Chapter 3

Understanding Psychopathology and Disruptive Behavior

What Is a Psychological Disorder?

Throughout history humans have attempted to understand the causes of behaviors that seem to be unusual or dysfunctional. Humans seem to have both an ability to allow a wide variety of responses to any one event (without assuming something is “wrong”) and to identify when behavior becomes worrisome. We give others space to behave in normal, predictable ways or even in odd and unpredictable ways. But there is also a limit, a line that people or societies may draw to differentiate the range of normal behavior from behavior that is substantially abnormal.

Greek and Roman medicine sought to understand human behavior from a very biological perspective. The Greek scientist and physician Hippocrates (often considered the founder of Western medicine, and the namesake for the Hippocratic Oath) believed that human health was importantly related to the balance of four “humors” in the body: phlegm, yellow bile, black bile, and blood. Imbalances in these liquids would affect not only people's physical health, but also their behavior. Hippocrates also worked to begin a system to classify emotional disorders, using terms still popular today, including mania, melancholia, and paranoia. There is a long and evolving tradition for natural science in the investigation of human behavior.

There is also a long history of looking to the supernatural for causal explanations of unusual behavior. The ancient Persians believed that many of the stresses of life could be tied to the actions of demons and demonism including two especially important gods, Angro-Mainyus (the malicious actor) and Ahura-Mazda (the benevolent actor). Exceedingly unusual behaviors could be seen as the direct influence of malevolent demons and intervention or treatment could be sought by appeal to Ahura-Mazda. This demonism, however, is not confined to ancient Persia, but also is a part of many more modern religions. Jewish, Christian, and Islamic lore or belief continues to hold that demons exist and exert influence over human life—or even occasionally “possess” certain humans. Although no evidence exists to disconfirm existence of these supernatural beings, dealing with them will remain a clerical or spiritual duty. Sciences such as psychology must attempt to study observable causes of mental distress of dysfunctional behavior.

The fifth edition of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-5; American Psychiatric Association [APA], 2013) defines a mental disorder as a pattern of behavior that affects a person's ability to be successful in social, occupational, or other environments and causes distress. A mental disorder is often reflective of a difficulty in regulating emotions, thoughts, or behaviors caused by problems in psychological, biological, or developmental functioning. Behaviors, even dysfunctional behaviors, that are part of a normal response to significant stressors or are only viewed as deviant from society, but create no other major distress or dysfunction are not disorders (APA, 2013, p. 20).

What this definition means is that, according to the DSM-5, a pattern of behavior must have certain characteristics in order for it to be identified as “disordered.” Generally, all three must be present to qualify as a mental disorder. Specifically, they are:

- Abnormality. One basic idea of psychopathology is that the disorder is somehow different from the norm, that the behaviors represent some deviance from “normal” behaviors. After all, what would it mean to label a set of behaviors as a mental disorder when they represent behaviors exhibited by most children? But even common behaviors can be dysfunctional or distressing. Some classes in university psychology departments are entitled “Abnormal Psychology.” Is this all we are looking for—behavior that is not normal—or is there something else involved in the classification of mental disorders? Students in those classes will soon learn that abnormality is only part of the picture, and perhaps not even the most important part.

- Distress. If behaviors cause no distress to the child, to the child's caregivers, nor to the child's important environments, it might be inappropriate to diagnose the child with a mental disorder. Furthermore, distress (in and of itself) caused by one's own behavior is not sufficient to qualify the behavior as disordered. Many common and necessary behaviors are also distressing. However, behaviors that cause chronic distress do add to the difficulties in life and may even contribute to more serious illnesses including physical health. Distress is a subjective, but important, consideration in mental illness.

- Adaptive functioning. Not all behavior is useful. In fact, some might be considered useless. However, some behaviors may actually impede the ability of an individual to successfully navigate the many challenges of their life. Drinking alcohol is not necessarily a problem until the consumption of it becomes great enough to interfere with a person's ability to remain employed, pay bills, maintain interpersonal relationships, or succeed in school. When a behavior begins to decrease one's ability to succeed in important duties, it is considered maladaptive. Childhood aggression and defiance might begin to interfere with learning social and academic skills. In this sense, the aggression begins to decrease the child's ability to learn and succeed in other areas. On the other hand, a child may seem to others to be excitable and even a bit hyperactive. However, if the child remains adaptive, succeeds in school, and maintains good peer friendships, is it important to label the behaviors?

In addition to the earlier features of mental disorders, other considerations must be taken, including alternative explanations for the behaviors. If a set of behaviors has been found to be significantly abnormal, to cause significant distress, and to impede the adaptive functioning of a child, does this mean that it is appropriate to classify it as a mental disorder? Perhaps. To make this determination, it is also important to consider other possible explanations that are more mundane and not necessarily psychological. Things such as nutrition, biomedical conditions, medications, and sleep problems can result in behavior that is less than adaptive or even that appear to be a part of a mental disorder—especially in children. Before a psychological disorder is diagnosed, it is imperative that these nonpsychological problems be assessed and ruled out. Treating a child for the symptoms of ADHD (attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder) when they are actually just sleep-deprived can create unnecessary complications, or even mask a serious medical condition such as sleep apnea (i.e., the interruption of respirations during sleep).

Social relevance. Thomas Szasz (1960) suggested that it may be difficult to understand the nature of mental illnesses without a full understanding of the social circumstances under which the symptoms of mental illness emerge. For example, some Native American cultures place value on experiences (e.g., visions) that other cultures might consider symptomatic. They are not necessarily considered a problem based only on the sensory or perceptual nature of the experience. In this way, social pressures can create different probabilities that we will perceive or report our experiences in the same way. While working as a psychiatric aide as a young man, I (Fanetti) tried to remember this when dealing with people who were hearing voices. The question for me was not totally focused on the pathology of hearing voices. After all, I could not prove they were not real (think back to the Chapter 1 discussion of epistemology and the limits of proof). If that was my goal, all I could actually do was determine if anybody else was hearing them. Instead, my focus was on whether those voices were causing a functional problem. Were they causing distraction or fear? Were they asking the person to do something problematic? Remember, at no point did we prove that we were able to stop the voices; we were only able to demonstrate they the clients stopped responding to them. Maintaining a humble perspective on my own perspective has helped to differentiate troublesome pathology from nonproblematic experiences that just happened to be different than mine.

