Five

THE ACTION ACROSS THE RIVER

Live theater, fine dining, movies, and dancing awaited those who stepped out in Cincinnati. Folks could also head across the river to the illegal casinos and brothels in Newport and Covington, where law enforcement was regularly paid off. Prostitution in Newport had roots during the Civil War years, and gambling became a big business around 1900. It was not until Prohibition, though, that Newport became renowned as “Sin City” and “Little Mexico.” By Prohibition’s end, some 44 gambling houses and 14 brothels were operating in Newport, population 30,000. Nine brothels were in business within two blocks of the police station.

The clubs kept Newport’s economy alive; many felt the city would die without it. An estimated one million visited Newport annually in the years before and after World War II. The big clubs operated around the clock. Dancing girls were on the first floor, and gambling was hidden in the back room or upstairs. The ladies were waiting on an upper floor. Taxi drivers got 40 percent kickbacks for bringing in customers. Nobody had to know someone to get in—everyone was invited to gamble. The doorman would even deposit a quarter in the parking meter “on the house.” The front doors were kept wide open so passers-by could eyeball the floor show inside. Hidden steel doors slammed shut when the law was on its way.

All this gambling, especially at Casino Row on York Street, attracted the gangsters in the Cleveland Syndicate who wanted a piece of the action. The Syndicate first focused on Beverly Hills, which burned down in 1936 after owner Peter Schmidt refused to sell. It reopened the next year, renamed the Beverly Hills Country Club. After enduring continued harassment, Schmidt sold Beverly Hills to the Syndicate, which kept it running full tilt until the crackdowns in the 1950s.

The Syndicate next went after the Lookout House on Dixie Highway. This hotspot featured intimate cocktail bars, a restaurant, a showroom, and a casino with big picture windows displaying the panorama of the Cincinnati skyline. The Syndicate allowed owner Jimmy Brink to keep his place after he agreed to work as a front man in 1941. Under the management of the Syndicate, Beverly Hills and the Lookout House quickly became the classiest places in town.

