CHAPTER 4

Mad Dogs and First Fridays

By 1969, Ann and David felt they could no longer stand living in Dallas. They looked at San Antonio and Corpus Christi as towns with more tolerable political and lifestyle climates and some possibilities for a new law practice, but from the beginning, Austin was the destination they longed for. Two years earlier, Sam Whitten had gotten a job teaching in the library school at the University of Texas, and the Whittens bought a two-story rock house near the campus that would soon become famous for its parties of hard-drinking liberals. During the time that the Whittens were away, David and Ann loaded up their children on weekends about once a month and drove down to visit their closest friends. The Richardses’ chance to act on their wishes emerged at a political party in Austin one night—Sam Houston Clinton asked David (who by now was being called Dave by most of his friends and colleagues) whether he would care to join him in his practice. Though David had known the older man in Waco, their friendship had put down deep roots at gatherings of the Young Democrats and labor unions and during many nights at the Scholz Garten.

The Richardses were given pause by their forays to Washington, which had not gone well. They thought their children were old enough to have a voice in such an important matter. The parents called the family together one evening, took votes by shows of hands, and frankly told the kids that they had a plan to move to Austin, but that they really didn’t know how it would work out. Cecile was eleven, Dan was nine, Clark was six, and Ellen was four. On hearing the prospect of moving to Austin, the kids raised a clamor as if they were about to go off on one of their camping expeditions. Dan had one caveat and specific request—could they please find a house on a street where, if he had a dog, it would not always get run over?

The law office of Sam and David at first consisted of cubicles at the headquarters of the AFL-CIO. Ann meanwhile took over the housing search. Eddie Wilson, who had come into their lives in Dallas, was married to a woman named Genie, and after a year of teaching school in South Texas, they had returned to Austin, where Eddie grew up, and he renewed the friendship with Ann and David. Eddie had gotten a job as a lobbyist trainee for a beer distributor. “I happened to be riding around with Ann that day she saw that house up in the hills,” Eddie said. “She made one walk-through and said, ‘This is it,’ and it was the one they bought.”

West Lake Hills was then a scenic, sparsely populated enclave strung along the cliffs of the Balcones Fault and the winding course of the dammed-up Colorado River. It had been developed by a longtime criminal defense lawyer, Emmett Shelton, who acquired much land in the county by taking quitclaim deeds from cedar choppers who couldn’t afford to pay their attorney bills when they got in trouble. The house that Ann discovered off Red Bud Trail was fairly large, sat on two acres, and had a grand view of the woods and river and the Austin skyline. “The house faced out over a canyon called Oracle Gorge,” Ann recalled, “so named because if you stared down into it long enough, the answers would come.” The family spent the first night on the floor in sleeping bags. As darkness gathered, the city spread out before them, glimmering, its skyline dominated by the Texas Capitol and the spire of the university tower.

“Mama,” Clark said, “it’s like a garden of lights.”

After deciding to do some renovating, Ann had an architect draw up some preliminary plans, but then she found a carpenter named John Huber, who had known them in the political battles. He was also known for getting sauced and writing doggerel verse that the Austin American-Statesman sometimes printed on the editorial page. “I sat down with John, who had built a number of houses in his life, and showed him on a piece of paper what I wanted to do,” Ann wrote. “He said, ‘Oh, don’t worry about it—we don’t need an architect. We’ll just build it.’ I liked to hear that. It wasn’t as brave as Mama going to town and getting day help, but it was close. John would arrive in the morning and say, ‘Well, what do you think we ought to do today?’ And I’d say, ‘Well, I don’t know, why don’t we knock out the living room wall and start there.’”

Over the course of several months, Ann and her new chum worked on a large living and dining room built over the master bedroom suite. She clearly did not envision a cozy place where the family would watch television. The upper room had a vaulted ceiling, tiled floors, and artful windows framed in stained wood. Ann had a fine eye for rugs and original art and other interior décor. A screened-in porch warded off mosquitoes in the warm season, and there was a large patio and a swimming pool. “John was the most hilarious man,” Cecile told me. “He and Mom were really working closely together. After the house was finished, he came back and built us a chicken coop, and so we had chickens, and then for Mom and Virginia the big deal got to be organic gardening, so he built her a greenhouse and the bin for composting.”

