In Letters From the East (1889), Rudyard Kipling wrote: “Then, a golden mystery upheaved itself on the horizon – a beautiful, winking wonder that blazed in the sun, of a shape that was neither Muslim dome nor Hindu temple spire. It stood upon a green knoll… ‘There’s the old Shway Dagon,’ said my companion… The golden dome said, ‘This is Burma, and it will be quite unlike any land that one knows about’.”

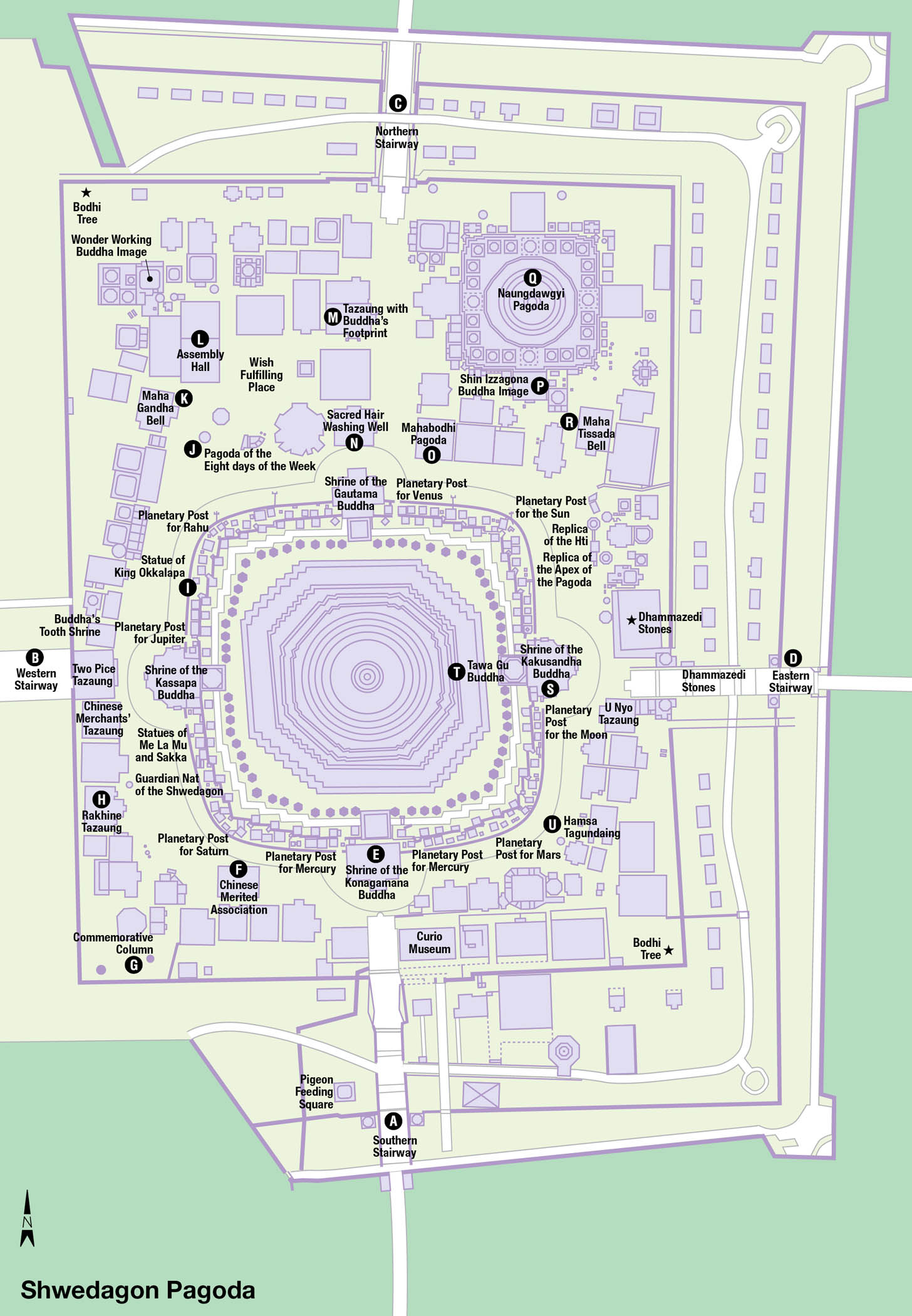

It’s more than 100 years since Kipling sailed up the Rangoon River to the Burmese capital, but the glistening golden stupa of the Shwedagon continues to dominate the city’s skyline. The massive pagoda, said to be around 2,500 years old, is not only a remarkable architectural achievement; it is also the perfect symbol of a country in which Buddhism pervades every aspect of life.

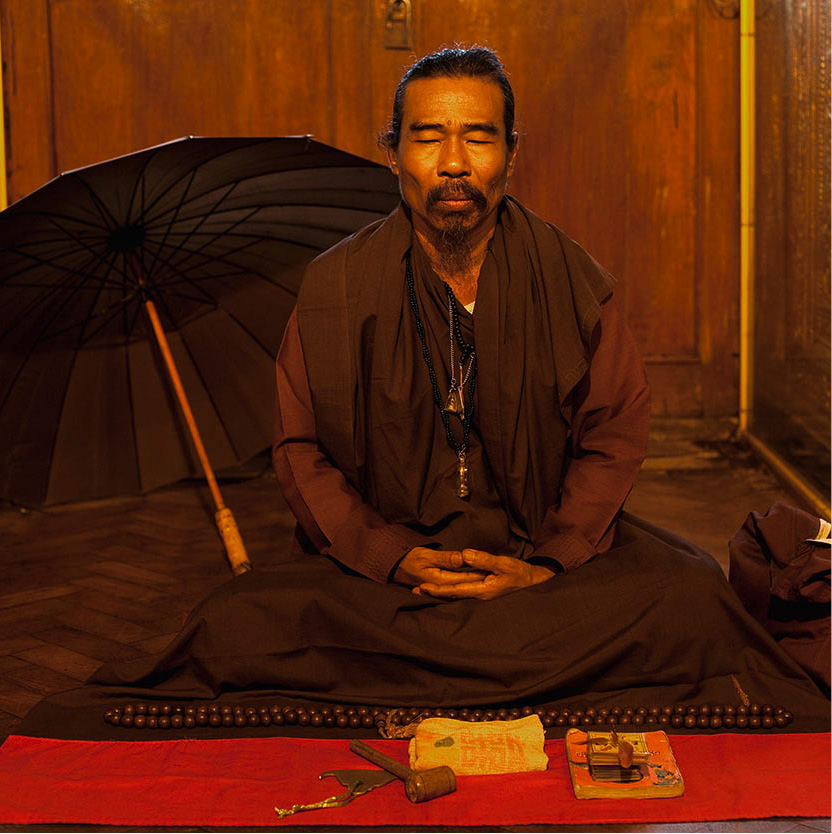

Moments of contemplation at the Shwedagon’s main stupa.

Corrie Wingate/Apa Publications

Crickets for sale in Bogyoke market.

