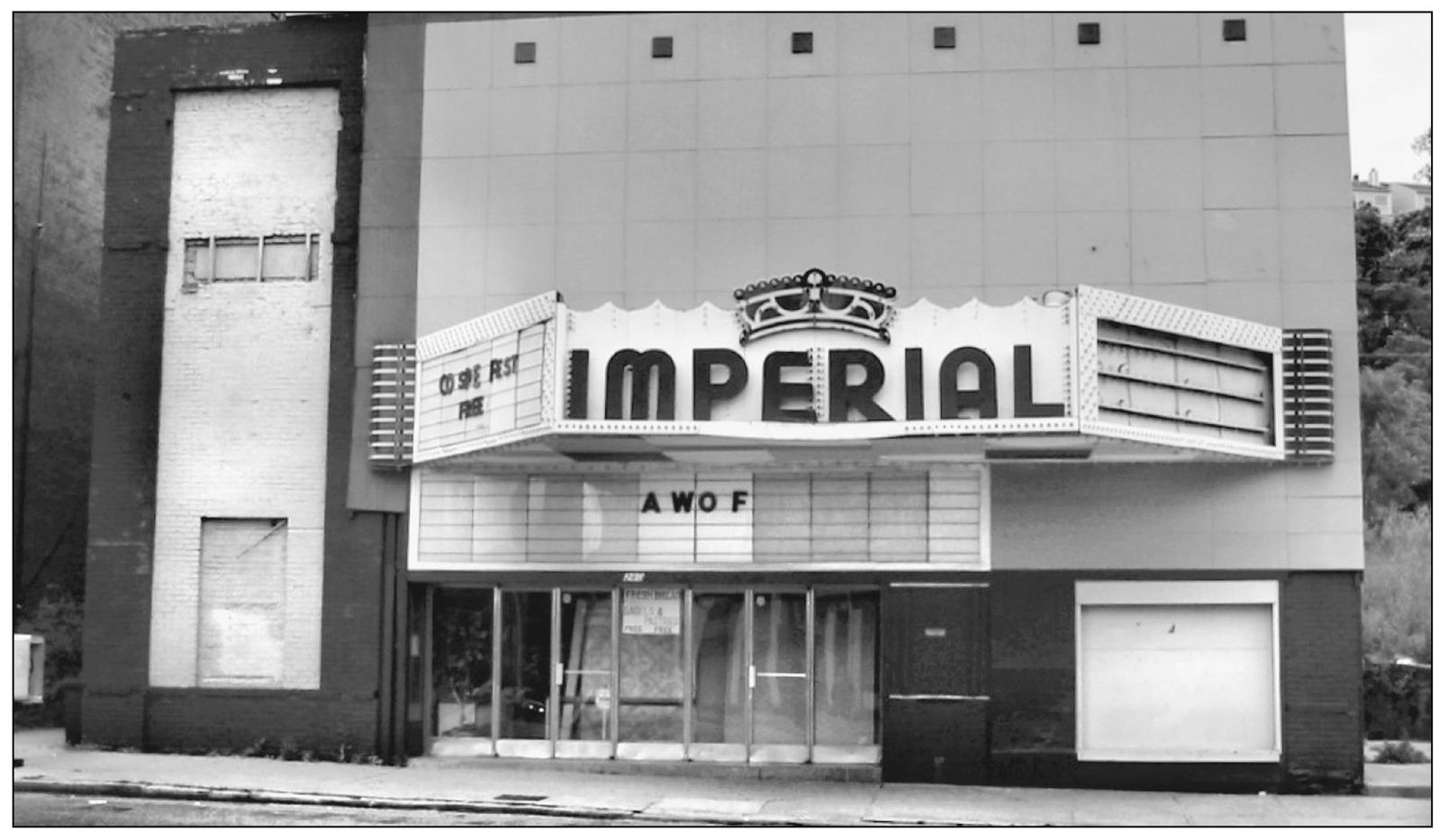

In the neighborhood of Mohawk, at 282 West McMicken Avenue, stands the old Imperial Theater. In the 1960s, it began showing X-rated “sexploitation” films, thus becoming a grindhouse theater, popularized by New York’s Times Square burlesque houses that showed movies between strip shows. The Imperial later became the Imperial Follies strip joint and, in the 1970s, was converted into a neighborhood church. It is closed most of the time today.

