CHAPTER 19

The Rodeo

For the rest of their lives, Ann and Bud explained their relationship with the high school expression “going steady.” In April 1990, when she was struggling to put away Mattox in the runoff, Bud wrote, “My prayers are with you (and also my cosmic powers which are better left undefined, sort of like Mad Dog). I can’t even imagine how tired you must be, and how in need of . . . I started to say solace, but that’s not the word. Maybe a good hug is all I mean.”

“So far, so bueno” was Bud’s droll, semioptimistic maxim of life. But even he acknowledged how bleak the situation appeared that summer. Amid reflections on the press’s tepid response to her environmental policy plan—the one I wrote—and Saddam Hussein’s provocative comparison of Britain’s creation of Kuwait to a nipple carved from the breast of Mother Iraq, Bud offered an anecdotal detour and parable.

Dear Ann,

. . . I was kind of tired and my ankle hurt this morning, so I gave myself a day off. The dogs jumped in the car and I went to a long breakfast at Maudie’s Cafe, where I read the Dallas Morning News and listened to Ab, Maudie’s husband, the cook on Saturday mornings, as he would occasionally come out of the kitchen and make pronouncements. Once after he had been making a racket he came out and said, “No problem, folks. I’m just communicating with my ancestors.”

Later Ab sat down and said, “It’s a beautiful day in Chicago.”

I looked up from the paper to listen.

“Back on the farm at four in the morning, doing the chores and freezing to death, milking the cows and slopping the hogs, I would be listening to this old radio in the barn, and every morning a man came on the air and said, ‘It’s a beautiful day in Chicago.’ That’s always stuck in my mind. No matter how bad it looks to me, it’s always a beautiful day in Chicago.”

Ann had been in the race for a year now, and like a long-distance runner, somehow she had to find the kick, the sprint to the finish. Bud’s days of trying to overcome his crises had not all been beautiful, either, and she helped guide him toward AA. In those days, movies and AA meetings were how they often dated. In late June, she wrote him:

I’d love to go AA-ing with you but I am off to Washington, New York, and Miami this week. Home on Friday. I had such a good time listening to the saga of your father at the nursing home that I can’t wait to hear chapters 2-3-4. . . . I’ll call when I can play. Hope you’ll go to AA without me—great people.

Love, Ann

Late that summer, Bud accompanied Ann to a benefit that Willie Nelson put on for her at the Austin Opry House. There was a good deal of laughter and much good music that night, but we had the air of people bunched up under siege. Glenn Smith told me that after the primary and runoff: “The first poll we got back showed her seventeen points down to Clayton. But that’s a strange thing: Ann was way scared of losing the primary to Mattox—she just didn’t know how she could face all of those people who believed in her—but she wasn’t so afraid of losing to Williams. Those seventeen points didn’t daunt her. She didn’t think she had much of a chance of overcoming that, but she was much more relaxed. From the beginning, she just had a more happily aggressive attitude about it. That was a role Ann was very comfortable in—the liberal fighting an uphill fight against powerful good old boys. Her attitude was so much better in the general election. Even in those early days.”

Glenn and the rest of the original team had reason to be proud. The primary had been a brutal contest in which they were backed to the edge of an abyss, yet they fought back and won. Still, Ann wanted Mary Beth Rogers to take over as campaign manager, with major help to come from Jane Hickie and Jack Martin. Mary Beth did not share Glenn’s belief in the upbeat morale of the campaign team. And in her recollection, on the night of Willie’s benefit at the Opry House, Ann was twenty-seven points down.

Several women who worked for Ann have said the campaign shake-up was necessitated by need to get rid of “the guys.” But the dysfunction was not that simple, Mary Beth told me. “In the first part of the primary, the campaign was pretty much run by Glenn and Mark and Monte Williams and Lena Guerrero. And people wound up at each other’s throats. Boy, that was a low point, even though Ann managed to squeak it out.” Some of Ann’s team thought that Bob Squier’s ads had not measured up to his national reputation. Mark McKinnon was then in a short-lived partnership with the Austin politico Dean Rindy. The Richards team decided to give Rindy and McKinnon a chance to brainstorm and produce the ads for the general election. Before anything got on the air, half of that partnership departed when Rindy intimated to Ann that she dressed like hell; there were no more sightings of Rindy on the campaign team after that.

