Supper is over and a bloodred sun is setting outside the ranch house. Henry Edwards is taking a last look around the extended yard before dark, cradling his light shotgun, but it’s not game fowl he’s seeking. He fears the worst—that somewhere beyond the faint roll of the prairie, just out of sight, a Comanche raiding party is preparing to attack.

The year is 1869 and the Edwards family lives at the sharp edge of pioneer country, “holding the back door of Texas” in the northwest corner of the state. Comanches and Kiowas are punishing the range, killing and burning out settlers, making a mockery of the so-called peace policy that President Grant and the Quakers serving as his Indian agents are seeking to establish on the High Plains. Despite a series of massacres, a few pioneer families are staying put, trusting that their luck will hold, but Henry Edwards’s luck has run out. The night before, he sent off his brother Amos and his adopted son Martin to help a posse hunt down purported cattle thieves who had struck a neighbor’s herd. But now it’s clear that the thievery was just a ruse by Indians whose real goal is a murder raid. Having tricked their pursuers into a wild-goose chase, the killers are about to strike.

So begins The Searchers, Alan LeMay’s thirteenth novel, one of the most memorable Westerns of the 1950s. It is the story of two men, Amos Edwards and his adopted nephew, Martin Pauley, and their epic search for Amos’s niece Debbie, the sole survivor of the raid on the Edwards’s ranch house that LeMay so dramatically sets up in his opening chapter. Set in post–Civil War Texas, The Searchers is an odyssey through the last years of the Comanche-Texan wars, told from Martin’s point of view. It captures the magnificent heroism and endurance of the settlers who carried on in the face of overwhelming odds, but it also reflects their deep racial hatred of Comanches, who are portrayed as savage murderers and rapists true only to their own barbaric code. Harrowing, grim, and unrelenting, the book reflects LeMay’s abiding verdict that life is inescapably tragic and even the dead do not rest in peace.

The Searchers is an inverted captivity narrative. It focuses not on the victims nor on their Indian captors but rather on the pursuers, Amos and Martin, who embark upon a quest to rescue the captives and take vengeance on those responsible. Debbie, the object of their search, is nine years old when the story begins—the same age as Cynthia Ann Parker when she was abducted.

Alan LeMay was intrigued by the fact that James Parker, Cynthia Ann’s uncle, was a backwoodsman of dubious reputation and an unrepentant Indian hater. The novelist proceeded to build his own fictional character, Amos Edwards, from the bare bones of James’s life and quest. He created a second fictional searcher in Martin Pauley, whose own family had been slaughtered by Comanches when he was a baby. And LeMay updated the tale: instead of taking place in 1836, the raid and abduction occur after the end of the Civil War, which allowed LeMay to turn Amos into a disgruntled Confederate war veteran and to track the decline and final defeat of the Comanches by the U.S. Army as he tells the saga of Amos and Martin’s search for a fictionalized version of Cynthia Ann.

A meticulous researcher, LeMay collected information on sixty-four Indian abductions, including Cynthia Ann’s; his notes show references both to her and to her Comanche son Quanah. He compiled ten pages of typed and handwritten notes about abductions, battles, and Comanche bands. In the end he freely cherry-picked and mashed together features from several true stories to create his fictional one.

Amos Edwards is forty, “a big burly figure on a strong but speedless horse,” with heavy reddish brown hair and a short, silent fuse. “He was liable to be pulled back into his shell between rare outbursts of temper.” He is a drifter on the frontier: his résumé includes two years as a Texas Ranger, four years in the Confederate cavalry, and two long cattle drives working as a cowhand up the Chisholm Trail. Yet he always finds his way back home to work for his younger brother Henry on the ranch, and no one can quite figure out why. Amos’s secret is that he is in love with Martha, Henry’s wife. Amos tells no one; not even Martha suspects the truth.