If you sat next to a man on the subway and he said (during the course of a conversation), “God just told me you are special to him,” what would you think? What would you do? Would you stop the conversation? Would you move? Now answer this: Why or why not?

Potential Causes of Mental Disorders

If we remove supernatural causes of mental disorders from our discussion (e.g., demonism, divine intervention or retribution), then we are left only natural causes to explore. This does not rule out the supernatural as possible, only as scientifically unobservable. Natural causes for mental disorders can be boiled down to three broad categories: biological, behavioral (contextual), or cognitive.

Biological Causation

There is a great deal of research to suggest that changes in physiology can have an impact on behavior, beginning with the case of Phineas Gage (Kotowicz, 2007). Gage was a mid-19th-century railroad construction foreman who experienced a serious accident. While handling explosives in preparation to excavate a pass, the material detonated and drove an iron bar through his head and out the top of his cranium, destroying a large part of the left hemisphere of his brain. Though he eventually recovered, friends and family later reported that his behavior had changed and that he was “no longer Gage.” Though actual details are sometimes hard to find, the case provided early support for the notion that brain changes and brain damage could have an impact not only on your intellectual and cognitive abilities, but also on your personality. This focus on the functioning of the brain in the display of personality has persisted in the medical community.

Parents of children who are going through the biological changes associated with puberty are also quick to identify the ways that their child's behavior has changed. When we suffer injury and pain, become intoxicated, experience hormone level changes, become fatigued, or fail to drink our morning coffee, we know our behavior changes. Part of the process of getting to know people is understanding how these things affect ourselves and those around us and beginning to be able to subsequently predict behavioral changes based on their physiological status.

Thus, it is not hard to understand why some professionals focus on physiology and biology to explain and intervene in cases of mental dysfunction. If depression becomes a problem, those who rely on biology will seek to change that biology in some fashion. The wide diversity and availability of pharmaceutical interventions is a good example. Many people can quickly name several medications thought to impact behavioral functioning, including Ritalin and Prozac. Do you know which disorders these drugs are designed to treat?

Cognitive Causation

The word cognition is derived from the Latin cogitere, which means “to think.” Cognitive theories of mental disorders often posit that more than the actual world and more than our own biology, the way we think about the world is an important factor in how we respond to it (Beck, 1970). In this way, the first line of intervention should be assessing and then changing thought patterns.

This perspective is not new. In fact, we can find traces of this in the way that ancient Persian physicians sometimes dealt with mental disorders to challenge the thought, or force the client to take the thought to its extreme (ostensibly to demonstrate the irrational nature of the thought). For example, the Persian physician Avicenna is said to have once dealt with a client who believed he was a cow. Viewing this not as a medical problem, but as a thought problem, Avicenna then proceeded to bring the “cow” to a place of slaughter. Shortly after, the client became rational and (reportedly) never had such delusions again. Although included in jest (it is a real story, though unverifiable), it nevertheless illustrates the causative thinking that Avicenna was using. The delusion was not demonic, it was not biological, it was thought-based. An argument can also be made that it was contextual, but we see that later.

The most well-known modern model of cognitive intervention was developed by Aaron Beck (1973). Beck proposed that people become depressed when they develop a pervasive set of negative beliefs about themselves and the world. Essentially, these beliefs begin to add a depressive hue to all things a person experiences, like a depressive lens through which they see the world. As they see the world to be more and more hostile, more and more defeating, they begin to retreat from it. They become depressed.

Internal Belief Systems

Core beliefs. These are our global and rigid beliefs about ourselves. Are we good or bad, attractive or ugly, wanted or unwanted, intelligent or incapable, etc.? These tend to be the products of the way we were raised, how we learned to handle barriers and the actual nature of the world as our context. That is, people who were verbally abused as children, who tend to avoid challenges (and thus successes), and live in a materially or socially impoverished environment tend to have negative views of themselves. It is difficult to change these beliefs as they are based on many years of collected experiences. Even though the experiences may be biased (e.g., we see ourselves as incapable of success even though we give ourselves little chance of success), they tend to carry heavy weight and are viewed as confirmatory. Ultimately, changing negative core beliefs into positive core beliefs is the goal of most cognitive therapies, but this is often a time-consuming enterprise.

Intermediate beliefs/thoughts. Intermediate beliefs are the predictive statements we make about the probabilities of our future experiences. They are based on our core beliefs and tend to set a kind of interpretation in motion that reflects these core beliefs, and it does not matter if the nature of the actual experience is different. One common type of intermediate belief is an if/then statement. “If I ask that girl out on a date, she will say, ‘no,’ because I am undesirable.” This kind of self-statement or belief tends to lower the probability of actually engaging in behavior challenges. After all, why would he ask her out if she is only going to say no and prove that you are unlikable? Most of us are not gluttons for punishment.

Automatic thoughts. Automatic thoughts are the immediate statements we make to ourselves upon encountering a challenge, or experiencing a failure or success. They are based on our core beliefs in that they reflect our self-concept. They are often the product of the interpretive biases created by those if/then intermediate thoughts we had earlier. So if the above man was negative about asking a girl out on a date, what would happen if he did? If she said yes, he may be likely to think (i.e., automatically and to himself), “Well she sure is charitable. She must be to say yes to me.” If she says no, he may be likely to think, “That's what I thought. I don't blame her. Why would she want to go out with me?” In either case, the man's immediate thoughts tend to support his core beliefs and the predictions made in his intermediate beliefs. Whether he got the date or did not, his automatic thoughts are likely to reflect his core beliefs. Cognitive theorists would say that this individual is likely to be or become depressed over time.

Contextual/Behavioral Explanations

As discussed in Chapter 2, contextual explanations for behavior focus on environmental conditions that serve to encourage or support behavior. Children may learn behavior patterns observationally, by watching how parents, teachers, and friends conduct themselves. If this behavior also is followed by sufficient reinforcement, then it will continue. According to operant conditioning theory, any behavior that exists or continues to exist is being reinforced in some fashion (Skinner, 1938; Thorndike, 1913). The goal of the behavioral interventionist is to identify the ways that a behavior is being supported (or not supported) by contingencies and then make changes to the environment or context that support the most appropriate behaviors.

