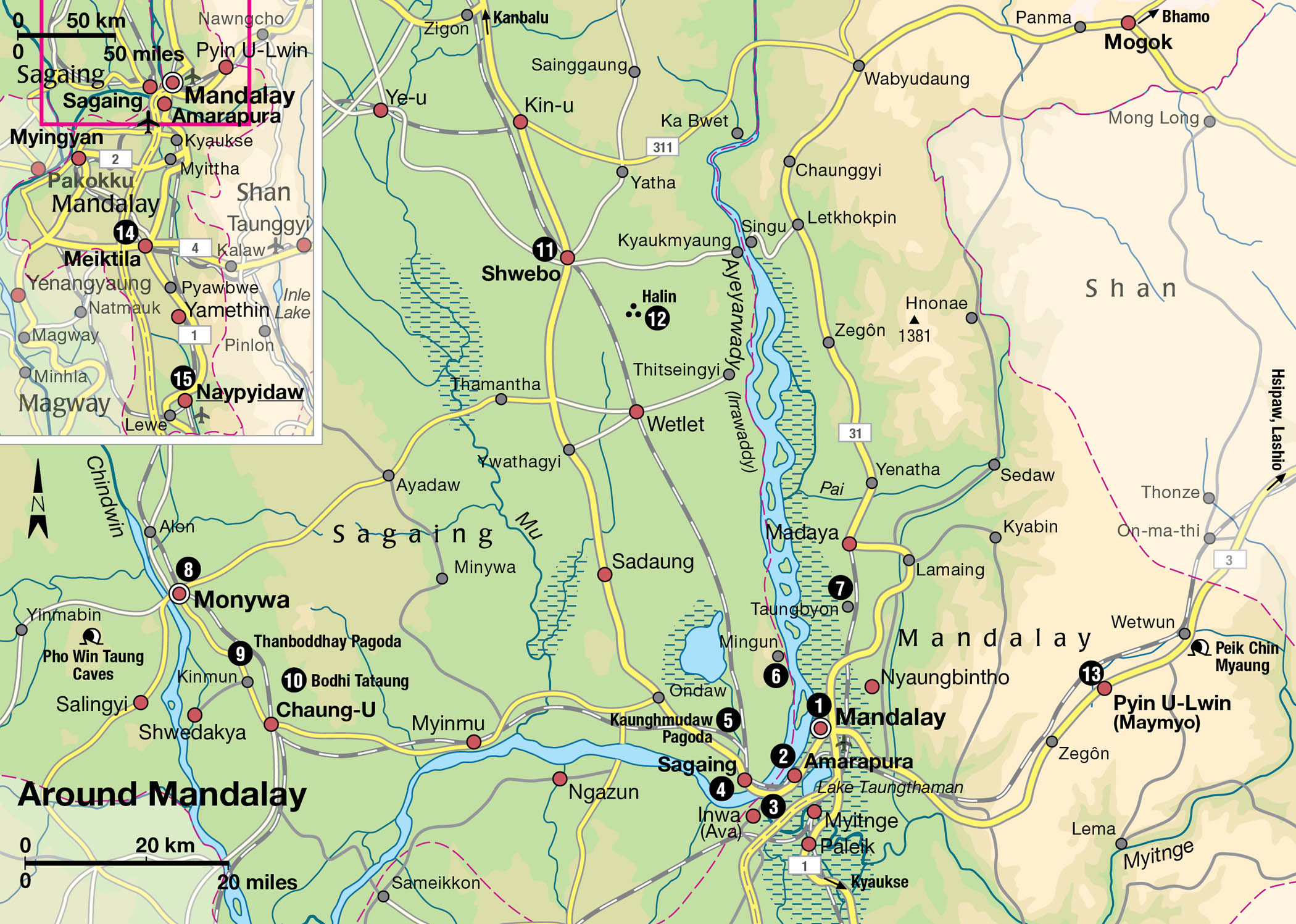

For the majority of visitors to Mandalay 1 [map], the attractions of the modern city pale next to the wonders hidden in the surrounding countryside. Clustered along the banks of the Ayeyarwady, amid the vestiges of former capitals and ancient pilgrimage places, are some of Myanmar’s most iconic sights: the famous U Bein’s Bridge, the teak causeway along which streams of villagers and red-robed monks file each morning and evening; the exquisitely carved wooden monastery at Inwa; and the vast, red-brick cube of Bodawpaya’s unfinished stupa at Mingun.

A nun prays at U Min Thonze Pagoda, Sagaing.

Corrie Wingate/Apa Publications

These alone hold enough interest to fill two or three days of sightseeing. But with a little more time you could make a foray west to the market town of Monywa, springboard for another crop of amazing Theravada sites: the ornate Thanboddhay temple, where more than half a million Buddha images are enshrined amid a forest of multicoloured stupas; a medieval cave complex hewn from solid rock at Hpo Win Tang; and a pair of gargantuan Buddha images – one standing, one reclining – rising from a hilltop at Bodhi Tataung.

After touring the bumpy back roads and rivers of Mandalay’s hinterland, you’ll be more than ready for a respite from the heat, and the hill station of Pyin U-Lwin, on the fringes of the Shan Plateau a day’s journey northeast of the city, provides the perfect setting for a recuperative spell away from the plains, just as it did for the British burrasahibs who founded the town in the 19th century.

On Taungthaman Lake, Amarapura.

Corrie Wingate/Apa Publications

Finally, further highlights await heading south down the Sittaung Valley to Yangon, including the attractive town of Meiktila with its lakeside temples and shrines and the sprawling modern capital of Naypyidaw – a bizarre monument to the megalomania and bombast of the country’s ruling generals.

Amarapura

Founded by Bodawpaya in 1782, Amarapura 2 [map] – “City of Immortality” – is the youngest of the royal capitals near Mandalay. It replaced Inwa (Ava), an hour’s walk southwest, on the advice of royal astrologers, who were concerned about the bloody way in which the king had ascended to the throne. In May 1783, the court and entire population duly packed up their belongings and shifted to land allocated to them around a newly built palace, surrounded by a wall 1.6km (1 mile) in circumference, with a pagoda standing at each of its four corners. The site, however, would be occupied for less than 70 years. In 1857, King Mindon dismantled the royal enclave and transported it to a completely new location, 11km (7miles) further north at the foot of Mandalay Hill.

