The topic of Reverend George W. Allison’s sermon at the First Baptist Church in East St. Louis for the first Sunday in June was “The Race Problem.”

“God has no pets,” Allison proclaimed in a plea for racial tolerance. But the tough, crusading preacher also suggested that the races, at least for the time being, should live and work and study and marry and worship apart. He intoned, “The black man never had a chance until he was set out on his own initiative. It was separate schools that produced Booker T. Washington … The attempt to equalize the races is a sin against both the black and white man.” The sermon, coming from a rare voice of moderation and tolerance in East St. Louis, suggests what small steps even the supposed racial liberals of the time were willing to take to gain racial peace.1

Meanwhile, East St. Louis labor leaders had sent a telegram to the Illinois Council of Defense, the state’s civil defense overseer, arguing that the racial situation in East St. Louis threatened war industries and should be investigated. Two members of the council’s labor committee and a staff counsel came to East St. Louis for hearings on June 7 and 8. They interviewed dozens of witnesses, including city officials, policemen, black leaders, white industrialists, and several unemployed black men who had recently come to East St. Louis because they had been told there were jobs to be had.2

In its report, the committee attributed the riot on May 28 to “the excessive and abnormal number of negroes” in East St. Louis. “There was resentment that the colored people, having overcrowded their quarters, were spreading out into sections of the city regarded as exclusively the precincts of the white people. The colored men, large numbers of whom had been induced there and who could find no jobs, in their desperate need were … threatening the existing standards of labor.”

The committee charged that there had been “an extensive campaign to induce negroes to come to East St. Louis … a campaign [that] required considerable financing,” including “extensive advertising” in Southern newspapers “setting forth the allurements in East St. Louis in the way of abundant work, short hours, and high wages, good conditions and treatment.” Labor agents, the committee reported, “were also shown to have been very active in the South,” sending black men North by rail. “At convenient points these agents would leave the car with the remark that they had telegrams to send, or would get lunch. They never came back, and the train pulled out without them. The negroes were thus left to shift for themselves upon their arrival at East St. Louis, to find work as they could and quarters as they might.”

Although the committee stopped just short of definitively stating who was behind this anonymous campaign to import blacks to East St. Louis, it observed that “during the previous year there had been industrial troubles in several of the plants of the city,” and took note of allegations by witnesses “that employers had brought about the extraordinary influx of colored men to have a surplus of labor and thus defeat the contentions of their employees.”3

The attacks on blacks in the streets of East St. Louis that had intensified into a small riot on May 28 continued in June. Police stopped one such assault, let the whites go, and arrested three African Americans for carrying concealed weapons. An old black man was beaten almost to the point of death by a gang of young whites after he allegedly refused to give up his seat on a streetcar to a white woman. He staggered to a nearby firehouse, where police had to rescue him from a mob of several hundred whites. Black strikebreakers were beaten outside the aluminum plant so regularly that, toward the end of June, national guardsmen were ordered to escort black workers on the night shift back and forth between work and home.4

Strife between labor and management intensified across the city. Both the streetcar workers and the retail workers went out on strike. But street crime was down, at least for a few weeks. With hundreds of troops in town and the police on alert and under orders to brook no nonsense, criminals, black and white, were laying low. On June 15, the Journal gave big play to the story of a black robber who had held up a white man, noting that this was the first such occurrence in the two and a half weeks since the May riot. But rumors continued to spread through the white population that blacks were buying guns and were preparing to storm white neighborhoods and slaughter whites to exact revenge for the assaults of May 28.

