CHAPTER 9

Aftermath

In December 1979, a force of seven hundred elite Soviet soldiers seized control of Kabul. Moscow’s target sights were locked on the Afghan president, Hafizullah Amin. He was a Communist—but also an incompetent Communist. Amin couldn’t rule effectively. Leftist factions in Afghanistan were at each other’s throats. There was a full-blown jihadist insurgency. The USSR decided enough was enough and launched Operation Storm-333.

Amin heard that his palace was under assault but remained confident of survival. The Soviets, he said, would dispatch a rescue mission. Then Amin was told the Soviets were the ones attacking. Moscow’s forces overcame stiff resistance and killed the Afghan president. The tempest in Kabul was just the beginning, as one hundred thousand Soviet troops rumbled into Afghanistan from the north.

The United States saw the invasion of Afghanistan as a carefully orchestrated act of Soviet expansion. But there was no master plan. The sclerotic Politburo improvised the whole adventure. Moscow hoped that a quick and decisive show of force would create a stable and friendly regime on the border. Hungary in 1956, Czechoslovakia in 1968, and Afghanistan in 1979: three-for-three.

Washington, however, had a different historical parallel in mind. On the day of the invasion, Zbigniew Brzezinski, Jimmy Carter’s national security advisor, told the president, “We now have the opportunity of giving to the USSR its Vietnam War.”1

Like many countries that invade Afghanistan, the Soviet Union didn’t get the war it expected. The alien Soviet presence provoked an antibody response in the form of the mujahideen insurgency. Moscow responded with a brutal campaign of repression. At the first sign of resistance, entire villages were destroyed. Afghanistan became an empire of graveyards.

The mujahideen received aid from a diverse coalition, including China, Pakistan, Saudi Arabia, Osama bin Laden and his legion of Arab fighters, and the United States. Charismatic Texas congressman Charlie Wilson pressed Washington to step up arms supplies to the Afghan rebels, including, most famously, the Stinger ground-to-air missile.

The Soviets were adrift in a war they didn’t understand. But one man saw things clearly: Mikhail Gorbachev. In 1985, Gorbachev rose to power in Moscow intent on revitalizing the USSR through economic and political reform. Change at home required suturing what Gorbachev called the “bleeding wound” in Afghanistan.2 “We have been fighting already for six years,” declared Gorbachev at a Politburo meeting in 1986. “If we don’t change our approach we will fight for another twenty to thirty years. Are we going to fight forever, knowing that our military can’t handle the situation?”3

Gorbachev broadly followed a surge, talk, and leave exit strategy. He initially sent reinforcements to buttress the Soviet position. Then he “Afghanized” the war effort by stepping up the training of local forces. And he also pursued peace negotiations with the United States. In 1988, Afghanistan and Pakistan signed the Geneva Accords, with Washington and Moscow as guarantors. The accords laid out a road map for the Red Army’s exit by 1989. The withdrawal took only nine months and Moscow’s troops left in good order.

Gorbachev tried to tell a positive story about the campaign. Soviet soldiers had achieved their goal of Afghan reconciliation and could leave with their heads held high (the rhetorical tactic of keeping control). Gorbachev also deliberately emphasized the role of the United Nations in the withdrawal and portrayed the departure as an effort to revitalize the international organization (a classic example of leaving from behind).4

Moscow attempted to end the mission on a high note. On February 15, 1989, General Boris Gromov was officially the last Soviet soldier to leave Afghanistan. Under a media glare, Gromov walked across the Friendship Bridge between Afghanistan and the USSR, embraced his young son, and received a bouquet of red carnations. It was all a charade. Gromov had been living on the Soviet side of the border and only traveled to Afghanistan for this moment of theater.

The last Soviet troops leave Afghanistan in a stage-managed exit. (RIA Novosti archive, A. Solomonov, CC-BY-SA 3.0, Wikimedia Commons)

Another Soviet soldier left Afghanistan on February 15. It was the dead body of a paratrooper, carried across the Friendship Bridge in a blanket with little fanfare. He was the last of fourteen thousand official Soviet fatalities in the Afghanistan War (the real figure may be several times as high). The harvest of war also included tens of thousands of wounded Soviet soldiers; hundreds of thousands of sick Soviet troops who succumbed to hepatitis, typhoid, and other illnesses; one million dead Afghans; and five million Afghan refugees.

Charlie Wilson watched Gromov cross the bridge on television, then opened a bottle of Dom Pérignon and toasted the Soviet general: “Here’s to you, you motherfucker.”5

Gromov’s red carnations didn’t signal the end of Moscow’s exit strategy in Afghanistan. Instead, the Red Army’s departure triggered a new phase in Soviet-Afghan relations, as Moscow sought cheaper ways to exercise influence. The cornerstone of Gorbachev’s policy was the creation of a viable successor regime in Kabul under Afghan president Mohammad Najibullah.

Without Soviet troops, few gave Najibullah much hope for survival. But Moscow’s withdrawal removed the glue that bound the insurgency together. No longer seeing red, mujahideen factions turned on each other with a vengeance. Najibullah skillfully exploited these divisions and cut deals with local mujahideen commanders. The Afghan president also tried to broaden the regime’s support by downplaying communism, adopting more Islamic customs, and appealing to Afghan nationalism.

To help Najibullah weather the jihadist assault, the Soviet Union left behind huge quantities of ammunition, fuel, and food—topped up by a weekly convoy of six hundred trucks. Backed by Soviet largesse, the Afghan regime proved unexpectedly resilient. Indeed, Najibullah survived longer than the Soviet Union itself. His regime only collapsed in 1992, when Moscow switched off the aid supply.

Najibullah clung on to power, but Afghanistan was left a devastated land with little hope for peace and reconciliation. Two decades later, Afghan hillsides remain littered with rusted Soviet tanks—fossils of a lost dominion.

As Moscow’s experience suggests, the aftermath of withdrawal is a critical part of the surge, talk, and leave exit strategy. The aftermath is no mere epilogue to the main drama. Rather, this is the phase when the political effects of war are consolidated, revised, or entirely overthrown. As the bulk of American soldiers leave the war zone, there’s still much—and perhaps everything—to play for.

