Developing a Water Supply

Reaching Downward To Tap the Reservoirs Beneath Our Feet

Water is one of the elementary staples of life, and the existence of a dependable supply of drinking water is probably the single most important factor in determining whether a homesite will be livable or not. Virtually all the water we use arrives as rain and collects either on the surface of the ground or beneath it. Most of the privately owned residential water supply in the United States comes from wells. Aboveground sources, such as ponds, lakes, reservoirs, and rivers, supply the remainder, almost always for large-scale users, such as heavy industry and population concentrations in urban and suburban areas.

Digging for water is a centuries-old practice with significant sanitary benefits. Due to natural filtration, well water is relatively pure, whereas water in ponds and streams is highly susceptible to bacterial pollution from human and animal waste. But digging wells manually is hard, sweaty work and at depths greater than 10 to 20 feet can be extremely dangerous as well.

Modern methods of well construction, which rely on boring and driving equipment, water pumps, and drilling machinery, avoid most of the danger but still take time, work, and money. In addition, they remain almost as chancy as ever when it comes to striking water. Old-time dowsers and water witches—people who seem to have a special knack for locating subsurface water—are still consulted, but recourse to common sense, a knowledge of local geology, and a professional well digger's experience are likely to prove better guides. Assistance in finding and developing a well on your property can also be obtained from your state's water resources agency.

Digging a well the old-fashioned way is dangerous work because of the risk of cave-ins; it should never be attempted by an amateur. A typical old-style well-digging operation is shown at right. The well is 3½ ft. in diameter—wide enough for one man to work. A 4-ft. length of 42-in.-diameter steel culvert pipe has been installed at top to keep loose surface soil from crumbling into the well. The pipe extends 6 in. above ground level to prevent supplies and tools from being accidentally knocked in. (Such shoring is considered adequate for a 15- to 20-ft.-deep well in an area with firm subsoil.) The well is dug until water enters faster than it can be bailed out by hand. The bottom part of the finished well is lined with stones. To prevent pollution, the upper part is lined with bricks set in nonporous concrete. The cap is also nonporous concrete.

Old wells were dug with a pick and shovel. When the water table was near the surface and the well shallow, a long counterweighted pole with a bucket at one end sufficed to lift the water up. For deeper wells (they were sometimes dug down 100 ft.), a windlass was used to crank up each bucketful of water. When not in use, such wells should be covered as a safety measure and to keep out dirt and debris.

Where to Find Water

Of the rain that falls on the land areas of the world, the major part collects in lakes and rivers, some evaporates, and the rest, called groundwater, filters slowly into the earth. In many areas groundwater is the most dependable water—often the only water—available.

The top of a groundwater reservoir is known as the water table, a level that moves up and down according to the rate at which water is being taken out and replenished. In some locales the water table is a few feet from the surface—a relief to well drillers; elsewhere, the table is so far down even drilling becomes impractical.

Groundwater is frequently confined within rock formations, where it forms an aquifer, or underground stream. If the aquifer originates from a high elevation, the water may be under enough pressure to bubble up spontaneously to the surface when a drill bit reaches it. This type of natural flow is called an artesian well and does not require a pump. Water tables also break the surface, creating seeps, springs, swamps, and ponds.

Variety of water sources (left) is equaled by the variety of ways water can be tapped. Because of the complex structure of aquifers, wells quite close to each other can nevertheless differ markedly in output.

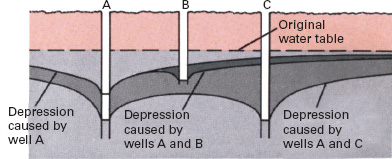

Wells draw the water table down in their vicinity, sometimes causing neighboring wells to dry up. In the example shown below, well A was dug first, creating a dry cone-shaped volume around it. Next came well B, which produced water until well C was put in.