Some blacks were buying guns, despite the mayor’s ban on East St. Louis gun and pawnshops from selling weapons to African Americans. Policemen and national guardsmen stationed at the bridges from St. Louis would regularly stop blacks coming into East St. Louis and confiscate any weapons they found. Whites were waved on through, and a few very light-skinned blacks supplemented their income by buying several guns a week in St. Louis and passing for white as they toted them across the Free Bridge. Black funeral homes with hearses traveling between the two cities sometimes stashed a few guns in coffins. Still, despite a public statement by Mayor Mollman that “colored people … had made no individual retaliations to defend themselves,” the rumors of black aggression against whites persisted. Blacks tried to avoid giving the impression that they were plotting aggressive action. For example, since 1909 the local black chapter of the Odd Fellows lodge had held weekend parades in military formation on Bond Avenue, wearing lodge uniforms and carrying ceremonial swords, but without guns. The rumor spread that Dr. Leroy Bundy, who lived on Bond Avenue, was drilling the Odd Fellows for battle in the streets. After the May 28 riot, the parades ceased.5

Still, Thomas G. Hunter, a black surgeon, recalled, “Things grew worse and worse. The colored people were greatly terrified. We sent committees to … the governor, to the mayor. Some of us went down to see the mayor, and the mayor’s secretary, Mr. [Maurice] Ahearn, stopped us and asked us what we wanted.” Hunter told Ahearn that he and assistant county supervisor Dan White, a black man, recently had been stopped at the Free Bridge by soldiers armed with rifles and told to put their hands in the air. While the soldiers were searching them and poking through the tool box in Dr. Hunter’s car, an automobile passed by carrying two large trunks. The car, driven by a white man, was waved through the check point.

“Why don’t you search that?” Hunter had asked, lowering one hand to gesture at the passing automobile. “It looks more suspicious than I do.”

A soldier poked him with a rifle and snarled, “If you don’t shut up your beefing, I’ll fill you full of lead.” Hunter thrust his hands high and kept his mouth shut.6

Early in June, a committee headed by Bundy and Dr. Lyman B. Bluitt responded to telephone calls from the Central Trades Labor Union and met with the regional labor organization. The union leaders, including Earl Jimmerson of the meat cutters, wanted to talk about organizing blacks. A biracial committee was appointed to look into the matter, but nothing was done beyond that. Bundy and Bluitt also warned Mayor Mollman, whom they had supported for reelection, that eventually some black man would get mad enough to retaliate against white attackers, and perhaps trigger a riot, unless the police stopped standing by while whites assaulted blacks. The mayor said he was surprised to hear their concern—he thought relations between the races had improved considerably since the end of May. But he told Bundy and Bluitt that their complaints would be thoroughly studied. He called in police chief Ransom Payne, who furiously denied that his officers were practicing any favoritism and insisted the police were doing a fine job of enforcing the law with an even hand.7

As spring crept toward summer, tension between the races in East St. Louis tightened even more, like a powerful spring under increasing pressure. At Fifteenth Street and Boismenue Avenue in Denverside, a neighborhood blacks had been moving into in recent years, three white national guardsmen in their summer dress khakis overpowered a city detective, stole his service revolver, and went on a rampage. They already were carrying Army 45s, and with their impressive arsenal they robbed three black men at gunpoint and wrecked a saloon in a black neighborhood after drinking a considerable amount of the whiskey on hand. Outside the saloon, they were subdued by police and national guardsmen before, as the Journal put it, “They started a race riot.” The three young men were said to be from wealthy Springfield, Illinois, families.8

At the beginning of the last week in June, attorney Maurice V. Joyce introduced a resolution to the chamber of commerce urging companies to stop importing blacks to East St. Louis and calling on city officials to “employ every legitimate means to prevent the influx of negroes into East St. Louis, and thereby take every precaution against crime, riot and disorder.” The resolution was tabled.9

As attacks on blacks increased, a committee of blacks headed by Dr. Leroy Bundy went to the mayor again asking for help. Once again, the mayor tried to calm them, saying things were not as bad as they thought. On June 28, the aluminum workers’ strike whimpered to an end. The number of pickets had dwindled, at times, to a handful. A union spokesman said the strike was being called off for “patriotic” reasons. Very few of the strikers were ever rehired.10

Meanwhile, as the Post-Dispatch’s relentless Paul Y. Anderson reported, East St. Louis had once again stopped enforcing Sunday closing laws as well as the ordinances against prostitution and gambling. After the Reverend George W. Allison, a source for Anderson’s stories, complained to Mayor Mollman about growing lawlessness, the minister was summoned to a meeting with Mollman and political baron Locke Tarlton at city hall. Mollman shut the door to his office and the three men talked for three quarters of an hour. Allison said he felt that he had been betrayed after working hard to get Mollman elected, and, his anger building, mentioned by name a bar owner who was illegally open on Sunday, selling drinks and, it appeared, the services of prostitutes. Allison said he had confronted the man and told him he was going to report his activities to the mayor, and the man had laughed and said the mayor already knew all about it and had no intention of honoring his campaign promise to enforce Sunday closing laws.

