CHAPTER FIVE

The Faces of Hermes Trismegistus (Iconographic Documents)

Hermes Trismegistus has been an iconographic subject since the dawn of the Renaissance, even before the rediscovery of the texts of the Corpus Hermeticum. He appeared in both Hermetic and alchemical contexts as a figure quite distinct from the alchemical Hermes-Mercury, whose representations fill the numerous treatises on the Great Work illustrated in the seventeenth century

The Middle Ages did not hesitate to represent this Trismegistus. There is, for example, the beautiful book of illuminations dating from the end of the thirteenth or the beginning of the fourteenth century, at the Meermanno-Westreenianum Museum in The Hague (see Plates 1 and 2). This contains a French version of Saint Augustine's City of God, in which the passage that refers to Hermes is illustrated by two miniatures. In the foreground of the first (fol.390) we recognize Jesus and his father; in the background we see the prophet Isaiah, Hermes Trismegistus (who wears a red hat and a blue garment), and Saint Augustine himself. The latter blames Hermes for having described the Egyptian practices that give life to statues with the help of magical formulas and invocations. In so doing, he quotes the relevant passages from the Asclepius and says that Hermes has his prophecies on the decline of Egypt from the Devil and not from God. As an example of a “true prophecy” on the decline of Egyptian idolatry, he quotes Isaiah, 19.1: “An oracle concerning Egypt. Behold, the Lord is riding on a swift cloud and comes to Egypt; and the idols of Egypt will tremble at his presence.” And in Isaiah 19.10: “Those who are the pillars of the land will qe crushed, and all who work for hire will be grieved.” The columns from which the statues topple occupy a big place in both pictures; they also illustrate, of course, the famous passage of the “Lamentation” in Asclepius. On the second illumination (fol.392), the colors of Hermes Trismegistus's garments are bleaker. He sits weeping as the idols topple from their columns and are collected by devout people, while a mass—the symbol of the true, victorious religion—is celebrated. We are reminded here of Isaiah 19.19: “In that day there will be an altar to the Lord in the midst of the land of Egypt, and a pillar to the Lord at its border.”

As far as alchemy is concerned, there are at least three documents from the fifteenth century. We mention first the exquisite illumination in Norton's Ordinall of Alchymy (British Library, Add. Ms. 10,302, fol.33 verso). For a colored reproduction, see Stanislas Klossowski, Alchemy: The Secret Art (London: Thames and Hudson, 1973), fig. 9. This miniature (Plate 3) shows the bearded heads of four great alchemical Masters, each wearing a hat of a different color and flanked by a scroll with a Latin inscription. The first master, Geber, wears a green hat and says: “Tere tere tere iterum terene tedeat” (Grind, grind, and ever grind again without ceasing). The second, Arnold of Villanova (blue hat), adds: “Bibat quantum potest, usque duodenies” (Let it drink as much as it can, up to twelve times). The third is Rhases (yellow hat): “Quotiescumque inbibitur totiens dessicatur” (It must be dried as many times as it was soaked). Lastly Hermes, in a red hat: “Hoc album aese assate et coquite donee faciat seipsum germinare” (Roast this white ore and cook it until it grows of itself). These same motifs were redrawn in a different style for Ashmole's collection of English alchemists in 1652 (see Plate 32).

Our second alchemical illustration from the fifteenth century is the watercolor (Plate 4) that accompanies the Miscellanea di Alchimia preserved in the Biblioteca Medica Laurenziana in Florence. A double, eight-pointed star accompanies the figure, dressed in Oriental. style, who makes a curious gesture with his hands: one finger points upward, those of the other hand downward, as if reminding us of the first verse of the Emerald Tablet, “That which is above is like unto that which is below…”

The third alchemical illustration from the fifteenth century (Plate 5) occurs in a manuscript of Aurora Consurgens with 37 miniatures added to the text (which was not planned with illustration in mind). It is largely a commentary on the Tabula Chemica of Senior, i.e., of Ibn Umail: an Arabic text that was very poorly translated into Latin in the twelfth or thirteenth century. There is a bibliography relating to it in the works of Barbara Obrist and Jacques Van Lennep, and in Julius Ruska, “Studien zu Muhammad Ibn Umail” (see note 35 to Chapter 3). The oldest surviving manuscript of Aurora Consurgens, albeit an incomplete one, was written between 1420 and 1430, and is in Zurich. The very beautiful complete manuscript of circa 1450, from which our illustration comes, is preserved in Prague. The illumination shown here was published in color by Barbara Obrist, and in black and white by Jacques van Lennep (Alchimie: Contribution à l'histoire de l'art alchimique, Credit Communal de Belgique, 1985). It illustrates the prologue of Senior's book, which tells of the finding, in a sort of temple, of a tablet held in the hands of an old man. This prologue relates the tablet to the Emerald Tablet, and explains the symbolic meaning of the birds. As for the text of the Tabula Chemica, it is mainly devoted to the images drawn on this object held by Hermes: purely geometrical figures, without human beings. In this sense, our illustration from the Aurora Consurgens is a novelty, since it shows the whole scenario of the discovery, picturing all the elements of the story, even the birds. An almost identical scenario appears in the Arabic text called the Book of Crates (end of the eighth or beginning of the ninth century), as well as in other ancient manuscripts that describe the discovery of the emerald “table” or tablet in a crypt, a tomb, a pyramid, or a temple, held in Trismegistus's own hands. Some scenarios present the Tablet as a text (e.g., the De principalibus rerum causis); others as a group of figures, as in our Plate 5. This apparently dual tradition of text plus image is in fact a single one; but in the West it is the text that has predominated, to the detriment of the image.

