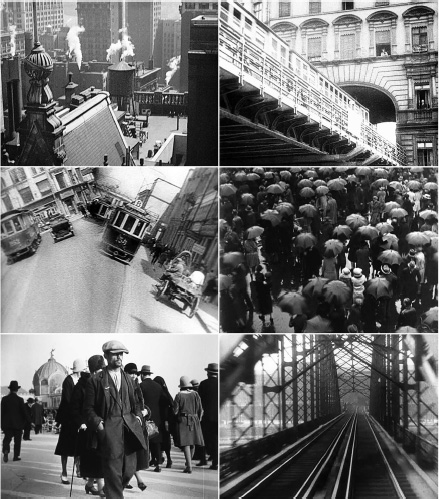

The 1920s and 1930s saw the rise and development of dozens of films that were labeled city films, city poems, or, more commonly, city symphonies. Well-known examples include Manhatta (Paul Strand and Charles Sheeler, 1921), Berlin: Die Sinfonie der Grosstadt (Berlin: Symphony of a Great City, Walter Ruttmann, 1927), Chelovek s kinoapparatom (Man with a Movie Camera, Dziga Vertov, 1929), Regen (Rain, Joris Ivens and Mannus Franken, 1929), and À propos de Nice (On the Topic of Nice, Jean Vigo, 1930). These films helped to invent the avant-garde nonfiction film by handling documentary footage of the modern city in ways that could be abstract, poetic, metaphorical, and rhythmic. Instead of serving as a mere backdrop for a story, the city, here, is the protagonist of the film—it is its primary focus, its impetus, the very material of which the film is fashioned. In addition, the city symphony recognizes the city as an emblem of modernity (perhaps the ultimate emblem of modernity), and its modernist form represents an attempt on the part of the filmmakers to use the rapidly expanding language of cinema to capture what László Moholy-Nagy once called “the dynamic of the metropolis.”1 The vast majority of these films are notable for their oftentimes imaginative, even daring, use of editing, and this cycle as a whole made a major contribution to the discourse of montage aesthetics that was such a crucial aspect of the interwar period, deeply affecting the realms of film, the visual arts, literature, theater, and so on. As the moniker “city symphony” suggests, these films were often edited in such a way as to suggest a musical structure. Shots were treated like musical notes, sequences were organized as if they were chords or melodies, scenes were built up into movements or acts, and issues of rhythm, tempo, and polyphony figured prominently. But in all cases, the substance of these works was the city itself—or, rather, its cinematic representation—and the effect that was achieved was more poetic than expository in contrast to earlier scenics or travelogues that focused on touring urban landscapes. At the same time, most of these films combined their experimental nonfiction form with some basic elements of narrative. They eschewed the lives of individuals, focusing instead on the larger patterns that make up the urban fabric, but they frequently made use of a temporal structure to keep things from becoming overly abstract. Thus, we have films that focus on mornings and nights in the big city, alongside more typical dawn-till-dusk, dawn-till-late night, and dawn-till-dawn configurations, but virtually all of these films insist that they be understood as one- day-in-the-life of the city (or, in rare examples, cities) in question, regardless of how many weeks or months it might have taken to shoot them in the first place.

Throughout the 1920s, the characteristic elements of the city symphony were established and codified, to the extent that its unusual perspectives, skewed angles, rapid and rhythmic montage, special effects, and iconography became a kind of cinematic shorthand for modern metropolitan life, one that would appear in quite a number of fictional feature films in the 1930s and beyond. Among other features, the city symphonies focused on the spaces of the contemporary city and the inhabitants who populated them, creating the sense of a cross-section of the locations, activities, and social groupings that constitute modernity, and they tended to give the impression that these images represented “life as it is,” or “life caught unawares,” as in Vertov’s famous turn of phrase.2 Many of these city symphonies were key contributions to the emergence of the documentary film in the 1920s and 1930s, however they avoid “pure” or “absolute” nonfiction form, and instead combine narrative elements with an emphatically experimental form. In fact, they frequently feature the use of abstraction and defamiliarization techniques reminiscent of contemporaneous experiments in avant-garde painting and photography, and the highly fragmented, oftentimes kaleidoscopic sense of modern life that they present is organized through rhythmic and associative montage in such a way as to evoke musical structures.

The earliest examples of what can be called city symphony date from the early 1920s, when two key works were released. The first of these was Sheeler and Strand’s Manhatta, a ten-minute decisively modernist celebration of New York, which was conceived in 1919, shot in 1920, and received its theatrical premiere in 1921.3 The second was László Moholy-Nagy’s scenario A nagyváros dinamikája (Dynamic of the Metropolis, 1921–1922), a “Sketch of a Manuscript for a Film” whose urban-industrial iconography and attention to the “optical arrangement of tempo” would help codify the European city symphony in the years to come.4 First published in Hungarian in 1924, the screenplay was translated into German and combined with photographs and a modernist design in Moholy-Nagy’s 1925 Bauhaus book Malerei Photographie Film. Another important mid-1920s contribution to the phenomenon was Alberto Cavalcanti’s Rien que les heures (Nothing but Time, 1926), a film that is actually primarily a work of fictional narrative, but one that makes great use of its urban locations and attempts to show one day in the life of Paris’s down and out districts over the course of 45 minutes. Interestingly, in spite of its obvious fictional trappings, Rien que les heures was released at a time when filmmakers, scholars, and theorists were conceptualizing the documentary film for the first time, and, for some reason, the film was seen as one by many, and it has been connected to the city symphony phenomenon ever since. According to John Grierson, in Cavalcanti’s film, “Paris was cross- sectioned in its contrasts—ugliness and beauty, wealth and poverty, hopes and fears. For the first time the word ‘symphony’ was used, rather than story.”5 Of course, Cavalcanti would go on to become one of the leading figures of the British documentary movement of the 1930s, which may help to explain why colleagues of his, like Grierson and Paul Rotha, were so eager to position Rien que les heures as a documentary. In any case, one of the ironies of the time was that at roughly the same time that Cavalcanti was producing and releasing his film, Robert Flaherty, the father of the modern documentary film, made Twenty-four Dollar Island (1927), but somehow this film tended to get overlooked by the same scholars.

However, if these early texts were progenitors, it was Walter Ruttmann’s Berlin which fully established the genre, touched off the phenomenon, and whose subtitle, Die Sinfonie der Grosstadt, provided this movement with its nickname. And it was Berlin more than another film that first demonstrated how the everyday life of the city could be transformed into a modernist work of art. Berlin also caused a sensation. The cycle that it touched off reached its apex almost immediately, and 1929 saw the release of Vertov’s Man with a Movie Camera, Moholy-Nagy’s Impressionen vom alten Marseiller Hafen (Vieux Port) (Impressions of the Old Harbor of Marseille), Ivens and Franken’s Regen, Lucie Derain’s Harmonies de Paris (Harmonies of Paris), Corrado D’Errico’s Stramilano, Henri Storck’s Images d’Ostende (Images of Ostend), and Robert Florey’s Skyscraper Symphony, among others. By the late 1920s and early 1930s, the city symphony form had attracted the interest of a large number filmmakers whose names would become prominent in the history of cinema: Marcel Carné, Manoel de Oliveira, Alexandr Hackenschmied (a.k.a. Alexander Hammid), Lewis Jacobs, Boris Kaufman, Mikhail Kaufman, Georges Lacombe, Jay Leyda, Robert Siodmak, Edgar G. Ulmer, Herman Weinberg, and so on, in addition to the aforementioned Strand, Sheeler, Moholy-Nagy, Cavalcanti, Flaherty, Ruttmann, Vertov, Ivens, Florey, and Vigo. By the late 1930s, this group would also include such luminaries as Rudy Burckhardt, Ralph Steiner, and Willard Van Dyke. In addition to the cinematic explorations of Berlin, Moscow, Paris, and New York—the cities that inspired the most famous of these films—filmmakers also turned their “kino-eyes” on Nice, Marseille, Lourdes, Düsseldorf, Milan, Ostend, Porto, Prague, Rotterdam, Montreal, São Paulo, Liverpool, and many other places. In the late 1920s and early 1930s, many city symphonies were made and probably even more were planned but never realized. Alfred Hitchcock, for instance, flirted with the idea of making an experimental “film symphony” entitled London or Life of a City in collaboration with Walter Mycroft: “The story of a big city from dawn to the following dawn. I wanted to do it in terms of what lies behind the face of a city—what makes it thick—in other words, backstage of a city.”6