Tarlton sighed deeply and said, “Reverend, the trouble about it is, the damn city is just like it has always been.” The mayor heaved himself out of his well-cushioned desk chair and said, “Locke, you don’t mean that?”

Tarlton replied, “Yes, mayor, it is just like it has always been.”

“Why Locke,” said the mayor, “didn’t I run those penitentiary birds out from the rear of the police station here?”

Tarlton laughed and said, “Yes, mayor, you ran them out of here, but they are still in town. Your old friends are all here, mayor, they are all here.”

And Mollman, his long, thin face and balding scalp turning red from barely stifled laughter, sat back down and said, “Well, I’ll be damned if I don’t believe I’ll join the Third Artillery and go to France.” Tarlton and Mollman shared a long, hearty laugh.

Allison, a tough, righteous Texan who had seen a lot of sin in his life, ended the meeting by telling Tarlton he had five days to close down one particularly notorious “hotel” or Allison and his supporters would shut the place down themselves and nail the door shut so no business of any kind could be conducted there for a year. “If you don’t clean this town and get rid of this idle thug crowd you’ve got here,” he said, “you will have a riot here one of these days and that little thing you had in May will not be a patching.”11

As summer arrived, East St. Louisans stayed in the streets later and later. Even without daylight savings time, darkness didn’t fall until about eight o’clock, and by then the temperature had usually gone down to the low eighties. Holdups increased, and so did assaults on blacks. But blacks in East St. Louis had not retaliated for the frequent attacks on them.

On Sunday, July 1, the temperature hit ninety-one degrees at ten in the morning, and hovered around ninety until late afternoon, typical of a summer day in East St. Louis. The air was blanketed with moisture, as usual. The coming together of the Mississippi and the Missouri, the two largest river systems in America, cranks up the humidity that hangs palpably in the miasmic summer air of St. Louis and East St. Louis.

Out-of-work white men had taken to hanging out near the eastern end of the Free Bridge, harassing blacks verbally and sometimes shoving and hitting them. The crowd of whites was larger than usual that Sunday, perhaps in anticipation of the Fourth of July. The whites drank, boasted, and flourished guns—many East St. Louisans of both races routinely fired guns into the air in lieu of fireworks to celebrate the Fourth. Some blacks who were unlucky enough to be caught alone at the East St. Louis end of the Free Bridge were beaten. Reports of the beatings quickly spread to the black neighborhoods a few blocks away, adding strength to a rumor that whites planned on killing everyone—men, women, and children—at a black Fourth of July celebration in a city park in the South End. A similar rumor—blacks were planning to attack white Independence Day festivities—spread among whites.

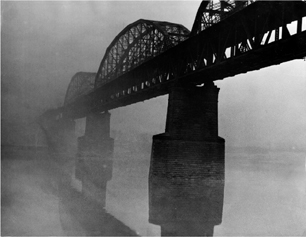

The Free Bridge facing east

About seven o’clock Sunday evening, in a South End neighborhood near Tenth and Bond Avenue—the intersection near the approach to the Free Bridge was a focus of black street life—a black man was attacked by roving whites. He pulled a gun and fired, possibly wounding one of his attackers. The story of the shooting, much magnified by rumor, made its way into both the black and the white communities. Shortly after that, a black woman in the same neighborhood ran crying hysterically onto Eleventh Street, where a group of black men stood at a corner waiting for the cool of the evening finally to descend. The woman screamed that she had been attacked by three white men a block to the west. “Let’s go to Tenth Street,” a black man shouted.12