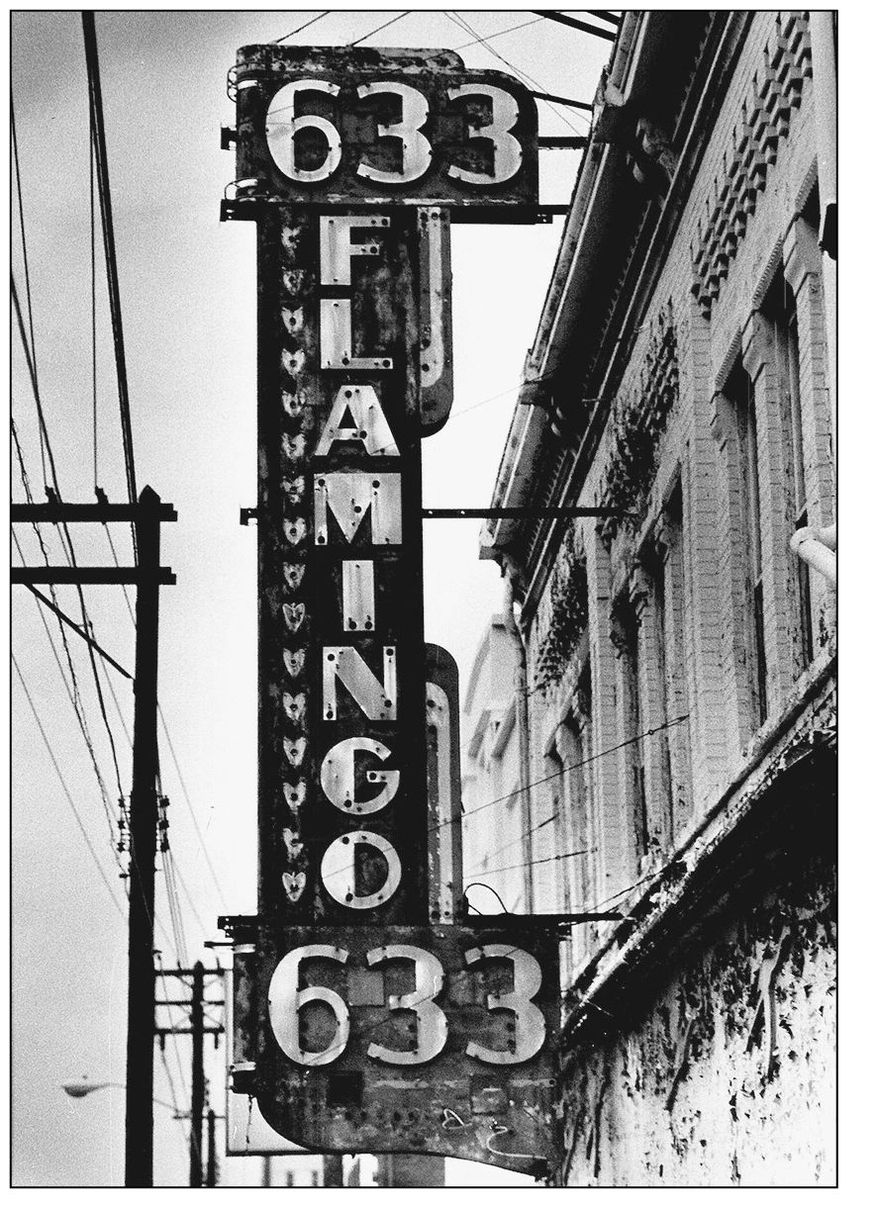

Dice, roulette, blackjack, and bookie services were also available at the Yorkshire Club, where no fewer than 100 patrons would be gambling before noon. A block away was the 633 Flamingo Club, easy to spot with its garish neon sign mounted on the front. The Flamingo had a cafeteria and bar, and an upscale casino in the back. Swivel armchairs let bettors turn from one large blackboard to another to view race results as they were posted. A convenient cashier’s window took bets and paid out winnings to the blue-collar workers who made up the majority of the crowd.

Most of these smaller clubs lacked the elegance and table games at the big houses: the Merchants Club, the Belmont, the Fourth Street Grill, the 316 Club, the 345 Club, the Spotted Calf Café, the Harbor Bar, and the Beacon Inn on Licking Pike. The Golden Horseshoe, the Avenue, and Guys ’n’ Dolls in Wilder only operated for a short time. Monmouth Street had a quite a few clubs including the Mecca and the Kid Able, which later became the Monmouth Cigar. Down the street was the Stork and Slipper, and on the outskirts of Monmouth was the always packed Club Alexandria.

Monmouth’s most notorious club was the Glenn Rendezvous, which opened in 1941 in a three-story building. A concealed elevator carried patrons to the casino and bar on the second floor, and to the bookie on the third. This club degenerated into a “bust-out joint” in its later years, with enticing unbeatable table games, including the dice game Razzle Dazzle. Tito Carinci managed the Glenn Rendezvous in 1957, remodeling it in 1960 into the Tropicana, with the Sapphire Room casino on the second floor. A showroom with strip shows was added on the first floor, and prostitutes were located upstairs.

Wilder Marshal “Big Jim” Harris owned the Stork Club on Monmouth; it was renamed the Silver Slipper in the mid-1950s. Harris also owned the Hi-De-Ho on Licking Pike in Wilder, which was half casino, half brothel. Other clubs in Wilder included the Grandview Gardens Restaurant on Wildrig Street and the nearby Beacon Inn. Covington residents had the Dogpatch, Club Kenton, the Kentucky Club, the Rocket Club, and the Teddy Bear Lounge. Tiny compared to Newport’s, these were all closed by 1952.

Cincinnati’s black gamblers who liked to play the ponies crossed the river to gamble at their favorite clubs: the Copa, Alibi Club, Congo Club, the Rocket, the Sportsman’s, and the Varga and 222 in Covington. Frank “Screw Andrews” Andriola owned the Sportsman’s Club, the center of his gambling and numbers empire, and aspired to control the rest of the black clubs. He took over the Alibi in 1952 and, in 1961, opened his new Sportsman’s Club at Second and York Streets. His club was raided in August by 35 sledgehammer-wielding agents who found an abundance of table games and hidden slot machines. Andrews was arrested and the club shut down.

In 1951, the Syndicate ordered a raid on the Hi-De-Ho Club in Wilder, which they felt was drawing too many customers from the Latin Quarter. State police broke in and destroyed the gaming tables and arrested the girls upstairs. They also found a hidden switch that made a wall swing around, revealing slot machines mounted on the other side. Alerted by Frankfort, Kentucky, politicians, state police raided the Lookout House on March 7, 1952. The club closed soon after, reopening in 1961 without the casino. The Syndicate gave up on this club to focus on its more lucrative locations.