At the base of Plate 5 it says:

Hic jam patet id quod omnibus iis figur is

Ad amico ego dico Senior in Scripturis.

Now is revealed that which, with all these figures,

I, Senior, tell my friend in my writings.

We find this image of Hermes and his tablet surrounded by figures and birds in several other treatises, of which the first published one seems to have been the edition of Senior's Tabula Chemica circa 1560, under the title De Chemia (see Plate 10). This picture was discussed by Athanasius Kircher in his Oedipus Aegyptiacus (Rome, 1653). The copy of De Chemia in the Bibliothèque Nationale in Parls (Inventaire 3305 7) is bound with Ars chemica, quod sit licita of 1566. The image is preceded by the following verses:

Quid Soles, Lunae signent, pictaeve tabellae,

Quid venerandi etiam, proflua barba Senis,

Turba quid astantum, volucrum quid turba volantum,

Antra quid, armati quid pedes usque volent.

Miraris? Veterum sunt haec monumenta Sophorum,

Omnia consignans, iste Libellus habet.

Do you wonder what the Sun and Moon mean, and the pictures of the Tablet; the flowing beard of the venerable old man, the crowd of people standing there, and the host of birds flying; the cave, and what the two armed feet signify? These are monuments of the Ancient Sages. That Book has all these things written on it.

The same artistic motif (see Plate 11) is found in a manuscript containing several water-colors, done in Nuremberg between 1577 and 1583.(also in Van Lennep's Alchimie, p.109). A new printed adaptation of the motif, less expert than the two preceding, appears in Philosophicae Chymicae IV Vetutissima Scripta (Frankfurt, 1605). Later, the Theatrum Chemicum of 1660 (vol. V, p.192) offers an illustration of the same kind, even less attractive and precise. In Manget's Bibliotheca Chemica Curiosa (1702, Vol. II, facingp.216), the drawing has become extremely crude. On this subject, see the commentaries given by J. Ruska in his “Studien” (see above), p.31.

In the context of Hermetism properly so-called, one of the earliest documents is among the 99 drawings executed in Florence in the middle of the fifteenth century or a little after: the Florentine Picture Chronicle of Maso Finiguerra or, rather, by his discliple Bacchio Baldini (see Plate 6). It shows scenes and personages of ancient history, both sacred and profane, grouped on 51 leaves (though it appears that one is missing) and done in sepia, grisaille, and brown. Noteworthy figures preceding Hermes Trismegistus include Adam and Eve, Zoroaster, and Ostanes. Discovered in 1840, this manuscript was published with a critical and descriptive text by Sidney Colvin (London: Bernard Quaritch, 1898). Trismegistus holds aloft something resembling a homunculus, perhaps the one of Albertus Magnus, while a kind of nude Hercules, leaning on his club, seems to look on astonished. The legend simply reads: “Mercurius re di gitto” (Mercury, King of Egypt). The rocky and chaotic ground reminds one of certain paintings of Leonardo da Vinci.

What is probably the best known work appears not in a book but in Siena Cathedral (see Plate 7). It is one of the images engraved between 1481 and 1498 on the white marble floor-slabs, representing the pagan prophets and the five Sibyls considered as precursors of Christianity; as Ficino says: “Lactantius did not hesitate to number [Trismegistus] among the Sibyls and Prophets.” The group in question dates from 1488 and is attributed to Giovanni di Maestro Stephano. Placed in the middle of the floor at the far western end of the building, it immediately seizes the visitor's attention. At the foot it says: “Hermis Mercurius Trismegistus contemporaneus Moysi” (Mercury Trismegistus, contemporary of Moses). In the middle he himself appears, with a long forked beard and a pointed hat or miter, handing to another bearded, turbaned man a book on which one can read the words: “Suscipite o liecteras et leges Egiptii” (Receive your letters and laws, O Egyptians!). His left hand touches a vertical slab supported by sphinxes upon which is carved a passage that summarizes Asclepius I, 8. The passage reads:

Deus omnium creator

Sec[und]um deum fecit

Visibilem et hunc

Fecit primum et solum

Quo oblectatus est et

Vaide amavit proprium

Filium qui appellatur

Sanctum Verbum

God, the creator of all, made himself a second visible god, and made him the first and only one. He rejoiced in him, he greatly loved this his own son, who is called the Holy Word.

Some have wondered whether the other personages symbolize savants of West and East (the one on the left is dressed like a monk); or whether Trismegistus is the one in the turban, thus receiving his teachings from Moses. However, it seems more plausible that the central figure is indeed Trismegistus; in fact, as Cicero recalls in his book on the nature of the gods, it was he “who gave laws apd letters to the Egyptians.” The turbaned man would then be Plato, as Walter Scott suggested in his edition of the Hermetica (vol. I, pp.32f.—see Chapter 6, SB), and the one on the left might well be Marsilio Ficino.