About the same time, black plainclothes policeman John Eubanks reported to duty at police headquarters and saw a white railroad security officer with three men in custody—two white, one black. “I want them booked,” the security officer told the police lieutenant in charge. “This negro was running and these two white men were running after him up the railroad tracks.” It turned out the two white men had been in the vanguard of a mob of fifty or more chasing the black man through rail yards near the Free Bridge. The lieutenant asked the white prisoners what had happened and they said the black man had insulted them and they had hit him in retaliation and he had taken off running. The lieutenant told the black man to go home and ordered that the two white men be held and booked. Normally, a booked suspect was held at least overnight, but Eubanks checked later and found out the white men were released and back on the street by ten thirty P.M.13

A little after nine P.M., a veteran black policeman named W. H. Mills finished a relatively uneventful twelve-hour shift in the northern part of downtown and took a streetcar out to Seventeenth and Bond on his way home. A couple of black men he knew asked him what the trouble was downtown. None that he knew of, said Mills. One of the men said with agitation, “Why, two colored women just came by and said that the white folks down at Tenth Street and the Free Bridge were rocking every nigger they could see.” Mills gathered some details and ran across the street to a garage that had recently been opened by Dr. Leroy Bundy, who operated several small businesses in the neighborhood, and used the telephone to call police headquarters. He reported that whites, some of them drunk, were attacking blacks and pulling them from automobiles around Tenth and Bond. Then he walked to his home on Market Avenue and went to bed.14

Later that evening, nearby on Bond at Nineteenth Street, the day’s last services ended at St. John American Methodist Episcopalian Zion Church. A bishop from St. Louis had given a guest sermon. Dr. Thomas G. Hunter, who lived across the street from the church, saw the bishop outside the church and offered to drive him back to St. Louis. Two other men, a minister named Oscar Wallace and a teamster named Calvin Cotton, came along for protection: Hunter had heard of the attacks near the Free Bridge, and he was concerned for the bishop’s safety. While they were across the river, they found out later, a black Model T Ford full of white men had sped through their neighborhood firing into houses. The streets in that part of town were unpaved or in poor condition, and Model T Fords have minimal suspension systems, so the car would have bounded down the street from pothole to pothole, with the men firing wildly, unable to aim. But if the purpose was intimidation, it didn’t really matter what they hit—homes, cars, people.

They also found out that some of the men who had lingered in front of the AME church, holding on to the evening, heard the shots about a block away and went home and got their guns.

Hunter, Cotton, and Wallace made the trip back and forth across the river without incident, and returned to the neighborhood after eleven thirty. A couple of blocks southeast of the AME church, Dr. Hunter stopped at Twentieth Street near Market to let Cotton off at his house. As they were standing on the street, chatting about the evening, a black automobile—Hunter could not ascertain the make—sped up from the south on Twentieth Street with its lights out, made a screaming left turn, and headed west on Market. As it accelerated, men leaned out of both sides of the open car and fired into the houses on either side of Market.15

At his home at 1914 Market, black lawyer N. W. Parden was awakened by a fusillade of gunshots that sounded “like firecrackers popping.” He ran out into the yard in his pajamas in time to see a carload of white men firing with pistols. Then he heard the crack of rifle fire and the boom of shotguns. Although he could barely see anyone in the shadows, it was clear from the flashes of light from either side of the street that blacks along Market Street were returning fire. The white men stopped shooting as the car sped west into the darkness.

Parden’s next-door neighbor, policeman W. H. Mills, was exhausted from his long shift and was pulled from a deep sleep by the gunfire from the street. Urged by his wife to get out of bed and see what was going on, he ran to the front door. Parden was standing in the front yard with a pistol in his hand, and a young man named Harry Sanders who lived nearby shouted that a car had gone through full of men shooting guns—“a gang of white fellows,” Sanders said.16

Mills immediately thought of the brutal beatings of blacks on May 28, and the fires that had been set. He was worried about his wife—she was sick in bed—and he was afraid she wouldn’t have the strength to escape if a mob of whites attacked. He wasn’t sure what to do, but finally he went back in the house and lay down next to his wife. A bit later, he heard what sounded like a gun battle somewhere in the direction of downtown, but the carload of nightriders did not return to his neighborhood—probably got scared off, he thought, with some satisfaction—and he finally drifted into a fitful sleep.17

