László Moholy-Nagy is remembered mostly as a visual artist who worked in photography, painting, and sculpture, while his oeuvre as a filmmaker remains largely unknown. The Hungarian born polymath also gained recognition as a teacher and educator, first at the German Bauhaus from 1922 to 1928 (in Weimar and Dessau), later as the founder of the School of Design in Chicago in 1939. Arguably one of the central artists of the first half of the twentieth century, Moholy-Nagy explored the basic properties of artistic production in various media, such as light and shadow, movement and stasis, material and perspective. The modern city was one of the central topics of his work and consequently this thematic preoccupation can be found across the wide array of his different artistic, organizational, and didactic endeavors. It comes as no surprise that the city appears prominently in his filmic work as well, on which I will concentrate in this essay, but with an artist such as Moholy-Nagy it is practically impossible to limit oneself just to one medium.

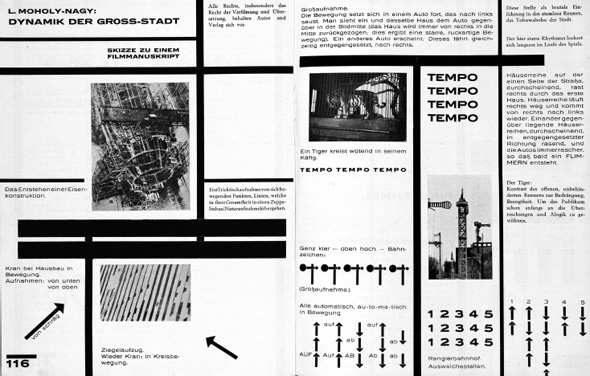

Moholy-Nagy can be considered as one of the founders of the city symphony genre, as he created one of its earliest examples, albeit in writing, photography, and design, a multi-media work he himself termed a “typophoto.”1 First conceived probably around 1921/22, and subsequently published in Hungarian in September 1924, his screenplay Dynamik der Gross-Stadt (“Dynamic of the Metropolis”) made a lasting impression in its 1925 republication as part of his Bauhaus-book Malerei Photographie Film, which included photographs and was marked by the use of bold modernist design. This text can be considered as a “city symphony on paper” and a model for many of the genre’s classics, which would appear in the years to follow, including his own contributions to the cycle of city films.2 The modernist collage exhibits equal interest in the new visual configurations that the city affords and in the optical possibilities of the relatively new medium of film. With its conscious and persistent employment of superimposition, forced perspective, reverse motion, slow motion, and many other tricks, it is a veritable companion of the visual possibilities of the camera and of post-production. A film based on the script was never shot and it is one of many unrealized plans in Moholy-Nagy’s career, who constantly generated new ideas.3 In fact, it has been argued that due to its experimental visual design, Dynamik der Gross-Stadt was not even meant to be realized, but in all likelihood, it influenced Walter Ruttmann, who knew Moholy-Nagy’s influential book.4 At first sight, Moholy-Nagy’s juxtaposition of text, images, and graphic elements on the flat surface of the page appears to owe more to the simultaneity of the collage than to the temporal sequence of montage. Yet, the arrangement of these different elements, the interest in graphical composition, and the insistence on the social diversity of the urban environment point forward to Moholy-Nagy’s engagements with the city as a multi- faceted and open-ended entity. Most importantly, it stands in line with the interest in the city as an environment that at once demands and creates different modes of perception—by necessity, human perception and the reality of the urban stand in a mutual process of co-evolution that leads to ever higher levels of complexity.

Of course, the modern metropolis became one of the key topics of modern art in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries—in painting (Impressionism, Expressionism, Fauvism, Constructivism, Futurism, et cetera), literature (James Joyce, John Dos Passos, Alfred Döblin), and other artistic forms, it has inspired and driven artists to new and innovative forms of expression.5 Moholy-Nagy’s script is a fascinating hybrid that attempts to find an aesthetic form for the experience of the modern city by combining text, images, and graphic composition. In this sense, the script is more “than merely a storyboard for an unrealized film, both the Hungarian and German versions … suggest themselves as kinetic works of visual and verbal poetry that mimic the dynamism of their subject.”6 The terms “script” and “scenario” might indeed be misleading in that they position the cinema as the natural and given telos of the ideas expressed in the manuscript. In fact, the text is a rather an open-ended investigation into the perceptual dynamics that the city necessitates and that the typoscript proposes. In this sense, the manuscript could be said to point forward to and anticipate Walter Benjamin’s idea of cinema as the “training ground” of perception, as it attempts to replicate a complex multi-media environment in a performative form.7 It is not the similarity of the images, texts, and graphical elements to specific configurations in the city that is at stake in Moholy-Nagy’s work, but rather an isomorphism with regards to the perceptual dynamics stimulated by the urban. It is furthermore exactly the dynamism of the composition that echoes and mimics the way the city challenges human perception constantly; no fixed form such as a monument or a painting could render the city adequately because movement and relational dynamics require a spectatorial position that is likewise destabilized and constantly in motion.

