He was tall—at six foot two he towered over most Comanches—erect, and dignified, with piercing gray-blue eyes. The height and the eye color were inherited from his white mother, but the rest was all Comanche. In photographs, he always looks solemn and intense, posing on his horse or in the buggy he used to travel with his wives and children.

“He was a fine specimen of physical manhood, tall, muscular and straight as an arrow … the envy of feminine hearts,” wrote his cousin Susan Parker St. John after meeting him in 1886. “Quanah looked you straight in the eyes; had dark copper skin, perfect white teeth with heavy raven black hair. This he wore hanging in two rolls wrapped around with red cloth. He parted his hair in the middle with a scalp-lock, the size of a dollar, plaited and tangled, hung down in front, signifying: If you want a fight, you can have it.”

The grass money deals solidified Quanah’s position as a classic middleman between the two worlds—enriching himself even as he protected his community—and made him more of a magnet for resentment and criticism from fellow Comanches. The more they needed him, the less they liked him. And his racial origins—half-white, half-Comanche—compounded his rivals’ distaste.

There were death threats: Quanah eventually built a barbed-wire fence around his home for protection. And he was quick to go on the offensive, seeking to taunt a rival chief into a showdown. “Quanah Parker started the fight by slapping Lone Wolf, but the latter did not move,” one newspaper reported. “Then Quanah hit Lone Wolf over the head with a six-shooter, but still the Kiowa chief refused to offer resistance or strike back at his assailant. Nothing Quanah would do would provoke Lone Wolf to fight.”

There were many conflicts of interest: agents, squaw men, and interpreters who worked for the cattlemen directly or otherwise stood to profit from the deals—Quanah among them. He drew a minimum of thirty-five dollars per month on Colonel B. B. Groom’s payroll, plus Groom’s promise of five hundred head of cattle. The cattlemen also kept Quanah loyal by gifts and junkets to Dallas and Fort Worth. He shared this largesse, of course, with family members and with the tribe at large. But like a shrewd middleman, he always took his cut.

Burk Burnett invited Quanah and his men frequently to Fort Worth to appear in the annual Fat Stock Show. “There is one thing that you can say to all the Indians,” Burnett wrote to Quanah. “That they will have a bully good time and not be out a cent of their money, as all expenses are to be paid coming and going and while they are here.”

In 1883 the Fort Worth Gazette reported on one such visit. Its correspondent noticed a large, swarthy, well-dressed man with flowing black hair sitting by the fireplace of the Commercial Hotel. The man was dressed in a black cashmere suit, and wore a large white hat, a fine pair of boots, wrist-warmers, a gold watch and chain, and a stiff collar and cravat. He sat for an hour and spoke not a word, until the hotel owner’s little girl came up to him, “when he commenced stroking her hair softly and speaking in a low soft tone to her.”

Quanah had just been to visit with his cousin I. D. Parker, the oldest son of Isaac Parker, the uncle who brought Cynthia Ann “home” to Texas. Isaac had died eight months earlier, at age eighty-nine. This visit marked the first time a white member of the far-flung Parker clan had agreed to meet with Quanah. After they met, I.D. placed a newspaper notice on Quanah’s behalf seeking a copy of the photograph taken of Cynthia Ann and Prairie Flower in Fort Worth in 1861. The legend of Cynthia Ann Parker, dormant for more than a decade, was beginning to reassert its power, thanks to the ardent efforts of her surviving son.

Quanah extended his personal generosity to all his white relatives. Knox Beal’s mother was one of Cynthia Ann’s cousins. As a young man Beal worked for a traveling circus and was suffering from a bout of extreme homesickness when he met Quanah outside San Antonio in 1884. Quanah invited Beal to come live with him in Oklahoma, and Beal remained there for some six years, eventually settling permanently in the area. “He certainly was a wonderful friend and counselor to me,” Beal would recall, “and I have never regretted the day I came home with him.”

Soon after, with Indian agent Hunt’s enthusiastic support, the Bureau of Indian Affairs formally recognized Quanah as “chief” of the Comanche nation. Comanches had always been a loosely knit group of communities that shared language, customs, and kinship ties, but they had never recognized any one leader as their chief. Many were not happy when Quanah accepted this role; some denounced him as a usurper and a white stooge. None of this deterred him. But he yearned for a substantive symbol of his new position.

A great chief, Quanah decided, needed a great house.