In the early 1930s, the city symphony cycle continued to expand and it simultaneously also became increasingly professionalized and commercialized as several municipal authorities commissioned films in the style of Ruttmann’s Berlin. Ruttmann’s own film can be understood on some level as a commissioned work, as it was produced as part of a quota program (”Kontingentfilm”) for Fox Europe. Other works, such as De Stad die nooit rust (The City that Never Rests, Andor von Barsy and Friedrich von Maydell, 1928), A Day in Liverpool (Anson Dyer, 1929), Praha v záři světel (Prague by Night, Svatopluk Innemann, 1928), Fukkõ Teito Shinfoni (Symphony of the Rebuilding of the Imperial Metropolis, anonymous, 1929), or Ruttmann’s Kleiner Film einer großen Stadt … der Stadt Düsseldorf am Rhein (Small Film for a Big City: The City of Düsseldorf on the Rhine, 1935), Stuttgart: die Großstadt zwischen Wald und Reben—die Stadt des Auslanddeutschtums (Stuttgart, the Big City Between Forest and Vines—The City of Germans Abroad, 1935), and Weltstrasse See, Welthafen Hamburg (The Ocean as World Route, Hamburg as World Port, 1938) were made for or in cooperation with commissioning agencies or municipalities and were not infrequently used for city promotional purposes or even propaganda. In other cases, such as Bonney Powell’s Manhattan Medley (1931), produced by Fox Movietone, or Gordon Sparling’s Rhapsody in Two Languages (1934), which deals with Montreal and was produced by the Canadian outfit Associated Screen News, we can see clear examples of the further commercialization of the city symphony film. However, the vast majority of city symphonies were independent productions or personal projects by artists, although some of these artists, like Vigo and Florey, were professionals working in the film business who made city symphonies as personal project on the side. In the September 1929 issue of Movie Makers, Marguerite Tazelaar captured this personal/professional split in a profile of Florey. Tazelaar writes that Florey, while working for big film studios, “spends his spare moments shooting experimental pictures with his small movie camera in the by-ways and highways of New York, Los Angeles, or where-ever he happens to be.” Inspired by Florey’s Skyscraper Symphony, Tazelaar concludes that “the city” is the perfect topic for amateur filmmakers interested in an “experimental approach.”7 This interest in avant-garde representations of the city was widespread in amateur film circles in the late 1920s and early 1930s, as for example Leslie P. Thatcher’s prize-winning city symphony Another Day (1934), Friedrich Kuplent’s Prater (1929), Lynn Riggs and James Hughes’s A Day in Santa Fe (1931), or Liu Na’ou’s Chi sheyingji de nanren (The Man Who Has a Camera, 1933) demonstrate. Harry Potamkin in his discussion of the “montage films” by Cavalcanti, Ruttmann, and Vertov, urged amateurs to film and critique everyday aspects of American life or people outside the private confines of the home.8 As Patricia Zimmermann noted, “It is significant that Potamkin cited examples of films about public places; these examples attacked the amateur movie magazine emphasis on private life and personal travel.”9

Many leading film critics and theorists of the period were inspired to write about these films, expressing intrigue, fascination, and, in some cases, consternation in response to this body of work. When he described the impact of Ruttmann’s Berlin, Grierson wrote,

No film has been more influential, more imitated. Symphonies of cities have been sprouting ever since, each with its crescendo of dawn and coming-awake and workers’ processions, its morning traffic and machinery, its lunchtime contrasts of rich and poor, its afternoon lull, its evening denouement in sky-sign and night club. The model makes for good, if highly formulaic, movies.10

Acknowledging the currency of “the symphonic form” or “symphony form” with aspiring filmmakers in particular, Grierson also noted, “Berlin still excites the mind of the young, and the symphony form is still their most popular persuasion.” To his dismay, he added that, out of 50 pitches that he, as a producer, might receive from his younger colleagues, “forty- five are symphonies of Edinburgh or of Ecclefechan or of Paris or of Prague.”11

Of course, Grierson was most likely exaggerating, but the fact of the matter is that the city symphony form was a much more significant development in the history of cinema than has generally been granted. Far from a mere footnote to film history limited to a handful of famous and semi-famous films, the city symphony inspired an international movement between the late 1920s and the late 1930s, one that encompassed four continents, dozens of cities, and well over 80 films. It is our conviction that the story of this phenomenon is a neglected chapter in the history of cinema. This book intends to help rectify this state of affairs by offering a comprehensive overview of this international cycle of films, many of which have fallen into oblivion and received limited or no scholarly attention since their release. True, not all of them have the encyclopedic span and ambitions of Ruttmann and Vertov’s films—indeed, several of the films discussed in this volume might be labeled as “city sinfoniettas” rather than richly orchestrated symphonies. Many of these films also differ stylistically from Berlin or Man with a Movie Camera, sometimes quite dramatically so, demonstrating that the city symphony phenomenon was much more complex and multi-layered than generally assumed.

As most of these films were primarily independent works that found screening possibilities outside the commercial cinema circuit, the proliferation of the city symphony phenomenon was largely made possible through the ciné-clubs and film societies that flourished in the second half of the 1920s and early 1930s.12 Moreover, these ciné-clubs were also meeting places where filmmakers were often invited to introduce their films or give lectures, contributing to an international network of film leagues and avant-garde ciné-circles. International meetings and events, such as the Werkbund exhibition Film und Foto in Stuttgart in 1929 and two editions of the Congrès International du Cinéma Indépendant (held in La Sarraz in Switzerland in 1929 and Brussels in 1930, respectively) also included screenings of city symphonies, and therefore further contributed to its currency.13 In many ways, the twists and turns in the exhibition history of Manhatta help to illuminate the peculiar status these short works of experimental nonfiction held in the 1920s. First screened amongst a small group of artist-friends in 1920, Manhatta received its public premiere in 1921 as a New York “scenic” on a variety bill under the title New York the Magnificent, before being screened as part of the Paris Dada group’s Soirée du coeur à barbe in July 1923 as Les Fumées de New York (The Smokes of New York). When it returned to New York, after having received this blessing from the Parisian avant-garde, it was understood differently, and it now carried the Whitmanesque title it has been known by ever since. Finally, in 1927, it played as part of the 18th London Film Society annual—again, under the title Manhatta—before disappearing soon afterwards, for not even Sheeler or Strand had a copy, apparently, only to reemerge in the archive of the British Film Institute in 1949.14 It was only then that Manhatta’s status and reputation began to be rehabilitated, and the film began to be recognized as a significant contribution to both experimental cinema and nonfiction filmmaking, eventually attaining some degree of canonicity. Lastly, the proliferation of city symphonies was also made possible extra-cinematically, through the circulation of film and art journals. Jay Leyda, for instance, was first inspired to make avant-garde films not by seeing them, for he grew up in Dayton, Ohio and had no access to such films at the time, but by reading about them in film and arts journals such as La Revue du cinéma, Der Querschnitt, Variétés, Theatre Arts Monthly, Hound & Horn, and Close Up, most to which he subscribed.15 Later, when he arrived in New York City to become Ralph Steiner’s darkroom assistant, he finally got the opportunity to see avant-garde films on screen and in earnest, and it was the “dazzling experience” of seeing Man with a Movie Camera at the Eighth Street Playhouse that provided the inspiration for him to make A Bronx Morning (1931).16

What is a city symphony precisely? What does it take for a film to be accurately called a city symphony? Simply put, a city symphony is an experimental documentary dealing with the energy, the patterning, the complexities, and the subtleties of a city. However, it is important to note that city symphonies originated at a time when the notion of the “documentary film” had not yet come into existence, and that “experimental” or “avant-garde” cinema was just coming into its own. In fact, several key city symphonies such as Berlin, Man with a Movie Camera, Regen, and À propos de Nice were instrumental when it came to shaping the directions taken by both documentary and experimental filmmakers. And while city symphonies largely avoided resorting to storylines and characters, and instead focused on glimpses and impressions of city life, they differed from earlier urban-focused scenics and travelogues in that they did employ some basic narrative elements—notably, a “day-in-the-life-of-a-city” structure—in order to organize and give life to the enormous number of shots and scenes captured by their cameras.

