CHAPTER 2

Fiasco

On January 13, 1842, a British sentry at Jalalabad, in Afghanistan, looked out into the distant hills. Where was the British army of fifteen thousand men, women, and children that set out from Kabul a week before?

The sentry saw only a dark speck. Through field glasses, it turned out to be a man clinging to a stumbling pony. The gate was thrown open and soldiers rushed out to meet the rider. He was William Brydon, a thirty-year-old Scottish doctor from Kabul. Brydon’s body was cut and bruised. His feet were swollen by frostbite. His pony was on the brink of death. The soldiers asked: What happened to the army? Brydon answered, “I am the army.”1

The First Anglo-Afghan War began three years earlier, in 1839, when Britain invaded Afghanistan. It was the height of Pax Britannica, or the era of British global power. In Central Asia, Britain and Russia competed for supremacy in a high-stakes contest known as the Great Game. London was gripped by paranoia that Afghanistan would fall into the Russian orbit, threatening India, and decided to preempt the danger by forcible regime change.

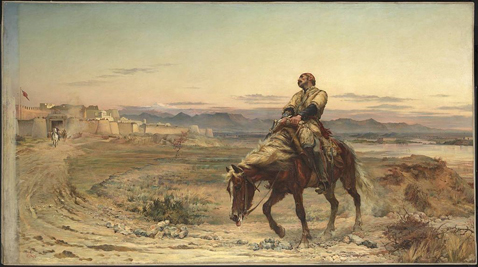

Elizabeth Butler’s 1879 painting The Remnants of an Army depicts William Brydon’s arrival at Jalalabad.

British troops quickly captured Kabul, toppled Dost Mohammad Khan, the Afghan king, and installed the former ruler, Shah Shuja, in his place. The war was over, it seemed, and British officers took to hunting and playing cricket. The new arrivals imported the necessities of imperial rule, including a grand piano, ceremonial kilts, a parakeet, numerous maidservants, and a wine cellar carried by three hundred camels.

For the British, Shah Shuja was a pliable fellow. For the Afghans, he was an illegitimate puppet. In 1840, an armed rebellion began in Pashtun areas of Afghanistan and quickly swept toward Kabul. Mountstuart Elphinstone, who served in the British East India Company, said it was a hopeless task to maintain Shuja “in a poor, cold, strong and remote country, among a turbulent people like the Afghans.”2 As the mission degenerated into a military fiasco, the only question was: How costly would the British loss be?

Everything hinged on the exit strategy. “You have brought an army into the country,” said one Afghan chieftain. “But how do you propose to take it out again?”3 The British decided to retreat from Kabul to the closest garrison, Jalalabad, ninety miles away. And so, at first light on January 6, 1842, in the midst of the Afghan winter, 4,500 soldiers and over 10,000 camp followers set out for the mountain passes. “Dreary indeed,” recalled Lieutenant Vincent Eyre, “was the scene over which, with drooping spirits and dismal forebodings, we had to bend our unwilling steps.”4

The shambling mass waded through feet of snow with little food or shelter. The soldiers’ mustaches and beards were coated in icicles. Their eyes were afflicted by snow blindness. Their frostbitten feet looked like charred logs of wood. Some were captured or hacked to pieces by Afghan tribesmen. Many died of starvation or exposure. Others gibbered in madness or took their own lives. “The snow was absolutely dyed with streaks and patches of blood for whole miles,” wrote Eyre, “and at every step we encountered the mangled bodies of British and Hindustani soldiers and helpless camp-followers, lying side by side… the red stream of life still trickling from many a gaping wound inflicted by the merciless Afghan knife.”5

For the rest of his life, Captain Colin Mackenzie remembered the image of a naked Indian child sitting alone and abandoned on the snow plain. “It was a beautiful little girl about two years old, just strong enough to sit upright with its little legs doubled under it, its great black eyes dilated to twice their usual size, fixed on the armed men, the passing cavalry and all the strange sights that met its gaze.”6 Mackenzie wanted to save the child, but there were too many others alone on the path. He had no choice but to leave her there to die.