Her younger brother Dan reminisced, “I thought we’d moved to the country. Back then there wasn’t a lot out there in West Lake Hills. It was a great place for kids, though. We could camp out, hang out in the woods all the time, and there was not the concern about getting run over like there had been in Dallas. We’d build tree houses and do whatever we wanted to do. Emmett Shelton, the town marshal, lived right up the hill from us. His father, Emmett Sr., was the one who developed West Lake Hills. Emmett’s son Ricky was my age. We became friends, and all the Shelton kids were troublemakers . . . So that was highly entertaining.”

“What kind of trouble?” I asked.

“Oh, just out in the woods, setting things on fire, throwing rocks at cars, that kind of stuff. And the older Shelton boys had dune buggies; they all drove dune buggies. Constantly there was a mechanical repair operation going on in their driveway.”

Ann volunteered at the small Eanes Elementary School, where she and Virginia Whitten, now its librarian, dreamed up and constructed elaborate bulletin boards for the kids of West Lake Hills to ponder. Through a small Episcopal church in the scattered suburb, Ann and David became friends with people associated with the university—among them Standish and Sarah Meacham. Standish was a scholar of American history and later a dean at the university, and Sarah joined the library faculty of West Lake’s grade school; he was also an accomplished parlor piano player. David and Ann likewise grew close to Mike and Sue Sharlot. He was a professor at the law school, at one point its dean, and Sue was an administrative nurse. She later got her own law degree.

Virginia Whitten was the friend that Ann called “the rock.” Reticent, practical, sometimes uproariously funny, she was the best friend Ann ever had. In their rock house on West 32nd Street, the Whittens started a tradition of several years’ standing called First Friday. One night every month, they opened their home to all who would bring booze and something to eat, and the parties went on for hours, a packed house of shouting, laughing, arguing people—it was home base for Austin liberals. At First Friday, you could find yourself talking to Russell Lee, the photographer who contributed sensational Farm Security Administration images while working with his peers Walker Evans and Dorothea Lange; or John Henry Faulk, the radio comedian who had been blacklisted during the McCarthy mania, but then had won a libel suit and become a resident sage in Austin and an authority on the Bill of Rights; and uproarious Molly Ivins and quiet Kaye Northcott, whom Ronnie Dugger hired as the new editors of the Texas Observer. After several months of First Fridays, Virginia threw up her hands and declared that everyone had to be out of her house by ten thirty. It seldom happened, of course. “The best stories,” Lynn Whitten told me, “came the next morning, when we were cleaning up and everybody was reporting on who said what.”

