Two

BROTHER, CAN YOU SPARE A DRINK?

Cincinnati’s beer heritage can be traced to the influx of German immigrants in the 19th century. The Germans brought their beer, prompting the building of breweries all over town, followed by saloons. By 1880, there were 1,837 taverns operating in Cincinnati. On Vine Street alone, especially near Fifth and Vine’s “Nasty Corner,” an incredible 113 saloons stood.

The Temperance movement spanned from 1840 to 1918, and its members campaigned in the 1880s for “blue laws,” successfully closing saloons on Sundays. By 1908, excluding Cincinnati and a few other holdouts, 85 percent of Ohio was dry. Five thousand Prohibition advocates presented Congress with a petition in 1913 calling for an amendment prohibiting alcohol. Nineteen states soon banned its manufacture and sale. Some regions went completely dry, but countless saloons kept serving drinks even in the dry states.

Grain during World War I was needed for bread to feed America’s fighting men. President Wilson instituted a total ban on the wartime production of beer in September 1918. Cincinnati’s Mayor Galvin predicted financial ruin from the strict new laws; over $76 million could be lost in city and business revenues.

Congress passed the 18th Amendment on December 18, 1917, and ratified it on January 16, 1919. Banning the manufacture, sale, and transportation of intoxicating liquors, it went into effect exactly one year later. The Volstead Act, passed on October 28, 1919, prohibited any beverage with greater than .5 percent alcohol by volume. On January 16, 1920, the Volstead Act and the 18th Amendment became law. The Temperance movement ended and America went dry.

Hundreds of local taverns closed; their owners took vacations, retired, or moved on to other things. Former saloon keeper Edward Schubert opened a bakery, and Gus Kummer became a department store floor walker. Frank Caldera sold flowers in the new floral shop in the former Ansonia Hotel bar.

Various restaurants experimented with fruit-juice-based drinks, but these proved unpopular. Chicago lawyer and former pharmacist George Remus moved to Cincinnati in 1919 and bought every available whiskey certificate that allowed the bearer to sell alcohol to drug companies. He then bought entire distilleries and set up drug companies and wholesale distributors of medicinal whiskey. All liquor he trafficked was genuine and untainted; in fact, he took pride that his alcohol never poisoned anyone. He started pulling in multimillions and moved into a mansion in Price Hill. Federal agents raided his “Death Valley Farm” operations and distribution center in October 1921, after which he was sent to an Atlanta penitentiary in 1924.

With the help of the bootleggers, speakeasies appeared almost immediately and were hidden everywhere: in riverboats, remote cottages, disguised stores, secret rooms behind false walls, inside downtown buildings and the basements of suburban homes. Most Cincinnati speakeasies lacked atmosphere; they were mainly places to get drunk. Patrons located the “speaks” by word of mouth and whispered a password through a closed door to gain access, hence the term “speakeasy.” In case of trouble, a bell rang. Even if the ring was accidental, patrons dumped their glasses and scrambled for the exits. Liquor prices were high, and the quality was often questionable.

Many local stills were built with lead coils or lead soldering, and bootleggers often cut whiskey with industrial alcohol, creosote, and embalming fluid. Another danger—wood alcohol, or ethanol—was mixed with liquor and would eventually bring blindness or death. The death of Clifford O’Neal on January 20, 1920, was the first local wood-alcohol poisoning. Nationwide alcohol-related death rates peaked in 1927 at nearly 12,000.

Breweries and other companies produced and sold malt syrups, sugar, hops, bottles, and caps for the home brewers. The public library provided instructions. When officials were alerted to one of these operators, agents arrived with their warrants, confiscated the equipment, and destroyed the product. One witness to a bust recalls watching police carry barrels of homemade beer onto the back porch of the house. After they chopped them open with an axe, the beer frothed out and flowed down the porch and two flights of steps, foaming “like a bubble bath.”

Most home-brewing operations and speakeasies were discreet, but some folks built exclusive, private clubs in their basements or top floors. Walls were heavily insulated to deaden the noise of music and dancing. At “Bathtub Gin Row” on Collins Avenue near Mount Lookout, residents made gin and bourbon in their bathtubs and invited their neighbors to drink at 50¢ a shot. One Bond Hill location had a still and sales outlet underneath the backyard of the house, equipped with water, electricity, and sewers all tapped off nearby public utilities. A decorative outdoor fireplace in the center of the backyard provided venting.