QUANAH FIRST PROPOSED the idea to Philemon Hunt in 1882. Originally he had in mind a simple two-room structure like the ones many Comanches were building in the pastures near Cache Creek. But as Quanah’s stature grew, his idea evolved into something far grander: a house of unprecedented size for an Indian that would overlook the cabins, teepees, and lodges of his fellow Comanches. His repeated efforts to extract money from Washington for the project were rejected or ignored. Indian commissioner Thomas J. Morgan, a fervent Baptist, told the new Indian agent, Charles E. Adams, that the idea was a nonstarter. “While at your agency I stated to you personally that I did not deem it wise for the government to contribute money to assist in building a house for an Indian who has five wives,” Morgan wrote. “I do not think the proposition admits of discussion.”

For the next eight years Quanah remained in his teepee, moving to the traditional bush arbor in summer. But he never abandoned the idea of presiding over a big house. With Burk Burnett’s help, Quanah bought a thousand dollars’ worth of lumber in Texas, had it shipped in wagons across the Red River, and contracted for a grand two-story, ten-room house. It took two years to build, and Quanah estimated the cost at $2,000. No one ever offered a definitive account of who paid for what.

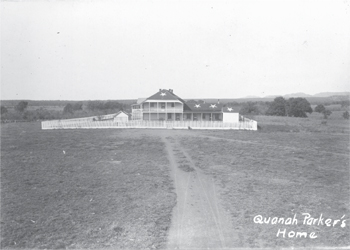

The Star House became Quanah’s showcase and seat of power. Sitting by itself atop a slight ridge on an empty stretch of pasture, it was an unmistakable monument to the man who lived within. He insisted upon painting twelve stars on the roof so that he could outrank any general who came to visit. Each year the two wings of the house seemed to grow in length as Quanah added rooms for his seven wives and nineteen children and also for the many hangers-on, white and red, whom he collected as he and his entourage traveled through Oklahoma and Texas.

The Star House, built by Quanah Parker, on the grounds of Fort Sill, outside Cache, Oklahoma, ca. 1911.

Quanah wined and dined countless guests in the long dining room, including Theodore Roosevelt and James Bryce, the British ambassador to the United States. He even played host to Geronimo after the old Apache war chief was transferred to Fort Sill from a prison camp in Florida. Neda Parker Birdsong, one of Quanah’s daughters, recalled Geronimo’s first visit to the Star House: “On the table at dinner was a big bucket of molasses. Geronimo dipped in and liked it so much that he appropriated the bucket and spooned every bit of it up.”

Quanah, who prided himself on following the traditions of Comanche hospitality, used the Star House to prove to his white guests that he was indeed “civilized.” C. H. Detrick, a prosperous Kansas merchant, arrived unexpectedly late one evening with a party of fellow businessmen. Quanah invited them in and, hearing they had had no dinner, roused his household and ordered up a hearty meal of steak, potatoes, biscuits, honey, and butter. He put the men up for the night and then fed them breakfast the next morning. “In doing the honors of his home, his manners were as finished and courteous as those of a grand gentleman, which he, indeed, was,” Detrick would recall.

Some whites never overcame the suspicion that the hostile Indian raiders who had once ruled the plains and their nightmares were waiting for an opportunity to rise up and strike again. New Indian uprisings became a staple of press coverage. “Comanches on the War-Path” read a typical dispatch in the St. Louis Globe-Democrat in March 1886, accusing Quanah and an alleged band of 1,300 men, women, and children of invading North Texas, setting wildfires and killing 40 to 50 cattle.

Quanah Parker on the porch of his new house, ca. 1890.

To allay white fears, Quanah was willing to play the role of enforcer of the white man’s laws and rules on the reservation. When it suited his purpose, he even played the informer. In a note dated April 7, 1887, handwritten for him by his son-in-law Emmett Cox, Quanah warned Captain Lee Hall, the chief Indian agent in Anadarko, that Kiowa leaders “had been making medicine on Elk Creek” and had decided “to make a war break on Fort Sill in the middle of the summer.” They asked Quanah to join with them. “Me and my people have quit fighting long ago and we have no desire to join anyone in war again,” wrote Quanah, who signed the note “respectfully, Quanah Parker.” Two years later, when the government established a “Court of Indian Offenses,” Quanah was appointed presiding judge, a position that gave him formal police powers and the right to adjudicate disputes.