Church and civic leaders started a reform movement in the early 1950s to clean up Newport, and with full community support, the clergy formed the Social Action Committee (SAC). In 1958, the SAC went to the grand jury with testimony and evidence of gambling and prostitution. Jury members found inadequate law enforcement and a need for legal action. More testimony was presented at the 1959 grand jury, but payoffs to the judge ensured the jury would not swing. The grand jury met again in 1960. The SAC presented new testimony to a new jury, and as a result the Newport sheriff was indicted. The gamblers got to the jurors before the trial, and the sheriff was acquitted. The public was outraged by the verdict.

Campbell County businessmen formed the Committee of 500 in 1961. On September 13 of that year, the mayor, city manager, former police chief, four city commissioners, and a score of police officers were indicted. The former police chief and chief detective were found guilty. When former Notre Dame football star George Ratterman ran for county sheriff in 1961, he was framed with prostitute April Flowers and was later found not guilty due to overwhelming evidence and testimony. After the trial, public opinion backlashed against the corruption. Ratterman became sheriff and worked with non-corrupt public officials to close the gambling joints and clean up the city.

After the raid on the Sportsman’s Club, Screw Andrews and his associates were tried in June 1962 and found guilty of running a casino and booking bets. After his five-year sentence, Andrews reopened the Sportsman’s Club with craps and blackjack tables. His tiny new operation lasted until 1968, when federal marshals raided Newport clubs running rigged bingo games. The Syndicate, still operating, owned property in Newport until 1970. When it realized gambling was gone and would not return, it finally left town.

Despite the victories of transforming Sin City, many sexually oriented businesses continued to thrive. In the 1970s, Newport, still infamous for its adult entertainment, suffered from a high crime rate and low property values. In 1978, citizens banded together with city officials to force adult businesses to close. New local ordinances in the early 1980s mandated that strip-club dancers keep certain body parts covered in their acts. Gambling is outlawed and nudity is forbidden in the few gentlemen’s clubs open today, and modern Newport no longer resembles the Sin City of yesterday. Gambling is available at the riverboats in nearby Indiana.

“The Las Vegas of the East,” the Beverly Hills Country Club was the classiest showplace in northern Kentucky. Las Vegas and Hollywood headliners like Jimmy Durante, Milton Berle, Liberace, Steve Lawrence, Eydie Gorme, Buddy Hackett, Carol Channing, Martha Raye, Sid Caeser, Anita Bryant, the Andrews Sisters, Pearl Bailey, Mel Torme, and Tony Bennett performed at Beverly Hills for over three decades. The club also had one of the hottest casinos in town. (Courtesy of www.nkyviews.com.)

Patrons at Beverly Hills listened to Larry Vincent on piano and sipped martinis and champagne while seated around the circular bar. On more than one occasion, ordinary Cincinnatians tipped glasses with Frank Sinatra between his stage performances and his trips into the casino. (Courtesy of www.nkyviews.com.)

Dinner was served at 6:00 in the Trianon Room, and at 8:00 the stage acts went on, playing for an hour and a half. Bingo games came next. At 10:00, the floor opened up so everyone could dance to the Gardner Benedict Orchestra. The headline act went back on stage for the 11:30 performance. After the final curtain call, the orchestra played more dance music until 2:00 a.m. (Courtesy of the Dave Horn Collection.)

Beverly Hills served affordable, great-tasting four-course American-style dinners. This menu, signed by Ozzie Nelson and Harriet Hilliard of radio and television’s Ozzie and Harriet, dates to 1940, a time when frog legs appeared on the menu of every fine dining establishment. (Courtesy of www.nkyviews.com.)

Crowds expected fun-filled evenings at Beverly Hills. When the show began, a line of chorus girls in frilly costumes high-kicked to the cancan. A novelty act came next, followed by a comedian, singer, or dance team and an artful ballet. At last, the headliner performed for an hour. During the finale, the chorus girls danced while the house performer sang showtunes to the thunderous applause of the audience. (Courtesy of the Dave Horn Collection.)

Transportation historian Earl Clark played lead saxophone in Gardner Benedict’s house orchestra at Beverly Hills during the 1950s. He witnessed firsthand the hundreds of hugely popular stars who appeared on stage and backstage in the club’s golden age. Earl snapped this photograph from his position in the band during the finale of a Mardi Gras–themed show in 1955. Note the smoky haze over the audience. (Photograph by Earl Clark.)

