CHAPTER 10

The Many-Voiced Socrates: Neoplatonist Sensitivity to Socrates’ Change of Register

Harold Tarrant

Introduction

It is not unnatural for the readers of some Neoplatonic texts to arrive at the conclusion that Neoplatonists had little idea of how one might set about distinguishing Socrates from Plato. Plenty of references to Socrates’ position in the Neoplatonic commentaries leave one asking whether they meant anything different from Plato’s position. One may also suspect that Socrates himself was seen as far inferior to Plato, not least because the two “perfect” dialogues, with which the commentators’ Platonic curriculum finished, employed protagonists whose theological competence was clearly considered superior to that of Socrates. There is, however, another side to the Neoplatonists’ work that needs to be appreciated, and that has more connection with the biographical tradition and with Socrates’ mission as outlined in the Apology than with the formal Platonic curriculum. Though not a divinely inspired author (for he was not an author at all until the final days of his life), Socrates can still be treated as a divinely inspired questioner, committed first to self-examination, and secondly to the examination of others.

It is worth here repeating a passage, already used in Christina Manolea’s chapter, from Hermias’s Commentary on Plato’s Phaedrus (1.5–9), that illustrates what the legend of the beneficent Socrates on his Apollinine mission had come to mean for the school of Syrianus: “Socrates was sent down into generation for the benefit of the human race and of the souls of young persons. As there is much difference between souls in their characters and practices, he benefits each differently, the young in one way, sophists in another, stretching his hands out to all and exhorting them to practice philosophy.” Considering that Neoplatonists now found themselves in an ultimately unsuccessful contest with Christianity, it is likely that such a description is intended to invite comparison between the divine mission of Socrates and that for which Christ himself had been immersed in human life. This is no minor philosopher with whom Hermias begins his commentary; it is the philosophic equivalent of a Messiah. Just as Jesus could not have achieved his fame by asking questions alone, so too this Socrates employs his questions for what is ultimately a hortatory purpose, involving protreptic and conversion, and it is more subtle than that of the Christian Messiah insofar as it takes full account of the differences between those he had to convert. The Phaedrus was a dialogue that made much of the different types of soul, itself suggesting that types of speech needed to be chosen to suit the souls that were addressed (271d, 277b–c), and using many types of speech even in this one conversation with Phaedrus, who might perhaps be regarded as a complex soul himself (cf. 277c2, 230a3–5).

As the brief Platonic Clitophon makes clear, a hortatory or “protreptic” role is not sufficient in itself, and Socrates’ role could be confined neither to questioning nor to exhortation. The recognition that Socrates’ role is one that employs examination did not (as it occasionally does today) lead to the assumption that he had little positive teaching to offer and no doctrines to which he was committed; rather, it led to the primacy of one particular kind of understanding, that of self-knowledge. External examination was intended to lead to internal examination, and the skillful examiner must know how to bring about the desired result. There is much that he does not have to know for this purpose, but that will not make him a skeptic. He must, as the Phaedrus suggests, make the recognition of souls his priority, beginning with the recognition of his own soul. Hermias responds almost with disbelief to Socrates’ apparent disavowal of self-knowledge at 229e5–6, thinking that the phrase “in accordance with the Delphic inscription” must be a qualifying phrase that requires a type of knowledge beyond human achievement. Socrates must know himself in the sense required of us, because knowing ourselves is fundamental to the whole Platonic curriculum, and is taught—taught by Socrates—in the very first work of that curriculum, the Alcibiades.

Olympiodorus, in whose Commentary on the Alcibiades the defining role of self-knowledge in this dialogue is fully discussed, also recognizes within three major sections of the work three separate roles for Socrates as protagonist. In the first major section, to 119a, he employs elenchus in order to demonstrate to Alcibiades his shortcomings; in the second, to 124b, he employs protreptic discourse; and in the remainder he operates as the philosophic midwife, helping Alcibiades toward a correct understanding of the kind of creature that he really is in himself. Elenchus, protreptic, and midwifery all receive extensive discussion in the modern literature on Socrates, so that what Olympiodorus sees as the role of Socrates here may be regarded as genuinely Socratic. It might also be said that he too is recognizing a plurality of Socratic voices and not just one, even though there is once again only one rather complex interlocutor. The range of voices is different in the Alcibiades from that in the Phaedrus, where Hermias can discover in the palinode both poetic diction (174.5–17) and, at least in its final section after the conflicts within the human soul are introduced, myth (230.14–19). The Phaedrus, of course, not only recognizes the existence of inspired speech stemming from the crazed utterances of poets, prophets, purifiers, and lovers (244a–245a) but had actually begun to employ it already in Socrates’ earlier speech (237b–241d), as may be seen in his remarks about the Nymphs possessing him (241e).

One can, at very least, claim that Plato’s Socrates sometimes steps outside his familiar conversational mode and surprises one by embarking upon some nondialectical delivery. One can similarly claim, with some confidence, that Neoplatonist readers were conscious of Socrates’ switches of register, and tended to take special note of the passages concerned. This chapter aims to demonstrate, first, that Neoplatonist commentators were much more sensitive to changes of register than we usually are today, and, second, that the computer is a useful tool for alerting us to the magnitude of these linguistic changes. To put it briefly, while Eudorus of Alexandria is often credited with the affirmation that “Plato is a man of many voices, not of many views,”1 who will speak in different modes in different dialogues, the Neoplatonists recognized that this could also be said of a single character within Plato’s works, his character Socrates.