The case of Cavalcanti’s Rien que les heures is illuminating here. A fictional film with actors playing imaginary characters, this often poetic film deals primarily with everyday dramas on the streets and in the alleys of Paris, at the margins of society. At the time of its release, the film circulated widely in cine-club and film society circles, and it was discussed at length, but, as far as we can tell, no one discussed it as being a “symphony” or a “symphonic” film from the start. However, in the wake of the release of Ruttmann’s Berlin, things changed drastically. The term “symphony” was no longer limited to abstract experimental films like Viking Eggeling’s Symphonie diagonale (Diagonal Symphony, 1924)—it now became perfectly acceptable to use the moniker “symphony” to describe a particular kind of film whose approach was grounded in the representation of “physical reality.” By 1929, in the wake of Vertov’s Man with a Movie Camera and Ivens and Franken’s Regen, it was clear that a craze for such films was well underway, and critics and scholars scrambled to make sense of it. In an attempt to determine where this craze had come from and how it had gotten its start, they looked back to Cavalcanti’s Rien que les heures because of the clear parallels it offers to aspects of Berlin, Man with a Movie Camera, and other such films, and it became “the first of the ‘day in the life of a city’ cycle,” regardless of the fact that it had been preceded by Strand and Sheeler’s Manhatta and Moholy-Nagy’s typo-photo Dynamic of the Metropolis, and was released around the same time as Robert Flaherty’s Twenty-four Dollar Island. One can surmise why this might have happened. Manhatta and Twenty-four Dollar Island were both rather obscure American films—although Manhatta was shown in Paris and London in the 1920s, and Twenty-four Dollar Island was made by the single most important documentarian of his day—and Dynamic of the Metropolis was not a film. What is harder to understand is why early critics and theorists such as John Grierson, Paul Rotha, Siegfried Kracauer, and others, were so insistent that Rien que les heures was a documentary, when it is quite clear that it is primarily a work of fiction, one that features long segments that are entirely theatrical in nature, and one that has relatively little documentary value. These same critics and scholars refrained from labeling Dimitri Kirsanoff’s Ménilmontant (1926) a documentary or a city symphony, and with good reason, but it was released the very same year as Rien que les heures, its similarly melodramatic action takes place in the same kind of down-and-out Parisian milieu, and it features a similar interest in using unusual compositions and quick editing in order to simulate the pace and energy of modern Paris. Eugène Deslaw’s La Marche des machines (The March of the Machines, 1927) is often grouped together with the “symphonic” films, but it is his Montparnasse from 1930 that is more pertinent here, for it shares a similar interest in la bohème and in the Parisian quartiers as these other two films, it, too, is a showcase for audacious cinematography and montage, and it also contains many colorful characters, but it doesn’t contain any actors or any story lines, and no one would confuse it with either of these earlier films.

Harry Alan Potamkin was one of the few critics active in the 1920s and 1930s who was clear about the distinctions between Rien que les heures and films like Berlin and Man with a Movie Camera. He, too, grouped these three films together, but he did so in the context of “The Montage Film” and not according to that of the city symphony, and he was adamant that even though they shared some commonalities, the nature of these films was entirely different.17 “There is no motif that tells a story [in Berlin] as in Only the Hours,” he wrote. “Not individual human episodes but the City is the pattern. Only the Hours is romance; Berlin is document. Only the Hours is subjective; Berlin is objective”18 When it came to Vertov’s Man with a Movie Camera, Potamkin argued that it had taken a similar approach to Berlin, but had expanded upon it greatly. Here, he wrote, Vertov,

has produced, upon the objective principle of Berlin, a film of amazing fluidity with successive images which do not always connect directly with each other. He has, in the typical Russian way, sought to make the images symbolic of the land and has endeavored to include in the film all the various contrasts of the city’s life, of human existence—work and pleasure, birth and death.19

The city symphonies of the 1920s and 1930s may contain some basic narrative events—like a dawn-to-dusk structure, for instance—but, for the most part, they are not story films, and similarly, for the most part, they are not romances. Rien que les heures is narratively organized around the encounters of a streetwalker, a woman selling newspapers, a sailor, a landlady, a shopkeeper, and a thug, and the highly allegorical image of an old woman stumbling and crawling down Parisian back alleys before appearing to succumb to fatigue. Like Cavalcanti’s Rien que les heures, Robert Siodmak, Edgar Ulmer, and Billy Wilder’s Menschen am Sonntag (People on Sunday, 1930) has frequently been cited as being a canonical example of the city symphony, but it, too, features actors and scripted drama, and while the film benefits from a convincing and wide-ranging sense of “documentary truth,” it would be a stretch to characterize it as a work of nonfiction. Menschen am Sonntag is subtitled “a film without actors,” but this is simply because the interpreters were non-professionals whose day jobs were those that they portrayed in the film. Thus, although Menschen am Sonntag is closely connected to the city symphonies genre, it also prefigures Neorealism in certain ways.20 Yet another film combining the city symphony formula with a sparse character-based narrative is Herman G. Weinberg’s Autumn Fire (1933), which depicts an encounter between a man living in New York and a woman living in the countryside, eventually leading to a climactic reunion in the city. As a result, the city in this film acts as “an externalization of character and emotion, metaphorically contrasting the city (man) with nature (woman).”21 Some other city symphonies have characters, too, but often these characters function more in a symbolic manner than as nuanced, psychologically convincing individuals. In Vertov’s Man with a Movie Camera, the titular character is in some ways an allegorical figure who looms over the city and the revolutionary society that created it. This cameraman, played by Mikhail Kaufman, Vertov’s brother and the film’s actual principal cinematographer, is also a perfect demonstration of the avant-garde’s fascination with reflexivity, for he, along with Elizaveta Svilova, the film’s editor, act as stand-ins for Vertov himself, playfully intervening in his very own artwork. Likewise, in Alexandr Hackenschmied’s Bezúčelná Procházka (Aimless Walk, 1930), we see the city through the eyes of a vaguely sketched figure strolling through the urban landscape. And in Footnote to Fact (Lewis Jacobs, 1933), it is a troubled woman sitting in her apartment, whose subjective thoughts and memories give us an impression of New York street life during the Great Depression. In these three examples, however, the characters are mere sketches—they may help to provide some sense of direction, but the films reject psychologism. Most city symphonies, however, are not character-based, and it is the city’s architecture, its technology and machinery, and the collective body of its anonymous population that are the true protagonists of these films. In so doing, these films broke from the narrative trajectory that Robert Flaherty’s Nanook of the North (1921) had mapped out, and which films such as Rien que les heures and Menschen am Sonntag had followed to a certain extent. Strikingly, Flaherty’s New York city symphony Twenty-four Dollar Island is his only documentary that doesn’t include individualized characters.

René Clair’s Paris qui dort (The Crazy Ray, 1924), which had an enormous influence on Vertov and his conceptualization of Man with a Movie Camera, has also been mentioned in relation to the city symphony.22 Although Paris is certainly more than a mere backdrop in this film and although some scenes contain some of the visual effects used in several city symphonies, there is no question that Paris qui dort falls outside the limits of the genre due to the importance of its narrative development and its use of fanciful characters and professional actors. In the late 1920s, Clair also made another film that shares similarities with city symphonies: La Tour (The Eiffel Tower, 1928), which deals with the Eiffel tower, a key emblem of urban modernity and also a construction closely linked to the development of the new visual languages of Cubism, Constructivism, and the New Vision. Although the city of Paris appears in a few shots, this film is first and foremost a study of the tower unlike some similar films that give more attention to the relation between a building and its urban environment such as De Brug (The Bridge, Joris Ivens, 1928), Les Halles (The Central Market, Boris Kaufman and André Galitzine, 1927/1929), Así nació el obelisco (This Is How the Obelisk Was Born, Horacio Coppola, 1936), and De Maasbruggen (Bridges over the River Meuse, Paul Schuitema, 1937)—all films in which the building is also used as an optical device offering new and surprising vistas on the city.

