The borders of Bago Division, the administrative region immediately north of Yangon, encompass a geography as varied as any in the country. To the east stretches the comparatively infertile 420km (260-mile) -long, Sittaung Valley; to the west is the broader, more lush and traditionally prosperous Ayeyarwady Valley, fed by annual deluges of silt from the Himalayas; while between the two sit the eroded slopes and depleted teak forests of the Bago Yoma Range. From the 12th century onwards, this vast expanse of jungle and alluvial plain formed the hinterland of Burma’s wealthiest and most powerful city, the port of Pegu, today known as Bago.

Shwemawdaw Pagoda, Bago.

Corrie Wingate/Apa Publications

Lynchpin of a trade network extending across the Indian Ocean and beyond, Pegu and its rulers, the Mon Kings, amassed wealth that attracted traders from all over the world, and also served as a magnet for rival surrounding kingdoms. Wars with the Burmese Taungoo dynasty, further north up the Sittaung Valley erupted repeatedly between the 16th and 18th centuries, resulting in the capture of Pegu by the rulers of Taungoo (who subsequently made it their own capital) and the eclipse of Mon culture and language throughout southern Burma.

Nowadays, the once-glorious city is little more than a provincial market town on the highway north, though it does retain a hoard of superb Buddhist monuments whose scale and splendour evoke the glory days of the Mon Kingdom. Lying only an hour-and-a-half by road from Yangon, it can easily be visited as a day trip, or as a stopover on the longer haul north to Mandalay via Taungoo, the old Burmese capital, with its splendid pagodas.

To the west, across the Bago Yoma hills, the town of Pyay (or Prome, as it was known in colonial times) on the Ayeyarwady River is the springboard for the ancient Pyu capital of Sri Ksetra, whose outlandish conical stupas, rising from the surrounding fields like the helmets of buried giants, are the last vestiges of a civilisation that thrived here between the 5th and 9th centuries.

A trishaw waiting outside Shwemawdaw Pagoda.

