As John Ford liked to point out, movies and Westerns grew up together, a natural marriage of medium and genre. The first moving picture in the United States was a series of still photographs in 1878 of a horse racing down a track south of San Francisco on the grounds of what became Stanford University, stitched together by Eadweard Muybridge to prove that horses did indeed gallop with all four feet off the ground. From that time on, horses and pictures seemed to go together, as Ford himself once noted: “A running horse remains one of the finest subjects for a movie camera.”

The official end of the American Frontier, solemnly announced like a death in the family in 1890 by the Office of the Census, virtually coincided with the birth of motion pictures. Frederick Jackson Turner’s frontier thesis—that the West had provided a safety valve that had defused social tensions and class conflict during the American nation’s adolescence—became a template for the Western film, which was from its beginnings a form of elegy for a time and place that had already vanished.

After The Great Train Robbery in 1903, the genre slowly took shape over the course of a decade, overlapping with genuine remnants of the past. Ford himself befriended the legendary lawman and gunslinger Wyatt Earp, who spent his final years loitering around Hollywood film sets. Buffalo Bill Cody, Frank James, the surviving Younger brothers, the former Comanche captive Herman Lehmann—all appeared in various cinematic accounts of their life and times, adding a dab of color, showmanship, and faux authenticity.

The first moving pictures of Indians were likely made by Thomas Edison in 1894 for a small kinetoscope called Sioux Ghost Dance, an immediate hit on the penny arcade circuit. The early films were makeshift and improvisatory. They used real locations and real Indians. One of the first was a short called The Bank Robbery, filmed in 1908 in Cache, Oklahoma, in the heart of the former Comanche reservation by the Oklahoma Mutoscope Company. One of its stars was the former Comanche warrior turned peace chief, Quanah Parker. After outlaws rob the bank at Cache, Quanah rides with the posse that tracks them to their hideout in the Wichita Mountains. Quanah is involved in a shootout in which all of the robbers are either gunned down or captured. The money is restored to the bank and the outlaws are hauled off to jail. Despite his Comanche ethnicity, Quanah Parker is undifferentiated from the rest of the volunteer lawmen—just a good citizen doing his duty.

But that notion of the Indian as ordinary community member was quickly supplanted. As the Western film and its storytelling evolved, it quickly adopted a fixed set of ideas and images about Native Americans from nineteenth-century literature, theater, and legend. There were two dominant stereotypes. The first was the Noble Savage: the Indian who appreciated the benefits of the white man’s civilization, wished to live in peace, and was often more heroic and moral than the craven whites he had to contend with. This was the role Quanah Parker had sought to play after his surrender in 1875, both to protect his people and to enhance his own stature.

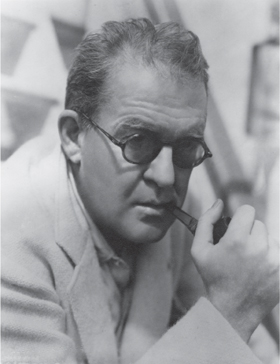

John Ford, ca. 1940.

In Hollywood’s first full-length feature film—Cecil B. DeMille’s The Squaw Man, made in 1914—an English nobleman journeys to the American West to create a new life for himself after taking the rap back home for a crime he didn’t commit. He falls in love with a beautiful Ute maiden who kills an evil rancher to save the nobleman’s life. They marry and have a child, but when a determined sheriff comes to arrest her for the killing six years later, the doomed maiden kills herself to protect her family and prevent an Indian war. The Squaw Man, which was remade several times over the next few decades, presents two enduring social lessons: consensual sex across racial lines is almost always fatal to the Indian participant; and the Noble Savage is far too noble to survive in the modern world ruled by whites.