A block away on Bond, Dr. Hunter and Reverend Wallace, who were next-door neighbors, were too jittery to go to bed so they sat on Hunter’s darkened front porch and waited nervously to see if anything else happened. A little after midnight they saw flashes of light from the west, toward downtown, and heard a long, sustained volley of shots. For a moment, it sounded as if a war had started. Then the firing stopped, and left an ominous hole in the night. They went into their houses and locked the doors.18

Shortly before midnight, police began receiving reports that armed black men were assembling in the South End. Night police chief Con Hickey was on the phone talking to one of the callers when another line rang and cub reporter Roy Albertson of the St. Louis Republic picked up the receiver. A grocer named James Reidy, who lived on Eighteenth Street south of Bond Avenue, said more than a hundred armed blacks had gathered in his neighborhood, summoned by a church bell. “It’s ringing now,” the grocer said. “If you listen, you can hear it.”19

Albertson, who was only eighteen years old, couldn’t hear any bell. But he sensed a story, particularly after the grocer—thinking he was talking to a policeman—added, “If you get some men down here right away you can disperse them before there is trouble.” Albertson passed the report on to Con Hickey. Earlier phone calls reporting blacks being beaten and shot at and pulled out of their cars by whites had elicited little or no official reaction, but this time it sounded like the long-rumored armed black rebellion had finally begun. Hickey told two plainclothes detectives, Samuel Coppedge and Frank Wodley, to “get out there and see what’s going on.”20

Coppedge, who was playing gin rummy with Robert Boylan, a Globe-Democrat reporter, laid down his cards and he and Wodley headed to their assigned car, an unmarked, black Model T Ford. The Ford was just like at least one other car that had recently driven through black neighborhoods in the South End carrying white gunmen firing into homes. Wodley and Coppedge were hoping to get their business over with by one thirty A.M., when their shift ended and they could go home. Albertson asked Coppedge if he could ride along. The detective nodded.

The two detectives, in summer suits and straw hats, sat in the front with the driver, police chauffeur William Hutter. The forty-nine-year-old Coppedge, a sergeant, was next to the door. His twenty-nine-year-old partner, Wodley, sat in the middle. Two uniformed policemen, Oscar Hobbs and Patrick Cullinane, sat in back. The top was up. The car was crowded with bulky men, and Roy Albertson stood on the running board on the driver’s side, holding on to the door. The farther they got from the heart of downtown, the fewer streetlights broke the darkness. The temperature had dipped into the upper seventies, although the high humidity persevered, as usual.21

The police car headed east to Tenth and then turned south through a predominantly black area close to white neighborhoods. As the police car reached Tenth and Bond, the driver slammed on the brakes to avoid plowing into a mob of black men who were dimly lit by the weak headlights of the Ford. The mob parted as the car came to a halt, and most of the men ended up on the sidewalk near the passenger side of the car, where Coppedge sat. There was no streetlight within fifty feet of that spot.22

Albertson later recalled that, in the dim light, he could see that the black men were heavily armed with revolvers and automatic pistols, rifles and shotguns. Some held large sticks or clubs. There were 125 to 150 of them, Albertson said, mostly young men, some in their teens. The men, it turned out, were headed toward the Free Bridge, where several white men working at a service station had beaten a black man with no apparent provocation. But Albertson and the police did not know that.

Albertson, Cullinane, Hutter, and Hobbs all later testified that Coppedge identified himself as a policeman and exchanged words with the men. In Albertson’s version of the confrontation, Coppedge yelled out the window, “What’s doing here, boys?” and someone shouted in reply, “None of your damn business.” Coppedge said, “Well, we’re down here to protect you fellows as well as the whites. We are police officers.” Someone shouted at Coppedge, “We don’t need any of your damn protection,” and the crowd began guffawing.23

Coppedge, according to Albertson, turned to the driver and said quietly, “Let’s get the hell out of here.” The driver put the Ford in gear but he hadn’t traveled more than a few feet when there was a loud, explosive pop. Albertson was not sure if one of the tires had blown—tires were always blowing on Model T Fords—or if someone in the crowd had fired a shot. In any event, Albertson said, the explosion triggered a volley from the black men. The front tires blew flat, then the rear ones, and the bullets kept coming, punching into the metal with loud clangs and pops, shattering the windshield and plowing into the flesh of three of the men in the car. “It looked like they turned loose and tried to empty their guns as fast as they could,” said Albertson, who threw himself down on the wide running board on the driver’s side away from the gunfire as soon as he heard the first bullet. One or more of the policemen may have fired back, but without apparent effect.