But Mark had been close to Ann for a few years; he had been one of the trusted readers of the manuscript of her book. “Harrison Hickman had conducted a poll about the general election,” Mary Beth said. “It was about two weeks after Ann had won the primary. Mark in his innocent bouncy way just kind of blurted out how far behind she was in the polls, and how awful it was. Ann gave him this look—I thought she was going to start crying, I think she held it back. She got so mad at Mark, after that meeting she didn’t want to have anything more to do with him. That’s when she got Jane and Jack and me to come in and take over.”

Ann, conservationist and movie star Robert Redford, and Jim Hightower at a joint campaign event in 1990. Ann edged Clayton Williams in the race for governor, but Hightower’s popularity with the media and figures in the entertainment industries was not enough to get him past State Representative Rick Perry in the race for agriculture commissioner.

George Shipley recalled a campaign ad that Cathy Bonner produced during that period of flux. “It had rodeo footage, and the theme of it was that Ann was going to put Texas back on top. They ran it for two or three days. But the sexual innuendo that Ann was going to be ‘on top’ was offensive to a large number of white men.” Squier came back aboard to do the advertising, while Glenn and Monte started a consulting team and continued to play a role in the campaign. “I was a lot happier,” Glenn said. “I was exhausted, and there was nothing I could do to recast the way Ann thought of me. She didn’t really think badly of me, to my knowledge. It was more like, ‘Where are all the people who said they were going to be with us? I thought this guy was going to be a figurehead, and here he’s been making real decisions.’ I didn’t feel any resentment when Mary Beth came in. She took a lot of pressure off me. Also, I wanted Ann to win.”

Glenn smiled, remembering a debate prep that turned out to be one of his favorite moments in the campaign: “Somebody had given us use of one of the big houses above Town Lake. I was sitting on a sofa with Ann, and she said, ‘You know, Glenn, I don’t know how to deal with you because you’re not obsessive-compulsive enough.’ I had a pen in my hand, and I leaped up and threw it against the wall and said, ‘Fuck you, bitch!’ Then I sat back down and said, ‘How was that?’ She doubled over laughing, but nobody else knew what was going on.”

Mary Beth recalled that evening quite another way. “The situation was real delicate,” Mary Beth said of handoff from the primary team. “To his credit, Glenn made it easy, and we’ve been friends to this day. But we also had to get Lena out of there. There was going to be a coordinated campaign for all the candidates under the direction of the party. I was being given the role of having to do all the dirty work for Ann, and I had to convince Lena she would be more effective, and play a greater leadership role, if she headed up the coordinated campaign. And then we had to convince everybody else on the coordinated campaign that Lena could do it, and that took a month. During the primary there had been a debate preparation in which a developer had loaned us his big house. I’d never seen anything like it—such out-and-out animosity on Lena’s part. It was one of those things where you’re thinking, ‘I don’t want to be in this room.’”

My wife, Dorothy, had vivid memories of that evening as well. Bob Squier had flown down from Washington for the debate prep. Perched on a steep hillside, the borrowed mansion had a deck where people could enjoy the view—also a sturdy railing to keep them from toppling off if they had had too many. Dorothy looked up at one point and saw Squier out there in his solitude, walking the railing like a gymnast on a high wire. The Richards campaign had been a circus up to that point, and the big-name pro from Washington was an oddly perfect fit.

“Clayton had beaten a big field of opponents,” Mary Beth said. “He was just so arrogant, so contemptuous of Ann. He was on track, and he would have beaten her. The demographics in the state, the number of self-identified Republicans, were changing fast. And Clayton was doing very well until we began to pressure him.” One of those times, they believed, came in July. The press had carried stories of Williams saying that Ann was sympathetic to traitors, followed by a former prisoner of war questioning her patriotism on Williams’s behalf. Then came a barrage of attack ads in that vein on radio. At a joint appearance in Plainview, Ann walked up to him and said, “You’ve got to get this stuff off the air.” His adversaries in the primary had not confronted him that way, and it seemed to rattle him.