Chapter 2 discussed the processes of operant conditioning in some detail. These principles are thought to impact all living creatures. This means that even if a person is experiencing a serious mental disorder, they are still bound to the Law of Effect. Their behavior is still supported by reinforcers that exist in the environment. Children with autistic disorder may experience a great deal of difficulty with learning and social interaction. There is little doubt that the causes for the disorder are neurological. However, the best interventions remain behavioral and focused on providing sufficient reinforcement to support adaptive behaviors (Lovaas, 1987).

Diagnostic Systems and Methods

Categorical and dimensional methods. What makes a child's behaviors diagnosable? Perhaps the child's behaviors are just very unusual and rarely seen in normal child development. This is certainly possible and would support the notion that some disorders should be considered as categorically different than other behaviors. In fact, this categorical approach is the dominant perspective in most diagnostic labeling systems. These systems attempt to identify the most common behaviors associated with a specific disorder and then group (i.e., categorize) those individuals. Thus, you may hear people discuss the disorder, rather than the person. For example, once a person says, “John has ADHD,” the term ADHD begins to exert a definitional pressure on John. For conversational purposes, this may be acceptable because it abbreviates the discussion. However, professionals who need to understand or help John will have a much greater need for information than is provided in the label. As we see when we investigate the DSM and ADHD, the label says little about the specific problems John faces, because there are many different patterns of behavior that can each yield a diagnosis of ADHD, and many different severities.

Conversely, many psychologists advocate using a dimensional approach to diagnosis. A dimensional approach assumes that behavior can be understood in terms of its probability or frequency. Furthermore, it assumes that the existence of a behavior is not automatically problematic. Instead, problems arise when the behavior becomes too frequent or too severe. Have you ever been working on a task, surrounded by noise, and “heard” someone call your name or ask a question only to be told nobody said anything? Is this a normal experience? No real data exists on how frequently this actually happens, but it is assumed that most people have had the experience. Technically, it might be considered a hallucination (i.e., a sensory or perceptual experience without environmental cause). However, hallucinations only become diagnosable when they are frequent enough and severe enough to cause difficulty in adjustment. One extreme of the quantitative dimension for hallucinations is the observation that they are completely nonexistent (i.e., a zero-percent frequency). This is probably rare. The other extreme is that the experience of hallucinations is so severe in terms of frequency or magnitude that they are highly disruptive to everyday functioning. This is also probably rare. Most people will fall somewhere between those two extremes—somewhere along that dimension. Many psychologists are primarily interested in a simple assessment of frequency and severity of a hallucination, rather than dichotomous statements about its presence. These frequencies can then be compared to normalized distributions of the same behavior for other children of the same age, to determine if they are more frequent for a particular child.

However, it is difficult to use a dimensional system of diagnosis when behavioral measurements are elusive or when the normalized base rates of behaviors are unavailable. Furthermore, these dimensions do not necessarily preclude the ultimate use of a categorical diagnostic system. However, thinking dimensionally when considering the occurrences of problematic behavior can help any professional to avoid automatically pathologizing a child that would better benefit from a focus on specific behaviors.

The DSM System

The most ubiquitous tool in psychology or psychiatry for psychopathological diagnosis is the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, usually abbreviated as the DSM. The first DSM (DSM-I) was published in 1952, followed by revisions in 1968 (DSM-II), 1980 (DSM-III), 1987 (DSM-III-R), and 1994 (DSM-IV). A slight set of modifications to the supporting text, but not the diagnostic criteria, yielded the DSM-IV-TR in 2000. In 2013, the DSM-5 was released.

The DSM was designed to be a system for aggregating patterns of behavior into diagnostic categories. Most diagnostic categories in the DSM are assigned by comparing the symptoms exhibited by an individual to lists of potential symptoms, described by “working group” panels of experts. These experts decide which symptoms are required for each diagnostic category. If the symptoms of the individual match the lists provided by the DSM, the diagnosis can be assigned.

Well…almost. Because most (but not all) symptoms are actually expressions of normal behaviors that have become maladaptive in some fashion (e.g., intensity, duration, contextual appropriateness, or distress), the DSM usually requires the diagnosing professional to assess the degree to which the behaviors are maladaptive and cause significant distress. That Goth or Punk teenager who lives down the street may seem odd to some people. He or she may engage in behaviors that are outside the norm, like wearing vampire makeup or sporting spiked hair. These teens may also seem more withdrawn than other students, or more ill-tempered and suspicious. However, if they have no problems with social, academic, or occupational functioning that are outside the norm (remember that many young people have trouble learning to adapt in adolescence), if they are not in distress about their own behaviors and are not causing significant distress to others (e.g., thinking that they are strange is not distress), then they can usually not be classified as having a psychological disorder. Essentially, we are all allowed to be eccentric without the worry of having others label our behavior in ways that carry legal and social consequences.

Developmental Pathways

Finality. Another difficulty for understanding the causes of problematic behaviors in childhood stems from the various developmental effects that rearing environments can exert. Cicchetti and Rogosch (2002) describe two different developmental pathways that make causal statements in child psychodiagnosis particularly difficult.

Multifinality. Single events that are thought to be problematic do not always lead predictably to the same outcome. In fact, traumatic events, abusive experiences, and harsh environments can lead to one of many different types of behavioral outcomes. There is not one certain pathway between an event and its outcome.

Equifinality. If multifinality was not enough of a problem, there is more. Equifinality is the idea that similar problematic behaviors do not always arise from a specific causal events. In fact, many different types of problematic events can lead to the same set of behaviors. So we cannot reason backward from a set of behaviors to identify their cause.

Violent and Disruptive Behavior in Children

Elliott and Tolan (1998) attempted to provide a categorization of violent behaviors, especially those seen in groups of young people. Though all violence is a concern, their idea was to differentiate the least and most worrisome types of violence.