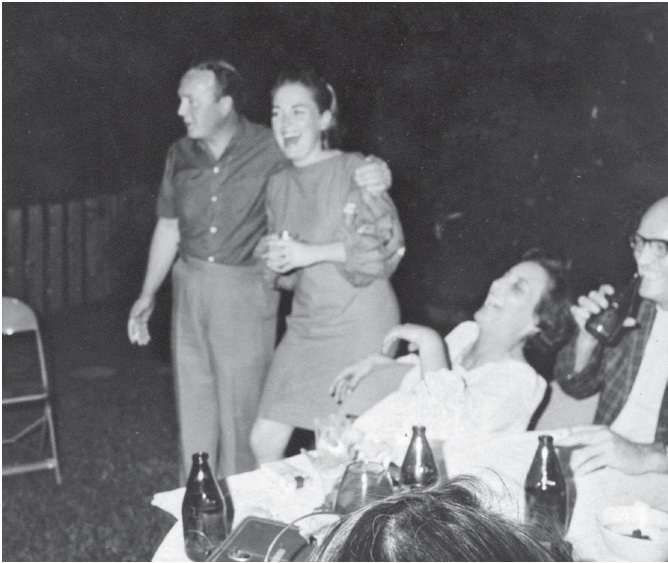

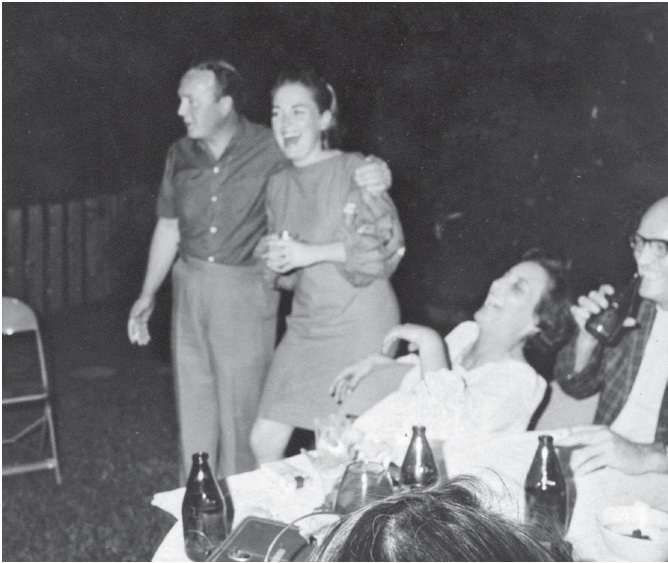

At a monthly First Friday party that spilled into the backyard of Sam and Virginia Whitten, Ann laughs at a joke told by John Henry Faulk, the radio humorist blacklisted during the McCarthy red-baiting episode, who won a landmark libel case and returned to his native Austin as an authority on civil liberties and the United States Constitution. The man at far right with glasses is Sam Whitten.

Ann wrote about the friendship that she and David shared with the Whittens: “Every weekend we would get together at someone’s house, and after dinner David and Sam would argue. They would argue about anything you could name. They would argue with each other, and then if other people were around they would team up and argue with whoever was there.”

Lynn Whitten said, “Most nights there wasn’t a whole lot of shouting in our house. But David and Daddy would go on and on, and it got louder and louder. One time I ran downstairs and shouted at David, ‘You quit yelling at my daddy!’ Daddy let out a big laugh, caught me up in a hug, and assured me everything was all right. It was so ridiculous, because they agreed about everything.”

When eddie wilson wasn’t lobbying for the beer association, he managed a psychedelic rock group called Shiva’s Headband, which was one of the most popular groups in Austin as well as a house band of the Vulcan Gas Company, a club on Congress Avenue with fanciful poster art and strobe lights but no alcohol for sale. Steve Miller, Boz Scaggs, and Johnny and Edgar Winter were among the burgeoning talents who passed through the Vulcan scene. No less hopeful was Spencer Perskin, another alum of Stan Alexander’s folk-music club at North Texas State, and now the leader of Shiva’s Headband. He was a talented singer and player of lead guitar, the electric fiddle, the harmonica, and an electric jug. They landed a recording contract with a major label, and Eddie tried to enlist David in the management of the band. David couldn’t understand what they wanted him to do.

Eddie also called on him to intercede in behalf of some avant-garde radio types. A local businessman had decided to redesign the format of his station to appeal to the youth culture, and the station had hired a group from San Francisco to remake the image. The second day on the air, the new regime aired a lengthy tape produced by the Pacifica station in San Francisco. It included an interview with a mysterious writer named M. D. Shafter. The owner happened to catch that part of the program and blew a gasket. He called the station, ordered “that filth” off the air, and promptly fired all the new arrivals. M. D. Shafter, it turned out, was the alias of one Gary Cartwright. David had to tell Eddie they really had no case.

Shiva’s Headband could never fulfill its promise because Perskin kept getting busted on marijuana charges. (Later in life, Ann would regularly be called on to try to help him find an easier place to do his time.) By 1970, the Vulcan Gas Company was about to close. One night, Wilson said, he and some pals were riding around South Austin and drinking beer when they pulled off in an alley to relieve their bladders. He saw a dark hulk of a building, and he soon took Ann and David on a tour of his prized discovery. “It was just enormous—a great cavernous space,” Ann recalled. “Most of the windows were up high and were broken out, and it was all cobwebby and had many years of filth and about a city block of junk stored in it. Eddie said, ‘Look at this wonderful place. This is going to be the biggest and best music spot in Texas.’ Well, Eddie was always given to exaggeration, and David and I looked at each other and thought, ‘Lord help us, what is he off on now?’”

But their children got the idea at once. “For us,” said Cecile, “this was really cool, this place where Armadillo World Headquarters came to be. I was in the sixth grade when we moved to Austin. Dad was defending the rights of these self-proclaimed anarchists to hand out an underground paper called The Rag on the University of Texas campus, and they were participating in all these protest marches. I remember Mom taking me to see Jane Fonda. And the counterculture overlaid everything in Austin. It was such a young person’s place. Growing up in that period permeated our lives, and I think it was that way for Mom, too. In Dallas, I remember them having one record album—This Is Sinatra. Once we got to Austin, suddenly we were going out to see Willie Nelson and Jerry Jeff Walker, and now at home we were listening to the Jefferson Airplane.”