I know of no other, representations from this epoch, but there must certainly be some. The gold medal published by Nowotny is perhaps contemporary, on which is written round the edge: “Hermes Trismegistus philosophus et imperator” (see Cornelius Agrippa, De occulta philosophia, ed. Karl Anton Nowotny, Graz: Akademische Druck-und Verlagsanstalt, 1967: alchemical medal numbered 43).

Should we recognize Trismegistus as one of the three figures of the famous painting by Giorgione—one of the masters of the Venetian School—dating around 1500 and now in the Vienna Staatsgalerie? Here again, we have an old bearded man, holding a manuscript and accompanied by two personages: a turbaned Oriental, and a young, pensive European equipped with square and compasses. The green costume and charming looks of the latter suggest Saint John the Evangelist (compare the illustration by Jean Fouquet in Etienne Chevalier's Book of Hours). The Oriental resembles a picture of an alchemist by Dürer. An X-ray examination of the Giorgione painting has shown that the old man on the right originally wore a diadem with rays, decorated with plumes, such as the ancient Egyptians attributed to the divine scribe, Thoth—here transformed into a mere astrologer. On this painting, see G. F. Hartlaub, “L'ésotérisme de Giorgione (sur un tableau de la Wiener Staatsgalerie),” in La Tour Saint-Jacques, no. 15 (May-June 1958), pp.13-18. Mirko Sladek is preparing a thorough study of this painting.

The first Trismegistus of our series who has as attribute an astrolabe or armillary sphere is found at the Ambrosiana Gallery in Milan (Plate 8). Attributed to the Bamabite Brothers, it dates from the second half of the sixteenth century (previously published in Firenze e la Toscana dei Medici nell Europa del Cinquecento, Catalog of an Exhibition of the Institute and Museum of the History of Science, Florence: Electra Editrice, Centro Di Edizioni Alinari-Scala, 1980). The sphere is placed, with a compass, beneath a table holding books. It seems that this attribute of our character only appears at this epoch, and often afterwards with the compass, as here. Above the bare head of the figure, a single word “Trismegistus” identifies him. The image is drawn in a circle, on which one reads: “God is an intelligible sphere whose center is everywhere and whose circumference is nowhere”—a formula apparently found for the first time in the twelfth-century Liber XXIV philosophorum. (On this book and its fortunes, see Dietrich Mahnke, Unendliche Sphäre und Allmittelpunkt, Halle, 1937; reprinted Stuttgart: F. Fromann, 1966.)

Between 1545 and 1573, the Portuguese artist and humanist Francisco de Holanda completed a superb series of plates entitled De aetatibus mundi imagines (facsimile edition with a study by Jorge Segurado, Lisbon, 1983). One of them (fol. 26 verso/LIII/45) represents the entombment of Moses by angels. Two medallions complete this composition, placed one on each side below it. The left-hand one (see Plate 9) shows Hermes Trismegistus in the foreground, flanked by Cadmus and Bacchus in the background. Hermes puts his finger to his lips in the gesture of Harpocrates, like the Hermes-Mercury of the emblem created in that period by Achilles Bacchi (see his Symbolicae Quaestiones, 1555, Symbol LXII). The other medallion, below and to the right, represents Lusus, Tantalus, and Perseus. For a bibliography of Francisco d'Holanda, see A. Faivre, “Le De aetatibus mundi imagines de Francisco d'Holanda,” in A.R.I.E.S., no. 2 (1984) pp.34-37.

Professor Frans A. Janssen has recently drawn my attention to a painting located in a room of the Vatican Library built in 1581 by Francesco Rainaldi for Pope Sixtus V. This room, the Salone Sistino, is located above the present reading room of the Vatican. It contains a series of painted pillars, each representing the “inventor” of a script and (f an alphabet. These alphabets are depicted above each corresponding “inventor,” and Moses is credited with the invention of Hebrew, Mercurius Thoth with the Egyptian, and so on. The explanatory legends and attributions beneath each of the alphabets are ascribed to Silvio Antoniano and Pietro Galesino, who may have drawn on the studies of Teso Ambrogio and Guillaume Postel. The paintings are ascribed to Luca Horfei. These frescoes belong to the earliest production of the Roman baroque. Soon after the opening of the Library in 1588, three major works were published on the alphabets and their attributions. On the pillar dedicated to Hermes Thoth (see Plates 12A and 12B) we read, inscribed under the character's feet, “Mercurius Thoyt Aegyptiis sacras litteras conscripsit” and above his head an Egyptian alphabet is drawn. He holds the caduceus in his right hand, wears the winged hat, is clad with a white dress, a yellow cloak, a red collar, his belt and breeches are red blue and red. A brooch is affixed on his collar, animals adorn his breeches and a face covered with eyes—therefore identifiable as the head of Argus Panoptes—is painted against his left foot (see Plate 12). On these pillars, and for an extensive bibliography, see The Type Specimen of the Vatican Press 1628, facsimile with an introduction and notes by H. D. L. Vervliet (Amsterdam: Menno Hertzberger, 1967), pp. 16-21.

