Fireplace Construction and Design

The Welcoming Hearth: Rumford Rediscovered

The theory of fireplace design is almost entirely the work of a single man-Benjamin Thompson, better known as Count Rumford, an American Tory of the colonial period who eventually fled to England. Rumford's findings, particularly his discovery that a wide, shallow firebox radiated the maximum amount of heat into a room, revolutionized fireplace design in the early 1800s. The introduction of cast-iron stoves, however, followed later by an almost universal conversion to oil, gas, or coal central heating, changed the role of the fireplace from that of a vital home-heating device to a mere status symbol; along the way many of Rumford's precepts were forgotten or ignored: in an age of limitless energy fireplace efficiency no longer seemed important.

Nowadays, Rumford's ideas are enjoying a renaissance. Although the Uniform Building Code restricts total adherence to Rumford's principles, it is still possible to construct a fireplace that comes close to the energy-efficient ideal. With a Rumford-style fireplace the fellowship and security that a blazing open hearth inspires can be enjoyed at a minimum cost and with a maximum of home-heating warmth.

How a Fireplace Works

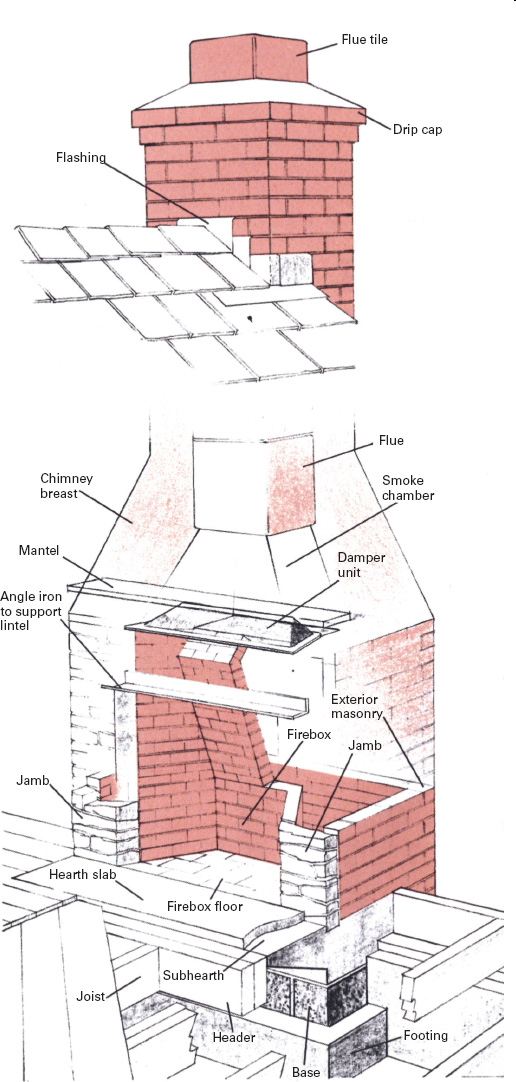

Fireplaces are basically hollow towers constructed out of strong, long-lasting, heat-resistant materials, such as stone, brick, adobe, or metal. They can be designed in a myriad of shapes and sizes; but no matter what they look like on the outside, all fireplaces are virtually alike inside, consisting of four basic units. These are the base, firebox, smoke chamber, and chimney. The hollow core of the chimney is called the flue.

The base is simply the platform upon which the upper sections of the fireplace rest. It should be solid and massive in order to support the weight of the heavy masonry above it. The firebox, built atop the base, is where the fire is set. Most fireboxes are lined with a special type of brick, called firebrick, which will withstand high temperatures. The design of the firebox should allow heat generated by the fire to be radiated outward into the room, while at the same time preventing heat from escaping up the chimney in the form of hot gases. The funnel-shaped smoke chamber is erected directly above the firebox. It serves as a transition unit, channeling the smoke from the fire below into the flue above. The final unit, the chimney, carries the smoke and hot gases away and passes them into the atmosphere.

In order to work efficiently, the firebox, smoke chamber, and chimney should be built in correct proportion to each other. The smoke chamber should have a smooth interior surface and should slope inward from its base toward the chimney opening at an angle no greater than 30 degrees from vertical. The area of the chimney opening itself should be about 10 percent of the area of the firebox opening. In addition, the size of the fireplace must fit the proportions of the room. Air drawn by the fire has to be replaced. In a small room the strong draft of a large fireplace will suck warm air out of the room and send it up the chimney. To replace this warm air, additional air will be drawn into the room, most likely from outdoors through cracks around the windows and doors. Not only is this wasteful but the room may actually be cooler than it would have been with a smaller fireplace that drew less air.