In 1967, Bud Shrake had finished his novel Blessed McGill, an inspired western novel, and Jap Cartwright had gotten fired by the Philadelphia Examiner after a three-month stay. Cartwright rallied to write an acclaimed essay for Willie Morris and Harper’s called “Confessions of a Washed-Up Sportswriter,” which brought him many prestigious freelance assignments—work that later made him a founding contributor of the Austin-based magazine Texas Monthly.

Bud’s reporting for Sports Illustrated took him to Thailand, Malaysia, Cambodia, Hong Kong, Japan, Algeria, and Lebanon; sent to Argentina to write about the boxing champion Carlos Monzon, he wound up jailed and incommunicado for several days as a suspected terrorist. The authorities had a habit of throwing people like that out of planes high over the Atlantic Ocean. Bud’s first wife, Joyce, was an actress turned English professor. She was the mother of his two sons; they married and divorced each other twice. For a few years, he had a romance with Diane Dodd, a gorgeous girl he had met when she was a University of Texas student. She was the model for the character Dorothy in his novel staged around the Kennedy assassination, Strange Peaches. When they broke up, she boarded the now-legendary bus of Ken Kesey and the Merry Pranksters, and later died in her midtwenties from a brain tumor. After numerous adventures abroad, Bud convinced his New York editors that he could deliver on his assignments just as well while living in Austin. He arrived with his stunning new wife, Doatsy Sedlmayer, the daughter of a Long Island banker and an assistant editor at Sports Illustrated.

About the same time, Jap moved to Austin with his wife, Jo, and their children. He published a novel about pro football, The Hundred Yard War (1968), and then got busted for handing two joints to a couple of hippie strangers who knocked on his door and maneuvered inside their apartment by talking about friends they had in common; they were undercover narcotics agents. Jap and Jo were evicted, their Volkswagen van was repossessed, and he faced trial at a time when Texas judges and juries were still handing down decades-long prison sentences for marijuana possession. David Richards was a backup on the defense team when the case finally went to trial in February 1970. The lead attorney was Warren Burnett, of Odessa, the most masterly Texas trial lawyer of his generation. Burnett shredded the prosecution’s probable cause for a search warrant of Jap’s house, which prompted the irked judge to declare a mistrial. The district attorney dropped the charges, but that event did not get nearly as much press as the arrest had, and the episode did not help Jap’s marriage. Toward the end of his life, Bud told Brant Bingamon in an interview, “My name was on the warrants they served the day in 1968 when they busted Cartwright, but an officer who knew me slightly and had read Blessed McGill scratched my name off the list.”

On May 4, 1970, Ohio National Guardsmen fired into a crowd of antiwar protestors on the campus of Kent State University in Kent, Ohio, killing four students. The next day in Austin, a demonstration in protest of the Kent State violence spilled from the University of Texas campus into surrounding streets. The police responded with tear gas and force—a dozen injuries were reported. Leaders and allies of the students obtained a parade permit from the city, and on May 8, 25,000 people marched peacefully through downtown Austin. To the astonishment of many, the cadres of police lining the route kept their distance. That summer, the Armadillo World Headquarters opened, just as Eddie Wilson had said it would. Bud invested a thousand dollars in the venture, and David drew up incorporation papers for the club. Eddie and his principal partner, the entertainment lawyer Mike Tolleson, built on concerts by Willie Nelson, country-rock singer-songwriters like Michael Murphey and Steven Fromholz, and Nashville rebels Waylon Jennings, Billy Joe Shaver, and Guy Clark. The Armadillo soon hosted shows by the Pointer Sisters, the strange little Irish dynamo Van Morrison, and Bruce Springsteen when he was first becoming a star. Wilson recalled, “Ann liked being backstage, mingling with the bands and peeking at the crowds. The pleasures taken in the Armadillo were awful brazen. She’d ask me, ‘How in the world do you keep from getting busted?’ I’d laugh and say, ‘I don’t know, Ann. I don’t know.’”