The black column of soldiers and refugees thinned like a starving snake. By January 12, a rump force of barely two thousand found their way blocked by swarming tribesmen. A few dozen broke through the enemy lines on horseback. All of them were cut down—except one. Chewing on licorice roots to stave off thirst, Brydon reached Jalalabad to tell the tale.

Soldiers in the fort played bugles to guide any last stragglers to safety. “The terrible wailing sound of those bugles I will never forget,” wrote Captain Thomas Seaton. “It was a dirge for our slaughtered soldiers and, heard all through the night, it had an inexpressibly mournful and depressing effect.”7

After the British withdrew, Dost Mohammad Khan regained his throne. “Not one benefit, political or military, has been acquired with this war,” wrote Reverend G. R. Gleig, the British army chaplain in Jalalabad. “Our eventual evacuation of the country resembled the retreat of an army defeated.”8

The British intervention in Afghanistan is an example of a fiasco, or an unwinnable war. This book is a guide to handling fiascos; so let’s take a closer look at the concept.

Fiascos happen in wars of limited interests, or military campaigns that don’t directly imperil a country’s physical security. Wars of national survival, like the world wars, are life-and-death struggles where leaders may need to do whatever it takes to achieve a decisive result. “You ask, what is our aim?” said Winston Churchill in World War II. “I can answer in one word. It is victory, victory at all costs, victory in spite of all terror, victory, however long and hard the road may be; for without victory, there is no survival.”9

By contrast, wars of limited interests involve lower stakes. The fighting is in a more distant location. The military deployment is smaller. The homeland is not at risk. Therefore, countries can’t justify an endless commitment. In the 1840s, for example, Britain had only limited interests in Afghanistan and couldn’t keep fighting indefinitely.

Fiascos are triggered by a major military failure. The battlefield situation has deteriorated alarmingly. The wheels are coming off. By the start of 1842, the British faced a dramatically worsening situation as the insurgency reached Kabul.

If a country’s interests in the conflict are sufficiently restricted, and the battlefield failure is sufficiently extreme, the result may be an unwinnable war. A decisive victory can no longer be achieved at a reasonable cost. Overthrowing the adversary will forfeit too much blood and treasure, reap too small a dividend, take too long, erode public support, or damage wider objectives. In 1842, the British had no plausible path to a meaningful victory in Afghanistan.

It’s sometimes tough to identify exactly when a war turns into a fiasco. In other words, there’s no simple metric for determining if a conflict is unwinnable. In the end, claiming that decisive victory is off the table is a judgment call. We must identify what victory represents and estimate the costs, benefits, and risks of seeking this outcome—all based on the unique nature of the campaign.

This assessment may be subjective but it’s not arbitrary. As the military situation steadily worsens, the reality of a fiasco becomes increasingly clear. In other words, when the war effort first starts to deteriorate, the situation is often ambiguous and debatable. Then, if the decline continues further, the implausibility of achieving victory comes into sharp focus. At the extreme, following a severe battlefield reversal, the grim truth of an unwinnable war is self-evident. Later, we’ll look in more detail at the challenges of assessing progress in wartime—especially in counterinsurgency campaigns—as well as some solutions.

In the wake of a fiasco, leaders must find an exit strategy to cut the nation’s losses and protect its interests and values. They need a substitute for victory, such as a tough draw or a tolerable failure.

The idea of cutting losses, or fighting for less than victory, isn’t easy for Americans to accept. We like decisive results. American sports matches, for example, almost always end in a clear win or a loss, whereas European sports like soccer and cricket often result in a tie. “If you tried to end a game in a tie in the United States,” said NBC’s fictional coach Ted Lasso, “heck, that might be listed in Revelations as the cause for the apocalypse.”

