The arid plains around Bagan hold several options for day trips should you feel like a break from the ruins. An hour-and-a-half’s drive southeast, Mount Popa is an extinct volcano whose dramatic profile can be seen on the horizon in clear weather, and where a geological curiosity – a craggy basalt plug – has become the country’s principal centre for nat worship. It’s worth making the trip just for the views to be had from the top of the hill, which surveys an awesome sweep of mountainous landscape. The village, visited in huge numbers during two annual temple festivals, even boasts a decent hotel should you be tempted to stay the night for the trek up to the nearby volcano early the following morning.

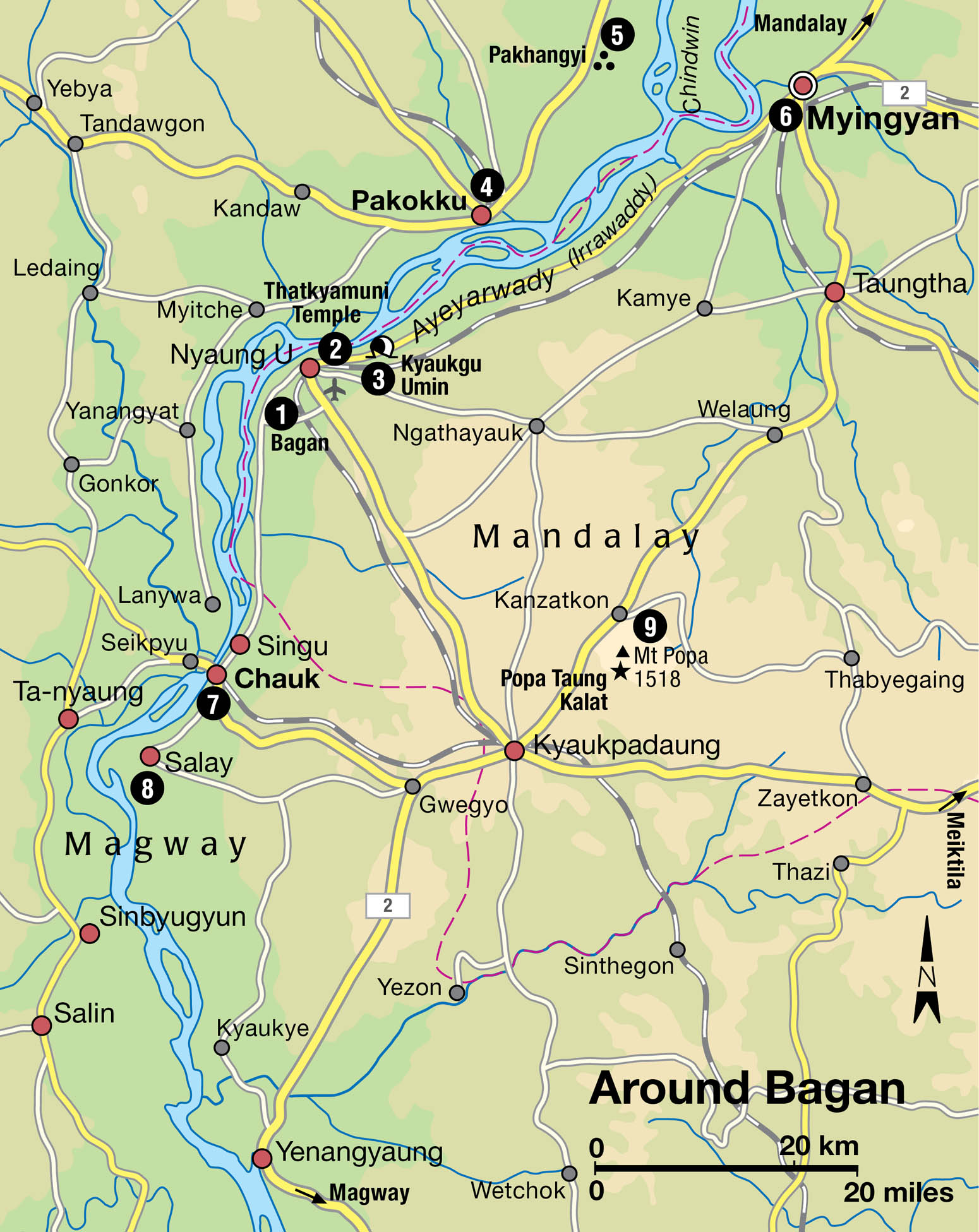

Closer to Bagan 1 [map], a cluster of off-track ancient temples lies upriver, reachable by boat from the jetty at Nyaung U, while the region’s market towns provide a splash of local atmosphere.

Shin Upagot statue shrine, Mount Popa.

Corrie Wingate/Apa Publications

Temples upriver from Nyaung U

Boats can be chartered throughout the day from Nyaung U’s little jetty for trips to a trio of small temples upstream – an excursion of around three or four hours including stops at the monuments.

The first site you come to, 1km (0.6 mile) north, is the 13th-century Thatkyamuni Temple 2 [map], in which panels of murals depicting Ashoka, the great Mauryan Emperor who ruled in India during the 3rd century BC, adorn the walls. Other scenes record the introduction of the Buddhist faith to Sri Lanka. On a low hill close by, the Kondawgyi Temple was a contemporary of the Thatkyamuni, and also holds some paintings, this time of Jataka scenes and floral patterns.

The Pandaw III takes to the water.

Pandaw Cruises Pte Ltd

The boats continue for 3km (2 miles) until they reach a clay escarpment overlooking the Ayeyarwady, from which the Kyaukgu Umin cave temple 3 [map] surveys the river. A maze of passages leads into the caves behind: the stone-and-brick-built chamber is in fact an enlargement of the natural hollow. A large Buddha sits opposite the entrance, and the walls are embellished with stone reliefs. The Kyaukgu Umin’s ground storey dates from the 11th century; the upper two storeys have been ascribed to the reign of Narapatisithu (1174–1211).