The Background

A group of researchers based in Australia have recently been analyzing Plato’s most basic vocabulary. Our analysis deals only with words likely to be among the three hundred commonest in most subsets of Plato’s works, and aims to use the majority of words for which any of Plato’s more conversational dialogues would be expected to find some use,2 regardless of the nature of their subject matter or of their choice of narrative or dramatic presentation.3 Such words were designated “function words.” In all, there were ninety-seven of these that regularly featured in our analyses. It is obvious that vocabulary is a familiar and important component of style, and it has often been a focus of stylistic studies on Plato, as a glance at Brandwood (1990) will show. The major difference with our methods is that they study a large part of the recurrent vocabulary of a body of texts, using multivariate analysis rather than selected items or groups in which individual scholars may have developed a particular interest. It is possible to identify the exact words that are contributing to striking results, and reflection upon the reasons for an increased or decreased use of these words affords better hope of understanding results than would be the case when analyzing letter patterns or clausulae, for instance.4

We prepared noninflected texts, so that the definite article, demonstratives, declining pronouns, adjectives, nouns, and verbs had a single form only. Dialogues were routinely divided into two-thousand-word blocks, with any remainder added to the last block, giving it a maximum of 3,999 words. For each vocabulary item its percentage of total vocabulary within each block was calculated. Factor analysis and cluster analysis was then applied to all ninety-seven common words, to ninety-six words (without the article), to forty-seven words that Plato might have used more sparingly than comparable authors, and to twenty-five words for which Plato seems to have a liking.

It soon became obvious that the computer was inclined to group together works that did indeed have something (other than subject matter) in common, with different tests on different groups of works highlighting different common features. Some tests seemed to separate genuine works from the spuria, such as Sisyphus and Axiochus, quite well, others achieved a good separation between early Plato and Xenophon. The forty-seven-word test was able to point to similarities between the Alcibiades dialogues, Hipparchus, the first half of the Theages, and the Minos,5 and further refinement found nine words that were particularly favored by this group relative to unquestionably genuine dialogues. Some tests seemed to offer hints at the chronology of Plato’s works, though without the radical separation of “late” from “early/middle” that hiatus rates and clausulae preference seemed to offer, since Plato’s working vocabulary developed seamlessly, without the obvious shift that conscious stylistic decisions produce. Several tests that concentrated on early/middle dialogues were able to give reasonable separation between dialogues in dramatic and in narrative form, but with the striking exception that all blocks of the Theaetetus would be placed by twenty-five-word tests wholly within the narrative group.6 Finally, it seemed to make a huge difference whether or not what was written was intended as myth or other inspired diction.7

I begin with an illustration of the differences that could be recognized. If one tested a group of early Platonic dialogues, including the Apology, Charmides, Crito, Euthydemus, Euthyphro, Laches, Lysis, Meno, and Republic I, using factor analysis based on ninety-six function words (leaving the article aside), a difference was regularly observed on the second factor between the blocks of dialogues in dramatic form, which appear on or above the zero line, and those of narrated dialogues, which appear on or below it. This was thought rather surprising given that certain words had been excluded from the tests precisely because of their being required much more in one group than the other. If one then adds the four dialogues of Tetralogy IV, the two blocks of Alcibiades II and the Hipparchus (both dramatic dialogues) are placed in territory otherwise occupied by narrative dialogues. Furthermore, while the Alcibiades I followed expectation as regards its place on factor 2, all its five blocks were placed far to the right (on factor 1), in an area that otherwise contained a single stray block of the Meno that overlapped with the mathematical language of the examination of the slave. One recognizes that an artist like Plato will have motives for varying his style in a particular part of a dialogue, but one does not expect him to write virtually the whole of a ten-thousand-word dialogue in a different style without good reason.

The aberrant features of the Alcibiades I did not prove its spuriousness, but pointed to differences that might need explaining by those who regard it as a genuine dialogue of the Socratic type. Much the same applied to the aberrant tendency of the Hipparchus and Alcibiades II to be placed by our analysis among the dialogues in narrative form. Interestingly, some later authors had their suspicions about the authenticity of these two,8 though none seem to have doubted the Alcibiades I. In fact, from the time of Albinus (Prol. 5), most appear to have afforded this dialogue a unique introductory role that might explain its distinct stylistic features. One may point to its special pedagogic concerns, which make this “Socrates” adopt a rather didactic approach and present all arguments in a rather simple fashion for a youth who appears to have taken little interest in philosophy previously. Reading these dialogues in their own language, and potentially with a wider knowledge of Socratic literature than we can derive from what survives today, late antique Platonists could sense that different dialogues of Tetralogy IV displayed different aberrant features, and could explain these features in different ways.