The startled driver jammed his foot down on the gas pedal and drove hard into the middle of the crowd, banging men aside as he pushed east down a long dark block of Bond Avenue, running on his rims, with sparks striking from the pavement and metal howling. By the time he had driven to Eleventh Street and the next streetlight, the shooting had stopped. The driver slowed briefly, looked to his right, and said, “Sam is shot.” Coppedge had taken a bullet to his jugular vein and died almost immediately in a spurt of dark blood.24

Coppedge’s partner, Wodley, had been shot in the abdomen, probably more than once, and he was moaning with pain, critically wounded. He died two days later. Hobbs, on the right side in back, had been hit in the right arm. The other uniformed policeman, like Albertson and the driver, remained unhurt. The driver headed for Deaconess Hospital, only four blocks away at Fifteenth and Bond. Just before he got there, he passed a fire station, and Albertson told him to slow down. The reporter hopped off the running board and ran in to call police headquarters.25

Albertson’s call came into the police station at about twelve twenty-five A.M. He reported to Con Hickey that Coppedge was almost certainly dead, and Wodley was gut-shot and dying. And he said a mob of black men, “armed with everything in the way of portable firearms,” was heading for downtown. The general feeling around the police station, Boylan recalled, was that the mob had already killed a couple of policemen, and they were heading for the station to kill some more. Instead of rushing out to confront the mob, the handful of police on duty at that hour on a Monday morning stayed at the station to protect it and the adjoining city hall. Hickey called Mayor Fred Mollman, who was already awake. A machinist named Fred Peleate had called him about twelve thirty to report that a policeman had been shot on Bond Avenue near his house. The mayor got dressed and headed downtown.26

Meanwhile, on Missouri Avenue about a block from the police station, at the YMCA, director W. A. Miller was awakened by the sound of a car skidding to a stop in front of the Commercial Hotel across the street. The hotel, saloon, brothel, and boardinghouse for hoodlums was managed for New York absentee landlords by political moguls Thomas Canavan and Locke Tarlton, and its denizens enjoyed a considerable amount of official protection.

Miller got up and went to the window in time to see four white men get out of the car. Two of them stood on the street, pacing back and forth, apparently looking for someone. One of them was walking strangely, as if he had a hurt leg. The other two ran quickly into the hotel. In a moment, another car drove up, with bullet holes in the radiator and the rear. The driver and passengers, Miller recalled later, “looked like a bunch of outlaws. I gathered [from their conversation] that they had been driving through that section of town where the policeman had been shot, and they were fired on by Negroes.”27

Mayor Mollman arrived at the police station between one and one thirty A.M. Boylan was standing out front, between the police station and the downtown fire station, nervously scanning Main Street for the black mob he had heard was coming. Mollman got out of his car and walked up. He said, “Looks awful bad, don’t it?”

“Yes, it does,” said Boylan.

“Do you think we’re going to have trouble?”

“Yes, but you better talk to Roy. Albertson was in the machine and got first-hand information and he can tell you better than I can, but it looks bad to me.”28

By then, Albertson had arrived back at the police station, and he joined Mollman and Boylan on the sidewalk. He gave the mayor a quick summary of what he had seen and said, “As soon as these morning papers get on the streets in East St. Louis you’re going to have trouble. As quick as people find Coppedge has been killed and Wodley is dying … there’s going to be trouble around here. You had better get the troops. You had 600 or 700 soldiers down here on May 28 for that riot. It will take double that number to even try to handle what is going to turn loose today.”