Having endured a difficult conflict, Washington may approach the postwar era with trepidation. After all, the consequences of military failure present a litany of challenges, from uniting the American people to helping veterans recover.

But the aftermath of war is not always a time of triumph for the winner—or further decline for the loser. Battlefield success can sometimes be a curse. It may trigger “victory disease,” wherein the winning side sees itself as invincible and pursues ever more ambitious conquests, until disaster ensues. After Japan’s early victories in World War II, for example, Tokyo broadened its horizons across East Asia and became dangerously overextended. Alternatively, battlefield success can represent a Pyrrhic victory at such high cost that it amounts to a loss. When the Greek king Pyrrhus defeated the Romans in 280 BC, he sacrificed so many men he said one more victory would ruin him.

America’s golden-age triumphs sometimes spurred dangerous long-term consequences. Washington’s seizure of territory in the Mexican-American War ultimately deepened sectional divisions in the United States. The capture of the Philippines in the Spanish-American War triggered a bloody counterinsurgency campaign against Filipino nationalists.

Meanwhile, military failure can offer unexpected opportunities for strategic gain. The enemy’s ranks may thin as the winning coalition quarrels over the spoils. And the losing side is often more open to innovation. The searing experience of defeat can overcome entrenched interests, spur creativity, and produce badly needed reform. In the end, stalemate and loss may prove to be just as Pyrrhic as victory.

Let’s look at four different aspects of the aftermath of tough wars: handling enemies, dealing with allies, healing veterans, and shaping historical memory. The thread that ties them together is a search for national renewal. After difficult campaigns, Americans should recover, reflect, and seek to emerge stronger than before.

Making Friends

Nguyen Tan Dung was born in southern Vietnam in 1949. At age twelve, he joined the Vietcong, worked in a medical unit, and was wounded four times. In 1968, not yet twenty years old, Dung served in the Mekong Delta. Fighting on the opposite side in the Mekong Delta at the time was Chuck Hagel, who volunteered for the U.S. Army and won two Purple Hearts.

Half a century later, in 2013, Dung’s and Hagel’s paths crossed again, this time at a conference on security in Singapore. Dung, the prime minister of Vietnam, and Hagel, the U.S. secretary of defense, exchanged war stories. The Vietnamese Communists who once railed against American imperialism now favored a strong U.S. presence in the region to balance a rising China. The American military that once obliterated much of Vietnam now sought a partnership with its former adversary.

How should the United States handle relations with enemies in the aftermath of loss? One answer is what I call divide and woo.

First of all, Washington can exploit fractures in the enemy camp. Indeed, the United States can often foster dissension among adversaries simply by leaving. The Soviet withdrawal from Afghanistan in 1989 triggered divisions among the mujahideen that enabled the Kabul regime to stay in power. In the same vein, the presence of the American military may be the only thing binding the enemy alliance together. The exit of U.S. forces may therefore cause underlying discord to emerge.

During the Vietnam War, the U.S. incursion into Cambodia in 1970 helped forge an alliance between North Vietnam and Cambodia’s leftist insurgency, the Khmer Rouge. But after American troops withdrew from Vietnam and the Khmer Rouge seized power in Cambodia, tensions quickly emerged between the Indochina leftists. In 1978, Vietnam invaded Cambodia and toppled the Khmer Rouge regime. The conflict in Cambodia became Vietnam’s Vietnam War, a counterinsurgency quagmire that lasted over a decade until Hanoi withdrew in 1989.

A similar story played out with China and Vietnam. One of the major reasons for U.S. intervention in the region was the fear that a Communist Vietnam would become a Chinese pawn. But such alarm betrayed a lack of understanding of East Asian history. Vietnam has resisted Chinese influence for two millennia—a narrative celebrated in Hanoi’s National Museum of Vietnamese History. In his book on modern Vietnam, Shadows and Wind, Robert Templer wrote that the fear of Chinese domination “has been constant and has crossed every ideological gap, it has created the brittle sense of anxiety and defensiveness about Vietnamese identity.”6 As one Vietnamese historian put it, “China is always just there, and it will always be dangerous.”7

The American presence in Southeast Asia spurred the very outcome it was designed to avert, an alliance between China and Vietnam. Once American troops left, Communist divisions came to the fore, culminating in China’s invasion of Vietnam in 1979. The Vietnamese fought China with equipment inherited from the United States—ironically fulfilling the weaponry’s original purpose.

As well as splintering its opponents, the United States can also seek to woo them. Reconciliation with enemies is not always possible. Truly extreme adversaries like Al Qaeda may need to be contained or destroyed. But with most opponents, a modus vivendi or even a durable peace is possible. After all, many of Washington’s closest allies were once enemies, like Britain, Mexico, Spain, Italy, Germany, and Japan—not to mention the southern states.

How can enemies become friends? According to political scientist Charles Kupchan, the diplomatic dance begins with a peace offering. Egyptian president Anwar Sadat’s dramatic visit to Jerusalem in 1977, for example, catalyzed the reconciliation process between Egypt and Israel. Next, the former opponents make concessions, and political, economic, and cultural contacts start to grow. Finally, the two sides write new narratives to tell a more positive story about their relationship. Instead of holding the other country responsible for every past conflict, the former enemies place the blame on tragic forces like arms races or mutual misunderstandings.8

Reconciliation between the United States and Vietnam proved to be a hard road. Flush with victory after 1975, Hanoi bungled the process of rapprochement by demanding billions of dollars in “reparations.” Meanwhile, motivated by a mixture of humanitarianism, self-promotion, or material profit, influential Americans propagated the myth that Vietnam was secretly holding U.S. prisoners of war. Finally, in 1995, with the support of Vietnam veterans like John Kerry and John McCain, President Clinton established full diplomatic relations with Hanoi.9

In the twenty-first century, the United States and Vietnam may become close allies. Vietnam fears the colossus to the north far more than the distant United States. China’s population is fifteen times greater than that of Vietnam, and the two countries have a number of maritime border disputes. The United States has only intervened in Vietnam once: China has invaded Vietnam seventeen times. By the 1990s, according to Templer, the American war in Vietnam “was no longer a central feature of life.”10 Three-quarters of Vietnam’s population was born after U.S. soldiers left. And Hanoi has no fear that closer relations will make Vietnam look subservient to Washington. After all, they defeated us.11

The emerging strategic partnership between Washington and Hanoi is founded on a shared interest in checking a rising China. But Vietnam is an increasingly influential player in its own right, with the world’s thirteenth largest population, a rapidly developing economy, and a location close to the South China Sea—the route for nearly 60 percent of Japan’s and Taiwan’s energy supplies and about 80 percent of China’s crude oil imports.