Combining experimental documentary with elements from narrative cinema and sharing similarities with “absolute” films and “machine films,” the cycle of city symphonies is not easy to demarcate. This might explain why scholars often use generic terms in reference to the city symphony films, but never go as far as to state outright that this group of films constitutes a genre. Thus, John Grierson wrote of a “symphony approach” that had been initiated by Cavalcanti and expanded upon and popularized by Ruttmann.23 Likewise, Paul Rotha claimed that Cavalcanti and Ruttmann developed the “day in the life of a city cycle.”24 Siegfried Kracauer mentioned a “series of city symphonies” in the pages of Theory of Film, lumping these films under an avant-garde interest in “physical reality,” whereas in his earlier work, From Caligari to Hitler, he had discussed these films as a subcategory of the “montage film.”25 More recently, authors such as Annette Michelson, William Uricchio, Edward Dimendberg, Helmut Weihsmann, and Jan-Christopher Horak, among others have grouped and described many of the “city films” discussed in this volume—however, without explicitly labeling or defining them as a genre.26

We would like to make the case that the city symphonies phenomenon of the interwar years amounts to a full-fledged genre—not the strongest or most stable of genres, perhaps, but a full-fledged genre nonetheless, and one that exerted a powerful influence well outside its specific contours in its prime, and has continued to exert considerable influence decades later. Why the uncertainty? So much of the confusion comes from the fact that genre criticism was still in its infancy, and genre theory was years off from being formulated, at the time that the city symphonies phenomenon was at its peak. As mentioned earlier, experimental and avant-garde cinema had only really come into its own in the immediate aftermath of World War I. While the nonfiction film had existed since the very beginnings of cinema, the documentary film only began to be conceived in the 1920s, the term “documentary” as it applies to film was only coined in 1926 (by John Grierson), and the form was only beginning to be theorized by the likes of Grierson and others in the early to mid-1930s, although, clearly, Vertov had been doing so for quite some time in the Soviet Union in his own peculiar way. Similarly, the self-consciously modernist art film was also a creation of the post-World War I era, including “absolute cinema” and “cinéma pur.” In other words, there was a considerable amount of flux at precisely the time when the city symphony was taking shape. Combining elements from experimental, documentary, and narrative film, the city symphony form embodied this flux, and the ensuing phenomenon erupted so quickly and so powerfully, even those commentators who were aware of such trends were nevertheless caught off guard and generally had a hard time taking stock of what was taking place before their eyes.

Rick Altman’s “semantic/syntactic approach to film genre,” which he first published in the early 1980s, but which formed the foundation for his later Film/Genre (1999), is one that can help us to make a case for the city symphony as genre. As Altman explained, genre criticism in film studies continued to be marked by uncertainty and hesitation well into the 1980s.27 Issues of inclusivity versus exclusivity, of reconciling genre theory and genre history, and of whether to favor semantic approaches to genre or syntactic ones, were among those that continued to bewilder critics and scholars and had led to a body of work on film genres that was riddled with contradictions and mischaracterizations. Altman argued that the key was to combine the semantic approach with the syntactic approach, that these two approaches were complementary, that they could be easily reconciled, and that they provided a supple and probing model for the analysis of film genre.28 Doing just that, combining a semantic analysis of the city symphonies phenomenon with a syntactic one, not only helps to clarify this body of work as a genre, it can help us to be more precise about the genre’s development, its specificities, and its limits. The following paragraphs discuss the important themes and motifs that characterize the semantics of the city symphony. Next, we will focus on the structural, stylistic, and formal devices that constitute the syntax of these films, which show similarities with contemporaneous trends in painting and photography. As in any other genre analysis, these characteristics—both semantic and syntactic—are not meant to be used as a checklist, but virtually all of the 80+ city symphonies we’ve identified (see Part Three) meet most, if not all, of these criteria. In addition, we will demonstrate that, in the case of the city symphony, form and content (or syntax and semantics) go perfectly hand in hand. The city symphony is not only a film about the modern metropolis; its formal and structural organization is also the perfect embodiment of metropolitan modernity.

In contrast with earlier city vignettes, scenics, or travelogues, city symphonies are rarely interested in historical monuments and tourist sites that constitute the “official” face of the city. In their attempt to make a panoramic view of a city, some films, such as Cavalcanti’s Rien que les heures, Corrado D’Errico’s Stramilano, André Sauvage’s Études sur Paris (Studies on Paris, 1928), Ubaldo Magnaghi's Mediolanum (1933), Otokar Vávra’s Žijeme V Praze (We Live in Prague, 1934), Jean Lods’s Odessa (1935), or Ruttmann’s films on Düsseldorf and Stuttgart may contain shots of historical landmarks, but they tend to present these monuments as part of the everyday life of the city, integrated into the mundane spaces of the modern metropolis. A few other city symphonies focus on “new” monuments, which acquired fame as masterpieces of modern engineering, such as the mobile iron bridges featured in De Brug, Impressionen vom alten Marseiller Hafen (Vieux port), and De Maasbruggen. Favoring contemporary cityscapes with modern buildings and advanced infrastructure, city symphonies are usually about “new cities,” cities that had only existed for a relatively short period of time, like Chicago, or cities such as New York, Berlin, Moscow, Milan, or Rotterdam, which underwent a process of rapid growth and radical modernization that wholly transformed them in a very short period of time. In the 1920s and 1930s, there were no city symphonies that dealt with places such as Florence, Venice, or Bruges, the image of which relied heavily on their preserved historical heritage—although José Val del Omar’s Vibracion de Granada (Vibrations of Granada, 1935) might be an exception. Some city symphonies do indeed deal with places that have a long past and a rich architectural heritage—such as Paris and Amsterdam—but they usually choose to present the metropolis as the locus of modernity. Consequently, the emblems of urban modernity—industry, large buildings, crowds, motorized traffic, billboards—not only abound in city symphonies, they are quite specifically foregrounded.

City symphonies often present the viewer not only with the modern metropolis, but with a vision of the modern megalopolis. Many of the featured cities are large cities that are nevertheless rapidly enlarging because of the effects of the forces of industrialization and modernization. Strand and Sheeler’s Manhatta, Robert Flaherty’ Twenty-four Dollar Island, Ruttmann’s Berlin, and Adalberto Kemeny and Rudolpho Rex Lustig’s São Paulo: A Symphonia da Metrópole (São Paulo: A Symphony of the Metropolis, 1929) literally show the city being built, the city in the process of expanding, by drawing attention to impressive construction sites. In the films dedicated to New York and Chicago, these are construction sites with grids of steel girders of impressive skyscrapers, not only a prominent icon of urban modernity, and one that was a source of great fascination for both American and European modernists, but also a structure perfectly suited for the dramatic alternation of impressive high-angle and low-angle views favored by the vanguard photographers and filmmakers of the era.29 As its title indicates, Robert Florey’s Skyscraper Symphony focuses entirely on the impressive high-rise structures that, already in the late 1920s, had become a universal symbol of metropolitan growth, technological progress, and capitalist development. Strikingly, even though Berlin had no skyscrapers at the time, aside from its recently completed radio tower, when it came to creating the posters and advertising materials for Berlin, Ruttmann used photomontages to do so, and he populated these images with New York skyscrapers, providing a particularly odd but notable example of the so-called “Americanism” of the European avant-garde.30 Apart from skyscrapers, all kinds of other high-rise structures, such as steel towers, bridges, and factory chimneys figure prominently in city symphonies. High-angle shots from tall structures as well as low-angle shots representing them are staples of these films, revealing a profound interest in the new vertical city, as opposed to the traditional horizontal city of the past. Thus, the Berlin Funkturm, which was completed in 1926, features in Berlin’s finale, whereas Man with a Movie Camera uses the dizzying heights of factory chimneys, bridges, and towers to evoke the energy and drive of the bustling metropolis and of a Soviet society that was rapidly modernizing and industrializing.

City symphonies also emphasize the drive and energy of the metropolis by referring to its industry, acknowledging the process of industrialization as the main factor of urbanization. A large majority of city symphonies focus on “industrial cities” such as Paris, Berlin, Liverpool, New York, Chicago, Milan, or Rotterdam, extensively documenting their factories and the urban labor force. Factory buildings, gates, and chimneys are recurring topoi in city symphonies, as well as a wide variety of machines and their components, such as wheels, bolts, and pistons. Memorable shots illustrate the use and manipulation of machines—a topic that reaches its peak in Vertov’s Constructivist aesthetic, which intertwines the manual and the mechanical, suggesting an almost organic bond between man and machine. Through editing, entire sequences in Ruttmann’s Berlin, Vertov’s Man with a Movie Camera, Mikhail Kaufman and Ilya Kopalin’s Moskva (Moscow, 1926), Dyer’s A Day in Liverpool, and D’Errico’s Stramilano are marked by the rhythm of machines. Ivens’s De Brug, which focuses on a mobile bridge in the Rotterdam harbor as a node in the urban network, even shows a strong resemblance to what the critic Harry Potamkin in 1929 called “machine films,” such as Deslaw’s La Marche des machines or Mechanical Principles (Ralph Steiner, 1930).31 De Brug as well as Schuitema’s De Maasbruggen and Moholy-Nagy’ Impressionen vom alten Marseiller Hafen also illustrate the city symphony’s interest in harbors as a key locus of industrial activity in the modern metropolis. Indeed, a number of these films, such as Manhatta, Twenty-four Dollar Island, De stad die nooit rust, A Day in Liverpool, and Douro, faina fluvial (Labor on the Douro River, Manoel de Oliveira, 1931), depict the rhythm of passing ships, boats, and ocean liners, the nervous activity on the quays, the muscular labor of dock workers, and the mechanical ballet of impressive cranes and conveyor belts.