Small-Diameter Well Construction

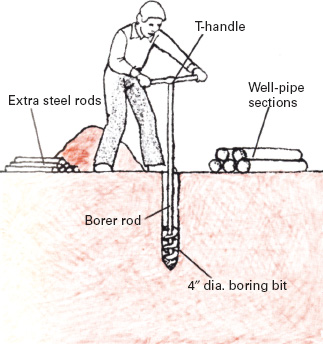

Bored well can be put in with inexpensive hand tools. First a 1-ft.-deep hole is driven with a pick or crowbar, then the borer introduced. As the borer penetrates, segments are added to its rod to accommodate increased depth. Periodically, the borer must be lifted to empty the hole of loosened cuttings. Boring is impractical for wells deeper than 50 ft. Moreover, if a large stone or a rock formation is met, the operator has to abandon the hole and start again elsewhere. After water is encountered, the well pipe and water intake are installed.

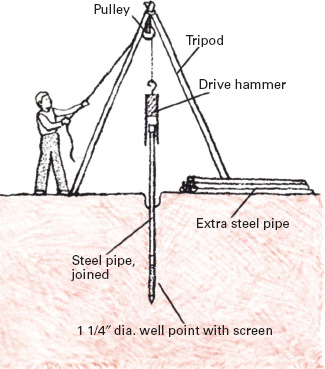

Driven well is put in by hammering a pipe directly into the earth. The point of the pipe is screened to keep dirt out, since it will serve later as a water intake. The pipe is hammered in by repeatedly dropping a heavy weight on it. Well depths of up to 150 ft. can be achieved with equipment like that illustrated. To check for the presence of water, lower a weighted string down the pipe, then raise the string and examine the end to see if it is wet. Once water is detected, drive the pipe down another 20 to 30 ft. to guarantee water supply.

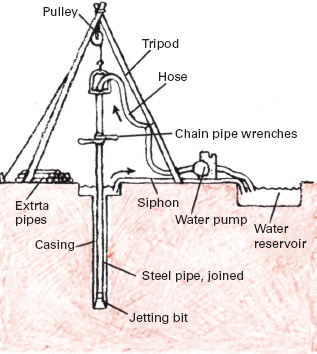

Water-jetted well can be put in fairly rapidly with a pump that forces water down a pipe. The water pressure jars the soil loose and forces it up the well hole to the surface. As the well deepens, the pipe should be rotated periodically to help keep it vertical. The mud in the upward flowing water helps to line the well wall and prevent crumbling. A casing, installed as the well is being jetted, will further reinforce the wall. If no rock formation is encountered along the way, a strong pump can jet a 1-ft.-diameter well to a depth of 300 ft.

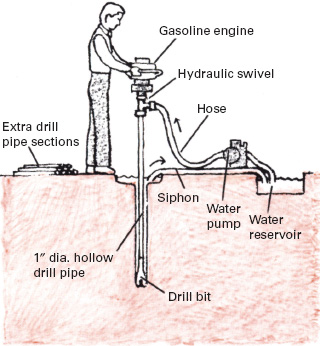

Drilled well can penetrate thousands of feet below the surface; the depth is limited only by the power of the drilling engine and the quality of drill bit used. For very hard rock, diamond-tipped bits are required. A hand-held, 3-horse-power drilling unit like the one shown can reach a depth of about 200 ft. A water pump is used to wash soil and rock cuttings to the surface and to cool and lubricate the bit. After the hole is drilled, the hole is reamed to a diameter of 3 in., and the well pipe and screen (or submersible pump) are installed.

Aboveground Storage In Pond or Cistern

Of the various types of surface water the most valuable for a home water supply is a spring. Springs can be thought of as naturally occurring artesian wells, the water being pushed to the surface by gravity. A mere trickle can support the water needs of a home if it is collected in a cistern or holding tank. A spring's flow can be measured by timing how long the spring takes to fill a 5-gallon container. For example, if the container takes 30 minutes to fill, the spring will provide 10 gallons an hour, or 240 gallons of water a day—enough to support a small homestead. Remember, however, that springs can run dry at certain times of the year.