Coming now to the seventeenth century, we begin with the great mythological and emblematic work published at Oppenheim: De divinatione et magicis praestigiis (see Plate 13). Undated, it comes from the first years of the century and is illustrated by Johann Theodor de Bry, the engraver of numerous plates for Robert Fludd and Michael Maier. The author of the work, Jean-Jacques Boissard, devotes a whole chapter to Hermes Trismegistus, opening with this finely detailed engraving, giving him as attributes an armillary sphere, military trophies, and also—a rare occurrence—a caduceus, to emphasize his kinship with Hermes-Mercury.

An exactly contemporary work (Plate 14), done carelessly as a rapid sketch, scarcely figurative, comes in the work of Giovambatista Birelli: Opere. Toro prima. Nel qual si tratta dell'Alchimia, suoi mambri, utili, curiosi, et dilettevoli. Con la vita d'Ermete, Florence, 1601, p.SSl. The “life of Hermes” promised in the title occupies no more than a small page.

Still from the beginning of the century, the title page (Plate 15) of Andreas Libavius's D.O.M.A. Alchymia Andreae Libavii, recognita, emendata, et aucta (1606), shows Trismegistus accompanied by Hippocrates, Aristotle, and Galen; but none of these is much distinguished from the others by precise attributes. It is one of the first images in which Hermes Trismegistus appears in the company of other personages, assembled in a single tableau with the intent of creating a “monumental” impression (in the etymological sense). This picture is also reproduced as the title page of Libavius's Syntagmata, published at Frankfurt in 1611.

The opening page (Plate 16) of the preface of Joachim Tancke's Promptuarium Alchemiae, vol. I (Leipzig, 1610; facsimile edition with notes and commentaries by Karl R. H. Frick, 2 vols., Graz: Akademische Druck- und Verlagsanstalt, 1976) belongs to the same stylistic current then in formation, failing to give our personage his characteristics and only showing him in schematic form, alongside Geber, Bernard of Trevisan, and Paracelsus. The very elaborate title page (Plate 18) of Oswald Croll's Basilica Chymica (Frankfurt, n.d., but dated 1611 in the Duveen catalogue by Kraus) represents Hermes in the company of Morienus, Lull, Geber, and Roger Bacon. The book and its illustration were reissued several times.

This style in question becomes more precise with Michael Maier (see Plate 17), whose work Symbola aureae mensae duodecim nationum (Frankfurt, 1617) came from the atelier of Lucas Jennis. A chapter entirely dedicated to Trismegistus opens with an elegant engraving showing the sage holding an armillary sphere in one hand, and with the other pointing to the sun and moon enveloped in circles of fire. One has the impression here that this personage and Hermes-Mercury are one and the same. In the same work, Maier presents twelve sages who speak in tum, after the fashion of the Turba, i.e., the “Assemblies” of Hermetic philosophers. Thus on the title page (Plate 19), re-used in the Musaeum Hermeticum of 1625 to illustrate another book, “Hermes the Egyptian” is in the place of honor beside Maria the Jewess. One meets him again, face-to-face with Virgil (Plate 20), in a collection of Paracelsus's writings by Johann Huser(Strasburg, 160S; reprint, 1618). The Baroque style of this frontispiece brings out its monumental aspect.

Daniel Stolzius von Stolzenberg, who was practically of the same school as Maier, reproduced our Plate 16 without modification in his Viridarium Chemicum (Frankfurt, 1624; Latin and German edition, in which figs. XVIff. are the same as in Maier's Symbola). The title page of the book (Plate 21) is flanked by two statues on plinths, Trismegistus and Paracelsus. On these publications, see the postface by Ferdinand Weinhandl to Stolzius's Chymisches Lustgarten (Darmstadt: Wissenschaftliche Buchgesellschaft, 1964), and especially the edition of Viridarium chymicum ou le Jardin chymique with preface, introduction, translation, and commentaries by Bernard Husson (Paris: Librairie des Medicis, 1975), which is very well documented. In his Hortulus Hermeticus flosculis philosophorum cupro incisis conformatus…(Frankfurt, 1627, reissued in Manget, vol. II, pp.895ff.), this same Stolzius presents 136 authors and anonymous writers illustrative of the history of alchemy in the form of emblematic medallions (Plate 22). The first of this list is Trismegistus, of whom one can see nothing but a hand emerging from a cloud and holding the armillary sphere. These medallions are actually by Johann Daniel Mylius: they appeared for the first time in 1618, in the third treatise of his Opus medico-chymicum, entitled Basilica philosophica.

Trismegistus shares the title page of Hydrolithus Sophicus seu Aquarium Sapientum (Plate 23) with Galen, Morienus, Lull, Roger Bacon, and Paracelsus. The author of this work is Johann A. Siebmacher (see J. Ferguson, Bibliotheca Chimica, vol. II, p.383). The title page in question had already appeared in 1620 in Frankfurt, as a frontispiece to Johann Daniel Mylius's Operis medico-chymica pars altera, naturally with a different title in the central panel. Trismegistus is with Hippocrates, Geber, and Aristotle on the title (Plate 24) of the Pharmacopoea restituta of Josephus Quercetanus (alias Joseph Duchesne or Du Chesne), Strasburg, 1625. And he faces Hippocrates (Plate 25) on that of the Via Veritatis Unicae in the first edition of the Musaeum Hermeticum (1625, but absent from the best-known edition, that of 1677. Cf. reprint with introduction by Karl R. H. Frick, Graz: Akademische Druck- und Verlagsanstalt, 1970). Hippocrates accompanies Trismegistus once again, with the allegorical figures of Diligence and Experience (Plate 26), in the Thesaurus of Hadrianus a Mynsicht (alias Hanias Madathanus, his real name being Seumenicht), which appeared at Liibeck in 1638 and was several times reissued (e.g., in 1675 at Frankfurt).