Today a town of 10,000 inhabitants, the former capital has almost merged with the southern fringes of greater Mandalay, but still preserves a markedly different feel to the big city, with streets draped around the leafy shores of a shallow lake. Many of Amarapura’s families are engaged in the silk industry, weaving the exquisite acheik htamein (ceremonial longyis) worn on special occasions by Burmese women. Every second house seems to hold a weaver’s workshop, and the clickety-clack of looms forms a constant soundtrack as you stroll around. Amarapura’s other traditional industry is bronze casting: cymbals, gongs and images of the Buddha are made here out of a special alloy of bronze and lead.

With U Bein’s Bridge at the far southern end of town and most of the other points of interest grouped around the north, you’ll need a taxi or bicycle to get around the sights if travelling independently. Come early in the morning or late in the afternoon to avoid the large tour groups: Amarapura and its teak bridge get swamped in peak season.

Tip

You can travel across Lake Taungthaman one way by oar-powered gondola to the Kyauktawgyi Pagoda, then return by walking over U Bein’s Bridge to get a perspective of the lake’s size. Sunset is a good time to cross the bridge for the views.

Amarapura’s main sights

Today, virtually nothing remains of the former Royal Palace, situated to the east of Amarapura’s centre (between a military base and timber yard). Some of the wooden buildings were reconstructed in Mandalay by Mindon, while the walls that were left standing were used by the British as a source of cheap material for roads and railways. The four pagodas which once marked the corners of the city wall, however, can still be seen, as can two stone buildings – the treasury and the old watchtower. The graves of Bodawpaya and Bagyidaw also survive.

In the southern part of town sits the well-preserved Patodawgyi Pagoda, built by King Bagyidaw in 1820. A bell-shaped stupa, it stands on five terraces which are covered with Jataka reliefs. An inscription stone nearby tells the story of the construction of the pagoda.

Amarapura also holds one of the largest monasteries in Myanmar. The presence of up to 1,200 monks (during the Buddhist Lent) in the Mahagandhayon Monastery contributes to the religious atmosphere of the city. Visitors are welcome and it is a spectacular sight to witness the hundreds of monks lining up for their one daily meal every morning at 11am – though don’t expect to be alone. Bus loads of foreigners descend on the refectory to photograph the spectacle.

Crossing Taungthaman lake by boat, U Bein bridge in background.

Corrie Wingate/Apa Publications

U Bein’s Bridge

To the south of Amarapura lies Lake Taungthaman, a seasonal body of water which dries up in the winter and leaves fertile, arable land in its wake. It is spanned by the 1.2km (0.7-mile) -long U Bein’s Bridge, constructed from the teak planks of Inwa by King Bodawpaya’s mayor (U Bein) following the move to Amarapura. Little altered in two centuries, it takes 15 minutes to cross on foot. The best time to view the bridge is early in the morning, when hundreds of locals – from farmers and market stallholders to groups of monks – plod over it, to the delight of the bus parties of foreign tourists who turn up in droves at the little boat jetty on the far western side, where they’re met by crowds of gee-gaw and postcard sellers. You can, however, bypass the crowds by starting your visit from the far, eastern side. Tea stalls dotted along the bridge provide much-needed shade and sustenance.

Crossing U Bein bridge.

Corrie Wingate/Apa Publications

Kyauktawgyi Pagoda

In the middle of a widely scattered village on the east side of U Bein’s Bridge is the Kyauktawgyi Pagoda, built by King Pagan in 1847. Like the Kyauktawgyi in Mandalay, it was intended to be a replica of Bagan’s Ananda Temple. Inside, an enormous Buddha made of pale-green Sagyin marble dominates the central shrine.

Kyauktawgyi Pagoda, Amarapura.

Corrie Wingate/Apa Publications

In the same chamber stand 88 statues of the Buddha’s disciples, as well as 12 manussa, mythical half-man/half-beast beings. The temple’s east and west entrances are decorated with murals depicting the daily life of the Burmese at the time of the pagoda’s construction. If you look carefully you may be able to make out European faces among the paintings.

The area surrounding the Kyauktawgyi Pagoda is full of smaller pagodas in various stages of decay. These temples have been systematically plundered ever since the prices of ancient Burmese artefacts reached astronomical levels in the antique shops of Bangkok. On Amarapura’s Ayeyarwady bank, 30 minutes’ walk away from Amarapura’s main street, stand two white pagodas – the Shwe-kyet-yet Pagoda and the Shwe-kyet-kya Pagoda – fronted by a pair of carved lions. Both date from the 12th century. A short distance downriver, King Mindon’s Thanbyedan Fort was designed in European style by French and Italian advisors. The bastion was intended to stop hostile armies from attacking with warships from the Ayeyarwady. Yet when the British invaded Mandalay in 1885 in exactly this way, not a shot was fired – the Burmese, lacking strong armed forces, had already given up.

Paleik

A visit to Amarapura (or indeed Inwa) can also be combined with a side-trip to village of Paleik, a further 8km south. The village is famous for its celebrated Snake Temple (Hmwe Paya), home to a small menagerie of pythons. The temple’s original two pythons were found wrapped around a Buddha statue in an old pagoda here in 1974. The snakes were removed, but continued to return on subsequent days. Eventually, the pythons’ persistence persuaded local monks that they must be holy (perhaps the reincarnated souls of former monks), and the snakes were allowed them to stay unmolested, with a new temple being constructed around their abode.

The original pythons are now dead (although their taxidermied remains can still be seen) but further pampered pythons, donated to the temple by well-wishers, continue to live here. Most people visit at 11am, when the snakes receive their daily wash in a petal-filled bath.

Inwa (Ava)

The city of Inwa 3 [map], known in British times as “Ava” but by its former inhabitants as “Ratnapura” (“City of Gems”), was founded in 1364 by King Thadominbya, and later served as the capital of the Konbaung dynasty. Numerous vestiges of its former prominence survive, including a magnificent teak monastery, marooned amid empty fields and grassy expanses on the banks of the Ayeyarwady. You can drive there overland, but most visitors, including nearly all tour groups, opt to arrive by boat via a short crossing of the Myitnge River bounding the east of the site, where you transfer to a horse-cart for the leisurely tour of the ruins. It’s a great way to see the monuments, and makes a relaxing change after the frenzy of central Mandalay.