Situational violence. Situational violence is often reactive. Sometimes people find themselves or place themselves in environments where they encounter threats. Normally they may be calm and peaceful, but in these environments they resort to physicality to respond to perceived threats. Interventions with reactive, situational violence are straightforward: Remove the individuals from the situation and help them better understand the consequences for being in that context. Additionally, help them learn new skills that can defuse, rather than escalate, situations and thus avoid the anger and violent responding.

Relationship violence. Relationship violence is that which arises as a function of long-term relationships. Sometimes nonviolent people remain in interpersonal relationships that they find frustrating and anger-provoking. Difficulty with effective problem solving and communication complicates this problem. Intervention in this type of violence requires either an improvement in the communication between the individuals (so that the frustration subsides enough to prevent violence) or to remove the people from the relationship. However, it may be preferable to improve communication skills in either solution, because new relationships may suffer from the same dysfunction if communication remains troubled.

Predatory violence. Predatory violence is violence used to affect some goal or gain. These goals can be either material (e.g., money or goods) or they can be interpersonal (e.g., to intimidate others into compliance, or bullying). Unlike situational and relationship violence, predatory violence is usually a planned choice. That is, it is used as a tool rather than as an automatic reply or response. This planfulness makes this kind of violence particularly worrisome to others, including law enforcement agencies. However, because the violence has a functional goal, then the intervention simply requires an alteration of the effectiveness of the behavior. In other words, if the violence no longer creates the intimidation or the cost of the violence is sufficiently high, then the individual will seek other (hopefully nonviolent) means to affect that goal. Education and skills training are useful tools to help these people learn alternative strategies while also maintaining the high cost of the violence for them.

Psychopathological violence. Psychopathological violence is the most worrisome because it involves violence as a self-rewarding behavior. The pleasure or satisfaction of the violence becomes the goal. It is self-reinforcing. Individuals who engage in psychopathological violence do so because they enjoy the process. It may be that they enjoy the experience of frightening others, or actually harming them. In either case, it will be difficult to intervene in a way that changes this dynamic. Although the predator may use violence as a means to an end, for the psychopath, violence is the end.

Types of Legal Violations

Status violations. Status crimes are those that are illegal only for people of, or without, a certain status. For example, many behaviors are legal only for adults, including drinking alcohol, smoking cigarettes, failing to attend school, or adult sexual entertainment. Any child who voluntarily engages in these activities is committing a status offense. Because they are allowable for some people (e.g., adults) they are often viewed as less serious. Many times the limitation is placed simply for the well-being of the child. Even so, commission of many or repeated status offenses can be an indicator of more serious problems and may eventually lead to more serious types of offenses.

Index violations. Index crimes are those that are illegal for any person. For example, there are no circumstances under which crimes such as vandalism, stealing, assault, rape, or murder are legal. Although there is a range of severity that needs to be considered, index offenses are generally of more concern than status offenses. In the expected progression of conduct problems, those children who have started to commit index offenses are more likely to progress into more serious offenses unless intervention is offered and is effective.

Dimensions of Disruptive Behavior

Externalizing behaviors can be understood when viewed on one of several dimensions of behavior. Each of these dimensions is used to place the behavior in relative comparison to other behaviors.

Delinquent versus aggressive (Achenbach, 1991). For example, the first dimension often used is delinquent versus aggressive behavior. On this dimension, behaviors to one extreme are highly aggressive and are actively encroaching on others' rights. Behaviors existing on the other side of this dimension are called delinquent. Delinquent behaviors are those that are somewhat passive and usually involve a failure to meet some obligation. Assault is aggressive, while skipping school is delinquent.

Overt versus covert (Frick et al., 1993). The overt versus covert dimension is used to identify how visible the problem behaviors are. Behaviors such as lying and stealing are more covert. Children engaging in these behaviors are often trying to hide them from others. In contrast, bullying and assault are overt behaviors. Little to no effort may be made to hide these behaviors from others, unless those others are authority figures with the power to intervene.

Destructive versus nondestructive (Frick et al., 1993). Another acknowledged dimension of conduct disordered behavior involves the amount of damage the behavior creates. Although the damage does have to be real (e.g., vandalizing a building), it does not have to be material. For example, spreading rumors about another person to cause them social harm or damage can be considered a destructive behavior.

Though children's behaviors often start with those that are delinquent, covert, and nondestructive, it can be expected that they will gradually become more overt, aggressive, and destructive if intervention does not happen. How far and for how long they are allowed to progress into these more serious behaviors is indicative of prognosis.

Patterson's Early Starter Model

Many children exhibit some conduct problems during adolescence. Many children also stop those behaviors when they become an adult. Sometimes intervention is necessary, but often the cessation of these behaviors seems almost spontaneous. On the other hand, some children will continue to display these problem behaviors well into their adulthood, perhaps even escalating the severity of their behaviors. Recovery may be unlikely for some and require significant intervention for others.

Gerald Patterson, Capaldi, and Bank (1980) attempted to determine if there was a way to differentiate these generally difficult or persistent cases from the less worrisome cases. This determination can be made post hoc (i.e., after the conclusion) but that offers little insight into how to help children before they have traveled too far down the road to ruin.

Patterson et al. (1980) were able to determine and empirically demonstrate that many of these cases can be differentiated based on when the earliest signs of trouble began to be noticed. They were able to show that some children only began to display serious conduct problem during adolescence. They were often noted to have had normal early childhoods, normal academic experiences, and fewer difficulties in family life. They also typically had a better prognosis and tended to limit their problem behaviors to less catastrophic varieties, often staying with more serious status offenses and avoiding more serious index offenses.

On the other hand some children began having conduct problems very early, sometimes in early elementary school or even earlier. In their histories was more indication of conflict, family discord, and academic difficulty. These early starters were more likely to commit more serious offenses and were also more likely to continue having trouble into adulthood.

Interventions With Patterson's Model

Behaviorists believe that nearly every behavior can be understood in terms of the environmental context in which it occurs. In this case, the reinforcers for behavior are relevant. The idea is that making sure that a child's choices are guided by reinforcers (or punishers) that are effective is useful. If we know the benefits and costs of our choices and those attributes are well known, then behavior should conform to that plan. Perhaps we can just create a more structured and predictable environment. Well, it turns out that this is fairly effective with late starters, but less effective with early starters. On reflection, the reasons may be easy to understand.