In 2010, Secretary of State Hillary Clinton visited an ASEAN conference in Vietnam and announced that the United States had a “national interest” in the South China Sea and would participate in multilateral efforts to resolve maritime disputes. The United States and Vietnam began joint naval training exercises for the first time since the Vietnam War.12

Tensions remain between Washington and Hanoi over issues like human rights. And both sides are wary of antagonizing China. But the shift in relations is unmistakable. During the 1960s and 1970s, the Vietnam War felt all-consuming. But in the long run, we may see Washington’s conflict with Hanoi as a temporary rivalry that disguised a powerful underlying symmetry of interests.

In 2010, the diplomat Richard Holbrooke recalled visiting Vietnam and being struck by the high-rise buildings named after Western corporations. “A subversive, ironic thought crept into my mind: If General Westmoreland, who had died before these dramatic changes became apparent, were to be suddenly brought back to that very spot, he’d look around and say, ‘By God, we won.’ ”13

If our enemies can be divided or wooed, how should we deal with our allies?

Sesame Garden

One of the all-time great New York Times corrections appeared in 2013. “An earlier version of this article misidentified the ‘Sesame Street’ character with whom Ryan C. Crocker, the former United States ambassador, was photographed in Kabul. It was Grover, not Cookie Monster.”14

What was Ambassador Crocker—once labeled by George W. Bush as “America’s ‘Lawrence of Arabia’ ”—doing in a photo op with Grover? Crocker told me that the State Department wanted to see if any American television shows could be adapted for an Afghan audience, especially for Afghan kids. After some research, it turned out that the Afghans loved Sesame Street. The State Department helped pay for Dari and Pashto versions of the show, which was called Sesame Garden and given an Afghan flavor. The Count character, for example, was cut because Afghan kids hadn’t heard of Dracula and couldn’t understand the fangs. “The new show turned out to be very popular with Afghan kids,” Crocker told me, before stressing “and their parents.”15

Ambassador Crocker pictured with Grover from the Afghan version of Sesame Street in 2011. (U.S. Department of State)

Sesame Garden launched in 2011 and symbolized the boom days of the war effort in Afghanistan, when the United States was spending over $100 billion per year. For a while, no expense was too great. Washington tried to win Afghan hearts and minds with a “stealth rock concert” featuring Australian musician Travis Beard, and a fashion show designed for female empowerment. “At one point,” said a former embassy aide, “we were throwing money at anything with a pulse and a proposal. It was out of control.”16

Once U.S. troops began leaving, the party was over. War weariness and donor fatigue set in, and economic aid to Kabul became a much tougher sell. The American narrative focused on getting the boys home, and Afghans began disappearing from the story. The same administration that tripled U.S. troop levels in 2009 began seriously considering a “zero option” for the American presence after 2014.

The White House eventually settled on a successor force of ten thousand. But these soldiers were given a very narrow mission to train Afghans and hunt Al Qaeda—even though Al Qaeda barely exists in the country. (In November 2014, Obama bowed to military reality by announcing that the successor force could also fight the Taliban, which very much does exist.)

The American successor force will be steadily withdrawn by 2016. Why is this date significant? The answer is not strategic but political: the end of the Obama presidency. The proposed timeline will enable Obama to say he concluded the war before leaving office. However, it may be better for a few thousand troops to stay and train Afghans beyond 2016—even if it complicates Obama’s narrative. In early 2015, Afghan president Ashraf Ghani said that the withdrawal date may need to be reexamined: “Deadlines should not be dogmas.”17

Iraq offers a similar story of declining attention. As long as U.S. soldiers were fighting and dying in Iraq, Washington concentrated intensely on the country. During the surge phase, Iraq was the Bush administration’s top foreign policy issue. In the early months of the Obama administration, the White House continued to prioritize Iraq. Vice President Joe Biden visited Baghdad seven times from 2009 to 2011 and built close relationships with Iraqi leaders. According to one U.S. general, Biden came so frequently he was eligible for Iraqi citizenship.

But when American forces left Iraq in 2011, the country slipped down the White House agenda. The period from 2010 to 2014 was a critical phase in Iraqi politics as the violence worsened dramatically and the gains made during the surge were put at risk. Fighting in Syria seeped into northern Iraq, first in a drip feed of refugees and rebels, and then in a torrent of Islamic State extremists. Meanwhile, efforts to craft a power-sharing deal in Baghdad fell apart, as Prime Minister Maliki pursued a highly sectarian agenda that marginalized Sunnis.

The White House thought the war was over and focused on other issues. From 2011 through early 2015, Biden didn’t visit Iraq. The administration refused to publicly criticize the Iraqi leader. Political commentator Peter Beinart summed up Obama’s policy: “Let Maliki do whatever he wants so long as he keeps Iraq off the front page.”18 A Sunni tribal leader asked, “Where are the Americans? They abandoned us.”19

As these experiences in Afghanistan and Iraq reveal, the United States can act in wartime like a capricious paramour whose interest in the fate of its partner lurches from obsession to neglect. During the escalation phase, we may seek to transform our ally into a dream companion, by writing blank checks for a massive and even disproportionate war effort. But when American soldiers depart, our interest in the ally’s fate dissipates like a fading romance. We look at our watches desperate to leave. We become almost narcissistic, overwhelmingly concerned with getting U.S. troops home. The locals are now objects that we maneuver around to withdraw. We start nickel-and-diming the mission. Congress would rather spend $100 billion funding American troops than $10 billion paying for indigenous soldiers. It’s not our problem anymore.