In the early 1890s the Ghost Dance craze, which began among Sioux Indians in the Dakotas, set off a wave of panic in Oklahoma and the Texas Panhandle. Indians, despite their recent exposure to Christianity, reverted to their barbaric, animistic past, or so many whites believed. One night in 1891 a group of ranch hands in Collingsworth County, Texas, fired off several shots to kill a steer, which rampaged blindly through their encampment and toppled the campfire. A woman in a nearby settler’s dugout heard the shots and the yelling and saw the smoke. Assuming it was Indians, the panic-stricken woman saddled her horse, took her two babies to a nearby farm, and triggered an alarm that spread from Clarendon to Amarillo. Townsfolk built barricades and wagonloads of settlers poured into towns from the rural areas seeking shelter from a Red Peril that did not exist. It took several days for calm to return.

Quanah and his moderate Kiowa ally, Apiatin, worked hard to convince their fellow Indians that the Ghost Dance had no value. Apiatin even journeyed to the Pine Ridge reservation in South Dakota to meet the purported messiah behind the movement, and reported back to Oklahoma that the man was a fraud.

The same kind of panic occurred in 1898 at the start of the Spanish-American War, when most of the garrison at Fort Sill was ordered to report to the Gulf Coast on short notice, leaving only twenty-one soldiers at the fort. A rumor soon spread that Geronimo and the handful of Apaches who were living on the grounds were planning to rise up and seize the fort. In response, Quanah rounded up his own men and set up a protective ring around the fort’s corral and guardhouse. The panic soon dissipated. But the Apaches were bemused to see Comanches—the former Lords of the Plains—mobilized to protect a U.S. Army facility from other Indians.

THE SAD TRUTH was that when it came to whites, Indians had more to fear from their friends than from their enemies. It was their friends, after all, who sought to destroy Native American culture, belief systems, language, and family structures, and seize control of the upbringing and education of Native American children, all in the name of progress and the Indians’ own best interests.

Former warriors and hunters were expected to become docile farmers. Their children were required to attend government schools where their Comanche identity, culture, and language were banned or denigrated. Christian ministers, seeking to save souls, challenged the Comanche animistic faith and their practice of polygamy. Even their diet came under attack: Thomas J. Morgan, the chief Indian commissioner, sought to ban the eating of blood and intestines—“a savage and filthy practice,” he wrote in a letter to subordinates. “It serves to nourish brutal instincts and … [is] a fruitful source of disease.”

For Quanah, Morgan was a formidable opponent. A devout Baptist schoolteacher from Indiana, he had served as a commander of African-American troops during the Civil War, and he saw himself as a champion of racial equality. But his notion of equality was total assimilation: Indians, like Negroes, needed to lose their identity as a distinctive ethnic group and become proper little white folks. He even banned Indian participation in Wild West shows, believing that the exhibitions helped sustain the stereotype of the bloodthirsty savage that Indians needed to overcome.

“The Indians are destined to be absorbed into the national life, not as Indians but as Americans,” Morgan wrote to Indian agents and school superintendents throughout the country. “In all proper ways teachers in Indian schools should endeavor to appeal to the highest elements of manhood, and womanhood in their pupils … and they should carefully avoid any unnecessary reference to the fact that they are Indians.”

Reformers such as Richard Henry Pratt, a former army officer placed in charge of Kiowa and Comanche prisoners sent to Florida after the Red River War, were openly determined to destroy Indian culture. As Pratt put it, the goal was to “kill the Indian and save the man.” Pratt founded the Carlisle School in Pennsylvania, which became the best-known of the many Indian boarding schools. He dressed his charges in “civilized” outfits—high-buttoned coats and stove-pipe trousers for the boys, dresses and smocks for the girls—chopped off their braids, and banned their native languages. This was ruthless pragmatism in the service of a higher good, according to Pratt: “The sooner all tribal relations are broken up; the sooner the Indian loses all his Indian ways, even his language, the better it will be for him and for the government and the greater will be the economy for both.”

Faced with this cultural onslaught, Quanah fought a careful rearguard action. He was willing to accept white religion and education, but was determined to preserve Comanche culture and identity. He authorized Christian missionaries to open churches and schools in Comanche territory, but only those who first came to seek his permission. He eventually sent his own children to white-organized schools, both the Fort Sill Indian School locally and the Carlisle Indian Industrial School.

In time, Quanah came to believe that Indian children needed to learn the same skills as whites if they were to survive in a white-dominated world. “Me no like Indian school for my people,” he said. “Indian boy go to Indian school, stay like Indian; go white school, be like white …”

All of this became part of the image that Quanah carefully constructed as a reformed warrior who was ready and willing to travel the white man’s road. “Like slaves on a plantation, the Comanches quickly learned, and none better than Quanah, the necessity of telling the white man what he wanted to hear, while preserving as much of the old way of life as possible,” wrote the historian William Hagan.