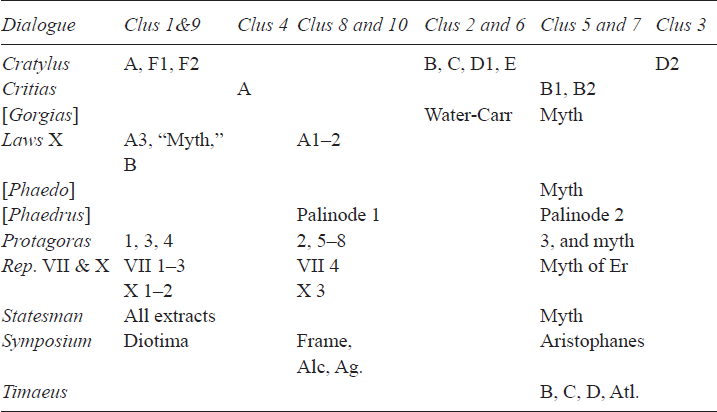

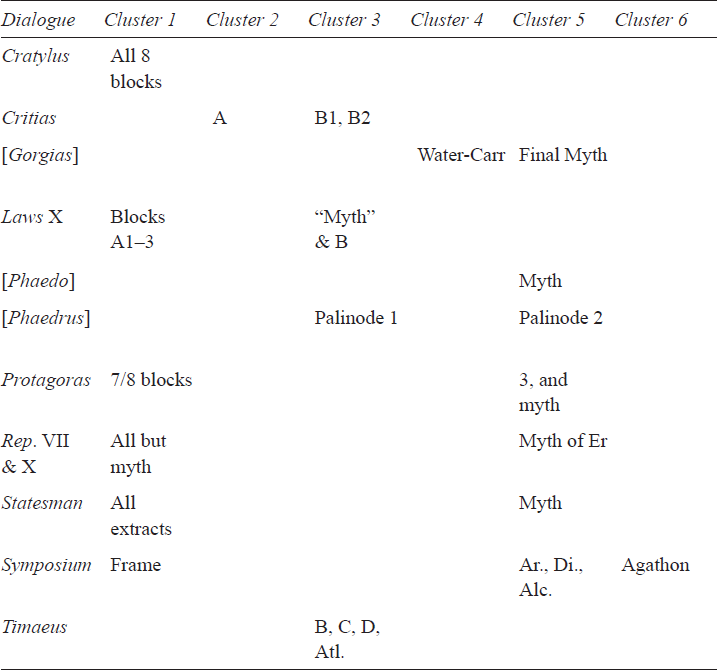

The Neoplatonist Response to Myth

The most striking difference to be found in many dialogues through our analyses was the difference between myth (and related revelatory diction) and ordinary conversational language, whether dialogic or monologic. These differences must have had the effect of alerting the reader or listener to something special about the myth-like passages. The differences were easily captured in cluster analyses, especially when the amount of myth-like and nonmyth material was approximately equal. Cluster analysis, often represented by dendrograms that look rather like a family or evolutionary tree, produces family clusters of the analyzed materials. For us the materials were sets of percentages illustrating the relative frequencies of vocabulary items for various discrete blocks of text. Each of the families is linked at a notional level of similarity and is calculated according to a certain method. We have provided several examples of dendrograms capturing the differences of myth-like diction elsewhere,9 so it will suffice here to illustrate the kind of results obtained by tabulating the contents of clusters. Here is an example that employs McQuitty’s method of analysis,10 nicely dividing myth and its allies (in clusters 3 and 5) from nonmyth (in cluster 1) with three seemingly anomalous blocks being allotted clusters of their own (Table 3).11

The two “myth” families seem to be divided roughly into what might be seen as late12 and early/middle material, though the Statesman myth is placed in the earlier group and the palinode of the Phaedrus is divided between the two. While it may surprise some that the Diotima episode and speech of Alcibiades are included in a myth group, both involve storytelling, and a certain revelatory element. These two “myth” families exhibit a greater degree of similarity with one another than with cluster 1, which contains most nonmyth material.13

If we were writing principally about Plato, then it would be normal to analyze the same data, and other data with a modified list of dialogues, in different ways. One such way is recorded in the appendix to this chapter. Many of the myths included in this analysis, however, have not even been narrated by Plato’s “Socrates,” who, together with Plato’s later interpreters, is the principal focus of this volume. Socrates narrates the myths of the Gorgias, Phaedo, Phaedrus, and Republic X, and at least retails Diotima’s narration of the myth of Poros and Penia at Symposium 203b1–204a7. Computational stylistics shows how all these myths stand out from surrounding material,14 even the myth of Poros and Penia.15 The presence of the myth of Er in cluster 5 of the above analysis, and of everything else from Republic VII and X in cluster 1, is not an isolated occurrence. Given that any Platonic speaker speaks differently when becoming the narrator of a myth, the important question is how far later Platonists were aware of Socrates switching voices as he moves from his dialectical register into that of the myth narrator. It will be my contention here that the Neoplatonists were very well aware that in many dialogues Plato, and Plato’s “Socrates,” tended to slip into a different voice or “register” in order to communicate a myth or similar nonstandard material, and that this register invited a different, and indeed a heightened, response from the reader. Hence no dialogue that contained a major myth narrated by the lead character is absent from the late Neoplatonist curriculum.16 The Gorgias, Phaedo, Statesman, Phaedrus, Symposium, Republic, and Timaeus are all included, and partial commentaries on all but the Statesman and Symposium are extant. We shall examine myth’s importance more fully later.

Table 3. Cluster analysis of selected mythical and nonmyth passages

Note: Only myths are included from the Gorgias, Phaedo, and Phaedrus, while materials from the Statesman, Symposium, and Timaeus were selected as follows: Statesman 291a–297c, 297d–303d, 303d–end; Symposium from 189c2, frame being material outside the major speeches; Timaeus Atl. = 22b6–25d6, B = 38b6–46c6, C = 58c4–65b7, D = 79a5–86a8. The “myth” in Laws X = 903b4–905d1, A1–3 are all that precedes it, and B is all that follows it.

