CHAPTER 4

For decades, “fats” have been considered a four-letter word. But nothing can be farther from the truth. In fact, fats are one of the most beneficial substances in the diet and are often the missing ingredients in developing and maintaining optimal health and fitness. Fats play a key role in controlling inflammation and pain, hormone balance, and energy production.

An ongoing, well-financed misinformation campaign against fat has misled the public into creating an epidemic of fat phobia—all while the obesity rates have increased. Manufacturers took natural fats out of foods and replaced them with refined carbohydrates, including sugar. Billions of dollars are spent promoting and selling the low-fat and fat-free message. It’s a message that is unhealthy and false.

Even worse is the manufacturing and marketing of low- or nonfat-packaged foods or meals. These products are highly processed and often require chemical additives to remove the natural fats and oils. One problem is that when fats are removed from a food, the taste deteriorates. Consider low-fat yogurt. Manufacturers reduce the tasty fat component but must add something back to make the product more palatable. This usually is sugar. No-fat products are often more sweetened. Many low- and nonfat yogurts have 20 to 30 grams of sugar added!

Low- and nonfat foods with all this added sugar also adds body fat. With the altered food product now at higher glycemic threshold, 40 percent or more of that added sugar will only turn to stored body fat after eating it. Yet consuming a more natural product, such as plain whole milk yogurt, is much less fattening.

In addition, as noted earlier, removing many fats from foods reduces your intake of essential fats and fat-soluble nutrients, especially vitamin A. And there’s the satiety factor—low- and nonfat items do not provide the fullness one obtains from a natural, healthy meal. The result may be that you eat more food because you don’t yet feel full. All this contributes to ill health and adds extra body fat.

So you need to ignore the hype, misinformation, and ongoing public relations campaign regarding fat as something evil. Instead, the real role of fat is underappreciated and ignored, usually at the expense of a person’s health and well-being.

To find out why fat should be an important part of your menu, let’s first look at whether you have a dietary fat imbalance. Just as too much fat is dangerous, so is too little.

The health survey below can help you determine your risk for dietary fat imbalance:

HEALTH SURVEY

• Does aspirin (or other NSAIDs) improve any symptoms?

• Do you have chronic inflammation (“itis” conditions such as arthritis, bursitis, tendonitis)?

• Do you have a history or increased risk of heart disease, stroke, or high blood pressure?

• Do you eat restaurant, takeout or fast food more than once or twice weekly?

• Are you carbohydrate intolerant?

• Do you follow a low-fat diet?

• Do you often have feelings of depression?

• Do you have a history of tumors or cancers?

• Do you have reduced mental acuity?

• Do you have diabetes or history of diabetes?

• Are you over age fifty?

• Do you have increased blood fats—triglycerides and cholesterol?

As with previous health surveys, if you answered any of these as “yes,” it may indicate an imbalance of fats in your diet, with more “yes” answers increasing the risk.

The term “fat” also includes oil. As one of the three main macronutrients in our diets (the other two being carbohydrates and proteins), fats are found in concentrated forms such as vegetable oils, butter, egg yolk, meats and fish, and dairy, along with nuts and seeds. Smaller amounts of fat are contained in most other natural foods including broccoli, spinach, squash, and most vegetables, lentils, and all beans.

Virtually all natural fats are healthy—but the key to optimal health and fitness is consuming them in balance. In general, eating too much of one type of fat, such as too much saturated fat from dairy products or too much omega-6 fat from vegetable oil, is an example of a fat imbalance that can adversely affect health. Balancing fats is as important as controlling carbohydrates.

In addition, eating “bad” fat—those that are artificial and highly processed, such as trans fat and those used in fried foods, can cause serious health problems. Foods such as chips, french fries and fried chicken, packaged snack foods, and restaurant items usually contain bad fat.

Natural fats have been a staple for humans throughout evolution. In fact, we would not be here today if not for dietary fat’s nutritional value. Certain dietary fats consumed in balanced proportions can actually help prevent many diseases. For instance, we now know that dietary fats are central to controlling inflammation, which is the first stage of chronic disease such as cancer and heart disease. Other common illnesses, some of which are predisease conditions, can also result from fat imbalance: cataracts, arthritis, physical injuries, osteoporosis, ulcers, allergies, and asthma.

To better understand the role of fat in one’s diet, let’s look at body fat, which is important for optimal health and fitness. But too much or too little is a problem. Stored body fat is increased and decreased several ways as shown in the chart below.