Those friendships and evenings led David and Ann to become charter members of an unruly crowd called Mad Dog, Inc. David drew up its articles of incorporation, too. Bud’s generosity as an investor in the Armadillo won them an office in the big hall, which was adorned with surreal armadillo murals by the talented resident artist Jim Franklin, who lived upstairs with his pet boa constrictor. A widely distributed photo of the Mad Dog founders shows them standing and sitting around a large table. Toward the end of their time in Dallas, Ann had worn her dark hair long and straight, tied with a scarf in back. Now it was dyed blond in a heavily sprayed flip, like that of the actress Mary Tyler Moore. David was grinning and wearing the only coat and tie in the room (because, he said, “I was the only one with a goddamned job!”) Smoking a cheroot, Bud was seated beside David, and next to Bud was a young woman naked from the waist up, except for a sign positioned above her lovely breasts that read “Jap.” Though everyone remembered Julia, a promising academic and the companion for a time of the architect and raconteur Stanley Walker, no one could really say what her stunt was all about. The same could be said of Mad Dog, Inc.

The Mad Dogs’ motto was “Doing Indefinable Services to Mankind,” their credo “Everything that is not a mystery is guesswork.” Their grandest hope was to buy their own town and write their own laws. In his book Texas Literary Outlaws, Steven Davis described their stab at buying Theon, a burg northeast of Austin. They were at a place called the Squirrel Inn discussing the plan when Bud wanted some water to dilute his Scotch, opened the joint’s refrigerator, helped himself to a pitcher, and poured some of it into his glass. He downed it in one gulp.

The “ice water,” as it turned out, was kerosene. With Shrake ailing, the group rushed back to Austin but was stopped by the highway patrol. Cartwright got into an argument with the cop, and the Mad Dogs wound up spending the night in the Williamson County jail. A doctor friend was called to come check on Shrake. After a cursory exam, he gave Shrake a handful of pills and told him to swallow them all. Those turned out to be speed. “He thought that would make me feel a lot better,” Shrake recalled. “And I guess it must have. My heart exploded about twenty-five times and I bounced around the walls of the cell for a while.”

The involvement in the movie business of Bud and Jap brought into the Mad Dogs’ company prominent actors, including Dennis Hopper and Peter Boyle. Those associations resulted in one wild film shoot in Durango, Mexico, and the resulting cult western starring Hopper and Boyle and written by Bud was called Kid Blue. Bud reminisced that on the Kid Blue shoot he discovered cocaine, developing a habit that lasted twelve or thirteen years. He also got a bit part as the town drunk. The veteran actor Ben Johnson, who played the sheriff, erupted one day and whacked him on the head with his gun because he was tired of looking at him. Bud was so tall that it seemed as if he fell for about two minutes. Flying Punzars were adept at that.

Mad Dog, Inc.: The board of directors of this group probably met just on this one occasion, according to David Richards, who filed the incorporation papers. David is the man wearing a coat and tie at the table, upper right. Across the table from him is Ann, whose hairstyle then resembled the flip of actress Mary Tyler Moore. Bud Shrake is seated on David’s right. On Bud’s right, topless but for the sign “JAP,” is a young woman filling in for the absent Gary Cartwright. Austin, 1970.

Bud later commented on his addiction in e-mails to Brant Bingamon:

With the money I spent on coke, I could have bought a suburb. I made some very poor decisions because of it, but it did lead me into some interesting places. You suddenly look around, and it’s five o’clock in the morning and you realize you are in some stranger’s house with a bunch of people you don’t know and everybody is very loaded and it might be a surfer’s house or an actor’s house in the Hollywood hills or it might be a roomful of Mexican gangsters. . . . I have one piece of advice about cocaine—do not use it. It will make you stupid.

Bud and Jap also wrote a script about a bull rider, called J. W. Coop, which the actor Cliff Robertson wished to star in. He had come to Texas and hung out with the writers for a while. Don Meredith, the Dallas Cowboys’ quarterback, watched the man closely one night and murmured to his writer friends and David Richards, “That’s not Cliff Robertson. I’ve met Cliff Robertson.” Another night Jap goaded the vain actor by introducing him as Biff Richardson.

Later the actor sent them a letter of regret that he had been unable to get the movie produced. They shrugged and moved on. Then, amazingly, the film premiered, with a virtually unchanged script and all credits claimed by Robertson, who was coming off an Oscar-winning performance in Charly. A lawsuit over the writing credits ensued in an Austin state district court, with David representing Bud and Jap. The matter might not have gotten so rancorous had Robertson not claimed that he had gotten caught up in a Manson-type gang, he allegedly characterized Jap as an ex-convict hustler. Bud sent the actor’s lawyer a letter on Mad Dog, Inc., stationery that vilified Robertson, and he attached a clipping from the Fort Worth Press: “Police Believe Frozen Dog Weapon in Beating Death.” He signed off, “Mad Dog on Prowl.”