The Status of the Palinode

The statistical ambiguity of the early part of Socrates’ long palinode speech in the Phaedrus (243e9–257a2), seen in the fact that its first two-thousand-word block was placed in cluster 3 while the remainder of it was placed in cluster 5, should raise questions in our minds about where the myth proper begins. The earlier pages contain much material that would normally be thought to prefigure the myth proper, and we have already observed that the later pages are, in a sense, “deeper” myth.17 Now Syrianus’s pupil Hermias,18 our sole commentator on the Phaedrus, often (thirty-four times) uses the term “palinode” to describe the speech as a whole. So he thinks of it primarily as a kind of poetic construction with a debt to Stesichorus, and his awareness of the poetic nature of the wider passage becomes clear in his comments on 257a5 (206.18–26 Couvreur = 246.2–10), where he asks why Socrates had thought poetic language necessary, giving examples that show he sees that Plato is competing with the poets, a fact made obvious at 247c4. Only at 193.7–12 (= 230.14–19) does Hermias use “myth” in relation to this speech, and this is a direct response to Plato’s use of that term at 253d. Phaedrus 253d in fact suggests that the start of the myth was 246a, not the beginning of the palinode at 243e, but Hermias for his part thinks it significant that the actual term is not used at all until this point, when the vicious nature of the bad horse is introduced in order to explain the behavior of the human soul.

With this in mind I divided the palinode at 246a and 253d, giving three sections named PalinA, PalinB, and PalinC. The “Lysias” speech was named PhdrS1, and Socrates nymph-inspired response PhdrS2. What preceded PhdrS1 was named Phdr.A; what came after that and before PhdrS2 became Phdr.B; the passage after that and before the palinode became Phdr.C; and what followed the palinode became Phdr.D1–3. The Phaedrus was analyzed alongside the Republic IV, VII, and X, Phaedo, Symposium, and Statesman. Blocks that used the language of myth (or similar) fairly consistently, including Statesman block 3 as well as Aristophanes’ speech in the Symposium and the myth of Er (given separate files), tended to stand out in all analyses; and blocks that included some such language—for example Phaedo blocks 5, 10, and 11 (79b–84d, 106b–111e, 111e–118a)—often did so too.

However, one needed to know not just what was in the voice of myth but what was most extreme in this regard. Principal component analysis employing eighty-seven function words was therefore employed to try to place the blocks in an order. In relation to the first principal component, myth blocks achieved scores in the positive range, but they were not entirely alone, since blocks from the Statesman also did so. These, however, except for Statesman 3, a block that incorporates the myth, received negative scores on the second principal component. So mythical language consistently seemed to be confined to those blocks that were placed in the positive range on both first and second principal components. The following blocks fell into that category, and have been listed according to the sum of the values of first and second principal component: PalinC (11.687), Statesman 3 (10.279), myth of Er (9.176), PalinB (9.117), PhdrS2 (5.551), PalinA (5.102), Symp.–Ar. (3.682), Symp.–Eryx. (2.947), Phaedo 11 (2.322), Rep. VII.4 (1.487), and Symp.–Diot. (1.225). Because of minor variations in Plato’s styles over time, this is only a very general indication of the relativities between dialogues, but other results also confirmed that PalinC was more obviously myth-like in its language than PalinB, while doubt remained over whether PalinA was myth-like at all, since it was placed close to Socrates’ earlier speech, advising that the lover should not be gratified. That had clearly not been telling a myth, even though participants agreed that the speech was inspired (238d1, 241e1–5). All these Socratic monologues differed greatly from the earlier speech of Lysias (principal component scores: –7.769 and 4.623), which resembled nothing more than the speech of Phaedrus in Symposium (–5.227 and 4.359).

According to my interpretation of the results, the palinode speech was intended to sound inspired throughout, beginning with the discussion of four kinds of inspired madness: prophetic, cathartic, muse-induced, and erotic (244a5–245c1; cf. 265b). After the brief discussion of the soul’s immortality (245c2–246a2), we meet the unmarked beginning of the myth (according to Hermias), that is, the start of PalinB. If PalinA has employed a kind of cathartic-inspired speech, going to the heart of the misconceptions that had made it seem desirable to avoid gratifying the lover,19 PalinB makes it clear that Socrates is now in direct competition with the poets (247c3–4). Competing with the poets might perhaps be thought to involve myth, owing to the mythical subject matter of so much of traditional poetry, yet poetry does not have to be mythical. Though the palinode had been in competition with Stesichorus from the beginning, PalinA was nevertheless offering a classification of the better kind of madness, on the basis of which love is rehabilitated, followed by a proof of the immortality of the soul. This is philosophy dressed in a kind of poetic prose. But PalinB engages in a contest with the poets in a manner more akin to the Timaeus’s engagement with Hesiod.20 In so doing it resorts to the use of complex imagery as well as to poetic language, and the repetition of resemblance terminology at 246a5–6 (eoiken, eoiketô) suggests that we have another attempt to create an eikôs mythos (as Timaeus 29d2 would have it). While I do not wish to make much of this much-discussed phrase, I do want to draw attention to my group’s recent research that demonstrates how the language associated with Plato’s myths is not present, or at least not fully present, when Timaeus is discussing the enduring principles of the universe:21 that is, it is not present prior to the description of the creation of time (37c–38b), according to the general principle that precise explanation cannot be given in the case of generated images in the same way as when discussing eternal paradigms. Myth deals with what is in time rather than what is extratemporal.