There’s no “normal” level of body fat as everyone has a unique physical body with varying needs. Below are some of the benefits of stored body fat. Listed here are some of the benefits of stored body fat:

• Forty percent or more of the carbohydrates (including sugar) you eat turns to fat and are stored.

• Most fat consumed goes into storage right away (smaller amounts are used for energy).

• Overeating protein foods can also be stored as fat.

• Physical activity burns stored body fat (especially easy aerobic exercise).

• Eating a meal, or even a snack, can stimulate body-fat burning (a process called thermogenesis) and occurs more effectively after consuming foods containing fats.

• Energy. The aerobic system depends on both stored body fat and the fats circulating in the blood as the fuel for muscles, which power us through the day. Fat produces energy and prevents excessive dependency upon sugar, especially blood sugar. Fat provides more than twice as much potential energy as carbohydrates do, nine calories per gram as opposed to only four calories. Your body is capable of obtaining much of its energy from fat, up to 80 or 90 percent, if your fat-burning mechanism is working efficiently. The body even uses fat as a source of energy for heart-muscle function. These fats—called phospholipids—normally are contained in the heart muscle and generate energy to make it work more efficiently.

• Hormones. The hormonal system is responsible for controlling virtually all healthy functions of the body. But for this system to function properly, the body must produce proper amounts of the appropriate hormones. These are produced in various glands and depend on fat for proper production—the thymus gland regulates immunity and the body’s defense systems; the thyroid regulates temperature, weight, and other metabolic functions; the kidney’s hormones help regulate blood pressure, circulation, and filtering of blood. Cholesterol is one of the fats used for the production of hormones such as progesterone and cortisone. Even if body fat is too low, problems can arise: the combination of low-fat diets and reduced body fat can cause some female athletes to experience disruptions in their menstrual cycle, and in older women, menopausal symptoms; in men, low levels of testosterone can weaken bones.

• Eicosanoids. Hormonelike substances called eicosanoids are necessary for such normal cellular function as regulating inflammation, hydration, circulation, and free radical activity. Produced from dietary fats, eicosanoids are especially important for their role in controlling pain and inflammation. Many people who have inflammatory conditions, such as arthritis, colitis, tendonitis—conditions whose names end in “itis”—probably have an imbalance of dietary fats. But in many more people, chronic inflammation goes on silently. Eicosanoids are also important for regulating blood pressure and hydration, preventing constipation or diarrhea, and can trigger menstrual cramps, blood clots, and tumor growth.

• Insulation. The body’s ability to store fat permits humans to live in most climates, especially in areas of extreme heat or cold. In warmer areas of the world, stored fat provides protection from the heat. In colder lands, increased fat stored beneath the skin prevents too much heat from leaving the body. An example of fat’s effectiveness as an insulator is in the Eskimo’s ability to withstand great cold and survive in good health. Eskimos eat a high-fat diet and, despite this, have a very low incidence of heart disease and other ailments.

In warmer climates, fat prevents too much water from leaving the body, which can result in dehydration that causes dry, scaly skin. Some evaporation is normal, of course, but fats under the skin regulate evaporation and can prevent as much as ten to twenty times more water from leaving the body.

• The brain. About 60 percent of the nonwater part of a healthy brain is fat. During our own development, the incorporation of fat into the brain—in particular the essential fatty acids including A, B, and most especially C fats—enabled us to better create, learn, remember, and grow our brains at a much faster rate. This is especially important not only for all children from birth but all adults as well.

The covering of neurons—the specialized brain cells that communicate with each other—have a high monounsaturated (oleic) fat content, the same type of fat found in olive oil, almonds, and avocados. Overall, C fats (EPA and DHA) are the most common fat in the brain.

Many brain disorders, including cognitive dysfunction such as Alzheimer’s disease, can be prevented with the right fats, and these conditions can also be treated with fats such as fish oil.

• Healthy skin and hair. Fat has protective qualities that also give skin the soft, smooth, and unwrinkled appearance that many people try to achieve through expensive skin conditioners. The healthy look of skin—and hair—comes from the fat inside our bodies. Fats, particularly cholesterol, serve as an insulating barrier within the skin. Without this protection, chemical pollutants can more easily enter the body through the skin. Hair loss starts with an imbalance of dietary fats that triggers inflammation in the scalp.

• Pregnancy and lactation. The effective functioning of fat-dependant hormones improves fertility for both would-be parents. Once conception does take place, fats continue playing a key role in the health of mother and child. The uterus keeps the newly conceived embryo thriving by providing nutrition until the placenta can begin to function, usually a period of a week or more. Adequate progesterone, a hormone produced from fats, is primary for the embryo to survive the first critical week, preventing miscarriage (spontaneous abortion). The placenta itself must also develop and produce hormones for the fetus—accomplished in large part from the rising production of estrogens and progesterone as the pregnancy continues.