This wood will be used as fuel to heat palm sugar and turn it into jaggery.

Corrie Wingate/Apa Publications

Pakokku

Further afield, the town of Pakokku 4 [map], on the right bank of the Ayeyarwady, made international headlines during the so-called “Saffron Revolution” of 2007, when local monks spearheaded a protest against a sudden rise in petrol prices. The protest subsequently went national and led to a massive military clampdown on pro-democracy campaigners.

A local scoops her kid goat into her arms.

Corrie Wingate/Apa Publications

There’s little to see in the town beyond the local market, which specialises in tobacco and thanaka wood. But with a little time on your hands a commendable side trip would be the 20km (12-mile) foray northeast to visit the 19th-century ruins of Pakhangyi 5 [map], comprising old city walls, an archaeological museum and a great wooden temple – one of the oldest in Myanmar – supported by a forest of more than 250 teak pillars.

Myingyan and the Chindwin River

About equidistant between Mandalay and Bagan, on the left bank of the Ayeyarwady, the Bamar market town of Myingyan 6 [map] is both an important river port and cotton-trading centre, forming a junction between a branch railway to Thazi and the main line between Yangon and Mandalay. There isn’t much of historical interest on offer, the central market is thriving, and the almost complete lack of western visitors offers a real taste of life well off the tourist trail.

Myingyan is located just downstream from the mighty Chindwin River, the main tributary of the Ayeyarwady.The Chindwin is formed in the Patkai and Kumon ranges of the Indo-Myanmar border by a network of headstreams including the Tanai, Tawan and Taron. It drains northwest through the Hukawng valley and then begins its 840km (520-mile) main course. The Chindwin flows south through the Naga Hills and past the towns of Singkaling Hkamti, Homalin, Thaungdut, Mawlaik, Kalewa and Monywa. Below the jade-rich Hukawng valley, falls and reefs interrupt it at several places. At Haka, goods must be transferred from large boats to canoes.