Corrie Wingate/Apa Publications

The Shwedagon may be the undisputed show stealer, but this city holds plenty of less celebrated attractions. Spend a couple of days here and you’ll have time to wander the tree-lined avenues and narrow backstreets of the colonial district downtown, with its court house, city hall and famous Strand Hotel, and to take in a few more pagodas, including the majestic Botataung Paya near the riverside. Re-fuel in a traditional Burmese teahouse before sampling the priceless treasures on show at the National Museum, or mingle with the crowds milling around Bogyoke Aung San market.

The city’s vivid street life makes a lasting impression: the street-side mohinga stalls, where diners dressed in traditional longyis and htameins tuck into bowls of steaming noodles; the ancient, overloaded, green-, cream- and red-painted buses jostling for space at junctions with the streams of trishaws, cycles and taxis; and the open-air markets, whose traders squat beside piles of fresh produce, an outsize cheroot wedged in their mouth, and thanaka paste smeared over their cheeks.

With the country poised on the brink of rapid economic change, modernity is making its presence felt these days, particularly around the striking Sule Pagoda, whose gilded profile is dwarfed by nearby skyscrapers. Yet the overriding impression of Yangon remains one of a city that has altered little since the British slow-marched to their waiting steamers in 1948.

Just across the river, the provincial towns of Thanlyin and Kyauktan hold other splendid Buddhist monuments in striking settings, and provide a welcome respite from the headlong rush of downtown Yangon, while the superb medieval stupas at Bago, a daytrip northwest, tempt many travellers to extend their stay.

A trishaw rider takes a break.

Corrie Wingate/Apa Publications

Getting your bearings

Home to around 5 million people – the population has increased five-fold in three decades – Yangon is surrounded on three sides by water. The Hlaing or Yangon River flows from the Bago Yoma (hills) down its western and southern flanks, past the Shwedagon and picturesque artificial lakes created by the British, which today form the focus of some of the city’s most affluent residential districts. The river then continues through the Delta to the south, dumping its silt-laden waters in the Gulf of Mottama (Martaban).

Sri Lankan chronicles indicate that there was a settlement in the area 2,500 years ago – probably a fishing village or a minor Indian trading colony which grew in fame after the building of the Shwedagon Paya. For centuries, the history of Dagon, as the village was originally known, was inextricably bound to that of the great Shwedagon Pagoda and the nearby town of Syriam (Thanlyin), across the Bago and Hlaing rivers, which was Myanmar’s main port until well into the 18th century.

King Alaungpaya set Dagon on its modern path in 1755, when he captured the village from the Mon, renaming it Yangon (meaning “End of Strife”) and destroying Syriam (Thanlyin) the following year. The British then conquered the town during the First Anglo-Burmese War in 1824, after which its port began to flourish again. Fire caused devastation in 1841 and, in 1852, Yangon was again almost completely destroyed in the course of the Second Anglo-Burmese War, but thrived after the British annexation of the rest of Burma in 1885, becoming capital of the new colony and growing rich on the back of the lucrative trade in teak and other natural resources procured in the north of the country.

Although the city today lies 30km (20 miles) from the open sea, Yangon’s river is easily navigable, and the vast majority of the country’s import and export trade is still handled in the docks at nearby Thanlyin. Industrial suburbs have mushroomed to the north and east, providing work for many of the immigrants flocking to the Yangon area. There is a sizeable Indian community – a hangover from the time when Burma was still a part of British India – as well as a large number of people of Chinese descent, and indigenous ethnic minorities.

Exploring Yangon

The old heritage district downtown is compact enough to explore on foot, albeit with frequent heat-beating pit stops in teahouses and cafés along the way, and allowing plenty of time to navigate the congested pavements, often gridlocked with crowds of shoppers, hawkers, monks and businessmen threading their way between the endless shops and food stalls. However, quite a few of Yangon’s sights lie further afield and are best reached by taxi. Cabs, identifiable by the signs on their roofs, come in a variety of shapes and sizes, but offer great value for money – short trips across downtown cost K1,000–2,000, while you can get from downtown to the northern suburbs for as little as K5000. Moreover, the drivers themselves are considerably more courteous and honest than their counterparts in other Asian cities, and many speak at least a few words of English.

Tip

There’s no better way to kick-start a day’s sightseeing in Yangon than breakfast in a traditional teahouse (For more information, click here).

Sule Pagoda

The logical place to begin any tour of Yangon is the Sule Pagoda 1 [map] (open daily; charge), the shining stupa at the city’s heart which the British used as the centrepiece of their Victorian grid-plan system in the mid-19th century. For centuries a focus of social and religious activity, the richly gilded monument rises from the middle of a busy intersection, surrounded on all sides by shops, swirling traffic and a proliferating number of high-rise hotels and office blocks – a location that belies the stupa’s great antiquity.

Detail of houses and shops, Downtown Yangon.

Corrie Wingate/Apa Publications

Its origins are believed to date back to 230 BC, when a pair of monks, Sona and Uttara, were sent from India as missionaries to Thaton after the Third Buddhist Synod. The King of Thaton gave them permission to build a shrine at the foot of Singuttara Hill in which the monks preserved a hair of the Buddha. The name “Sule Pagoda” itself, however, comes from a later period and is linked to the Sule Nat, or guardian spirit, of Singuttara Hill, who local legend claims showed the monks the site where the relics of three previous Buddhas had been buried. Inside, the pagoda’s shrines and images include four colourful Buddhas with neon halos behind their heads. As with all stupas, it’s traditional (although not obligatory) for visitors to walk around it in a clockwise direction.

As well as its religious significance, the Sule Pagoda is iconic among the Burmese as the venue for several famous political demonstrations over the past three decades, most notably the rally of 1988 when the military opened fire on unarmed protesters, killing and injuring dozens. The monument also formed the focal point of mass gatherings during the Saffron Revolution of 2007.

Tip

Sule Pagoda is the point from which all distances to and from the former capital are officially measured.

Downtown

The orderly blocks of late 19th- and early 20th-century buildings erected by the British on the banks of the Yangon River today comprise the largest collection of colonial architecture in Southeast Asia – a fact all the more remarkable for the general absence in their midst of modern, high-rise constructions. By turns elegant, pompous and flamboyant, the buildings perfectly epitomise the imperious self-confidence of the Raj at its zenith, and lend to the area as a whole an old-world grandiloquence that’s rare for Asian cities of comparable size.

Having been occupied by squatters for decades, many of the structures have lapsed into an advanced state of disrepair, with mildew-streaked walls and peeling plasterwork. The grandest of all, owned by the Burmese government, were deserted completely when the administration decamped to Naypyidaw in 2005. The establishment in 2012 of the Yangon Heritage Trust by leading historian Thant Myint-U was a major step forward, securing a government moratorium on the demolition of all buildings over fifty years old and the attempt to formulate a citywide plan for the protection and restoration of historically significant buildings – although exactly how much can be saved given the city’s current exponential economic remains to be seen.

Tip

Relive the old colonial days at the Strand Hotel by propping up its bar. The once-weekly happy hour on Friday evening is one of the city’s leading social events.

The perfect primer for any tour of Yangon’s colonial district is the massive City Hall 2 [map] on the northeast corner of Sule Pagoda Road and Mahabandoola Street. Erected in 1924, it fuses typically British style with Burmese elements, such as traditional tiered roofs and a peacock seal high over the entrance.