Apart from depicting an industrial landscape of factories, chimneys, steel mills, silos, furnaces, and power stations, many city symphonies also emphasize that, in the words of Siegfried Giedion, “mechanization has taken command” of the lives of urbanites, depicting the invasion of modern technology into the everyday as illustrated by the prolific shots of printing presses, radio towers, dishwashers, elevators, and electric lamps. In addition, the city is unmistakably presented as a locus of labor in all its possible class manifestations, from street sweepers clearing dirt and debris to white-collar workers in state-of-the-art office spaces equipped with typewriters, telephones, and ticker-tape machines. An icon of modern telecommunication, the telephone switchboard is a popular motif in city symphonies and key films by Ruttmann and Vertov, as well as the films on Moscow and Liverpool by Kaufman, Kopalin, and Dyer respectively, also include striking shots of telephone operators, who are presented as unsung heroines of modernity, frantically working to keep communication channels flowing, against all odds.

A similar role is played by the traffic policeman, whose hands almost magically direct the movements and tempos of the city in Ruttmann’s Berlin, Vertov’s Man with a Movie Camera, Dyer’s A Day in Liverpool, Derain’s Harmonies de Paris, and Kemeny and Lustig’s São Paulo. Motorized traffic, of course, is another prominent symbol of urban modernity. In fact, the sheer movement of the chrome and metal surfaces of automobiles, streetcars, and trains alone is sometimes enough to create an impressive visual spectacle, as indicated by Henri Chomette’s Jeux des reflets et de la vitesse (Play with Reflections and Speed, 1925), which illustrates perfectly the French avant-garde’s interest in the “pure cinema” of optical phenomena. A similarly impressionistic approach can be found in Ivens’s modest Études des movement à Paris (Movement Studies in Paris, 1927), in which the filmmaker simply directs his jerky camera at cars speeding on the Paris boulevards, or in Alex Strasser’s Impressionen der Großstadt, a.k.a. Berlin von unten (Impressions of the Metropolis, a.k.a. Berlin from below, 1929), which is largely made of low-angle shots of hurrying feet, car tires, and traffic movement from “below” at several places in Berlin. Another striking image of traffic featured in many city symphonies is that of the elevated railways, which are especially apparent in films dedicated to New York and Chicago, such as Manhatta, Skyscraper Symphony, Manhattan Medley, Seeing the World: Part One, A Visit to New York, N.Y. (Rudy Burckhardt, 1937), and Weltstadt in Flegeljahren: Ein Bericht über Chicago (World City in Its Teens: A Report on Chicago, Heinrich Hauser, 1931), but such railways are also a key aspect of Berlin. Such imagery evokes the idea of floating streets and multi-layered cities celebrated by many utopian urban planners of the era, such as Antonio Sant’Elia, Raymond Hood, and Le Corbusier. The impact of motorized traffic is often emphasized through its juxtaposition with older means of transport. In Ruttmann’s Berlin, Vertov’s Man with a Movie Camera, and Oliveira’s Douro: faina fluvial, cars are confronted with a horse and carriage or some other beast of burden pulling loads of goods. As its title indicates, Mit der Pferdedroschke durch Berlin (With the Horse-Drawn Carriage Through Berlin, Carl Froelich, 1929) explores the German capital from the perspective of a horse-drawn carriage.

Not surprisingly, given developments in the realms of retail, marketing, and advertising, most of the city symphonies also present the metropolis as a powerful locus of consumption. Factories mass-produce consumer items, people observe and purchase commodities of all kinds, fashion models parade around in haute couture, streets are lined with shops, meals and drinks are consumed, and the traffic in bodies and vehicles that figures so prominently in so many of these films attests to the commercial dynamism of these cities. Frequently, the camera draws attention to the spectacle of shop windows and the act of window shopping—and, indeed, window display mannequins are a striking presence in Ruttmann’s Berlin and Leyda’s A Bronx Morning, both of which recall the photographs of Eugène Atget, whose work had just recently been rediscovered by the Surrealists. Films such as Berlin, Sauvage’s Études sur Paris, and Conrad Friberg’s Halsted Street (1934) are among those that deal with the proliferation of advertisement through posters, billboards, columns, and outdoor electric advertising—evoking a forest of signs that parallels and illustrates Kracauer’s notion of the “surface culture” of modern urban commercial experience.32

The image of the city as a realm of commodity fetishism is also emphasized by presenting the city as a place of leisure and entertainment. Some films, such as Marcel Carné’s Nogent: El Dorado du dimanche (Nogent: Sunday El Dorado, 1929), Vigo’s À propos de Nice, and Storck’s Images d’Ostende deal entirely with holiday or weekend destinations. However, Vigo and Storck create a rather bleak image of Nice and Ostend, respectively: Vigo combines his exploration of the upper-class beach resort with social criticism and Storck visits Ostend on a windy winter day, focusing on disconsolate images of the fishing port and the waves of the sea. What distinguishes Vigo’s film from Storck’s is his fascination with the working-class culture of le Vieux Nice, as well as the Surrealist pleasures of its Carnival. Many other city symphonies show urbanites visiting bars and restaurants; going to a concert or a zoo; and watching soccer games, boxing matches, horse races, and many other sporting events. Cavalcanti’s Rien que les heures, Ruttmann’s Berlin, Vertov’s Man with a Movie Camera, Carné’s Nogent, László Moholy-Nagy’s Grossstadt- Zigeuner (Gypsies of the Metropolis, 1932), Powell’s Manhattan Medley, and Sparling’s Rhapsody in Two Languages feature footage of people dancing, and chorus lines and other extravagant displays also appear regularly. In addition, musicians abound in city symphonies, a characteristic that underlines the rhythms and musical structures that are so crucial to the genre. Often these scenes take place in night clubs and concert halls, but in some cases, such as Moholy-Nagy’s Grossstadt-Zigeuner and Pierement (Barrel Organ, Jan Teunissen, 1931), for instance, we find a focus on street musicians.

Last but not least, city symphonies also deal reflexively with cinema spectatorship and the experience of cinema from time to time, with Symphony of the Rebuilding of the Imperial Metropolis and Berlin being two notable examples. Famously, of course, Vertov’s Man with a Movie Camera develops this topic into one of the central elements of the film, contributing to its highly self-reflexive approach. Cinema-going is also a form of nocturnal entertainment—a topic often neglected in city films of the 1920s and 1930s due to technical limitations. Nonetheless, some city symphonies such as Berlin, Les Nuits électriques (Electric Nights, Eugène Deslaw, 1929), Rhapsody in Two Languages, Prague by Night, City of Contrasts (Irving Browning, 1931), and Manhattan Medley helped pioneer the cinematic depiction of urban nightlife and electrical illumination, and are consistent with the fascination with electricity and electrification that had been such an important part of industrialization and urbanization in North American since the 1880s, and that swept Europe in the 1920s. Indeed, electrification and the restructuring of the urban night were key aspects of late nineteenth- and early twentieth-century modernity, as critics such as Walter Benjamin and Siegfried Kracauer pointed out, they were closely linked to both the rationalization of urban life, as well as to its reenchantment.33

Another important city symphony motif that symbolizes the energy and vibrancy of the modern metropolis is the crowd. By means of panoramic shots as well as a camera that plunges into the flow of pedestrians in the streets, city symphonies depict streets, boulevards, and squares filled with people. These may consist of parades, religious processions, or specific festivities—such as the pilgrims in Charles Dekeukeleire’s Visions de Lourdes (Visions of Lourdes, 1932) or the carnival in the films on Nice and Düsseldorf by Vigo and Ruttmann respectively—but usually crowds are presented as a component of the everyday life in the modern metropolis, such as the masses of commuters in Manhatta, De Maasbruggen, and Nogent. Representing “the people” rather than “the mob,” crowds in city symphonies are not presented as dangerous and menacing organisms as they often were in late nineteenth-century crowd theory such as in Gustave Le Bon’s highly influential La Psychologie des foules (1895).34 City symphonies, first and foremost, cherish crowds as a cinematic spectacle, a kinetic and phantasmagoric swarm of shapes and colors. Instead of a threatening force moving in a single direction, crowds are instead represented as heterogeneous, atomized, and chaotic, emphasizing the kaleidoscopic qualities of metropolitan life. As a result, aside from the openly and explicitly revolutionary aesthetics of Vertov’s Man with a Movie Camera, city symphonies only focus on the potential for action or revolution that crowds seem to promise in passing, if at all. Furthermore, most city symphonies also acknowledge that the modern crowd is a highly diverse entity, made up not only of proletarian masses, but also of other social classes and groups. This is an issue of great importance, as the urban crowd is one of the city symphony’s key motifs.