Guide at Tojang Paya, Inwa.

Corrie Wingate/Apa Publications

Fact

In the vicinity of the Maha Aungmye Bonzan Monastery is the Adoniram Judson Memorial. Judson, an American missionary who compiled the first Anglo-Burmese dictionary, was jailed during the First Anglo-Burmese War and endured severe torture during his imprisonment. He had mistakenly assumed that the Burmese would distinguish between British colonialists and American missionaries.

Treelined road on the way to Inwa

Corrie Wingate/Apa Publications

Unlike most of Myanmar’s other royal cities, Inwa’s city wall was not square, but shaped like a sitting lion, such as those found in front of large pagodas. Only a part of the wall still stands; the most complete section is at the north gate (near the horse-cart rank and jetty), known as Gaung Say Daga, or “gate of the hair-washing ceremony”. Every April during the Thingyan Festival, this ritual hair-washing takes place as a purification rite to welcome the king of the nat. Today, the ritual is performed only in homes, but in imperial times even the king washed his hair at this spot.

Near the north gate are the ruins of the Nanmyin Watchtower, the so-called “leaning tower of Inwa”. All that remains of Bagyidaw’s palace, this erstwhile 27-metre (89ft) lookout was damaged so heavily by an 1838 earthquake that its upper portion collapsed. Shortly afterwards, the construction began to lean to one side due to the earth sinking beneath it.

Not far from the “leaning tower” is the best preserved of all buildings in Inwa, the Maha Aungmye Bonzan Monastery. Also known as the Ok Kyaung, the tall, stucco-decorated brick structure dates from 1818 and was conceived in the same style as that of more common teak kyaung (monastery); yet its masonry guaranteed that it would survive longer than its wooden cousins. In the middle of the monastery is a statue of the Buddha, placed on a pedestal trimmed with glass mosaic. Beside the entrance archway stands an old marble plaque which tells, in English, the story of an American missionary’s Burmese wife who was a staunch convert to Christianity until her death during the First Anglo-Burmese War. Next door to the kyaung is a seven-tiered prayer hall, which suffered heavy damage in the 1838 earthquake, but was repaired in 1873 by Hsinbyumashin, the daughter of Nanmadaw Me Nu.

Numerous pagodas are scattered around the outlying areas of the site. Among the most interesting is the Htilaingshin Paya, built by King Kyanzittha during the Bagan era. Other important shrines include the four-storey Le-Htat-Gyi Pagoda and the Lawkatharaphy Pagoda, both in the southern part of the former city. Some 1.5km (1 mile) south of the site stands Inwa Fort, once considered part of the “unconquerable triangle”, which included the Thanbyedan and Sagaing citadels.

Teaching novice monks at Bagaya Kyaung, Inwa.

Corrie Wingate/Apa Publications

Bagaya Kyaung

Inwa’s single most impressive building, however, is the beautiful Bagaya Kyaung, a cavernous, ornately carved teak monastery which, despite its relatively well-preserved appearance, is considerably older than its masonry counterpart to the northeast. It dates from 1593 and once formed the far southern corner of the royal enclave, close to the confluence of the Ayeyarwady and Myitinge rivers. The kyaung is famous, above all, for its traditional woodcarving. Doorways, window surrounds, partitions and pillar bases are all richly carved in high Burmese style, combining floral arabesques with reliefs of birds, animals and figures from Buddhist mythology. Enlivening the gloomy and dusty interior, the only splashes of colour are a sumptuously glass-inlaid, lacquered trunk, and the presiding Buddha image itself, which sports a coat of gold leaf. A total of 267 massive pillars support the building, whose seven storeys denote its former royal status. A modern working monastery stands next door.

Forty-five Buddhas line the crescent-shaped grotto at U Min Thonze Pagoda, Sagaing.

Corrie Wingate/Apa Publications

Sagaing

One of the most serene spectacles Southeast Asia has to offer is the vision of Sagaing Hill 4 [map] at sunrise, its countless stupas, spires and temple towers glowing gold and pale-crimson above the dark, silty water of the Ayeywarwady. Although invisible from the far banks, a maze of stepped walkways and colonnades threads around these other-worldly monuments, swathed in palms, frangipani, tamarind and mango bushes.

The view across the Ayeyarwady from Sun U Ponya Shin Pagoda, Sagaing.

Corrie Wingate/Apa Publications

Around 5,000 monks live amid Sagaing’s Arcadian landscape, in 600 monasteries and a township of private homes scattered over a tangle of valleys and ridgetops. For Burmese Buddhists, this is sacred ground: “the foothill of Mount Meeru”. Refugees from the city retreat here – for a day or a lifetime – to meditate; devout families bring their young sons to undergo the shin pyu ceremony, consigning their loved ones to a period of monastic life. From before dawn until well after dusk, rows of monks file around the lanes, and cymbals, gongs and pagoda bells echo between the whitewashed buildings, as they have for centuries.

Sagaing’s unique atmosphere ensures it features prominently on Myanmar’s tourist trail, as well as the Buddhist pilgrimage circuit. You can get there by ferry from Inwa, or via the road bridge. Jeep taxis and horse-carts are on hand to shuttle visitors from the flat town centre to the monastery-studded hilltop behind, or you can walk, improvising a route up the stepped paths.

Sagaing’s pagodas

Whatever your means of transport, you’ll probably be dropped on Sagaing Hill outside Sagaing’s most famous landmark, the Sun U Ponya Shin Pagoda, a favourite viewpoint for photographers and an important religious site centred on a huge gilded stupa. The monument dates from the early 14th century when the city was first established as the seat of the Sagaing kings, one of the dynasties to emerge after the demise of Bagan. After their decline, Sagaing became a fiefdom of the princes of Ava, but rose to be a capital once again in the three-year reign of King Naundawgyi, beginning in 1760. A terrace to the rear of the pagoda affords superb views across the river to Mandalay.