We need to replace these dramatic swings in American attention with a smoother arc of intervention. This means fighting for less expansive goals early on and pursuing an enduring strategic partnership later on. After all, withdrawal is about removing the bulk of U.S. troops, not abjuring responsibility.

What should our relationship with allies look like in the aftermath of war? Of course, if most U.S. soldiers leave the war zone, our leverage is much reduced. We couldn’t force Baghdad to reconcile with Sunni opponents when 150,000 American troops occupied Iraq, and we can’t impose a settlement with almost zero boots on the ground. Still, we can at least avoid switching off attention. And as opportunities arise, we can use our influence to encourage political compromise and the creation of effective and nonsectarian institutions.20

One of our key tools is economic and military aid. The international community, for example, has made a number of commitments to Afghanistan. At Chicago in 2012, NATO countries pledged to help Kabul pay the estimated $4.1 billion annual cost of the Afghan National Security Forces. And at Tokyo in 2012, the United States and its allies pledged $16 billion in civilian aid over four years.

Is it smart to continue channeling assistance to Kabul? Money for development projects can end up enriching a local elite, spurring more corruption, or lining the pockets of Western expatriates—just look at the fleets of Land Rovers in Kabul. Over the last decade, Western governments and private philanthropists have poured tens of billions of dollars into Afghanistan but the country remains one of the five or so poorest states in the world.

You can count former assistant secretary of state John Hillen among the critics. “So much of it is a waste,” he told me. “We didn’t even put the Buddhas back together.” In 2001, the Taliban spent weeks systematically destroying the huge carved Buddhas of Bamiyan using dynamite, artillery, anti-aircraft guns, and anti-tank mines. After a decade of talk about rebuilding the statues, the reconstruction project has barely got off the ground. For Hillen, it’s a symbolic failure: The return on investment from most aid programs is unimpressive.21

Dov Zakheim worked as the Pentagon’s coordinator for civilian reconstruction in Afghanistan during the Bush administration. Much of the foreign aid effort, he told me, was woefully mismanaged. “We know it’s stupid,” but we keep spending big on complex systems that can’t be maintained and end up rotting.22 The Kajaki Dam in Helmand Province is the dam to nowhere. An ambitious project to rebuild the turbines was designed to win hearts and minds in the Taliban homeland. But the enterprise is years behind schedule due to mismanagement and insurgent attacks.23

Economic aid, however, can play an important role after American troops leave. Although Afghanistan remains one of the most impoverished countries, the last decade has seen a major improvement in the health and education of ordinary Afghans.24 Rather than waste money on big-name projects, we should think small. Carter Malkasian, an advisor to the U.S. military on counterinsurgency, described the National Solidarity Program as “the crown jewel of development in Afghanistan.”25 The program gives relatively modest grants to local village councils to create schools and other infrastructure. We can also step up aid for Afghan agriculture. Most Afghan men of working age are small-scale farmers. They need high-quality seeds and agricultural equipment, advice on yields, and new roads. In all these cases, we should carefully evaluate the efficacy of programs and monitor contracts to reduce corruption.26

In the long run, the answer is trade rather than aid. At the moment, Afghanistan’s biggest export is illegal opium. Indeed, opium production reached a record high in 2013. There are many challenges in extricating the United States from the Afghanistan War, but the most Sisyphean is trying to end opium production. Eradication programs run headlong into market forces; poppies produce far more revenue than other crops like wheat. Fighting a drug war while simultaneously fighting the Taliban is a fool’s errand, which will only serve to lose the support of rural Afghans.

Reducing opium production will take decades of development. We should encourage international investment in Afghanistan and lift trade barriers for Afghan goods to enter the U.S. market. Stepping up U.S. imports of Afghan pomegranates and pistachios might do more good than simply opening the American checkbook. The economic future of Afghanistan could hinge on exploiting the one trillion dollars or more of natural resources in the country, including gold, copper, lithium, coal, gemstones, oil, and gas.

What about military aid? As we saw with Najibullah’s fate after 1989, military assistance can have a big impact on regime survival in a country like Afghanistan. We need clarity about U.S. commitments in Afghanistan until the end of the decade. In a counterinsurgency war, uncertainty about foreign support can be deadly because it saps confidence. This means building on the pledges made at Chicago and guaranteeing funding for the Afghan army for at least the next five years. The Taliban today are weaker than the Soviet-era mujahideen. If we pay for the Afghan army, Kabul can probably hold most of the country. But Kabul’s own revenues can only sustain a small fraction of the Afghan security forces. If funding is slashed, the Afghan army may wither on the vine and the country could descend into chaos—shifting the entire war effort from stalemate to defeat.27

Homeward Bound

War changes people. In 2010, the British photographer Lalage Snow spent eight months taking portraits of British soldiers before, during, and after their deployments in Afghanistan. In a project called We Are The Not Dead, these portraits formed striking triptychs that captured a grueling tour of duty. Men’s and women’s faces became toughened, gaunt, and worn by the hot sun. The secret is in their eyes: sometimes lost, sometimes fixed and intense.28

Handling the aftermath of war requires dealing with the psychological as well as the physical wreckage of conflict. It means caring for veterans, or “for him who shall have borne the battle and for his widow and his orphan,” as Lincoln put it in his second inaugural address.29 Helping returning soldiers is an essential part of the surge, talk, and leave exit strategy. It’s the moral thing to do—and it’s also good policy. A veteran’s struggle to readjust to the home front can ripple outward into the lives of friends and family. Positive treatment of veterans can also help manage the narrative of war and soften the impression of complete failure.

