Sanitation

Disposing of Waste Without Wasting Water

Modern sanitation methods, such as flush toilets, septic tanks, leach fields, and sewerage treatment plants, have come to be taken for granted. Not only is their vital role in preventing the proliferation of contagious bacteria all but forgotten, but their imperfections are often ignored, particularly the enormous amount of water they consume. In addition, the sheer volume of waste that now pours into our lakes and rivers is beginning to overtax the ecosystem, destroying wildlife and polluting the waters.

In recent years attention has begun to focus on new kinds of waste disposal devices that greatly reduce water consumption and at the same time convert the waste into nonpolluting material. Some new types of toilets have cut water usage to 2 quarts per flush, others go further, doing away with the flush method entirely. Among the latter are toilets that incinerate the refuse, toilets that partly decompose the refuse through anaerobic (oxygenless) digestion—outhouses are a somewhat primitive example—and toilets that turn the refuse into high-quality compost via aerobic decomposition. Some of the newest approaches are finicky to operate, and others are costly to install; but most hold promise for saving water and energy while reducing pollution.

Sources and resources

Books and pamphlets

Hartigan, Gerry. Country Plumbing: Living With a Septic System. Putney, Vt.: Alan C. Hood Publishing, 1986.

Kruger, Anna. H Is for EcoHome: An A to Z Guide to a Safer, Toxin-Free Household. New York: Avon, 1992.

Wagner, E.G., and J.N. Lanoix. Excreta Disposal for Rural Areas and Small Communities. Geneva: World Health Organization, 1958.

Whitehead, Bert. Don't Waste Your Wastes—Compost ‘Em: The Homeowner's Guide to Recycling Yard Wastes. Sunnyvale, Tex.: Sunnyvale Press, 1991.

Wise, A.F., and Swaffield, J.A. Water, Sanitary and Waste Services for Buildings. New York: Halsted Press, 1995.

Primitive but functional outhouse is still standing from the early 1900s. Familiar crescent moon ventilating hole once meant “For ladies only.”

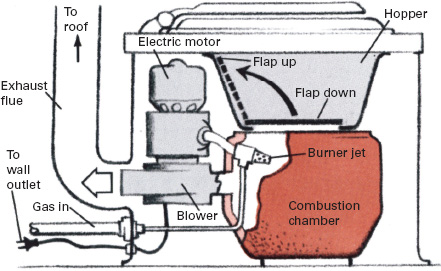

Incinerating Toilets

Refuse is converted to sterile, odorless ash in incinerating toilet. When top lid of seat is lifted, flap beneath the seat opens and a cycle timer is set. When lid is closed again, the flap drops down and refuse burns for about 15 min., after which unit is cooled by blower. Burner is fueled by natural or LP (liquid propane) gas. Hopper should be washed once a week and ash removed from combustion chamber with a shovel or vacuum cleaner. Toilet is effective but relatively costly to run and cannot take overloading—as might happen if the owner were to host a large party.

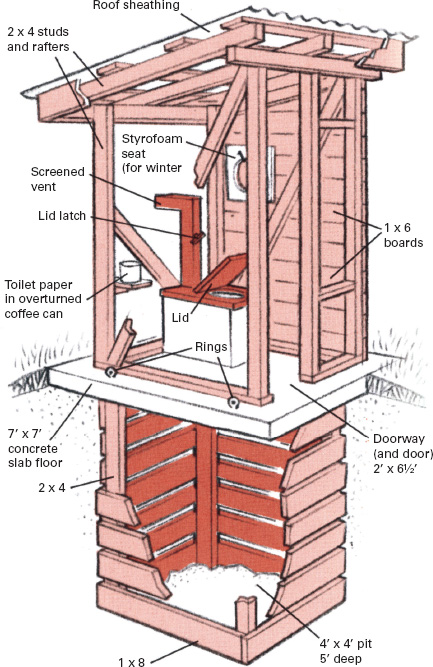

Pit Privies

Pit privy, or outhouse, must be located where it will not pollute the water supply. Place it downhill from any spring or well and be sure that the water table, even at its highest level, is several feet below the bottom of the privy's pit. A pit with the dimensions shown will last about five years if used continuously by a family of five. Once the pit fills up, it must be covered and the privy moved to a new site. Though safe and sanitary if properly constructed, pit privies tend to be smelly. They are also uncomfortable to use, especially in winter.

Privy is built on precast concrete slab to stop rodents and divert rain from pit. Rings cast in slab permit entire structure to be hauled by tractor to a new site when pit becomes full.