Late starters often have a childhood in which they were successful at acquiring and using skills: social skills, family skills, and academic skills. However, when they arrived at adolescence, the consequences that support the use of those skills changed and began to support more problematic behaviors. Consequently, if we effectively alter the environment to once again support positive skills and behaviors, then the child should have the abilities needed to exhibit those behaviors and change is more likely.

Those early starters may not be so easy. During their more tumultuous childhood, they may not have acquired those skills or developed any proficiency with them. It is difficult to develop academic skill when much of your time is spent in the principal's office or in the hallway. It is hard to develop positive social skills when your family has relied on coercive behavior and you have relied on coercive behaviors to deal with your peers. So, simply changing consequences will not work. If you told a person who has never seen an engine, “I'll give you $1,000 if you replace this engine,” would you expect them to be able to do it? Probably not. They do not know how. In order for that car repair to happen, we will need to offer both an incentive (e.g., the money), but we will also need to teach them how to do it (e.g., the steps of the skill). This is how to view intervention with early starters. It will require a careful examination of the contingencies in the child's life, as would an intervention with a late starter. But in addition, the early starters will need various skills training. They will need to learn how to study, how to withhold angry responses, how to resist illegal behaviors, how to understand other people's perspectives, and so on. This is a much more complex task. Professionals who are first learning about a child who is engaging in illegal or conduct disordered behaviors will often find valuable information in determining when these things started, using that information to assess the contextual environment as well as the child's knowledge and usage of social and academic skills. This assessment offers the best opportunity to help both groups.

Risk and Resilience

Why is it that some children emerge from impoverished and difficult childhoods to become productive and well-adjusted adults, while other children from the same environments do not? We can even imagine two neighbors, both with similar family financial status and both with similar family supervision. These neighbors go to the same schools and graduate at the same time. In every externally observable way they led similar lives. However, one goes on to higher education and one becomes a prison inmate.

All of those externally observable barriers are known as risk factors. Risk factors are general variables that are known to be associated with poor outcomes. For example, low socioeconomic status (i.e., SES) is known to be associated with a host of problematic outcomes that range from health problems to legal problems. We may sometimes be tempted to believe that the risk factor is the problem. After all, if we can eliminate poverty, would we not also eliminate the host of associated problems? Eliminating risk factors is either a hugely difficult endeavor or it is impossible. Instead, some researchers suggest that we look not at the risk factors (though efforts to reduce poverty remain worthy), but we instead examine the factors that produce positive outcomes—even when risk factors are present. In the earlier example about neighbors, we can look at the effects of risk factors on the boy who went to prison or we can try to determine why the other boy was able to rise above the risk.

Michael Rutter (1987) suggested that instead of examining risk with a singular focus, health professionals should examine the experiences that either make the risk produce negative outcomes or the factors that shield us from the risk to produce positive outcomes. In other words, why do good things happen in bad places? If we can figure this out, then perhaps we can repeat the process. For Rutter, there are at least four important concepts which can help us to understand why some do better and some do worse: risk, resilience, protective factors, and vulnerability mechanisms.

Risk is the presence of problematic environmental, personal, or inter-personal experiences. Risk is known to be associated with poor outcome. Resilience is the experience of positive outcomes, in spite of the presence of risk factors. It does not explain why the individual experienced the positive outcome—just that he or she did. Protective factors are those experiences that appear to increase resistance to risk and provide for resilient outcomes. For example, parents who insist on effort in school work may provide for their children a mechanism by which they can escape poverty in the future. Vulnerability mechanisms are those experiences that tend to increase the power of the risk factors. For example, children who endure impoverished environments may also be burdened with parents who are addicted to alcohol or other substances. This addiction may cause a greater void in parental supervision or may increase the probability of the extra burden of abuse. In addition to the barriers presented by the primary risk factor, vulnerability mechanisms make resilience less likely.

Ecological Systems Theory

Why is it that some children can seem to follow the rules while in school or while at their family home, but exhibit more problematic behavior when away from those environments with their friends and peers? Most parents, professionals, and adults already understand that the rules seem (to these children) to be different in each environment. Behavior that is acceptable in the family environment may be not be appreciated by peers, when the peers are away from family and school. For example, children quickly learn how to use slang or foul language when with peers, but refrain from its use at home or school. Then how do we change problematic behavior, if it will be supported in a different environment as soon as the child leaves the therapeutic environment?

For Urie Bronfenbrenner (1986), the answer first lies in the way that we understand the influences that are being exerted in each environment. Bronfenbrenner developed the Family Ecological Systems theory to explain the divergent patterns of support that exist in different aspects of a child's life. In this theory we must first understand the concept of systems and how they operate together and independently, before we can apply an appropriate style of intervention for disruptive behaviors.

A system is an environment in which the rules for behavior are defined by a single context, such as the family system, the school system, or the peer system. In each of these systems, an individual comes to understand which behaviors will be supported and which will not be supported. Their behaviors begin to conform to the rules set up by the players in that environment. This can be referred to as a microsystem, as it is often the most basic level system.

These systems are not usually completely independent, especially in young childhood. Children of preschool age rarely have friends with whom they interact when their parents are not present. Therefore, for them the peer system and family systems are highly overlapping. Furthermore, when children do first attend kindergarten, parents are often communicative with the teacher and somewhat involved in the child's education. In addition, while a child's peer group may expand during this time, it remains highly overlapping with both the family system (e.g., parents attend other children's birthday parties) and the school system (e.g., elementary school teachers are almost always monitoring children during the day). This overlapping of systems in which the rules for two or three systems comingle are called mesosystems.

Other systems also affect a child's life and behavior. Exosystems are those systems that affect the major rule setters in a microsystem but are not always observable to the child. Parents' bad days at work may affect the way they support certain behaviors at home. Although the child may not be privy to this bad day for the parent, they indirectly feel the effects of it. For the child, the parent's external experiences create an exosystem.

Macrosystems are those that surround and set the stage for all other systems for the child. Macrosystems can be things such as culture, community, and poverty. These systems have a general effect on other systems. Alterations to culture or community (e.g., the rapid changes created by the terrorist attacks in New York City in 2001) can significantly change the behaviors that are deemed appropriate or inappropriate.