Following birth, breast-feeding helps protect the baby against allergies, asthma, and intestinal problems through its high-fat content, particularly cholesterol. The baby is highly dependent upon the fat in the milk for survival, especially during the first few days. During this time, the fatty colostrum content of breast milk is of vital nutritional importance.

• Digestion. Fats play a primary role in digestion. Bile from the gall bladder is triggered by fat in the diet, which is the first step in the digestion and absorption of essential fats and fat-soluble vitamins (A, D, E, and K). Most dietary fats are digested—broken into smaller particles—in the small intestine. The pancreas, liver, gall bladder, and large intestine are also involved in the digestive process. Any of these organs not working properly could have an adverse impact on fat metabolism in general, but the liver, which makes bile, and the pancreas, producing the fat digestive enzyme lipase, are particularly important. Without sufficient fat in the diet, the start of the digestive process—the gall bladder secreting bile—would not be effective.

Fat helps regulate the rate of stomach emptying, helping protein digestion, and satisfies physical hunger by increasing satiety—the signal given to the brain that you’re full. With a low-fat meal, the brain keeps sending the same message: eat more! Because you never really feel full, overeating follows (the reason some people actually gain weight on a low-fat diet).

Fats also slow the absorption of sugar from the small intestines, which keeps blood sugar and insulin from rising too high and too quickly (recall that fat in the meal lowers its glycemic index). Additionally, fats protect the inner lining of the stomach and intestines from irritating substances in the diet, such as alcohol and black pepper.

• Body support and protection. Stored fat offers physical support and protection to vital body parts, including the organs and glands. Fat acts as a natural built-in shock absorber, cushioning the wear and tear of everyday life, and helps prevent organs from sinking with age due to the downward pull of gravity.

By controlling free radical production, fats can physically protect our cells against the harmful effects of X-ray exposure. In addition to medical X-rays, we are constantly exposed to X-rays from the atmosphere—cosmic radiation penetrates most objects, including airplanes. The average person gets more cosmic radiation exposure during an airline flight from New York to Los Angeles than from a lifetime of medical X-rays.

• Vitamin and mineral regulation. Most people know that vitamin D is produced by exposure of the skin to the sun. Sunlight chemically changes cholesterol in the skin through the process of irradiation to vitamin D3, which is then absorbed into the blood. Without the vitamin D, calcium and phosphorous would not be well absorbed, and deficiencies of both could occur. But without cholesterol, the entire process would not occur.

Vitamins A, E, and K also rely on dietary fat for proper absorption and utilization—a low-fat diet could be cause a deficiency in these vitamins. Certain fats circulating in the blood, called prostaglandins, help carry calcium into the bones and muscles. Without these fats, calcium levels in bones and muscles can be reduced resulting in the risk for stress fractures, osteoporosis, and muscle dysfunction. Unused calcium may be stored, sometimes in the kidneys, increasing the risk of stones, or in the muscles, tendons, or joint spaces as calcium deposits.

Our body fat is as important as the fat we eat. The human body possesses two distinct types of body fat, referred to as brown and white. Both are metabolically active, living parts of us. Total body fat content ranges from 5 percent in male athletes to more than 50 percent of total body weight in obese individuals. Much of the fat we consume and the fat produced from eating carbohydrates turns to white fat. It’s also our stored form of energy, used during physical activity (unless we’re not active enough, then we don’t burn it, and it remains in storage). Other attributes of white fat are protection of body parts as noted above.

Brown fat makes up only about 1 percent of the total body fat in healthy adults, with much higher amounts at birth in healthy babies. Brown fat helps us burn white fat. Without brown fat’s metabolic action, we can gain body fat and become sluggish in the winter like a hibernating animal. There are a number of ways to increase brown fat activity:

• Food frequency can affect brown fat to either increase or decrease fat burning. Eating several times a day—five to six smaller healthy meals instead of one, two, or three larger ones—can trigger thermogenesis, an important postmeal metabolic boost to increase fat burning. However, if caloric intake is too low, brown fat can slow the burning of white fat. This can happen on a low-calorie diet and when meals are skipped.

• The body’s brown fat is stimulated by certain dietary fats. These include omega-3 fats, especially from fish oil and olive oil. While supplements of fish oil may be the only way to obtain adequate amounts of EPA, some supplements can be harmful—conjugated linoleic acid (CLA) can actually reduce brown fat activity.