Two events in the Gulf of Mexico worked to Ann’s advantage that summer. First the Mega Borg tanker exploded, releasing around 4.6 million gallons of oil, then a tanker-barge collision sent 500,000 more gallons into the wetlands of Galveston’s Seawolf Park. The state had no workable plan in place to deal with calamities of that scale. Ann raced down to Galveston to view the muck and said, “I am horrified that Bill Clements has failed to act to protect our fragile environment. Clayton Williams brags that he is cut from the same cloth as Bill Clements. Right now that cloth is soaked in oil and is wearing mighty thin.”

Mary Beth said, “We came up with this seven-point strategy for the campaign. We had to tell Clayton’s story. We had to tell Ann’s story. We had to galvanize women voters. Especially suburban women. We had to raise six million dollars. We had to turn out our Democratic base in East Texas, the inner cities, and along the border. And we had to have some good luck.

“We started doing crash research about Clayton Williams’s businesses. Paul Williams was discovering things that had never been out in the open before. And people couldn’t believe it. At the start of our focus groups, voters would start out being for Clayton Williams. But when we laid out facts about his career, they’d switch. So we knew that if we could get the money to put that on television, we’d have a shot. We started targeting big donors. Fred Ellis and I went down to see Walter Umphrey [a personal injury lawyer in Beaumont]. I told him, ‘Look, we have poll results and we have focus group results. If we can put this argument on television, we can knock this guy down. But we’ve got to get on TV.’”

There were about six Democrats with that kind of wealth that they called on. A pariah to Republicans, who loathed all “trial lawyers,” unless of course they gave money to Republicans, Beaumont’s Walter Umphrey contributed a little more than $100,000 and lent her campaign $200,000.

The first draft of “Meet the Real Clayton Williams” read: “Over the next several weeks, the Ann Richards campaign will begin a series of public service press releases to introduce the public to Clayton Williams.

“These releases will introduce the real Clayton Williams, the man behind the $6 million television campaign, the junk bond wheeler-dealer whose big grin shows that he thinks he can do what has never been done before: the leveraged buyout of the State of Texas.”

It was a joke that the attacks were “public service announcements,” and many of the accusations were too wonky to catch on with voters. But some of them stuck. Private property rights are sacrosanct in rural Texas; the Richards campaign found a 1981 Houston Chronicle article in which Williams spoke in heavy-handed fashion about using eminent domain—or condemnation law—to force his oil and gas pipelines across anyone’s land: “They can protest as to what we pay them, but we have a right to lay our pipelines across anybody’s property at any time.”

Paul Williams found that in 1984, the Texas Railroad Commission reported that one of Clayton Williams’s oil companies and a contractor called Bulldog Construction Company had been cited for intentionally dumping 25,000 barrels of waste mud and oil into a tributary creek of a lake that provided drinking water for the small town of Brenham. Partners and competitors in the oil and gas industry had sued his companies more than 300 times. Two large federal suits, which alleged fraud, deception, restraint of trade, and illegal fixing of natural gas prices in order to cheat royalty owners, had been settled by Williams’s lawyers. The most recent lawsuit involved his long-distance telephone company, ClayDesta. One of his first employees claimed Williams lifted his business plan, promised him 30 percent equity in the company, and then fired him two years later. Williams bristled in the deposition, “I fired him and gave him fifty thousand dollars because he wasn’t doing his job. That’s more than the man deserved.”

Ann released all her income tax returns and challenged Williams to do the same. He bragged that it would take an eighteen-wheeler to haul all his personal and business tax returns. A young member of Richards’s campaign team, John Hatch, had friends in the trucking business, and they arranged to haul an eighteen-wheeler to Williams’s campaign headquarters. A Williams spokesman responded haughtily, “Ann Richards is a liberal elitist who is comfortable hobnobbing in the boutiques of San Francisco and Greenwich Village with the likes of Jane Fonda and Michael Dukakis.” But the counter did not line up with the gibe—boutique liberals were not often acquainted with people who knew how to park an eighteen-wheeler.

None of the charges could have overcome Williams’s lead in the polls and huge advantage in funding. But the accusations about his business practices angered him. In September, he bragged that he was going to “head and hoof her and drag her through the dirt.” That is a reference to roping cattle, which did not play well among women who were already put off by his roundup rape joke.

