Saunas and Hot Tubs

Using Warmth and Ritual For Total Relaxation

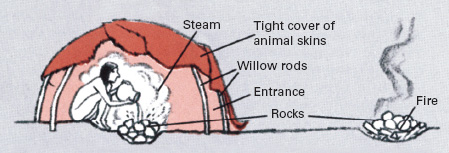

The beneficial effects of a warm bath have been recognized for thousands of years. The sauna, a hot-air bath followed by a quick cool-down, originated before the birth of Christ. In pre-Columbian North America, so-called sweat baths, remarkably similar in detail to the sauna, were a common custom among Plains Indians, and the Japanese have long practiced communal hot-water bathing. Recently, Americans have begun to take an interest in communal heat baths, primarily because of the sense of shared contentment they provide. The interest has focused on the traditional Finnish sauna, along with a new development: the hot tub.

Saunas today are much like those used in Finland for centuries. The hot tub is an American idea, conceived a few years ago by Californians who converted discarded wine vats into bathing units. Both saunas and hot tubs should be used with care, however. Hot tubs should be kept below 103°F and saunas below 170°F. Pregnant women and persons with heart conditions should avoid them altogether.

A-frame sauna is located next to a serene lake with a stunning view. Taking a sauna is not so much a way to get clean as it is a means of achieving profound emotional relaxation. The ritual of the sauna begins with a “perspiration bath” in hot dry air. Next comes a brief steaming, followed by a beating with leafy birch twigs. Then the bathers wash, plunge into the snow or into a cold lake, and dry off. The final phase is a period of rest and relaxation, preferably in the open air.

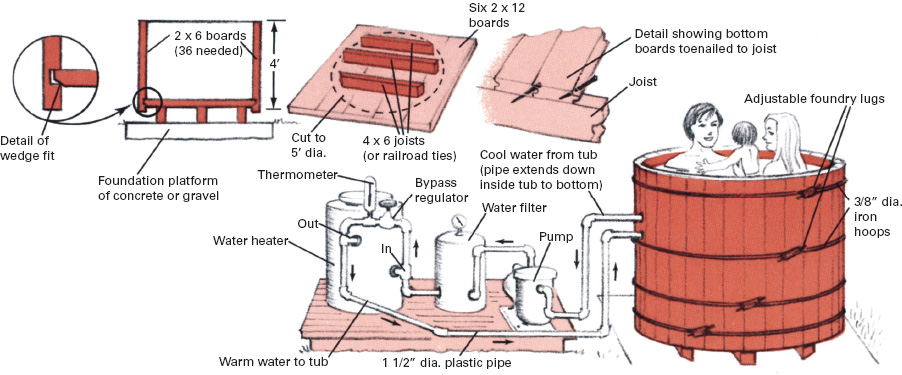

Make Your Own Hot Tub

Hot-tub design shown here can be tailored to your own needs. Nail bottom boards to joists before sawing out circle. Then add staves, slip on hoops, and tighten lugs.

The wine vat is the prototype of all true hot tubs. A tub the size shown here holds about 500 gallons, or 2 tons, of water. To sustain such a load requires strong wood and a stable foundation. For the benefit of bathers, the wood should not be resinous or splintery. Spruce or cedar are good choices, but redwood is the best.

The bottom of the tub should be as watertight as possible. Ask the lumberyard to mill either tongue-and-groove or shiplap joints on the bottom boards; then coat the joints with roofing mastic along the lower edges and nail the boards to the joists. Use 8d galvanized finishing nails. Drive them at an angle, countersink them, and top them with mastic. To make the tub sides, bevel both edges of each stave between three and five degrees off right angle and notch them near their lower ends to fit the bottom boards. Coat the outer halves of the edges and the bottom of each notch with mastic, then tap the staves in place one by one around the tub. The last stave will have to be trimmed to fit. Put the hoops loosely in place, then tighten them, starting with the lowest hoop (which is placed where the staves join the bottom).

The capacity of most home hot-water systems is too small to fill a hot tub. For continuous high temperatures and clear water while bathing, use a heater, filter, and pump, rigged as shown. These items are best purchased as a group from a supplier dealing in hot-tub equipment.