At trial, David said his plaintiffs “looked like street people, with coats and ties that didn’t fit and a distinct aura of seediness.” The handsome and suave Robertson schmoozed with the gallery, prospective jurors, and the judge. After that first day, David told his clients that they had to be back in court at eight o’clock the next morning. On hearing that, they quickly caved in and agreed to a settlement giving them screenwriting credits and at least some of the money they had coming. But on the screen in the revised print the Texans’ names floated in yellow against a field of wildflowers the same color.

Mad Dog, Inc., was mostly beer, whiskey, and marijuana talk, and the collective brainstorm quickly petered out. But before it did, the wild seeds proposed a magazine called Mad Dog Ink, which, in its first issue, would feature the prison poetry of Candy Barr, a famous stripper and porn movie star who had run afoul of Texas’s antimarijuana laws. Another brainstorm was a publishing company named the Mad Doggerel Vanity Press. Jap, Bud, and others egged on an heiress to write a novel titled Sweet Pussy, which they proposed to publish. All this was extravagantly sexist, of course. Bud and Jap claimed that they could read fortunes by inspecting bare nipples, not mere lines in hands, and some young women peeled off their shirts to let them. Ann saw no humor in that, and she occasionally let them know it. But she did consent to be seated and photographed at a table with a young woman who was topless except for a sign across her chest.

She and David enjoyed going out on the town in costumes. She liked to make herself up like Dolly Parton, her face smeared with lipstick and padded boobs projecting from her shirt like a pair of howitzer shells. One night they went to a beer joint and honky-tonk called the Broken Spoke. “This one guy asked me to dance,” Ann recalled his approach to the two-step. “If he had let me go, I would have flown through the walls. He was driving me around that dance hall like a truck, and he said, ‘I don’t care if you’re Dolly or not. Come back to the Motel 6 with me and we’ll have cotton all over that room.’”

Ann was a practiced flirt, but a part of her was quite conventional about sex and fidelity. She and David had a good friend named Bill Kugle. He had won election to the legislature from Galveston, where he played a role in the dismantling of the long-established but illegal gambling empire of the Maceo family, and the backlash in Galveston was so harsh that he abandoned his House seat and moved away to the East Texas town of Athens, where he set up a practice with the esteemed William Wayne Justice for a while. Kugle was thoroughly delightful but randy as a goat. “Ann was really shocked one time when Bill made a pass at her,” David said. “She couldn’t believe he was so direct and explicit.” But another night at First Friday, an academic who considered himself a Don Juan hit on Ann in a particularly obnoxious manner. The man’s daughter, who witnessed the incident, later told me, “I’ve never seen a woman take down a man like that. She sent him out of there like a dog with his tail between his legs.”

David and Ann were considered the straightest Mad Dogs, but they held their own in the frolics. Their home, said Jap, “became a sort of Mad Dog sanctuary.” The New York Times editor Abe Rosenthal appeared one night and was greeted at the door by Ann, who was costumed as a giant tampon. It had a smear of painted blood and a string coming out from the top. (You had to have been there, I suppose.) Rosenthal was charmed enough that he devoted half a column to the party and its hostess. “Bud was there, then Jap showed up,” David recalled, “and they went into this routine that was hilarious and absolutely unscripted. We had a big Afro-style wig sitting around from some other costume event. Bud snatched it, put it on, and went into this act in which he was Dr. J.”—the pro-basketball star Julius Erving. Rosenthal got into the spirit of the romp and started conducting a mock interview of the tall writer turned basketball star. “How can you achieve the kind of stardom that has come to you?”

“Learn to dribble, white boy,” Bud replied.

Years later Rosenthal wrote again, “One of the best parties I ever went to was in Austin, Texas. . . . I realized later why I had such a good time. None of it was catered, a form of surrogacy that dominates evenings in most big cities. . . . The crayfish were cooked in Ann’s kitchen and she spread them out on the table herself. There was music—not a hired pianist but some guest picking on a guitar. . . . There was a great stand-up comic—a novelist with a buzz on [Shrake]—right there in the living room, not on television. And the guests were not catered either—Ann invited them herself for her own party.”