• Caffeine—contained in tea, coffee, and chocolate—can increase brown fat activity. But too much caffeine can trigger stress, reducing fat burning and promoting fat storage.

• Refined carbohydrates, including sugar, and other high glycemic items can reduce fat burning.

In addition to foods, stimulating brown fat can be accomplished with various lifestyle routines:

• Skin temperature. If we get too hot during the day or overdress during exercise, brown-fat activity can lead to less burning of white fat. This is why wearing extra clothes or “rubber sweat suits” during exercise, a common weightloss myth, can be dangerous.

• Likewise, soaking in a sauna, hot tub, or steam room regularly after exercise may offset some of the fat-burning benefits of physical activity. While these activities increase sweating, resulting in some water-weight loss, the sacrifice is reducing brown fat activity. Hot tubs and saunas do come with health benefits, but to avoid the reductions in fat burning take a minute or two to cool the body in a cold shower or tub afterward.

Brown fat is stimulated by cold. Most of our brown fat is found under the skin around the shoulders and underarms, between the ribs and at the nape of the neck. Cooling these areas can help increase fat burning. (These are also the specific areas to keep from overheating during exercise.)

Low body temperature is associated with reduced fat-burning. Poor thyroid function is often associated with body temperatures below the normal 98.6°F.

• Physical activity increases fat-burning too. The best kind being the easy-aerobic type, such as walking, which trains the body to burn more body fat all day and night. This issue is discussed in detail in section II.

Unfortunately, most research on brown fat comes from the pharmaceutical industry, which is looking for new drugs to stimulate brown fat. But as noted above, we already know enough healthy habits to stimulate brown fat so we can burn more white fat.

Now that you have a general understanding of healthy body fat, I want to outline how to balance your consumption of certain fats in your diet. In general, this is accomplished in three steps. The first two are simple—when using dietary fats and oils:

For cooking, use only olive oil, butter or ghee (“drawn” or purified butter), coconut oil or lard.

Avoid all vegetable oil (such as soy, safflower, corn, and peanut) and trans fat (from margarine and other processed fats and oils).

The third step is to consume omega-6 and omega-3 fats in a ratio of about 2:1. Most people consume much more omega-6 fats and have a ratio of 5, 10, or 20 to 1. This is the crucial part of balancing fats and needs much more explanation.

The issue of balancing fat consumption is quite involved. Volumes have been written on the subject, and many scientists have devoted their entire careers to this topic. But I have simplified the explanations to help you achieve this important task.

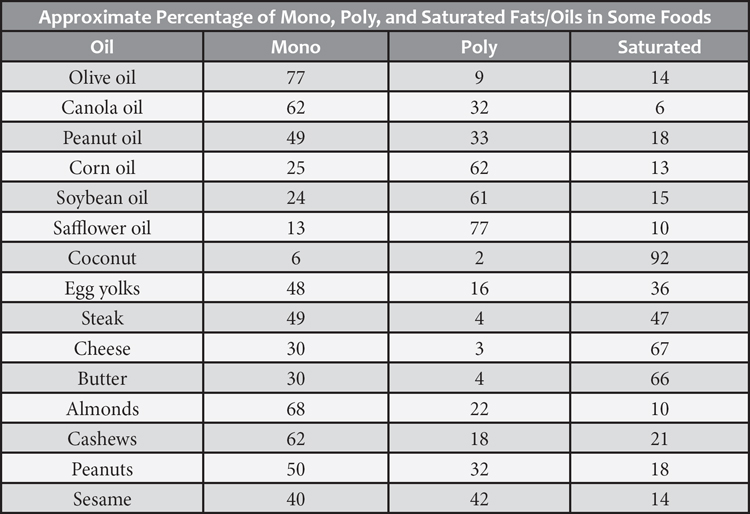

There are three common forms of fats in our diet—the differences are due to their chemical makeup. As such, they have varying characteristics for use in cooking and function quite differently in the body. These three forms of fats are referred to as monounsaturated, polyunsaturated, and saturated.

Mono fat is associated with improved health and disease prevention and should make up the bulk of fat in your diet. Mono fat—also referred to as oleic or omega-9—helps reduce the risk of cancer, heart disease, and obesity. The Mediterranean diet, with its lower incidence of ill health, is relatively high in mono fat. An example of how this fat can prevent disease is by its influence on cholesterol: it can raise good HDL and lower bad LDL cholesterol, greatly improving cardiovascular health. In addition, mono fats can help control inflammation, reduce the harmful effects of too much saturated fat, and its presence in foods is associated with phytonutrients—important plant compounds discussed in chapter 7.

