Figure 2.1 Kleiner Film einer großen Stadt … Der Stadt Düsseldorf am Rhein (Walter Ruttmann, 1935)

In June 1935, planning began in Düsseldorf for what would become the largest exhibition of the Third Reich with some seven million visitors: Schaffendes Volk: Große Ausstellung Düsseldorf Schlageterstadt 1937 (Productive Volk: The Great Exhibition of Düssseldorf Schlageterstadt 1937). Although less well-known today than the Degenerate Art exhibition held in Munich the same year, Schaffendes Volk was undoubtedly the more important event for the Nazi government, intended as it was to showcase the “productivity” of the new regime—in particular the “four-year plan” of industrial investment, public works, and rearmament—to the outside world. But Schaffendes Volk also offers a good example of urban rebranding after 1933. Düsseldorf was already known as Germany’s premier city for art and exhibitions, where the largest exhibition of the Weimar Republic—the famous GeSoLei exhibition of hygiene (Gesundheitspflege), social welfare (Soziale Fürsorge) and physical exercise (Leibesübungen)—had taken place in 1926. In many ways, Schaffendes Volk drew on the GeSoLei legacy, but the new exhibition, as the title “Schlageterstadt” suggests, featured an entirely different symbolic geography. Rather than occupying the existing exhibition buildings and grounds, it was laid out to the north of the city around the memorial for Leo Albert Schlageter, a member of the German Freikorps executed by occupying French troops in 1923 and subsequently mythologized by the Nazi party as a resistance leader and “the first soldier of the Third Reich.”1 Erected in 1931 on the site of the execution, the Schlageter memorial had become an integral part of Düsseldorf’s urban identity after the Nazi seizure of power, its massive steel cross featuring prominently in every guidebook to the city. Capitalizing on this iconic status, the organizers of Schaffendes Volk transformed the fields around the memorial into a new housing district—the “Schlageter district” (today the Siedlung Golzheim)—to emphasize the exhibition’s broader role as witness to the “rebirth” of the nation and its industry.

The same year that planning for Schaffendes Volk began, the Propaganda Office of the city of Düsseldorf also commissioned another project in which both the Schlageter monument and the brand image of the “productive city” figured centrally: Walter Ruttmann’s Kleiner Film einer großen Stadt … der Stadt Düsseldorf am Rhein (Small Film for a Big City … the City of Düsseldorf on the Rhine, 1935). For any city commissioning a filmic portrait, Ruttmann (who himself had created the film advertisement for the GeSoLei exhibition in 1926) was an obvious choice. Not only had he pioneered the city symphony form with his Berlin: Die Sinfonie der Großstadt of 1927. By 1935, he had also become a go-to expert for short form promotional films. Ruttmann had already made two such films for the newly founded Office of the Reich Peasant Leader (Stabsamt des Reichsbauernführers), Blut und Boden (Blood and Soil, 1933), and Altgermanische Bauernkultur (Ancient German Peasant Culture, 1934), as well as one film for the German Council on Steel Usage (Beratungsstelle für Stallverwendung), Metall des Himmels (Metal from the Sky, 1934–5). In 1935, after taking up a full-time position in the advertising department of the Ufa, he then embarked on a series of films on the subject he was best known for, creating city portraits of Düsseldorf (1935), Stuttgart (Stuttgart. Die Großstadt zwischen Wald und Reben, 1935), and later Hamburg (Welstrasse See—Welthafen Hamburg, 1938).

Commissioned directly by urban PR departments and produced under the aegis of Germany’s largest film company, these miniature city films (of approximately 15 minutes) have a decidedly different feel from Ruttmann’s Weimar work. In Berlin, Ruttmann had sought to convey the experience of the modern industrial city as such, depicting it as a “complex machine,” whose daily cycles of work and leisure served to manage the sheer excess of bodies, traffic and information circulating within it.2 To this end, he also avoided focusing on famous monuments, depicting Berlin rather as a collection of “any-spaces-whatever”—of streets, canals, offices, factory floors, restaurants, theaters, cinemas, sports arenas, et cetera.3 By contrast, Ruttmann’s later city portraits were explicit exercises in branding, which sought to demonstrate the city’s role in the national “reawakening” after 1933. The Stuttgart film, for example, showcased the city’s traditional tourist destinations, while also foregrounding modern building projects and above all Stuttgart’s new role as the “City of Germans Abroad” (Stadt des Auslanddeutschtums) and home of the Deutsches Auslands-Institut, which had become the headquarters for efforts to propagate National Socialist ideology to Germans living abroad.4