Changes in Systems as Children Mature

As discussed earlier, the mesosystem status of young children tends to be highly overlapping. As children develop, these systems may begin to pull apart and separate. As children age, they may be given more opportunity to play with friends without direct supervision. As that happens, there may be more “pure” peer system influence. Consider the young teenager who first attends high school. Here there is less teacher supervision (e.g., teens tend to be responsible for getting themselves to classes) and more independent peer interaction. Adults are not listening all that closely to the conversations occurring in the hallways. After school, there are more opportunities to interact with peers outside of school and home (e.g., an afternoon at the mall). As children mature, they spend more time with their peers and in more environments with less oversight by parents and teachers. Overall, the peer system begins to grow in size and independence—and thus influence. If this peer system is functional and reasonable then the influence is not problematic. However, when this peer system includes dysfunctional peer group members, the newly found power of the peer system may begin to exert greater influence or carry over into the child's general behavioral dispositions. Normally, this growing independence is a healthy part of development.

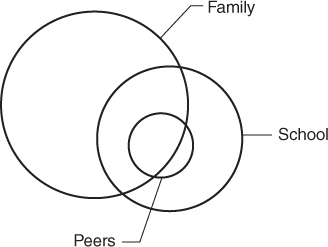

Figures 3.1 to 3.3 illustrate the relative size and overlap of the three major microsystems in a child's life during three distinct developmental periods. Figure 3.1 emphasizes the kindergarten period. During this period, the family system remains most influential, but the school system gains considerable influence. The peer system exists (usually) completely within the family and/or school systems. That is, interactions with friends are normally also observed and guided by parents and/or teachers. Rare is the opportunity for children to interact completely outside of the observations of adults.

Figure 3.1 The Child's Systems During Kindergarten

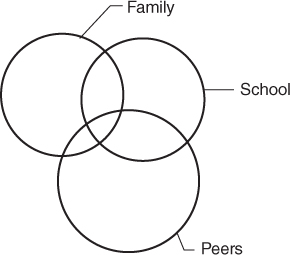

Figure 3.2 The Child's Systems During Elementary School

Figure 3.3 The Child's Systems During High School

Figure 3.2 represents possible systemic balances as children develop through elementary school. Family and school systems remain influential, but the child may build a larger network of peers. In addition, they may be able to interact with these peers more frequently outside of the observations of adults. On the playground, teachers may not be hovering and may only observe from afar. At home, parents may be more willing to let children play by themselves outside or otherwise away from direct supervision. This newly growing peer group, which is also gaining some independence, may begin to exert greater influence on the child's behavior. Here they begin to learn words they did not learn at home or school and may pick up mannerisms from friends.

Figure 3.3 represents a possible balance of systems for a child during high school. Notice that the power of the peer system has grown in comparison to the family and school systems. It has also gained considerable independence. Now children spend a good deal of time with peers and not within observation of parent and teachers. In some cases, this peer group may become more influential than the family or school system. At this point, parental or school influence becomes difficult. In essence, these systems may no longer be capable of exerting enough influence to overcome the power of the peer system. If the peer system is working in ways that are at odds with the goals of the family system or school system, then parents and teachers may experience frustration as their influence wanes.

Multisystemic Therapy (MST)

Multisystemic therapy (MST) is a multifaceted form of intervention for children who are at risk in several systems and have become disruptive or violent. Of primary importance in this therapy approach is Bronfenbrenner's conceptualizations of systemic interdependence. Primarily, MST requires one therapist to enter into each of the primary systems of the child and help to create a similar set of rules and skills in each system. Specifically, the therapist will engage in family therapy to help ensure that the child's parents are able to provide stability, and can help to model and support the appropriate behaviors. Additionally, the therapist will also work with the child's school environment to help teachers and administrators understand how to help the child stay in the social school environment and succeed in both behavioral disposition as well as academic competence. Finally, the peer system remains. If the peer system continues to support problematic behaviors, then it will work against the progress that is possible in the other systems. Therefore, it becomes necessary (especially when the children's behaviors are serious and illegal) to restructure the children's peer environment, to change their peers. MST often accomplishes this through the use of after-school centers monitored by staff members who also serve as tutors and social skills trainers.

In this way, MST has been effective at reducing recidivism, the tendency to reoffend after intervention, even in more violent youth offenders (Henggeler, 2011; Klietz, Borduin, & Schaeffer, 2010; Sawyer & Borduin, 2011). However, while formal MST is the most supported intervention for serious and violent offenders, the same principles apply to all children and can be used to understand why some attempts at intervention fail. Therefore, understanding MST and Bronfenbrenner's systems theory are good places to start when conceptualizing any specific case.

Father Flanagan's Girls and Boys Home (i.e., Girls and Boystown USA) in Omaha, Nebraska uses a modified version of this idea (Dowd & Tierney, 2005), which even predates the development of MST. When children are admitted to the facility they stay in homes run by family teachers. These teachers are married and often have children of their own staying in the home. They live at this home permanently. They become the well-trained authorities in the new family system. Additionally, every child attends schools run by the facility. These teachers are trained in the same model of intervention as the family teachers. Finally, the campus is a large facility with more than 500 children. These children range from new admits to experienced attendees who can serve as proxy authorities. The peer environment is supportive, rather than destructive. With three well-designed systems that communicate regularly, Father Flanagan's is the best example of an effective MST or Bronfenbrenner application.

Disorders of Interest to Forensic Professionals Who Work With Children

Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD)

Children can be energetic, especially when viewed through the lenses of the adult parents. Excitement and anticipation can sometimes be more than a child's self-control can tolerate and the result is behavior that would be excessive for older individuals. Often while walking with my 6-year-old daughter to the store, she will…prance. She may even sing a song while hopping along and holding my hand. Nobody even gives a second glance. It is normal. It is cute. However, when Dad decides to play along and we both skip along the sidewalk, people look. I suspect nobody wants to see a 45-year-old man skipping—though I get enough leeway when I'm with my daughter. (I have not yet tried it without her.) Most adults look at such displays as unusual, because it requires so much energy. It is fine for kids who have bundles of energy, but strange for adults who are assumed to have less.