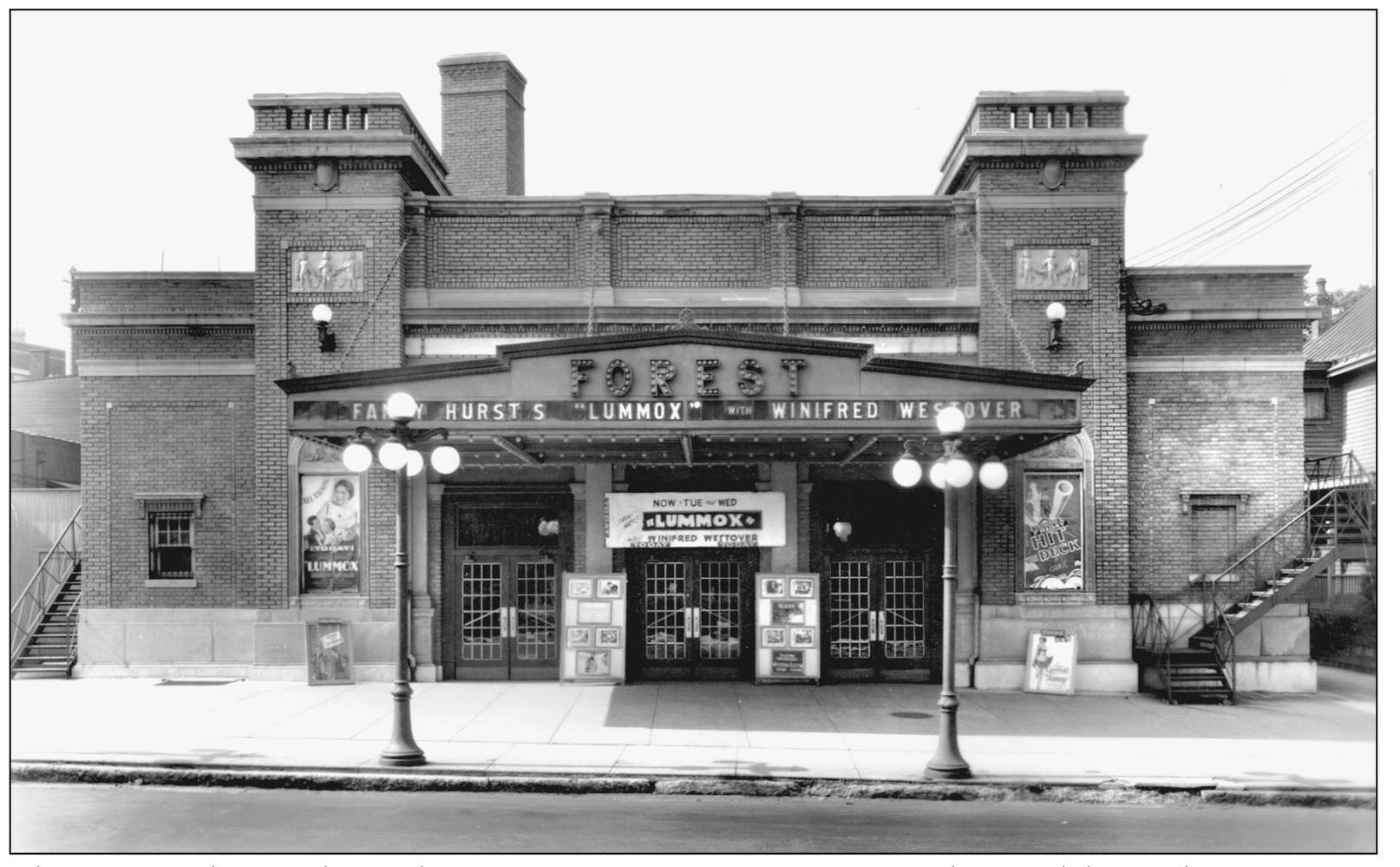

The Forest Theater, located on 671 Forest Avenue, entertained Avondale residents for over three decades. Tickets were 45¢ in the 1950s, and most audience members chose the floor seats over the two balconies. On weekends the Forest was a popular spot for the under-16 crowd, who took advantage of their reduced 20¢ admission. It closed in the 1960s and was later demolished. Showing this week in 1930 were Lummox and Hit the Deck. (Photograph by W. T. Myers and Company; courtesy of Bill Myers.)

The Ridge Theater opened on Montgomery Road in Pleasant Ridge in 1941. Only 20 years later, it closed. (Courtesy of the Arthur Glos Collection, Pleasant Ridge Branch of the Public Library of Cincinnati and Hamilton County.)

Second-run movie houses were situated in suburbs throughout the community, like the cozy and elegant Bond Theater at 4906 Reading Road. The theater closed after the 1950s, eventually becoming a synagogue. On screen this week in 1942 was Cecil B. DeMille’s Reap the Wild Wind, starring John Wayne and Paulette Goddard. (Photograph by Ben Rosen; courtesy of www.cincinnatihistory.com.)

The Nordland, at 2621 Vine Street in Corryville, opened as a vaudeville house around 1905. The theater eventually closed in 1955 due to competition from television, as seen in this 1957 photograph. It was remodeled and reopened in November 1960, showing current German films to an audience of 900. The Nordland later became Bogart’s and today continues to feature music shows of all kinds. (Photograph by Ben Rosen; courtesy of www.cincinnatihistory.com.)