Sule Pagoda seen from the Sky Bistro at the top of the Sakura tower.

Corrie Wingate/Apa Publications

Opposite City Hall spread the lawns of Maha Bandoola Garden 3 [map] (open daily; charge), named after the Burmese military leader of the First Anglo-Burmese War. In the centre of the park, the 46-metre (150ft) Independence Monument comprises an obelisk surrounded by five smaller, 9-metre (30ft) pillars. Formerly known as Fitch Square (after the 16th-century chronicler and trader, Ralph Fitch, who was the first Englishman to visit Burma), the park is popular in the early mornings with t’ai chi practitioners. Facing the square on the east side stands the Queen-Anne-style Supreme Court, dating from 1911.

A few blocks east of here stands the most imposing of all Yangon’s colonial monuments, the vast, neoclassical Secretariat building, sprawling over an entire city block. Dating from 1902, this formerly served as the centre of British power in colonial Burma and also as the national parliament building in post-independence Burma, up until the 1962 military coup. It’s perhaps best known, however, as the place where nationalist leader Aung San and six of his ministers were assassinated in 1947. The entire building is now semi-derelict and its future unclear, with various renovation plans being frequently mooted, but yet to bear fruit.

The red-brick high court and the Independence statue, Mahabandoola Gardens.

Corrie Wingate/Apa Publications

Southeast of the square on Strand Road, it’s impossible to miss the famous Strand Hotel 4 [map], patronised by visitors ranging from Rudyard Kipling and Somerset Maugham to Mick Jagger. After decades in the doldrums, the building was lavishly restored in the mid-1990s, although the lavish makeover and new five-star facilities have rather eroded its original colonial character and charm. Afternoon high tea in the teak-furnished lounge remains a memorable experience, even so, and a lot cheaper than splashing out on one of the hotel’s fabulously expensive rooms.

Monsoon rain at Botataung pagoda.

Corrie Wingate/Apa Publications

The Botataung Pagoda

Heading east on Strand Road for several blocks brings you to the Botataung Pagoda 5 [map]. It is said that when eight Indian monks carried relics of the Buddha here more than 2,000 years ago, 1,000 military officers (botataung) formed a guard of honour at the place where the rebuilt pagoda stands today. The original structure was destroyed by an Allied bomb in November 1943, with rebuilding work beginning on the very first day after independence.

Tip

The area around Sule Pagoda is where you’re most likely to be approached by unofficial moneychangers promising preferable exchange rates – although scams are not unknown, and they’re generally best avoided. For more information, click here.

During the reconstruction work at the very centre of the stupa, a golden casket was found in which were discovered what was claimed to be a hair and two other relics of the Buddha. In addition, about 700 gold, silver and bronze statues were uncovered, as well as a number of terracotta tablets, one of which is inscribed both in Pali and in the south Indian Brahmi script, from which the modern Burmese script developed. Part of the discovery is displayed in the pagoda, but the relics and more valuable objects are locked away. Among these is a tooth of the Buddha which Alaungsithu, a king of Bagan, tried unsuccessfully to acquire from Nan-chao (now China’s Yunnan province) in 1115. China eventually gave it to Burma in 1960. The 40-metre (130ft) bell-shaped stupa is hollow, and visitors can walk around the interior. Look out for the glass mosaic, and the many small alcoves for private meditation. The small lake outside is home to thousands of terrapin turtles; you can feed them with food sold at nearby stalls, thereby acquiring merit for a future existence.

Sugar cane being pressed into juice, Bogyoke market.

Corrie Wingate/Apa Publications

The markets

West of the Sule Pagoda are Yangon’s main street markets. Before World War II, most of the inhabitants of the city were Indian or Chinese, and their influence is still reflected in this jam-packed district. Take a stroll through Chinatown 6 [map], stretching from Shwedagon Pagoda Road, west over 24th, Bo Yawe, Latha and Sint Oh Dan roads, where the cracked sidewalks are piled high with all manner of goods – bamboo baskets, religious images, calligraphy, peanut candy, melon seeds, flowers, dried mushrooms, handmade rice paper, caged songbirds, tropical fish for aquariums and live crabs. In the evening these streets turn into a rambling outdoor restaurant, with stalls offering delicious soups, curries and other local dishes.

Tip

To experience sailing down the Yangon River, go to the Pansodan Street Jetty, near the Strand Hotel, and board one of the frequent ferries for Dalah. It’s about a 10-minute ride costing K4,000/US$4 (for tourists) for the round trip.

A few blocks back towards Sule Pagoda is Yangon’s biggest market, the chaotic Theingyi Zei 7 [map]. Stretching from Mahabandoola Street up to Anawrahta Road, the market occupies two huge buildings divided by a lane in which one of the city’s most colourful vegetable markets is held daily. The southern end of the market is fairly workaday, with hundreds of stalls filled with cheap clothes, textiles, household goods and so on. Further north, towards Anawrahta Road and the Sri Kali Hindu Temple, things take on a much more Indian flavour, with stalls piled high with sacks of aromatic spices, medicinal herbs and mysterious bottled concoctions.

Tip

Visit Bogyoke Aung San Park at night when open-air restaurants offer barbecued food – and in some cases, folkloric performances – in cool surroundings.

The most interesting of Yangon’s bazaars, however, is the Bogyoke Aung San Market 8 [map] (formerly the Scott Market) on Bogyoke Aung San Street on the north side of downtown. Stalls sell a wonderful range of Burmese handicrafts, a wide variety of textiles and craft objects, woodcarvings, lacquerware, dolls, musical instruments, colourful longyis, Shan bags and wickerware. It’s also a good place to shop for jade and gems, with almost all the street-facing shops on the ground floor taken up by jade and jewellery sellers.

Jewellery for sale at Bogyoke Aung San Market.

Corrie Wingate/Apa Publications

Novice monk at the Shwedagon.

Corrie Wingate/Apa Publications

The National Museum

A short taxi ride northwest of the market district on Pyay Road, the National Museum 9 [map] (open Tues–Sun 9.30am–4.30pm; charge) stands in a neighbourhood lined with foreign embassies. The museum’s undisputed showpiece is King Thibaw’s Lion Throne, originally from Mandalay Palace – one of many valuables carried off by the British in 1886 after the Third Anglo-Burmese War. Some items on show here were shipped to the Indian Museum in Calcutta; others were kept in London’s Victoria and Albert Museum. The artefacts were, however, returned to Myanmar as a gesture of goodwill in 1964 after Ne Win’s state visit to Britain. The wooden throne, 8 metres (27ft) tall and inlaid with gold and lacquerwork, is a particularly striking example of the Burmese art of woodcarving. Among the Mandalay Regalia are gem-studded arms, swords, jewellery and serving dishes. Artefacts from Burma’s early history in Beikthano, Thayekhittaya and Bagan in the museum’s archaeological section include an 18th-century bronze cannon and a crocodile-shaped harp.

The Shwedagon Pagoda

“The Shwe Dagon rose superb, glistening with its gold, like a sudden hope in the dark night of the soul of which the mystics write glistening against the fog and smoke of the thriving city.” – W. Somerset Maugham, The Gentleman in the Parlour (1930)

The Shwedagon Pagoda.