Now Hermias (193.9–14 = 230.16–21) seems to come close to such an explanation of why the account has explicitly become a mythos at 253c. Let us look more closely at what he says: “It is because from this point the soul is in the body as if in an image; for the whole body that appears about us and is wrapped around us and indeed the whole phenomenal world is like a myth. So it is with good reason that when he wants to speak about the relation of the soul to body he calls [his words] a myth, whereas in what preceded he did not use this word, since the soul was on high with the gods and in possession of different horses.”22 It is not, for Hermias, a question of myth being unable to explain matters divine, but rather his recognition that Plato generally uses it to present us with a picture of what goes on unseen in this world of ours, especially in our souls while they are subject to conflicting forces. But Hermias may also have been conscious that the language, though poetic throughout, was getting increasingly like that of Platonic myth (as in the myth of Er, for instance). At any rate there is a recognition that the application of the chariot image from 253c7 onward to the individual soul’s worldly experiences is more myth-like than when it had merely explained the disembodied ascent to the heavens of divine and human souls alike.23

The status of the Phaedrus’s palinode is further brought into question by the fact that the Neoplatonists knew other myths about the travels of the disembodied soul as nekuiai, but not this passage.24 The myths of the Gorgias, Phaedo, and Republic X constitute the group of myths routinely known as nekuiai by Proclus (in Remp. 1.168.11–23), Damascius (in Phd. 1.471, 2.85), Olympiodorus (in Grg. 46.8–9, in Meteor. 144.13–145.5), and Elias (in Isag. 33.11–18). Though the palinode talks of the experiences of the disembodied soul, and though Hermias might be reluctantly conceding that this passage is already myth (though not marked as such), no part of the palinode is included among nekuiai, and the first block of the palinode is placed in the same cluster as the myths of judgment in neither Table 3 nor Table 8.25 It could be claimed that the palinode’s failure to include any equivalent to Hades sets it apart, but there is a chance that the later Platonists noticed more than just a connection of subject matter behind the myths of judgment. For on the criteria employed the three myths seem to share a style not consistently used in the palinode.

Inspired Texts, Curriculum, and Special Attention

I think we have here further evidence that the Platonist commentators were listening not only to what Plato’s “Socrates” said but also to how he was saying it, picking up changes of register as he moved into poetic or mythic mode, or into some other kind of inspired speech. Inspired speech of course meant important speech for the Neoplatonists. That in turn meant speech that had to be taken into account in their teaching. Thus dialogues including inspired speech were the most likely to appear in their curriculum. Among Proclus’s works the Platonic Theology demonstrates the importance of myths by using them in particular as a source for theology, while in his Commentary on the Cratylus Proclus recognizes the revelatory nature of etymological material concerning the gods of myth, affording it extensive discussion. Furthermore, he is unconcerned by the status of Timaeus’s cosmology as an eikôs mythos (in Tim. 1.353), as this would, for him, make it more important than a dialectical treatment of physics.26 He sees the Timaeus as a whole (in Tim. 1.7) as blending Socratic with Pythagorean character, with the additional Pythagorean element giving:

1. An intuitive and inspirational lift;

2. links with the intelligible;

3. mathematical content;

4. symbolic and mystical hinting;

5. a more didactic approach.

Hence it is clear that he appreciates that the Timaeus speaks rather differently from most Platonic works, and apparently not simply through Timaeus’s words only, since much of this would apply to Critias’s foreshadowing of the Atlantis story. Proclus’s treatment of the Atlantis myth shows a commitment to the view that myth by definition has a deeper meaning,27 though in Plato it is constructed to make even the surface meaning plausible.28 The deeper (symbolic) meaning will necessitate much close interpretation.

Olympiodorus also recognizes myth as special. He has to deal with two myths in the Gorgias, the brief Water-Carriers myth and its interpretation, and the final myth of judgment. He regards the Water-Carriers material not only as myth but also as Pythagorean (in Grg. 29.3–4, 30.1, 3, 5), thus continuing to make this connection as Proclus had done. He allots to this myth, and to the multi-jar image that follows, considerable importance relative to the other proofs that he sees being employed against Calliclean hedonism.29 He allots lectures 46 to 49, 8 percent of his commentary, to the final myth, 523a–524d, which is just 2 percent of the Gorgias. He affords this myth the task of revealing the paradigm relevant to constitutional happiness (46.7). Somewhat unexpectedly, he is prepared to define myth as “a false statement mirroring the truth” (46.3), but there is certainly no intention of belittling its role. Rather the commitment is to requiring a deeper interpretation for any Platonic myth than may, at first sight, seem necessary, since Plato’s myths, even when taken literally, are not harmful like those of the poets (46.4–5). All myth requires such interpretation, and is constructed so as to conceal the message from inappropriate readers (46.5). But Plato still apparently includes some literal truth (49.1).

The anonymous Prolegomena confirm that Plato was thought to speak differently, both within the Gorgias in the myth and what follows it, and within “theological dialogues” more widely (which must of course include Timaeus). In a passage already employed by Danielle Layne in Chapter 5 (17.2–18), the author contrasts the use of styles that he labels “rich” and “plain” (ἁδρός, ἰσχνός), relating them to the solemnity or everyday nature of their subject matter. This literary terminology does not perfectly capture the phenomenon that we have noted, but it does come close.

The “Euthyphro” Voice in the Cratylus

Mention of the Water-Carriers myth may remind one that this and the following multi-jar image gave an ambiguous response to the tests designed to group myths and nonmyths together (Table 3 and the chapter appendix).30 When tested without the article it seemed almost without parallel, but when the article was included, even though it occupied a separate cluster (6) it was fairly close to the central blocks of the Cratylus (B, C, D1, E),31 and more distantly related to the myths of clusters 5 and 7 as well as to Cratylus D2. There is indeed a link between the Water-Carriers and this part of the Cratylus, one that concerns notionally inspired hermeneutics rather than myth. Socrates is ironically pretending to be inspired by the religious expert Euthyphro from Crat. 396a to 427d, as a result of which Cratylus is able to observe at 428c that he has been intelligently (kata noun)32 oracle chanting (chrêsmôidein),33 “whether you have become inspired from Euthyphro, or whether we have overlooked some other Muse within you.” This and other snippets34 make it clear that Socrates is supposed to be adopting some kind of inspired tone of voice. Hence sections C, D1, and D2 of the work, with or without sections B and E, are liable to be placed in any of our analyses at a distance from sections A, F1, and F2.35 This has the effect of making these central blocks respond somewhat like a late dialogue to a variety of stylistic tests. Consider the results of a cluster analysis in which several dialogues (early, middle, and late) have been compared.36 One of three major clusters groups together the blocks listed in Table 4.