The Beverly Hills chorus girls pose for Earl Clark’s camera before taking the stage for one of their three numbers in 1955. Tacked on the wall behind the girls are photographs of the many famous stars who visited the Southgate nightclub. (Photograph by Earl Clark.)

The Beverly Hills casino was located down the plush, blue-carpeted hallway through oak double doors. This was where roulette dealers spun the big wheels, blackjack players said, “Hit me,” and craps shooters cheered the lucky dice throws. In 1960, the Saturday Evening Post sent a reporter and a photographer carrying a secret camera into Beverly Hills and other clubs. The resulting images offer rare glimpses inside the casinos of Sin City. (Used with permission of the Saturday Evening Post; courtesy of the Dave Horn Collection.)

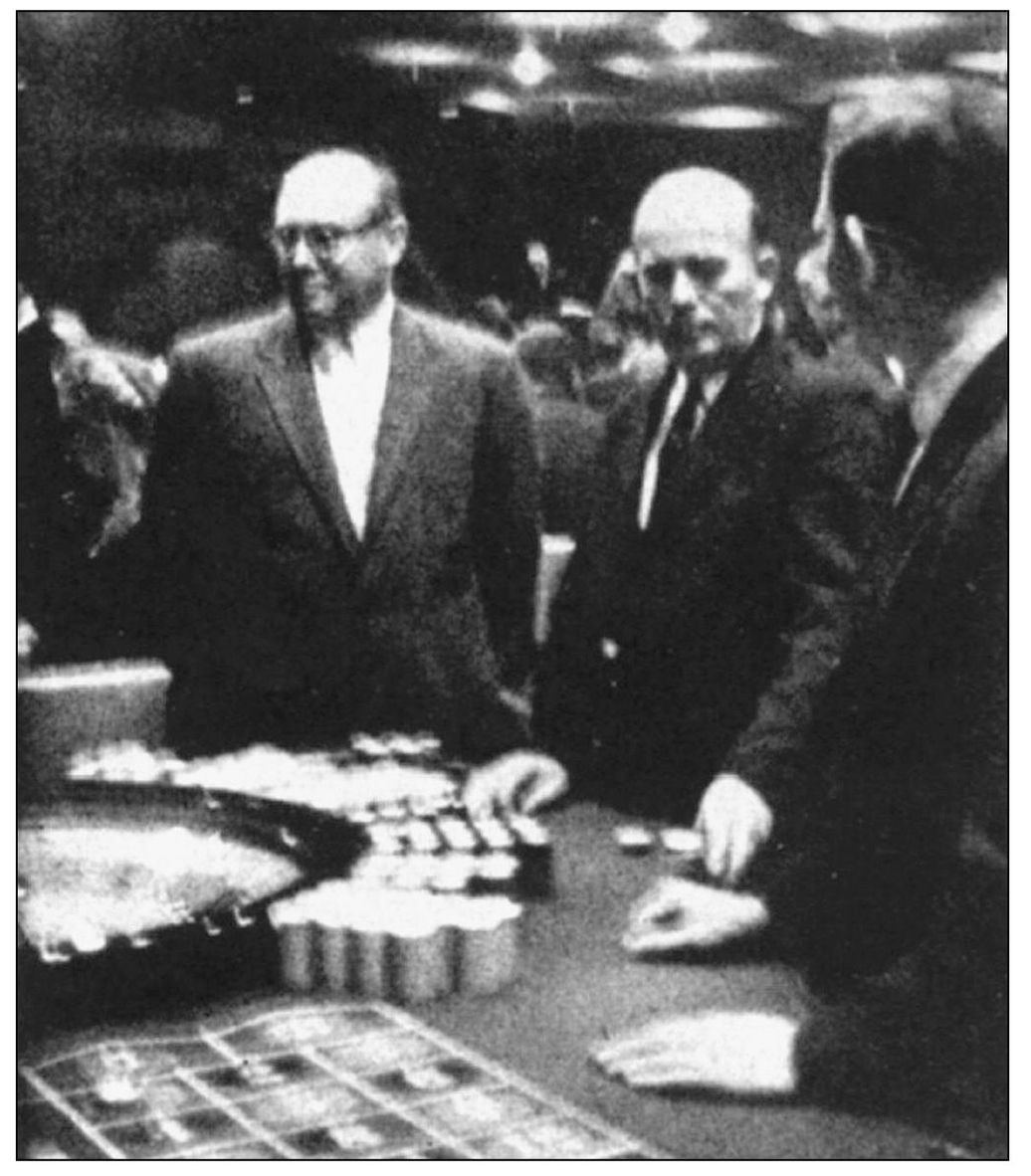

Folks flew in from as far away as New York to watch the floor shows at Beverly Hills and to play the casino games. At the roulette table, the pit boss on the left, known as “Spahny,” keeps a careful eye on the proceedings. (Used with permission of the Saturday Evening Post; courtesy of the Dave Horn Collection.)