Corrie Wingate/Apa Publications

Few religious monuments in the world cast as powerful a spell as Yangon’s Shwedagon Pagoda ) [map] (open daily 4am–10pm; charge), the gigantic golden stupa rising on the northern fringes of the city. The holiest of holies for Burmese Buddhists, it’s also a potent symbol of national identity, and in recent decades has become a rallying point for the pro-democracy movement.

Its unique sanctity derives from the belief that the stupa enshrines relics not merely of the historical Buddha, Gautama, but also those of three of his predecessors. No one, however, has been able to confirm whether or not the eight hairs of the Master actually lie sealed deep inside the stupa, as the structure would have to be partly destroyed to reach its solid core – something the shrine’s custodians will never permit.

It’s tempting when you arrive in Yangon to head straight for the mesmerising gilded spire on the horizon, but resist the urge if you can until early evening, when the warm light of sunset has a transformative effect on the gold-encrusted pagoda and its myriad subsidiary shrines.

Tip

Try not to limit yourself to a single visit to the Shwedagon Pagoda, whose appearance and atmosphere changes mysteriously with the shifting light.

The complex can be entered via four different flights of covered steps. Whichever stairway you use, be sure to remove your footwear at the bottom of the steps.

The Shwedagon still dominates the city skyline.

iStock

History of the Shwedagon

Although the origins of the Shwedagon are shrouded in legend (For more information, click here), it is known that the site was well-established on the pilgrimage circuit by the 11th century. Queen Shinsawpu (r.1453–72) is revered for giving the pagoda its present shape and form. She established the terraces and walls around the stupa, and donated her weight in gold (40kg/90lbs) to be beaten into gilt leaf and used to plate the pagoda.

King Hsinbyushin of the Konbaung dynasty raised the stupa to its current height of 99 metres (325ft) after a devastating earthquake in 1768 brought down the top of the spire. His son, Singu, had a 23-tonne bronze bell cast; known as Maha Ganda, it can be found today on the northwest side of the main pagoda platform. The British pillaged Shwegadon during their 1824–26 wartime occupation and tried to carry the bell to Calcutta, but the ill-fated object fell into the river. A third bell weighing more than 40 tonnes was donated by King Tharrawaddy in 1841: it sits today on the northeast side of the pagoda enclosure.

In 1931 the pagoda was seriously damaged in a fire, and has suffered from the effects of several earthquakes in recent years. Yet for all the Shwedagon’s roller-coaster history, the Burmese are convinced no lasting damage can befall it.

The stairways (zaungdan)

The passageway most commonly used by visitors to the Shwedagon is the Southern Stairway A [map], which ascends from the direction of the city centre. Its 104 steps lead from Shwedagon Pagoda Road to the main platform. The entrance is guarded (as are the northern and western staircases) by a pair of towering chinthe, a mythological leogryph, half lion and half-griffin. If you’re not up to the climb, note that this stairway also boasts a lift, as does the entrance on the northern side.

The Shwedagon at dusk, seen from the Northern exit.

Corrie Wingate/Apa Publications

The Western Stairway B [map], which leads up from U Wisara Road, was damaged during the Second Anglo-Burmese War and kept closed by soldiers from the British garrison. In 1931, a stall at the foot of the stairs caught fire. The blaze raced up and around the northern flank of the Shwedagon, causing severe damage to the precincts before being halted on the eastern stairway; unfortunately not in time to save many ancient monuments.

The little-used Western Stairway is the longest zaungdan with 166 steps (although an escalator running up the middle now removes the effort of walking up). The landing on the platform bears the name Two Pice Tazaung because of the contribution of two pice (a small copper coin) given daily by Buddhist businessmen and bazaar-stallholders for the stairway’s reconstruction.

The Northern Stairway C [map] was built in 1460 by Queen Shinsawbu, and has 128 steps, with decorative borders shaped like crocodiles. Two water tanks can be seen to the north of the stairway; the one on the right is called thwezekan, meaning “blood wash-tank”. The name derives from a popular legend recounting how, during King Anawrahta’s conquest of the Mon capital Thaton, his commander-in-chief, Kyanzittha, used the tank to clean his blood-stained weapons.

The Eastern Stairway D [map] is much like an extension of the Bahan bazaar, which lies between Kandawgyi Lake and the Shwedagon. This flight of 118 steps suffered particularly heavy damage during the British attack on the pagoda in 1852.

The terrace

A magnificent spectacle greets visitors emerging from the half-darkness of the covered stairways. In Somerset Maugham’s words: “At last we reached the great terrace. All about, shrines and pagodas were jumbled pell-mell with the confusion with which trees grow in the jungle. They had been built without design or symmetry, but in the darkness, their gold and marble faintly gleaming, they had a fantastic richness. And then, emerging from among them like a great ship surrounded by lighters, rose dim, severe and splendid, the Shwe Dagon.”

Washing the Buddha statue on the planetary post for the moon, Shwedagon.

Corrie Wingate/Apa Publications

The terrace was created in the 15th century when the rulers of Bago levelled off the top of the 58-metre (190ft) -high Singuttara Hill, since when it’s been embellished with a fabulous profusion of prayer pavilions (tazaung) and resting places (zayat) topped with innumerable spiky pyatthat roofs layered in tiers of five, seven or nine. The floor of the terrace is inlaid with marble slabs, which can get very hot under bare feet by the middle of the day – a mat pathway is sometimes laid out.

The stupa

From the centre of the platform rises the gold-covered stupa itself, the reflected light from which casts an ethereal glow over the forest of subsidiary shrines, temples, pavilions and elaborately roofed halls below. Rising to a height of 99 metres (325ft) and with a circumference of 433 metres (1,421ft), the zedi adheres to traditional Burmese design, divided into distinct sections, each with its particular symbolic significance.

Wooden souvenirs outside the Shwedagon Pagoda.

Corrie Wingate/Apa Publications

The base, or plinth (paccaya) rising from the main terrace is octagonal and on each of its eight sides rest eight smaller stupas – 64 in all. The four larger stupas opposite the stairways mark the cardinal points. At each of the platform’s four corners are manokthiha (sphinxes), each surrounded by several chinthe.

The stepped terraces of the base, which only monks are permitted to access, merge into the stupa’s elegantly curved “bell” (khaung laung bon), which is divided from the so-called “inverted alms bowl” (thabeik) by the “turban band” (baungyit). Above the bowl rests one of the most delicately embellished elements, representing 16 lotus petals (kyahlan), which in turn give way to the uppermost section, or conical spire. This begins with a distinctively shaped banana bud (hnget pyaw bu) on which sits the 10-metre (33ft) hti, or umbrella, decorated with 1,485 gold and silver bells, 5,448 diamonds, and 2,317 rubies, sapphires and other precious stones. An enormous emerald sits in its centre to catch the first and last rays of the sun. Finally, crowning the very top of the monument is the golden orb (seinbu), tipped with a single, exquisite 76-carat diamond.

Fact

An extraordinary quantity of gold was deployed in the decoration of the Shwedagon Pagoda: 8,688 solid bars were used on the bottom section alone, and 13,353 on the upper.