Moholy-Nagy’s position can only be fully understood if considered in relation to his theoretical writings. In one of his key texts, “Production—Reproduction,” first published in 1922 in the magazine De Stijl, Moholy-Nagy proposes to move from artistic work concerned with the reproduction of the existing reality to works concerned with the production of new relations: “Since it is primarily production (productive creation) that serves human construction, we must strive to turn the apparatuses (instruments) used so far only for reproductive purposes into ones that can be used for productive purposes as well.”8 This argument provides a key to understanding his work on the city—a complex configuration such as the city perpetually generates new and different relations, so the city dweller is forced to constantly produce new schemata and mechanisms to cope with the environment. In a formulation that brings to mind key aspects of Marshall McLuhan’s Understanding Media (1964), Moholy- Nagy describes art and aesthetic experiences as perceptual extensions of the human system that are capable of supporting, mediating, and enhancing these reactive functions which, ultimately aim at coping with perceptual overload, shock, and confusion.9 In this perspective, art is not providing mimetic representations of a pre-existing reality, but it is rather generating this reality through the productive employment of its different techniques.

The city as a topic can be traced through Moholy-Nagy’s overall filmic, photographic, and theoretical work from the 1920s to the 1940s. While his first filmic work Impressionen vom alten Marseiller Hafen (Vieux Port) (Impressions of the Old Marseille Port, 1929/1932) includes impressive footage of the pont transbordeur in the harbor of Marseille, a landmark of modern engineering filmed in Moholy-Nagy’s characteristic constructivist style favoring high angles, tilted views, and graphical compositions verging on the abstract, the film also contains scenes shot in the city’s popular quarters, marking his interest in the documentation of social reality to be found in the margins of urban environments. The film opens with a map of Marseille in which the area of the old port is cut out from below with a pair of scissors. As soon as the cutting is completed, a film starts within this cut-out surface, effectively merging the cartographic space of the map with the actual documentary images. Moreover, Moholy-Nagy’s characteristic constructivist, multi- perspectival approach can be found in views of bustling traffic shot from above and filmed through the grids of balconies, but the film also contains documentary images of city life less obsessed with novel visual composition and rather interested in observing the life of people in the city. In some scenes, characters acknowledge the presence of the camera through direct address and a look into the lens, while other scenes appear to have been filmed with a hidden camera. The heterogeneity of the city, as well as the many different forms in which film and photography as media can present this formation in ever novel ways became a central topic for Moholy-Nagy, as his “modernist approach theorized that the only way to liberate audience consciousness was through the use of multiple perspectives, whereby it was up to the viewer to construct an objective vision through the act of reception.”10 Like his earlier script on the dynamic of the metropolis, the film does not follow the typical structure of “a day in the life,” but instead explores just a smaller section of the city. Moholy-Nagy’s distance from the narrative model is telling, just as he turned his own limitation—he had limited raw material at his disposal—into a conscious decision on the part of the filmmaker.11