Mono fat is also very stable with a naturally long shelf life. As discussed later, polyunsaturated fat is unstable and easily oxidizes and can form dangerous oxygen free radicals from exposure to air, light, and heat. Not so for mono fat. Due to its chemical structure, it’s virtually immune to oxidation, making it safe for cooking and storing without refrigeration. This is one reason why olive oil, made up mostly of mono fats, has been used as a food ingredient and in cooking for centuries in many cultures.

Mono fat is found in many foods and oils. Avocados, almonds, and macadamia nuts contain higher amounts. Olive oil is very high in monounsaturated fat and is the best oil for use on salads and in recipes.

Many foods naturally contain polyunsaturated fat. They have become a staple in the American diet. Two essential fatty acids—so named because we must consume these vitaminlike nutrients as we can’t make them in our bodies—are found in “poly” fats: they are termed “omega-6” and “omega-3.” There are varying amounts of each in different types of poly oils, and most importantly, they play a vital role in regulating inflammation and pain.

While a small amount is necessary for health, high amounts of omega-6 poly fats are potentially dangerous. They’re found in vegetable oils often used in cooking and salads and high in packaged foods. Those with the highest amounts of omega-6 fats are contained in safflower, peanut, corn, canola, and soy oil. They’re even found in infant formulas and dietary supplements.

Polyunsaturated fat is easily oxidized to chemical free radicals, making it a potentially dangerous oil. Oxidation occurs when this type of fat is heated or exposed to light and air. When we consume oxidized fat, this free-radical stress can damage cells anywhere in the body, speed the aging process, turn LDL cholesterol “bad,” and significantly increase the need for antioxidant nutrients. The fat content of most people’s diet is very high in omega-6 fats from vegetable oils.

THE MIGHTY OLIVE AND WHY IT MAKES ONE OF THE BEST COOKING OILS

History tells us that olives were native to the Mediterranean region over five thousand years ago. The olive tree may be the oldest cultivated plant. In addition to its use as food, the oil from olives became a staple for the people in the region, and eventually the world.

The best olive oil to use is the least processed and most nutritious—organic extravirgin olive oil. My favorites are from Italy, Spain, and Greece. The “first-press” oil is obtained from the whole fruit without heat or chemicals. The highly nutritious phytonutrients, especially a group of compounds called phenols, are abundant in this oil, which gives it a light bitter taste and dark green color. Much lower amounts of phenols are present in other grades of olive oil not labeled as extravirgin.

Most countries that produce olive oil adhere to the International Olive Oil Council (IOOC) standards when it comes to classifying their products. While the IOOC has a United Nations charter to develop criteria for olive oil quality and purity standards, the United States has not adopted them. The USDA, which allows lower quality olive oil to be sold, still uses a 1948 classification system (although this is expected to someday change).

An important IOCC criterion for olive oil is that it cannot be diluted with nonolive oils, and must conform to sensory and analytical standards. The oils must be obtained directly from the olive fruit without the use of solvents or other chemicals.

The highest quality olive oil is labeled as organic and extravirgin olive oil. Only about 10 percent of the oil produced is extravirgin (I have no data on how much of this is certified organic). This oil can vary widely in taste, color, and appearance, much like fine red wines. Choose a brand that meets your taste.

Other products labeled as olive oil or pure olive oil are not extravirgin and of lower quality. Those labeled as light or extralight are examples of marketing gimmicks, are very low quality, and should be avoided.

One way to make poly fat work toward optimal health, rather than contributing to functional problems and disease, is to balance the consumption of omega-6 and omega-3 fats. To accomplish this, avoid all vegetable oils and processed food because they are generally high in poly fat; instead, use extravirgin olive. Before discussing this issue in more detail, let’s discuss saturated fat because it’s part of the balancing act.

Of all the dietary fats, the saturated form is always considered the worst. But saturated fat is important for energy and hormone production, cellular functioning, and optimal brain function.

Saturated fat, like the poly form, is made up of many different fatty acids of varying attributes. Here are some:

• Palmitic acid is found in high amounts in dairy fat—in milk, cheese, cream, yogurt, and butter. It can raise cholesterol. Palmkernel oil is also high in palmitic acid, but palm fruit oil is not and actually can lower LDL cholesterol. Some of the dietary carbohydrate that converts to fat become palmitic acid. High blood levels of palmitic acid may predict type 2 diabetes, heart disease, stroke, and carbohydrate intolerance. But it’s not the presence of palmitic acid that’s the problem—when all fats are balanced, palmitic acid does not seem to be such a health problem.