Martin Pauley, his fellow searcher, is “a quiet boy, dark as an Indian except for his light eyes; he never did feel he cut much of a figure among the blond and easy-laughing people with whom he was raised.” Martin’s parents had settled the territory alongside two other families, the Mathisons and Edwardses, two decades earlier. Martin was a baby when his family was wiped out in a Comanche murder raid in the early 1850s. Henry Edwards found him lying under a bush where his parents hid him from the warriors, and Henry and Martha took him in and raised him as one of their own.

LeMay’s Texas frontier is a frightening place where families risk annihilation at the hands of savages, and those who remain do so because they feel they have no choice. It is a land where only the strongest and most stubborn seek to hold on. “It was Martha who would not quit,” writes LeMay, “and she had a will that could jump and blaze like a grass fire. How do you take a woman back to the poverty of the cotton rows against her will? They stayed.”

Martha’s insistence that she and her family remain on the frontier eventually leads to their destruction. No one blames her, however. It is the land itself that is truly at fault. “This is a rough country,” Amos tells Martin. “It’s a country knows how to scour a human man right off the face of itself. A Texan is nothing but a human man way out on a limb. This year, and next year, and maybe for a hundred more. But I don’t think it’ll be forever. Some day this country will be a fine good place to be. Maybe it needs our bones in the ground before that time can come.”

When the posse figures out they’ve been duped by the Comanches, Amos and Martin race back to the Edwards homestead to find the butchered corpses of Henry, Martha, and their two young sons. The Comanche raiders have abducted Debbie and her older sister, Lucy. The pioneers hastily bury the victims, and Amos, Martin, and five neighbors set out to try to find and rescue the girls. James Parker took weeks to get a posse going, while Amos and Martin are able to launch theirs at once.

They track the raiding party for five days, then realize that the Comanches have sucked them into an ambush. The Texans hold off a large force of Comanches in a gun battle at the Cat-Tails marsh, after which Amos, Martin, and Brad Mathison, Lucy’s ardent young suitor, continue the search alone.

Amos breaks off at one point to follow tracks up a narrow canyon, then catches up to the others minus a saddle blanket. Brad scouts ahead, finds the Indian camp, and reports back that he has spotted Lucy there. But Amos tells him that what he saw was a Comanche buck wearing Lucy’s dress. Amos found Lucy’s body the day before and buried her in his blanket. When Brad asks, “Did they—was she?” Amos explodes: “Shut up! Never ask me what more I seen!”

Despite the attempts of the others to stop him, a crazed Brad charges into the Comanche camp on his own and is killed and mutilated. Amos and Martin continue their pursuit for several more weeks, but break it off as winter closes in. “This don’t change anything,” Amos pledges. “If she’s alive, she’s safe by now, and they’ve kept her to raise … We’ll find them in the end; I promise you that … We’ll catch up to ’em, just as sure as the turning of the earth!”

The two men strike out for Indian Territory, just as James Parker did in real life. But after months of false leads and endless frustration, they return to the Mathison homestead. Amos is determined to continue the search on his own. Young Laurie Mathison loves Martin and begs him to stay behind, telling him that Amos will find Debbie without his help. “That’s what scares me, Laurie,” he replies. “I’ve seen all the fires of hell come up in his eyes when he so much as thinks about getting a Comanche in his sights.” Martin fears for Debbie’s life. He knows Comanches often kill their white captives when under attack. “What I counted on, I hoped I’d be there to stop him, if such thing come.”

The tension is established that drives forward the rest of the narrative. Amos Edwards is an angry, implacable man bent upon revenge. Even though Debbie is the daughter of Martha, the only woman he has ever loved, Amos doesn’t care if she lives or dies. His goal is to avenge Martha’s rape and murder, and to destroy the world of those who have destroyed his. His sole motivation is hate.

When it comes to Comanches, Martin is no less hateful. He embraces the Texan idea of a war of extermination. “I see now why the Comanches murder our women when they raid—brain our babies even,” he tells a fellow pioneer. “… It’s so we won’t breed. They want us off the earth. I understand that, because that’s what I want for them. I want them dead. All of them. I want them cleaned off the face of the world.”