Corrie Wingate/Apa Publications

Bago

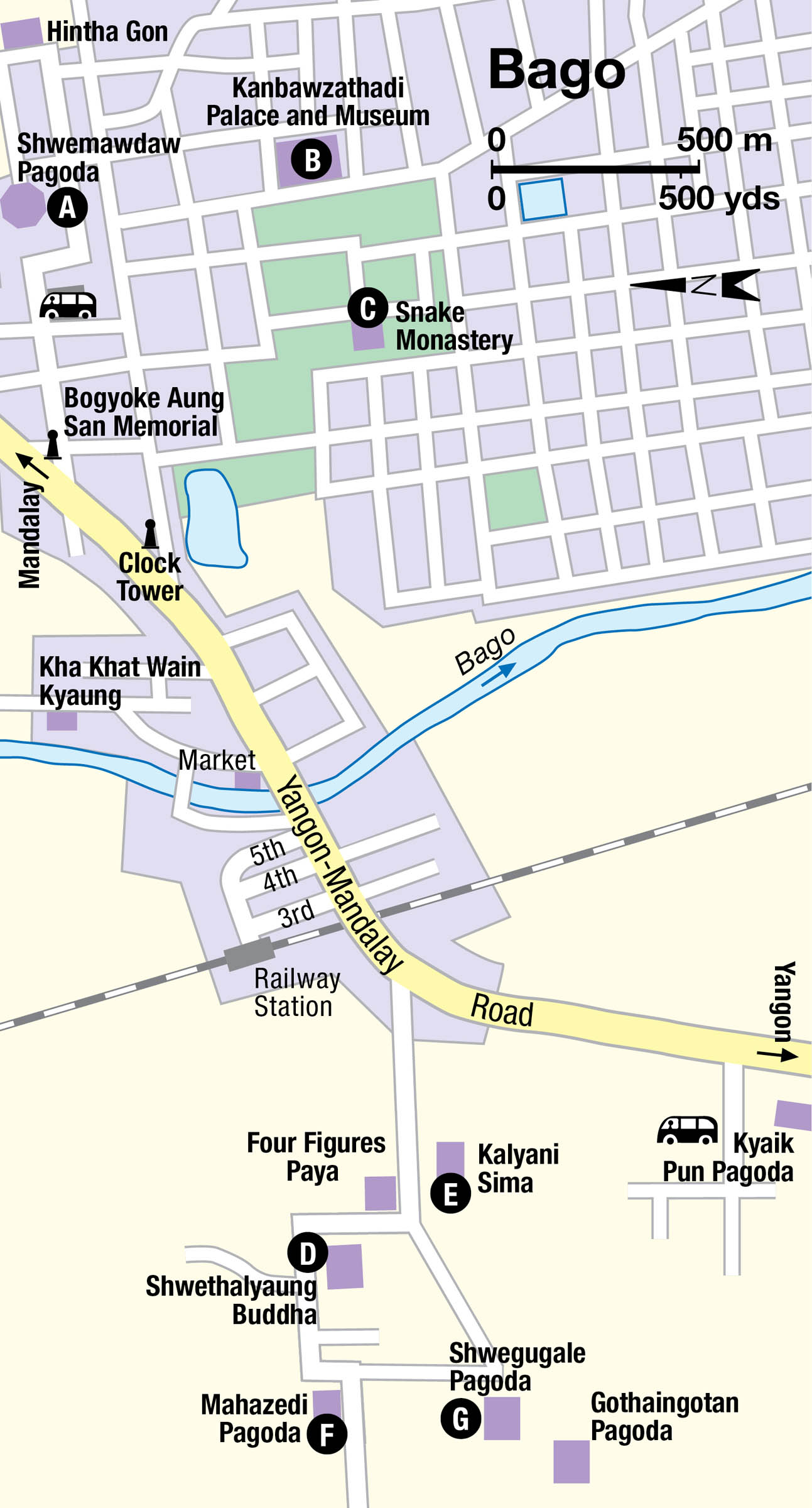

Bago 5 [map] – or “Pegu” as it was formerly known – retains an amazing concentration of temples, pagodas and giant Buddha statues for a town of its size – a legacy of its former prominence as Myanmar’s capital and major port under the Taungoo dynasty during parts of the 16th and 17th centuries. Most of these great religious monuments have been painstakingly maintained or restored, often with coats of vibrant gold leaf and modern paints that make them seem considerably less ancient than they actually are, but they are no less impressive for that. As the majority lie in, or within easy reach of, the town centre, you can comfortably get around them by trishaw or rented cycle. Note that foreigners are obliged to buy passes, on sale at the Shwemawdaw Pagoda, covering all of the sights in a single ticket (K10,000).

Situated around an hour-and-a-half by road (92km/57 miles) from Yangon, Bago makes an easy day trip, but its low-density feel also makes it an ideal first stop if you’re heading north.

The Shwethalyaung reclining Buddha.

Corrie Wingate/Apa Publications

History

Local lore suggests Bago dates back to AD 573, but most historians believe the city was founded in 825 by two brothers from Thaton, the then Mon capital. In 1057, King Anawrahta of Bagan conquered Thaton and the whole of southern Myanmar fell under Bamar sovereignty, a situation that continued for the next 250 years. In 1365, the Mon ruler King Byinnya-U, transferred the capital to Bago (known originally as Hanthawaddy or Hamsawaddy after its symbol, the hamsa, a mythological duck whose mate had to perch on his back).

Thus began the city’s golden age, which endured for nearly three centuries, epitomized by the great building works of the Hanthawaddy dynasty’s most famous rulers such as King Razadarit (1385–1425), Queen Shinsawpu (1453–72) and King Dhammazedi (1472–92).

In 1539 Bago was conquered by the ruler of the increasingly powerful Taungoo dynasty, King Tabinshwehti, who promptly selected it as his own new capital. His successor was the bellicose Bayinnaung, who extended the empire’s boundaries but drained the treasury with his military campaigns. He conquered Ayutthaya, capital of Siam, but was unable to leave a stable government in the subjugated region. Thus while Bago was one of the most splendid cities in the whole continent during this period, the country itself was reduced to poverty.

Bago remained capital of the Taungoo empire (with a couple of brief interruptions)until 1635, when the Taungoo capital was transferred to Inwa (Ava), near Mandalay. By this time Bago was already in decline, with silt deposits choking the harbour and preventing large vessels from docking, slowly strangling the city’s trade.