Berliner Stilleben (Berlin Still Life, shot probably in 1931/32, even though some sources give 1926) shows the city and its vibrant life in a social realist spirit. The film opens in the better bourgeois quarters of Berlin with a signature high-angle shot of children playing on a boulevard taken from a balcony (quite possibly from Moholy-Nagy’s own flat) and then proceeds with a streetcar ride into the dirty tenement houses of Wedding, where it shows an eviction, children playing in dirt, and other stereotypical images of poverty and poor living conditions. It has consequently been seen either as a social documentary and accusation of injustice, or it has been interpreted as an exercise in “slumming,” the expedition of a bourgeois artist into the underbelly of the city. The film’s “impressionistic, tourist perspective” exhibits a fascination with dirt, decay, and rubble.12 Yet again, the film concentrates on the most visible material surfaces of the city that are normally ignored—the paving and concrete of the streets, the bricks and plaster of the façades, the shadows and reflections created by light. The shots are often presented in odd and stark angles so typical for the city symphony genre, yet they defy the logic of “a day in the life” which characterizes the majority of this cycle of films. The formal parameters, such as mise-en-scène, montage, and camera movement, emphasize the constriction and lack of space that characterize the working-class boroughs of Berlin and other industrial cities. However, the overall structure of the film accepts poverty and misery as given conditions, the roots and causes of social imbalance remain beyond the scope of the film. The film is typical of Moholy-Nagy’s cinematic approach in that it features a poly- focal array of perspectives and modalities aimed at forcing the spectator to adopt different point of views, while, at the same time, the film avoids digging too deeply into social, political, or other causes.

While Moholy-Nagy’s Impressionen and Stilleben appear somewhat improvised and spontaneous, they also correspond with more conceptual considerations put forward in his texts. For Moholy-Nagy, it was the act of reception that put the various perspectives and aspects of the city back together, it was the viewer that was necessary for creating a synthesis and making sense of the disparate elements. Consequently, a 1927 essay addressed the act of reception by proposing a so-called “polykino,” a cinema with a variable screen and projection apparatus in which the format could be adapted according to the presented images. The aim of such an apparatus was, as always with Moholy-Nagy, to train the perceptual capabilities of the spectators: “The vast development both of technique and of the big cities have increased the capacity of our perceptual organs for simultaneous acoustical and optical activity.”13 Time and again, Moholy-Nagy’s art investigated the new perceptual possibilities afforded by modern life and technology, but in this case not within the filmic texture itself, but transferred to the reception situation. Here, Moholy-Nagy’s ideas were in tune with his contemporaries such as Siegfried Kracauer and especially Walter Benjamin who believed that the tremendous changes brought about by modernization had to be approached dialectically, taking stock of both of the losses and of the potentials of modern media.

At around the same time Moholy-Nagy shot what is probably his most well-known filmic work: Ein Lichtspiel: Schwarz—Weiss—Grau (1932), made as a companion piece to his sculpture Lichtraummodulator. Unlike his other films, this work has entered the canon of experimental cinema because it is more easily classifiable as a (largely) abstract film dealing with light, shadow, and reflection created by a kinetic sculpture. Indeed, this design was very similar to the one Moholy-Nagy employed for the special effects on the H.G. Wells adaptation Things to Come, shot only a few years later in London, but there it was used to very different ends.14

Moholy-Nagy’s filmic activities were not limited to works that provide cross-sections of the city, but it also encompassed films that approach documentary formats dealing with one specific topic. In the spring of 1932, he shot what came to be known as Gross-Stadt-Zigeuner (Urban Gypsies 1932,), a 12-minute film focusing on gypsies living in a peripheral zone of Berlin.15 The film was never shown publicly prior to Moholy-Nagy’s death and exists in at least two different versions, which, as Robin Curtis has argued, encourage either an optical or a haptical mode of reception.16 In the perspective provided by the former, the film’s use of authoritative voice-over pities the gypsies and their desperate lives among dismal living conditions, as well as commenting on how their superstitions have contributed to their appalling state. The other version fits within the cycle of city films—if we understand them ultimately as a perceptual experiment geared towards developing new forms of sensory stimulation—as part and parcel of Moholy-Nagy’s investigation of different experiential registers and intermodality. The hand-camera and the sudden cuts underline the subjective experience of the visit to the gypsy camp: “Such images produce, firstly, an unusually strong impression of kinaesthetic or haptic perception and secondly, point unavoidably to the presence of Moholy-Nagy behind the camera.”17 Unlike many other city films in which either a given structure—e.g., a symphony (as in the case of Ruttmann), or the capabilities of the medium beyond human intervention (as in the case of Vertov)—are taken as starting points for the films, Gross-Stadt-Zigeuner clearly presents a subjective approach to the topic.