Around the terrace

A constant swirl of activity surrounds the great stupa, as worshippers make their ritual circumambulation of the monument, pausing to pray and perform rituals at the numerous shrines and planetary posts along the way. The circuit is always performed in a clockwise direction.

Maha Wizaya Pagoda, next to the Shwedagon.

Corrie Wingate/Apa Publications

Directly opposite the top of the southern stairway stands the Shrine of the Konagamana Buddha E [map] (signed “Kawnagammana”), home to some of the pagoda’s oldest Buddha statues. This is one of four shrines attached to the base of the main stupa at the four cardinal points, each dedicated to one of the four Buddhas of the current world cycle – Konagamana, Kakusandha, Kassapa and the historical Buddha, Gautama – whose relics are believed to be enshrined in the pagoda. On either side of the shrine stand Planetary Posts for Mercury (Monday), one of eight such planetary posts around the stupa, which worshippers venerate according to the day of the week on which they were born.

On the southwestern side of the stupa is the pavilion of the Chinese Merited Association F [map], home to a single solid jade Buddha decorated with 2.5kg of gold, while immediately behind stands the striking Sun–Moon Buddha, flanked with images of a peacock and a hare (symbolizing the sun and moon respectively). Nearby, a Commemorative Column G [map], inscribed in Burmese, English, French and Russian, honours the 1920 student revolt which sparked Burma’s drive for independence from Britain.

Continuing down this side of the platform, you’ll soon reach the Rakhine Tazaung H [map], beautifully decorated with intricate woodcarvings. Built by two wealthy merchants from Rakhine, the pavilion is home to an 8.5-metre (28ft) reclining Buddha, while pictures on the rear wall depict the legend of the founding of the Kyaiktiyo Pagoda (For more information, click here).

Just past the top of the western stairs a small pavilion covered in dazzling glass mosaics holds a replica of the Buddha’s Tooth housed in the Temple of the Tooth in Kandy, Sri Lanka. Behind the Buddha’s Tooth pavilion, a museum houses various items gifted to the pagoda over the years, while slightly further on, standing on the base of the main stupa, is a small image of the legendary King Okkalapa I [map], the founder of the Shwedagon, standing beneath a white umbrella, the symbol of royalty.

In an open area to the northwest of the stupa is a small octagonal pagoda known as the Pagoda of the Eight Days of the Week J [map], whose sides hold niches containing small Buddha images, each with the figure of an animal placed above it, corresponding to the eight Burmese days of the week (equivalent to the seven days of the western week, plus an extra day for Wednesday, which is divided into morning and afternoon). Behind it is the huge bronze Maha Gandha Bell K [map], which King Singu had cast in 1779 and which was raised from the Yangon River in 1825 after the British attempted to steal it. The bell weighs 23 tonnes and is 2.2 metres (over 7ft) tall. The Assembly Hall L [map] opposite houses a 9-metre (30ft) Buddha image in earth-witness pose..

In the far northwest corner of the terrace is one of the half dozen or so Bodhi Trees, decorated with flowers and small flags, which stands around the edge of the enclosure. Some are said to have been grown from a cutting taken from the holy Bodhi tree in Bodhgaya, India, under which the Gautama Buddha gained enlightenment (or at least from the venerable Sri Maha Bodhi Tree in Anuradhapura, Sri Lanka, which was itself grown from a cutting taken from original Indian tree).

Returning to the main part of the pavilion, you’ll notice an especially busy area. This is known as the Wish Fulfilling Place, where devotees kneel, facing the great stupa, and earnestly pray that their wishes will come true. Behind here an airy pavilion houses the huge seated Chanthargyi Buddha, the largest Buddha image in the entire pagoda. In a nearby cluster of pavilions not far from the north entrance is the Tazaung with Buddha’s Footprint M [map] (on the left just before you reach the top of the northern stairway). Life-sized statues of Indian guards stand in front of this hall, while the footprint (chidawya) itself is divided into 108 sections, each of which has a special significance.

Between the library and the stupa is the Sacred Hair Relic Washing Well (signed “Hsandawtwin”) N [map], built in 1879 over the spring in which, according to legend, the Buddha’s eight hairs were washed before they were enshrined. The spring is said to be fed by the Ayeyarwady River.

Attached to the base of the main stupa on its northern side is the Shrine of Gautama Buddha, dedicated to the current, historical Buddha whose world dominion, it is believed, will last until the 45th century. Across the platform stands the multi-coloured Mahabodhi Pagoda O [map], a replica of the original pagoda of the same name in Bodhgaya, its distinctive Indian architecture strikingly out of place amongst the Burmese-style monuments which surround it.

Just past here, another pavilion houses the Shin Izzagona Buddha Image P [map] housing a Buddha statue with large eyes of different sizes which is said to have been erected by, or for, Shin Izzagona, a zawgyi (alchemist) from Bagan’s early period. According to legend, Izzagona’s obsession with discovering the Philosopher’s Stone, the mythical substance said to be able to change base metals to gold or silver, plunged the country into poverty. When his final experiment was about to end in failure, he poked out both his eyes to satisfy the king. In his final casting, however, Izzagona did produce the Philosopher’s Stone, and immediately sent his assistant to the slaughterhouse to obtain two eyes that would, with the stone’s help, allow him to regain his sight. The assistant returned with one eye from a goat and another from a bull; from that time on, Shin Itzagona was known as “Goat-Bull Monk”.

Just to the north is the striking Naungdawgyi Pagoda Q [map], looking like a scaled-down version of the main stupas and said to mark the spot where the eight hairs of the Buddha, carried by the merchants Tapussa and Bhallika, were originally kept. Nearby is the Maha Tissada Bell R [map], commissioned by King Tharrawaddy in 1841. It weighs almost 42 tonnes, is 2.55 metres (8ft 4in) tall and has a diameter of 2.3 metres (7ft 6in) at its mouth.

Just before you reach the top of the Eastern Stairway, an open-sided pavilions houses the celebrated Dhammazedi Stone Inscription, commissioned in 1485 by King Dhammazedi and recording the history of the pagoda up to that date in Burmese, Mon and Pali three huge stone slabs. The tazaung which originally housed these stones was one of the last buildings destroyed by the 1931 fire before the blaze was finally brought under control. King Dhammazedi, himself a zawgyi, has gone down in Burmese history as the “master of the runes”.

Opposite the Eastern Stairway is the Temple of the Kakusandha Buddha S [map], built by Ma May Gale, the wife of King Tharrawaddy, though later destroyed by the fire of 1931. The temple was rebuilt in its original style in 1940. The Buddha figure in this tazaung is unusual in that the palm of its right hand is turned upwards; three of the four smaller Buddha figures in front of the niche are also depicted in this unfamiliar posture. Behind the temple, in a niche on the eastern side of the upper platform, is the Tawa Gu Buddha T [map] statue, which is said to be able to work miracles, although from the terrace is rather tricky to see.

Close to the southeast corner of the platform is a Hamsa Tagundaing U [map] or prayer pillar. Such columns are said to guarantee the health, prosperity and success of their founders.

Tip

The best way to nip between sights uptown is to wave down a cab as and when you need one, rather than book a car and driver for the day. Taxis are cheap and plentiful across the city.