Over time this stock figure was pushed aside by a frightening and dramatically more potent stereotype: the treacherous, untamable, sexually voracious Cruel Barbarian, abductor and murderer of white women and children, and obstacle to civilization. This Indian was a much better fit for the needs and imperatives of feature-length films. And just as Indian characters helped shape movies, so did movies help shape our modern image of the Indian. The old myths about Indians from frontier days were readily transferred to the new medium of film, writes Wilcomb E. Washburn, a cultural historian with the Smithsonian Institution, “because the characteristics that define American Indians are all dramatically conveyed by film. In violent, exotic and dramatic terms—savage, cruel, with special identity, villain, hero, worthy foe. Objects of fantasy and fable.”

One of the first films of D. W. Griffith, founding father of American cinema, was The Battle at Elderbush Gulch (1913), a twenty-nine minute short starring Mae Marsh and Lillian Gish, in which a band of drunken Indians launch a war against white settlers after a misunderstanding leads to the death of an Indian prince. The Indians kill a white woman and murder an infant by crushing its skull. Marsh’s character saves another white baby by racing onto a battlefield to take the infant from the arms of a dead settler and crawling back to safety. The Indians then besiege a small cabin of settlers and the end seems near; one man aims a gun at the head of Gish’s character to spare her the classic Fate Worse than Death of rape by savages. But the cavalry arrives in a nick of time to save the small band of settlers, mother, baby, waifs, and puppy dogs.

Almost from the moment he got off the train at Union Station in Los Angeles in 1914, the young John Ford worked in Westerns, first as a stuntman, cameraman, and actor. Tornado (1917), the first film he directed, was a Western, and he once estimated that perhaps one-fourth of his total output of movies were in the same genre. He groomed and cultivated Western film stars like Harry Carey, George O’Brien, Henry Fonda, and, of course, the greatest of them all, John Wayne. His entourage included wranglers, stuntmen, and Native Americans, and he eventually came upon Monument Valley, a remote and breathtakingly beautiful corner of Utah and Arizona, and used it as the setting for a half dozen of his finest films. His greatest silent movie, The Iron Horse (1924), was an epic Western, as was Stagecoach (1939), the film that revitalized the genre artistically and commercially after a decade of stagnation and helped make a star of Wayne. These films were rip-roaring adventure stories, with good guys and bad guys, Indian attacks and gunplay. But they were also fables about how America became great.

“A director can put his whole heart and soul into a picture with a great theme, for example, like the winning of the West,” he told one newspaper interviewer at the height of his silent-film career in 1925, and you can hear the enthusiasm spilling out from the page. Movies like The Iron Horse, he proclaimed, “display something besides entertainment; something which may be characterized as spirit, something ranking just a little bit higher than amusement.” The heights that film creators can achieve, he added, “are governed only by their own limitations.”

HE WAS BORN John Martin Feeney in February 1894 in Cape Elizabeth, Maine, of Irish immigrants, the tenth of eleven children, six of whom survived to adulthood, and he grew up in nearby Portland. As he built his myth about America, so, too, would he construct his own personal myth, beginning with his own name. He would claim to have been born Sean Aloysius O’Feeney—a more emphatically Irish name. It was the first of many small fictions. “When the legend becomes fact, print the legend,” a newspaper editor opines in The Man Who Shot Liberty Valance (1962), Ford’s last great Western. It could have served as his personal motto.

His brother Francis, twelve years his senior, left home early, changed his last name to Ford, and migrated to the newly hatched moving-picture business in Los Angeles as an actor and director. Francis acted in and helped direct some of the first Westerns, two-reelers such as War on the Plains (1912) and Custer’s Last Fight (1912) that early studio mogul Thomas Ince shot at a ranch in Santa Ynez Canyon overlooking Santa Monica. After graduating high school in 1914, John was rejected by the U.S. Naval Academy, then dropped out of the University of Maine after just a few days on campus. Before the year was out he joined his older brother in the new promised land of Southern California. Francis got him work: in one of his earliest roles he played a Ku Klux Klansman on horseback in D. W. Griffith’s The Birth of a Nation in 1915. Two years later Carl Laemmle, president of Universal Studios, decided that Ford had the self-assurance, commanding presence, and loud voice required to direct a film crew. The Tornado was a two-reel, thirty-minute Western, and Ford, who was a gangly, awkward, pasty-faced six-footer with little physical charisma, was both star and director. The former role was a flop; the latter proved to be his destiny.