These central Cratylus blocks, together with a single stray block of Gorgias (no doubt somewhat influenced by rhetorical style), have been grouped together most closely with the Statesman (from 264a3), and somewhat more remotely with Statesman block 1 (to 264a3) and the first three blocks of the Sophist. By contrast, the four outside blocks of the Cratylus (1, 2, 8, and 9, to 396c6, and from 428c1) have been grouped closely with six blocks of the Gorgias, four of the Meno,37 three (out of eleven) of the Phaedo, three (out of four) of Republic I and one of X, with three early blocks of the Theaetetus. This material has a distinct early-to-middle feel about it, though some may be mildly surprised at the inclusion of three blocks from the Theaetetus and Republic X.38 The remaining block (4, 403b1–409c6) appears in a different part of the analysis where Republic predominates. The main message to be derived from the analysis, however, is that the outer blocks of the Cratylus are very different in an important matter of style (its mix of recurrent vocabulary) from the central blocks, in which the voice of “Euthyphro” is heard. This might be partly explained in terms of chronology, since the dialogue has apparently been revised,39 and the hiatus rate drops noticeably in blocks 3–7,40 where one might have expected the technical nature of the material to lead to an increase. I suspect, however, that it has more to do with Socrates’ adoption here of the voice of “Euthyphro,” something that tends to make it resemble later material;41 for the tendency of the mythical register is also to make material seem later. 42

Table 4. Content of central cluster of multi-dialogue analysis

Dialogue |

Blocks concerned |

Parameters |

Gorgias |

Block 1 only |

Up to 453b1 |

Cratylus |

Blocks 3, 5, 6, 7 |

396c6–403b1, 409c6–428c1 |

Sophist |

Blocks 1–3 |

Up to 236e3 |

Statesman |

All blocks |

Whole dialogue |

The issue for the Neoplatonists was to determine which passages they should give particular prominence to. The fact that Socrates keeps reminding us that he owes his eloquence to outside inspiration during this part of the Cratylus was already an indication for them that closer and deeper interpretation was required at this point. Our sole extant commentary is that of Proclus, mediated by some note taker, and quite possibly abridged. For convenience we shall assume that these are Proclus’s own views. Here is what is said on 396d: “Now seeing many men like Euthyphro who hold bestial thoughts about gods, Socrates himself descends from the scientific level of activity to an inferior one, but elevates those restricted by impressionistic thought to the middle state of conception about gods. He therefore blames Euthyphro (396d) for this, not because the latter is a leader of this [type of] understanding, but because he rouses Socrates to the pursuit of truth by his impressionistic absurdities” (in Crat. 116, tr. Duvick). It seems that Proclus does have some awareness of Socrates’ switch to a different discourse at this point. That discourse is for him “doxastic” rather than “phantastic” or “epistemonic,” hence it is (a) unusual, and (b) operating at the level usually associated with poetic or religious inspiration—divine dispensation without understanding (theiai moirai aneu nou, Meno 99c–100b, Ion 542a). Socrates is seen as working toward theology through the doxastic world of the lawgiver of names, not in his normal epistemonic fashion. None of this causes Proclus to deal any less earnestly with the etymologies of the gods that follow, but he does seem very conscious that Socrates does not speak in his normal way.

Up to this point we have seen that Socrates’ speech changes in myths, and that Platonists respond to this by paying special attention and offering deeper interpretation. Hermias may in fact be rather more aware of the extent to which the palinode of the Phaedrus should be regarded as myth. Again, we have seen some attention paid by Proclus to a voice shift in the Cratylus, at a point where modern readers would be more inclined to think of Socrates’ reference to Euthyphro as simply ironic.43 Finally, I should like to ask whether there is any similar shift in the Alcibiades I, and what is noticed.

Protreptic in the First Alcibiades?