Bago remained under Taungoo rule for a further century until 1740, when the Mon finally cast off Bamar rule and (with Portugese and Dutch help) in 1752 even marched north and overran the old Taungoo capital of Ava, near Mandalay. Their success was short-lived, however. Just two years later King Alaungpaya of the newly established Konbaung Dynasty drove Mon forces out of Ava and chased them slowly south all the way back to Bago, which he eventually conquered and sacked in 1757 after a 14-month siege. The city, it is said, was taken at moonrise and the assembled Burmese population of starved men, women and children massacred “without distinction”. Alaungpaya then rode in to the city on elephant back, and ordered its walls and twenty gates razed to the ground.

Alaugpaya’s conquest marked the final end of Bago’s spell at the forefront of Burmese history, and also the demise of Myanmar’s last independent Mon kingdom. The city’s Mon inhabitants either fled to Thailand or intermarried with the victorious Bamar. Though King Bodawpaya (1782–1819) attempted to rebuild the city, partly due to the changing course of the Bago River, it never again approached its former greatness, and today only Bago’s many monuments serve as reminders of its glorious past.

Buddha statues and planetary prayer posts, Shwemawdaw Pagoda.

Corrie Wingate/Apa Publications

Shwemawdaw Pagoda and Hintha Gon

The most outstanding of Bago’s attractions is the Shwemawdaw Pagoda A [map] (Great Golden God Pagoda; daily; charge), which is to Bago what the Shwedagon is to Yangon. Its stupa can be seen from about 10km (6 miles) outside the city. Richly gilded from base to tip, the pagoda has many similarities to the Shwedagon and is in fact even taller than its more famous cousin, standing at 114 metres (374ft) in height.

The main stupa and pavilion at Shwemawdaw Pagoda.

Corrie Wingate/Apa Publications

Legend has it that two merchant brothers, Mahasala and Kullasala, returned from India with two hairs given to them by Gautama Buddha. They built a small stupa over the relics, and in the following years, this shrine was enlarged several times, with sacred teeth added to the collection of relics in 982 and 1385. King Dhammazedi installed a bell on the pagoda’s main platform, which he had inscribed with runes that can still be seen, indecipherable though they are.

In the 16th century, King Bayinnaung gave the jewels from his crown to make a hti (jewelled umbrella) for the pagoda, and in 1796, King Bodawpaya donated a new umbrella and raised the height of the pagoda to 90 metres (295ft). In the 20th century, the Shwemawdaw was hit by three serious earthquakes, the last of which, in 1930, almost completely destroyed it. After World War II, however, the pagoda was rebuilt by unpaid volunteers with the proceeds of popular donations to stand higher than ever. In 1954, it got a new diamond-studded hti.

As at Yangon’s Shwedagon Pagoda, the Shwemawdaw’s main terrace can be approached from four directions by covered stairways, each like a miniature bazaar, with shops selling everything from medicinal herbs to monastic offerings for sale. All four stairways are guarded by huge white chinthe holding a sitting Buddha in its mouth. Faded murals along the main entrance steps recall the 1930 quake destruction and the pagoda’s later reconstruction.

The terrace itself it lined with a string of brightly coloured tazaung (pavilions), as well as the usual eight planetary prayer posts found in many larger Burmese pagodas along with statues of various nat spirits. It’s also worth having a look at the small museum containing some ancient wooden and bronze Buddha figures salvaged from the ruins of the 1930 earthquake.

Admiring Shwemawdaw Pagoda.

Corrie Wingate/Apa Publications

On a hilltop just to the east, reached via a flight of steps beginning opposite the main entrance to the Shwemawdaw Pagoda, lie the ruins of a more ancient stupa – the Hintha Gon. In front of the stupa stands a statue of a pair of hamsa, the mythological birds associated with the foundation of Bago. Geologists suspect that the hill was at one time an island in the Gulf of Mottama, and may thus have been the spot where the hamsa were believed to have landed (hamsa are also known as hintha – hence the name, meaning “Hamsa Hill”). A high-roofed platform atop the hill provides a good view of the surrounding countryside.

Kanbawza Thadi Palace.