Albertson may have been trying to goad the mayor into saying something interesting, something quotable. The reporter had a two A.M. deadline to get his stories into the St. Louis Republic, a morning paper that was due to hit the streets by five A.M. But Mollman did not say a word. Albertson ran inside the police station and called the Republic, dictating his first-person account to a rewrite man. It would, of course, be the main front-page turn story that morning.29

Boylan had a similar deadline for the St. Louis Globe-Democrat, and his main morning competitor knew a lot more about what had just happened than Boylan did, so he tried another tack. “All right, Mr. Mayor,” he said, “come on over to my office where you can be quiet and we’ll work the telephones.” That way he could listen to the mayor’s calls.

“Well,” Mollman replied, after a moment of thought, “I might as well go to my own office.” Boylan nodded. The mayor left to make some calls. Mollman tried several numbers in Springfield and got no answer before he reached Dick Shinn, an assistant to the adjutant general of the Illinois National Guard. Shinn had been in East St. Louis during the May riot, and he had kept in touch with the situation, although he had been assured by Mayor Mollman that things had settled down. Shinn began calling National Guard officers in towns all over southern Illinois, telling them to assemble troops and head for East St. Louis. By then, off-duty policemen had been called in, and there were about a dozen uniformed patrolmen and several plainclothes detectives—all white—waiting inside the station for police chief Ransom Payne to tell them what to do. More were on the way.

A call came in that a mob of whites had assembled in front of a chili parlor a block or so away, on Collinsville Avenue. Some of the men had been drinking, working up the nerve to storm a nearby building and wreck the dental office of Dr. Leroy Bundy. There was a light on in the window of what they thought was his office, and finally the mob surged across the street, led by a couple of army enlistees who were waiting to be sent to basic training. One of them had a rifle, and he led the crowd up to the second floor and smashed the butt through the opaque glass door to Bundy’s office. There was no one there, but an electric fan was running and a light was on, so they decided the dentist must be nearby and began searching the building. They found no one. A few policemen walked over and broke up the crowd, but some of the men were reluctant to go home. So a small gang milled around in front of the police station for hours, waiting for something to happen.30

At about two in the morning, a neighbor with a telephone knocked on the door of John Eubanks, a black policeman who lived on St. Louis Avenue just north of downtown East St. Louis. She told Eubanks that a policeman had called and asked that he come to the station at once. The woman was unclear about what the trouble was. Eubanks quickly dressed and headed on foot for the police station, just a few minutes away. When he got there and saw a surly crowd of whites milling around in front of the station, he pulled out his badge and pushed his way through, ignoring the curses and threats and racial epithets.

There were about seventy policemen on the East St. Louis force, six of them black. The blacks all worked in plainclothes, perhaps on the theory that a black man in a uniform would offend or outrage the white majority. Inside the station, Eubanks noticed that most of the white policemen were there, but none of the other blacks. A lieutenant told him, with great agitation, “John, Coppedge was killed a short time ago, Sergeant Coppedge. Down in the South End, at Eleventh and Bond.” Eubanks was shocked and saddened. Coppedge was married with a couple of children, one of them now a young soldier training in Florida to fight in the Great War.

“How did it happen?” asked Eubanks.

“He was killed by an armed crowd of Negroes,” was the reply.

“Well, we better get on down in there, hadn’t we?” said Eubanks.

“No, no,” said the lieutenant. “Wait until your boss comes in. I have sent a machine [an automobile] out for the chief of detectives, and he will be here in a few minutes.” Chief of police Ransom Payne was there, too, but he said nothing to Eubanks.

Chief of detectives Anthony Stocker arrived a few minutes later. Eu-banks went up to him but was waved away, and Stocker and Payne went into the chief’s office. The two men spoke heatedly about something, and Eu-banks sensed through the office window that he was among the topics of conversation. At one point, the mayor walked in and joined the discussion. Finally, the chief came out of his office.

“What are we going to do?” Eubanks asked impatiently.