In the summer of 1933—Moholy-Nagy seemed to have not yet made up his mind whether to stay in Germany or whether to leave for good—he took the opportunity to film Architekturkongress (Architectural Congress, 1933,), a filmic documentation of the famous CIAM Congress on modern architecture, featuring many luminaries of the epoch such as Le Corbusier and Fernand Léger. The conference took place during a cruise in the Mediterranean from Marseille to Athens and back over the course of two weeks, from 29 July to 13 August, 1933.18 The film resembles an amateur travel film more than it does a serious engagement with the topic of the meeting: “the functional city.” This “mixture of a favor for friends and interesting opportunity to work in the context of international and interdisciplinary avant-garde connections” nevertheless exhibits some of Moholy-Nagy’s trademarks.19 The film begins with shots of the pont transbordeur taken from Impressionen vom alten Marseiller Hafen, while the scenes on board and during the port of call excursions mirror Moholy-Nagy’s interest in fluid hand-held camerawork. Even though we do not really come to understand the topic of debates and lectures, it is evident that Moholy-Nagy is interested in the different visual registers of the trip: we repeatedly see different city maps that accompany the talks and incidental happenings, as well as touristic impressions of the Greek capital and islands, but also strong graphical structures tending towards abstract and geometrical shapes and many overhead shots, both of which had become something of a Moholy-Nagy signature. Despite these preoccupations, the film remains more of a social “diary” of the events than an insightful examination of the theme underlying the conference.

During his first exile in Great-Britain, a different attempt to deal with the city as a topic can be seen in Moholy-Nagy’s contribution to the big-budget science-fiction film Things to Come (William Cameron Menzies, produced by Alexander Korda, 1936,), for which he was hired as a designer of special effects and for a specific sequence showing the city of the future. Of his design, only interspersed shots were used in the finished film, a disappointment for the artist who was hoping for a breakthrough in commercial filmmaking.20 This detour into mainstream movies remained an exception in Moholy-Nagy’s career, who subsequently only shot commissioned films.

The New Architecture at the London Zoo (1936) is an example of such a commission. He received it from the Museum of Modern Art in New York in order to document recent architectural developments at the London Zoo, as the title suggests. This institutional endorsement was geared toward a marriage of modern architecture and its dynamic portrayal in a modern form. The film has often been seen as a rather straightforward and traditional documentary, but it does show some of Moholy-Nagy’s typical trademarks. The film exhibits movement and stasis both of architecture as well as the image by extensive movement of the camera (travelling, pans). As in previous films, a mixture of text, graphics, and photographic aspects give a specific and mediated impression of an environment, in this case the new buildings. Textual descriptions in titles, sketches, and floor plans, as well as shots of the actual buildings from different angles and perspectives show the complexity of the architecture, as well as the different registers needed to adequately reflect this in cinematic form. The film is an exercise in how to transpose modern architecture into film which, as Benjamin remarked, is experienced through use, into a different form which typically employs a mixture of different aspects and perspectives instead of limiting oneself to just one perspective.21

The filmic work of László Moholy-Nagy does not easily fit into the standard understanding of the city symphony. However, the relationship of these films to Moholy-Nagy’s larger artistic and theoretical preoccupations provides us with an invaluable understanding of the context out of which the city symphony emerged. More specifically, the series of short films and mixed media texts, produced over a period of roughly 15 years, highlight various aspects and modulate central concerns of the urban, and of modernity more generally, as seen by Moholy-Nagy. Nevertheless, they do not limit themselves to one overarching perspective or position. In its variety of topics, styles, and manners of addressing the spectator, as well as in the different ideas of what the cinema could be in terms of its production context (amateur film, commissioned film, independent artists’ cinema, filmic diary), this body of work present the modern city as a complex and multi-dimensional environment that can never be grasped in its entirety. Instead, the films share a poly-focal approach to a similarly poly-focal topic.

Nevertheless, certain interests typical of Moholy-Nagy’s work can be traced all through the films: slanted and overhead perspectives abound in the films, but also alternate with documentary glimpses into city life, especially in the poorer quarters, as well as different visual registers (maps, graphs). Despite this marked interest in social differences, the films do not inquire into the social and political causes behind inequality, but they turn toward a Constructivist fascination with patterns, forms, and visual structures, which is manifested in the change of perspectives and points of view. While they may not show political engagements with questions of inequality and segregation, Moholy-Nagy’s complex approach toward the visual dynamism of the urban environment continues to fascinate and inspire viewers until today.