But Martin’s hatred has its limits. It extends to all Comanches, but not to Debbie, even if she has grown up to become one of them. Martin values kinship above all else. Because Debbie is his sister, his obligation to her is clear, unbreakable, and nonnegotiable. While the world around him seems crazed with bloodlust and vengeance, his own moral compass remains firm.

The Searchers is a journey of discovery. Martin Pauley grows from a terrified, callow teenager into an adept, experienced, and grimly determined tracker and huntsman. His convictions harden and his willingness to challenge his elders—and most specifically Amos Edwards—evolves into a moral certainty. Even Amos comes to recognize Martin’s willingness to go all the way to defend Debbie. “I believe you’d do it,” he tells Martin, with grudging admiration. “I believe you’d kill me in the bat of an eye if it comes to that.”

Their search goes on for five years, echoing incidents that occurred in James Parker’s hunt for Cynthia Ann. Just as James received unreliable information from several traders in Indian Territory, so, too, must LeMay’s searchers deal with the machinations of an unscrupulous trading post owner. And just as James and a companion had to shoot their way out of an Indian ambush, so must Amos and Martin escape several attacks.

But their main antagonist is the land itself, the relentless High Plains of North Texas and the Panhandle, the flat, endless, natural habitat of the Comanches and a place where white men can expect to find death or a kind of malevolent, spirit-sucking black magic. “That country seemed to have some kind of weird spell upon it,” writes LeMay, “so that you could travel in one spot all day long, and never gain a mile … If a man could have seen the vastness in which he was a speck, the heart would have gone out of him; and if his horse could have seen it, the animal would have died.”

There are times when nature seems to want to kill Amos and Martin even more than the Comanches do. They are trapped by a sudden blizzard that takes them by surprise, blinds them in its white fury, and buries them alive. The storm is like a murderous animal: “It tore at them, snatching their breaths from their mouths, and its gusts buffeted their backs as solidly as thrown sacks of grain.” It renders them “sightless and deafened in the howling chaos,” and it plunges them down a twelve-foot gulley, breaking the neck of Amos’s pony. They shelter under a newly downed willow, dig a small bare spot for a fire, and spend sixty hours huddled over it, taking turns staying awake to keep from drifting into a frozen death. Finally, they emerge from their snowbound prison, their lips cracked and blackened, their beards frostbitten, and trek 110 miles to the fragile safety of Fort Sill.

They finally locate Debbie living in the encampment of a Comanche chief named Scar. They arrive claiming to be traders, but Scar knows who they really are. They keep their cool and ride off, but Debbie intercepts them outside the village and warns them to flee, that Scar is planning to kill them. She refuses to go with them: she is betrothed to a young warrior and considers the Comanches her people, even though Martin tries to explain that it was Scar who led the raid that killed her family—just as Cynthia Ann’s Comanche husband, Peta Nocona, had led the murder raid on Parker’s Fort in 1836. The scene mirrors that of Cynthia Ann when white scouts came across her in 1846 but she refused to consider leaving the Comanches to return to her Texas family.

In the novel, Amos and Martin meet up with a contingent of Texas Rangers, U.S. Cavalry, and their Tonkawa Indian allies who aim to attack Scar’s encampment. Martin also runs into Charlie MacCorry, a local cowhand and Texas Ranger, who informs Martin that he and Laurie have gotten married.

The Texans and soldiers attack Scar’s village and overcome the defenders—not unlike the Ranger attack at the Pease River in 1860. Amos sees a Comanche girl who looks like Debbie, reaches for his pistol, but at the last minute chooses to rescue her. But it isn’t Debbie. The girl pulls a gun from the fold of her outfit and shoots him dead.

Martin searches in vain for Debbie among the wreckage of the village, then trails her to the remote northwest, where he finds her cold, exhausted, and dying of thirst and cold. He warms her body with his own and keeps her alive. She tells him that she ran away from Scar and the Comanches after discovering that what Amos and Martin had said was true: the Indians had killed her family. Now she has no family, no people, and no hope. “I have no place,” she tells him. “It is empty. Nobody is there.”

Martin promises he will stay with her. “I’ll be there, Debbie.”