Bigstock

Kanbawzathadi Palace

The area to the south of the Shwemawdaw Pagoda and Hintha Gon is believed to have been the site of the original Mon city of Hanthawady, where Bayinnaung subsequently erected his palace in 1553. Destroyed only fifty years later, the lavish complex of 76 buildings lay forgotten until 1990, when archaeologists uncovered a series of huge post holes and teak pillars beneath half a dozen mounds of brick and soil. Together with 16th-century drawings, these provided the blueprint for a massive restoration programme initiated by the Burmese military government.

At its centre is a shoddily built “replica” of Bayinnaung’s Kanbawzathadi Palace B [map] (daily 9am–5pm), featuring a gilded Lion Throne Room, Settaw Saung and Queen’s Bee Hall, complete with spray-stencilled decor. Quite how closely they resemble the originals is anyone’s guess, but the buildings do at least hint at the extraordinary wealth and sophistication of the Taungoo dynasty during its heyday. A small museum on the site houses the huge pillars and other artefacts discovered by archaeologists during the excavations of the 1990s.

The Snake Monastery

A couple of blocks southwest of the Kanbawzathadi Palace is Bago quirky Snake Monastery C [map], home to a giant Burmese python which is said to be the reincarnation of a Buddhist abbot from Hsipaw. Pilgrims and tourists file through year round to pay their respects to the snake, which measures a whopping 5 metres (17ft) from head to tail and is now thought to be well over a century old.

Frieze behind the Shwethalyaung reclining Buddha depicting King Migadippa and the making of the statue.

Corrie Wingate/Apa Publications

The Shwethalyaung Buddha

The rest of Bago’s monuments lie on the opposite, western side of town. Foremost among them is the Shwethalyaung Buddha D [map], which is said to depict Gautama on the eve of his entering nibbana (nirvana). Revered throughout Myanmar as the country’s most beautiful reclining Buddha, the statue measures 55 metres (180ft) in length and 16 metres (52ft) in height. It is not quite as large as Yangon’s more recent Kyauk Htat Gyi (built in the 1960s) but, as a result of its quality and long history, is much the better-known and loved of the two.

The statue was left to decay for nearly 500 years until it was restored during Dhammazedi’s reign. In the centuries that followed, Bago was destroyed twice, and by the 18th century the Shwethalyaung Buddha had become lost beneath countless layers of tropical vegetation. It was only in 1881 that a group of contractors who were building a railway for the British stumbled across it. In 1906, after the undergrowth had been cleared away, an iron tazaung was erected over the Buddha, which protects it from the elements, although it does somewhat detract from the view of the statue inside. The Buddha was most recently renovated in 1948, when it was re-gilded and painted.

Kalyani Sima

To the south of the Shwethalyaung Buddha stands the Kalyani Sima E [map] ordination hall, built by King Dhammazedi in 1476 with the aim of rejuvenating the Burmese sangha (monkhood). When the unity of Buddhism in Burma was threatened by schisms following the downfall of the Bagan Empire, Dhammazedi dispatched 22 monks to Ceylon (now Sri Lanka), a stronghold of the Theravada Buddhist faith. The monks were ordained by the Kalyani River (now known as the Kelani River, near present-day Colombo) in Ceylon (now Sri Lanka). Upon their return to Burma after surviving a shipwreck, Dhammazedi built the Kalyani Sima, which he named after the Ceylonese river.

To the west of the hall, 10 tablets provide a detailed history of Buddhism in the region and of the country’s 15th-century trade with Ceylon and south India. Three of the stones are inscribed in Pali, seven in Mon. Although some of the tablets are shattered and others are illegible in places, the complete text has been preserved on palm-leaf copies.

The Kalyani Sima, which served as a model for nearly 400 other sima built by Dhammazedi, did not escape the ravages of the Mon’s aggressive politics – or indeed the hostility of other ambitious kingdoms. The Portuguese adventurer de Brito destroyed it in 1599, and Alaungpaya razed the reconstructed hall when he sacked Bago in 1757. The structure collapsed following the earthquake of 1930, but, once rebuilt 24 years later, it was rededicated to its original purpose at a ceremony attended by U Nu. Today, the monks live in lodgings around the sima, set today amid peaceful, leafy grounds.

The Mahazedi Pagoda and around

The Mahazedi Pagoda F [map], to the west of the Shwethalyaung Buddha, is famous in Myanmar as the place where King Bayinnaung enshrined a gold- and jewel-encrusted tooth of the Buddha to confirm the divine approval of his reign. He acquired it from the King of Kandy in Ceylon on the understanding that it was the original, and much revered, Buddha’s Tooth, but the relic turned out to be nothing of the kind.