Also on Sagaing Hill it’s worth hunting out the U Min Thonze Pagoda, a twenty-minute walk north of the Sun U Ponya Shin, where 45 Buddha images gaze from a crescent-shaped grotto, against a backdrop of superbly elaborate red and turquoise glass mosaic. Among the traditional handicraft stalls at the bottom of the steps leading to it, look out for ones specialising in bags made from stitched watermelon seeds. Sagaing’s other monuments are scattered over a wide area and, if you’re not on a pre-arranged tour, you’ll need a horse-cart or taxi to get around the highlights.

At the far, south end of town not far from the old Ava Bridge, the Htupayon Pagoda – built by King Barapati in 1444 – was destroyed by the 1838 earthquake, and King Pagan, who wanted to have it rebuilt, was dethroned before repairs were completed. The 30-metre (98ft) -high base is still standing, however, and represents a rare style of temple architecture in Myanmar.

The Aungmyelawka Pagoda, built by King Bodawpaya in 1783 on the Ayeyarwady riverfront near the Htupayon Pagoda, is a sandstone replica of the Shwezigon Pagoda in Nyaung U. Bodawpaya had it built to balance the “necessary cruelties” of his reign and improve his merit for future incarnations.

Sun U Ponya Shin Pagoda, Sagaing.

Corrie Wingate/Apa Publications

The nearby Ngadatgyi Pagoda features an enormous seated Buddha image, installed in 1657 by King Pindale, the ill-fated successor to King Thalun. Pindale was dethroned by his brother in 1661, and a few weeks later was drowned, together with his entire family (this was a common means of putting royalty to death as no blood was spilled on the soil).

Of rather more recent vintage is the Datpaungzu Pagoda, which was built only upon completion of the Myitkyina Railway. The monument provided a repository for relics from a number of other stupas which had to be demolished or relocated while clearing the way for the train line across the Ava Bridge.

Probably the most famous of all Sagaing’s temples, however, is the Kaunghmudaw Pagoda 5 [map], 10km (6 miles) northwest of the city on the far side of the Sagaing Hills. Built by King Thalun in 1636 to house relics formerly kept in the Mahazedi Pagoda in Bago (Pegu), it is said to contain the Buddha’s “Tooth of Kandy” and King Dhammapala’s miracle-working alms bowl. The Kaunghmudaw’s perfectly hemispherical shape is, according to legend, a copy of the breast of Thalun’s favourite wife. Its huge egg-shaped dome, 46 metres (151ft) high and 274 metres (900ft) in circumference, rises above three rounded terraces. The lowest is decorated with 120 nats and devas, each in its own niche. A ring of 812 moulded stone pillars, 1.5 metres (5ft) high, surrounds the dome; each one has a hollowed-out head in which an oil lamp is placed during the Thadingyut Light Festival on the occasion of the October full moon. Burmese Buddhists come to the Kaunghmudaw Pagoda from far and wide to celebrate the end of Buddhist Lent at this annual event.

Mingun

The trip up the Ayeyarwady to Mingun 6 [map], 10km (6miles) northwest of the city, deservedly ranks among the most popular half-day excursions from Mandalay, as much for the pleasure of the boat ride as the spectacle of King Bodawpaya’s immense, unfinished pagoda looming in surreal fashion above the river bank. In addition to the superb panoramic view from the top of the monument, the site also holds a couple of other photogenic buildings, as well as Myanmar’s largest bell, and is set amid some bucolic countryside.

A government-run boat service departs from Mandalay at 9am daily, returning at 1pm. The fact that most visitors use the service to get to Mingun means the site suffers from intense congestion from around 10am, and you may prefer to sidestep the crowds by travelling there by road earlier in the day (when the heat is less oppressive and the light more photogenic). Alternatively, wait until the afternoon, by which time all but a few stragglers will have headed homewards.

Mandalay “Combo” tickets cover admission to the site; otherwise, a small fee is levied at the foot of the steps leading to the pagoda. Refreshments and souvenirs are sold at the tea shops and stalls lining the road from the jetty.

The Mantara Gyi Pagoda

From a distance, the Mingun (Mantara Gyi) Pagoda’s appearance is just that of a large mound. Yet it has played an extremely important role in Burmese history during the last century. The pagoda was built between 1790 and 1797 by Bodawpaya, fourth son of Alaungpaya, the founder of the Konbaung dynasty. Bodawpaya’s forces had conquered Tanintharyi (Tenasserim), the Mon lands, Rakhine. He had underscored his invincibility by carrying off the Mahamuni Buddha statue from Mrauk-U to Amarapura and was at the peak of his power, wanting the world to see it.

In 1790, a Chinese delegation visited Bodawpaya’s court, carrying a tooth of the Buddha as a gift. Bodawpaya had the pagoda built to house the tooth – the same one that both Anawrahta and Alaungpaya coveted but had failed to obtain. He then moved his residence to an island in the Ayeyarwady for the next seven years while he supervised construction work on the pagoda. Bodawpaya intended to make his Mantara Gyi Pagoda ascend a full 152 metres (500ft) in height. In order to achieve this, he imported thousands of slaves from his newly conquered southern territories to work on the pagoda.

The lack of available labour in central Burma was irritating to Bodawpaya. Worrying rumours, which had circulated some 500 years earlier during the construction of the Minglazedi Pagoda, had resurfaced, and concerned voices were saying, “When the pagoda is finished, the great country will be ruined.” But Bodawpaya, convinced of his destiny as a future Buddha, was not to be dissuaded. He had the pagoda’s shrine rooms lined with lead and filled with 1,500 gold figurines, 2,434 silver images and nearly 37,000 other objects and materials, including a soda-water machine – just invented in England, according to the British envoy to Bodawpaya’s court, Hiram Cox. Only then were the shrine rooms sealed.

However, the economic ruin which raged at the turn of the 19th century persuaded Bodawpaya to halt construction work on the pagoda. The king died in 1819, aged 75, having ruled for 38 years. He left 122 children and 208 grandchildren – but none of them continued his work on the great pagoda.