Hollywood was bursting at its seams. Gone were the barley fields that Horace Henderson Wilcox, a real estate developer from Kansas, had first carved into imaginary avenues and boulevards in 1887. The construction in 1904 of a trolley car line from central Los Angeles seven miles to the east and the incorporation of the distant village into the city six years later brought cheap municipal water and sewage and the budding film industry, which found Hollywood’s open spaces and benign climate conducive to outdoor work. It was far easier logistically to film Westerns here than in the real West. Already the illusion was being spun.

Young John Ford arrived in Hollywood in time to watch pioneering filmmakers like Griffith and DeMille create the foundations of modern cinema, and he learned the craft from the bottom up. He saw quickly that Westerns would be his ticket to success. Soon after he started working at Universal, he teamed up with a dark-eyed actor from the Bronx with a long, soulful face. Harry Carey was a law school graduate, semi-pro baseball player, actor, and writer who had come out to Hollywood from Long Island City with Griffith’s Biograph company in 1913. Carey was sixteen years older than Ford and knew his way around film sets, ranches, and horses. The two men ground out a series of low-budget, twenty-five-minute two-reelers, then defied their bosses by making Straight Shooting, a full-length feature, without prior permission. Carey plays Cheyenne Harry, a hired gun who starts out working for a corrupt cattle boss but changes sides to support a beleaguered farmer. Carey’s character is deliberate, solemn, measured, and thoughtful. There are no wasted gestures or actorly flourishes. He wears an unadorned dark shirt, crumpled hat, and rolled-up denims. Ford admired Carey’s naturalistic style—as did a strapping teenager named Marion Morrison growing up in nearby Glendale who, after watching Carey’s films, began to adopt it as his own.

When Universal’s moneymen found out what Ford and Carey had done, they wanted to cut the film to two reels and fire both men. But Irving Thalberg, executive assistant to studio head Laemmle, intervened, and Straight Shooting became Ford and Carey’s first hit. The two men went on to make a total of twenty-three Westerns using classic dime-novel plots with titles like Three Mounted Men, The Phantom Riders, Hell Bent, and Roped. “They weren’t shoot-’em-ups, they were character stories,” Ford later recalled. “Carey was a great actor, and we didn’t dress him up like the cowboys you see on TV.”

The partnership eventually fell apart over money, jealousy, and competition for recognition—recurring themes in many of Ford’s wrecked friendships. But his work with Carey established Ford as a dependable action film director, and his career flourished. When his contract with Universal expired, he moved to Fox, a bigger and more respectable studio.

In 1920 he met and married a dark-haired Irish woman named Mary McBryde Smith, and they moved into an unassuming stucco house on Odin Street in the Majestic Heights section of Hollywood. They quickly had two children, Patrick, born in April 1921, and Barbara, in December 1922. Life seemed good. Ford worked steadily at Fox, grinding out feature-length Westerns according to a tried-and-true formula, including two films with cowboy star Tom Mix. By 1923 he was making almost $45,000 per year. But his restless ambition pushed him further. In 1924 he made The Iron Horse, an epic tale of the building of the first transcontinental railroad. It set the story of a young man’s quest for revenge for the murder of his father against the backdrop of a great historical event that celebrated national pride and manifest destiny.

Ford had found his future. The Iron Horse is pure entertainment, crammed with evocative compositions and action scenes, patriotic fervor and passionate hokum. It’s got buffalo herds, cattle drives, stampedes, drunken brawls, shootouts, crass humor, easy women, villainous businessmen, new towns springing out of the barren Plains, Buffalo Bill, and Abraham Lincoln. And it’s got Indians—brutal, treacherous, and picturesque symbols of a way of life being pushed inevitably toward extinction.