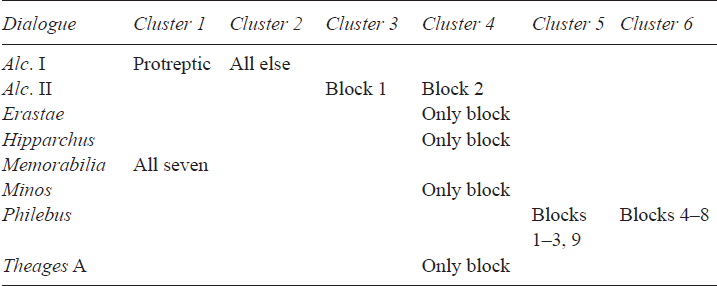

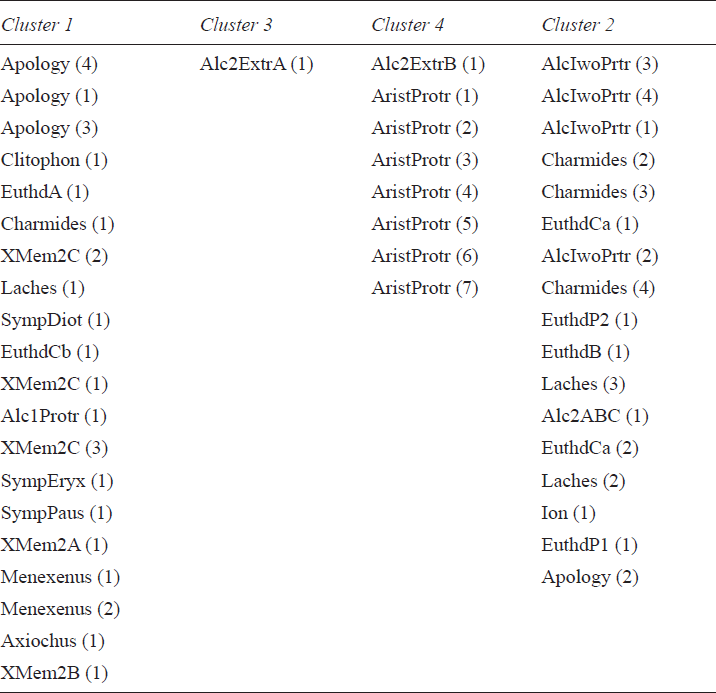

It is natural to think of the structure of the Alcibiades as pedimental (A1, B, A2).44 Modern commentators might see Socrates’ monologue (121a–124b) as the central section. Olympiodorus, however, labels his central section as protreptic, and he regards it as running from 119a to 124b. Stylometry suggests that this is right. There is certainly a rather different voice that is employed hereabouts, and I was not easily able to separate off 119a–121a stylistically. Terry Roberts and I have published a scattergram, based on factor analysis, that charts various parts of the Alcibiades I against a great deal of other material from early or middle Plato, the dubia and spuria, and Xenophon.45 In that diagram Alc1Extr is the monologue only, and Alc1Protr the entire protreptic passage as envisaged by Olympiodorus, and they are placed very close together. Since they contain overlapping material, this was always likely. Analysis after analysis indicates that a substantial central section of this work is in a different register from the surrounding passages in which Socrates engages Alcibiades in argument. This section is also closer to Xenophon than to other blocks of the Alcibiades I. The proximity to Xenophon is also clear in the cluster analysis given in Table 5, which compares doubtful works, Memorablia I & IV, and Philebus.46

Clusters 5 and 6 are close, as are clusters 3 and 4, which are more distantly related to cluster 2; cluster 1 is joined at some distance to clusters 2, 3, and 4, and only after this is all the Socratic material joined to the Philebus clusters.47 This confirms the stylistic remoteness of the protreptic passage from the rest of the Alcibiades I, but what it cannot do is to confirm that it is written in a protreptic voice—except to the degree that Xenophon’s Memorabilia place great emphasis on Socrates’ ability to encourage young persons toward leading an honest and thoughtful life. Book II exhibits this tendency particularly well, and nowhere more so than in the myth of the Choice of Heracles and the preceding attempt to reform Aristippus. What seemed to be required was an analysis that included with selected Platonic texts Memorabilia book II, divided into the discussion preceding the Choice of Heracles, the Choice of Heracles itself, and everything following it (XMem2A, XMem2B, XMem2C).

Table 5. Cluster analysis of Alcibiades I with dubia, Philebus, and Xenophon

Since many Platonic texts have been claimed to have a protreptic element or a protreptic purpose, turning the listener to some kind of philosophy or to virtuous behavior, it would be important to include the two texts that employed the adjective “protreptic,” Clitophon and Euthydemus, with the latter divided in a way that isolated the two passages that seem to illustrate Socrates’ idea of protreptic (Eu-thdP1, EuthdP2),48 separating them from what precedes the first, what intervenes between the two, and what follows the second, with a separate file also for the final discussion with Crito, which would seem to be as much a protreptic to philosophy as anything else in the work (EuthdA, EuthdB, EuthCa, EuthdCb). Most speeches in the Symposium could be argued to be protreptic in nature, and those of Pausanias, Eryximachus, and Diotima-Socrates were selected. The Menexenus also seemed to offer an example of hortatory rhetoric close to protreptic, and the Alcibiades II seemed to offer another case of Socrates more obviously taking an advisory role concerning Alcibiades’ future, with two speeches of perhaps an “apotreptic” role rather than a protreptic one (141c9–142e5, 148b9–150b3), so these were taken separately, and other matter included separately. There was no presumption that the Alcibiades II would behave like a genuine Platonic dialogue, and this applied still more to the Axiochus, which is “protreptic” to the extent that it encourages one to be philosophical in the face of death. To these were added the Apology, Charmides, Ion, and Laches, as regular examples of Plato giving Socrates his say.