Even though it was never completed, the ruins of the Mingun Pagoda are impressive. The upper sections of the pagoda collapsed into the hollow shrine rooms during the 1838 earthquake, but the base of the structure still towers nearly 50 metres (162ft) over the Ayeyarwady. An enormous pair of chinthe, also damaged in the quake, guard the riverfront view. The lowest terrace of the pagoda measures 137 sq metres (450 sq ft) in size and arches project from each of its four sides.

TMarket outside Shwebon Yadana (gilded thrown room), Shwebo.

Corrie Wingate/Apa Publications

The Mingun Bell

The famous Mingun Bell stands in an enclosure a short walk north of the main pagoda, just off the main street through the village. Weighing 87 tonnes and standing at 3.7 metres (12ft) high and 5 metres (16.5ft) wide, it was for many years the largest functioning bell in the world until being finally superseded by the the 116-ton Bell of Good Luck at the Foquan Temple, Henan, China, in 2000. King Bodawpaya had it cast in 1790 with the intention of dedicating it to his huge Mingun Pagoda, also intended to be the world’s largest. The difficulty of moulding and casting such an enormous clanger using 18th century techniques can hardly be underestimated – Bodawpaya himself recognised this fact and rewarded the creator of the bell by having him executed, so as to make sure the feat was never repeated elsewhere.

During the terrible earthquake of 1838, the Mingun Bell and its supports collapsed. Fortunately, there was no damage. Today, the bell is held up by heavy iron rods beneath a shelter. Small Burmese boys who frequent the site encourage visitors to crawl inside it while they strike the metal with a wooden mallet.

Shop

Mingun has some interesting shops where you can pick up inexpensive antique baskets and other handicrafts. There are also some artists’ studios that are worth browsing around.

Mingun’s other pagodas

Standing on the riverbank at the south side of the souvenir and tea stalls, the Pondaw Pagoda is a small replica of the original Mantara Gyi, yielding a clear idea of what the great stupa would have looked like had it been completed. A stone’s throw to the north, the whitewashed Settawya Pagoda was built by Bodawpaya in 1811 to hold a marble footprint of the Buddha.

Mingun’s prettiest stupa, however, stands at the far north of the village. The Hsinbyume or Myatheindan Pagoda was built by Bodawpaya’s grandson, Bagyidaw, in 1816, three years before he ascended the throne, as a memorial to his favourite wife, Princess Hsinbyume. Severely damaged in the 1838 earthquake, it was rebuilt by King Mindon in 1874. The building’s design is a rendition of the Sulamani Pagoda, believed to rest atop Mount Meru in the centre of the universe. The king of the gods, Indra (or Thagyamin as he is known to the Burmese), is depicted on the summit, surrounded by seven additional mountain chains, represented by seven wave-like railings leading to the central stupa. Five kinds of mythical monsters stand guard in niches around the terraces, though most have been defaced or beheaded by temple robbers. In the highest part of the stupa, reachable only by a steep stairway, is the cella, containing a single Buddha figure.

The nearby village of Taungbyon 7 [map], on the opposite side of the river some 20km (13 miles) north of Mandalay, is the focus of Myanmar’s largest and most intense nat festival (see box).

Mediums dance in one of the numerous shrines dedicated to the nats (spirits) during the Taungbyon Nat festival.

Getty Images

Festival of the Brother Lords

Each year for eight days before the full moon in August, the village of Taungbyon plays host to a major festival (there are smaller festivals in December and March). Tens of thousands attend the event, held since the 11th century in honour of a pair of nats (spirit heroes), known as the “Brother Lords”. Thought to have been the sons of a Muslim warrior who recovered the Mon’s Buddhist scriptures during Anawrahta’s conquest of Thaton, they became part of the labour force coerced by the king into building a pagoda in Taungbyon village, but collapsed from exhaustion and were executed for their frailty.

For reasons that have been lost in the mists of time, the Burmese mourned these two young men’s untimely demise with great passion. Their spirits soon became so powerful that a remorseful Anawrahta proclaimed them nat, ordering that a shrine be built in their honour in Taungbyon and a summer festival be held to venerate them annually.

The eight-day event, in which the brothers are represented by gilded wooden effigies that are ceremonially washed and paraded through crowds, now ranks among the most fervent displays of Burmese animism in the religious calendar. It features ritual floral offerings, wild hsaing waing music, spirit possession rituals and consultations with transvestite shamans, as well as an enormous bazaar, and lots of eating, gambling and carousing.

The Mingun Bell.

Corrie Wingate/Apa Publications

Further afield

The town of Monywa 8 [map], 136km (84 miles) west of Mandalay, sits on the banks of the Chindwin River, the largest tributary of the Ayeyarwady. A bustling, hot, flat market hub, it’s visited primarily as a base from which to take in the trio of monuments hidden in its rocky hinterland, as well as by a trickle of adventurous travellers ferry-hopping north or south along the Chindwin.

Tip

If you’re travelling by car between Mandalay and Monywa, Bodhi Tataung and the Thanboddhay Paya can easily be visited en route, as both lie close to the road between the two cities.

Monywa’s sights

Around 10km (6.2 miles) northeast of Monywa is the flamboyant Thanboddhay Pagoda 9 [map], built in 1939 by the much venerated Burmese abbot, Moehnyin Sayadaw. Guarded by a pair of huge white elephants, the complex consists of a central stupa surrounded by a forest of 845 smaller ones, all painted in a blaze of rainbow colours and encrusted with glass mosaic. The prayer hall inside (daily 6am–5pm; charge) is no less astonishing for its wealth of stucco figures. Among the myriad Buddha statues, look out for the finely dressed ladies with their parasols, the tigers and playful monks. The locals will tell you there are 582,357 images enshrined here altogether.

The Bodhi Tataung giant statues, near Monywa.

Corrie Wingate/Apa Publications

While Thanbodday may be famous for its host of tiny Buddhas, Bodhi Tataung ) [map], 8km (5 miles) further east, is renowned for its two extremely large ones. The first is a vast, 116-metre (424ft) standing Buddha – the Laykyun Setkyar – said to be the second biggest of its kind in the world (it’s just outstripped by China’s Spring Garden Buddha, though still nearly three times the height of New York’s Statue of Liberty). Stairways twist up through twenty-five storeys inside the colossus, climb through a series of galleries depicting hell at the bottom (with lurid scenes of demons torturing human souls, hammering stakes through hearts and cooking up stews of sinners in big pots) and then climbing up through the various Buddhist heavens on their way to nirvana at the top of the statue, although unfortunately at present visitors aren’t allowed beyond level 16, leaving you stranded slightly over halfway to paradise.