Trismegistus's companion is Basil Valentine in the Traité de l'eau de vie (1646) of Brouaut, with its beautiful title page (Plate 27): the only work, so far as I know, in which Trismegistus has as attributes, besides the armillary sphere, both laboratory and musical instruments (a viola da gamba, and seven organ pipes corresponding to the planets). The inscriptions read: “Psallite Domino in Chordis et organo” (Sing unto God with strings and organ)—“Hermes Trismegistus Orientalis Ph[ilosoph]us” (Hermes Trismegistus, the Oriental Philosopher)—“Harmonia Sancta, spirituum malignorum fuga seu [Saturn] intemperiei Medicina est” (Sacred Harmony puts to flight evil spirits and is the Medicine of the intemperate [Saturn]). This engraving was reused in Basile Valentine, Révélation des mysteres des teintures essentielles des sept metaux (Paris, 1668). A commentary on it appears in Eugène Canseliet, Deux Logis alchimiques (Paris: Pauvert, 1979), pp.237-24l.

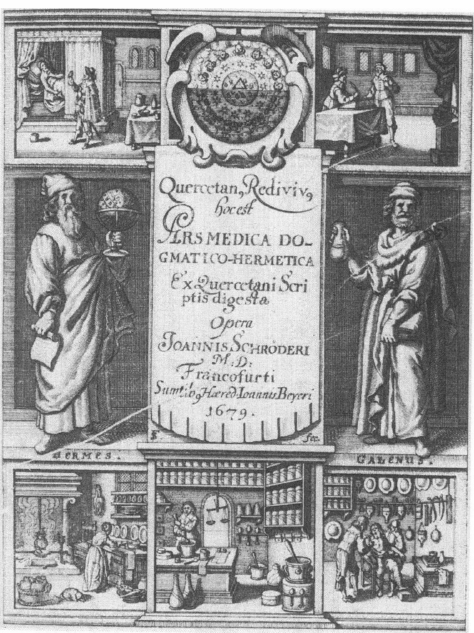

On the Pharmacopoeia Augustana of 1646, Trismegistus carries the text of the Emerald Tablet written on a scroll and faces Hippocrates (Plate 28). It is Hippocrates, Galen, and Aristotle who accompany Hermes (Plate 29) in the Recueil des plus curieux et rares secrets (1648), a collection of various works by Joseph Duchesne, alias Quercetanus. This elegant title page was engraved by Michel Van Lochen in 1641. The frontispiece of Ars Medica (Plate 30), another posthum9us edition of Quercetanus's works, shows Hermes Trismegistus opposite Galen, together with several drawings inside squares that illustrate the medical art.

This style of presentation, with multiple emblematic personages or scenes, is quite common in this period: among the best known examples is the frontispiece of Robert Burton's Anatomy of Melancholy (Oxford, 1628). A simplified version of the pattern (Plate 31) appears in the treatise of Rhumelius, Medicina Spagyrica (Frankfurt, 1648), with Hermes Trismegistus standing opposite Arnold of Villanova. Beneath Hermes is a sick room; beneath Arnold, an apothecary's shop. At bottom center is a kind of athanor; at top center, a dove descends from heaven to earth, where two serpents arise.

In 1652 a modernized version of the fifteenth-century Norton's Ordinall was published in the Theatrum Chemicum Britannicum of Elias Ashmole (Plate 32). This was the work of Robert Vaughan, engraver of similar plates in the works of Henry and Thomas Vaughan; on him, see M. Corbett and M. Morton, eds., Engraving in England in the 16th and 17th Centuries, Part 3: “The Reign of Charles I” (Cambridge University Press, 1964); and the Index of Alan Rudrum, The Works of Thomas Vaughan (Oxford University Press, 1984).

Another reworking of earlier materials (Plate 33) shows Trismegistus in company with Paracelsus, with a central motif inspired by Robert Fludd. This was first brought to notice and reproduced in Allen G. Debus, The Chemical Philosophy (New York: Science History Publications, 1977), val. II, p.515, who pointed out that the portraits of Hermes and Paracelsus derive from those on the title page of Oswald Croll's Basilica Chymica (see our Plate 18), while the central image is a copy of a well-known engraving by Johann Theodor de Bry in the first part of Robert Fludd's Utriusque cosmi historia (Oppenheim, 1617). Hermes says: “Quod est superius, est sicut quod est inferius” (What is above is like that which is below—the opening words of the Emerald Tablet); Paracelsus: “Separate et ad maturitatem perducite ” (Separate and lead it on to ripeness). This montage is the work of Tobias Schitze (Harmonia macrocosmi cum microcosmo, Frankfurt, 1654.) After the middle of the century there do not seem to have been many new works.

It would be fruitful to explore systematically the nonalchemical illustrations of the late Renaissance period, particularly the emblem collections. For instance, George Wither's A Collection of Emblemes, Ancient and Modern (1635) reproduces emblematic works already published by Gabriel Rollhagen in Nucleus emblematum selectissimorum (Utrecht, circa 1611-1613): in the “Choice of Hercules” (Plate 34), an odd allegory, the personage on the left is certainly not Mercury, but the beard, caduceus, and book are the attributes of Trismegistus.