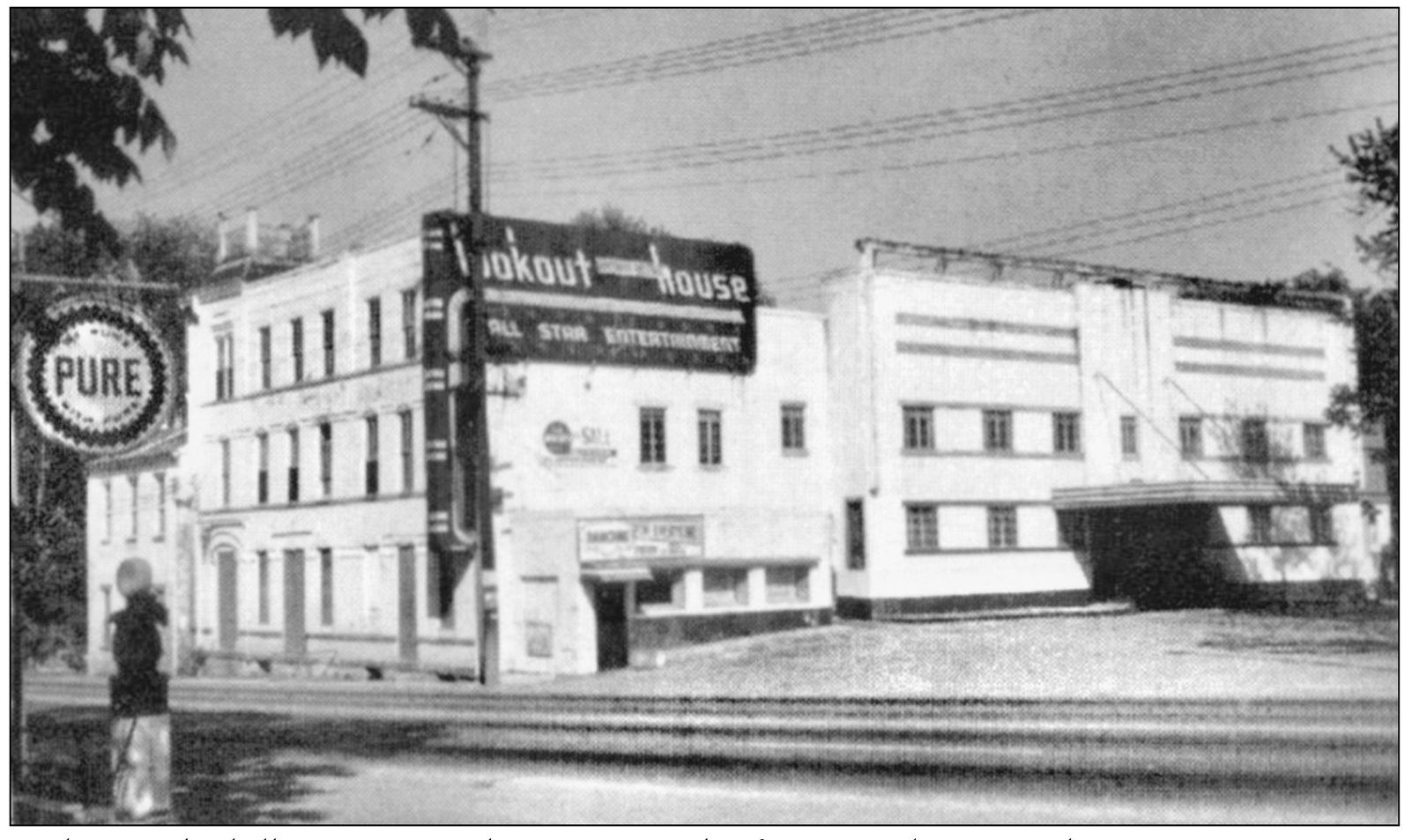

High atop the hill on Dixie Highway, just south of Ben Castleman’s White Horse Restaurant, was Covington’s Lookout House. Restaurant promoter Jimmy Brink purchased the nightclub in 1933 and remodeled it into the “showplace of the nation” with gambling and big-name entertainment. In its later years, the second-floor Little Club featured shows and music seven nights a week beneath a roof that opened up during the summer months. (Courtesy of www.nkyviews.com.)