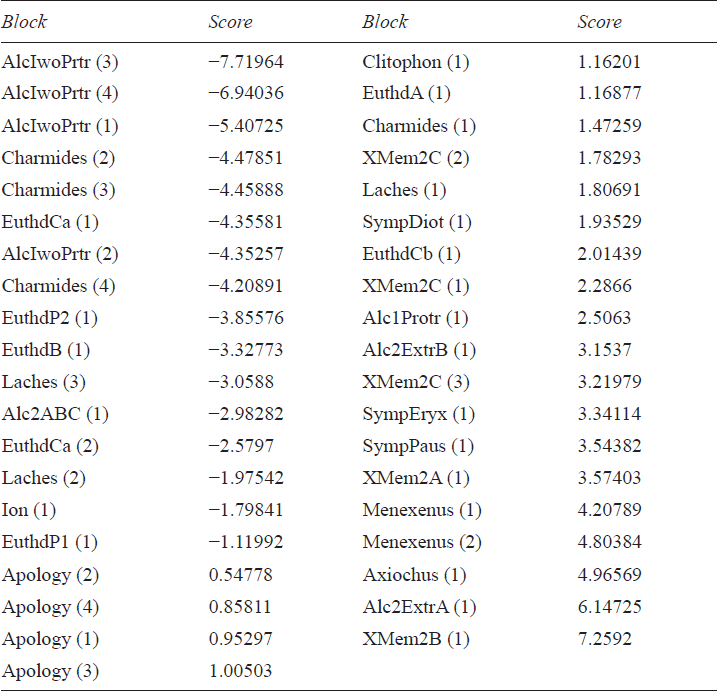

Cluster analysis seemed to divide these materials quite sharply between plausibly protreptic passages and others, but with some surprises. In particular, those passages of the Euthydemus where Socrates demonstrates his kind of protreptic (278d, 282d) were not placed among what seemed to be protreptic passages, but the opening of the dialogue, and the closing discussion with Crito (appropriately) was. So too were the opening blocks of both the Laches and the Charmides, in both of which (one might argue) philosophic engagement is encouraged. When principal component analysis was used to separate the two major areas of difference, the first principal component confirmed that the “protreptic” passage in the Alcibiades I was indeed sharply distinguished from the other blocks, and that it largely kept the company of blocks that could plausibly be described as protreptic (Table 6).

It was tempting to see all results well into the positive register as potentially examples of protreptic, and it was noticeable that four of these blocks (XMem2B, SympDiot, and both Menexenus blocks) share with the protreptic of the Alcibiades I the use of female voices. Exactly what qualifies as protreptic is not a matter of agreement among scholars,49 and is not likely to be settled easily by the kind of computer tests that we have been applying. As we struggle to determine whether or not Olympiodorus is right to choose the term “protreptic” to characterize the central section of the Alcibiades, we find only one paradigmatic text against which philosophic protreptic may be measured—Aristotle’s highly influential Protrepticus. For sure, this was the work of a different author, with a style sufficiently distinctive for scholars to have spotted most of the fragments within Iamblichus’s own Protrepticus (VI–XII),50 so that one does not expect it to look very close to Platonic protreptic; but it was nevertheless worth discovering where cluster analysis placed these Iamblichan chapters. The result is given in Table 7.

Table 6. First principal component scores on “protreptic” test

It is important to report that cluster 1 is first joined to cluster 3 at a similarity level of −4.45, then to cluster 4 at a similarity level of –58.80, and only then are all three of these clusters joined to the non-protreptic cluster 2 at a similarity level of–101.86. In other words, the material in Iamblichus’s Protrepticus and from Aristotle’s Protrepticus is considerably closer to the Platonic “protreptic” material than to material that does not have this function. Furthermore, Aristotle’s Protrepticus is actually in the same cluster as a seemingly protreptic passage of the Alcibiades II. While it is in any case evident that Olympiodorus has correctly picked a substantial shift from Socrates’ normal voice, recognizing it as in some sense “other,” it also seems that the label “protreptic” which he gives to this voice is not without justification.

Table 7. Cluster analysis including Aristotle’s Protrepticus (Ward’s method, Euclidean distance, and standardized data)

Conclusion

It is true that the Neoplatonists did not necessarily appreciate what was authentic and what was not, and also that they were capable of reading some quite unexpected doctrine into the words of Socrates, as well as inclined to miss—perhaps through excessive reverence—many of the instances of irony (of whatever kind) that we should postulate. They can, however, help us to appreciate the detail of Platonic texts regarding register changes within any given dialogue—even where Plato’s Socrates remains the main speaker. The computer helps to drive home to us today the way that Plato’s basic language changes along with changes of register, usually underscored by Socrates’ adoption of a myth-telling, poetic, priestly, or even female persona. One may presume that Neoplatonist familiarity with the nuances of Greek and their working within a culture of reading Plato did enable them to pick up, and respond to, changes of register in cases where the main speaker remains unchanged.

As far as Socrates is concerned, therefore, the Neoplatonists are not interested in distinguishing a true Socrates from a Platonic spokesman, nor even an elenctic Socrates from a dialectical one.51 What they are interested in taking note of is where Socrates steps out of his routine role as a questioner (with a keen sense of the answers that he requires) and adopts some other voice: a new persona (as a student of drama would put it), or a new register (as a linguist would put it). For them the nonstandard Socrates was the one to take special note of, and usually a sign of inspired speech—and hence a further step toward the divine revelation for which the Neoplatonists were seeking.

Appendix: Cluster Analysis of Myth and Other Files, F97 (Definite Article Included)

Because the definite article tends to constitute between 7 percent and 14 percent of the total number of words in a block of Platonic text, its power to skew results tends to be excessive. Hence Table 3 above is an analysis of ninety-six of the commonest permitted function words excluding the article. However, an increase in the rate of the article is normally an important feature of myths in Plato, so here I offer a table of results for an otherwise equivalent analysis that includes the article. Ten clusters were requested, but closely related clusters have been combined in Table 8.

In brief, clusters 5 and 7 have included only blocks that seem to contain myths, while the ambiguous position of the first part of the palinode of the Phaedrus is reflected in its removal to cluster 8. Clusters 2, 6, and 8 (containing the Water-Carriers myth and the central blocks of the Cratylus) are loosely connected with the myth clusters. On this test the alleged “myth” of Laws X does not respond as expected of a myth.

Table 8. Cluster analysis of selected mythical and nonmyth passages: myth, etc., files, F97 (McQuitty’s method, Euclidean distance squared, raw data)