One family-run speakeasy operated in a pool hall at the corner of Thirteenth and Clay Streets in Over-the-Rhine. A hidden tube installed behind the bar led to a bedroom on the third floor. A predetermined number of knocks signaled which liquor was to be poured down the tube. The 10-year-old son decoded the knocks and dispensed the liquor. Other knocks signified the presence of a stranger. The booze and tube were then concealed with a throw rug, and schoolbooks were spread on the floor to feign homework.

The Heritage Restaurant on Wooster Pike, also called Kelly’s Roadhouse, was a speakeasy, and the bullet slugs in the walls hinted at a violent past. Mecklenburg Gardens in Clifton had two spigots on the bar. If the spigot was turned one way, it dispensed near beer; if it was turned the other way, out came real beer. The ruse was discovered in a raid on March 29, 1933, almost a week before beer became legal. Sliding panels at Arnold’s Bar downtown hid liquor bottles, and buzzers throughout the restaurant alerted waiters of agents. A second-floor bathtub was used to make gin. The Cotton Club served alcohol in tinted glasses after 2:30 a.m., and Castle Farm in Reading was raided twice in four years.

After the stock market crash of 1929, Prohibition was no longer a hot issue. The concern now was for the unemployed, and Americans favored legalizing beer to help create new jobs. President Roosevelt’s first directive after taking office in March 1933 was to urge Congress to modify the Volstead Act. On April 7, beer containing 3.2 percent alcohol by weight became legal for the first time in 13 years. That day, one elated citizen cried, “Happy days are here again!” Legal beer had returned to the Queen City but was at first only available at downtown restaurants and hotels. Women patronizing the tearooms even enjoyed some beer. Many had never tasted it before and enjoyed it with their lunches, toasting each other’s good health. Tearoom managers witnessed the largest crowds in years.

Supplies quickly ran low, and the few breweries that survived Prohibition had to immediately commence full-scale beer production. These included Bruckmann, Hudepohl, Foss-Schneider, Schaller Brothers, Wiedemann, and Bavarian. They had previously been manufacturing root beer, soft drinks, denatured alcohol, and the much hated near beer.

Repeal ended the speakeasy business, but by March 1933 most were closing anyway. Supply of bootleg alcohol had far exceeded demand, and the unemployed could not afford to buy drinks anyway. Speakeasies began to cut their prices from 50¢ a shot to 25¢. Despite the sudden increase in traffic, they failed to bring in enough business to stay open. Prohibition agents cancelled all raids.

The 18th Amendment was repealed over eight months later, on December 5, 1933. Hard alcohol was finally back. Things were relatively quiet in the Queen City; it was just another Tuesday evening in the reopened nightclubs and few remaining speakeasies. Many folks stayed home and enjoyed cocktails or met with their friends for some bootleg whiskey. Others hit the drugstores to buy alcohol. The surprise came when the bill was rung up. The price had jumped from $1.85 a pint for prescription whiskey to $4. The unsuccessful noble experiment was over, and folks who wanted to enjoy their favorite drinks could do so again legally. This was the first time many had tasted legal spirits. For everyone else, though, repeal was just business as usual.