Chief Payne spoke very carefully, watching for Eubanks’s reaction. “Owing to the circumstances,” he said, “it is not safe to attempt to go down in there now with the little handful of men we have. It seems there is a very large body of Negroes armed in there, and it isn’t safe for us to go in.” And that, it seemed, was that. Eubanks was dismayed, but he stopped himself from asking why they had called him in the first place. He walked back home to try and catch a few hours of sleep. He figured he would be busy later that day.31

At about three in the morning, in Springfield, Illinois, Dick Shinn of the Illinois adjutant general’s office phoned National Guard colonel Stephen Orville Tripp. He asked Tripp to come over to his office immediately. Tripp put on a summer suit rather than his colonel’s uniform and hurried to the adjutant general’s office. Tripp was the assistant quartermaster general for the Illinois National Guard, a slight man of late middle age who had been a deputy United States marshal, a policeman, and a deputy sheriff—as well as a lumberyard foreman. One man in the state capital who had seen him in action said sarcastically, “Tripp is an excellent man as an office clerk.”32

Shinn told him that a policeman was dead in East St. Louis and the situation had the makings of a riot. Several National Guard units had been contacted and would be arriving in the city in a few hours. Tripp would be in command of them. Less than two hours later—still in his business suit and carrying only a briefcase—Tripp was on the train to East St. Louis with orders to meet with the mayor and cooperate with him “in the matter of enforcing the law.”33

About four thirty A.M., Earl Jimmerson, the East St. Louis labor leader who was also a member of the county board of supervisors, was awakened by a phone call. It was a white woman he knew in the South End, and she told Jimmerson that Coppedge was dead. Coppedge had been a friend, and Jimmerson was stunned. He went downstairs and opened the front door and was a little surprised to see that the St. Louis Republic had already been delivered.34 It was as if it had been rushed into print, and he would later realize that the paper’s error-ridden stories reflected that haste. He picked up the paper, went back inside, and turned on a lamp. The story was spread across the front page:

POLICEMAN KILLED, 5 SHOT IN E. ST. LOUIS RIOT

NEGROES, CALLED OUT BY RINGING OF CHURCH BELL, FIRE WHEN POLICE APPEAR

OUTBREAK FOLLOWS BEATING OF WATCHMAN BY BLACK SATURDAY NIGHT

Roy Albertson’s first-person account of the fatal shooting of Coppedge reported that the “pre-arranged signal” for the armed blacks to gather was the ringing of a church bell at an African American Methodist Church at Sixteenth and Boismenue Avenue, deep in the South End and six blocks south of Bond Avenue. There was no mention of a carload of whites, much less two carloads, speeding through black neighborhoods firing out the windows. The story said, “What caused this latest break on the part of the blacks cannot be told now. There was no trouble of a serious nature in the black belt today. The only trouble came early Saturday night, when a railroad watchman was man-handled by a negro, who escaped.”

At the top of the story, in bold type, was a list of five men wounded the night before. Among the wounded, identified as a patrolman, was a man named Gus Masserang. The story said Masserang was shot in the leg, which was true—he was hit many times in the legs, the back, and the neck with shotgun pellets—although the wounds were superficial. However, he was not a policeman but a petty crook who was known to hang out at the Commercial Hotel in downtown East St. Louis.

There were numerous other mistakes in the story, many of them tending to cast a favorable light on the police, who were credited with a whirlwind of activity in the South End when in reality they had stayed close to the station after the shootings of Coppedge and Wodley.35

Although Albertson’s story reported that Coppedge had identified himself and his companions as police officers, the St. Louis Argus—after interviews with African Americans in the South End following the riot—contended that there had been no exchange of words at all before the shooting. The black weekly reported that the policemen in the unmarked police car were “mistaken for rioters” making another attack on the neighborhood, and “the Negroes immediately fired upon” the black Ford, “thinking this was another machine with lawless occupants whose purpose was to repeat the act of the preceding one.”36

On the morning of July 2, a black Model T Ford shot full of holes sat next to the Commercial Hotel. Very few East St. Louisans took notice of that particular machine. Most of the interest focused on another black Model T Ford riddled with bullet holes, all four of its tires flat and shredded, that was parked a block or so away, across the street from the police station.