During the 2014 soccer World Cup, the United States played Germany in the final group game. Because of other results, the United States could progress if it won, drew, or even if it lost—as long as it was by a narrow margin. The idea of losing in the right way seemed risible to many Americans, and reinforced the idea that soccer is an alien sport. “This is the United States of America,” said one commentator. “We do not play for ties, or celebrate advancing solely because another team lost.”10

In a similar vein, we tend to see the outcome of war in binary terms as a victory or a defeat. Any negative U.S. military result is placed in the defeat bracket and feels almost equally intolerable. Who wants to scrape a draw or lose by less? This is the United States of America.

The outcome of war, however, is not binary. Instead, there are many gradations of success and failure. An unwinnable war means that decisive victory has been removed from the list of possible outcomes. But this still leaves a wide range of potential results, including a marginal success, a tough draw, a partial failure, or an outright catastrophe. The difference between a draw and a disaster may equal thousands of lives. Therefore, in an unwinnable war, there’s still a great deal to play for.

In January 1842, for example, there were many possible resolutions to the First Anglo-Afghan War. None of them involved a British victory. Some roads led to a modest failure. Other paths ended in military catastrophe. Britain chose poorly and lost an entire army.

The British retreat from Kabul is the wrong way to lose a war. But is there a right way to lose a war? Is it possible to end a deteriorating conflict without leaving a sole survivor clinging to an injured pony and a dying child along the path?

The success of an exit strategy is about much more than just returning the troops. Otherwise the mission can turn into what foreign affairs analyst Gideon Rose called a “moon landing,” designed to transport soldiers far away and bring them home safely with little regard for what’s left behind.11

Ultimately, an exit strategy should be assessed based on a cost-benefit analysis. Did officials use the available resources efficiently to achieve political goals, limit the loss to national interests and values, and maximize potential gains? Did they carefully compare different courses of action—escalation, de-escalation, or negotiation—and choose the best option? Or were other, and likely more effective, paths out of the conflict available but ignored?

Today, the problem of resolving a fiasco has become all too familiar. Since 1945, four out of five major American wars became unwinnable: Korea, Vietnam, Afghanistan, and Iraq. The only exception—where victory remained on the table—was the Gulf War. How well did the United States handle these military crises?

America’s record of dealing with fiascos is largely one of failure. In other words, Washington responded to battlefield reversals in ways that made a poor situation even worse. We stumbled over the finish line, not just losing but losing badly. Let’s take a closer look at U.S. exit strategies in Korea, Vietnam, Afghanistan, and Iraq—as an important step in discovering the right way to end a difficult war.

Old Baldy

On November 24, 1950, Douglas MacArthur, the commander of U.S. forces in Korea, launched “the end of the war offensive.” American and allied troops had pushed North Korea out of the South, crossed the 38th parallel into the North, captured Pyongyang, and were advancing toward the Chinese border. North Korea was about to be liberated. The iron curtain in East Asia was about to be rolled back. MacArthur said he would bring the boys home by Christmas.

But American soldiers were walking into a trap. Beijing had repeatedly signaled it would intervene rather than accept the fall of North Korea. Washington dismissed the threat as a bluff. Reports emerged of thousands of Chinese troops in North Korea. The danger was brushed aside. Chinese forces mauled several South Korean divisions and then vanished like ghosts. The peril was again ignored. American troops rushed north with confidence born from a century of golden victories and a seemingly invincible commander in MacArthur.

On November 27, Sergeant Gene Dixon was serving with the U.S. Marines near the Chosin Reservoir in North Korea when “all hell broke loose.”12 In a coordinated assault, three hundred thousand Chinese troops struck U.S. and allied forces. “It seemed as if the Chinese were coming at us from all directions,” said Dixon, “blowing bugles and yelling throughout the night.” Wearing only quilted cotton jackets in a Siberian winter, the Chinese soldiers attacked at close range with machine guns and hand grenades. One Communist general told his men: “Kill these Marines as you would kill snakes in your homes.”13

“I couldn’t believe my eyes when I saw them in the moonlight,” recalled Marine Corporal Arthur Koch. “It was like the snow come to life, and they were shouting and shaking their fists—just raising hell.… The Chinese didn’t come at us by fire-and-maneuver, the way Marines do; they came in a rush like a pack of mad dogs.”14