In his memoir David wrote about another night of festivity at the house in West Lake Hills. It was a fund-raiser for Vietnam Veterans against the War.

The music was provided by a group that called themselves the Viet Gong or some such moniker. . . . At some point in the evening, the town marshal, who was our neighbor, arrived in response to a number of totally justified noise complaints. I remember thinking that I had placated him by toning the music down and promising to shortly end the band’s efforts. The marshal’s report to the town council was more alarming. He claimed he had been surrounded by a bunch of stoned hippies who kept screaming, “Off the pig.” Who knows, it was a large yard, and I suppose something like that could have happened.

One afternoon in August 1973, Ann again displayed her gift of being in places where memorable events occurred—in this case, the daylong party following the recording of Jerry Jeff Walker’s ¡Viva Terlingua! album in Luckenbach, Texas. A photograph of Ann appears in the album’s liner notes. Thoroughly wasted, she looks primed to topple right off the picnic table. Eddie Wilson was fond of saying that life in Austin in those days was fueled by cold beer and cheap pot. Riding in a convertible one day with David and—who else?—Jap Cartwright, Ann had taken a few puffs off a joint and soon realized that she quite enjoyed marijuana. “But Ann was an alcoholic,” insisted Jap Cartwright. “She had a vodka problem, she didn’t have a drug problem.”

More perilous to her health than the marijuana was her prescription medicine Dilantin. Since 1938, the Pfizer drug had been the standard preventive for epileptic seizures, but the National Center for Biotechnological Information eventually issued a stark warning: “Tell your doctor if you drink or have ever drunk large amounts of alcohol. . . . You, your family, or your care-giver should call your doctor right away if you experience any of the following symptoms: panic attacks; agitation or recklessness; new or worsening irritability, anxiety, or depression; acting on dangerous impulses; difficulty falling or staying asleep; aggressive, angry, or violent behavior; mania (frenzied, abnormally excited mood.)”

“When I was a kid,” Clark Richards told me, “I remember Mom would be cooking dinner, and she would ask me to make her a martini. Mom’s version of a martini filled up about the size of the glass you’re holding there.” He indicated a ten-ounce glass of water I had in my hand. “I filled it with ice,” Clark went on, “and then to the brim with vodka, with a drop of vermouth and a twist of lemon. She would drink one without a problem, maybe a couple of them. I mean, I’m ten years old—what did I know about booze? That’s just what Mom drank.”

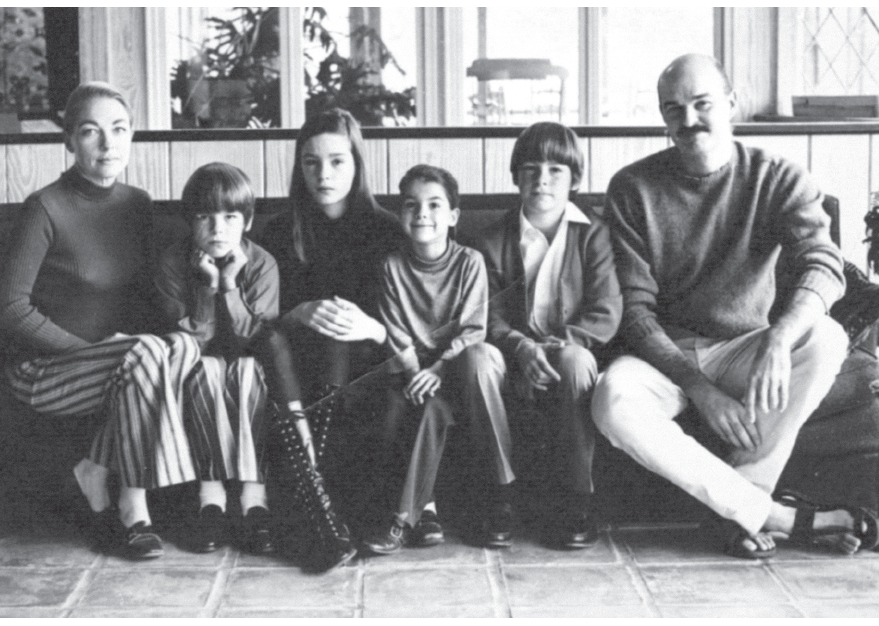

After the move from Dallas to Austin. From left, Ann, Clark, Cecile, Ellen, Dan, and David Richards. Early 1970s.