At the far southeastern corner of the terrace is another of the pagoda’s various Bodhi Trees which, like its cousin in the northwest corner, is said to be descended from the original at Bodhgaya. On the octagonal base which surrounds it is a huge Buddha statue.

Part of the way down the Southern Stairway you will find a Pigeon Feeding Square. Pagoda pilgrims can buy food here to feed the dozens of pigeons, thereby earning merit for a future existence.

Around the Shwedagon Pagoda

Numerous sites of religious and cultural interest lie dotted around the Shwedagon Pagoda, an area which after Independence became the spiritual nerve centre of the fledgling Burmese nation.

Maha Wizaya Pagoda

A short distance southeast of the Pagoda, on the opposite side of U Htaung Bo Road, the Maha Wizaya Pagoda ! [map] was built in 1980 using public donations to commemorate the unification of all Theravada orders in Burma. The interior of the main stupa is completely hollow, its circular central hall curiously decorated to resemble a forest at night, with mysterious astrological symbol placed in the faux-sky overhead.

Dargah of Bahadur Shah

One of Yangon’s rare Muslim monuments lies on an inconspicuous side street just south of the Shwedagon Pagoda. The Dargah of Bahadur Zafar Shah @ [map], at 6 Ziwaka Road, is the final resting place of India’s last Mughal emperor, who spent the final four years of his life at a house on the spot. An erudite, religiously tolerant and sensitive polymath with a talent for Islamic calligraphy and poetry, Zafar somewhat reluctantly became a rallying point for the mutinous sepoys in the ill-fated Indian Uprising of 1857 – and paid dearly for backing the wrong side. After the rebellion had been crushed, the British all but destroyed his former capital and palace, executing thousands and dispatching the king and the few surviving members of his family into permanent exile in Burma, where he died in 1862.

The exact whereabouts of the grave, which the colonial authorities kept secret for fear that it would become a martyr’s shrine, was revealed in 1991 when workmen digging foundations for a mausoleum near the site of Zafar’s former house came across a brick-covered structure 1.1 metres (3.5ft) beneath the surface. It turned out to be the grave of the last Mughal, alongside that of his wife and grandson. Since his death, the former ruler has come to be regarded as a latter-day saint and his modern tomb is now a place of pilgrimage for Indian Muslims. The three silk-covered tombs on the ground floor are for show; the real ones lie hidden in a tiled crypt below, which the caretaker can unlock on request.

Martyrs’ Mausoleum

Also worth a visit in this area is the Martyrs’ Mausoleum £ [map], which crowns a low hill to the north of the Shwedagon Pagoda, beyond Arzarni Road. This patriotic monument contains the tombs of Aung San, leader of the Burmese independence movement (and father of Aung San Suu Kyi) along with those of the six ministers who were assassinated alongside Aung San during a cabinet meeting in 1947. Aung San was only 32 at the time. The pre-World War II prime minister, U Saw, was subsequently found to be the instigator of the plot, and was executed the following year, together with the hired assassins. The mausoleum is also notorious as the site of the bombing of October 1983 which killed 21 people, including three South Korean ministers who were accompanying their President on a state visit. Members of the North Korean army were later found to have carried out the attack.

Reclining Buddha at Kyauk Htat Gyi Pagoda.

Corrie Wingate/Apa Publications

Nga Htat Gyi Pagoda and Kyauk Htat Gyi Pagoda

From the mausoleum, if you take the northern exit on to Shwegondaing Road, turn right and follow the main road northwest for ten minutes, you’ll reach the spectacular Nga Htat Gyi Pagoda $ [map], in which a huge sitting Buddha, dating from 1558, resides in an early 20th-century shrine. Called the “five-storey Buddha” because of its size, the figure is unique for the huge, flame-like pieces of gilded armour, or “magites”, protruding from his giant head and shoulders.

On the opposite side of Shwegondaing Road, Kyauk Htat Gyi Pagoda % [map] (aka Chaukhtatgyi Pagoda), lies only five minutes’ walk away. Not really a pagoda in the traditional sense, the Kyaukhtatgyi is actually a tazaung (pavilion) housing a colossal, 70-metre (230-ft) reclining Buddha. Although the sculpture is bigger than the reclining Shwethalyaung Buddha of Bago, it is not as well-known or as highly venerated. Elsewhere in the pagoda enclosure is a centre devoted to the study of sacred Buddhist manuscripts. The 600 monks who live in the monastery annex spend their days meditating and studying the old Pali texts.

Koe Htat Gyi

You’ll need to jump in a cab to visit the last of the major religious sites in the Shwegadon area. The Koe Htat Gyi ^ [map] (literally “Nine Storey”) Pagoda lies a 10–15-minute drive west on Bargaya Road, a stone’s throw from the river. Its centrepiece is a 20-metre (65ft) -high sitting Buddha, with eerily life-like eyes made from blown glass. Inside the figure, a small casket is said to contain relics of the historical Buddha, as well as those of some of his disciples. In the area surrounding the complex are a great many kyaung (monasteries) where early birds can watch the monks emerging onto the streets to fill their alms bowls just after sunrise.

Old jeeps, Downtown Yangon.

Corrie Wingate/Apa Publications

Parks and lakes

Yangon boasts more than a dozen public parks and gardens, and locals take great pleasure in spending the hot hours of the day resting in them, preferably beside a lake. Just east of the Shwedagon Pagoda, the northern shore of Kandawgyi (“Royal”) Lake is given over to Bogyoke Aung San Park & [map], dedicated to the country’s most famous martyr, whose children’s playgrounds and picnic areas are popular attractions with young families. An attractive boardwalk runs around the southern part of the lake, although foreigners are charged $2 for the privilege of using it, and the adjacent road, although less atmospheric, offers similar views and is free.

The park’s best-known sight is the surreal Karaweik Palace * [map], on the eastern shore. Constructed in the early 1970s, the structure replicates a pyigyimun, or royal barge, such as those Burma’s kings and queens would traditionally have used on ceremonial occasions. It’s actually a building rather than a boat, contrary to appearances, with its double bow depicting the mythological karaweik, a water bird from Indian prehistory, and a multi-tiered pagoda on top. The equally sumptuous interior contains some striking lacquerwork embellished with mosaics in glass, marble and mother-of-pearl. It now houses a restaurant which hosts popular buffet dinners every evening at 6.30pm (US$20 per head, payable in dollars) featuring a cultural show including music, classical dance and puppetry.

Ornate Karaweik Palace restaurant, Kandawgyi Lake.

Corrie Wingate/Apa Publications

Inya Lake and around

Continuing north from the Shwedagon Pagoda along busy Kaba Aye Pagoda Road you’ll arrive at enormous Inya Lake ( [map]. As well as the Yangon University campus, the lush area surrounding it holds some of the city’s most prized real estate and exclusive neighbourhoods, including the British-era home of NLD leader, Aung San Suu Kyi on University Avenue, while further down the same street is the former home of her old adversary and long-time military ruler, Ne Win. Next to the university, the 15-hectare (37-acre) lakeside park is the most popular place in the city for romantic trysts – images of amorous couples schmoozing on the grassy verges are a cliché of Burmese movies and popular song videos.