Undeterred, Bayinnaung locked the tooth away in the Mahazedi Pagoda, where it remained until 1599, when Anaukhpetlun transferred it to his capital, Taungoo. A short time later, King Thalun built the Kaunghmudaw Pagoda in nearby Sagaing to house the relic, where it can still be seen today. The Mahazedi Pagoda was destroyed during Alaungpaya’s time, and levelled again by the 1930 earthquake. With the reconstruction work recently completed, the uppermost walkway around the stupa affords a marvellous view of the surrounding plain.

The four seated Buddha statues of Kyaikpun Pagoda.

Corrie Wingate/Apa Publications

A short distance west of the Mahazedi, on the outskirts of town, stands the Shwegugale Pagoda G [map], in which 64 Buddha figures sit in a circle in a gloomy vault around the central stupa. About 1.5km (1 mile) further south, you’ll find the Kyaik Pun Pagoda. Built by Dhammazedi in 1476, it consists of four Buddha figures, each 30 metres (98ft) tall, seated back to back against a square pillar facing the four cardinal points.

Taungoo

Until the construction of Naypyidaw in 2005, Taungoo 6 [map] was the largest city in the Sittaung Valley and still sees a handful of travellers stopping over for a night or two en route between Yangon and Mandalay. It’s best known in Myanmar as the home seat of the powerful Taungo dynasty whose rule spanned 150 years and seven kings (although most of the dynasty’s later rulers based themselves in Bago, and later in Ava, near Mandalay, rather than in Taungoo itself). Relatively few monuments survive from Taungoo’s glory days, however, the royal palace having fallen prey to Japanese bombers during World War II.

The one outstanding historic sight that the town retains is the Shwesandaw Pagoda, which attracts streams of pilgrims year-round. Foreign visitors also use Taungoo as a springboard for trips into the jungle-covered Bago Yoma Range, to the northwest. Teak and other hardwoods harvested in these ancient forests have formed the mainstay of the local economy for decades; elephants are still extensively used to extract timber. With a little forward planning, it’s possible to see tuskers at work at logging camps around Karen villages in the surrounding countryside.

Tip

All Taungoo’s attractions are concentrated in the city centre and are easily explored either on foot, or by hiring a trishaw for a couple of hours.

Taungoo’s pagodas

The focal point of Taungoo’s Shwesandaw Pagoda, in the centre of the town, is its gilded bell-shaped stupa, built in 1597 on the site of a much more ancient one believed to have contained sacred relics of the Buddha. Statues of the seven Taungoo kings stand in the precinct surrounding the monument; one of the nearby shrines houses a reclining Buddha attended by various devas, while another shelters a sitting Buddha 3.6 metres (11ft) tall. This latter icon was donated by a devotee in 1912, who gave the equivalent of his weight in bronze and silver to cast the statue, and whose ashes have been interred behind it.

A two-minute stroll south of the Shwesandaw Pagoda takes you to Taungoo’s second pagoda, the Myasigon, a modern structure centered on a gilded stupa. Facing it are two Chinese images of goddesses, one seated on an elephant, the other on a Fu dog, which were gifts from a visiting German Buddhist in 1901. The adjacent museum features a three-headed bronze elephant, the Erawan, believed to have been Indra’s mount and rubbed to a brilliant sheen by worshippers, as well as a standing Buddha taken from the Siamese by King Bayinnaung and two 19th-century British cannons.

West of here, the fine Kandawgyi (“Royal”) Lake provides another memento of Taungoo’s illustrious past, as do the slight remains of a moat and various gateways which can still be made out in various places around the centre of town.

Elephants at work

Elephants are used in Myanmar to haul logs felled in the forest to the nearest main road to await transport by truck. The distances the beasts of burden have to cover can be lengthy if the log has been felled in a remote area.

An elephant can carry only one heavy log at a time, using its trunk to move it, guided by an oozie (Burmese for “mahout”) who rides on its back with his pejeik, or apprentice.

The elephants are amply rewarded with lots of fodder, and at night after work, they are released into the forest, free to roam and to forage for their own food. Every morning, they are rounded up by their personal oozie who will make special calls, to which only their particular elephants will respond. They are then bathed and harnessed, ready for another day’s work, which is usually limited to five hours.