Later on, “trismegistic” illustrations become very scarce, and as we know, the eighteenth century is far less rich in esoteric illustrated documents than the seventeenth. Thus the only eighteenth-century document of which I am aware (though others must exist) is not an illustration on paper, but a painting on wood panel, 63 × 142 ems. (see Plate 35). Anonymous, and probably done around 1740, it comes from the Pharmacy of the Court of Innsbruck (lnnsbrucker Hofapotheke). There are three panels which seem to have made up a kind of triptych, serving as the door to an apothecary's cupboard. Just after World War II it was still in Innsbruck in the house called “Zum Goldenen Dach,” but was purchased shortly after by the Schweizerisches Pharmazie-historisches Museum in Basel, where this triptych is currently exhibited (historical information kindly furnished by Dr. Michael Kessler, Curator of the Museum, during my visit in April 1991 and in a letter of 10 June 1991).

Hermes Trismegistus here carries his traditional attribute, the armillary sphere, in his right hand, and in the left a scroll on which is written the first verse of the Emerald Tablet. The predominant colors are red and blue: red for his robe (the large cape is white) and blue for his cloak, belt, and hat. The two other panels are by the same hand: one represents Hippocrates, the other Aesculapius. Originally, Trismegistus probably stood between the two physicians, but nowadays the three panels are displayed separately, though in the same room.

One of the Egyptianizing masonic rituals of the late eighteenth century (or around 1800) is called “Die Magier von Memphis” (The Magi of Memphis). It has two side-degrees centered around the figure of Hermes Trismegistus. These degrees are called “Sublime Philosopher of Hermes” and “Sublime Magus of Memphis.” In the setting of the lodge, a drawing represents Hermes Trismegistus rising from a grave. He is flanked by two branches of laurel and a Delta hovers above his head. This picture corresponds to the initiation practice in the ritual: after the candidate has entered the lodge, a Brother hidden in a coffin opens the lid from within and rises. This Brother impersonates Hermes Trismegistus and explains that he, Hermes Trismegistus, has emerged from the night of the tomb in order to deliver the candidate from error and confusion. He declares that he has a knowledge of “the most profound mysteries of Nature” and he claims: “This science, I, Hermes, taught the priests and kings of Egypt. They taught each other and achieved the most surprising things, simply by imitating the process of Nature. These secrets were the objects of the Royal Art.” After dwelling on the history of the transmission of that knowledge, he concludes by saying: “Remember me. My true name is Mercurius for the Egyptians, Thoth for the Phoenicians, Hermes Trismegistus for the Greeks, and all over the earth I am Hiram, whose wonderful story has amazed you.”

It is the only masonic ritual I know that identifies Hermes Trismegistus with Hiram, that is with the mythical architect of King Solomon's Temple. In most masonic rituals, Hiram is murdered by two of his companions and then rises from the grave, a scenario enacted by the candidate to the Master degree. The original manuscript of the ritual “The Magus of Memphis” was written in French and preserved at the Freimaurer Museum Library of Bayreuth. It was translated into German in 1928 (by Otto Schaaf, pp.207-245 in Das Freimaurer-Museum: Archiv für freimaurerische Ritualkunde und Geschichtsforschung, vol. IV, Zeulenroda/Leipzig: B. Sporn, 1928, under the title “Zwei Hochgrad-Rituale des 18. Jahrhunderts”). This manuscript is lost without having been published in its original form in French, and was already lost in 1978 (see Karl R. H. Frick, Licht und Finsteris, vol. II, Graz: Akad. Druck- und Verlagsanstalt, 1978, pp.149-157): Fortunately, Otto Schaaf not only published the translation he made into German, but also provided beautiful reproductions of the original nine manuscript illustrations (copies made by Carl Kampe, see 0. Schaaf, op. cit, p.209), one of which is reproduced here (Plate 36). It is the only one featuring Hermes Trismegistus.

Beside other documents of this kind on paper or canvas of which I am not yet aware, there is a drawing (Plate 37) made at the start of the nineteenth century by the theosopher, kabbalist, and alchemist Johann Friedrich von Meyer (on whom see Jacques Fabry, Le theosophe allemand Johann Friedrich von Meyer [1772-1849], Berne: Peter Lang, 1989). Meyer decorated the title page of one of his manuscript works devoted to these fields of esotericism and called Cabala Magica et theosophica with a bearded head that is none other than our Trismegistus.

Finally we note two examples from our own century. First, Plate 38 reproduces Augustus Knapp's painting of Hermes Trismegistusi he is dressed from head to toe in Egyptian fashion, holding a caduceus in one hand and a book in the other, while pinning to the ground with one foot a live, fire-breathing dragon This is one of the most curious figures in the esoteric picture gallery of Manly P. Hall's The Secret Teachings of All Ages: An Encyclopedic Outline of Masonic, Hermetic, Qabbalistic, and Rosicrucian Symbolical Philosophy (Los Angeles: Philosophical Research Society, 1928 and subsequent issues).