Düsseldorf undertakes an analogous branding operation. Far from the nameless spaces of labor and leisure foregrounded in Berlin, the film highlights one highly symbolic place after another. From the opening titles displayed over the famous monument of the Duke Jan Wellem, Ruttmann then takes spectators on a virtual tour of signature sites and architecture: the ruins of Barbarossa’s imperial palace in the Kaiserswerth district; the houses of the Altstadt; the Rheinhalle and planetarium (originally constructed for the GeSoLei); the Königsallee with its exclusive shops and terrace cafes; or the Imperial Gardens (Hofgarten) with its famous sculptures and fountains (e.g., the Märchenbrunnen and the “Grüner Junge”); at the same time, the film highlights—in a manner reminiscent of Metall des Himmels—Düsseldorf’s “productivity” through a focus on key industrial buildings, such as the offices of the Henkel conglomerate, the Stahlhof (home of the Association of Steel Works), and the headquarters of Mannesmann steel production (designed by Peter Behrens). This is, indeed, the same combination of places highlighted in contemporary guidebooks, and Düsseldorf is, by any measure, a tourist film, modeled broadly on contemporary guidebooks, which themselves sought to rebrand Düsseldorf from an “art and garden city” to a center of steel production.5

This focus on symbolic places finds an echo in the film’s symbolic temporality. Whereas Berlin condensed its action into a single random day—an “any-day-whatever”—to convey the typical functioning of the urban apparatus, Düsseldorf, as Carolyn Birdsall has pointed out, follows a ritual timeframe by highlighting urban festivals and rituals over the space of a single year, from the opening shots of January Carnival celebrations to the closing sequence featuring the traditional St. Martin’s festivities in November (where children’s choirs descend into the streets).6 Between the two, the film features a lengthy sequence of the annual July fair organized by the St. Sebastianus Schützenverein, which was celebrating its 500th anniversary during the filming of Düsseldorf in 1935. Here, too, one can find direct equivalents in the guidebooks.7

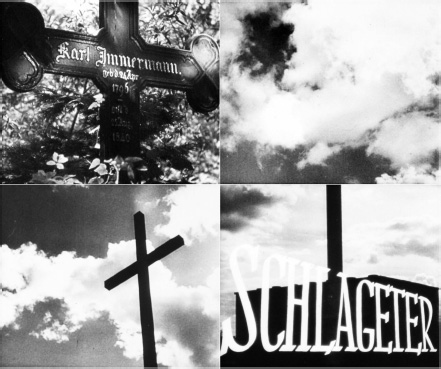

Within this parade of privileged times and places, Düsseldorf carefully avoids any overt references to National Socialist party politics.8 Nonetheless, the film is at pains to represent a new city fit for new times. Many of the sites foregrounded in the film were explicit “achievements” of the Nazi government, including the newly rebuilt railway station (1932–6) and the extension of the silos at the Plange mill (1934). At the same time, the film strives to imbue Düsseldorf with a sense of history, giving particular attention to the all-important Schlageter monument. Just after the opening shots, featuring a parade of carnival masks, the film cuts to a different kind of mask: a series of death masks—followed by gravestones—of significant artists and intellectuals (the “sons of the city”): the authors Karl Immermann and Christian Dietrich Grabbe, the painters Peter von Cornelius and Alfred Rethel, and the composer Robert Schumann. Notably absent is the city’s most celebrated poet Heinrich Heine, whose works had been banned. This parade of founding figures then culminates in a sweeping camera movement, which pans through the sky to land on the 88-foot cross of the Schlageter memory site. As one review published just after the film’s premiere on 15 November 1935 described it, the sequence served to link two types of “heroes”: “This soaring upward movement of the camera is like a soaring up of the spirit—a symbolic image, whose wondrous arc binds together the heroes of the spirit and the fighter for the new times.”9 The reviewer’s language here recalls, once again, contemporary guidebooks, which touted the monument as the site where “the German hero revolted and German spirit raised itself up.”10 Forming the culmination of an illustrious line of forefathers, the Schlageter monument thus serves in Ruttmann’s film to inscribe the list of “Dichter und Denker” into a narrative of national sacrifice and national “reawakening.”11