Elephants start timber-working from the age of five, once they are independent of their mother. They are given transport duties until they are 16, followed by light extraction work, until they grow in strength at the age of 24. The elephants are in their prime in their thirties and generally work until they turn 53, at which age they are gradually retired.

Elephants camps

A fascinating trip (most easily arranged through the Myanmar Beauty guesthouse in Taungoo) is the trip over rutted timber trails into the Bago Yoma hills to watch elephants at work in one of the area’s logging or forest camps. You can travel there and back in a day, although you may be able to arrange overnight trips, spending a night in a Karen village deep in the forest en route, if you give sufficient advance notice (a few days’ notice is advisable even if you only want to do the day trip; two weeks or so is best for longer trips).

A visit to one of the elephant lgging camps can potentially be combined with the cross-country journey from Taungoo to Pyay. An unsurfaced logging track connects the town of Oktwin, 9km (5.5 miles) south of Taungoo, with Pyay in the Ayeyarwady Valley, via a string of Karen villages. Passing through 62km (38.5 miles) of wild country the route is not open to independent travellers, although foreigners may follow it on pre-arranged tours in 4-wheel-drive vehicles. Aside from the beauty of the scenery, the great thing about this road is that it cuts across the Bago Yoma range separating the Sittaung and Ayeyarwady valleys, enabling travellers to make a time-saving short cut to Pyay.

Wheeling merchandise through through Pyay City Market.

Getty Images

Pyay

Now the seventh largest city in Myanmar, with a population of around a quarter of a million, modern Pyay 7 [map] – (or “Prome” as it was known to the British) developed in colonial times as a major transhipment port for river traffic travelling between Mandalay and Yangon. The magnificent Shwesandaw Pagoda rising from its midst, however, points to the town’s much older roots. These date back to the 5th century or earlier, when the ancient city of Sri Ksetra – or Thayekhittaya as it’s now known – was established here, becoming the largest of the ancient Pyu city states which dominated trade along the Ayeyarwady between India and Chinafrom the 5th to 9th centuries AD.

While the great gilded pagoda and archaeological site on the outskirts are undeniably Pyay’s stand-out attractions, the town itself makes a very pleasant place to break the long trek between Yangon and Mandalay, with lively market squares and a waterfront full of Burmese atmosphere.

Crowning a low hill to the southeast of the town centre, Pyay’s Shwesandaw Pagoda is one of Myanmar’s largest gilded stupas, topping out at a full metre taller than the Shwedagon in Yangon. Its mesmerising form, soaring like a giant rocket above the tin-rooftops and palms below, is reason enough to take time out of the trip to or from Bagan. Come at sunset, when the rich evening light turns the gold leaf a magical colour and the river to the west glows molten orange, for the full effect.

Although its origins are believed to date from 589 BC, the Shwesandaw was enlarged and rebuilt several times by conquering kings, notably Kyanzittha of Bagan in AD 1083, who also commissioned a series of stone inscriptions detailing the pagoda’s history. These are now housed in a brick building on the northeast side of the precinct. It was Alaungpaya, however, who gilded the stupa in 1754, and who added a second hti to the finial – a feature unique to this paya, and which – somewhat ironically – the king hoped would symbolise the “unity of the Burmese people” after his brutal sack of the town.

Looking east from the Shwesandaw, it’s impossible to miss the mighty seated Buddha, or Sehtatgyi Paya, whose head rises to almost the same height as the great pagoda. Most visitors content themselves with this view of the giant, but the terrace encircling the statue makes a dramatic spot from which to view the Shwesandaw at sunrise.

Sri Ksetra (Thayekhittaya)

The remains of ancient Sri Ksetra 8 [map] now better known as Thayekhittaya – are dotted around the village of Hmawza, 8km (5 miles) east of Pyay. Between the 4th and 9th centuries, this was the largest of numerous walled city states founded by the Pyu people, whose kings controlled river-borne trade up and down the Ayeyarwady and out to the open sea to India, from where they drew much of their religious and cultural inspiration.