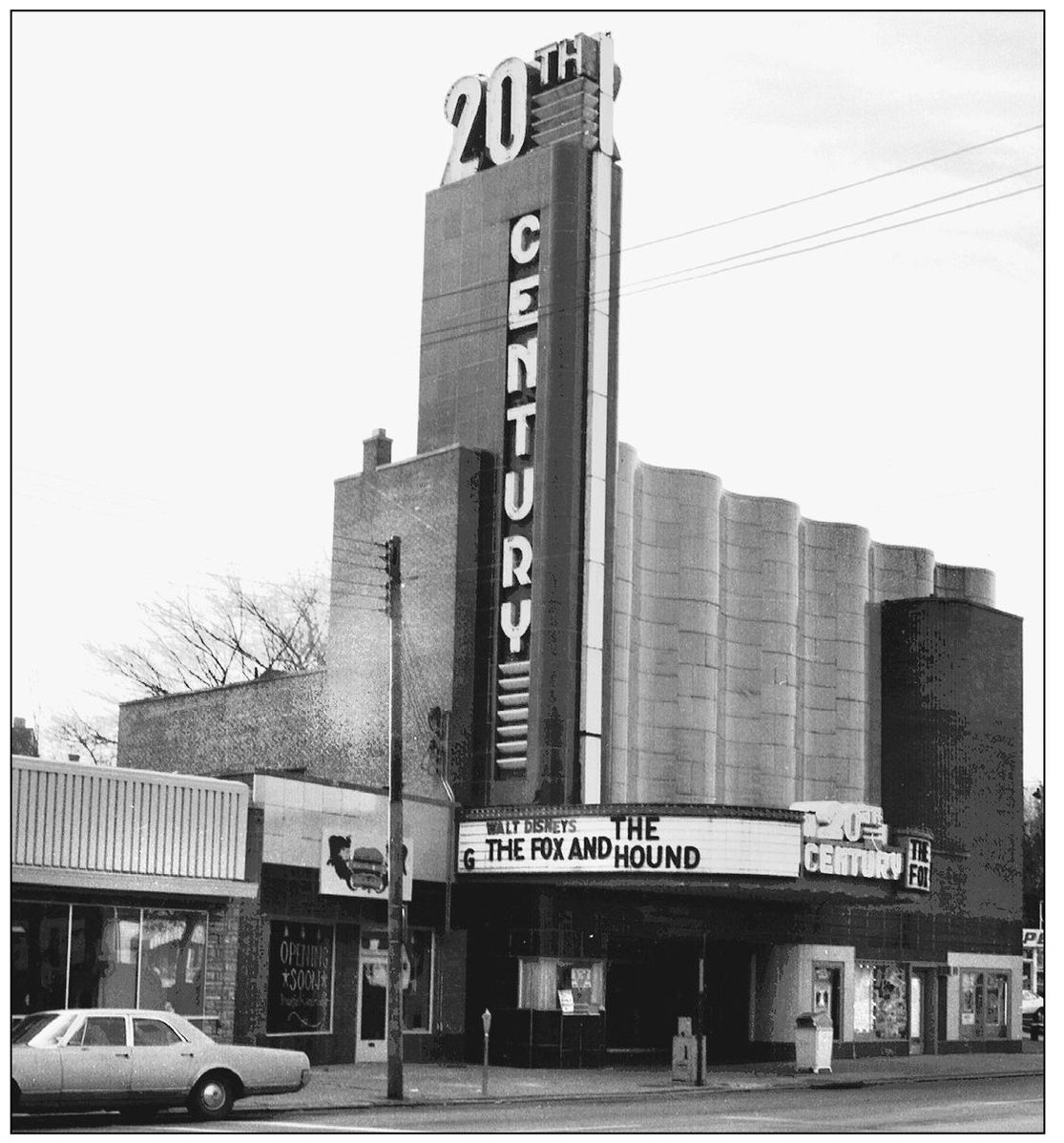

The premiere at the 20th Century Theater in Oakley was Blood and Sand on August 1, 1941. This post–Art Deco movie house had excellent acoustics and offered free valet parking. It closed two years after it showed Walt Disney’s The Fox and the Hound in 1981. In 1997, 20th Century Productions bought the old theater and converted it into a banquet and concert hall, which still operates successfully today. (Photograph by Ben Rosen; courtesy of www.cincinnatihistory.com.)

The 1,400-seat Nowland’s Opera House opened at Seventh and Washington in Covington in 1883. It was renamed the Hippodrome in 1912. Local theater mogul L. B. Wilson bought the theater in 1928 and remodeled it to show third-run movies. A contest winner named it the Broadway in 1930, and it closed in the 1950s to make way for a parking lot. This week in 1930, Covington audiences enjoyed Ladies Love Brutes. (Courtesy of the Kenton County Public Library.)

The Madison Theater, at 728 Madison in downtown Covington, first opened in 1912 as a movie house. Thousands of Covington residents would visit the Madison, as they did in 1946 when Bette Davis starred in Deception. After the 1950s, Madison Avenue began a slow decline, and the theater closed in 1977. In 2000, a developer poured millions into refurbishment and opened the new Madison Theater in 2001 as a concert hall. (Courtesy of the Kenton County Public Library.)