He begs her to remember the past. “I remember,” she tells him. “I remember it all. But you the most. I remember how hard I loved you.”

Love and memory have the last word. But there is no way to know how these two orphans will fare in such a merciless land. Martin’s possibility of happiness with Laurie has been shattered, while Debbie has lost her home and her people. Their only hope now is each other.

The Searchers is a story of courage and endurance, of people who refuse to give up even when the odds are ruthlessly stacked against them. But it is a hard, pessimistic book, as unyielding as the landscape it takes places in. In its sense of despair, its emotions echo those of Cynthia Ann Parker after she was purportedly liberated in 1860.

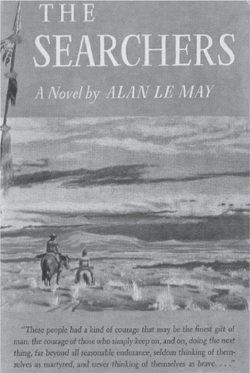

Alan LeMay dedicated the book to his Kansas ancestors. The book jacket, adapted from a letter Alan wrote his publisher in July 1954, explains: “These people had a kind of courage that may be the finest gift of man: the courage of those who simply keep on, doing the next thing, far beyond all reasonable endurance, seldom thinking of themselves as martyred, and never thinking of themselves as brave.”

In this hard land, the most destructive force is the Comanches themselves. Unlike in Painted Ponies, LeMay’s first novel, there are no Noble Savages in The Searchers and not one sympathetic or admirable Indian character. The Comanches are brutal, duplicitous, and merciless. They ruthlessly take advantage of the U.S. government’s naïve peace policy to shelter during the winter in government reservations in Indian territory, then resume raiding and pillaging vulnerable pioneer families in Texas in springtime. They literally spit upon and try to intimidate the benevolent Indian agents who seek to help them. They are unstoppable, unappeasable, and fundamentally inhuman. All of their actions and instincts are unpredictable and confounding. “I ain’t larned but one thing about an Indian,” says Amos. “Whatever you know you’d do in his place—he ain’t going to do that.”

Even the gift of language—one of the fundamental attributes of humankind—seems beyond them. “The Comanches themselves seemed unable, or perhaps unwilling, to explain themselves any more exactly,” writes LeMay. “… Nothing else existed but various kinds of enemies which The People had to get rid of. They were working on it now.”

The idealistic young novelist who wrote so sympathetically about the Cheyenne Indians in Painted Ponies twenty-five years earlier had hardened into the remorseless creator of The Searchers. Alan himself explained his antipathy to the Comanches as his attempt to even up the literary box score. “A great deal has been written about historic injustices to the Indian,” he wrote one reader. “I myself once wrote a book highly partisan to the Northern Cheyennes. I thought it was time somebody showed that in the case of the Texans, at least, there were two sides to it, and that the settlers had understandable reasons to be sore.”

But the real depths of LeMay’s hard-earned pessimism are evident in his portrayal of Laurie Mathison, Martin’s lost love. In most of LeMay’s novels and screenplays, the hero gets the girl, and vice versa. Not so in The Searchers. Martin loses Laurie for the noble reason that he won’t abandon his sacred mission for the sake of their personal happiness. Laurie tries to be as virtuous as he is; she waits patiently for years and helps him however she can. But in the end she surrenders to despair and marries Charlie MacCorry. Before she does so, she endorses the idea of an honor killing—that because Debbie has been defiled by savages, she must be killed to restore her own purity and her family’s honor. Debbie has “had time to be with half the Comanche bucks in creation by now,” Laurie tells Martin. “… Sold time and again to the highest bidder … got savage brats of her own, most like.”

“Do you know what Amos will do if he finds Deborah Edwards?” she adds. “It will be a right thing, a good thing—and I tell you Martha would want it now. He’ll put a bullet in her brain.”

As she speaks these hateful words, Laurie’s beautiful face hardens, and “the eyes were lighted with the same fires of war [Martin] had seen in Amos’ eyes the times he had stomped Comanche scalps into the dirt.”