The Uyu and the Myittha are the main tributaries of the system, which drains around 114,000 sq km (44,000 sq miles) of northwestern Myanmar. During part of the rainy season (June–November), the Chindwin is navigable by river steamer for more than 640km (400 miles) upstream to Singkaling Hkamti. The Chindwin’s outlets into the Ayeyarwady are interrupted by a succession of long, low, partially populated islands. According to tradition, the most southerly of these outlets is an artificial channel cut by one of the kings of Bagan. Choked up for many centuries, it was reopened by an exceptional flood in 1824.

The process of pressing peanuts to extract the oil.

Corrie Wingate/Apa Publications

Chauk, Sale and Kyaukpadaung

About 30km (19 miles) south of Bagan, Chauk 7 [map] is a small town and petroleum port for the Singu-Chauk oil fields.

Just 8km (5 miles) south of Chauk, the small riverside settlement of Salay 8 [map] (also spelt Sale) developed as an adjunct of Bagan during the 12th and 13th centuries. It’s now an increasingly popular half-day trip from Bagan (or full day in combination with Mount Popa), with a cluster of still active Buddhist temples and monasteries, some fascinating colonial architecture, and a number of little-visited ruins. Particularly interesting is the magnificent Yoke Sone Kyaung (daily 9am–4pm; charge). Built in 1882, this is one of Myanmar’s most impressive surviving 19th-century wooden buildings, decorated with flamboyant Jataka carvings outside and full of intricately carved shrines within.

Popa

The most popular excursion from Bagan is to the nat temple at Popa Taung Kalat, 50km (30 miles) southeast. Confusingly, this spectacular pilgrimage place, which centres on an eerie outcrop of rock rising sheer from the plains, is often referred to as “Mount Popa”, although strictly speaking this is the name of the much larger mountain rising immediately to the east. While the former can be reached in an easy day trip from Bagan, the latter massif requires a dawn start and a full day of leg work to ascend, for which you’ll need to stay in the area.

The name “popa”, Sanskrit for “flower”, is believed to derive from the profusion of blooms nourished by the famously fertile soil of the mountain. Local legend asserts that the volcano first appeared in 442 BC after a great earthquake forced out of the Myingyan plains. Volcanic ash gradually coalesced into rich soil, and the great peak was soon festooned with flowers. For the inhabitants of the surrounding regions this seemed a true miracle and Popa soon became legendary as a home of the gods – the “Mount Olympus” of Burma. Alchemists and occultists settled on its slopes, and people generally became convinced that mythical beings, the nat, inhabited its woods.

Popa Taung Kalat

The plug of an extinct volcano, the weirdly shaped hill of Popa Taung Kalat is with the major centre of nat worship in Myanmar, particularly associated with the four “Mahagiri” (“Great Mountain”) nats who are believed to reside on nearby Mount Popa, as well as the many other nat spirits of the Burmese supernatural pantheon. Worshippers from all over Burma come here to propitiate the assorted spirit deities installed both in the nat temple at the base of the hill (with its impressive, slightly spooky gallery of nat mannequins) and in the various shrines which dot the steps up the hill.

Tip

Come prepared if you plan to climb Popa Taung Kalat. The ascent takes less than half an hour but is a fairly stiff climb. Bring a hat or parasol, and ensure that you have plenty of water with you.

From the nat temple, a covered walkway lined with stalls selling religious souvenirs winds steeply up the hill itself, culminating in a small, 737-metre (2,417ft) plateau. The walk up takes around 20 minutes and ends at a gleaming complex of Buddhist and nat shrines from whose terrace a magnificent panorama extends across the plains to the Rakhine hills, rising from the dust haze on the horizon. Look out for the voracious macaques that patrol the steps and are not averse to snatching titbits from pilgrims’ hands.

Mount Popa

Technically a spur of the Bago Yoma range, Mount Popa 9 [map] is an extinct volcano rising due east of Taung Kalat to a height of 1,518m (4,981ft). Numerous trails lead through the lush forests wrapped around the mountain’s flanks to the spectacular, 610-metre (2000ft) caldera marking its summit. Far-reaching views are guaranteed from the very start of the strenuous four-hour trek, for which guides can be arranged through the Popa Mountain Resort (For more information, click here). Bird-spotters will find plenty to get excited about flitting through Popa’s pristine jungle, home to 176 species, including two endemics (the Burmese bushlark and hooded treepie), as well as 65 different kinds of orchid.