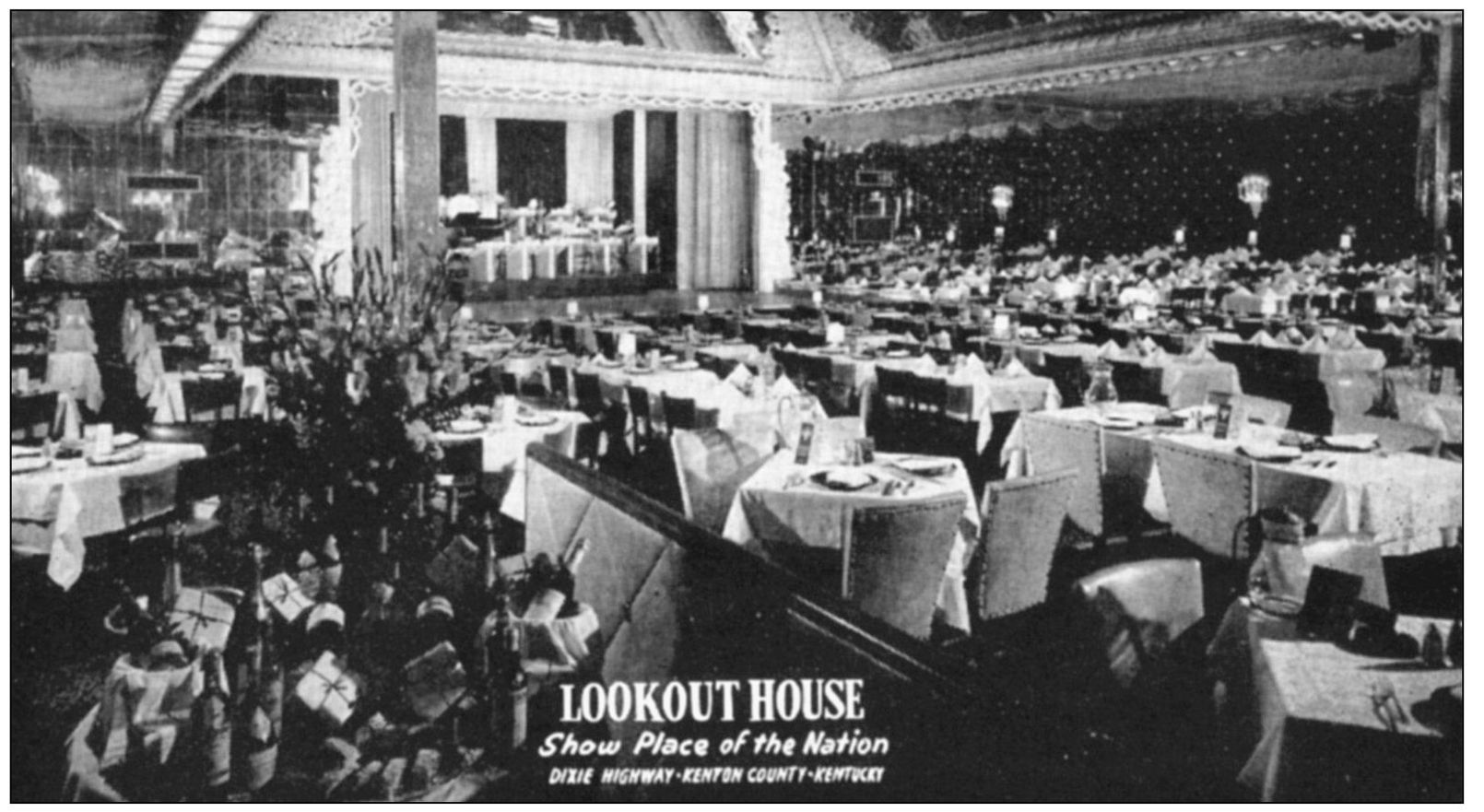

Over 500 guests could dine comfortably in the Casino Room of the Lookout House while enjoying the stage show. It closed after the early-1950s raids but reopened in 1961 minus the casino and stage show and under new management by the Schilling brothers. With a nightclub, 6 new dining rooms, and 15 private party rooms, up to 1,800 folks could enjoy the remodeled Lookout House. (Courtesy of the Dave Horn Collection.)