Three distinct dynasties ruled at Sri Ksetra (from the Sanskrit for “City of Splendour”) before their capital fell under the sway of Bagan in the 10th century. Absorbing influences from southwest as well as southeast India, its rulers erected an impressive array of brick-built stupas, palaces and monasteries, encircled by moats and walls whose vestiges are still clearly visible. At its peak twelve centuries ago, the city was the largest and grandest fortified settlement in Asia: 46 sq km (18 sq miles) of land lay behind its ramparts, with most of the buildings grouped on the south side of the site, and fields to the north (ensuring food supplies were protected in times of siege).

Contemporary Chinese chronicles talked of Sri Ksetra’s brilliance: “The city wall, faced with green-glazed brick, is 600 lines in circumference and has 12 gates and pagodas at each of the four corners. Within are more than 1,000 monks, all resplendent with gold, silver and cinnabar. The women wear their hair in a top knot ornamented with flowers, pearls and precious stones, and are trained in music and dance.”

Whether invasions by the Mons or the silting up of the Ayeyarwady Delta were responsible for Sri Ksetra’s gradual decline, no one is absolutely sure, but by the 10th century the capital provided easy pickings for Bagan’s army. Today, only the massive, cylindrical brick stupas, now incongruously stranded amidst tranquil fields still give a real sense of the city’s former grandeur. None approaches the scale and drama of those at Bagan, but their great antiquity and the site’s sleepy, rural feel make for a memorable half day’s exploration.

Tip

The easiest way to get around the sandy tracks threading through the ruins (daily 9am–4pm; charge) is by ox-cart; local drivers appear on arrival at the entrance.

You’re permitted to walk around the site, but there’s precious little shade and the heat can be infernal. Cycles are forbidden. Foreigners have to purchase a $5 entry ticket; the warden will also encourage you to buy another $5 ticket for the site museum, but its poorly displayed, desultory collection of votive terracottas, funerary urns and coins doesn’t merit the expense, and most of the prize finds dug up here having been taken to London (where many remain on show at the Victoria & Albert Museum) or the National Museum in Yangon.

Approaching via the main road in the north, the first of the large pagodas you pass is the helmet-shaped Payagyi. Dating from the 4th century AD, it’s Myanmar’s oldest intact stupa – though renovation work has been carried out to its exterior and a golden hti added on top. Further west, just beyond the turning to the site, the equally striking Payamar Pagoda is an exact contemporary of the Payagyi, which local tradition holds enshrines a finger, collar bone and toenail of the Buddha.

Heading further south still from here, through Hmawza village and past its tiny train station, cart drivers make for the vestiges of the Old Palace, scattered over a rectangular enclosure, before striking out across the fields towards the main concentration of monuments beyond the Rahanta Gate. Once clear of the earthworks where the city’s southwestern entrance, the Rahanda (or Yahanda) Gate, would once have stood, you approach the tiny Rahanda Pagoda, a narrow shrine housing seven sitting Buddhas (there would originally have been eight). Skirting Rahanda Lake, you then come to the site’s most famous monument, the 46-metre (150ft) -tall Baw Baw Gyi Pagoda, which dates from the 5th century and served as the prototype for most of Myanmar’s ancient stupas. A couple of hundred metres to its east, the Bei Bei Pagoda is a square structure surmounted by three terraces from which an undecorated, round-topped tower rises. Inside it, statues of the Buddha and two of his great disciples peer out of the gloom; look for the ancient Pyu inscriptions on their bases.

The spectacled Buddha at the Shwemyetman Pagoda in Shwedaung.

Fotolia

Shwedaung

A popular stop on the Ayeyarwady Valley’s pilgrimage trail is the Shwemyetman Pagoda at Shwedaung 9 [map], 14km (9 miles) south of Pyay on the main Yangon highway, whose central shrine encloses a laquerware Buddha famous as the only one in Myanmar to wear gold-rimmed spectacles (myetman). Local legend asserts that the original pair were a gift of King Duttabaung in the 4th century AD after the monarch lost his sight. The unconventional donation brought about a dramatic recovery, and once news of his miraculous cure spread across the country, worshippers began to pour in. However, thieves have repeatedly stolen the famous specs, and replacement pairs have had to be made on several occasions, including once in the colonial era when the local deputy commissioner, a Mr Hurtno, donated a set of gold-rimmed glasses to the temple to cure his wife’s blindness.