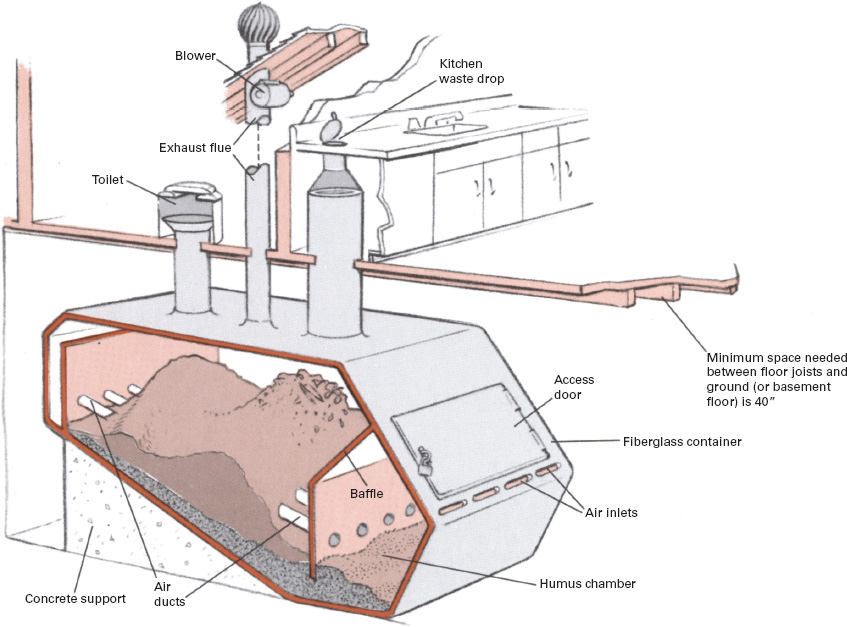

Composting Toilets

Large size of container in this composting toilet means that system likely requires almost no attention in normal operation. Mass of waste matter slides slowly down incline, decomposing as it moves. By the time it reaches lower end of container, it will have turned into high-grade fertilizer. System of perforated pipes and baffles helps supply oxygen to aerobic bacteria that digest the refuse. To keep bacteria at peak efficiency, the wastes should include such vegetable refuse as kitchen scraps and lawn clippings. The chimney exhausts occasional odors and supports air flow through the container.

Unlike outhouses, composting toilets are just about odorless. Their chief requirement is a steady supply of air to maintain the aerobic (oxygen-loving) bacteria that feed on the refuse inside the fiberglass composting container. These bacteria function best between 90°F and 140°F—temperatures considerably higher than normal room temperature. A properly designed container can lock in the warmth generated by the bacteria themselves, helping to maintain the ideal temperatures.

In principle, a composting toilet does not require energy to operate. In practice, however, this is likely to hold true only in warm climates. In colder areas, during the winter, the composter will generally draw warm air from the house interior, venting it to the outdoors. In extremely cold regions, such as Maine, northern Minnesota, and Alaska, the composter may even require an auxiliary heater to maintain the proper composting temperature. Occasionally, a blower must be added to the exhaust flue to prevent odors from seeping into the house via the toilet seat or kitchen waste access port.

A composting toilet must usually be supplemented with a small standard septic tank and leach field to handle greywater (water from the bathtub, washer, or sink). Generally, a composting system is most economical where water is in short supply or where soil and topography combine to limit the effectiveness of more conventional waste disposal systems.

To offset the rather high cost of commercial models, some homeowners have tried building their own composting containers out of concrete block or other material. The job is difficult and can lead to problems, such as compost that does not slide properly and solidifies in the tank. Should that happen, the container must be broken open and the compost chipped out.

Other Toilets

A number of new waste-disposal devices have recently appeared on the market. Most are for special needs, such as a vacation home or in arid climates.

Chemical toilets employ a lye solution to destroy bacteria; the waste must be emptied and disposed of periodically. They are safe but have a tendency to give off an offensive odor.

Freezer toilets are odor free but require an energy-consuming compressor to freeze the waste; like chemical toilets, they must be emptied at intervals.

Vacuum toilets are fairly expensive. They work like waterless flush toilets, using special plumbing and a pump that sucks the waste into a collecting chamber.

Nonaqueous flushing systems imitate conventional toilets, but instead of water they recycle treated oil. Like vacuum toilets, these systems are expensive.

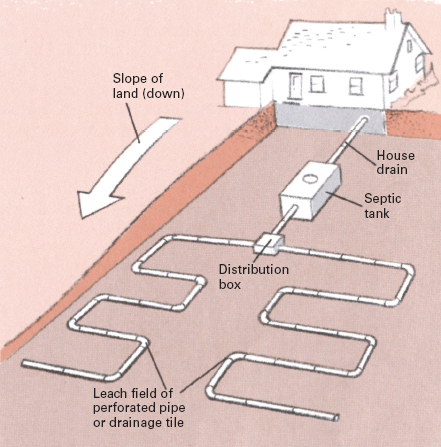

Greywater disposal

Typical septic system has a 200-cu.-ft. holding tank and a 120-ft. leach field. The field consists of pipe made of clay tile or perforated fiber buried 1½ to 3 ft. deep. The tank can be concrete, fiberglass, or asphalt-lined steel, with an access port to pump out accumulated sludge. Dimensions of system can be reduced one-third if waterless toilets are used. Excavation for system can be by hand, but the job is more easily handled with mechanized equipment, such as a backhoe.