Most of the nation’s 22 million veterans (including more than 2.5 million men and women who served in Iraq, Afghanistan, and other battlefields in the war on terror) reacclimatized successfully to civilian life. But many veterans face a painful struggle, which psychiatrist Jonathan Shay compared to Odysseus’s journey home after the Trojan War.30 Male veterans, for example, are about twice as likely to die of suicide as their civilian counterparts.31

Veterans from dark-age wars may encounter particular challenges in returning home. The U.S. military was not configured for prolonged counterinsurgency campaigns in Afghanistan and Iraq. The result was extended deployments, multiple tours, and shorter rest periods. Soldiers had to deal with mass graves, improvised explosive devices, and pulling their injured buddies out of Humvees.32

In recent wars, veterans have rarely enjoyed the solace of victory. After a military fiasco, it may be more difficult to readjust to civilian life because the public sees the war as a mistake. What did I fight for?

And veterans from dark-age wars can also feel isolated. Wars of national survival mobilize the whole population. In World War II, about 9 percent of Americans were on active military duty at any one time. But the figure for Afghanistan and Iraq is less than 1 percent. The vast majority of Americans haven’t served and can’t fully relate to the veterans’ experiences.

Chris Kyle was one of America’s top snipers in Iraq, with 160 confirmed kills. The Iraqi insurgents called him the Devil of Ramadi. In 2013, Kyle took a fellow Iraq War veteran, Eddie Ray Routh, to a gun range in Texas to help him deal with symptoms associated with post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD). Kyle was shot dead and Routh later confessed to the killing. Routh’s dad said the Iraq War changed his son: “When he gets back I ain’t got my son no more. I got a body that looks like my son.”33

PTSD is the signature affliction of the dark age of American warfare (along with traumatic brain injury). It’s an anxiety disorder caused by traumatic events involving injury or death. Symptoms may include sleep deprivation, flashbacks, withdrawal from emotional attachment, diminished trust in others, a sense of purposelessness, and hypervigilance. PTSD can impair work prospects, destroy relationships, and raise the risk of alcohol or drug abuse and suicide.34

PTSD is probably as old as war itself. It used to go by many names: combat stress, shell shock, soldier’s heart, or battle fatigue. In 1980, the American Psychiatric Association formally recognized PTSD as a disorder. According to RAND, 14 percent of Afghanistan and Iraq War veterans suffered from PTSD (other estimates range from 5 to 15 percent).35

The disorder symbolizes America’s struggles in the new era of civil wars. Just as counterinsurgency is a battle against an enemy we can’t see, so PTSD is a fight to overcome invisible wounds: a shadow illness for a shadow war.

As a country, we’re failing to deal with the problem of PTSD. There’s a gap between our bumper-sticker “support the troops” mentality and our willingness to face up to the true price of war. RAND found that “the majority of individuals with a need for services had not received minimally adequate care.”36

Veterans may be reluctant to seek help for mental health issues, for example, because of fears about confidentiality. Other problems lie with health care provision. The Veterans Affairs medical system, a vast network of 171 medical centers and 350 clinics, does a great deal of good work. In larger metropolitan areas, the VA is at the forefront of treatment for PTSD. But the VA system has come under strain from recent wars. Around fifty thousand Americans were wounded in Iraq and Afghanistan but the VA has treated over two hundred thousand people for PTSD. The VA is also famously slow and bureaucratic in deciding whether to cover a particular claim. And the quality of treatment is inconsistent. Routh, for example, didn’t receive appropriate care in the weeks before he shot Kyle. In May 2014, Eric Shinseki, the secretary of the Department of Veterans Affairs, resigned following a scandal over chronic waiting times at VA hospitals.

There are no easy answers. PTSD is a complex condition that depends on an individual’s psychological makeup and experiences. Each soldier needs a personal exit strategy from war. Several treatments have proven to be consistently effective. Exposure therapy, for example, habituates veterans to the experience of trauma by recounting past events in great detail, helping to adjust people’s emotional response. Meanwhile, cognitive processing therapy enables veterans to become more aware of their thoughts and feelings, which reduces cognitive errors (like the belief that all people are essentially evil) and encourages a more balanced view of the world.37 According to psychiatrist Matthew Friedman, with these evidence-based practices, “complete remission can be achieved in 30–50 percent of cases of PTSD, and partial improvement can be expected with most patients.”38

We need an increased number of trained mental health professionals to provide these treatments in a timely and effective manner. Therapy is expensive but it quickly pays for itself through improved productivity and a reduced risk of suicide and other problems.

We must also enhance funding for wider kinds of distress. PTSD has captured the national limelight, but other psychological problems are also part of the wreckage of war. Depression, for example, affects 2–10 percent of returning veterans. Indeed, the focus on PTSD means that some veterans end up being misdiagnosed and given the wrong treatment.39

By definition, veterans are the lucky ones: the not dead. But some of them return from the darkness, not to a civilian light, but into a kind of twilight world, still bearing the visible and invisible wounds of war. Many soldiers feel isolated after severing the deep bond they had with their buddies and their unit. As David Finkel wrote in his book Thank You for Your Service, “It is such a lonely life, this life afterward.”40 Much of the healing comes from the fellowship of other veterans—from those who really understand and can help find new ways of contributing to society. “Recovery happens only in community,” Jonathan Shay wrote of the veteran’s odyssey.41

That July Afternoon

“For every Southern boy fourteen years old,” wrote William Faulkner, “not once but whenever he wants it, there is the instant when it’s still not yet two o’clock on that July afternoon in 1863.”42 The moments before Major General George Pickett’s futile charge on Union lines at Gettysburg, when Confederate victory was still possible, are seared into Southern memory and folklore.

The century from 1846 to 1945 was the golden age of American warfare—but this wasn’t true for all Americans. Southerners knew the meaning of loss. In 1865, the Confederacy was a devastated land. The entire slave society had collapsed. Half the Southern white men of military age were dead or maimed.

As Southerners tried to make sense of this cataclysm, they discovered the trauma of remembrance. For decades, Southerners found that historical loss has a wounding presentness. One of Faulkner’s characters says in Requiem for a Nun, “The past is never dead. It’s not even past.”43 After the initial shock of defeat subsided, the unbearable question remained: Why had this catastrophe been inflicted on God’s people?