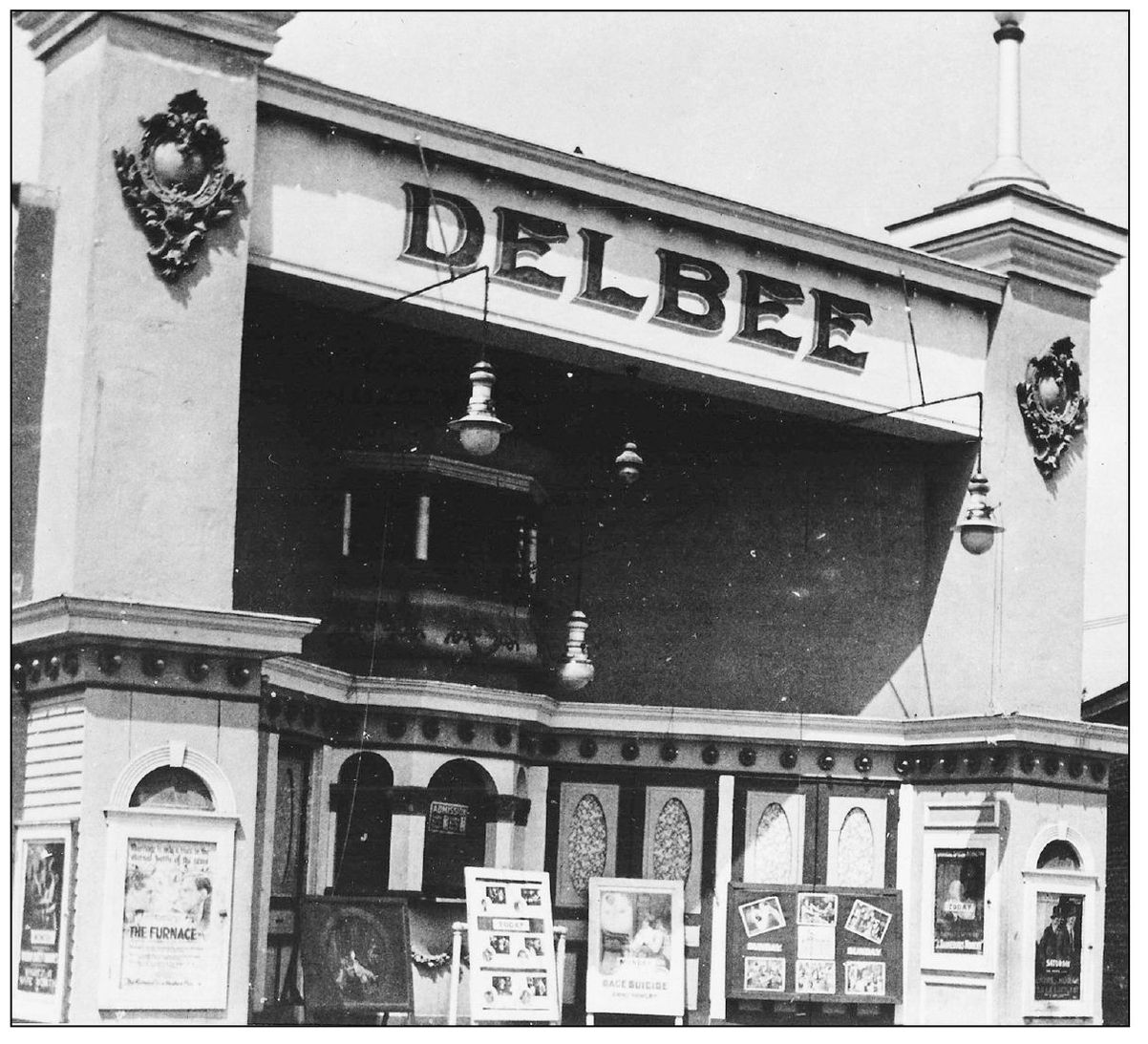

Residents of Latonia, the southernmost suburb of Covington, went to the Delbee Theater, at Fortieth and Decoursey, in the early 20th century for hand-wound silent films. This week in 1920 the Delbee featured the drama The Furnace, starring Agnes Ayers and Jerome Patrick. (Courtesy of the Kenton County Public Library.)

Although casinos inhabited nearly every street in Newport, several theaters were located around town as well, including the Strand on Monmouth between Eighth and Ninth Streets. Here, in 1945, it presents the musical comedy Stork Club, with Betty Hutton. (Photograph by Ben Rosen; courtesy of www.cincinnatihistory.com.)