Early on in The Iron Horse there is a harrowing scene in which the leader of a band of Cheyenne Indians cruelly murders a white man with an axe while the man’s young son watches from hiding. Ford stretches the moment for maximum terror, crosscutting between the smiling, sadistic killer swinging the axe in his hand, the cowering soon-to-be victim, and the horrified young onlooker. After the killer strikes, he rips off his victim’s scalp and the frenzied Cheyenne celebrate with an orgy of dancing and elation. It is one of the ugliest moments in early American cinema and one that seems calculated to make Indians seem at once both fiendish and pathetic. Their leader turns out to be a renegade white man who goads his Indian followers into acts of barbarism and serves the will of a villainous white entrepreneur seeking to sabotage the railroad project. The Indians are obstacles to progress and they are doomed. Ford used hundreds of Sioux, Cheyennes, and Pawnees for The Iron Horse, most of them outfitted in their own native garb. They are a breathtaking sight careening down the warpath to attack the railroad construction crew. Still, whatever reverence or respect Ford would later hold for Native Americans, something more malign is on display in The Iron Horse.

After The Iron Horse, Ford continued to alternate studio potboilers and more ambitious works such as 3 Bad Men and Four Sons. By 1927 he had directed some sixty films, nearly three-quarters of them Westerns. He prided himself on his productivity and the iron control he wielded on his film sets. “When he walked on the set, he knew that he was God,” said director Andrew McLaglen, whose father Victor became one of Ford’s favorite actors.

Many silent film directors found it difficult to adjust to the new era of sound, which inevitably changed the character of visual setups and the nature of film acting. Ford was only thirty-three when The Jazz Singer premiered in October 1927, but some of the studio bosses considered him washed up. He had a few more small hits, but he was developing a reputation as a serious drinker and a difficult man to work with. When Fox loaned him out to the Goldwyn Company in 1931 to shoot the Sinclair Lewis novel Arrowsmith, Ford got into a creative dispute with Sam Goldwyn, stormed off the set, and later showed up for work “bruised and battered, spoke incoherently, and couldn’t remember what had been said minutes before,” according to a Goldwyn Company memo. Goldwyn not only fired Ford, he forced Fox to refund $4,100 of the money he had paid for Ford’s services.

John Ford needed a rescuer—and not for the first nor last time in his life, one appeared.

MERIAN CALDWELL COOPER COULD BOAST of the kind of dashing, daredevil biography that Ford envied and wished for himself. Born in Georgia of southern aristocrats who were long on pedigree but short on cash, Cooper dropped out of the Naval Academy during his senior year to join the Merchant Marine. He served as an aerial observer during World War One, was shot down in a dogfight when his plane caught fire, and wound up in a German prisoner-of-war hospital. After the war, he joined the Polish Air Force and fought against the Red Army. Shot down again, he escaped after a year in prison and was decorated by the president of Poland. After a brief spell as a newspaper reporter in New York, he set out to explore the world with a motion-picture camera. Working with Ernest B. Schoedsack, a newsreel cameraman, Cooper made his first film, Grass (1925), a documentary about the summer migration of Bakhtiari tribesmen. Two years later they made Chang (1927), about a family living in the jungle in northern Siam. And in 1929 the two men made their first Hollywood feature, The Four Feathers, one of the last great silent films, set in colonial India in the 1850s.

Affable, chatty, and impulsive, Cooper was a self-styled visionary and hard-charging self-promoter, a showman who claimed to have first paired Fred Astaire and Ginger Rogers, and an early pioneer of Technicolor, which he described with characteristic humility as “a panacea for all industrial ills.” He so hated to be unproductive that if he was reading a paperback book and had to go downtown on the subway, he would tear out enough pages to last him for the trip. He talked at a relentless machine-gun pace, spraying ideas and enthusiasm just like he sprayed tobacco leaves and ash from the pipe he was constantly relighting.