Still, there were parts of Quanah’s life that he refused to compromise or change. While he wore business suits in public, he would not cut off his warrior braids. Similarly, he refused to abandon polygamy, arguing that it was an essential part of the Comanche way of life. When asked by an official to provide leadership by choosing one among his wives, Quanah teased that he himself was willing to pick one, “but you must tell the others.”

His first wife was To-ha-yea, a Mescalero Apache, but the marriage quickly unraveled. Next he married Weckeah (“Hunting for Something”), the woman he had eloped with back in the 1860s. Their daughter Nahmukuh married Emmett Cox, the white ranch hand whom Quanah helped to get a job at the Indian agency and who became one of Quanah’s most trusted advisers. Then came Cho-ny (“Going with the Wind”), followed by A-er-wuth-takum (“She Fell with a Wound”), each of whom had four children. By 1892, Quanah had six wives and seventeen children. Each wife had a specific set of household duties focused on the Star House. One handled his personal papers, one took care of his riding horses, one was in charge of his clothing, one ran the kitchen, and one carried water, chopped wood, and cleaned the yard. Each had her own room on the main floor and took turns sharing Quanah’s bed, while the children slept upstairs dormitory-style.

Quanah, by all accounts, took delight in his children’s accomplishments, especially the literacy and education of his daughters. Several of the girls served as his personal secretary over the years, writing his letters and keeping track of the books. There are no stories of him beating or otherwise abusing his children, and many tales of his care and concern. When his son White got into trouble at the Chilocco Indian school in northern Oklahoma and was confined to the guardhouse, Quanah wrote to the superintendent, S. M. Cowan: “I cannot, Mr. Cowan, ask you to turn him loose even if it could be done that way, but I do want you to wire me if he is ill during his confinement.” He added, “I want you to make a good boy out of him if you can …”

Still, there were times when Quanah’s public mask slipped, giving a glimpse of the man hiding behind it. For several months he met clandestinely with a young Comanche woman named Tonarcy—she quickly earned the nickname Too-Nicey—who had been married off as a young girl along with her sister to Cruz Portillo, an older Comanche. Tonarcy pleaded with Quanah to allow her to come live with him at the Star House, but he warned her that her husband would kill her if she did. This was no idle threat: when Cruz had suspected another man of paying too much attention to one of his wives, he arranged to have the man killed, according to Comanche lore.

One night after a quarrel with her husband, Tonarcy knocked on the window of Quanah’s bedroom on the first floor of the Star House. He did not let her in but sent her down the road to the home of his sharecropper, David Granthum. The following day, Quanah headed off in his buggy without telling anyone. He picked up Tonarcy and rode to a nearby ranch of white friends, then crossed the Red River to the small Texas town of Vernon and rode on to Mexico. At first his wives and friends feared he had been murdered. But when Tonarcy’s husband reported her missing as well, the truth became obvious.

The incident inflamed Quanah’s enemies among the Comanches. “Now it’s time to kill that white man,” one of them said, referring to Quanah’s mixed blood. “He’s caused enough trouble, and now it’s getting worse.”

The Mexico trip became a key moment in the Quanah Parker legend. Some storytellers say it was on this trip that he first became acquainted with peyote and its healing powers and brought this strong medicine back to his people. Others contend that Quanah and Tonarcy found a haven at the Mexican ranch of his uncle John Parker, Cynthia Ann’s younger brother, who had purportedly settled there with his wife after failing to find a home in either Texan or Comanche society. Neither of these tales is even remotely documented.

What is clear is that after several weeks, agents for the United States and Mexican governments tracked down Quanah and convinced him to return home. When he and Tonarcy came back, his wives were furious. Weckeah packed her clothes and children and stormed out, never to return. The other wives, angry but wary, forced him to cede to them a large proportion of his horses, cattle, and other possessions. He also had to pay Tonarcy’s aggrieved husband a team of horses, a buggy, and one hundred dollars cash. Tonarcy moved into the Star House, married Quanah in September 1894, and became his “show wife,” the one he took on trips to Washington and other cities. Tonarcy was unable to have children, and so a few years later Quanah added yet another wife, Topay (“Something Fell”), with whom he had three more children.