At the foot the standing giant sprawls an almost equally huge reclining Buddha, measuring 95 metres (312ft) from head to toe. This was the first statue to be completed on the site by its founding father, the Most Venerable Sayadaw Bhaddanta Narada, a local abbot who spent the last years of his life touring the world to raise funds for the project. Sadly, he died shortly before the mighty Laykyn Setkyar was finished.

Tens of thousands of smaller Buddha statues rest in neat rows under Bodhi trees radiating from the 131-metre (430ft) Aung Setykar Pagoda, on flat ground at the bottom of the complex, inaugurated in 2008.

The Naga Hills

Remote and unknown, the Naga Hills comprise a formidable geographical barrier along the Indian border in far northwestern Myanmar.

The Naga Hills of Myanmar, in the far north of Sagaing State a short distance west from the Kachin border, are as isolated as anywhere in Asia. Centred on the mountainous Angpawng Bum range, Burmese Nagaland comprises the eastern third of the Naga-inhabited hills straddling the Myanmar−India frontier

The term “Naga” is loosely applied to a group of more than 20 tribes inhabiting the border area. The many Naga languages belong to the Tibeto-Burman group of the Sino-Tibetan language family. Almost every village has its own dialect; different groups of Naga communicate in broken Burmese, Assamese, or sometimes in English and Hindi.

Most Naga live in villages strategically placed on hillsides near to water. Shifting cultivation (jhum) is commonly practised, although some tribes farm terraces where rice and millet are the staples. Weaving and woodcarving are also highly developed art forms, while Naga fishermen are noted for the use of intoxicants to kill or incapacitate fish.

Tribal organisation ranges from autocracy to democracy, and power may reside in a council of elders or tribal council. Descent is through the paternal line; clan and kindred are fundamental to social organisation. Due to missionary efforts in the 19th century, a sizeable majority of Indian Naga became Christians, although in Myanmar, animism remains predominant.

Political struggles

In the 1970s, Burmese Nagaland became a base for rebels fighting for independence in neighbouring Indian Nagaland. The National Socialist Council of Nagaland (NSCN), led by Indian Naga Isak Chishi Swu and Thuingaleng Muivah, together with the Burmese-born Naga S.S. Khaplang, who ruled the Burmese Naga Hills, preached a strange blend of nationalism and born-again Christianity under the slogan “Nagaland for Christ”.

In 1988, Khaplang rebelled against the Indian leadership of the NSCN and took over the rebel movement on the Burmese side of the border. He maintained a base in a remote area north of the town of Hkamti, on the Chindwin River, but in 2011, after securing autonomous status for the Nagas in Myanmar as well as top cabinet jobs for Naga leaders in the National Assembly, he signed a bilateral cease-fire.

One of the consequences of the truce is that foreigners can now undertake trips to the Naga homeland to experience the tribe’s flamboyant New Year celebrations, held in mid-January. Government-accredited tour operators can arrange the necessary permits for the trip, which take in the colourful, two-day Pole Erection ceremony, where Naga men don their finest traditional headdresses and jewellery, as well as soft treks to Naga villages.

Naga tribesmen.

Getty Images

Pho Win Taung caves

A considerably more ancient, neglected feel hangs over the Pho Win Taung cave complex, a cluster of 492 prayer chambers hewn from three sandstone outcrops 23km (14 miles) west of Monywa. Most were excavated between the 14th and 18th centuries, but with their peeling plaster murals and time-worn Buddha images they feel much older, like an apparition from the Central Asian silk route.

You’ll need a decent torch to admire the decoration of the caves’ interiors. Some were elaborately painted in geometric designs rendered in earthy reds, browns and blues. Others lead to colonnaded walkways lined with meditating or reclining Buddhas.

The fact that the site lies completely off the beaten track adds to its allure; come prepared for a total absence of facilities – as well as troupes of pilfering monkeys. Getting there under your own steam from Monywa can require some determination. You have to take an open-top ferry across the Chindwin and pick up a jeep from the far side for the remaining 22km (14 miles). Travelling by car, your driver will detour north to cross the Chindwin via the newly built river bridge, which takes you past the Shwetaung-U Pagoda (worth visiting for its panoramic views) and rather more unsightly Ivanhoe open-cast copper mine.

Shwebo

About 100km (60 miles) north of Mandalay, Shwebo ! [map] was the 18th-century capital of the warlike King Alaungpaya, founder of the Konbaung dynasty; it was from here that the reconquest of Burma began after the Mon had seized Inwa in 1752. Alaungpaya didn’t much care for its original name – “Moksovo”, meaning “the hunter chief” – and changed it instead to Shwebo, the “Golden Chief”, after which his home village of 300 houses grew to become a prosperous city. “Shwebo-tha!” (“Sons of Shwebo!”) was the battle cry of his marauding army, heard across the length and breadth of what is now modern Myanmar during the mid-18th century, in the course of which Alaungpaya’s Burmese forces first drove the Mon from Inwa and then rolled south, overrunning Mon territories, sacking their capital at Bago and taking control of what is now the whole of modern Myanmar (although with bits of India and Thailand).

Precious little remains from Alaungpaya’s illustrious era, his palace having long since burned to the ground, although the government recently erected replicas of the splendid throne halls, the Shwebon Yadana (daily 8am–5pm; charge), whose multi-tiered towers rise from lawned grounds in the centre of the city, overlooking remnants of the old moat. A memorial to the great king marks the spot where his body was cremated in 1760.

Also worth a visit, five minutes’ walk south of the old palace grounds, is the Shwe Daza Pagoda, which is thought to be five centuries old.