Sources and resources

Books and pamphlets

Brann, Donald R. How to Install a Fireplace. Briarcliff Manor, N.Y.: EasiBild, 1978.

Edwards, Alexandra. Fireplaces. San Francisco: Chronicle Books, 1992.

Manroe, Candace O. For Your Home: Fireplaces and Hearths. New York: Little, Brown & Co., 1994.

Orton, Vrest. The Forgotten Art of Building a Good Fireplace. Dublin, N.H.: Yankee Books, 1969.

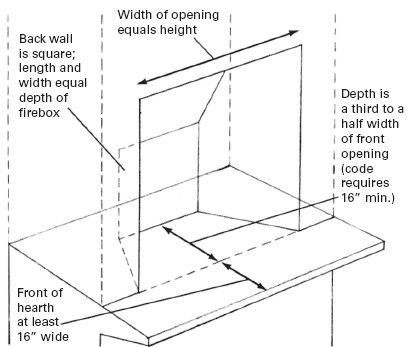

Traditional-style fireplace (right) has the shallow heat-radiating firebox characteristic of the Rumford design. This feature is the main reason for its excellent heating ability. The firebox and other elements of the Rumford design, including a wide smoke chamber, can be incorporated into almost any style of fireplace from modern to traditional. In general, the width of the front opening should be restricted to no more than 42 in.; anything wider will result in lower efficiency for most rooms.

Planning a Rumford Fireplace

Determine the size and overall shape of your fireplace by making drawings and scale models of various design possibilities, then taking the time to analyze each. The location of a fireplace should not interfere with household traffic, and its exterior should harmonize with the surroundings. It is also important to realize that many fireplace components—bricks, flue tiles, dampers—are manufactured in standard sizes and that your designs must take these fixed dimensions into consideration. For example, the Rumford-style fireplace whose construction is shown here uses a standard 10-inch-wide cast-iron damper and standard-sized terra-cotta flue tiles; neither was available in Rumford's day.

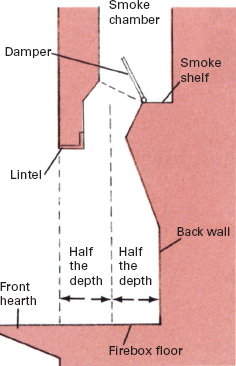

Rumford firebox (above) is designed for maximum radiation. Front opening is square. Ideal firebox depth is one-third the width of front opening but at least 16 in. deep in order to satisfy Uniform Building Code requirements.

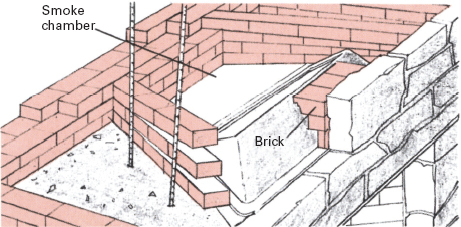

Smoke chamber (right) should begin at least 8 in. above lower edge of lintel. Damper is centered over firebox floor so that smoke can travel vertically into smoke chamber. The chamber itself tapers gradually to the same dimensions as the chimney flue opening.

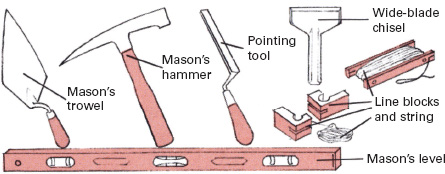

Tools and materials

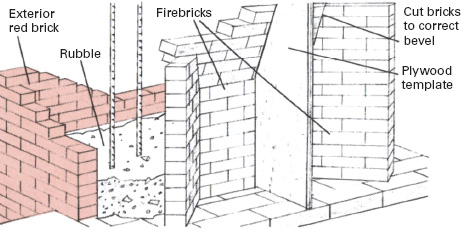

Tools for fireplace building are the same as those used in other stone and concrete work. Some of the more specialized tools are shown below. Among materials you will need are cement, sand, and concrete block for the footing, base, and hearth; firebrick for the firebox; ordinary red brick for the smoke chamber, exterior, and chimney; and terra-cotta flue tile for the chimney interior. Some special mortar and concrete mixes are also necessary (see chart at right).