The press was fascinated by the beauty and multiplicity of Quanah’s wives. It fit the white notion of the Indian as a sexually voracious animal with no sense of moral decency—the same psychosexual theme underpinning the captivity narrative. A correspondent for the Daily Oklahoman retold the tale of the elopement with Tonarcy and described in loving detail her appearance and the apparent wealth of her husband as if they were American nobility: “The seventh Mrs. Parker is one of the finest Indian women in America and Chief Parker is proud of her … He never allows her to go out of his sight … She wears a blue velvet waist with what is known as a bat wing cape and moccasins that are very rich. The costume which she wore the last time she was here cost, it is said, over $1,500, the beads and other ornaments being very costly.”

THE PEYOTE PLANT is a small, spineless cactus found mostly in northern Mexico and South Texas. It contains a powerful hallucinogen whose effects can be relaxing and euphoric. Accounts of the original Spanish explorers to the region describe native peyote rituals of frenzied dancing with knives and hooks. From its earliest days in Mexico, leaders of the Catholic Church saw peyote worship as an idolatrous evil that needed to be eradicated. They never quite succeeded.

In their longstanding raiding and trading forays into northern Mexico, Comanches and Kiowas were exposed to peyote and its spiritual and medicinal powers. But it seems to have gained traction among these tribes only after they were consigned to the reservation. A new generation of prophets and holy men emerged who blended Christian theology with traditional Native American music and rituals. John Wilson, a Caddo-Delaware, recounted a vision in which Christ took Wilson down the road he had walked after the crucifixion from his tomb to the moon on his way to heaven. Those who traveled the Peyote Road, preached Wilson, would themselves follow Christ to heaven.

Peyote worship was a direct result of white man’s demands and innovations. The reservation system threw Comanches and Kiowas together with Mescalero and Lipan Apaches who had practiced peyote worship and brought the rituals to the reservation. Quanah first learned these rituals from two Apaches who ran all-night meetings in a big teepee with a fire pit in the middle. And it was a technological breakthrough, the railroad, that facilitated the introduction of peyote worship by enabling Indians to travel efficiently to Mexico and bring back dried peyote buttons. The loss of their old way of life and their difficulties in adjusting to reservation life created a spiritual void for many Indians. Some turned to Christianity for answers. But others found peyotism more in keeping with their spiritual identity. It was, above all, uniquely theirs, not another forced import from the white world.

Quanah helped introduce peyote to his tribe, protected it from those seeking to ban it, and preached about its healing powers even while maintaining friendships with white Christian missionaries and officials who opposed it. Even when it came to myths and legends, Quanah was willing to split the difference, blending Christian ritual with Indian traditions. “The white man goes into his church house and talks about Jesus,” said Quanah, “but the Indian goes into his teepee and talks to Jesus.”

In 1888, Special Agent E. E. White posted a written order prohibiting the use of peyote. White anticipated resistance, but Quanah paid him a visit claiming to carry a message from the other chiefs and headmen expressing their understanding that White “had taken the step solely for their own good and that they had almost entirely quit using [peyote].” White was not immovable, and Quanah quickly learned how to move him. Two months later White reported that he had reached an agreement with Quanah “to permit Indians to use peyote one night at each full moon for the next three to four months” until the supply ran out. Apparently it never did.

James Mooney, an Indiana newspaper reporter who became an ethnologist for the Smithsonian Institution, attended several all-night peyote rituals in the early 1890s. He was allowed to participate, he wrote, “so that on my return I could tell the government and the white men that it was all good and not bad, and that it was the religion of the Indians in which they believed, and which was as dear to them as ours to us.”

Still, to many whites, peyote was just another way for Indians to get high. J. J. Methvin, a Methodist missionary who befriended Quanah, approached a teepee near the agency one evening and found two of Quanah’s wives stretched out on the grass. When he asked what was going on, one of them motioned for him to enter the tent. He took a seat among a circle of worshippers who had their eyes shut tight and were beating tomtoms, rattling gourds, and chanting wildly. “Quanah opened his eyes and discovered me; he smiled his recognition and welcome.”

Quanah explained that peyote helped Indians be inspired by the Great Father, just as whites were inspired from the Bible. “All the same God, both ways good,” he told Methvin. But the preacher was not buying this line. “This is not the Indian’s old religion and indeed cannot properly be called a religion at all,” Methvin wrote. “It is a drug habit under the guise of religion.”

When the Oklahoma territorial legislature proposed banning peyote, Quanah led a delegation of chiefs in opposition. He told the lawmakers that peyote use was healthy and helped some Indians quit drinking. “My Indians use what they call pectus; some call it mescal. All my Indian people use that for medicine … It is no poison and we want to keep that medicine. I use that and I use the white doctor’s medicine, and my people use it too … My ways in time will wear out, and in time this medicine will wear out too.