• Arachidonic acid—AA—is another fatty acid that gives saturated fat a bad name. Small amounts of AA are essential for health, especially for the brain, the fetus, newborns, and growing children. But too much AA is very unhealthy. These fats are found in dairy, egg yolks, meats, and shellfish. But these foods are not nearly the problem compared to the high amounts of omega-6 fat in the diet, commonly found in vegetable oil, because this fat can be converted in the body to AA. The result can be chronic inflammation, bone loss, and increased pain. As discussed below, AA plays a key role in balancing fats.

• Stearic acid is another fatty acid found in saturated fat. It has various health benefits on the immune system. Foods containing higher amounts include cocoa butter and grass-fed (but not corn-fed) beef. And stearic acid can be converted to healthy mono fat.

• Lauric acid is a fatty acid that plays an important role in energy production, and it has antiviral and antibacterial actions, especially in the intestine (and the stomach in particular, against Helibacter pylori). Coconut oil, high in saturated fat, has high levels of lauric acid (and contains very little polyunsaturated fat), making it an ideal fat for cooking.

In animal foods, which contain relatively high amounts of saturated fat, the most important factor that determines the level of healthy fatty acids is the food consumed by the animal. As noted above, grass-fed beef contains a much healthier content of fatty acids compared to corn-fed beef. For the same reason, wild animals usually contain healthier fatty acid profiles than animals that are fed grain in confinement. In plants, the soil plays a certain role in determining fatty acid content, with natural fertilizers a healthier choice over chemical types.

Mono, poly, and saturated fats are found in most foods. A few foods contain predominantly one type of fat or another, but most contain a combination of all three fats. Many people are surprised to learn, for instance, that the fat in an average steak is about half monounsaturated and half saturated, with a small amount of polyunsaturated.

While it might first appear to be an excessively complicated subject, balancing your dietary fats is as easy as learning the ABCs. I developed this model in the mid-1980s, as a way to teach health care professionals about the subject of fat balance, for patients to implement the ideas, and in my own published articles on the subject.

There are three fatty acids that require balance for optimal health. I mentioned them above—they are omega-6, AA (arachidonic acid), and omega-3. I’ll refer to these three as A, B, and C fats, respectively.

| The ABCs of Fat | ||

| A Fat | B Fat | C Fat |

|

|

|

| omega-6 | AA | omega-3 |

In the body, the A, B, and C fats influence inflammation: the A and C fats are anti-inflammatory in their function; the B fats trigger inflammation.

Actually, inflammation is only one of the concerns. Without sufficient anti-inflammatory chemicals (from A and C fats), one could develop chronic inflammation—this is the first step to other functional problems and disease, including cancer, heart disease, Alzheimer’s, diabetes, and any of the “it is” problems prevalent in our society—from arthritis and tendonitis to colitis and sinusitis. In addition, too many B fats can cause bone loss, muscle imbalance, allergy and asthma, and menstrual problems. And B fats can also increase pain.

The A and C fats can counter all these problems, preventing disease, ill health, and reducing pain.

This is a key factor in optimal health and fitness: the balance of A, B, and C fats in the diet. But before explaining the details on how to do it, allow me to go a bit deeper in this explanation—it’s very important.

In the body, the A, B, and C fats are converted to three respective groups of hormonelike substances called eicosanoids (pronounced i-cos-an-oids). I’ll call these groups 1, 2, and 3. Basically, A fats make group 1 eisosanoids, B fats group 2, and C fats group 3.

Eicosanoid balance is so powerful—so influential to overall health—that billions of dollars are spent by pharmaceutical companies to research and develop new drugs that attempt to balance the eicosanoids. But you can do it cheaply by eating the right foods! And while drugs that attempt to balance fats have some short-term success, they come with significant unhealthy, and sometimes deadly, side effects. Aspirin and other NSAIDS are the best example—while reducing the inflammatory chemicals made by the B fats (and group 1 eicosanoids), one side effect is that the natural anti-inflammatory eicosanoids are also impaired. But balancing fats by eating right only has healthy—and nearly miraculous—benefits.

| The ABCs of Fats | ||

| A Fats | B Fats | C Fats |

|

|

|

| Group 1 | Group 2 | Group 3 |

| eicosanoids | eicosanoids | eicosanoids |

The term “eicosanoid” refers to a group of different compounds with names such as “prostaglandins,” “leukotrienes,” and “thromboxanes.” They’re involved in complex reactions from moment to moment in all cells throughout the body. For now, just remember that balanced eicosanoids, from balanced fats, regulate certain bodily functions that are central to optimal health and fitness, elimination of functional problems, and disease prevention. With this in mind, understanding how to balance the A, B, and C fats, and the 1, 2, and 3 groups of eicosanoids is vital. First let’s discuss the foods that contain the A, B, and C fats.