After 1945, the experience of loss became a national, rather than just a regional, phenomenon. Now all Americans were forced to sift through the ashes of failure and deal with painful memories of military fiascos. For a democracy like the United States, the recollection of past debacles cuts particularly close to the bone. We can’t write off battlefield loss as the folly of a misguided Caesar. The fault is in ourselves.

Yesterday’s war is a story we tell each other. Through speeches, books, films, and memorials, we assemble, disassemble, reassemble, and dissemble history. Narratives of conflict are constantly in flux as new information emerges, and we view old facts in the light of present-day concerns.44

Our collective memory of war is critical because it shapes the lessons we draw for future policy. And how we recall military loss is especially important because we usually learn much more from past failures than from successes. Psychologists have identified a “negativity bias” in the human mind where “bad is stronger than good.” According to psychologist Roy Baumeister and colleagues, “bad things will produce larger, more consistent, more multifaceted, or more lasting effects than good things.”45 People process memories of failure in more complex ways than memories of success and reflect more carefully on the causes of negative events. “Prosperity is easily received as our due, and few questions are asked concerning its cause or author,” observed philosopher David Hume. “On the other hand, every disastrous accident alarms us, and sets us on enquiries concerning the principles whence it arose.”46

The experience of military loss is often burned into a nation’s consciousness. One of the major cultural touchstones for Serbs today is their defeat in the battle of Kosovo—even though it happened in 1389. Meanwhile, the foundational event in modern German and Japanese identity is the Götterdämmerung of 1945.

How should we recall difficult wars? In the wake of battlefield failure, the United States can fall prey to a kind of national post-traumatic stress disorder, with significant impairment to functioning. Americans may adopt unhealthy forms of remembrance, including amnesia, phobia, and dangerous myths—and sometimes all three maladies at the same time.

The first hazard is amnesia, when we repress memories of loss and fail to learn the tough lessons about war. We sign on to a national pact of forgetting. Following an intense focus on violence and bloodshed, people often want to think about anything other than the conflict. It’s precisely because failure looms so large in our minds that we try to avoid painful memories.

Korea is often called the “forgotten war”—although it’s not clear if Americans ever really understood what the conflict was about. Journalist David Halberstam said that Americans “preferred to know as little as possible” about the campaign.47 The complex nature of the struggle as both a superpower proxy conflict and a civil war between Koreans, the attritional fighting, and Washington’s decision not to strive for victory proved confusing for a generation of Americans used to winning decisive good-versus-evil contests. “The Korean War, more than any other war in modern times,” wrote historian Bruce Cumings, “is surrounded by residues and slippages of memory.… There is less a presence than an absence.”48

Many Americans also preferred to forget about the Vietnam War. After the fall of Saigon, President Ford urged his fellow citizens to avoid “refighting a war that is finished—as far as America is concerned.”49 Henry Kissinger, the secretary of state, said, “We should never have been there at all. But it’s history.”50 According to journalist Martha Gellhorn, “consensual amnesia was the American reaction, an almost instant reaction, to the Vietnam War.”51

The U.S. military tried especially hard to put Vietnam out of its mind. Chasing the Vietcong was a terrible mistake never to be repeated. Rather than institutionalize the hard-won lessons of guerrilla war, the U.S. Army destroyed all the material on counterinsurgency held at the special warfare school at Fort Bragg. As a result, the military was unprepared for stabilizing Afghanistan and Iraq.52

The Iraq War also slipped from memory. In 2013, the ten-year anniversary of the beginning of the conflict was greeted mainly by silence. Obama rose to the presidency in large part because of his opposition to the Iraq War. But he marked the anniversary by issuing a brief 275-word statement, of which 240 words praised American veterans and a total of 35 words were about Iraq and the Iraqi people.53

Afghanistan is already being labeled a “forgotten war.” Many Americans have mentally checked out. Tough questions are being ignored. Will we leave behind a deeply dysfunctional state? Is the best outcome a military stalemate or a deal with those who once harbored Al Qaeda? What does the deterioration of the war effort say about the future of American global leadership?

Amnesia can be a useful coping strategy. Nietzsche said that forgetting allows us “to close the doors and windows of consciousness for a time.” Putting events out of our mind is “like a doorkeeper, a preserver of psychic order, repose, and etiquette.”54

But expunging a negative experience of American conflict is not a long-term solution. We need to reckon with the bleak side of our nation’s past. Otherwise, we will repeat our mistakes.

The second risk is phobia, where we fixate on past events and try to avoid copying the experience at all costs. Traumatic occurrences can burn a “never again” syndrome into the national psyche. This is the opposite response to amnesia: hyperlearning rather than forgetting.

Phobia can produce a knee-jerk opposition to anything resembling the painful experience. Mark Twain said of a cat that sits on a hot stove top, “She will never sit down on a hot stove-lid again—and that is well; but also she will never sit down on a cold one anymore.”55

Having been burned once in war, the United States may refuse to engage in any similar experience—even if it’s necessary to protect our interests and values. We may also see everything associated with the bad war as tainted, when some aspects of the campaign were actually quite successful and should be copied.

A phobia means we won’t make the same mistake; instead, we could make the opposite mistake. During the humanitarian intervention in Somalia in 1992–94, forty-three Americans died. It was a fairly minor tally by historical standards. And the overall mission succeeded in saving tens of thousands of Somali lives. But for many Americans, Somalia encouraged a phobia about humanitarian intervention. Memories of Somalia were a critical reason why the United States failed to stop the Rwandan genocide in 1994. The ghosts of Mogadishu ensured the rescuer was nowhere in sight.56

Today, Americans are desperate to avoid a repeat of the scarring experience in Iraq and Afghanistan. The dictate “no more Iraqs and Afghanistans” has shaped almost every aspect of Obama’s foreign policy, from the narrative of extrication from Middle Eastern wars to the “pivot” to the Pacific; from the preference for multilateralism in conflicts like Libya in 2011 to the repugnance for nation-building.