Inexperienced aides in the campaign office responded with a colorful non sequitur. Mark Strama, whom Ann would later help win a seat in the legislature, was then a twenty-two-year-old, fresh out of college in Rhode Island; his job at the campaign was to run errands. Strama and some pals came up with a top ten list of silly characterizations of the Republican and posted it around the office. Chuck McDonald had joined the team as a press aide; he later became a sought-after public relations consultant, but he got the campaign job in part because his mother was a prominent Democratic legislator from El Paso. When Williams made the crack about Ann falling off the wagon, reporters started calling for a response. McDonald was caught off guard, and both Bill Cryer and Margaret Justus, the seasoned campaign press aides, were out of the office. His gaze fell on the top ten insults the young staffers had compiled. Reading the first one, he told a reporter from Amarillo, “Clayton Williams is a fraudulent honking goose.” The odd rejoinder sped around newsrooms all over the state. “Ann and Bill Cryer were driving in Nacogdoches and heard this on the radio,” recalled Mark Strama. “Bill said he literally had to pull the car over so she could stomp around. Oh, she was pissed!”

Williams had declined to participate in any debates with Ann. He didn’t need to. But they scheduled a joint appearance before the Dallas Crime Commission in early October. Williams’s handlers had publicly distanced themselves from their candidate’s blunders a number of times, but according to the Dallas Times Herald’s Ross Ramsey, while the rape joke and other sexist cracks were totally consistent with who he was, the handlers put him up to a stunt that was out of character. Although Williams bragged about his fistfights with men, his code of honor demanded chivalry in encounters with women. But with cameras all around them, he punched a friend’s shoulder and said, “Watch this.” He walked up to her and declared, “Ann, I’m here to call you a liar today. That’s what you are. You lied about me. You lied about Mark White. You lied about Jim Mattox. I’m going to finish this deal, and you can count on it.”

“Well,” she drawled. “I’m sorry you feel that way about it, Clayton.” She had extended her arm for the ritual handshake and was so surprised that she just left her hand out there. He turned away and snapped, “I don’t want to shake your hand.”

Chris Hughes, the young travel aide and carrier of Ann’s purse, had seen her in emotional and psychological despair following the screaming press gantlet she had to run at the Dallas primary debate. Now he and McDonald were in the van riding away from this episode. Chris was shocked when she looked back over the seat and said, “Boys, this sucker is over. He must have lost his mind.”

To Ann, the turning point wasn’t the joke about the rape, or the story about getting serviced in whorehouses, or the boast about roping her and dragging her in the dirt. It was that image that could never be erased of a grown man aggressively refusing to shake a woman’s hand.

Bill Kenyon, a Williams spokesman, had told the New York Times the candidate was aware of the damage he was doing to himself, well before the handshake incident—an indication that he was getting conflicting advice. “He’s going through this inward-looking process of saying to himself for the first time that politicking is a ton of grief. . . . Instead of sliding around in the muck the way we have been lately, we decided to take a break, start over, and try to come out like in the good old days.”

But that was a hard pivot to make. Ann had claimed that she was closing in the polls, and on camera Williams was shown giggling, “I hope she hasn’t started drinking again.” Then Richards put up a negative campaign ad that showed him saying that over and over. Molly Ivins provided her completely biased view of the race in a Dallas Times Herald column that later appeared in her book Molly Ivins Can’t Say That, Can She? (1991).

But the polls still showed Williams ten points ahead, then seven points ahead. The Richards campaign was praying for Williams to screw up again, and he cheerfully obliged. Williams’s people had to sagely dodge all requests for a debate, since Williams knew almost zip about state government, but two Dallas television stations, KERA and WFAA, managed to rope him in to “in-depth” interviews. He gave a shaky performance, his ignorance more visible than usual. Then one interviewer asked, almost as a throwaway, “What’s your stand on Proposition One?”

“Which one is that?” Williams inquired.

“The only one on the ballot.”

He was still lost, so the interviewer told him what the proposition was about—concerning the governor’s power to make late-term “midnight” appointments. Williams still didn’t know if he was for it or against it.

“But haven’t you already voted?” inquired the interviewer. “You told us you voted absentee. Don’t you remember how you voted?”

“I just voted on that the way my wife told me to; she knew what it was,” Williams explained.