However, there is some limit to the allowable excessive behavior of children that people will tolerate. In fact, Western society has been attempting to understand the difference between youthful exuberance and dysfunctional overactivity for many decades, or even millennia. The genesis of the diagnostic category we now refer to as attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder, ADHD, can be found in research dating to the early part of the 20th century. In 1902, George Still described overactive behaviors found in children as the result of low “inhibitory volition,” suggesting that they suffered from a lack of ability to voluntarily stop themselves from acting out. Furthermore, and as a reflection of the late Victorian culture, he also described the behaviors as reflecting “defective moral control.” Victorianism often combined the concepts of inhibition and morality, thus conflating immorality or amorality with excessive behavior.

A series of encephalitis epidemics in the late 1910s began to lead researchers toward a more biological explanation of hyperactive behavior. These children, who had suffered objective brain injury as a result of encephalitis or other traumas, often exhibited behaviors such as hyperactivity, impulsivity, and an irritable interactional style. Within two decades researchers began to believe that children with these behaviors, but no obvious source of brain trauma, must nevertheless also be suffering from neurological brain damage. This led to the introduction of the label minimal brain dysfunction (MBD) as a way to categorize children with hyperactive and impulsive symptoms, but no obvious cause (Strauss & Lehtinen, 1947).

In the 1970s, researchers began to suggest that hyperactivity and impulsivity were not the only symptoms related to each other in overactive children, but that inattention was also a part of the mix (Douglas, 1972), which led to the “dual symptom” categories of ADHD that we use today. At the same time, a theory was developing that the cause for these symptoms, while still brain-related, was in fact systemic autonomic underarousal. The resultant behaviors were a direct result of the brain attempting to correct for this by autostimulating. In the same way that others can become agitated, fidgety, and inattentive when we are very fatigued, it was thought that children with hyperactive and inattentive symptoms in fact needed stimulating intervention. Early work with stimulants including Ritalin ensued (Sykes & Douglas, 1972).

The most modern (biological) ideas about the causes of ADHD do not focus on autonomic stimulation, but rather on prefrontal cortical stimulation (Barkley, 1996). It is thought that the prefrontal cortex (i.e., the area of your brain roughly in your forehead) is responsible for inhibiting behaviors momentarily as we apply memory and planning. This is called executive function. Without this ability, we are often left to react impulsively with responses that are automatically reinforcing, but carry long-term disadvantages. It becomes difficult to screen out novel or interesting stimuli and makes it difficult to concentrate on more difficult tasks, such as listening to lectures or reading a textbook. Interestingly, stimulant medications are also thought to work by increasing neural activity in the brain, but the presumed primary locus of that effect has simply moved.

The diagnostic criteria for ADHD (APA, 2013) describe two primary types of symptoms that are important to diagnosis: symptoms of inattention and symptoms of hyperactivity/impulsivity (p. 59). An example of one of the nine potential symptoms of inattention is, “Often has difficulty sustaining attention in tasks or play activities” (p. 59). Eight of the nine symptoms are quantified by the word often. The goal is to identify children who seem to have more trouble than other children in focusing on tasks that are difficult or nonrewarding.

Hyperactivity and impulsivity is characterized by children's difficulty in regulating their behavioral responses at appropriate levels or a difficulty in inhibiting responses to situations in which the response might be viewed as inappropriate. An example of a symptom of hyperactivity in the DSM (2013) is, “Often talks excessively” (p. 60). Again, all nine of the DSM symptoms of hyperactivity or impulsivity are quantified using the word often.

The DSM also provides for a specification of whether the child's symptoms are mostly from one category (i.e., “predominantly hyperactive/impulsive” or “predominantly inattentive,” p. 60) or are more evenly distributed across the categories (i.e., “combined,” p. 60).

Criticisms of the ADHD category include the difficulty in implementing the word often in normal practice to differentiate problematic childhood behaviors from those that are a part of the spectrum of normal child behaviors. In essence: What is “often”? Other criticisms are related to the focus on neurology as the primary facilitator of hyperactive behaviors, which may lead to an undervaluing of environmental factors as causal ingredients or intervention possibilities.

The DSM-5 (2013) organizes other childhood behavior disorders as “disruptive.” The first is oppositional defiant disorder, that is, ODD (p. 462). According to the DSM, ODD is characterized by a mood state that is often angry and behaviors that are defiant and confrontational (p. 462). Children with ODD cause disruption in educational and family environments. They may begin to create (or be the product of) hostile environments, which ultimately provide more reinforcement and support for coercive behaviors than cooperative behaviors (Patterson, 2002). If these behaviors begin to generalize to peer relationships and the general community, the child may be at risk for the more serious behaviors associated with conduct disorder.

Conduct Disorder

Conduct disorder (CD) is a serious disorder of childhood and adolescence that typically includes behaviors that violate the rights of others or violated the rules, laws, and expectations of society in such a way as to make community response necessary. Many times these behaviors include forms of violence discussed earlier in this chapter or true index violations (things that are illegal for people of any age). An example of the symptoms reflected in the DSM-5 (2013) criteria include, “Often bullies, threatens, or intimidates others” (p. 468). Although these behaviors also sometimes rely on the quantifier often, it might be argued that the behaviors themselves are so much more aggressive and unusual that those of ADHD or ODD that they become easier to identify. A second example that reflects the greater severity of these criteria is, “Has forced someone into sexual activity” (p. 470).

According to Patterson's coercive systems model (Patterson, 2002), these behaviors, if left unchecked, may put the child at risk to continue the disruption into adulthood, and into more serious interactions with society. Some may develop adult antisocial personality disorder (APD), which is characterized impulsive behavior, habitual lying, violating others' rights, and a lack of remorse for transgressions. Prison populations are often heavily populated by adults with diagnosable APD (Hare, 1983). But what differentiates those adolescents at greatest risk for continuing problems from those who are more likely to eventually cease the behavior or respond favorably to intervention? Evidence is not yet clear on the answer to this question.

Study Questions

- Explain the three features of behavior that usually must be present to diagnose a mental disorder.

- Explain the differences among the ideas of biological, cognitive, and behavioral causation.

- In the cognitive model, explain core beliefs, intermediate beliefs, and automatic thoughts.