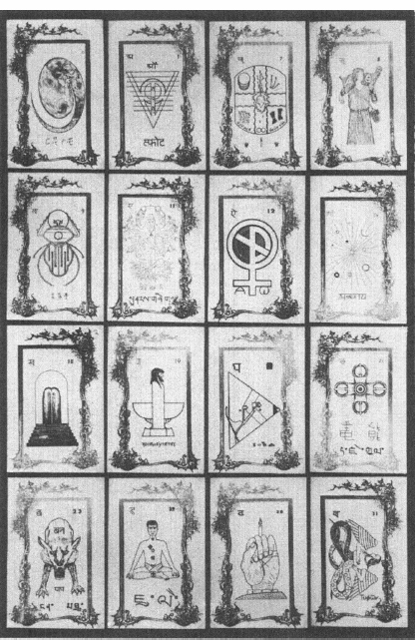

Second (Plate 39), in the most extensive encyclopedia of Tarot, cogently compiled, presented, and commented upon by its author, Stuart R. Kaplan, we find the “Neti Neti Tibetan Tarot.” This deck is dated 1952 and was worked out by the “Christian Community.” Card 19 shows a herma, i.e. a post surmounted with the head of Hermes, in front of a fountain basin. In ancient Greece the so-called hermae were placed as crossroads and entrance ways. Here, the head of the herma is reminiscent of a priest or sage, and a caption beneath the image reads “Trismegistos” in Greek letters. So this picture has a twofold connotation, that of Mercury and that of Hermes Trismegistus. The deck claims to draw on various traditions, not only Egyptian and Greek, but also Chinese, Christian, and—as the title of the deck already warns us—Tibetan.

This collection of images does not pretend to be at all exhaustive. All suggestions for references and new lines of investigation sent to the author in care of Phanes Press will be gratefully acknowledged.

Plates 1 and 2. Two illuminations from a French mansucript entitled Augustinus: Cité de Dieu (fols. 390, 392). End of 13th or beginning of 14th century. The Hague, Museum Meermanno-Westreenianum. Professor Frans A. Janssen kindly called my attention to this document. It is reproduced by courtesy of the Museum.

Plate 3. Norton's Ordinall of Alchymy, 15th century. British Library, Add. Ms. 10,302, fol. 32’. By permission of the British Library.

Plate 4. “Pater Hermes philosophorum.” Watercolor from Miscellanea di Alchimia, 15th century. Florence, Biblioteca Medicea Laurenziana. Kindly communicated to me by Dr. Mirko Sladek.

Plate 5. Illustration from a manuscript of Aurora Consurgens (University Library in Prague, Ms. VI fd 26), second quarter of the 15th century See also Plates 10 and 11.

Plate 6. Maso Finiguerra or Bacchio Baldini, A Florentine Picture Chronicle, being a series of ninety-nine drawings representing scenes and personages of ancient history, sacred and profane. London: Bernard Quaritch, 1898. Middle of the 15th century.

Plate 7. Inlaid floor panel from Siena Cathedral, 1488, by Giovanni di Maestro Stephana.

Plate 8. From a manuscript astrolabe, attributed to the Barnabite Fathers, second half of the 16th century. Milan, Ambrosiana.

Plate 9. Francisco de Holanda, De aetatibus mundi imagines, between 1545 and 1573 (National Library of Madrid, B Artes 14-26). Medallion placed beneath the “Death of Moses,” fol. 26'/LII/45.

Plate 10. De chemia senioris antiquissimi philosophi, libellus, ut brevis, ita artem discentibus, et exercentibus, utilissimus et vere aureus, nunc primum in lucem aeditus. Ab artis fideli filio, dixit Senior Zadith Filius Hamuel. No place, no date; circa 1560. See also Plates 5 and 11.

Plate 11. Extract from an alchemical manuscript containing various watercolors, Nuremberg (Germanisches Nationalmuseum, Ms. 16752), between 1577 and 1583. See also Plates 5 and 10.

Plate 12A and 12B. Painting on a column of the Salone Sistine (Vatican Library). The series of column-paintings in that room is attributed to Luca Horfei (1587) and represents the “inventors” of scripts and alphabets. Here, Mercurius Thoth is the inventor of the Egyptian (“Mercurius Thoyt Aegyptiis sacras litteras conscripsit”). Above Hermes, an Egyptian alphabet. Professor Frans A. Janssen kindly called my attention to this document.

Plate 13. Jean-Jacques Boissard, De divinatione et magicis praestigiis, Oppenheim, no date (circa 1616). Engraving by Johann Theodor de Bry, the illustrator of Robert Fludd and Michael Maier.

Plate 14. Giovambatista Birelli, Opere, vol. I: Nel qual si tratta dell'Alchimia…Con la vita d'Ermete, Florence, 1601, p.SSl. By permission of the British Library.

Plate 15. Andreas Libavius. D.O.M.A. Alchymia Andreae Libavii, recognita, emendata, et aucta (1606). Reproduced as the title page of Libavius's Syntagma Selectorum… (Frankfurt, 1611) and Syntagmatis Arcanorum Chymicorum (Frankfurt, 1613).

Plate 16. Joachim Tancke, Promptuarium Alchemiae, vol. I, Leipzig, 1610. From the Author's Preface.

Plate 17. Michael Maier, Symbola aureae mensae duodecim nationum, Frankfurt, 1617, p.5.