He was so clearly a candidate in a world of trouble, the clip made the national news. The polls showed her within three points.

Ann’s crowds were enormous now, and the rallies had taken on the air and tone that this was a cause, not just another race. Almost too late, Ann had become the campaigner that people had envisioned when she made that speech in Atlanta. In her speeches, she kept going back to an image that had inspired her since 1982, in her first race for treasurer. She had gone to the Rio Grande hamlet of La Joya and a gathering for old folks called Amigos del Valle. Put on by her friend Billy Leo, who owned the general store, the occasions resembled Meals on Wheels, except the old friends and kinfolks gathered for fellowship as well as food. They played dominos and did needlework. Ann had made the scene the endnote of Straight from the Heart. She compressed it in her speeches, but it always came out more or less the same.

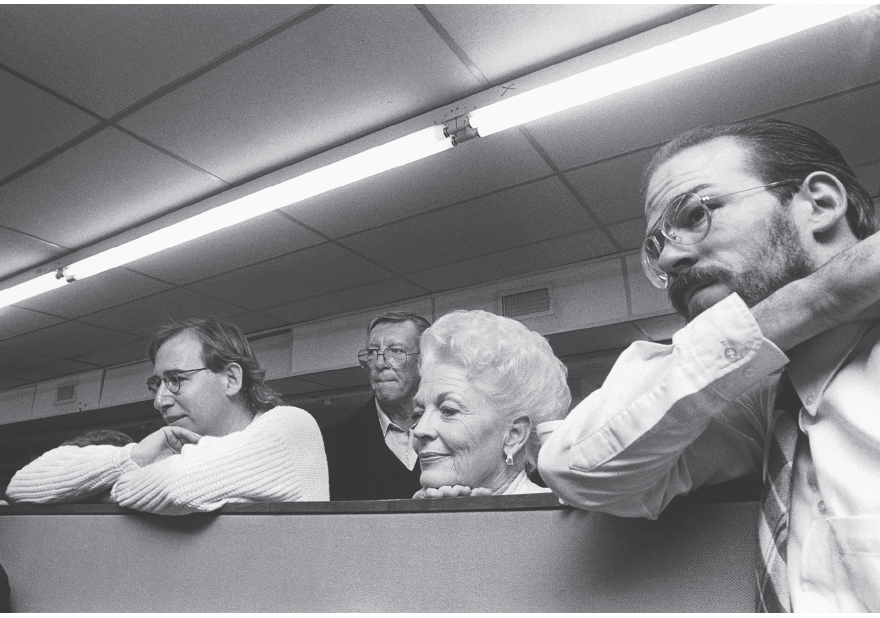

Holding a cup of coffee and an issue of the local newspaper, Ann is greeted by Democratic supporters in the Big Thicket town of Kountze, 1990.

It was late afternoon by the time we were going to leave, kind of dusky on the highway. And as we were pulling away I saw a little woman, she couldn’t have been over four and a half feet tall, probably in her early eighties, standing by the highway waiting for her ride. She was a frail woman, in a cotton print dress that hung straight to her ankles.

I really thought, looking out that window, that that little woman is what our business of public service is all about. She has faith in us to do right by her and by the place where she lives. She will never know the intricacies, the machinations, the pull and tug and hardness of politics, and it doesn’t matter. What she does need to know is that there are people serving in public office who care about her and her community. That’s all she needs to know. And it’s important that we be true to her . . .

She had a mask. She was standing in front of Billy Leo’s store wearing my face. I waved at her. She waved back.

Bud Shrake’s coauthored book with Barry Switzer, Bootlegger’s Boy, had spent nine weeks on the New York Times best-seller list. But a sportswriter who covered Switzer’s career for the Dallas Times Herald and Oklahoma City’s Daily Oklahoman took sharp exception to a chapter alleging that the reporter had participated in an attempt to entrap an Oklahoma Sooner in a cocaine sting. Calling the chapter “vindictive fiction,” he sued Switzer, Bud, and their publisher for libel, slander, invasion of privacy, emotional stress, and loss of consortium. Bud was irked at having to sit for depositions in the suit, which was eventually settled, as they waited for the election.

My dear Bud,

I hate the answering service and don’t leave messages because I’m not here enough to get a return call.