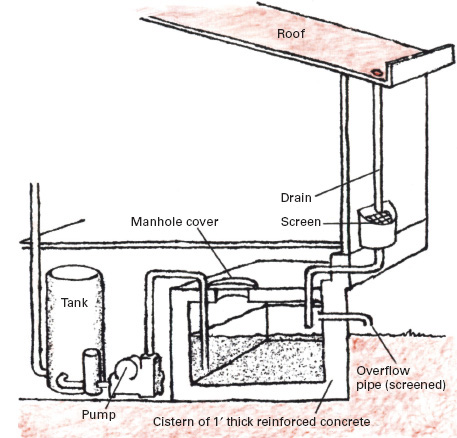

In some areas the most practical way to obtain drinking water is to channel rain falling on a roof into gutters that lead into a cistern. In a region of moderate rainfall (30 inches per year), a roof with a surface area of 1,000 square feet will collect an average of 50 gallons of water per day, enough for a two-person household with modest water needs. Since rainfall varies over the year, the cistern must hold enough water to cover expected dry periods. For example, a 50-gallon-per-day requirement could be supported for 30 days by a cistern that is about 6 feet on each side and 5 ½ feet deep. Cisterns up to five times this size are practicable.

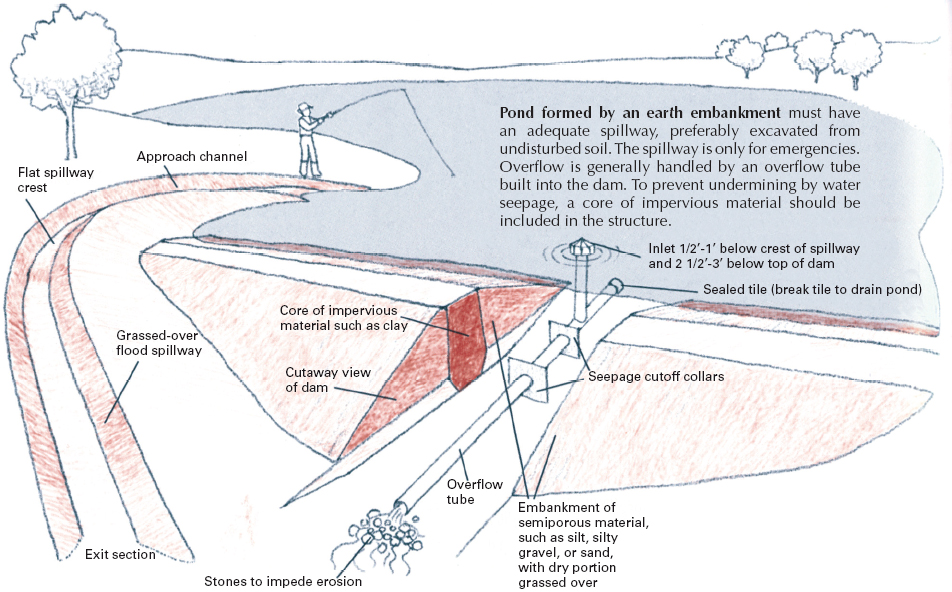

For large-scale water storage a pond is usually the best alternative. Ponds are excellent for such major uses as irrigation, livestock maintenance, and fish farming. In addition, they attract and support wildlife and provide water for fire protection if located within 100 yards or so of the structure to be protected. A pond can be a simple excavated hole if the water table at the site is close to the surface, or an earth embankment can be built to collect runoff. Unless the pond is also intended for power generation (see Waterpower, p.98), you should not attempt to impound a running brook. (There are legal restrictions that govern the development and use of waterways, and, in addition, a large and expensive spillway may have to be constructed.)

The probability is high that water from ponds, brooks, and similar aboveground sources will not be healthy enough to drink, particularly if livestock have direct access to the water source or if the source is located in areas suffering from pollution, such as mining regions. If necessary, water can be purified with ceramic filters or by chlorination. In emergencies the water can be boiled.