Building a fireplace requires only a few basic masonry tools.

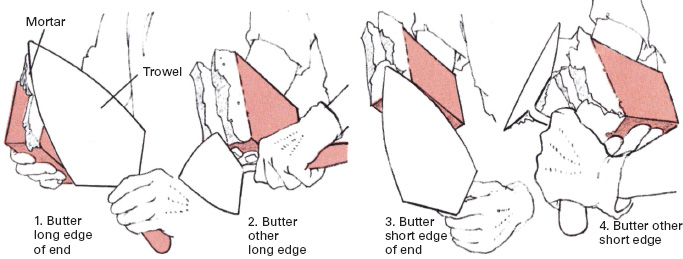

The bricklayer's art

Practice applying mortar and raising walls before actually starting to build. Sequence shows proper way to “butter” the end of a brick with mortar for firm bond. Dip bricks in water before buttering them. Remember that mortar is caustic and abrasive. It should not be worked by hand or come in contact with bare skin.

Raising a brick structure

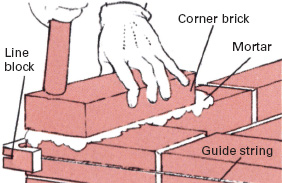

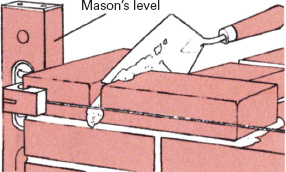

1. Lay corner bricks first. Set each one atop mortar base so that outside corner touches plumb line. Hold brick in place with one hand; level it by tapping the edges with trowel handle.

2. Set second brick in place on mortar base 3/8 in. from corner brick. Align by tapping with trowel handle. Carefully fill gap between bricks with mortar, taking care not to disturb corner bricks.

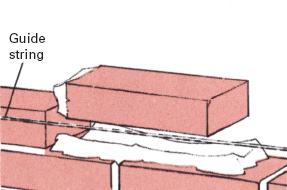

3. Lay succeeding bricks in a similar fashion, but butter one end of each before installing it. Work from corners toward the center; keep bricks in line with guide string held by line blocks.

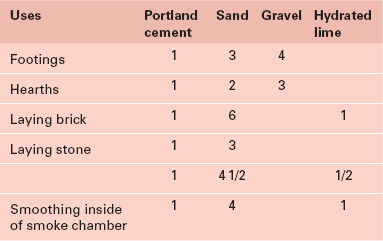

Mixing guide for concrete and mortar

Chart shows correct proportions for mixing both concrete and mortar to suit different applications. Two blends are shown for laying stone; the second one is a stiffer mix than the first, but both are of equal strength. For all formulas mix the dry ingredients first, then add water until smooth.

From Footing to Flue: Building a Fireplace

Exact fireplace dimensions are impossible to specify, since each must be designed for the room it is to heat. Typical hearth openings, however, are 32 to 38 inches square, and from these initial opening dimensions the rest of the fireplace can be designed proportionately according to the rules and considerations given on pages 62 and 63. Strict adherence to Rumford's principles is not necessary in order to derive most of the increased heating ability of a Rumford-style fireplace. Wherever possible, choose dimensions that will allow you to use bricks and concrete blocks without extra shaping.

Use high-temperature mortar for the firebox sides and back. Make the mortar by mixing 1 pound of fire-clay per 6 ounces of water, or buy premixed air-setting refractory cement at a boiler or kiln repair shop.

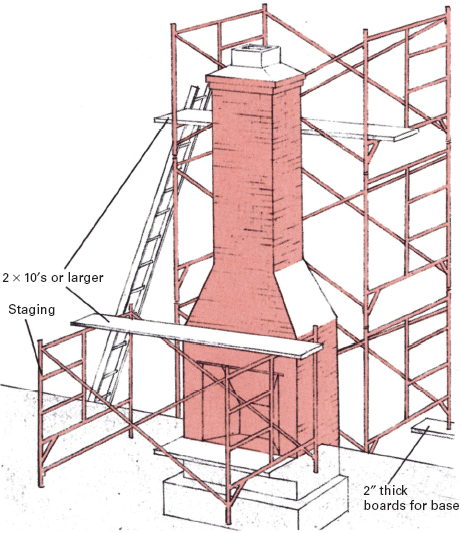

Rent modular staging from a construction supply center. When putting it up, make sure it is level and plumb. Support the legs on wide boards 2 in. thick. Check often to detect sagging.