Polls are even. I’m in a snit. I can handle real crisis but good news threatens me.

The only thing I have worth reporting was a press conference in the metropolis of Fannett.

It took place in a feed store and they built a podium out of eight sacks of mule feed.

I’ll miss Jap and Phyllis’s party. I’m in South Texas with Henry Cisneros.

Light candles. Say mantras.

Love, Ann

On the last weekend of the race, a bombshell burst. The Williams team had arranged an old-style whistle-stop train tour, and in his beloved Aggie town of College Station, Williams was pestered by reporters with questions about his tax returns. “I’ll tell you when I didn’t pay any income taxes was in 1986,” he volunteered. “When the whole economy collapsed.” He was being honest, as he often was in making big mistakes. He went on about how the oil bust cratered the entire Texas economy that year, forcing him to sell off companies and fight to stay out of bankruptcy. It was true that his losses far exceeded his income, so he owed no income taxes when his accountants got through with that year’s return. But that was not how the story was bound to play in the press.

Reggie Bashur, a publicist for the campaign, said that one of their efforts at damage control was to open the bar early for the reporters on the train, which was racing toward the Mexican border. They wanted to get those folks good and drunk and out of the reach of their editors. According to Molly Ivins, they even went so far as to cancel the reporters’ Laredo hotel reservations and put them up in Nuevo Laredo, where they would have no telephone service to the United States. “Oh, my God,” Mary Beth Rogers giggled to Dorothy and me the night the story broke. Cathy Bonner put together a campaign spot, Monte Williams provided the voice-over, and aides all over the state were racing to hand deliver the tapes to station managers and get them on the air.

Bud knew that now was the time he needed to come out of hiding and join her. In a fax, he proposed that he accompany her to another event hosted by Willie Nelson. She replied:

Bud m’dear. Don’t know if we will connect by phone. I would love to have you take me to the Willie event tomorrow night. . . . Clayton Williams lost his cool today—big time. You’re still #1. Ann

Then almost in the next breath, it seemed, she sent him a fax full of weariness, hesitation, and uncertainty. She was laying herself wide open.

Nose to nose: Ann Richards and Clayton Williams did not have a formal debate in their race for governor in 1990, but in Plainview that May Ann challenged the rancher and oilman and told him to pull down radio ads that questioned her patriotism.

Dear Bud,

It is almost midnight. Long day. Texarkana, Longview, Nacogdoches, Richmond, Angleton and Houston. Pay dirt today—Williams says he didn’t pay income tax in ’86. We’ll see if it plays big . . .

It would be a treat for me to have you in the mayhem of election night. I’ll be home in the afternoon on election day. Call and we’ll plan.

Some of the kids and I are going to Padre Island after the election. Depending on the outcome I’ve been thinking about asking you to come for some part of the time and have feared that we might not like each other with constant exposure. Does that make sense?

I know that the root of it lies in the lingering anxiety I have about rejection. . . . The fatigue is invading my brain and this probably makes little sense but there won’t be time to write from here on. I’ll be home again Sunday night late.

It’s great to come home to your fax notes.

Fondly, Ann

Bud later told her that he would be glad to join them at the beach, and would bring his sleeping bag, but for now, with a metaphor that mixed Texas hooey with a line from the Beatles, he emphasized that she had really scored this time.

Dear Guv:

Great going! I’m proud of you!

Keep pounding the little cowboy with that big Silver Hammer.

Don’t let him get away with confusing his business losses with his personal income.

I was surprised to see you paid such a high percentage of income tax in ’86.

I wonder how many billionaires paid 30 percent taxes?

None, I’m sure.

I could have fixed you up with my CPA and he would have saved you from paying the IRS anything in ’86. Of course, you would now be a fugitive.

I’m praying harder than ever . . .

I’ll see you Tuesday. Get someone to tell me when to show up and where.