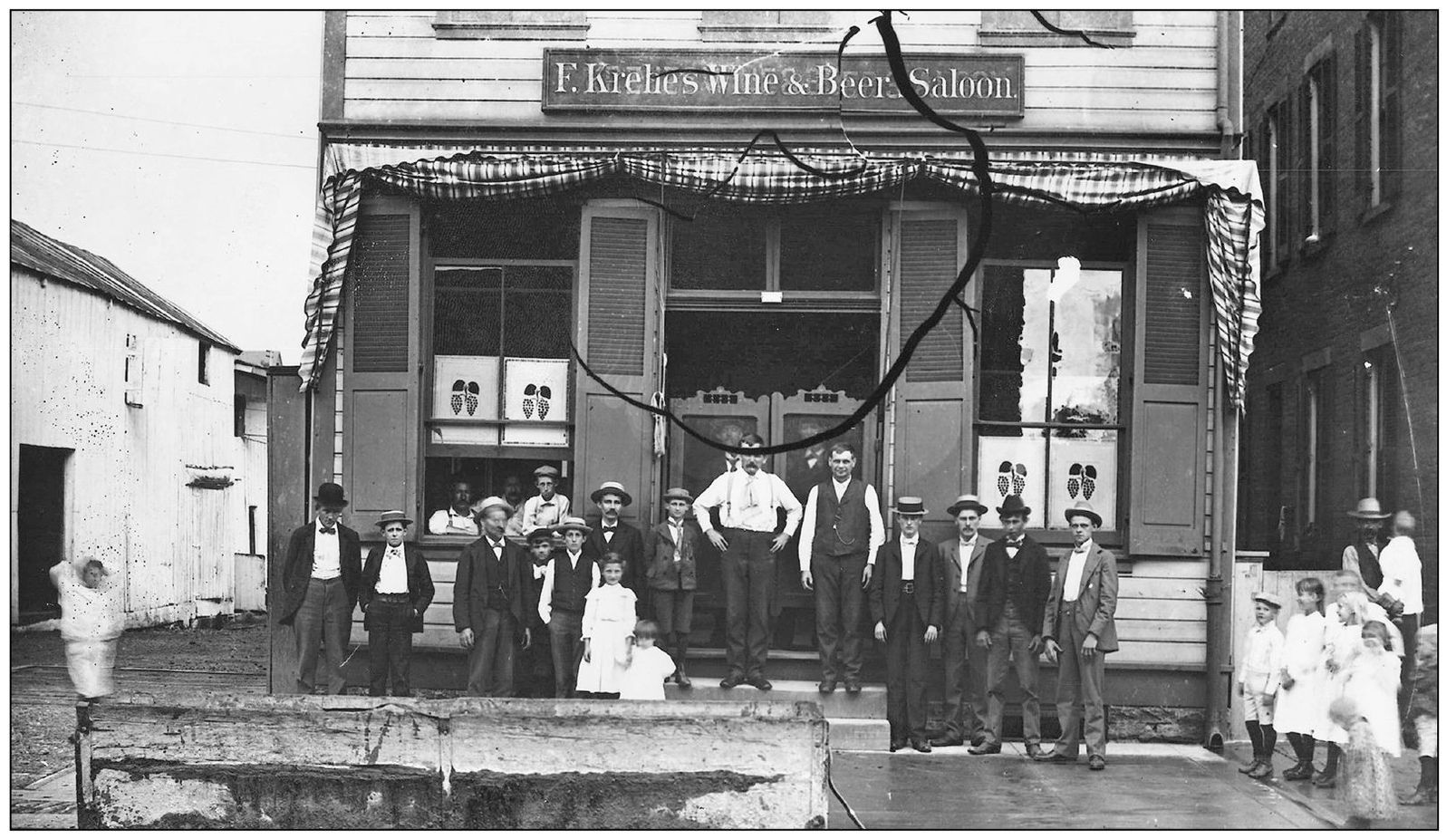

F. Krelie’s Wine and Beer Saloon is a typical early-1900s northern Kentucky tavern. At this time, most were open 24 hours a day, 7 days a week. This was a place, absent of women, where working men could socialize. Here, male clientele pose in front, while most of the children stand politely off to the side. Patrons had to slog through the muddy street to visit F. Krelie’s. (Courtesy of the Kenton County Public Library.)

Alcoholism had become a national concern by the end of the 19th century. Men squandered their entire paychecks on booze and cards in saloons, leaving nothing for their families. Not all saloons, though, were the dens of iniquity sensationalized by Prohibition groups; most were inviting places like Carey’s Café, located at 3832 Glenway Avenue in Price Hill. The first Skyline Chili parlor would open next door to this location in 1949. (Courtesy of www.cincinnativiews.net.)

Almost all saloons, including the Joseph L. Hess Café at Court and Walnut, prepared meals for lunchtime and dinner crowds in pre-Prohibition Cincinnati. Food often came free with the purchase of a drink. (Courtesy of www.cincinnativiews.net.)