“… I do not think this Legislature should interfere with a man’s religion,” he concluded. The lawmakers agreed: the bill failed.

QUANAH SELDOM GAVE INTERVIEWS: early on he seemed to grasp the danger of speaking freely to white people. But in 1901 he sat down with an anonymous correspondent from the Oklahoman newspaper. The reporter was clearly fixated on the number of Quanah’s wives. He noted that each wife had her own bedroom and sewing machine, and that they took turns attending Quanah in the master bedroom. The reporter could not conceal his surprise to learn that a former Comanche nomad kept carpets on the floors, as well as bureaus, chiffoniers, lamps, and other articles of furniture.

The article reported that Quanah had many enemies among Comanches who spread rumors about him. “Some of the old people among the Comanches do not like me,” he acknowledged to the man from the Oklahoman. “They call me a white man. They are like all old people … They want to do now what they did fifty years ago. That’s no good anymore.”

Quanah dressed in traditional garb that day: a white eagle feather in his hair, his scalp painted yellow and parted in the middle, his long hair braided and wrapped in rich beaver skin on both sides of his head. He wore a colorful blanket around his waist, a standing linen collar, and a heavy silk tie fastened to the collar with a sunburst amethyst pin. But when the reporter asked to take his photo, Quanah asked if he could first change into modern clothes.

As the generation that had experienced the Comanche wars began to die off and the wars themselves became enshrined in myth, Quanah became a familiar figure at state fairs, rodeos, and parades, where he and his former warriors would stage “raids” and entertain the same whites whose parents they had once terrorized. A new Texas town near the Oklahoma border, just a few miles north of the site of the Pease River massacre, was named for him, as was the local railroad line. Quanah gave his namesake town his blessing: “May the Great Spirit smile on your town; may the rains fall in season; and under the warmth of the sunshine after the rain may the earth yield bountifully; may peace and contentment be with you and your children forever.”

He returned to Quanah, Texas, a few years later to attend Fourth of July celebrations, along with 225 braves, women, and children; they rode in the parade and he gave a speech. “I am not a bad man and have not done many of the things told about me,” he told the crowd. “My mother raised me like your mothers raised their children, but my father taught me to be brave and learn to fight to become chief of my people. But we want to fight no more.”

Even old enemies became allies. Sul Ross, the former Texas Ranger captain who had helped recapture Cynthia Ann at the Pease River, became a benefactor. Ross was elected governor of Texas in 1886 and re-elected two years later in part because of his reputation as the legendary Indian fighter who had rescued Cynthia Ann Parker. When Ross saw the advertisement for a photo of Cynthia Ann that Quanah had placed in the Fort Worth Gazette, he sent Quanah a copy of the daguerreotype of her nursing Prairie Flower that she had reluctantly posed for at A. F. Corning’s studio in Fort Worth in 1861. Quanah framed the picture, struck it on an easel, placed it in his parlor, and posed for photos sitting next to it.

By this time a new generation of Texas historians had rediscovered the Parker saga. John Henry Brown had first met Cynthia Ann in Austin in 1861 when her uncle Isaac brought her to the secessionist legislative session seeking an annuity for her and Prairie Flower, and his wife had helped dress her and escorted her to the gallery during the session. Brown, a former Texas Ranger, state legislator, newspaper publisher, and collector of pioneer tales, later wrote a brief history of the Parker family after being asked to introduce Isaac at a political gathering in Dallas in 1874. And he later recounted the tale of Parker’s Fort in his 762-page magnum opus, Indian Wars and Pioneers of Texas, originally published in 1880. Brown, who by then was mayor of Dallas, wrote that Ross had killed a warrior named Mohee, “chief of the band,” at the Pease River.

Quanah Parker in his bedroom with the photograph of his mother, Cynthia Ann, and sister, Prairie Flower, a photo sent to him by Texas governor Sul Ross.

Next came James T. DeShields, a twenty-three-year-old book salesman and amateur historian who contacted and collected material from Brown, Ross, Ross’s newspaper friend Victor M. Rose, Quanah, and Quanah’s cousin Ben Parker, and put together the first detailed account of the massacre, the fate of Cynthia Ann, and the emergence of her surviving child. Cynthia Ann Parker: The Story of Her Capture, first published in 1886, became the definitive version of her life. DeShields put the declaration “Truth is Stranger than Fiction” on the title page and dedicated the book to Ross.