Cooper went to work for David O. Selznick at RKO Studios in 1931 as an executive producer. Two years later Cooper made King Kong, an iconic adventure film that expanded the imaginative possibilities of what movies could be. That same year he listened as Winfield Sheehan at MGM complained that John Ford was a washed-up hack who couldn’t get the feel of talking pictures and drank too much. “That’s too bad,” said Cooper, who happened to believe that Ford was one of Hollywood’s greatest talents. He proceeded to invite Ford to RKO for a meeting at which the director arrived “with a chip on his shoulder which I immediately put at ease.” The two men hit it off. Cooper told Ford he could make any picture he wanted, provided he also made a second one chosen by Cooper. With Cooper at his side, Ford drank a little less, at least while working, and tried a little harder to please the studio bosses. Over time Cooper became the middleman between Ford and the studio system, freeing the director to do some of his best work.

With Cooper’s help, Ford delivered The Lost Patrol (1934) and The Informer (1935). The latter was a major work—a dark drama of betrayal set in Dublin but filmed on an RKO soundstage in shadows and fog that reflected the style of the German Expressionists. It won Ford his first Academy Award for best director, plus Oscars for Best Actor (Victor McLaglen), Best Screenplay (Dudley Nichols), and Best Musical Score (Max Steiner).

Back at Fox, Ford answered to Darryl F. Zanuck, the autocratic executive producer who controlled virtually every part of the filmmaking process. Under Zanuck’s guidance, Ford directed popular stars like Shirley Temple and Will Rogers, making films set in small-town America that celebrated the values and sensibilities of a simpler world that was already fading from view, if it ever indeed existed. This period culminated in one of his most classic works, Young Mr. Lincoln (1939), his first picture starring Fonda. It was followed by a trio of films—The Grapes of Wrath (1940), The Long Voyage Home (1940), and How Green Was My Valley (1941)—that most truly define Ford as a film artist. The films are brilliantly composed and lovingly photographed, and each one comes to a melancholy conclusion about the meaning of life and the demands of family, friendship, and community. Tom Joad in The Grapes of Wrath must separate himself from his family and become a fugitive. Driscoll in Long Voyage surrenders his freedom while protecting his comrades and dies a martyr to the cause of friendship. The Morgan family in Valley disintegrates, as does its Welsh coal-mining village, in the face of economic and social forces beyond its control.

Ford nursed similarly painful passions in his own life. Even after he married Mary, he conducted a number of affairs with young actresses, the most intense of which was with Katharine Hepburn. As he grew older, his flirtations grew more and more pathetic—ostentatiously ogling young starlets and blurting out crude remarks. He also collected handsome young men, although here the sexual component was repressed. He nurtured his community of actors, stuntmen, and crew members whom he used in picture after picture—the John Ford Stock Company, as they informally dubbed themselves. It was his version of a rural Irish village, with himself as the stern but loving squireen. But when his mood turned dark, as it did at some point during nearly every picture he made, he could turn cruel and abusive, seeking easy targets for his wrath. “There was an essence of fear in every Ford camp,” said Frank Baker, a character actor who worked with him often in the early years. “He always picked on somebody at the beginning of a picture, and he’d let them have it … You couldn’t do anything right. And he just sat there with that flat voice, and he would attack you; he would humiliate you. He’d make you grovel.”

Ford’s father had been a saloon manager, and alcohol seemed embedded in the family DNA. Ford, his wife, Mary, and both his children, Patrick and Barbara, were all heavy drinkers. He pledged never to drink while working on a film. But when a project ended, he would let loose. “Daddy is what we called in those days a periodic,” Barbara recalled. “He would come to my mother and say ‘I filmed the picture, I’ve cut the picture, music is okayed … it’s shipped for negative, now call the bootlegger. And here is $1,000 for you to do what you want,’ and then he got drunk. And he drank for three weeks.” The reason? Barbara, who herself struggled with alcoholism all her life, knew the answer: “Escape. Oblivion, you know. He had done his job.”