Martin refuses to accept Debbie’s death as a just solution. “Only if I’m dead,” he tells Laurie, and leaves her behind one last time in order to rescue his adopted sister. For Martin, kinship is stronger than love or hate.

The Searchers was Alan’s first serious literary effort in ten years, and it was a painful and painstaking labor that took him nearly eighteen months to write. “In all I wrote about 2,000 pages, mostly no good, to get the 200 pages we used,” he told one letter writer.

When another letter writer suggested he write a novel about Cynthia Ann Parker, Alan replied with a gentle refusal. The Searchers, he wrote, “represents about all I have to contribute on this particular subject.” It was as close as Alan LeMay would come to acknowledging the connection between Cynthia Ann’s story and his novel.

Alan first wrote the novel in five serialized pieces, titled “The Avenging Texans,” which his New York agent, Max Wilkinson, sold to the Saturday Evening Post for an undisclosed sum. Next, Wilkinson took it around to book publishers. He and Alan settled on Harper & Row and an experienced and empathetic editor named Evan Thomas, who would later become famous for editing John F. Kennedy’s Profiles in Courage and William Manchester’s The Death of a President.

In the end The Searchers can be read not just as Alan LeMay’s tribute to his ancestors and his purest and most personal expression of the American Western founding myth, but also as an exploration of his own hardened psyche. LeMay felt he had barely survived Hollywood, hanging on to a piece of his soul in a predatory environment where only the strongest and most cunning could survive. He himself had become a searcher for his own autonomous place in a difficult world. His kinship with his hardy ancestors was not just a blood tie but a link forged by grim experience. In this sense—as with all storytellers—Alan’s story is about himself.

The book was a critical success. “Its simplicity is one of subtle art,” wrote the literary critic Orville Prescott in the New York Times, “suggestive, charged with emotion and the feel of the land and the time.”

The Searchers, by Alan LeMay, published in 1954 by Harper & Brothers.

The hardcover book sold more than fourteen thousand copies, and has continued to sell in various reprints and paperback editions for more than a half century. It garnered a lot of gratifying attention, which Evan Thomas eagerly reported back to his author. “One of the White House correspondents tells me that Eisenhower is reading the book, with great pleasure,” Thomas wrote to Alan in February 1955.

Reader’s Digest bought the rights for $50,000, half of which went to Alan and half to Harper. But the most important sale was to Cornelius Vanderbilt Whitney, a playboy businessman and heir to the immense Vanderbilt-Whitney fortune. Whitney had just formed a film company and hired Merian C. Cooper as his executive producer. Cooper’s other business partner was the famed film director John Ford.

Alan returned home to Pacific Palisades from two weeks of researching his next novel among the Kiowas in Oklahoma to learn the good news that H. N. Swanson, the legendary Hollywood literary agent who once boasted F. Scott Fitzgerald as a client, had sold the movie rights to C. V. Whitney Productions for $60,000. The amount, “I am told (not too reliably), ties the record for the year,” an ecstatic LeMay wrote to Thomas, “the whole thing being made possible by the rewrite under your coaching.”

Still, despite his years of experience as a screenwriter—or more likely because of them—Alan wanted to have nothing to do with the movie. He told his son Dan that he had sold the rights with the stipulation that he would not have to write the screenplay or even see the film. Having survived working for Cecil B. DeMille for a half-dozen years, the last thing LeMay wanted was to get involved in making a movie with John Ford, who was by reputation another famous tyrant and scourge of screenwriters. LeMay had been in Hollywood long enough to know how Ford liked to work. He would probably use his own in-house screenwriter, Frank Nugent, and film the picture in Ford’s personal Western playground: Monument Valley, the stunningly beautiful Navajo tribal park on the Arizona-Utah border. It was a ridiculous notion to film a story set in the flat, high plains of Texas in the lunar mesa dreamscape of Monument Valley. But when it came to making Westerns, nobody, especially a lowly novelist and screenwriter, could tell John Ford what to do. Better, thought Alan LeMay, to get out of the way.