The southwest corner of the lake, by contrast, is tainted with much darker associations. During the civil unrest of 1988, an estimated 283 students were beaten to death or drowned by military police on the shore – an event dubbed the “White Bridge Massacre”. A further 3,000 or more people are thought to have lost their lives in the brutal crackdown that ensued.

Fact

In 2009, an American wellwisher swam across Inya Lake to visit Aung San Suu Kyi while she was under house arrest, resulting in an increase in her sentence.

With its prize exhibits now moved to a display in the new Burmese capital, Naypyidaw, the government-run Gems Museum, at 66 Kaba Aye Pagoda Road (Tues–Sun 9am–4pm; charge), just north of Inya Lake, has some interesting exhibits showcasing Myanmar’s incredible mineral wealth, as well as a whole floor of jewellery emporia where you can purchase objects fashioned from Burmese jade and precious stones.

The Kaba Aye Pagoda and Mahapasana Cave

Immediately northeast of Inya Lake is the Kaba Aye Pagoda , [map], which the first prime minister of independent Burma, U Nu, built in the early 1950s. Legend has it that an old man dressed in white appeared before the monk Saya Htay while the latter was meditating near the town of Pakokku on the Ayeyarwady River, handing him a bamboo pole covered with writing. He then asked Saya Htay to pass the pole on to U Nu, accompanied by a demand that the prime minister actively do more for Buddhism.

A walkway filled with souvenirs at the Kaba Aye Pagoda.

Corrie Wingate/Apa Publications

U Nu was as well versed in religious affairs as in politics, and not only received the bamboo pole but amazingly complied with the old man’s demand. The country’s leader built the Kaba Aye Pagoda about 12km (8 miles) north of downtown Yangon in preparation for the Sixth Buddhist Synod of 1954 to 1956, and dedicated it to the cause of world peace.

Although lacking some of the aesthetic appeal that distinguishes the other Yangon pagodas, the Kaba Aye is interesting. It is circular in shape, and contains relics of the two most important disciples of the Buddha, discovered in 1851 by an English general; they were only returned to their rightful place in the Kaba Aye Pagoda after spending many years at the British Museum in London. Opposite each of the five pagoda entrances stand 2.4-metre (8ft) -high Buddha statues. A platform holds another 28 small gold-plated statues that represent previous Buddhas. Some 500kg (1,100lbs) of silver were required to cast the central Buddha figure in the inner temple.

Meditating inside Botataung pagoda

Corrie Wingate/Apa Publications

In the grounds of the Kaba Aye Pagoda is the Maha Pasana Guha (“Great Cave”), capable of holding up to 10,000 people, which U Nu also had specially built for the Sixth Buddhist Synod. It is supposed to resemble India’s Satta Panni Cave, where the First Buddhist Synod took place shortly after the death of Gautama. Devout Buddhist volunteers completed the project only three days before the start of the Synod in 1954. When the Synod ended, the Institute for Advanced Buddhist Studies was founded with its headquarters in the Kaba Aye Pagoda compound. Funds from the Ford Foundation contributed to the construction of its handsome main building, which successfully blends elements of modern architecture with traditional symbolism.

In December 1996, during a ritual when pilgrims were streaming through to see a tooth relic of the Buddha, the complex was the scene of a bomb attack that killed five people and injured dozens more. The atrocity is thought to have been mounted by the military regime as part of a campaign to provide justification for a crackdown on political opposition.

Meditation courses

As a profoundly Buddhist nation, Myanmar attracts individuals from all over the world who wish to study the art of meditation. Residential courses are offered by several monasteries in and around Yangon, lasting anything from a week to several months. The best-known venue is the Mahasi Meditation Centre (www.mahasi.org.mm), established by the esteemed Mahasi Sayadaw in 1947. The programme is not for the uncommitted: the day typically begins at 3am and ends at 11pm, and on some courses students are required to remain utterly silent for the duration of their stay. Another well-regarded place is the Dahmma Joti Vipassana Centre, near the Chauk Htat Gyi Pagoda (www.joti.dhamma.org; donation).

Making a call on the public phones, Downtown Yangon.

Corrie Wingate/Apa Publications

The Northern Outskirts

A couple of sights on Yangon’s northern outskirts may tempt you to break a journey to or from the city’s international airport.

The Mai La Mu Pagoda ⁄ [map], in the suburb of Okkalapa, is named after the mother of King Okkalapa, founder of Dagon and original donor of the Shwedagon. According to legend, Mai La Mu – said to have been born from a mango (me-lu) tree and raised by a hermit – had this pagoda built to alleviate her grief after the untimely death of her young grandson. Her statue can still be seen on the southwestern flank of the Shwedagon Pagoda. The complex is a wonderland of gilded spires and vibrantly painted statues including interesting illustrations and figures from the Jataka tales, depicting the Buddha in earlier lives and fashioned in a singularly Burmese style. The pagoda also holds a large reclining Buddha.

Taukkyan British war cemetery.

Corrie Wingate/Apa Publications

West of the airport, in the township of Insein, stands the Ah Lain Nga Sint Pagoda ¤ [map] – a centre of worship for adherents of the branch of Burmese Buddhism that places great emphasis on the occult and supernatural phenomena. The grounds contain a five-storey tower, a hall with statues of all kinds of occult figures, and a kyaung which serves as a residence for monks.

Lawka Chantha Abhaya Labha Muni.

Corrie Wingate/Apa Publications

Lawka Chantha Abhaya Labha Muni and Elephant Park

A popular visitor destination in the northern suburbs of Yangon is the temple housing the enormous Lawka Chantha Abhaya Labha Muni ‹ [map] statue. Carved from a single block of white marble, the 11-metre (37ft) -tall image was sculpted in 1999–2000 and installed in a lavish new shrine paid for by the military government.

An auspicious move

One of the ways in which the kings of ancient Burma expressed their wealth and power – and acquired cosmic merit at the same time – was by creating huge stone Buddhas. In 2000, the country’s military generals revived the tradition with the arrival at a purpose-built hilltop temple on the outskirts of Yangon of a giant Buddha carved from a single block of flawless white marble.

The boulder used to make it had been discovered the previous year by master sculptor, U Taw Taw, at the famous quarry of Sangyin, near Mandalay. It took him and his sons twelve months to carve. Recognising the PR potential of sponsoring the project, the generals spared no expense to bring the 600-tonne colossus to Yangon, constructing a special 8-rail train line to transport it to the Ayeyarwady, and a huge golden barge to ship it downriver. The 12-day trip, featuring a flotilla of vessels, was cheered from the banks by vast crowds. Another specially laid rail line conveyed the statue to its new home atop Mindhamma Hill, where the 11-metre (37ft) image – christened Lawka Chantha Abhaya Labha Muni – was enshrined inside a giant glass case. Attracting constant streams of devotees, the mighty white Buddha is today one of Yangon’s most popular religious attractions.