As time went on, the drinking got worse. Mark Armistead, a Navy lieutenant commander on a PT boat who worked with Ford during World War Two, recalled that Ford would sometimes go on a bender for no particular reason. “One drink—he’s the type of person that one drink is one too many and a thousand is not enough.”

Armistead, who recalled his time with Ford with great warmth laced with despair, described him as an easily distracted man who always needed to be looked after, especially when he traveled. “The only thing he carried in his pocket was the rabbit’s foot, a handkerchief and a pocket knife, never any money … Never give him a baggage check because in thirty seconds he would lose it.”

He was, ultimately, a profoundly lonely man. Philip Dunne, one of his early screenwriters, told biographer Joseph McBride that Ford had no true friends. “They’d go on his yacht and drink and play cards, but there was a lack of intimacy,” said McBride. “I think Ford had serious problems with intimacy all his life.”

The luminous young actress Maureen O’Hara thought she had become friends with Ford when he cast her in How Green Was My Valley in one of her first starring roles. They bonded over their shared Irish heritage: O’Hara had been born in Dublin and could dish out the blarney with a vigor that delighted Ford. She loved the conviviality of his family dinner table, although she noticed early on that he could be casually insulting to Mary. O’Hara described Ford on the Valley film set as a combination of tyrant and magician, slouched in his director’s chair as if on a troubled throne. Although he was only forty-seven, he looked older and unhealthy to O’Hara. His “thick eyeglasses protruded from under the rim of a weather-beaten hat, and his rumpled clothes looked as though they never made it to the cleaners … Commanding and demanding, his dictatorial manner was matched only by the ease of his competence.”

To O’Hara, Ford was a visual master who painstakingly composed every frame. She recalled how in an early scene he had a kitchen chair placed so that its shadow was bigger than the actors. “I looked at its enormity, its imposing presence, and thought, My God, look what’s he’s doing. It’s magnificent.”

Over time O’Hara became close to Ford and his family. Then at a Christmas party at the Odin Street house, she let slip a casual remark that offended Ford—she could not even recall its content—and he leaned back and punched her in the jaw. “I felt my head snap back and heard the gasps of everyone there as each of them stared at me in disbelief and shock,” she recalled. No one said a word. She got up and silently left the house. The incident was never mentioned again. But it was one of several that convinced Maureen O’Hara that there was an ugly streak of anger lurking behind Pappy Ford’s front of benevolence. Ford, she concluded, “built walls of secrecy, lies, and aggression.”

A decade later, O’Hara would claim, she walked into Ford’s office without knocking one day and found him kissing a man—“one of the most famous leading men in the picture business.” O’Hara does not name the actor, although it’s likely from the context that she was referring to Tyrone Power, who was making The Long Gray Line with Ford at the time.

Harry Carey Jr., whom Ford often treated like a favorite nephew, experienced two sides of Uncle Jack. Ford could be a kind, gracious, and avuncular mentor. “I didn’t really feel I could act until I worked for John Ford,” said Carey. “I didn’t know I was capable of doing what he made me do.”

At the same time, Ford instinctively smelled out weakness and ambivalence and pounced upon those too vulnerable to fight back. Periodically on a film set he would order Carey to bend over and then deliver a swift kick to Carey’s exposed rear end. On occasion he would insist that John Wayne mete out the kick—something that Wayne detested doing, yet performed on demand. “Ford was a bully, he loved to intimidate people,” Carey recalled. “… He was always testing me.” Yet, Carey added, “I couldn’t help but love him.”

John Ford in the garden at the family home on Peak’s Island, Maine, ca. 1926.