Love, Bud

On election night, the Democrats’ coordinated campaign made the Hyatt Hotel in Austin its headquarters. In one large ballroom, anxious faces and gulps of booze prevailed as the returns came in. Handsome Rick Perry, who proved to be no upstart, was edging ahead in the race for agriculture commissioner. With 99 percent of the precincts reported, Perry had 49.1 percent to 47.9 for Jim Hightower, ending the colorful populist’s career in electoral politics. The office they sought had little relevance in the lives of most Texans. It was a historic race because one liberal Democrat’s downfall was matched by the ascent of a conservative, newborn Republican who would never lose an election in Texas, and with much initial fanfare and subsequent flameout he would one day seek the presidency. Karl Rove had schooled Perry in his breakout campaign. He also guided Kay Bailey Hutchison to a win in the treasurer’s race. The time would come when his two protégés couldn’t stand each other.

In the lieutenant governor’s race, Bob Bullock had bluffed, bullied, and out-hustled two attractive, younger opponents. McNeely and Henderson wrote that for almost three years he had run like a man possessed. The first credible challenger was a Democratic state senator, Chet Edwards. Mark McKinnon had worked for Edwards before signing on with Ann Richards. Bullock raised nearly twice as much money as Edwards did, and lined up an intimidating list of endorsements of elected officials. At the last moment, Edwards decided to run for a vacant seat in the U.S. House, which he won. “Thank God,” McKinnon joked to McNeely. “It saved us from having Bullock tear off our heads.”

George Christian, the veteran consultant who had been Lyndon Johnson’s press secretary, was close to Bullock, and he feared the comptroller might underestimate the GOP’s Rob Mosbacher, Jr., who grew up close to the Bush family; to burnish his governmental credentials, Bill Clements had appointed him chair of the Texas Department of Human Services. Christian urged Bullock to hire Jack Martin to run his campaign. He argued that bringing in Martin, who had run Lloyd Bentsen’s campaigns, would signal Bullock’s alignment with the party establishment. Bullock consented to a meeting, and then, to Christian’s astonishment, he tore into Martin. Christian said Bullock “chewed Martin out worse than I ever heard a man chew out another man.” Consider for a moment: that came from a man who had witnessed LBJ’s tantrums.

But that was often Bullock’s perverse way of measuring a new acquaintance. He hired Martin to run the campaign. Geared up for a vicious fight, Mosbacher ran an ad with a photo of “old Bob Bullock,” who wore a hearing aid, with his hand cupped behind his ear. Bullock countered with taunts of “Little Lord Fauntleroy” and an ad with a soft-looking child moving to knock down a sand castle as a voice-over blamed Mosbacher for a $340 million budget shortfall at the agency he chaired. Bullock’s ads blamed Mosbacher for oil spills in the Gulf; the only basis for that was a barge company owned by the Republican’s father. In the end, Bullock won the heated duel by 260,000 votes, a majority of 51.7 percent—and 75,000 more votes than Ann Richards received. Everyone said the lieutenant governor in Texas had more power than the governor. And Bullock had the votes to start proving it.

The morning of Election Day, a former county judge from West Texas named Bill Young was holding down his job in the veterans programs division of the General Land Office. The judge and others liked to hang out in the speechwriters’ office, because we closed the door when we wanted and we didn’t mind them smoking in there. Dorothy was pretty confident that she would be on the governor’s staff if Ann won, but she would be jobless if her boss lost. Young told us he always consulted a favorite barber on the morning of important elections, and in the course of our jitters during those hours when nothing about an election is known for sure, he walked in, took off his cowboy hat, and told us the unscientific polling result was in. Jim Hightower and the Democrats’ treasurer candidate were in trouble, the barber figured, but he said that when he got in the voting booth and started to vote in the governor’s race: “I looked at that ballot, and the face of that ignorant son of a bitch just swum up at me.”

Clayton Williams’s election-night affair was by invitation only, and when he came down to concede, a torrent of catcalls and slurs erupted when he spoke Ann’s name. It angered him, and he snapped, “Now . . . now . . . you owe me that courtesy!” The rich old-boy establishment in Texas was coming apart on live television; the candidate was having to shout down his own supporters.