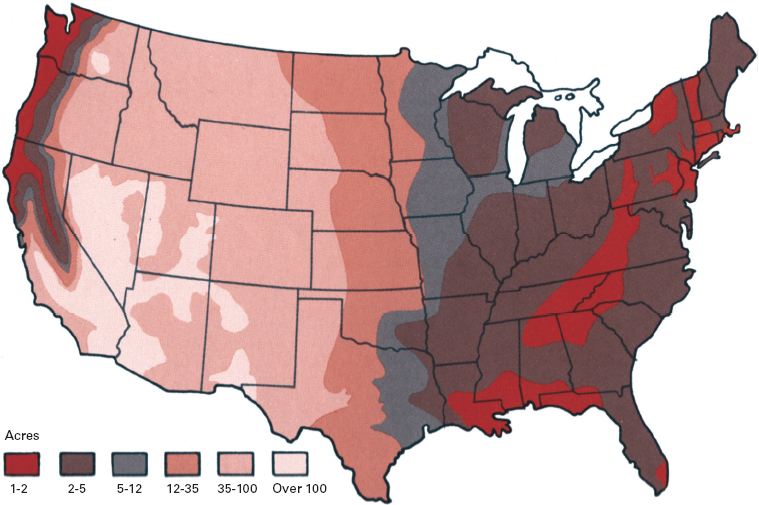

Use map to estimate acreage you will need to maintain a pond of a chosen size in your part of the country. The map is derived from annual rainfall data and specifies how many acres of rain-runoff area are required for each acre-foot of pond water. For example, to create a ¼-acre, 4-ft.-deep pond (1 acre-ft.) in eastern Nebraska will require 12 to 35 acres of runoff area.

Ways to Collect and Store Rainwater and Spring Water

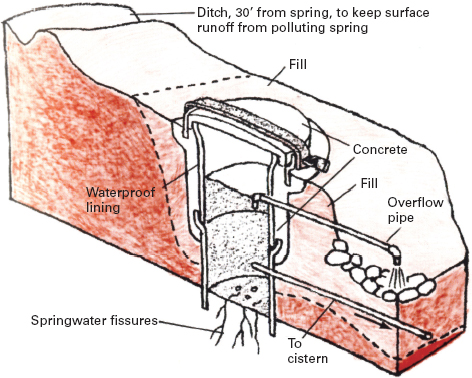

Spring water collection structure, formed primarily of concrete, helps stabilize water flow and protects water from surface contamination. Take care when excavating to avoid disturbing the fissures; otherwise the flow can be deflected.

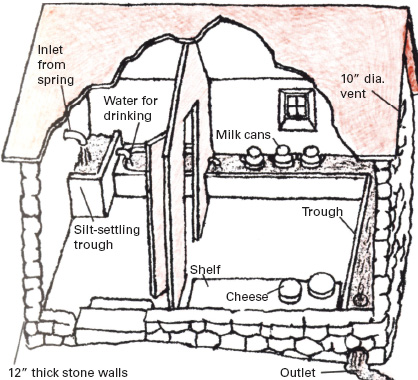

An old-style springhouse

Springhouse of the type built last century put a spring to work to keep food cool. Such perishables as milk and butter were placed in containers, and the containers were set in a trough through which cool spring water flowed, keeping the food at refrigeratorlike levels even in summertime.

Typical cistern can hold 180 cu. ft. of water. Since water weighs 62.4 lb. per cubic foot, the cistern and its foundation must be massive enough to hold 5 to 6 tons of water. The entire system should be screened and sealed against insects.

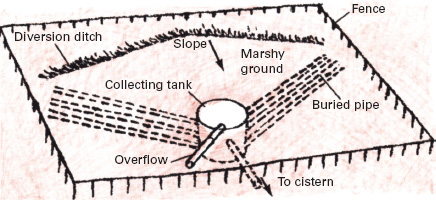

Marshy area can be tapped for water with a system of perforated or open-joint pipes draining into a tank. Pipes are buried in packed gravel faced by a plastic barrier on the downslope side to help concentrate water near them.

Springhouse is made of stone and built into the hillside to keep the interior cool in all seasons.

Sources and resources

Books and pamphlets

Campbell, Stu. Home Water Supply: How to Find, Filter, Store, and Conserve It. Charlotte, Vt.: Garden Way Publishing, 1983.

Manual of Individual Water Supply Systems. Washington, D.C.: Environmental Protection Agency, 1987.

Matson, Tim. Earth Ponds: The Country Pond Maker's Guide. Woodstock, Vt.: Countryman Press, 1991.

Wagner, Edmund G., and J.N. Lanoix. Water Supply for Rural Areas and Small Communities. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization, 1959.