Nat deities inside the nat temple at the base of Mount Popa.

Corrie Wingate/Apa Publications

Nat worship

The veneration of spirit heroes known as nat is peculiar to Myanmar, where it runs in parallel and seeming harmony with the rituals of Theravada Buddhism. Nat shrines often appear next to, and frequently inside, Buddhist temples, and Burmese worshippers tend to see no contradiction in this, even though numerous kings tried to stamp out the tradition. After failing spectacularly in the 11th century, King Anawrahta chose to incorporate nat into local Buddhist mythology – albeit in an inferior position to the Buddha himself.

It was Anawrahta who first fixed the nat pantheon, incorporating 37 of the most popular nat spirits and naming them the “Great Nats” – although many other nats not included in Anawrahta’s selection continue to be venerated, including the four Mahagiri (“Great Mountain”) nats of Mount Popa and many other local deities around the country. Numerous temples are dedicated to the flamboyant 37 Great Nats, all of whom have their own peculiar origin myths and proclivities. All died violent deaths – all, that is, except Thagyamin (a Burmese version of the Hindu god Indra), the King of the Nats, usually portrayed riding a three-headed white elephant and carrying a conch shell.

Believers propitiate different nat depending on what they need; an offering will be made at a local shrine or, perhaps, a visit will be made to a temple of national importance, such as the great Popa Taung Kalat temple. However, nat worship is practised in its most fervent form at nat pwes, annual festivals where special oracles called natkadaws dominate proceedings. After a serious drinking session, the natkadaws enter trances during which they’re possessed by the presiding nat and appeased with offerings by worshippers.

The legend of the Mahagiri Nat

A trip to the shrine of the Mahagiri Nat, situated about halfway up the mountain, is an essential part of a visit to Mount Popa. For seven centuries preceding the reign of Anawrahta, all kings of central Burma were required to make a pilgrimage here to consult with the two powerful nat about their reign.

The legend begins with a young blacksmith, Nga Tin De, and his beautiful sister who lived outside the northern city of Tagaung in the mid-4th century, when King Thinlikyaung ruled in the Bagan area. Perceived by the king as a threat, he was forced to flee into the woods. The king then became enchanted with the blacksmith’s sister, and married her. He then convinced his wife that Nga Tin De was no longer his rival and he asked her to call her brother back from the forest. But when Nga Tin De emerged, he was seized by the king’s guards, tied to a tree and set alight.

As the fire lapped at her brother’s body, Shwemyethna broke free from her escorts and threw herself into the blaze. Their physical bodies gone, the siblings became mischievous nat living in the saga tree. To stop them from causing him harm, the king had the tree chopped down and thrown into the Ayeyarwady. The story of their deaths spread rapidly throughout Burma. Thinlikyaung, who had wanted to unite the country in nat worship, learned that the tree was floating downstream through his kingdom. He ordered the tree fished out of the river and had two figures carved from it. The nat images were then carried to the top of Mount Popa and given a shrine where they reside to this day. Every king crowned in Bagan between the 4th and 11th centuries would make a pilgrimage to the brother and sister nat, who would supposedly appear before the ruler to counsel him.

Two other nats also subsequently became closely associated with Mount Popa. The story begins with Mai Wunna (“Miss Gold” – aka Popa Mai Daw, or the “Queen Mother of Popa”), a flower-eating ogress who is said to rule over the mountain. Mai Wunna, according to legend, fell in love with a certain Byatta, an Indian Muslim in the service of King Anawrahta. Byatta was subsequently executed for neglecting his duties, after which Mai Wunna died of a broken heart. Their two sons, Min Gyi and Min Lay were also later executed by Anawrahta, becoming nats in their turn. The nat pwe festival celebrated in their honour at Taungbyone, near Mandalay, remains to this day one of the country’s most popular and riotous religious events.