During stage show intermissions in the 1940s, audience members at the Lookout House enjoyed the tunes of the Fielden Foursome as the group traveled the dining room, entertaining small parties waiting for the main show to return. In 1946, the Foursome included Johnny Fielden on accordion, Bernie Wullkotte on upright bass, Mel Horner on guitar, and Frankie Foltz on vibraphone. The Lookout House burned to the ground in 1973, ending its century-old legacy. (Courtesy of the Cincinnati Musicians Association Archives.)

Out-of-town convention-goers consulted the newspapers to see who was playing where. Whether it was a burlesque show, a Vegas-style nightclub act, or casino gambling, Cincinnati and northern Kentucky could provide it any time of day or night. (Courtesy of the Cincinnati Post.)

One of the largest nightclubs in Newport was the Yorkshire Club, at 518 York Street. The restaurant served good food and drinks at moderate prices. (Courtesy of www.nkyviews.com.)

Adjacent to the Yorkshire’s dining room was one of the busiest casinos in Newport. Visitors were by no means obligated to gamble, but those who did had many excellent ways to lose their wages, like at this blackjack game captured by the Saturday Evening Post photographer. (Used with permission of the Saturday Evening Post; courtesy of the Dave Horn Collection.)

Folks of all ages played the table games at the Yorkshire, as did this woman who was photographed unknowingly during a game of Hazard. (Used with permission of the Saturday Evening Post; courtesy of the Dave Horn Collection.)

Down the street from the Yorkshire was the 633 Flamingo, Newport’s other large club. Gamblers played dice games, roulette, and blackjack in the casino. Enormous blackboards mounted on the back wall listed race results from all major tracks in the country, along with baseball, football, and basketball games. One of the Flamingo Club’s biggest fans was “Sleepout Louie” Levinson, a colorful character famous for his all-night gambling marathons. (Courtesy of the Kenton County Public Library.)

Both Beverly Hills and the Lookout House gave their customers sizzling entertainment. Dozens of other clubs in Newport offered the same types of things, but without the huge headline acts and glitz. Inside an innocuous three-story building on Fourth Street was the Merchants Club, where folks could grab an affordable dinner, play a few table games and slot machines, and participate in a racehorse book. (Courtesy of the Kenton County Public Library.)

While the main draw of the Merchants Club was its casino, it also offered a full cocktail lounge and good food. Many families who had no interest in gambling enjoyed dining in the restaurant. (Courtesy of the Dave Horn Collection.)

The Glenn Schmidt Playtorium, featuring a casino, restaurant, cocktail bar, and bowling alley, opened on Fifth Street in 1951. The casino was moved into the neighboring Snax Bar and became one of Newport’s best-known gambling dens. An underground tunnel connected the Playtorium to the Snax Bar. (Courtesy of www.nkyviews.com.)