A fats are most prevalent in vegetable oils: safflower, soy, corn, peanut, and canola. These omega-6 fats contain an important fatty acid called linoleic acid that I’ll call LA for short. LA is an essential fatty acid because the body can’t make them and we must eat foods containing them. When we do, LA is converted to other fats, including GLA (gamma-linolenic acid), with the end result being the series 1 eicosanoids with anti-inflammatory effects. In addition to vegetable oils, common dietary supplements of omega-6 products include black currant seed, borage, and primrose oils that contain high amounts of GLA. While the group 1 eicosanoids from A fats can produce powerful health effects, there is one potential problem. Conversion of A fats to group 1 can be impaired resulting in many A fats being converted to B fats.

A variety of factors can cause this to happen: reduced levels of nutrients (niacin, vitamin B6, magnesium, protein), consumption of trans fats, and excess stress. This can more easily occur as we age. The remedy? Eat the best diet possible to ensure you obtain all the nutrients, avoid bad fats and moderate stress (a topic discussed in chapter 19). When this happens, the aging factor will be minimized.

The B fats are sometimes considered bad because of the effects they can have in the body. But these effects are only bad when in excess—in other words, not balanced with A and C fats. As noted, B fats promote inflammation and pain. But these so-called problems can actually be important for health at the right time—inflammation is a vital first stage of the healing process, and the body uses pain to help us become more aware of a problem so we can remedy it. Another important function of AA is that it’s very important for the repair and growth of the brain. This is especially vital in the fetus, newborns, and developing children; but as adults, we continually should be repairing and growing the brain as well. B fats are highest in dairy products such as butter, cream, and cheese, and in lesser amounts in the fat of meats, egg yolks, and shellfish. However, for most people, the largest source of AA is from A fats.

The C fats, omega-3, and are found mostly in ocean fish, with lesser amounts in beans, flaxseed, walnuts, and wild and grass-fed animals. These fats contain ALA (alphalinolenic acid), an essential fatty acid that is converted in the body to EPA (eicosapentaenoic acid), with the final production of group 3 eicosanoids. This conversion can be impaired by the same problems that impair the conversion of A fats to group 1 eicosanoids—poor nutrition, trans fat, stress, and aging. Ocean fish already contain EPA and are very useful as a dietary supplement for people who require more omega-3 to balance fats. Flaxseed oil does not contain EPA, and while the body may convert some of it to EPA, it’s very inefficient. EPA also exists in conjunction with another important fatty acid, DHA, which is especially important for the fetus through childhood.

It’s relatively easy to balance A, B, and C fats. It can be accomplished first by eating approximately equal amounts of foods in the A, B, and C categories. It does not necessarily have to be at each meal, but in the course of a day or week, balance is of prime importance.

By eating a balance of A, B, and C fats, you’ll consume polyunsaturated (A and C) and saturated (B) fats in the optimal ratio of 2:1. In the typical Western diet, many people consume ratios of 5, 10, or even 20:1! It’s no wonder there’s an epidemic of chronic inflammation, pain, and disease. (If you don’t eat meat or dairy, consume approximately an equal ratio of A and C fats; in this case, some of the A fats will convert to B fats.)

Fat imbalances typically occur from some combination of eating too much A or B fats, and too little C fats, by a lack of certain nutrients, stress, and aging. But a significant cause of imbalance is from refined carbohydrates including sugar. Recall that insulin can be produced in higher amounts when these carbohydrates are consumed. This causes more A fats to convert to B fats—enough said!

Two foods can help prevent too much A fat from converting to B fats. These are as follows:

• EPA found in raw ocean fish or in fish-oil supplements. Fish should be cooked very lightly as EPA is an unstable poly fat.

• Raw sesame oil, which contains the phytonutrient sesamin. Heated sesame oil will not accomplish this task (and is a very unhealthy food as the sesamin becomes sasamol, a potential cancer-causing agent).

If all this sounds too complicated, it’s not. Here’s how one my patients, Mary, succeeded in making the appropriate dietary changes to balance her fats and change her life. Mary had chronic health problem ever since around the beginning of high school. At first, with vague symptoms of intestinal distress, the family doctor found nothing from an initial examination and concluded there was no reason to perform other tests—he thought she would outgrow the discomfort. By college, Mary had bouts of being severely run down with exhaustion, periods of acute intestinal pain, and muscle dysfunction that caused weakness and numbness. As an active athlete in high school, she was unable to work out in college because it made all her symptoms worse. Eventually, an extensive evaluation was made as her condition worsened. But no definitive diagnosis could be made. One specialist after another gave an opinion—and a name for a particular condition—from Crohn’s disease and ileitis (two common intestinal conditions) to rheumatoid arthritis and Lyme disease.