The Mount Auburn Garden Restaurant and Billiard Saloon opened on Highland Avenue in 1865. In 1886, bartender Louis Mecklenburg bought the saloon and renamed it Mecklenburg Gardens. It was busted by Prohibition agents on March 29, 1933, for selling beer—just a few days before legalization. The Corryville bar still attracts enthusiasts of traditional German dinners. (Courtesy of www.cincinnativiews.net.)

Foucar’s Café opened at 429 Walnut Street in 1902. The saloon served free roast-beef lunches with purchased drinks. Gold-accented mirrors glittered above the mahogany bar. Local artwork adorned the walls, including Frank Duveneck’s Siesta, showing a nude female resting on a bed. Outraged women protested its presence in the bar, so Foucar took the painting down and donated it to the Cincinnati Art Museum. (Courtesy of www.cincinnativiews.net.)

One room at Foucar’s was the Rathskeller, an 18th-century-style gentlemen’s club. Walls were paneled with black oak. Elk heads festooned the upper walls, and a huge fireplace dominated the far end of the room. Hundreds of men enjoyed dining at the Rathskeller until Prohibition closed it down. (Courtesy of www.cincinnativiews.net.)

Before the appearance of record machines, automatic pianos were always present in taverns. Early-20th-century customers at the Garfield Café, at Eighth and Vine, dropped a nickel into the piano seen at the rear to hear a piccolo and piano duet played from a paper roll. Taverns like the Garfield sold cigars and other sundries in the display cases to the right. (Courtesy of the Cincinnati Historical Library.)