Although many city symphonies embrace the streets and boulevards filled with swarms of people, others show us deserted streets evoking urban loneliness and alienation.35 Reminiscent of the paintings by Giorgio De Chirico, Edward Hopper, or Paul Delvaux, films such as Rien que les heures, Regen, Images d’Ostende, Berliner Stilleben (Berlin Still Life, László Moholy- Nagy, 1932), Gamla Stan (Old Town, Stig Almqvist, Erik Asklund, Eyvind Johnson, and Artur Lundkvist, 1931), Autumn Fire, Paris express ou Souvenirs de Paris (Paris Express or Souvenirs of Paris, Marcel Duhamel and Pierre Prévert, 1928), and Études sur Paris, depict lonely, isolated, and contemplative figures in the modern metropolis, which, in this formulation, is presented as an uncanny or melancholic landscape. Instead of the hectic masses of people and the rhythms of motorized traffic that Ruttmann or Vertov loved to shoot, these films focus on the hidden streets, mysterious voids, and desolate suburban regions that can also be found in the works by many photographers associated with the Surrealist movement such as Eugène Atget, Brassaï, Marcel Lefrancq, Jacques-André Boiffard, and Eli Lotar.36 Often, these films show solitary roaming figures reminiscent of the twentieth-century flâneurs one finds in Surrealist novels, characters who delve into the maze of the city streets, a field of action that becomes the stage for surprising encounters and revelations of all kinds. Alexandr Hackenschmied’s Aimless Walk is entirely structured around the drift of a young man across the landscape of Prague, travelling from the city center to its outskirts on foot and by tram. In this particular group of films, there is also a striking interest in an urban landscape that is difficult to define, a terrain vague or wasteland around the edges of the city, such as the desolate port in Storck’s Images d’Ostende, the outskirts of Berlin in Moholy-Nagy’s Grossstadt-Zigeuner, and the Paris suburbs in Sauvage’s Études sur Paris. In fact, the heterotopic space of the banlieue is the main topic of Georges Lacombe’s La Zone: Au pays des chiffonniers (The Zone: In the Land of the Rag-Pickers, 1928), which portrays the daily life of rag-pickers living in the periphery of Paris much as Atget had in his photographic documents in earlier years. Strikingly, the cinematic exploration of these peripheral zones as well as of popular neighborhoods often contain images evoking some sort of pre-modern city life. Footage of children in films such as Ruttmann’s Berlin, Sauvage’s Études sur Paris, Moholy-Nagy’s Berliner Stilleben, Leyda’s A Bronx Morning, and Jan Koelinga’s De Steeg (The Alley, 1932) indicate that the city is not only a place of industry and commerce but also a place where people live, and the streets are more than just transportation arteries, they are inhabited. Along similar lines, many city symphonies also draw attention to stereotypical characters, such as street musicians, beggars, fortune tellers, and gypsies, again reaching back to the tradition of the nineteenth-century “urban picturesque.”

Interwar city symphonies not only share common themes and motifs, they are also characterized by a similar syntax and structural organization. First and foremost, these films are avant-garde documentaries on modern urban life. Eschewing stories and story lines and avoiding the use of hired actors, they are primarily works of nonfiction, tending to focus on “life caught unawares.” Furthermore, although some examples, including Visages de Paris (Faces of Paris, René Moreau, 1928), São Paulo, Lisbôa: Cronica anedótica (Lisbon: Anecdotal Chronicle, José Leitão de Barros, 1930), Esencia de Verbena (Essence of Verbena, Ernesto Giménez Caballero, 1930), Shankhaiskii Dokument (Shanghai Document, Yakov Bliokh, 1928), and Beograd Prestonica Kraljevine Jugoslavije (Belgrade: Capital of the Kingdom of Yugoslavia, Vojin Djordjevic, 1932), contain expository sequences, city symphonies generally avoid the expository mode of representation in favor of the poetic, and occasionally the reflexive.37 Of course, many of these films present generalities about the nature of life in the modern metropolis, and as the cycle became more commercial and less avant-garde in its orientation this tendency may have become more commonplace, but what’s often overlooked is the extent to which these films identify and examine the specifics of particular cities, neighborhoods, structures (and the areas that surround them), and events. Even Vertov’s Man with a Movie Camera, which famously combines images of Moscow, Kiev, and Odessa into a composite of modern metropolitan culture in the Soviet Union, is notable for its treatment of very specific and profoundly meaningful structures and spaces in each of the cities depicted, such as Moscow’s Tverskaya Street, Revolution Square, and, most notoriously, the Bolshoi Theatre, which, as Yuri Tsivian has argued, was subjected to “symbolic destruction” precisely because its meaning was so hotly contested in the Soviet Union in the 1920s.38 Other films evoke the specificities of a particular neighborhood (Impressionen vom alten Marseiller Hafen, A Bronx Morning, Montparnasse, Gamla Stan), a particular street or square (Jean Lods’s 1929 short Champs-Élysées, Halsted Street, Andor von Barsy’s Hoogstraat from 1929, De Steeg, Prater, Wilfried Basse’s 1929 Markt in Berlin), or even an area surrounding a particular building, as in (Les Halles, De Brug, De Maasbruggen, Así Nació El Obelisco, Budapest Fürdöváros (Budapest: City of Baths, István Somkúti, 1935), Ritmi di stazione (Railway Station Rhythms, Corrado D’Errico, 1933), Na Pražském hradě (Prague Castle, Alexandr Hackenschmied, 1931).

By presenting themselves as nonfiction films, city symphonies use location footage extensively and position themselves in opposition to those cityscapes, many of them enormously impressive, that were created in the film studio or on studio backlots in the 1920s and 1930s. Key works of Weimar cinema such as Die Strasse (The Street, Karl Grune, 1923), Der letzte Mann (The Last Laugh, Friedrich Wilhelm Murnau, 1924), Metropolis (Fritz Lang, 1927), and Asphalt (Joe May, 1929), as well as famous Hollywood productions, such as Sunrise (Friedrich Wilhelm Murnau, 1927), Just Imagine (David Butler, 1930), Street Scene (King Vidor, 1931), 42nd Street (Lloyd Bacon, 1933), and Gold Diggers of 1935 (Busby Berkeley, 1935), evoke the pleasures and dangers of the modern metropolis thanks to impressive production design and special effects.39 Despite often dealing with themes that are similar as the ones tackled in these feature films, city symphonies are marked by an explicit preference for filming in the street and for submerging into the hustle and bustle of real city life. Although several city symphonies such as Ruttmann’s Berlin, Vertov’s Man with a Movie Camera, or Vigo’s À propos de Nice include staged events that are absolutely unmistakable, this was hardly atypical within documentary filmmaking up until the rise of direct cinema and cinéma vérité in the 1960s. For the most part, however, city symphonies avoid the controlled conditions of the studio and instead seek the charge that comes from the camera’s confrontation with the unexpected and unpredictable contingencies of urban modernity.

Daring to create some kind of comprehensive sense of the modern city, the filmmakers who turned to making such films faced some obvious challenges. How does one create an encyclopedic sense of the city? Where does one begin? How does one organize and present this material? And just how much material is needed? What are the essential components necessary to capture the energy and dynamism of the modern metropolis? The most common device utilized by these directors was a “one-day-in-the-life-of-a-city” structure, one that simulated a chronological order—generally either a dawn-to-dusk or dawn-to-dawn narrative—but that was never actually shot in a single day.

Such narratives often result in a series of sequences focusing on the patterns by which the city comes to life in the morning, the importance of labor, and finally all kinds of recreation. Apart from the most famous examples—Berlin and Man with a Movie Camera—we can also find similar structures in films such as Manhatta, Rien que les heures, Moscow, La Zone, São Paulo, Stramilano, Manhattan Medley, City of Contrasts, Jean Lods and Boris Kaufman’s Vingt-quatre heures en trente minutes (Twenty-four Hours in Thirty Minutes, 1929), the Fox Movietone production of London Medley (1933), Sparling’s Rhapsody in Two Languages and City of Towers (1935), and others, most of which have the effect of suggesting a temporal organization of the workday as a mainspring of the urban capitalist economy. Emphasizing the importance of rationalized time for modern metropolitan life, films such as Ruttmann’s Berlin, Vertov’s Man with a Movie Camera, Kemeny and Lustig’s São Paulo, and Sparling’s Rhapsody in Two Languages prominently feature shots of clocks. In fact, in Cavalcanti’s Rien que les heures, the passing of time is, as the film’s title indicates, the central theme of the film.