He was a man of big emotions, unspoken but not hard to see. After their estrangement, Ford still visited his old friend and film partner Harry Carey Sr. on occasion, but in twenty-five years he hired Carey only once for a part in one of his films. Yet when Carey was dying of cancer in 1948, Ford rushed to his bedside and was there when Carey died. “I remember Jack came out and he took a hold of me and put his head on my breast and cried and the whole front of my sweater was sopping wet all the way down the front,” Carey’s wife, Olive, recalled. “He cried for at least fifteen or twenty minutes, just solid sobbing …”

JOHN FORD ALWAYS INSISTED his films were “a job of work,” nothing more, and throughout the 1930s he worked as a master craftsman laboring in the studio system. He made comedies, tragedies, costume dramas, historical pieces, and adventure stories. But the one genre he could not seem to return to was the one he loved best.

The Western had fallen on hard times by the early 1930s. Part of the problem was the new technology of sound. Westerns looked stiff and artificial on studio soundstages, but authentic audio was hard to record in the great outdoors. In any event, location shooting was costly and complicated, as Ford had found out when he filmed large portions of The Iron Horse in the Sierra Nevadas. Westerns were exiled to the land of the B movie, where they grew undernourished on thin plots, thinner scripts, and actors who often looked ridiculous on horseback. For a while singing cowboys were the rage: Gene Autry, Tex Ritter, and Roy Rogers all became Western movie icons. Children may have squealed with delight, but few adults bothered to watch. The Western became a minor, cut-rate genre.

Ford felt differently. He loved Westerns and was keen to make another. On a long cross-country train trip, his son Pat, then sixteen, read “Stage to Lordsburg,” a short story published in Collier’s magazine by the Western novelist Ernest Haycox. “Read this,” Pat told his father. “I think it’s a movie.”

Haycox’s story was a taut narrative about a handful of disparate stagecoach passengers forced to travel together on a tense journey through hostile Apache territory. Ford saw its possibilities as a thrilling action movie as well as a comedy of manners and social commentary pitting two young iconoclasts—an outlaw and a prostitute—against their purported elders and betters. Ford hoped to film it on an authentic location somewhere away from Hollywood. He set to work with Dudley Nichols, his favorite screenwriter.

Merian Cooper loved the idea of shooting an exciting Western on location, and he arranged a dinner meeting between Ford and David O. Selznick, Cooper’s boss at RKO. At first, Selznick was adamantly opposed to Ford’s wasting his time and talent on what Selznick called “just another Western.” But as Ford and Cooper talked about the project, Selznick slowly began to melt. By the end of the evening, Cooper believed that they had won Selznick’s approval.

“I went into Dave’s office at Pathé [next morning], thinking everything on Stagecoach was just fine,” Cooper recalled thirty years later. “It wasn’t.”

Selznick’s ultimate objection wasn’t to the story but to the cast. He insisted that the picture would fail to “get its print costs back unless we put stars into the two leads.” Selznick suggested Gary Cooper and Marlene Dietrich, both at the height of their careers. Cooper would play the young outlaw, seeking revenge for a brother gunned down by bad men, and Dietrich the kindhearted prostitute who falls in love with him. Both were a little old for their roles, but Selznick was quite certain they would ensure box-office success. John Ford was a great director, Selznick conceded, maybe the greatest, but he didn’t know how to pick the most commercially viable material or package it the right way.

But Ford had already committed to two lesser-known actors. The female lead, Claire Trevor, was a well-respected character actress with impressive credits but hardly the draw that Dietrich could have been. As for the male lead, Ford was proposing to jump off an even higher cliff by choosing a strapping young B-movie actor who was a virtual unknown in the mainstream studios and whose only starring role in a major motion picture, nine years earlier, had proved to be a certified box-office disaster.

Selznick was adamantly opposed. John Wayne, he insisted, could never carry a feature-length film.