Mary visited my clinic four years after finishing college, having tried many diets, drugs, and dietary supplements without success. I retrieved as many copies of her past evaluations from her family doctor that included blood and urine tests, reports by radiologists, neurologists and gastroenterologists, and a psychologist. The only revealing factor in the more-than-fifty pages of reports was a test that showed a moderate amount of inflammation—a C reactive protein test was moderately high—the reason so many doctors wanted to pin the name of some inflammatory condition on her.

In my dietary analysis, I was able to evaluate the balance of her A, B, and C fats—she consumed very high amount of A fats, using safflower oil for all her cooking and daily salads; ate small amounts of B fats, mostly a few eggs a week with one or two meals containing some type of meat; and she ate no fish or other sources of C fats. Her balance of fats was quite bad—excessive amount of A fats, moderate B fats, and little if any C fats. But from her recollection, Mary’s diet was much worse growing up. This part of her history made sense considering when her problems began (during high school).

Here is a synopsis of the dietary recommendations I gave to Mary:

• Eliminate all vegetable oils—replace them with extra virgin olive.

• Eliminate all packaged foods, which often contain vegetable oils.

• For cooking, use only coconut or olive oil, or lard.

• Reduce restaurant and takeout food—limit it only to healthy, whole food items such as salads with olive oil, eggs, and meats that are lightly cooked without vegetable oil (butter, coconut oil, or lard was okay).

• Reduce all refined carbohydrates, including foods containing them.

• Avoid all trans fats such as margarine and similar items and foods that contain them.

• Limit all dairy to one serving three times weekly. This included butter, cheese, milk, cream, and yogurt.

• Increase fresh vegetables to ten servings per day.

• Increase protein intake—two times daily have one serving of eggs or any type of meats (unprocessed).

• Use raw sesame seed oil—one tablespoon each day on a salad.

• Take four capsules of fish oil containing EPA each day (daily dose of EPA = 1,200 mg).

The goal for Mary was to balance her dietary fats. Since she did not like eating fish, I told her to get EPA from a fish oil supplement as noted above. I saw Mary about a month later, and she was happy to report about a 50 percent improvement in her symptoms. I explained this would have come mostly from getting more nutrients in her diet—especially vitamins, minerals, and proteins to help the balance of fats—and from reducing refined carbohydrates, both of which would help improve fat balance. Significant changes in the body’s fat metabolism would take another month—the bad fats in the body literally can take that long to be replaced by good ones. By the second month, Mary continued improving quite well, and by month 3, 90 percent of the complaints had disappeared. She claimed to hardly remember feeling this well. After about six months, Mary had no complaints. Butter and other dairy were allowed back into the diet in moderate amounts. The fish oil dietary supplement was reduced by half but would be maintained indefinitely as Mary did not consume any fish or beans.

Equipped with the knowledge of how important balanced fats are for the body, you are now in a position to dramatically improve your health and fitness by making some important dietary changes. This includes reduction of foods that contribute to group 1 eicosanoids, such as vegetable oils, and increasing omega-3 fats such as fish and fish oils. But how much total fat should be in a healthy diet? That amount depends on the individual and his or her particular needs.

You must first get over the idea that the less fat the better, or a diet that’s 10 percent or 20 percent fat is ideal. Actually, a low-fat diet can be very unhealthy. Studies even show that people following a very low-fat diet can increase their risks for heart disease. This is due to the fact that their intake of essential fatty acids could be too low. On the other hand, there are populations whose intake of fat exceeds 40 percent, including people living in the Mediterranean region, and healthy Americans who on average are healthier than people who eat a lower-fat diet. In addition, the American Heart Association, the World Health Organization (WHO), the U.S Surgeon General, the USDA, and many other professional health organizations have recommended a diet that’s 30 percent fat, not one that’s 20 percent or even 10 percent.

Over the years, I have found that most people are healthier with at least 30 percent fat in their diet. Some may need more—35 or even 40 percent. But rather than follow these or any other grams, calories or percentages, experiment and find what works best for you. First, focus on finding your optimal level of healthy carbohydrates. Then balance your fats. As you go through this process, the amount of fat you consume will naturally fit your particular needs.