Often combined with the dawn-to-dusk structure is the attempt to present the city as a living organism that works and rests, expends energy and then replenishes, sleeps and then awakens. Many city symphonies start with images of the awakening of the city—in Man with a Movie Camera, the opening of windows is literally juxtaposed to the opening of eyes of a woman getting out of bed, as well as to the lens of a motion picture camera being opened and closed, suggesting the awakening of the city, its inhabitants, and of the kino-eye aesthetic. In addition, machines, institutions, shops, and restaurants gradually come to life. Another key moment in the temporal organization of city symphonies is the motif of the arrival into the city, often featuring some form of modern transportation: the ferry transporting commuters in Manhatta, or the trains and trams bringing people to the city centers in Berlin, Man with a Movie Camera, Stramilano, Visions de Lourdes, A Bronx Morning, City of Contrasts, Rhapsody in Two Languages, and City of Towers. Like the scenes evoking awakenings, these scenes of transport also postpone and ritualize the film viewer’s approach to the city. In À propos de Nice, Jean Vigo stages the entering into the Mediterranean city by means of a toy train carrying tourists. Weltstadt in Flegeljahren includes a particularly elaborate introduction scene on a paddlewheel boat travelling the Mississippi, before crossing the state of Illinois in order to focus on Chicago.

Apart from the dawn-to-dusk structure, city symphonies also often present themselves as cinematic cross-sections of a certain city—the metaphor was famously used by Siegfried Kracauer in one of the earliest attempts to discuss a series of films showing similarities: Rien que les heures, Berlin, Man with a Movie Camera, Markt in Berlin, and Menschen am Sonntag.40 Indeed, it was through the use of the cross-section montage approach that these films attempted to create a sense of the city in its entirety. In a film such as Friberg’s Halsted Street, this cross-section structure is used almost literally: Halsted Street is an axis crossing the city of Chicago, cutting through both its poor and working-class districts, as well as its more affluent neighborhoods. Attempting to create a cross-section of the spaces and communities of the metropolis, city symphonies often highlight the contrasts and the diversity of the city. In fact, the “city of contrasts” trope—which provides the title for Irving Browning’s 1931 city symphony—is often used in order to display a series of stark juxtapositions: old versus new, light versus dark, rich versus poor, blue-collar versus white-collar, religious versus secular, traditional versus modern, et cetera. Not infrequently, these contrasts enable filmmakers to critique social conditions. Rather than simply describing and documenting a space, filmmakers such as Ruttmann, Vertov, Vigo, Moholy-Nagy, Hauser, and Friberg also create a sense of the socio-economic make-up of the subjects of their city symphonies by drawing attention to labor and housing conditions—topics that a number of notable social documentaries of the 1930s, such as Housing Problems (Arthur Elton and E.H. Anstey, 1935), Les Maisons de la misère (Houses of Misery, Henri Storck, 1937), and The City (Ralph Steiner and Willard Van Dyke, 1939), would eventually address in greater depth.

These contrasts are first and foremost visualized through editing, and especially through the use of sophisticated montage, and Kracauer was among those who noted the contributions of city symphonies and other cross-section films to the development of cinematic montage, and who credited “the Russians” with having provided the inspiration for Ruttmann’s Berlin.41 Rejecting simple causal relations and linear narrative, many city symphonies became the testing ground for Soviet montage practices inspired by Eisenstein’s “montage of attractions” or Pudovkin’s idea of “linkages.” Although the contribution by Soviet filmmakers to the genre is limited to Kaufman and Kopalin’s Moscow, Mikhail Kaufman’s Vesnoy (In Spring, 1929), Vertov’s Man with a Movie Camera, as well as parts of his Kinoglaz (Kino-Eye, 1924) and Shestaya Chast’ Mira (A Sixth Part of the World, 1926), and Bliokh’s Shanghai Document, many city symphonies are marked by Soviet-inspired montage practices. As non-narrative films, city symphonies are often structured according to rhythmic editing, the rapid succession of shots evoking the hectic rhythm of machines and the throbbing activity of the city streets. In addition, making observations on the conditions of urban modernity, many city symphonies also borrow associative, metaphorical, and dialectical montage techniques from the Soviet cinema. In so doing, the attention for the spatial and social contrasts in the modern city is emphasized by visual juxtapositions through editing: high-angle and low-angle shots, panoramic views and close shots at street level, darkness and light, et cetera. Through editing and camera work, city symphonies present the city as an optical spectacle. Given this perspective, many city symphonies are not only marked by Soviet montage but also by the impressionist aesthetics of the French cinéma pur. This is particularly the case in Chomette’s Jeux des reflets et de la vitesse and Deslaw’s Les Nuits éléctriques, both of which were made by directors working in the context of the French avant-garde. In addition, the city symphonies made by Sheeler and Strand, Ivens, Storck, Sauvage, Kaufman, Lacombe, Carné, de Oliveira, and Weinberg share the impressionist fascination for the photogénie of atmospheric effects and the flux of ephemeral phenomena, such as light, smoke, clouds, and water.

Characterized by rhythmic and associative editing and an impressionist sensibility for atmospheric effects, city symphonies have been described frequently as city poems. Eschewing expository sequences, these films tend toward poetry rather than prose—in the case of Manhatta, this tendency is explicit, as the film includes intertitles based on Walt Whitman’s Leaves of Grass as a key element of its form. However, it is significant that these films became known primarily as city symphonies and not city poems, that they may have pursued a form of ciné-poetry, but that frequently they avoided text or any other kind of narration in favor of the abstraction of musical rhythms and structures the way Ruttmann’s famous film on Berlin had in 1927.42 In the wake of Berlin: Die Sinfonie der Grosstadt, several other films include the term “symphony” in their title or subtitle: Sinfonia de Cataguases (Symphony of Cataguases, Humberto Mauro, 1928), Skyscraper Symphony, São Paulo: A Symphony of the Metropolis, the anonymous Japanese film Symphony of the Rebuilding of the Imperial Metropolis, and A City Symphony (Herman Weinberg, 1930).43 Other musical terms pop up in other titles such as Études des mouvements à Paris, Études sur Paris, Harmonies de Paris, Mélodie bruxelloise (Brussels Melody, Carlo Queeckers, 1929), Manhattan Medley, Ritmi di stazione, and Rhapsody in Two Languages. Moreover, many city symphonies self-consciously adopt a musical structure, and are frequently organized in terms of “movements.” Ruttmann’s Berlin, for instance, is divided into “acts,” each one dominated by a certain pace and rhythm as a result of which the entire film can be compared with a musical piece consisting of an allegro, andante, and a presto. Largely based on the rhythmic organization of images through editing, city symphonies took their cue from abstract experimental films that looked to music in order to find form, such as Hans Richter’s 1921–25 Rhythmus series, Viking Eggeling’s 1924 Symphonie diagonale, and, of course, Ruttmann’s 1923–25 Lichtspiel series, which carry the subtitles Opus 1 through 4. The link with these experiments in “visual music” is even made explicit in Ruttmann’s Berlin and Ivens’s De Brug, both of which open with abstract animation sequences, showing an interest in abstract painting, as well as a desire to bridge the realms of abstract art on canvas and in galleries and the abstract forms found in the everyday world.