- What is the difference between a categorical and a dimensional model of psychopathology?

- Explain multifinality and equifinality.

- Describe the four classifications of violence offered by Elliott and Tolan (1998).

- Describe the three “dimensions” of conduct problems.

- Explain the concepts of risk, resilience, protective factors, and vulnerability mechanisms.

- According to Bronfenbrenner, what are systems? Next, explain microsystems, mesosystems, exosystems, and macrosystems.

- Without memorizing the symptoms, describe the disorders of ADHD, ODD, and CD.

Glossary

- abnormality

- The degree to which a behavior is different from that which is expected by a society or group of people.

- adaptive functioning

- The degree to which a behavior does or does not prevent behavior functioning that allows a person to successfully navigate the necessities of daily life.

- behavioral explanations

- The degree to which learning processes can be used to explain behavior.

- biological causation

- The degree to which biological factors can be used to explain behavior.

- categorical models

- Models used to diagnose mental illness, which rely primarily on group assignment.

- cognitive causation

- The degree to which thought-based processes, especially in humans, can be used to explain behavior.

- dimensional models

- Models used to diagnose mental illness, which rely primarily on the severity, magnitude, or frequency of behaviors compared to norms.

- distress

- The degree to which a behavior causes psychological pain or difficulty to the person or his/her significant others.

- early starters/late starters

- A prognostic indicator for children who are diagnosed with conduct disorder. Early starters tend to have a worse prognosis than late starters.

- equifinality

- Similar problematic behaviors do not always arise from a specific causal events.

- multifinality

- Single events that are thought to be problematic do not always lead predictably to the same outcome.

- risk/resilience

- The idea that some children emerge from difficult environments (risk) with productive healthy lives (resilience).

- social relevance

- The degree to which a behavior is reflective of the motivations and support of a person's social environment.

- systems

- Bronfenbrenners's idea that behavior can be affected by differing factors across situations. For example, children may behave differently when with peers, family, or at school.

References

- Achenbach, T. (1991). The Child Behavior Checklist and related instruments. In M. Maruish (Ed.), The use of psychological testing for treatment planning and outcomes assessment (2nd ed., pp. 429–466). Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum.

- American Psychiatric Association. (2013). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (5th ed.). Arlington, VA: American Psychiatric Publishing.

- Barkley, R. (1996). Linkages between attention and executive functions. In G. Lyon & N. Krasnegor (Eds.), Attention, memory, and executive function. Baltimore, MD: Paul H. Brookes.

- Beck, A. (1970). Cognitive therapy: Nature and relation to behavior therapy. Behavior Therapy, 1(2), 184–200.

- Beck, A. (1973). The diagnosis and management of depression. Oxford, England: University of Pennsylvania Press.

- Bronfenbrenner, U. (1986). Ecology of the family as a context for human development: Research perspectives. Developmental Psychology, 22(6), 723–742.

- Cicchetti, D., & Rogosch, F. (2002). A developmental psychopathology perspective on adolescence. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 70(1), 6–20.

- Douglas, V. (1972). Stop, look and listen: The problem of sustained attention and impulse control in hyperactive and normal children. Canadian Journal of Behavioural Science, 4(4), 259–282.

- Dowd, T., & Tierney, J. (2005). Teaching social skills to youth (2nd ed.). Omaha, NE: Boys Town Press.

- Elliott, D., & Tolan, P. (1998). Youth violence prevention, intervention, and social policy: An overview. In D. Flannery & C. Huff (Eds.), Youth violence: Prevention, intervention, and social policy. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Publishing.

- Frick, P., Lahey, B., Loeber, R., Tannenbaum, I., Van Horn, Y., Christ, M.,…Hanson, K. (1993). Oppositional defiant disorder and conduct disorder: A meta-analytic review of factor analyses and cross-validation in a clinical sample. Clinical Psychology Review, 13, 319–340.

- Hare, R. (1983). Diagnosis of antisocial personality disorder in two prison populations. American Journal of Psychiatry, 140(7), 887–890.

- Henggeler, S. (2011). Efficacy studies to large-scale transport: The development and validation of multisystemic therapy programs. Annual Review of Clinical Psychology, 7, 351–381.

- Klietz, S., Borduin, C., & Schaeffer, C. (2010). Cost–benefit analysis of multisystemic therapy with serious and violent juvenile offenders. Journal of Family Psychology, 24(5), 657–666.

- Kotowicz, Z. (2007). The strange case of Phineas Gage. History of the Human Sciences, 20(1), 115–131.

- Lovaas, I. (1987). Behavioral treatment and normal educational and intellectual functioning in young autistic children. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 55(1), 3–9.

- Patterson, G. (1982). Coercive family practices. Eugene, OR: Castalia.

- Patterson, G. (2002). The early development of coercive family process. In J. Reid & G. Patterson (Eds.), Antisocial behavior in children and adolescents: A developmental analysis and model for intervention. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association.

- Patterson, G., Capaldi, D., & Bank, L. (1980). An early starter model for predicting delinquency. In D. Pepler & K. Rubin (Eds.), The development and treatment of childhood aggression (pp. 139–168). Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum.

- Rutter, M. (1987). Psychosocial resilience and protective mechanisms. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry, 57(3), 316–331.

- Sawyer, A., & Borduin, C. (2011). Effects of multisystemic therapy through midlife: A 21.9-year follow-up to a randomized clinical trial with serious and violent juvenile offenders. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 79(5), 643–652.

- Skinner, B. F. (1938). The behavior of organisms: An experimental analysis. Oxford, England: Appleton-Century.

- Strauss, A., & Lehtinen, L. (1947). Psychopathology and education of the brain-injured child. Oxford, England: Grune & Stratton.

- Sykes, D., & Douglas, V. (1972). The effect of methylphenidate (ritalin) on sustained attention in hyperactive children. Psychopharmacologia, 25(3), 262–274.

- Szasz, T. (1960). The myth of mental illness. In B. Gentile & B. Miller (Eds.), Foundations of psychological thought: A history of psychology. (pp. 113–118). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

- Thorndike, E. (1913). Associative learning in man. In E. Thorndike (Ed.), Educational psychology: The psychology of learning (pp. 138–152). New York, NY: Teachers College Press.