Plate 18. Oswald Croll, Basilica Chymica, Frankfurt, no date (1629, first ed. 1608). The same design was used in the Latin edition, 1611. By permission of Thames & Hudson, Ltd.

Plate 19. Gloria Mundi. Alias, Paradysi Tabula. In Musaeum Hermeticum, Frankfurt, l624. By permission of the Bibliotheca Philosophica Hermetica, Amsterdam. First published in Michael Maier's Symbola (cf. supra, Plate 17).

Plate 20. Paracelsus, Chirurgische Bücher und Schrifen, edited by Johann Huser, Strasburg, 1605; reprint, 1618. By permission of the British Library.

Plate 21. Daniel Stolzius von Stolzenberg, Chymisches Lustgärtlein, Frankfurt, 1624.

Plate 22. Daniel Stolzius von Stolzenberg, Hortulus Hermeticus Flosculis Philosophorum Cupro Incisis Conformatus…, from Manget's Bibliotheca Chemica Curiosa, Geneva, 1702, val. II, p.896. These medallions appeared first in 1618, in the third treatise of Johann Daniel Mylius's Opus medico-chymicum. By permission of Thames & Hudson, Ltd.

Plate 23. Anonymous [=Johann Ambrosius Siebmacher], Hydrolithus Sophicus seu Aquarium Sapientum, in Musaeum Hermeticum, Frankfurt, 1625. By permission of the Bibliotheca Philosophica Hermetica, Amsterdam.

Plate 24. Josephus Quercetanus (alias Joseph Du Chesne), Pharmacopoea restituta, Strasburg, 1625.

Plate 25. Anonymous, Via Veritatis Unicae. Hoc est, elegans, perutile et praetans opusculum, viam Veritatis aperiens. Probably written at the turn of the 15th to 16th century. This illustration accompanies the work in the collection Musaeum Hermeticum, Frankfurt, 1625. By permission of Thames & Hudson, Ltd.

Plate 26. Hadrianusà Mynsicht, Thesaurus et […] Armamentarium Medico-Chymicum. Cui in fine adjunctum est Testamentum Hadrianeum de Aureo Philosophorum Lapide. Lubeck, 1638 (first ed., Hamburg, 1631).

Plate 27. Jean Brouaut, Traité de l'eau de vie, Paris, 1646. By permission of the Bibliotheca Philosophica Hermetica, Amsterdam.

Plate 28. Pharmacopoeia Augustana, Augsburg, 1646. Illustration by Mattheus Gundelach and Wolfgang Kilian. By permission of the British Library.

Plate 29. Josephus Quercetanus (alias Joseph Du Chesne), Recueil des plus curieux et rares secrets…, Paris, 1648. Title page by Michael van Lochem, 1641, of a posthumous collection of Du Chesne's writings.

Plate 30. Josephus Quercetanus (alias Joseph Du Chesne), Quercetanus Redivivus, hoc est Ars Medica Hermetica, Frankfurt, 1648. By permission of the British Library.

Plate 31. Johann Pharamund Rhumelius, Medicina Spagyrica oder Spagyrische Artzneukynst, Frankfurt, 1648. By permission of the British Library.

Plate 32. Elias Ashmole, Theatrum Chemicum Britannicum, London, 1652, p.44. A redrawing of Plate 1 for Ashmole's edition of Norton's Ordinal!. By permission of the British Library.

Plate 33. Tobias Schiitze, Harmonia macrocosmi cum microcosm a, Frankfurt, 1654. Based on Croll (see Plate 17) and on illustrations of the Utriusque cosmi historia (1617) of Robert Fludd.

Plate 34. George Wither, A Collection of Emblemes, Ancient and Modern, London, 1635, Book I, Emblem 22. By permission of the British Library.

Plate 35. Anonymous painting, circa 1740, formerly in the Court Pharmacy of Innsbruck, now in the Schweizerisches Pharmazie-historisches Museum, Basel. By permission of the Museum.

Plate 36. Hermes Trismegistus rising from the grave in order to teach the candidate an initiation. Masonic ritual of “The Magus of Memphis,” end of the eighteenth century or around 1800. From “Zwei Hochgrad-Rituale des 18. Jahrhunderts,” pp.207-245 in Das Freimaurer-Museum: Archivfür freimaurerische Ritualkunde und Geschichtsforschung, vol. IV, Zeulenroda/Leipzig: B. Sporn, 1928 (see p.212). By permission of the Oscar Schlag Library, Zurich.

Plate 37. Johann Friedrich von Meyer, extract from unpublished manuscript Cabala magica et theosophica, circa 1805 (Erlangen, Theologische Fakultät, Institut für Historische Theologie). Document kindly furnished by Jacques Fabry.

Plate 38. Augustus Knapp, color painting of Hermes Trismegistus, from Manly P. Hall, The Secret Teachings of All Ages (Los Angeles: Philosophical Research Society, 1928). By permission of the Philosophical Research Society in Los Angeles.

Plate 39. Card 19, “Trismegistos,” from the Tarot deck “Neti Neti Tibetan Tarot” (Christian Community, 1952). From Stuart R. Kaplan, The Encyclopedia of the Tarot, volume III (Stamford, CT: U.S. Games Systems, 1990), p.392. By permission of U.S. Games Systems, Inc.