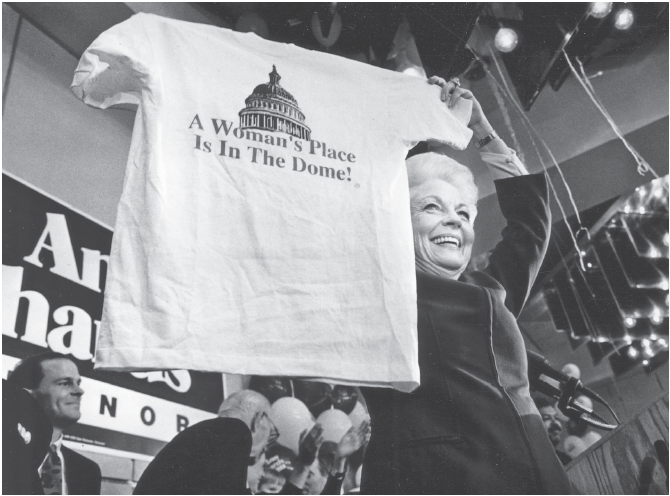

A short time later, Ann climbed on a stage and in exultation jammed her fist high in the air. She grinned and held up a T-shirt with an illustration of the Texas Capitol with the caption “A Woman’s Place Is In the Dome.” The explosion of noise was deafening. On the floor beneath the new governor, I saw Cinny Kennard, who had been one of the leaders at the mauling of Ann after the Dallas debate—the reporter we called the Red Dress. For the occasion, she again wore red. She looked forlorn and lost.

From left, Richards aide Don Temples, Bud Shrake, Ann Richards, and her son Clark Richards watch the returns in the race against Clayton Williams. Austin, 1990.

The newly elected governor of Texas holds up for her joyous supporters a T-shirt that became ubiquitous in the final days of her 1990 campaign.

The next morning, the Dallas Times Herald headline declared, “Ann Whups Him!” True enough, but it was no landslide. A Libertarian candidate denied her a majority; she finished with 49.6 percent of the vote. But 99,239 more Texans believed the liberal grandmother from Austin made a lot more sense than the conservative Midland oilman and cowboy. Many of her voters were middle-class women who couldn’t wait to get to the polls and send that perceived yahoo back out to his pipelines, whirlwinds of dust, and creosote bushes. Ann had come from a long way back and run a stellar finish, but she also benefited from one of the most spectacular self-destructions in Texas political history. Williams had spent approximately $22 million, including $8 million of his own money. He was no ignorant fool—he was just out of his element. “I’d shoot myself in the foot,” he later reflected, still with that infectious grin. “Then I’d load ’er up and blast away again.”

Jim Hightower’s concession in the Capitol the morning after the election was short and sad but good-natured. He described his feelings sagely: “One day you’re a peacock, and the next you’re a feather duster.”

When Bob Bullock made his appearance in the Senate chamber, John Sharp, the new comptroller, and Dan Morales, the new attorney general, were eager to stand close to his side. Sharp presumed to give the smaller man a friendly hug. Bullock’s expression went ice cold.

Ann also held her press conference in the Senate chamber. The room was packed as she slowly made her way through the applauding crowd. It was a cold day, and most of the people were bundled up in coats. The crowd of reporters around the microphone tried to back up and give her room, as if in recognition of her revised status. In the front of the pack was the Houston Chronicle’s dark-haired, mustachioed R. G. Ratcliffe. He had been laughing with us as hard as Ann and Monte Williams and everyone else that first night at the beer and fish joint on the boat trip, but he had gone after Ann and other elected officials with skill and doggedness that was unmatched by his colleagues in the Capitol press corps. Ann threw her head back on seeing him, they traded smiles, and she said, “O ye of little faith, R. G.”

That week, Bud Shrake had promised to attend a Fort Worth reunion at his alma mater, TCU. Once more at an important time he was away from her. Ann’s fax read:

Dear Bud,

The crown got heavy today. No list of things that must be done. No hourly frenzy. I tried some Christmas and inaugural shopping for the family but I could not get much done for shaking hands. I feel trapped in the house and outside too. All of this will take some getting used to—and I am a little frightened.

Just got back from the Claus and Sunny von Bülow movie and it was surprisingly good. I went with my friend Pat Cole—another manifestation of my weird state of mind is that I don’t feel like I have anything to say—even to old friends. I’m tired of talking about the race. Transition talk spurs gossip or breaks confidences and I think I am tired of being entertaining.

I’d love to go to the movie Sunday. What time shall I expect you? I only wish it was not such a long time until then.

Maybe I’ll clean out some closets.

Love, Ann