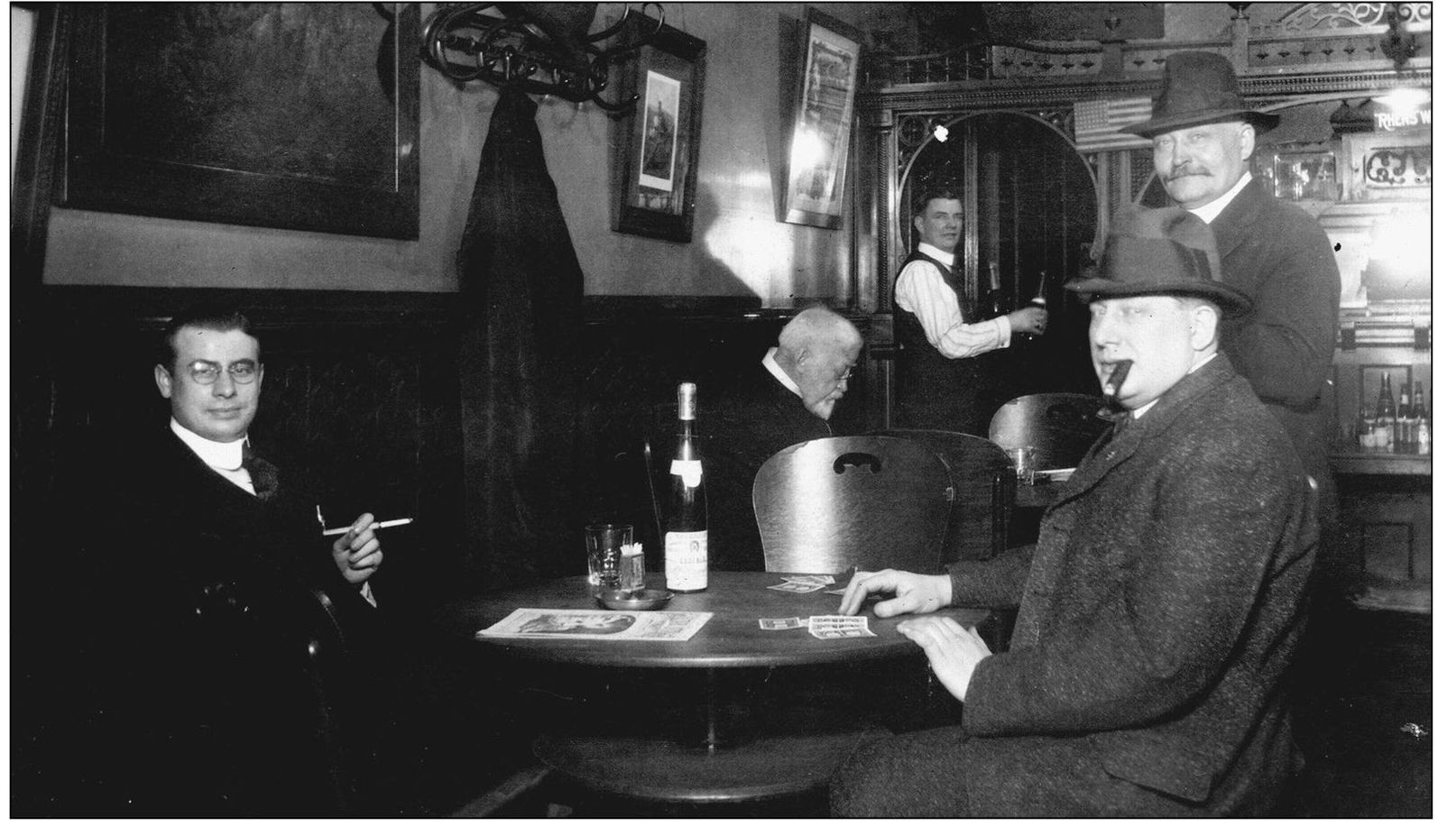

Men were the only clientele at Over-the-Rhine saloons before Prohibition. These establishments gave them a place to drink, seek employment, read newspapers, use stationery and pencils, play cards, shoot pool, bowl, and enjoy their cigars. It was rare when a woman dared step inside, but this likely happened when an irritated wife was seeking her missing husband. (Courtesy of the Cincinnati Historical Society Library.)

Before Prohibition made Cincinnati dry, many folks prepared for the months or years ahead by stockpiling liquor while it was still available, or else face the inevitable bootlegged whiskey. Worth noting in this illustration is the giant “octopus” coal-burning furnace installed in this basement. Most of these furnaces are gone today, having left behind a big concrete ring in the floor, though they remain in a few old buildings. (Courtesy of the Cincinnati Post, January 16, 1920.)

Big parties were thrown on Prohibition Eve so folks could enjoy the last night of legal liquor. Many hosts were forced to dip into their rationed bottles to meet the demands of their guests. (Courtesy of the Cincinnati Post, January 21, 1920.)

Hundreds of saloons had little choice but to close after January 16, 1920, or attempt to stay open selling soft drinks, root beer, or near beer. Proprietors found different jobs, started new businesses, or simply retired. Cliff Langdon’s Café at Peebles Corner was no exception. (Courtesy of www.cincinnativiews.net.)

Before Prohibition, northern Kentucky saloons were more open to admitting blacks than those across the river in Over-the-Rhine. Scenes like this one in Covington would soon become just a blurry memory. (Courtesy of the Cincinnati Historical Society Library.)