These links between the filmmakers who were responsible for the city symphonies of the 1920s and 1930s and the art world were both numerous and strong. Several directors of city symphonies such as Paul Strand, Charles Sheeler, Walter Ruttmann, László Moholy-Nagy, André Sauvage, Paul Schuitema, Ralph Steiner, and Willard Van Dyke were active as painters, photographers, or graphic designers whereas Dziga Vertov, Joris Ivens, Charles Dekeukeleire, Henri Storck, Alexandr Hackenschmied, Eugène Deslaw, and Jay Leyda were all actively involved in avant-garde art circles. Many shots and sequences of city symphonies evoke the imagery of the art movements of 1910s and 1920s such as Cubism, Futurism, Dadaism, Constructivism, the New Objectivity, or Surrealism, in which the modern city is a key topic.44 Most of the visual motifs of city symphonies—motorized traffic and crowds, industrial activity and leisure, high-rise structures and skyscrapers, billboards and shop windows—also feature abundantly in the paintings, photographs, collages, and photomontages of vanguard artists of the era. Furthermore, the cinematography of many city symphonies echoes the fragmented compositions, canted angles, and unusual perspectives favored by these artists whereas cinematic devices such as hectic editing, nervous camera movements, split screens, and multiple exposures contribute to the evocation of a hectic and kaleidoscopic urban environment. Even films that tend toward the expository, such as Prater or São Paulo, also include emblematic shots marked by special effects evoking the kaleidoscopic nature of urban modernity. In particular, these shots evoke the famous photomontages by Dadaist and Constructivist artists such as John Heartfield, Hannah Höch, Paul Citroen, Gustav Klutsis, László Moholy-Nagy, Alexander Rodchenko, and Kazimierz Podsadecki, which depict the modern metropolis as a kaleidoscopic simultaneity of fragments. Evoking associations with the machine and engineering, photomontages also made visible the process of their own making, thus answering to the avant-garde principle of self-reflection.45 City symphonies transposed these procedures to film, a medium inherently marked by editing and hence the juxtaposition of images and, at that time, under the influence of Soviet montage experiments.

While the city symphony genre is most closely associated with the furiously paced montage found in some of the most renowned sequences in Berlin and Man with a Movie Camera, it is important to point out that other portions of these same films feature a very different approach to content and editing, which results in a sense of tempo and tone that is markedly more subdued, and which adds to the tensions that Ruttmann and Vertov are working with. Many city symphonies made great use of such contrasts in tempos and approaches to editing, but some preferred to maintain such a steady, measured pace throughout, and in some notable cases we see a shared interest in the urban imagery found in Surrealism, with its absurd juxtapositions and oneiric strollers. It is primarily in a group of city symphonies made in France, Belgium, Holland, and Portugal that one finds the strongest affinities with the photography of artists who were affiliated with the Surrealist movement, either as active members or as inspirations or fellow travelers, artists such as Eugène Atget, Jacques-André Boiffard, André Kertesz, Brassaï, and Eli Lotar, although Leyda’s A Bronx Morning which was directly inspired by Atget’s images of the strange sights found in shop windows, stands as a notable exception.46 In contrast with the darkroom experiments of other Surrealist artists (double exposures, photograms, solarization, montages), these photographers attempted to show the surreal in the real, exploring the marvellous and the startling in the mundane spaces of the city, and they inspired these filmmakers to do the same. This is particularly the case in the films that explore derelict spaces of the city, as well as the uncanny of modern city streets devoid of traffic.

Not unlike Dadaist, Constructivist, or Surrealist artworks, city symphonies frequently attempt to disorient their spectators or to defamiliarize their subject matter. In so doing, they present themselves as part of the culture of the avant-garde. Apart from showing formal similarities with the vanguard visual arts of the day and using abundantly experimental techniques, they also are marked by an avant-garde interest in self- reflexivity. Apart from representing urban modernity, city symphonies reflect on the ways cityscapes are the cinema’s ultimate subjects. Celebrating the dynamics of industrial speed and the frenetic pace of modern urban life and its highly fragmented and kaleidoscopic nature, city symphonies take the pulse of the city and quite literally translate it into the rhythm of cinema. They make explicit the connection between film spectatorship and the stimulus-response mechanisms said to be produced by metropolitan modernity and its sensory overload.47 The dynamic and fragmented structure of cinema is presented as being an extension of the city itself—the shifting perspectives, the pace of the editing, the special effects are all presented as both expressions and products of modern metropolitan life. City symphonies, thus, indicate that cinema is the ultimate medium to depict the city or, conversely, that the city was the ultimate subject matter for the camera-eye. In other words, the city symphony demonstrates the correspondence between the flash-like and disjointed succession of images inherent to cinema and the receptive disposition of the modern city-dweller. Given this perspective, the city symphony reached its most radical expression in Man with a Movie Camera, as this film not only deals with the city but also, in a highly self-reflexive way, with its cinematic representation.

Reaching its apex in 1929, the city symphony phenomenon coincides with and is generative of the avant-garde’s “documentary turn.” Facing a large-scale reorganization of the production and exhibition of films following the introduction of sound in the late 1920s, as well as the rise of fascism, many progressive and independent filmmakers turned to documentary representation as a means of expression.48 So, for instance, in 1931, having made the city symphonies De Brug and Regen, Joris Ivens wrote that the “documentary film is the only means left to the avant-garde cinéaste” in his battle against the big film studios, and that “in the current state of the cinema, documentary provides the best means of discovering the cinema’s true paths.”49 Clearly, these “true paths” included the cinematic exploration of both the most spectacular constructions and the mundane elements of urban modernity as seen in so many city symphonies. Moreover, many city symphonies depicted the metropolis as a site of social contrasts, drawing the viewers’ attention to overlooked spaces and neglected communities. However, this social critique was always combined with formal innovation and stylistic experiment, frequently provoking the reproach of a “formalist” agenda or art-for-art’s-sake aspirations. Kracauer, for instance, noted the “surface approach” of Ruttmann’s editing, which “relies on the formal qualities of the objects rather than on their meanings,” emphasizing “pure patterns of movement.”50 Even when Ruttmann juxtaposes hungry children with opulent dishes in some restaurant, these contrasts “are not so much social protests as formal expedients,” according to Kracauer.51 Likewise, facing the dozens of variations on Ruttmann’s film, Paul Rotha stated that these films were

inspired by nothing more serious than kindergarten theory, their observations on the contemporary city scene being limited to obvious comparisons between poor and rich, clean and dirty, with a never-failing tendency towards rhythmic movements of machinery and the implications of garbage cans. Providing excellent fodder for the film societies, these films were typical product of an art- for-art’s-sake movement.52

The emphatic fascination for the modern metropolis among filmmakers and visual artists in the 1920s was hardly an isolated phenomenon. The era of the city symphony was also the golden age of the modern urban novel, which saw the publication of James Joyce’s Ulysses (1922), John Dos Passos’s Manhattan Transfer (1925), Louis Aragon’s Le Paysan de Paris (1926), André Breton’s Nadja (1928), and Alfred Döblin’s Berlin Alexanderplatz (1929), among many others.53 These literary and artistic representations and evocations of the city are, of course, inherently linked to the accelerated processes of urbanization and modernization that characterized the entire Western world after the First World War. Most if not all of the city symphonies discussed in this book can be seen as responses to the startling changes that came with this. For novelists, poets, artists, and filmmakers, the city was the stage of modernity, the place where the processes associated with modernity—capitalism, socialism, industrialization, rationalization, social mobility, alienation, mass consumption, et cetera—were most glaringly visible. Modernity and metropolis came to be seen as inherently intertwined concepts, the one being used to describe or to explain the other. From the late nineteenth century onwards, theorists such as Georg Simmel noticed that the modern city also entailed new modes of perception and experience, creating a new psychological condition for urban dwellers. Simmel interpreted the metropolis as a web or network of intersecting spheres, the locus of various intellectual and cultural circles, a place marked by the division of labor. However, for Simmel, the metropolis is a realm characterized by flux: a place where ever-new needs and short-lived fashions are constantly being created, and that is characterized first and foremost by the accelerated commodity exchange of the modern money economy—the key topic of his 1900 Philosophie des Geldes (Philosophy of Money).54 In Simmel’s analysis, the city is a sphere of circulation and exchange, in which differences of value and class are obscured. These notions are also central in his oft-quoted essay “Die Grossstädte und das Geisteleben” (“Metropolis and Mental Life,” 1903), in which he analyzes the effects of the big city on the mind of the individual.55 For Simmel, life in the modern metropolis is characterized by a continuous flow of stimuli to the senses. The spectacle of anonymous crowds, motorized traffic, colorful shop windows, and bold billboards brings about an intensified form of sensory stimulation. Simmel speaks of “the intensification of nervous stimulation” induced by the rapid crowding of changing images, the sharp discontinuity in the grasp of a single glance, and the unexpectedness of onrushing impressions. This hyperstimulation is almost suffocating, resulting in phenomena such as stress and shock (both of which were often interpreted as a syndromes that were symptomatic of modern city life). As a result, metropolitan dwellers created a distance between their inner selves and the tumult of impressions generated by the big city. Because living in the modern metropolis would become unbearable without this psychological distance, the modern urbanite had developed a defense mechanism against overstimulation: the blasé attitude.