Indeed, the “soaring” camera movement of the Schlageter sequence can be understood in analogy to other Nazi ritual performances of that same narrative and national resurrection. In Leni Riefenstahl’s Triumph of the Will (for which Ruttmann himself had shot a prologue that was ultimately excised), one such performance is on view in a scene where the names of WWI battles are called out as the Nazi flags are gradually lowered to the ground, only to be lifted up toward the sky as the speakers of the workers’ brigades explain that the martyrs of Nazism’s prehistory are not dead: “You are not dead. You live in Germany.” In the Schlageter sequence, Ruttmann’s camera movement performs a similar gesture. As the names of illustrious ancestors appear one by one along with their death masks, the camera leads the gaze of spectators downward toward the gravestones and eventually to the earth (quite literally in a tilt downward from the Immermann gravestone). As the musical score grows more solemn, the camera then abruptly turns upward to the sky and—through a conspicuous dissolve of clouds—lands on a low-angle shot of the Schlageter cross. Not unlike other Nazi commemoration ceremonies, Ruttmann’s camera here performs a “resurrection” of fallen heroes, whose sacrifice is redeemed through a rebirth of the German nation.

The “wondrous arc” of the Schlageter sequence in fact forms part of a broader pattern of camera movement in Düsseldorf. Unlike the mostly stationary shots of Berlin, the camera in Düsseldorf is in constant motion. On one level, as Lutz Philipp Günther suggests, such pervasive camera movement forms part of the film’s tourist mission, taking viewers on “phantom rides” through the city streets.12 Indeed, the film is full of the kinds of pans, tilts, and travelling shots that imitate the gaze of a tourist surveying the city, its monuments, vistas, buildings, and skylines. In some cases, the film even mimics verbatim the suggestions of guidebooks on how to experience the city visually; for example, one sequence, in which a street-level shot of the Wilhelm-Marx-Haus (“Düsseldorf’s trademark” according to contemporary guidebooks) is followed by a panorama of the urban vista from the platform atop the same building, reproduces the instructions of contemporary guides to take the elevator to the top of the building for the best “long view” (Fernsicht) of the city.13

Within this system of camera movement, Ruttmann’s film places a key emphasis on verticality, as the camera tilts up and down to scan the facades of the city’s buildings. But as much as these shots function to imitate a tourist gaze, they also take part—not unlike the low-angle shots in Triumph of the Will—in a reverential observation of the newly awakened nation, and in particular of the German steel industry, whose central companies the film carefully identifies for spectators.14 Many of the companies featured here had already figured in Metall des Himmels, whose molten steel imagery Ruttmann also repeats in Düsseldorf in a lengthy sequence of steel production, and both Henkel and Mannesmann would go on to form subjects of independent promotional films by Ruttmann.15 All were key players in a central National Socialist narrative of “awakening” through reindustrialization and rearmament after the years of occupation, reparations, and demilitarization.

In this sense, Düsseldorf illustrates well how the formal means of experimental filmmaking could be applied to ideological ends after 1933. Indeed, such formal features included not only camera movement, but also montage, in particular Ruttmann’s signature use of visual and thematic parallels. In Berlin, the pervasive parallels between people, machines, and animals served to generate an effect of statistical “regularity,” showing what the city’s various actants typically do at given moments in the course of a day.16 After 1933, and in particular beginning with Metall des Himmels, a distinct change in Ruttmann’s editing patterns becomes visible, where such parallels no longer serve to convey regularities but rather a sense of historical continuity, whereby industrial production appears as the culmination of a long history of Germanic “productivity.”17

Düsseldorf offers a good example of this montage of continuity. Just after the Schlageter sequence, the film cuts to a field of tulips, followed by a landscape filmed through the window of a moving train, soon revealed as a train travelling to Düsseldorf from the surrounding countryside. In contrast to the famous opening sequence of Berlin, the smooth train-ride of Düsseldorf positions the city not as the embodiment of a technological modernity that “interrupts” nature, but as a city firmly “rooted” in the landscape. Shots of the tulips give way to trees gliding past the windows, then to the water of the Rhine flowing elegantly, and finally to the agricultural industry along the river banks, before turning to frolicking bathers, water-skiers, and sailboats on the river.