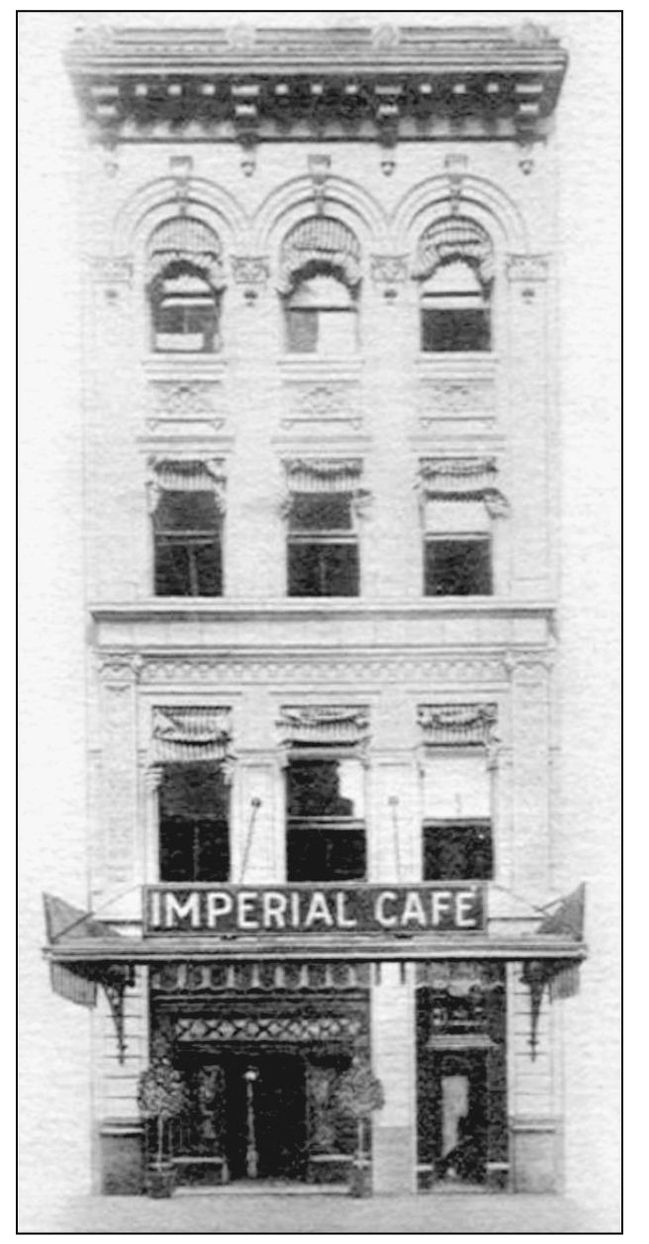

Despite the claim of the “Handsomest Gentleman’s Café in the World,” the Imperial Café, at 520 Vine Street, was located at “Nasty Corner.” Nasty Corner would lose its reputation after 1920. (Courtesy of www.cincinnativiews.net.)

After Prohibition closed gentlemen’s clubs like the Imperial Café, men who wanted to keep drinking had to visit the speakeasies, where women were also invited as long as they had money to spend. (Courtesy of www.cincinnativiews.net.)

Some folks desperate for booze after January 16 were willing to try drinking nearly anything—radiator fluid and gasoline notwithstanding. A constant danger was wood alcohol potentially lurking inside the mystery bottles. Tom, the main character of The Doings of the Duffs, was a steady drinker before Prohibition. These comic strips give us an idea of what daily life was like for Tom, representative of the everyman, when liquor was prohibited. (Courtesy of The Doings of the Duffs, January 25, 1920.)

A typical way to purchase bootleg whiskey was from the shady fellow in a pool hall or on the street. Among the various risks involved was purchasing bottles full of vinegar or some deadly liquid. Seen in the basement of the Duffs’ house is another “octopus” furnace. (Courtesy of The Doings of the Duffs, January 27, 1920.)

“King of the Bootleggers,” George Remus made sure alcohol was available after Prohibition began. His business provided the Queen City with untainted whiskey in the early years of the noble experiment. Alcohol brewed in secret often proved fatal to trusting customers who just wanted a drink, which sometimes resulted in their blindness or death. (Courtesy of Jack Doll, Delhi Historical Society.)