Halin

A millennium and a half before the rise of Alaungpaya and the Konbaung Dynasty, these same sun-scorched plains between the Ayeywarwady and Mu rivers gave rise to another important regional capital, the Pyu city of Halin (Halingyi). Hardly any visitors cover the 18km (11miles) of unsurfaced tracks and back roads separating Shwebo from the Halin Archaeological Zone @ [map] (Tues–Sun 9.30am–4.30pm; charge, admission with same ticket as Shwebon Yadana), but the site has a beguilingly forlorn atmosphere, while the adjacent village is dotted with dozens of ancient, crumbling monuments.

Reduced almost to dust and barely visible today, the Pyu settlement was surrounded by rectangular brick walls enclosing an area of roughly 500 hectares (1,250 acres). As at all Pyu cities the walls were pierced by 12 fortified gateways (equivalent to the signs of the zodiac), whose remains have been radiocarbon-dated to between the 2nd and 6th centuries AD. Excavations, conducted in three main waves during the 20th century and still ongoing, pockmark the site and its surrounding area, where numerous graves have been uncovered containing gold ornaments, bronze figures, seals and decorated weapons. Recently, local farmers also came across a skeleton with gold-inlaid teeth, which they were in the process of scraping clean when an archaeologist intervened and bought it off them.

The National Kandawgyi Gardens, Pyin U-Lwin.

Corrie Wingate/Apa Publications

Pyin U-Lwin

For anyone with a weak spot for the atmosphere of British colonial times, and others just seeking to escape the dusty misery of Mandalay’s hot season, a visit to Pyin U-Lwin (Maymyo) £ [map], in the foothills of the Shan Plateau, is a must. A two-and-a-half-hour drive by jeep takes the traveller to an elevation of 1,070 metres (3,510ft), from where there are breathtaking views of the Mandalay plain.

Pyin U-Lwin – originally “Maymyo”, or “May Town” – was named after one Colonel May, an officer in the Bengal Infantry who was posted to this hill station in 1887 in order to suppress a rebellion that flared up after the annexation of Upper Burma. At a strategically important point on the road from Mandalay to Hsipaw, the town, blessed with a temperate climate, served as the summer capital for the British administration until the end of the colonial era in 1948.

Tip

For a panoramic view of Pyin U-Lwin, climb to the hilltop Naung Kan Gyi Pagoda, north of the railway station.

Pleasant temperatures predominate in Pyin U-Lwin even during the hot season, and in the cold season there is no frost. It’s no wonder the British felt at home here. A number of Indian Sikhs and Nepalese gurkhas, whose forebears entered the country with the Indian army, have settled here, retaining many of the old colonial traditions in their work as hoteliers, carriage drivers and gardeners. They also run many of the tea shops in the hill resort.

Pyin U-Lwin also retains a bumper crop of former British country houses, many of which have been converted for use as small hotels. The best known is the former Candacraig (now called “Thiri Myaing”), to which servants of the Bombay Burma Trading Company used to repair for a spot of R&R. Built in 1905 in the style of an English country home, it still offers many of the traditional British comforts which once made the lives of the company’s clerks so pleasurable – freshly cooked English food, early-morning tea and a great big fireplace (although it’s currently closed for renovations).

Pyin U-Lwin also has a 175-hectare (430-acre) Botanical Garden (daily 7am–5.30pm; charge) where you can take a relaxing stroll or picnic by a lake. There is an 18-hole golf course and three waterfalls in the vicinity for swimming and picnics. Horse-drawn carriages resembling Wells-Fargo stage coaches are the chief mode of transport.

The resort’s cool weather has allowed many flowers and fruits commonly found in milder climes to thrive, including magnolias, chrysanthemums, cherry trees, peaches, strawberries and plums.

A horse-drawn carriage speeds through Pyin U-Lwin.

Corrie Wingate/Apa Publications

One of Naypyidaw’s extraordinarily spacious roads.

Getty Images

Twenty-seven km (15 miles) east of Pyin U-dwin are the Peik Chin Myaung caves (also known as Maha Nandamu; daily 6.30am–5pm; free), depicting scenes of Buddha’s life in fairy-tale surroundings. Most of the images have been donated by the leaders and family members of the present government to atone for sins previously committed.

Beyond Pyin U-Lwin, Myanmar’s northern and eastern frontiers are now accessible to foreigners. The rail line which passes through Pyin U-Lwin from Mandalay continues as far as the northern Shan administrative centre of Lashio. Further north, the road from Singu along the Ayeyarwady, opposite Kyaukmyaung, leads to the town of Mogok, famous for its ruby mines. Independent tourists are barred from visiting the area, although accompanied tours to the city are available through local travel agencies in Yangon and Mandalay.

Meiktila

Straddling a major crossroads at the head of the Sittaung Valley, the lakeside town of Meiktila $ [map] is infamous as the site of one of the fiercest Burmese battles in World War II. In late February 1944, Allied forces took the town from its poorly equipped Japanese defenders, only to find themselves under siege soon after. The ensuing fight dragged on for two months, until the fall of Rangoon sealed defeat for the Japanese – although not before virtually every Japanese soldier in Meiktila had been killed and the town itself reduced to rubble. A legacy of these events, and of Meiktila’s strategic position in the country’s heartland, is that today the town serves as the home of Myanmar’s largest air-force base.

More recently, in March 2013, the town hit the international headlines thanks to a series of anti-Muslim riots during which forty Muslims were killed and an estimated 12,000 others driven from their homes (while local police, it’s said, stood by and watched). The burnt-out and bulldozed remains of numerous houses, plus a pair of mosques, can still clearly be seen in the former Muslim district east along the road from the clocktower.

Despite recent troubles, Meiktila remains an enjoyable place to overnight at the crossroads on road and railway routes between Mandalay, Bagan and Inle Lake. There are few specific sights, but it’s a good place to soak up the atmosphere of life in small-town, provincial Myanmar, and the lively night market is one of the best in the region.

Centrepiece of the town is the beautiful Meiktila Lake, surrounded by assorted colourful temples and shrines including the eye-catching Phaung Daw U Pagoda, a floating temple built in the shape of a golden Karaweik bird. A scattering of stately old wooden mansions on the opposite, western shore, recalls the colonial era. Aung San Suu Kyi and her British husband, Michael Aris, spent their honeymoon in one of the largest of them.