Less than five minutes from the new temple, on Mindhamma Road in Inthein Township, is the site of another prestige-winning initiative by the Burmese junta. The leafy Hsin Hpyu Daw Elephant Park › [map] (daily 9am–5pm; free) is where the government houses a trio of rare white elephants. Such creatures are traditionally regarded as conferring good luck on a country’s rulers and have been much sought after by the infamously superstitious military regime. In fact, the elephants aren’t so much white as reddish-brown (or pink when they’re wet) – technically albinos, hence the importance of shade to keep their fragile skin out of the sun. Pampered they may be with nutritious food and regular baths in a specially built waterfall, but the spectacle of such dignified creatures hobbled with chains in a cramped concrete pagoda is unlikely to inspire animal-lovers.

Around Yangon

In addition to the pottery town of Twante on the Ayeyarwady Delta (For more information, click here), a couple of other destinations across the Bago River offer escape from the crowds and noise of Yangon. Foremost among them is the port of Thanlyin, overlooked by a particularly wonderful hilltop pagoda. Half an hour further south, Kyauktan is the site of another pretty Buddhist shrine, this time marooned on an islet. Finally, heading northwest towards Bago and the Sittaung Valley, a recommended stop for anyone interested in the events of World War II is the Taukkyan War Cemetery, where thousands of graves and memorial plaques commemorate the fallen of Allied and Commonwealth countries.

Tip

The most practical means of exploring the sights between Thanlyin and Yangon is to hire a taxi for the day (roughly US$60–100).

Thanlyin and Kyauktan

The city of Thanlyin fi [map] (formerly Syriam), on the opposite side of the Bago River from Yangon, has served for centuries as Burma’s principal harbour – a role it continues to play thanks to the modern deep-water container port of Thilawa installed on its waterfront. Most of the country’s trade passes through here, making this something of an industrial boom city, with a population that quadrupled in the 1980s following the construction of a bridge connecting it with Yangon and which is now nudging the 200,000 mark. The main incentive to make the traverse is to visit the wonderful hilltop pagoda of Kyaik-Khauk, on Thanlyin’s southern outskirts, and to hop on a ferry to the atmospheric Yele Paya temple at nearby Kyauktan – both of which provide a welcome change of scene from the hectic streets, fumes and traffic of the metropolis.

The seeming absence of ancient monuments in the city belies the fact that it has played a seminal role in Burmese history. A major port since the time of the Hindu Andhran dynasty in the 2nd century BC, it rose to national prominence after being captured by the Kingdom of Arakan in the late 16th century. The invading army was led by the maverick Portuguese soldier of fortune Felipe de Brito y Nicote, who’d left Lisbon decades earlier as a cabin boy (For more information, click here).

Aside from a weed-choked Catholic church on the roadside, precious little has survived from the Portuguese interlude. The main focus for day-trippers is the much more ancient Kayaik-Khauk Pagoda (free), rising from a low hill on the southern fringes of Thanlyin. Inscriptions suggest a stupa may have been erected on the site as long ago as the third century AD, but the present structure, said to hold hairs of the historical Buddha, is around 700–800 years old. A smaller version of the Shwedagon, it is exquisitely gilded and affords grandiose views across the city and surrounding countryside.

At Kyauktan fl [map], about 15km (9 miles) south of Thanlyin on a tributary of the Yangon River, the Ye Le Pagoda (charge) is famous for its unusual situation – on an islet in the river. Foreign visitors have to travel to it in a special launch.

Tip

If you’re in the area in late January, it’s worth trying to coincide your visit with the Thaipusam festival, in which local Tamil devotees of the Hindu God Murugan stick skewers through their cheeks and walk on hot coals.

With its gilded upturned eaves, seven-tiered roofs and frame of swaying palm trees, the temple itself is an architectural gem, while locals also visit to feed the huge catfish which hang around the temple waters. Access to the temple is by boat – a one-minute crossing for which foreign tourists are charged a disproportionate $5 return.

Taukkyan War Cemetery

Just off the main Yangon–Bago highway, 35km (21miles) north of the city, Taukkyan ‡ [map] (Htauk Kyant; daily 7–11am & 1–4.30pm; free) is the largest of Burma’s major war cemeteries. It holds the graves of 6,374 Allied and Commonwealth servicemen killed in World War II, as well as memorial plaques listing the names of 27,000 more whose bodies were never found or identified. A large proportion of them were from India and Africa. Maintained by the Commonwealth War Graves Commission, the site is impeccably well kept and a moving tribute to the mainly young men who lost their lives fighting the Japanese in the early 1940s.

The legend of Shwedagon

Myanmar’s most famous sight has a long history, with its origins shrouded in legend.

The legend of the Shwedagon Pagoda is recorded in Myanmar’s great historical epic, The Great Glass Palace Chronicle, which was compiled in Mandalay during the early 1830s by a royal commission made up of learned monks, brahmins and lay scholars. According to the traditional narrative, the story of the pagoda goes back 2,500 years and centres on Okkalapa, King of Suvannabhumi, who lived near Singuttara Hill in Lower Burma during the time when Siddhartha Gautama was still a young man in northern India. The hill is considered holy because of the relics of three Buddhas enshrined on its summit. Local belief asserts that a new Buddha comes into existence every 5,000 years. As nearly 5,000 years have elapsed since the time of the last Buddha, it was thought that the hill would lose its blessedness unless a new incarnation offered a gift to be enshrined as a relic for the next five millennia. To this end Okkalapa spent many hours on the hill meditating and praying.

In India, meanwhile, Gautama was close to achieving enlightenment under the Bodhi tree in Bodhgaya. Buddhist chronicles assert that he appeared before Okkalapa and promised that the king’s wish would be granted. Gautama meditated under the Bodhi tree for 49 days before he accepted his first gift from his disciples: a honey cake offered by Tapussa and Bhallika, two Burmese merchant brothers who had come from the village of Okkala. To express his gratitude, Gautama plucked eight hairs from his head and gave them to the brothers, who then set off on a difficult return journey. First, they were robbed of two of the Buddha’s hairs by the King of Ajetta. Then, while crossing the Bay of Bengal, another couple of hairs were taken by the seabed-dwelling King of the Nagas. Despite the losses, the brothers were welcomed by Okkalapa who held a great feast attended by all the native gods and nat, who decided a grand stupa should be built to house the relics.

When Okkalapa opened the casket containing the Buddha’s hairs, lo and behold, he saw eight hairs in place. As he looked on in astonishment, the strands emitted a brilliant light that rose high above the trees, radiating to all corners of the world. Suddenly, the blind everywhere could see, the deaf could hear, the dumb could speak and the lame could walk. As this miracle took place, the earth shook and bolts of lightning flashed. The trees blossomed and a shower of precious stones rained onto the ground.

Enshrining the relics

As a result of the legend of the hairs, the site chosen to enshrine the Buddha’s hairs – Singuttara Hill – is considered one of the country’s most sacred places, and the golden Shwedagon Pagoda is regarded as the holiest of the country’s pagodas. “Shwe” is the Burmese word for “gold”, and “dagon”, a derivative of “trihakumba” (contracted to “trikumba”, “tikun” and then “dagon”), means “three hills”.

The Shwedagon Pagoda was later built over the shrine containing the Buddha’s relics. Smaller pagodas, constructed with silver, tin, copper, lead, marble and iron brick, were built, one on top of the other, in the golden pagoda to enshrine the relics.

Night descends on the Shwedagon Pagoda.

Corrie Wingate/Apa Publications