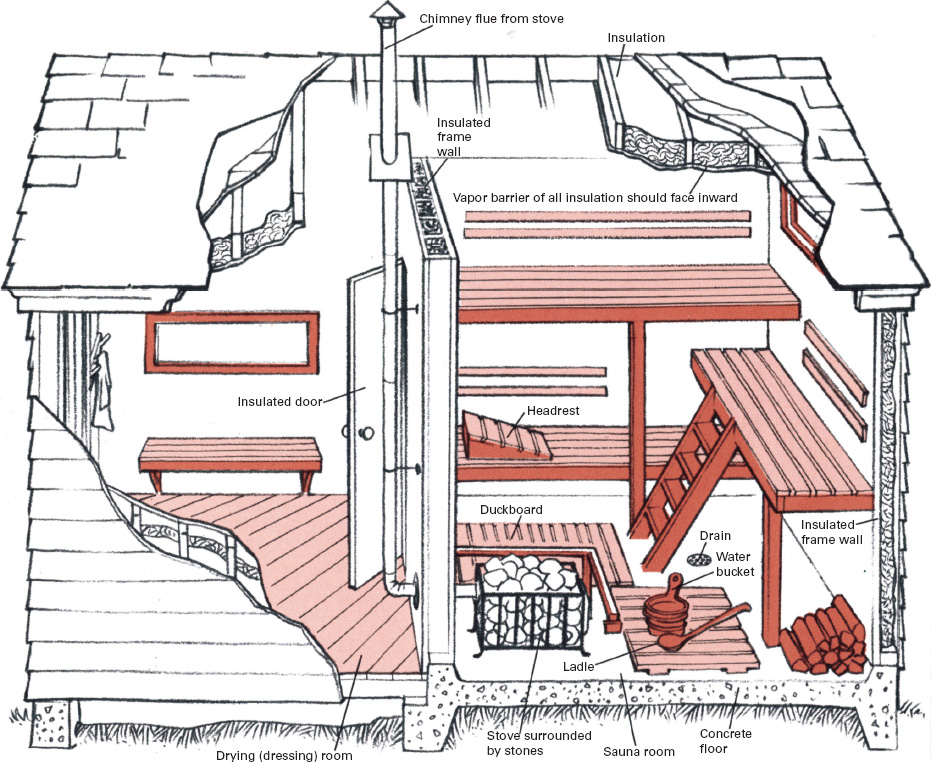

Building a Sauna

To conserve heat, a sauna should be as compact as possible, especially the bathing area. The ceiling should be low, the windows small and double paned, and the doorway low and narrow. For a quick exit in case of an emergency, have the door open outward.

Saunas are invariably made of wood. Frame construction is the most economical, but log construction is more traditional and deemed superior because of the ability of logs to retain and reradiate heat. (For log construction techniques, particularly the chinkless style often used for saunas, see Building a Log Cabin, pp.26–35.) For a frame sauna, start with a poured cement slab foundation, or use concrete piers and bolt the sills (large foundation lumber) onto them. Beveled siding, tongue-and-groove boarding, or plywood can be used on the exterior, with wood shingles on the roof. The wood should not be painted or varnished; instead, impregnate exterior woodwork with preservative, or use durable lumber, such as redwood. Install a minimum of 4 inches of foil-faced insulation in the roof and walls. The foil should face the sauna's interior. Since exposed metal can burn the skin, all implements and handles should be wooden, and all nails should be countersunk. Round off bench edges with sandpaper, and use duckboards-movable slatted flooring—to protect feet from a cool floor.

A wood-burning stove is traditional, but an oil, coal, gas, or electric heater can be used instead. (To install a wood stove, see Heating With Wood, p.86.) The heating stones around the stove should be dense enough to store a large amount of heat and should not crack when heated; cobblestone-sized pieces of granite or lumps of peridotite, a dark igneous rock, are often used.

The high air temperatures in a sauna are bearable because the air is fairly dry and because bathers can take the heat in stages, first on the bottom benches where temperatures are lower, then on the higher benches. For breathing comfort, water should be ladled onto the stones now and then to add a bit of moisture to the air. After 15 or 20 minutes the bather cools off in an icy lake, new fallen snow, or a cold shower.

Interior walls of the sauna should have a natural timber surface, and neither oil, varnish, paint, nor wax should be applied to them. The wood selected for the benches and interior paneling should be durable and should show high resistance to splitting and splintering in order to withstand the wide swings in temperature to which it will be subjected. Eastern white pine or sugar pine are often used for the interior paneling, since both have a pleasant resinous aroma that adds to the sauna experience. For the benches, however, a nonresinous wood should be selected because contact with the resin is irritating to the skin; white cedar or western red cedar are good choices.

Saunas often have auxiliary rooms in addition to the main sauna room; the sauna shown here has a dressing room attached. The extra room has supplementary uses, such as providing a place to hang up the wash or acting as a guest room for overnight visitors. Benches in the sauna can be any size or shape imagination suggests but should always be built to provide at least two distinct bathing levels, and preferably three, on which bathers can recline full length. Bench seats should be slatted to improve heat circulation and designed to permit access to the floor beneath them so that cleaning will be easy. If the benches are movable, cleaning becomes simpler yet.

Sources and resources

Books and pamphlets

Cowan, Tom, and Maguire, Jack. Spas and Hot Tubs, Saunas and Home Gyms. Saddle River, N.J.: Creative Homeowner, 1988.

Herva, M. Let's Have a Sauna. Washington, D.C.: Sauna Society of America, 1978.

Nelson, Wendell. Of Stones, Steam and the Earth: The Pleasures and Meanings of a Sauna. New Brighton, Minn.: Finnish America, 1993.

Sherwood, Gerald, and Stroh, Robert C., eds. Wood Frame House Construction: A Do-It-Yourself Guide. New York: Sterling Publishing, 1992.