The desire not to copy past errors could spur a healthy concern about wading into foreign civil wars. But the siren song of “not Iraq” could also lead the United States into a damaging retreat from global leadership. The scholar Lawrence Freedman described the Iraq syndrome as a “renewed, nagging and sometimes paralyzing belief that any large-scale U.S. military intervention abroad is doomed to practical failure and moral iniquity.”57

If we have a phobic reaction to bad wars, why does the United States end up repeating the experience—like counterinsurgency in Vietnam, Afghanistan, and Iraq? Psychological dread can actually trigger a recurrence of the negative events. The George W. Bush administration was extremely hostile to prolonged Vietnam-style nation-building and invaded Iraq with a small footprint designed to allow a speedy exit. But the lack of American troops produced chronic insecurity and exactly the kind of drawn-out quagmire that Bush sought to avoid.

The third harmful memory of loss is dangerous myths, where we learn pernicious lessons about the past. After the American Civil War, Southerners embraced the myth of the “Lost Cause” to make sense of their catastrophic defeat. According to this legend, the South won a moral victory through superior gallantry, heroism, and skill, but was ultimately ground down by greater numbers, industrial might, and brutal warfare. Although the South deserved to win, so the myth goes, its defeat was ultimately for the good of mankind.

The Lost Cause narrative helped reconcile the South to defeat and reunion. “Because I love the South,” said Woodrow Wilson in 1880, “I rejoice in the failure of the Confederacy.”58 But the story of national rapprochement excluded blacks. The Lost Cause was a white man’s tale. Memories of the Civil War highlighted glory and sacrifice rather than emancipation and race. Black human rights became another lost cause as a new apartheid system emerged in the Southern states. In 1913, during the fiftieth anniversary of Gettysburg, white Union and Confederate veterans joined hands in friendship, but black veterans were not allowed to participate.

Another dangerous myth is the “stab in the back”—or blaming domestic opponents for the military loss. Following the fall of Saigon, Nixon held liberals, Congress, and the media responsible for snatching defeat from the jaws of victory. Scapegoating the enemy within deepened the social divisions from the war.59

The answer is not amnesia, phobia, or dangerous myths; it’s renewal. Americans should craft a narrative of the past that confronts the hard truths of war while ultimately helping the country come to terms with its experience.

White Northern and Southern veterans reconcile in 1913 during the 50th anniversary of Gettysburg. (Library of Congress, LC-DIG-ppmsca-32660)

After all, failure is a priceless opportunity to learn and adapt. People, institutions, and countries are often averse to change. To alter the system, you need a shock to the system—and the most powerful shock is losing.

In the 1980s, sportswriter Bill James found that baseball teams that improved in one year tended to decline in subsequent years, whereas teams that did poorly often made a comeback. Failing sides were more willing to innovate. “There develop over time separate and unequal strategies adopted by winners and losers; the balance of those strategies favors the losers, and thus serves constantly to narrow the difference between the two.”60

In the same vein, winners in war may succumb to enervation and complacency, whereas losers are more open to creative thinking. The experience of stalemate or defeat can overcome vested interests and produce necessary change. During the decades after World War I, for example, the victorious powers of Britain and France believed that the next war would be much like the last and developed a defensive doctrine based on fortifications like the ill-fated Maginot Line. By contrast, the losing country, Germany, embraced reform. Berlin engaged in a root-and-branch critique of its failure in the Great War and ultimately developed a new doctrine of armored warfare known as blitzkrieg.

Winning sports teams accept their losses and study the game tapes to avoid a repeat performance. We should approach past failure with a similar spirit of confidence and humility. This means not gilding the war effort, but instead taking responsibility for our actions, including war crimes and other abuses. It means identifying the things we got right—even if the overall campaign was a failure. And it means accepting the complexity of past wars, the context-specific nature of historical “lessons,” and the danger of simplistic instruction.

In the next chapter, we’ll look more closely at Korea, Vietnam, Iraq, and Afghanistan as teachable moments and discover how to start winning wars again. But before we do that, let’s take a step back and summarize what we’ve learned so far.

Surge, Talk, and Leave

We live in the dark age of American warfare when most major conflicts end in regret. After 1945, the collision between U.S. power and a changed battlefield environment triggered seven decades of stalemate and loss. The nation’s newfound strength encouraged an interventionist impulse, just as the locus of conflict shifted from interstate war to civil war, throwing the U.S. military off balance.

The United States began battling in distant lands against culturally alien foes it didn’t understand. And the enemy usually had much more at stake in the fight. Washington was stuck using a golden-age playbook of conventional warfare and failed to adapt to the new era of counterinsurgency. By contrast, guerrillas raised their game by seizing the banner of nationalism, adapting to American weaknesses, and seeking outside sources of support. As a result, U.S. wars repeatedly degenerated into fiascos, or unwinnable conflicts where victory was no longer realistic.

Time and again, in the face of battlefield loss, the United States miscalculated and made a poor situation even worse. Sometimes we waded further into the mire like in Vietnam. In other conflicts, we tried to exit too hastily like in Iraq. We failed to revise our war aims effectively. We waited too long to talk to the adversary and then adopted an intransigent stance in negotiations. As the U.S. war effort peaked and declined, we tended to lurch from an obsessive concern with the ally’s fate to a narcissistic focus on getting Americans home. Presidents were not always candid with Congress or the American people, deepening divisions on the home front.

What’s the answer? First of all, we must realize that the outcome of war is not a binary like victory or defeat—where only victory is tolerable. Instead, the result lies on a spectrum with many gradations of success and failure. Achieving a draw rather than a catastrophic loss may be a profile in courage that saves thousands of American and allied lives.