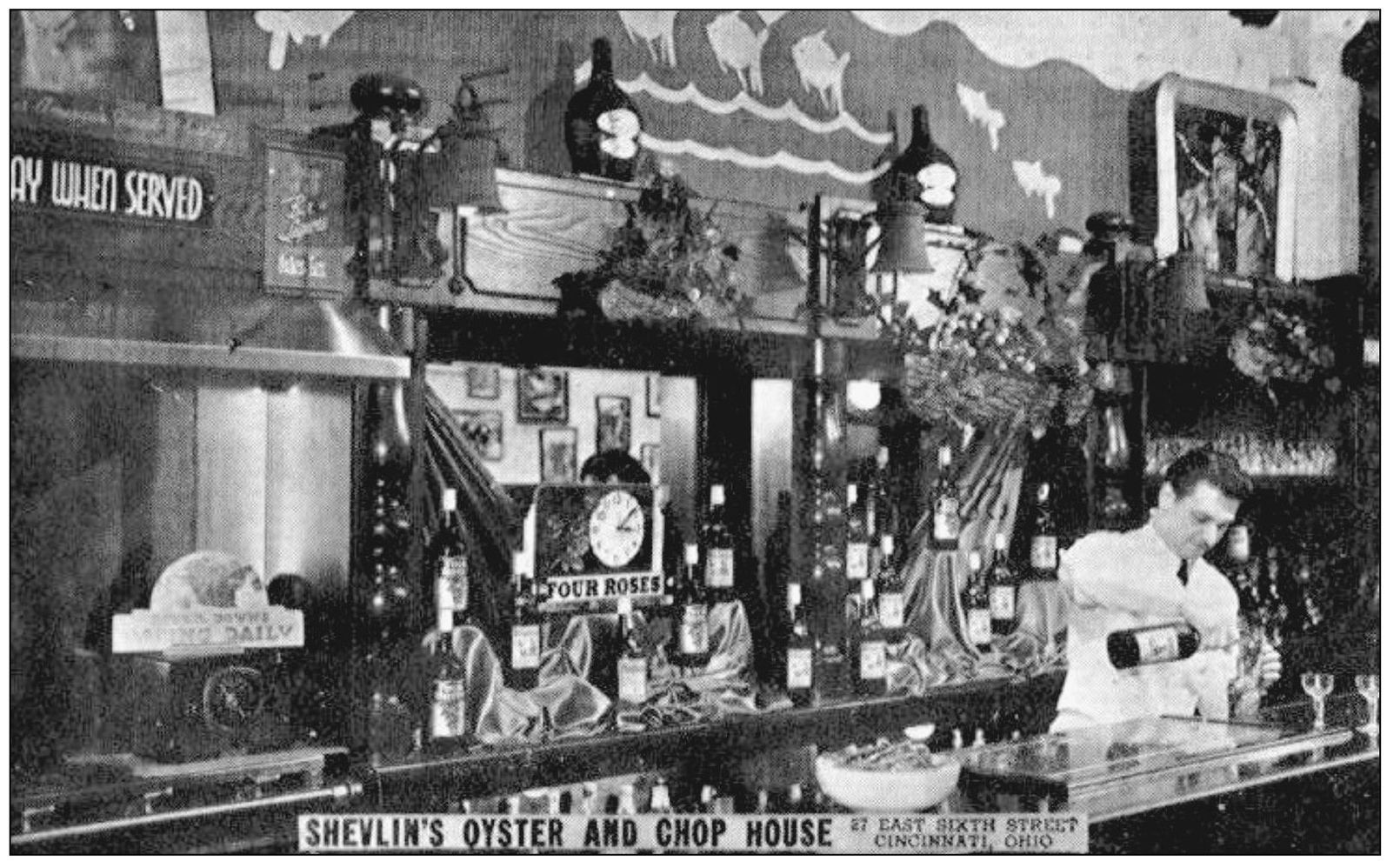

When Prohibition arrived, bartenders stopped pouring drinks at friendly places like Shevlin’s Oyster and Chop House on East Sixth Street. (Courtesy of www.cincinnativiews.net.)

Another Nasty Corner saloon to disappear was the John C. Weber Café at 522 Vine. The Anti-Saloon League and other early-20th-century groups had assumed places like this were immoral; in fact, their members never actually visited the saloons they protested so strongly against. (Courtesy of www.cincinnativiews.net.)

Over-the-Rhine suffered from a reputation of allowing far too many saloons like Harry Welsh’s Café at 1601 Main. As evidenced by this photograph, these taverns were seemingly clean and non-threatening. (Courtesy of www.cincinnativiews.net.)

Real beer made its triumphant return to Cincinnati when the Volstead Act was modified and 3.2 percent alcohol was made legal in April 1933. (Courtesy of the Cincinnati Post, April 7, 1933.)

For 13 years, Prohibition had forced people to rely on bootleggers and home-brewed alcohol to satisfy their cravings for intoxicants. After April 7, it was not long before the bars reopened and the celebratory crowds arrived at the Press Club on Scott Street in Covington. Happy days indeed were here again. (Courtesy of the Kenton County Public Library.)

A positive benefit of repeal was that taxes from alcohol fueled the depressed economy. Bartenders and patrons were happy to roll up their sleeves and help the national effort. (Courtesy of the Cincinnati Post, December 5, 1933.)

Prohibition over, the United States was gradually coming out of the Depression. Money was flowing once again in Cincinnati, and the Mercantile Bar at 410 Walnut Street was remodeled in the modernist, Art Deco style. Customers with pockets full of spending money patronized the Mercantile, one of Walnut Street’s most popular drinking establishments. (Courtesy of www.cincinnativiews.net.)