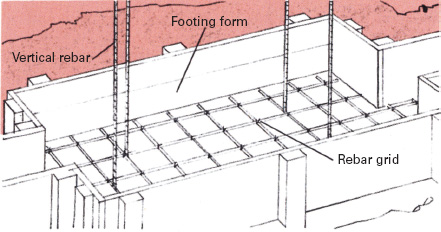

1. Install rebar (steel reinforcing bar) grid and, if code requires, vertical rebar as well. Make grid by wiring lengths of ¾-in. rebar together to form 8-in. squares. The concrete footing should be 12 in. thick and extend 8 in. beyond dimensions of chimney breast on all sides. Footing must lie below frost line.

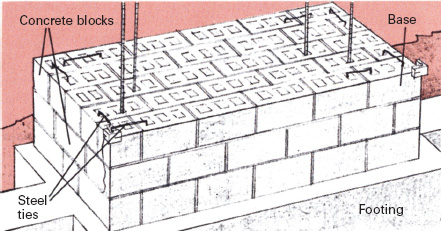

2. Distance between top of footing and bottom of subhearth (Step 3) should be divisible by thickness of concrete blocks used for base plus their mortar joints. Construct base atop footing. Drop plumb lines; use line blocks to keep courses level. Install ¼-in. horizontal steel ties every 18 in. between courses.

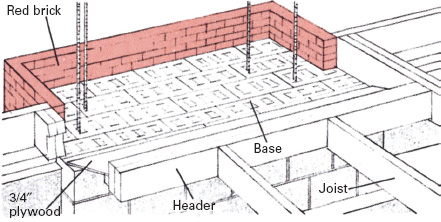

3. Subhearth must extend at least 16 in. in front of firebox. Prepare for its pouring by laying two courses of red brick around exterior of base. Joists and headers serve as remainder of form with ¾-in. plywood as bottom. Concrete blocks that enclose rebars should be packed with concrete; fill others with rubble.

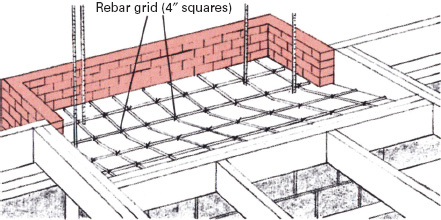

4. Allow 24 hours for mortar on double layer of bricks to set. Lay down grid of ½-in. rebar, elevated with brick scraps so that mesh will be in center of slab. Pour concrete 4 in. thick at thinnest (interior) edge, then level and smooth. Upper surface of subhearth should come no higher than level of subfloor.

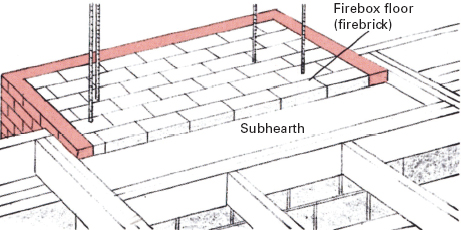

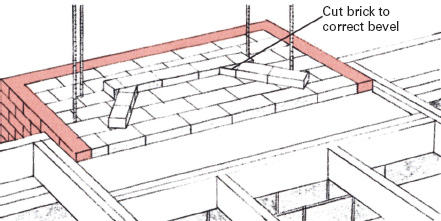

5. Form firebox floor by laying dampened firebricks tightly together on bed of mortar spread on rear of subhearth. Do not mortar joints between bricks. Ideally, top surface of firebrick should be flush with finished house floor. Front hearth slab, installed after all work is done, can rise 1 in. higher to trap ashes.

6. Mark firebox dimensions on firebox floor and begin laying fire-brick for firebox sides and back. Cut bricks to size with mason's hammer or use a power saw with a masonry blade. Lay one course at a time, working from the back toward each side. Mortar joints must be less than ¼ in. thick.

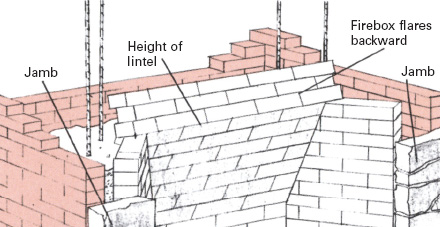

7. Use plywood template cut to angle of firebox back in order to lay slanted bricks. Hold template in place against each brick as it is laid: mortar must harden somewhat before template can be removed. Continue to build up exterior brickwork, filling in around and behind firebox with rubble.