DeShields promised his readers a “narrative of plain, unvarnished facts,” but he could not resist fanciful details and commentary. He claimed the Indian attack on Fort Parker involved five hundred warriors who, despite their vast numbers, used treachery against the worthy pioneers, making “such pleas with all the servile sycophancy of a slave, like the Italian who embraces his victim ere plunging the poniard into his heart.”

The young self-styled historian also used his imagination to portray Cynthia Ann’s “budding charms” as the white captive of dark-skinned savages.

“Doubtless the heart of more than one warrior was pierced by the Ulyssean darts from her laughing eyes, or charmed by the silvery ripple of her joyous laughter,” he wrote. No doubt she had fallen in love with Peta Nocona, “performing for her imperious lord all the slavish offices which savageism and Indian custom assigns as the duty of a wife. She bore him children and we are assured loved him with a species of fierce passion and wifely devotion.”

DeShields even claimed that Cynthia Ann rode alongside Peta Nocona and five hundred Comanches who sought to rescue the warriors trapped by Rip Ford’s raiders in Indian Territory in 1858. “Doubtless,” DeShields quotes Victor Rose, “Cynthia Ann rode from this ill-starred field with her infant daughter pressed to her bosom and her sons … at her side.”

By now a politician aspiring for the governor’s mansion, Ross assured DeShields that “my early life was one of constant danger from [Indian] forays.” He changed the identity of the warrior he killed at the Pease River from the little-known Mohee to “the chief of the party, Peta Nocona, a noted warrior of great repute.”

“It was a short but desperate conflict,” wrote DeShields of Ross’s clash with the Comanche chief. “Victory trembled in the balance … The two chiefs engaged in a personal encounter, which must result in the death of one or the other. Peta Nocona fell, and his last sigh was taken up in mournful wailings on the wings of defeat.”

Victor Rose, who served as Ross’s campaign strategist and biographer, undoubtedly had a hand in the rewrite. DeShields helped the campaign by transforming a brief, tawdry massacre into a heroic triumph: “the great Comanche confederacy was forever broken.” He also stated as fact I. D. Parker’s claim that Cynthia Ann and Prairie Flower, “her little barbarian,” had died in 1864.

Despite its many inaccuracies, DeShields’s account became enshrined in one of the most enduring of the Indian war histories, Indian Depredations in Texas, published in 1889. John Wesley Wilbarger’s 691-page book is an exhaustive compendium of Indian attacks on pioneers and their families, most of them drawn from firsthand accounts and previously published stories. He reprinted DeShields’s version of events without fact-checking a single sentence. The book helped establish DeShields’s work as the accepted official account of the Cynthia Ann saga, handed down through the generations and incorporated into the state of Texas’s public school history curriculum.

Brown, DeShields, and Wilbarger all depicted Comanches as savage killers shorn of all humanity—“these wild Ishmaelites of the prairie,” in DeShields’s words. Wilbarger was especially scornful of “maudlin, sentimental writers” who failed to recognize the brutality of the Indians. Such writers, he surmised, “never had their fathers, mothers, brothers, or sisters butchered by them in cold blood; never had their little sons and daughters carried away by them into captivity, to be brought up as savages … and certainly they never themselves had their own limbs beaten, bruised, burnt, and tortured with fiendish ingenuity by ‘ye gentle savages,’ nor their scalps ruthlessly torn from their bleeding heads.”

His own view of the Indian, said Wilbarger, was: “We are glad he is gone, and that there are no Indians now in Texas except ‘good ones,’ who are as dead as Julius Caesar.”

At the same time, each author praised Quanah, and their books contributed to his growing celebrity as the Noble Savage. Brown’s book includes a photo of Quanah and describes him as “a popular and trustworthy chief of the Comanches … a fine looking and dignified son of the plains.”

Each of these male authors created and buffed the macho frontier legend using whatever facts fit their vision and discarding those that were less convenient. But occasionally someone came along who gathered a more modest, fact-based account.

John Henry Brown’s daughter Marion spent three months at Fort Sill beginning in November 1886. Marion was a vivacious and unmarried twenty-nine-year-old seeking to restore her health in the dry climes of central Oklahoma, and she spent a lot of her time at parties, playing whist with the officer’s wives, and attending “hops” on the arms of various young officers. But her father had another mission in mind for her. “I sent you plenty of paper, pens, etc. and hope you will go into the Fort Sill history with a will to succeed,” he wrote in a letter addressed to “Dear Baby” just before Christmas. “The main point is to get the facts in clear shape.”