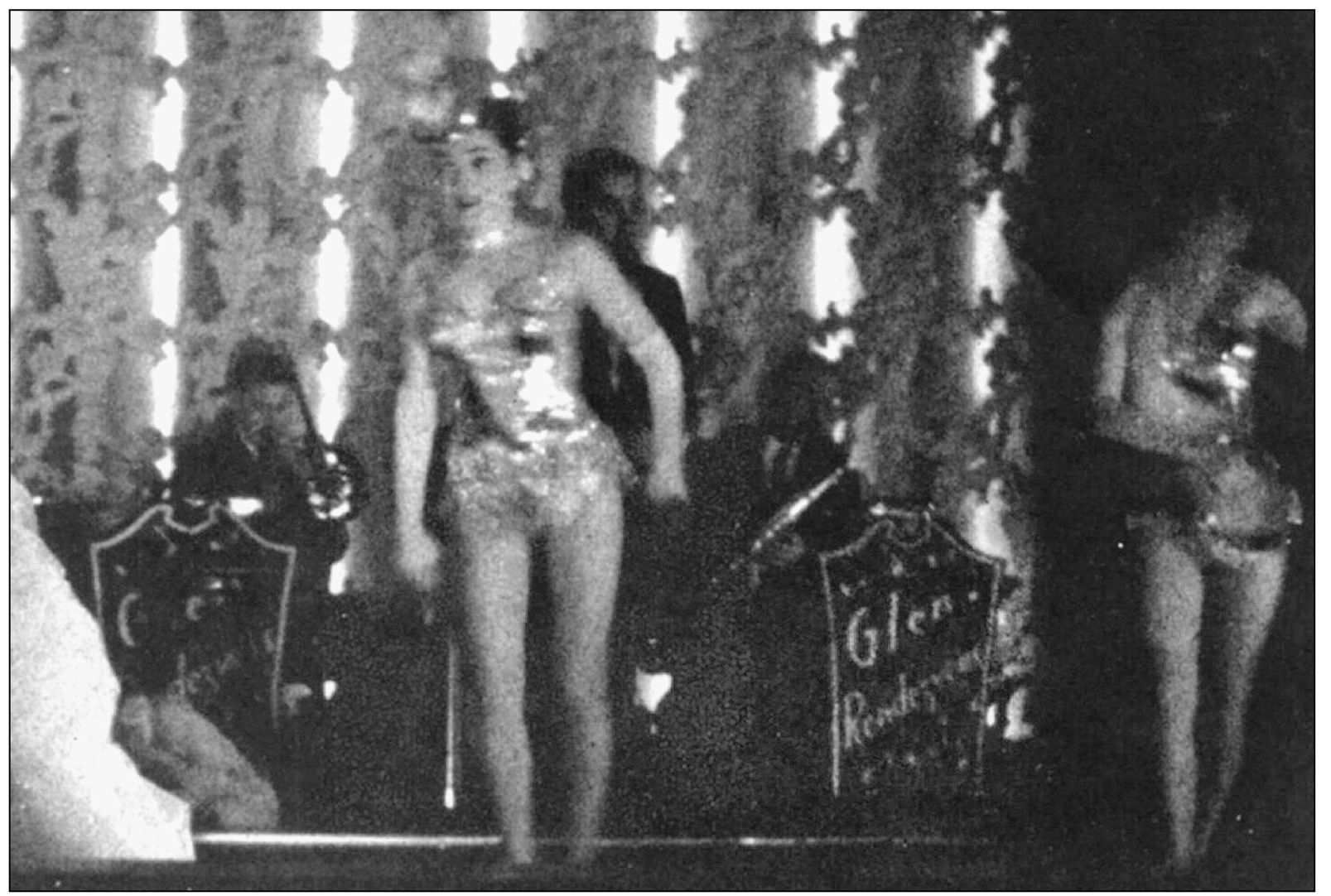

The casino located on the second floor in the Glenn Rendezvous Supper Club catered to the high-rollers. A seven-piece orchestra and floor show entertained in the nightclub, and tuxedoed waiters served first-rate meals to the restaurant guests. In its later years, the casino degenerated into a bust-out joint, and all the stage shows were striptease. If this photographer had been caught, he would have had his camera confiscated and his arms likely broken. (Used with permission of the Saturday Evening Post; courtesy of the Dave Horn Collection.)

Situated on Licking Pike in Newport’s outskirts was Buck Brady’s Primrose Club, formerly the Blue Grass Inn. In 1946, the thriving Primrose began attracting customers from Beverly Hills. After an attempt on Brady’s life, the Syndicate took control of the Primrose, and Brady subsequently retired to Florida. Renaming it the Latin Quarter, the Syndicate outfitted the club with a bigger casino and the chorus line seen in this photograph. (Courtesy of the Kenton County Public Library.)

Patrons who visited the casino at the Latin Quarter had their choice of craps, roulette, blackjack, and a multitude of slot machines. Those who ate at the restaurant received a first-class dining experience. The Syndicate managed several northern Kentucky clubs. Despite the fact that members of the group were thought to be gangsters, they ran their clubs professionally as “determined businessmen,” not as Hollywood-style Godfathers. (Courtesy of the Dave Horn Collection.)

The Kentucky State Police raided the Lookout House in 1952, forcibly ending illegal gambling at the Dixie Highway nightclub. This photograph was taken immediately after the announcement of the raid. The croupier, lower right, has dropped his sticks, and patrons confusedly linger around the craps table wondering what will happen next. (Photograph by the Kentucky State Police; courtesy of the Dave Horn Collection.)

While the Lookout House is raided, a dealer and other employees at the Chuck-a-Luck dice table watch anxiously as detectives gather the irrefutable evidence. Patrons who do not manage to escape are soon placed under arrest. (Photograph by the Kentucky State Police; courtesy of the Dave Horn Collection.)

Uniformed policemen knock the one-armed bandits to the floor in the raid on the Lookout House. These machines were operated by eager gamblers just hours before. (Photograph by the Kentucky State Police; courtesy of the Dave Horn Collection.)