8. To accommodate standard 10-in.-wide damper, flare top of firebox backward, beginning above lintel height, so that basic Rumford design is not affected. Next, build up jambs on each side (stone can be used instead of brick). There must be at least 8 in. between the firebox sides and the house walls.

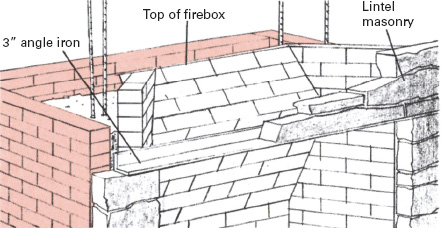

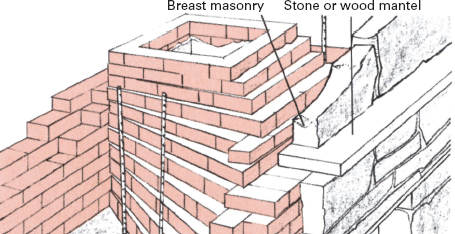

9. Lay up jambs so they are level at lintel height, then install 3-in. angle iron to support lintel masonry. Continue to lay material above the lintel until it is on the same level as the top of the firebox. Smooth the interior surface of the lintel masonry with a coating of mortar.

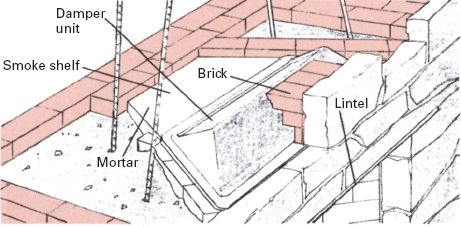

10. Install damper unit on top of the firebox and lintel masonry. Position it so that smoke can rise vertically into chimney when damper is open. Build up the exterior masonry and rubble until both are even with top of firebox, then smooth the area behind firebox with mortar to form smoke shelf.

11. Build smoke chamber of ordinary brick. Set the courses stepwise so that each extends about 1 in. beyond the course below and tapers to the size and shape of the chimney flue. Be sure to allow clearance for damper to function without binding. Smoke chamber should slope inward at no more than 30° angle.

12. Smooth the interior of smoke chamber with mortar as you proceed. When front slope provides enough space, install mantel atop lintel masonry, and construct chimney breast behind mantel. Breast masonry should be same material as jambs and lintel if exposed or ordinary brick if hidden behind wall.

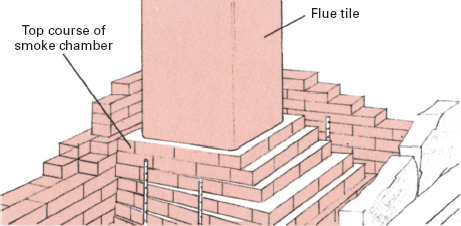

13. Spread mortar on top course of smoke chamber and install flue tile. Check that tile sides are plumb, shimming them with brick scraps if necessary. Scrape away any mortar inside flue. Lay up courses of exterior brick, setting in the sides until 6-in. gap surrounds flue. Fill gap with rubble.

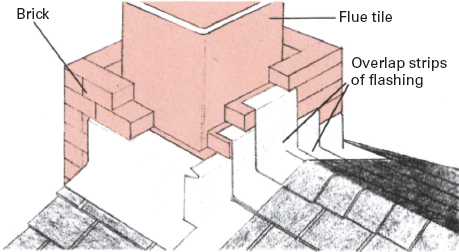

14. Continue building chimney by adding additional flue tiles and bringing up exterior masonry and rubble fill. Where chimney penetrates roof, install metal flashing between courses, overlapping each piece 4 in. Copper is the best material for flashing, although galvanized steel or aluminum may be used.

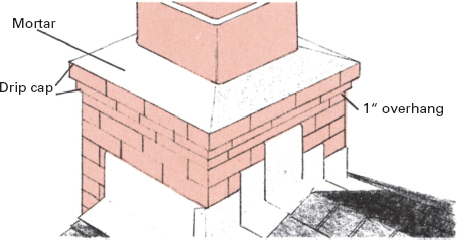

15. Finish chimney with drip cap made by overlapping two courses of brick so that each overhangs the one below by 1 in. Spread mortar on top; smooth and bevel surfaces so they shed water. For protection from cross drafts chimney height should be 3 ft. higher than any other point within a 10-ft. radius.