In a preliminary written sketch for the film, Ruttmann described his intention to show the city “embedded” in the surrounding landscape,18 and many of his visual parallels perform a similar function of “embedding” the industrial city in a deep tradition. Typical, in this respect, is a sequence in which Ruttmann cuts from the neoclassical Doric columns of the Ratinger Gate in the old city to the newly completed silos of the Plange Mill. The graphic match effects a juxtaposition of visual forms familiar from Ruttmann’s earlier work, but it also takes on a new ideological function of embedding industrial buildings within a national architectural tradition. Such uses of experimental film language were, in fact, a frequent trope of non-fiction filmmaking under Nazism. Guido Seeber featured similar parallels in his film Ewiger Wald (1936) to compare the rows of trees in the “eternal forest” to lines of Prussian soldiers, and Ruttmann himself would feature a similar use of montage in his Mannesmann film (1937), where the steel pipes of the Mannesmann factory dissolve into the trees of the forest around Remscheid where the factory was founded. Such parallels worked to convey a semiotics of “rootedness,” where industry appears as the outgrowth (rather than the interruption) of artisanal labor, where modern architecture builds upon (rather than supplanting) classical traditions, and where the city itself appears embedded in both history and the landscape. In this sense, Ruttmann’s montage in Düsseldorf strives to realize the project he laid out in an interview from 1935:

I would be happy if this idea … could provide me with the opportunity to create the epos of a German landscape, which would lead organically from the Stone Age through all of the nation’s historical struggles to the joy of Germany’s reawakening.19

The silo montage prefigures a more extended rhetorical parallel towards the end of the film. Just after a sequence showing the Imperial Gardens and their famous sculptures, the film takes viewers into a montage of artists at work. Reminiscent of the Schaffende Hände (Productive Hands) series of artist portraits created in the 1920s by Hans Cürlis, the sequence shows a series of sculptors, wood-cutters, metal workers, architects, and painters at work—all meant to represent Düsseldorf’s strong artistic and artisanal tradition. As the camera then tracks forward towards a painting of an urban industrial scene, Ruttmann cuts abruptly to a shot of a factory with smoke billowing from the chimney. On one level, this visual juxtaposition simply emphasizes film’s ability to bring still paintings to life. But like the cut from the Doric columns to the modern silos, it also establishes a semiotic “arc” leading from the “productive hands” of artisans to the industrial productivity of Düsseldorf’s steel factories, from the chiseling of wood, metal, and plaster to the forming of steel parts by giant factory machines. From the outdoor shot of the billowing smoke, the film then proceeds into the factory interiors: the packaging plant of Henkel, the pipe production of Mannesmann, and the myriad images of machines parts and molten metal that formed a recurrent motif in Ruttmann’s work from Acciaio (1933) to Metall des Himmels (1935) to Mannesmann (1937) to Deutsche Panzer (1941). The result of this transition from “productive hands” to “productive machines” is a rhetorical depiction of industrial Düsseldorf not as a break with the past, but as a “productive city,” whose traditions of artisanal labor flow “organically” into the modern production of steel factories. As the review of 1935 put it: “The sculptor’s cautious chisel work and the infernal pounding of the steel hammers—both activities are nothing other than witnesses of the same productive spirit [schaffenden Geistes] in the same city.”20

This celebration of “productivity” as the thread of historical continuity forms one of the central rhetorical arguments of Ruttmann’s post-1933 city portraits. In this sense, the lines spoken by a character in Ruttmann’s Stuttgart film could easily have served as the motto for Düsseldorf: “Motivation, proficiency and a sense of quality work … this has been our way down to the present day in manual labor as in industry, and this is why we have continued to improve steadily despite all the crises.”21 Like Stuttgart, and like Schaffendes Volk, Düsseldorf sought to convey this sense of national continuity through its many juxtapositions of hands and machines, countryside and city, ancient and modern architecture.

Unlike Berlin, which showed a city without history, Düsseldorf shows us a city shot through with places and traces of national memory: with the ruins of Barbarossa’s palace, the 500 years of the Schützenverband or the graves of the city’s many “heroes.” But the film also portrays these past figures as precursors and agents of a “sacrifice,” who led the way toward the heroic productivity of the newly industrialized city. In this sense, Düsseldorf takes part in a particular National Socialist narrative of urban “reawakening,” which would find another expression two years later in the exhibition Schaffendes Volk.