After the Christmas holidays ended, Marion Brown set out to do just that. She was introduced to Quanah through the old scout Horace Jones. In letters home, Marion expressed her surprise at hearing from both Jones and Quanah that Sul Ross had not killed Peta Nocona at the Pease River. Jones complained that Ross was getting too much glory for the massacre. Marion wrote of Jones, “I think him an old —— but everyone here seems to consider him reliable in all Indian history … I can scarcely understand anything he says, everything ends in a grunt.”

Still, Jones provided Marion with her most important evidence that Peta Nocona had survived the Pease River massacre. He told her that Nocona, hearing that Jones had seen and talked with Cynthia Ann after her recapture by the Texas Rangers, had sought him out at Fort Cobb, one of the northern stockades, where Jones was working as an interpreter after the army abandoned the ruined Camp Cooper. The two men sat out in the yard at Fort Cobb under a large walnut tree. Before they spoke, Nocona rubbed his hands in the dust, then on his chest, took out a pipe, lit it, and took a few puffs before passing it to Jones. “Now I want to hear the truth,” he declared.

Jones told him of Cynthia Ann’s capture and how she had been taken to her uncle’s house to live. Jones in turn asked Nocona about his two sons. His answer was suitably elusive. “They are way out on the prairie where you cannot see them,” Nocona replied, “but some day you may.”

Jones reckoned that the meeting took place in either the fall of 1861 or 1862. He never saw Peta Nocona again, but later heard that Nocona had lived several more years.

Marion avidly reported the details to her parents. She rather savored the prospect of discomfiting the newly elected governor of Texas. “What will Sul Ross say about Puttack Nocona?” Marion wrote. “I rather enjoy it myself. It will surprise people.” Indeed, it might have, but Marion Brown’s account was not published until 1970. Her father, perhaps for political reasons, made no attempt to print her story, although he ambiguously altered his own Indian Wars and Pioneers of Texas in its 1896 edition. In the section “The Fall of Parker’s Fort,” he credits Ross with killing “Mohee, chief of the band.” But in his portrait of Ross some 250 pages later, he writes that Ross “killed Peta Nocona, the last of the great Comanche chieftains.”

Marion was charmed by Quanah, but not taken in. The man she described was very much a performer. She noticed upon shaking hands that “his were softer than mine. He had his hair arranged in the Indian style, with an eagle feather standing up straight from his head, his face was painted, moccasins adorned his feet, the blanket was thrown carelessly around him and the remainder of his costume was strictly Indian with the exception of a neat pair of driving gloves.” He was so quiet and expressionless during their first meeting that Marion assumed he could not speak English. Then, after she told him she wanted to see him dressed as an Indian, he smiled widely, laughed, and replied, “No like to come this way. Come another time when can stay longer.” When one of her gentlemen friends called on her later that evening, he noted that Quanah already had five wives. “He asked if Quanah had asked me to be number six.”

Like any effective leader, Quanah intuitively grasped the importance of a clean public image. He was careful not to discuss the things he had seen and done as a warrior, and he discouraged other Comanches from talking about the past. He knew the state of Texas was conducting “depredation courts,” where residents could make claims for damages for destruction of property and loss of life and limb during the Indian wars. He feared such proceedings could evolve into criminal trials.

Quanah knew that Sul Ross’s claim that he had killed Peta Nocona at the Pease River was a falsehood, that his father had not been present during the battle, but despite what he said privately to Marion Brown, he refused to publicly contradict Ross. “Out of respect to the family of General Ross, do not deny that he killed Peta Nocona,” he wrote to his daughter Neda, who served for a time as Quanah’s personal secretary. “If he felt that it was any credit to him to have killed my father, let his people continue to believe that he did so.”

BY THE EARLY 1890S, Quanah was at the pinnacle of his success. His holdings consisted of a farm of 150 acres, 425 cattle, 200 hogs, 160 horses, 3 wagons, a buggy, and the newly completed Star House. He also controlled 44,000 acres of Big Pasture, thousands of which he privately leased to his rancher partners. He was presiding judge of the Court of Indian Offenses. He had outsmarted and outmaneuvered his opponents, white and red. He possessed the title of Chief of the Comanches while keeping his peyote faith and his polygamous family intact. No Native American in the United States enjoyed the same level of respect and admiration. None was as welcome in the white world. Even the Parkers were beginning to embrace him as an exotic but useful member of their extended family.

But at that very moment, it all began to unravel. And at the heart of the matter, as was so often true in relations between whites and Native Americans, was land.