Naypyidaw

There can be few capital cities in the world visited by virtually no tourists, but Naypyidaw % [map] – also spelt “Nay Pyi Daw”, “Nay Pyi Taw” or “Naypyitaw” (literally “Abode of Kings”) is one of them. Built from scratch, at vast expense and with considerable haste, the project was the brainchild of Senior General Than Shwe. No one is quite sure why, in 2002, the former Commander-in-Chief of the Myanmar armed forces decided to move the Burmese seat of government 320km (200 miles) north up the Sittaung Valley from Yangon: the official reason was “lack of space”. It was, however, widely rumoured at the time that Than Shwe’s personal astrologer had foreseen some kind of foreign invasion by sea, and that the general preferred this much more easily defensible site in the centre of the country.

White elephant at the Hsin Hpyu Daw park.

Corrie Wingate/Apa Publications

White elephants

A party was thrown in the Burmese capital, Naypyidaw, in November 2011 to welcome a pair of white elephants into captivity after they’d been captured in the jungles of Rakhine State. Symbols of power and good fortune, white (or albino) elephants are regarded as auspicious in Myanmar. So seriously do Myanmar’s generals take the old dictum that these rare animals confer blessings on heads of state that they even name their personal aircrafts “White Elephant 1” and “White Elephant 2”. Myanmar today boasts a total of eight such animals, with three of them housed on the northern outskirts of Yangon, in a park close to the airport, and the other five in Naypyidaw.

Whatever its inspiration, Naypyidaw, 252km (157 miles) south of Mandalay, is here to stay. A sprawling, soulless, white-elephant city of empty 8-lane highways and giant concrete buildings, it cost an estimated $4-billion to create and required the relocation of hundreds of thousands of government employees (many of whose families still reside in Yangon).

Much of the new construction consists of sprawling, Lego-like suburbs whose roofs are colour-coded to denote the rank or job of their inhabitants. Widely spaced so as to minimise the potential impact of air raids, these are already showing signs of age, with peeling plaster and mildew-streaks staining their walls. The top brass, meanwhile, live in swanky mansions and Orange-County-style villas in the suburbs and surrounding hills, complete with secret bunkers and tunnels.

Naypyidaw is decidedly not somewhere you come for sightseeing, so much as for its strange, slightly sinister, atmosphere. But the city does boast one stand-out monument: the huge, gold-covered Uppatasanti Pagoda. An almost exact replica of Yangon’s Shwedagon Pagoda, the giant stupa was donated by General Than Shwe and his wife and is hollow, containing dioramas illustrating scenes from the life of the Buddha. On the east side of the stupa, look out for the shelter where the general’s much-prized quintet of white elephants are housed.

Tip

Be careful where you point your camera in Naypyidaw. Photographing military or government buildings, soldiers, police and officials is strictly forbidden.

Visits to the government enclave, with its 31-building Parliament complex, are not allowed. Also off limits is the military zone in Pyinmana to the east, which is a pity as the latter holds the most outlandish of all the follies erected in the new capital by the regime – a vast square overlooked by three colossal statues of Burma’s great kings: Anawrahta, Bayinnaung and Alaungpaya. The space serves mainly as a venue for displays of military might.

The only other major sight of note in Naypyidaw is the city’s showpiece Zoological Gardens and Safari Park (Tue–Sun 8.30am–8pm; charge), a forty-minute taxi ride northeast of the centre, where you can see everything from alpacas to zebras.

The mighty steel girders of the Gokteik Viaduct.

iStock

From Pyin U-Lwin to Lashio by Train

The train journey from Pyin U-Lwin to Lashio is Myanmar’s most picturesque rail route, taking in the magnificent Gokteik Viaduct.

Although the train from Pyin U-Lwin originates in Mandalay, many travellers prefer to board it at the hill station, something which saves time as the 45-minute road journey is more than three hours shorter. Departures are also later in Pyin U-Lwin (in Mandalay, it starts at an uncomfortable 4.45am); and besides, the most interesting part of the journey is from Pyin U-Lwin to Lashio.

Pyin U-Lwin to the viaduct

The rail journey starts in Mandalay Division, but most of the towns it passes through are in northern Shan State.

Until 1995, these towns were unexplored, as the route from Mandalay to Lashio was considered a haven for bandits. When this problem was eliminated, restrictions on train travel by foreigners were also lifted. Although it is possible to go by road, the train provides a more comfortable ride, albeit in carriages that have seen better days. The journey covering the 220km (146 miles) between Pyin U-Lwin and Lashio takes about 15 hours and is a great way to glimpse northern Shan State.

After Pyin U-Lwin, the train passes gardens full of cabbages and strawberries which soon open out into broad valleys dotted with hamlets. Mist-covered mountains loom in the distance as Wetwun, the first stop 90 minutes later, approaches. As soon as the train stops, vendors hop on board to sell snacks.

The highlight of the journey is the Gokteik Viaduct, which is a magnificent steel bridge spanning a 300-metre (990ft) -deep river gorge, which the train passes after Wetwun. The approach is stunning – the giant steel girders stand out from the dense jungle like silver latticework, set against a craggy, ochre mountain face. The steel viaduct was something of an engineering marvel when it was completed in 1903. In his book, The Great Railway Bazaar, Paul Theroux, who travelled this way in 1973, described it as “a monster of silver geometry in all the ragged rock and jungle… Its presence there was bizarre, this man-made thing in so remote a place, competing with the grandeur of the enormous gorge and yet seemingly more grand than its surroundings, which were hardly negligible – the water rushing through the girder legs and falling on the tops of trees, the flight of birds through the swirling clouds and the blackness of the tunnels beyond the viaduct.”

Beyond the viaduct

After crossing the viaduct, the train passes through lush valleys surrounded by green mountains. The following stop, Kyaukme, is deep in Shan territory and dotted with Shan hill-tribe villages. Green valleys soon give way to rice fields, banana plantations, bamboo groves and orange orchards on the approach to the next station, Hsipaw. The train then snakes through jungle-clad valleys cut through by the rapid-strewn, emerald-coloured Namby River, which flows all the way to Lashio. By twilight, the panorama fades and darkness envelopes the rest of the ride until Lashio is reached at about 9pm.