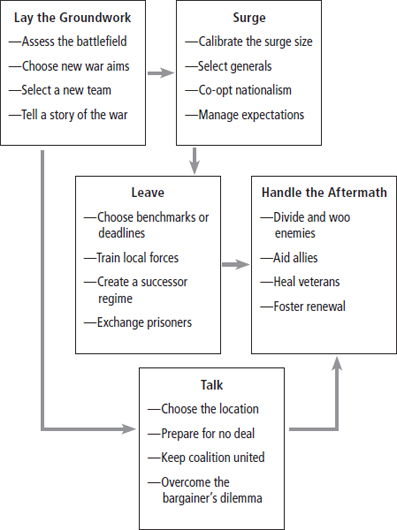

When a war becomes unwinnable, we need an exit strategy rather than exit tactics. We must step back, assess the terrain, and craft a long-term plan, rather than putting out fires one by one. The exit strategy should be surge, talk, and leave. Washington sends additional forces, negotiates with the adversary, and then withdraws the bulk of American troops. The surge averts immediate battlefield disaster and helps the United States achieve a revised set of goals. Diplomacy delivers a tolerable negotiated deal. And U.S. forces leave with a clear plan for the political succession. Then, in the aftermath of war, we divide and woo adversaries, optimize the level of aid to allies, heal veterans, and foster national renewal.

Meanwhile, the president should tell a story of the war to rally support at home and abroad. The White House must keep expectations in check, pay attention to the symbolism of peace talks, overcome the bargainer’s dilemma, manage the optics of the final act, and shape the way we remember and learn from war.

Surge, talk, and leave creates a bell curve of U.S. troop strength that rises and declines. The shape of the curve will vary greatly depending on the overall objectives. If the United States pursues limited surgical strike aims, the arc may feature a relatively small surge and a quick withdrawal. By contrast, if Washington seeks to build a beacon of freedom, the curve may show a significant escalation followed by a slow drawdown of troops over many years.

Other dynamics can also shape the curve. If the United States faces a severe immediate crisis but pursues restricted goals, there could be a sharp increase in troop levels followed by a rapid decrease. Alternatively, if the battlefield crisis is contained, but training local soldiers will be time consuming, the curve may be flatter and longer, with a smaller expansion of force strength and a more prolonged withdrawal.61

The different elements of the surge, talk, and leave exit strategy are designed to be mutually reinforcing. First, a military fiasco implies that Washington has too few capabilities to achieve its objectives. Dialing down the goals and surging the resources can bring the ends and means into alignment—which is necessary for a successful strategy. During the surge phase in Iraq, for example, Washington scaled down its aims to “sustainable stability” and boosted U.S. troop levels, producing a much closer match between the aims and the capabilities.

Second, the surge can help the United States talk more effectively to the enemy. By eroding the opponent’s military strength, we may make gains at the diplomatic table. U.S. reinforcements can also boost America’s no-deal world and weaken the enemy’s no-deal world, thereby improving our bargaining leverage. And new soldiers can protect rebels who want to defect.

Third, the surge can aid the process of leaving by facilitating efforts to train and advise indigenous forces. These programs often require large numbers of American soldiers to live and work with local allies. As part of the surge in Iraq, for example, Washington significantly expanded its training programs for Iraqi army and police forces.62

There are potential vulnerabilities, however, with surge, talk, and leave. For one thing, the act of leaving may undermine the narrative of the campaign. The answer is to tell a story that moderates expectations, solves the bargainer’s dilemma, and controls the symbolism of the final acts.

Unless we’re careful, the process of leaving can also diminish the chance of successful talks. If American troops are heading home anyway, why will the opponent bargain? In 1969, American diplomat Henry Cabot Lodge wrote, “To be in a hurry when your opponent is not puts one in a very weak negotiating position.”63

It all depends on how we leave. Training indigenous forces can improve our no-deal world, and therefore our negotiating leverage. And the act of withdrawing can itself be a powerful bargaining chip. The speed of the drawdown and the size of any successor force are all potentially on the table for discussion in peace talks. This is one reason why it’s best to start negotiating with the enemy in parallel with the surge and before a fixed deadline for withdrawal is set.

The surge, talk, and leave exit strategy should be implemented immediately after a fiasco. But what happens if the United States fails to act and the situation gets even worse? Presidents may inherit a war that became a fiasco long before, like Eisenhower in 1953, Nixon in 1969, or Obama in 2009. What happens now?

Just like getting sick and failing to receive appropriate medical attention, waiting too long to address a fiasco complicates the response. There could be further deterioration on the battlefield, more American casualties, deepening domestic division, and additional alliance strains. We may therefore have to adjust the surge, talk, and leave exit strategy and look at starker options of damage limitation. At some point, a surge of American troops may no longer be feasible. By 1969, when Nixon came to power, the time for U.S. reinforcements in Vietnam had long since passed. The onus was now on talking and leaving.

We should also alter the surge, talk, and leave exit strategy mid-course because of changes in the military, political, and economic environment. The withdrawal plan needs a feedback loop. As new information emerges about the military balance and political context, we can reconsider our objectives and alter the troop levels, negotiation strategy, and speed of departure. In other words, we should repeatedly return to the very first task—measuring progress.

Surge, talk, and leave can help the United States limit the damage after battlefield loss. But like any exit strategy from a difficult campaign, it’s tough, painful, and carries a degree of risk. Stumbling from a fiasco, there are no easy choices. Indeed, resolving a failing war may be the single greatest challenge in all of politics—one that proved beyond such skillful leaders as Harry Truman and Lyndon Johnson.

Today, American patience with the war in Afghanistan is almost exhausted. In just four years we went from tripling U.S. troop levels to an unsustainable figure of one hundred thousand to contemplating a minimal successor force or a zero option of complete withdrawal. As U.S. forces leave, we must remain focused on our core goals: preventing a Taliban victory, stopping the return of Al Qaeda, and averting the destabilization of neighboring Pakistan. We should continue to fund the Afghan army, support efforts at a negotiated deal, and tell a meaningful story of the withdrawal for Americans and Afghans.

Looking ahead, future American wars are likely to turn into military fiascos. The combination of U.S. power and a prevalence of civil wars is a recipe for unwinnable conflicts, as Washington is lured into tough foreign campaigns. Are we doomed to a generation of quagmires? Or is it possible to avoid some of these wars, and win those campaigns we do fight?