The city symphony—whether major or minor—is a mode of ambivalence. Laura Marcus writes that city symphony films “sought to renew the medium … by returning to cinema’s origins in the documenting of reality, but with the particular twist given by the perspectives and angles of modernism.”1 The “documenting of reality” obliges a film to record and report on a city’s particularity, while the “particular twist” provided by modernism—a tendency toward experimentation, innovation, and abstraction—might function to de-particularize the city or cities in question. Documenting and legitimizing the emerging reality of a particular modern city might often be as pressingly important as the obligation to formal experimentation. Moreover, the city in question may not be altogether so thoroughly modern; it may need the city symphony to make the case for its uneven or under-developed modernity. The film’s appeal to modernist strategies of shooting and cutting compensates for the city’s ambiguous modernity, and in some senses, these agents of a potential de-particularization actually put on display what is uniquely compelling about the film in question and the city it means to celebrate.

This essay deals with one example of a city symphony that, in many ways, is not so impressively or obviously modernist and that is about a city that is ambiguously modern. The city in question is Milan, and the film Stramilano, directed by Corrado D’Errico in 1929. I want to place the film in a specifically Italian context, but I hope that in doing so, the specificity of the context will illuminate some of the more general or generic concerns that seem to be typically at work or under pressure in the city symphony.

Milan’s population hovered at just around one million in the late 1920s and was substantially larger than that of Rome at that time, whose population was roughly 800,000 during the same period. Italian cities grew significantly across the 1920s, despite official state policy that sought to limit the growth of urban populations. The urban itself was a fraught subject under Fascism, which sought to embrace certain forms of technological modernity, many of which are associated with the city, while maintaining or regressively returning to the traditional values associated with rural and provincial life. The ambiguity of producing a version of modern Italy that would somehow sidestep or displace the urban reveals itself through projects such as the città nuove of the Roman Pontine Marshes.2 These were small towns built to the south of Rome that rehoused relocated working class Romans in order to deploy them as an agricultural labor force. Though the rural-agrarian pastoral imaginary governed this undertaking, a modern urbis, of modest proportions, was the result: a town form, built according to the most modern principles of Fascist architecture. Similarly, the rayon industry, which was promoted heavily by the Fascist government (and about which I will have more to say), produced a modern fabric from organic, agriculturally produced materials (cane).3 Fascist Italy’s engagement with the modern was, as I have suggested, an ambivalent affair, in which attempts to proclaim the arrival of an absolute modernity tended to coincide with some form of anti-modernism, or unintentional quaintness. Stramilano gives evidence of this conflict.

The tension between Strapaese and Stracittà exemplifies these ambivalences and bears directly on Stramilano. The terms, which loosely mean “ultra country” and “ultra city” (one could substitute “super” in place of ultra) referred to discourses current in the 1920s and 1930s which exalted the values of traditional regional cultures (Strapaese) in contradistinction to a modernist aesthetic culture, associated with urban life (Stracittà). Mino Maccari, one of the proponents of Strapaese defines it as “the bulwark against the invasion of foreign values or ways of thinking and of modernist civilization.”4 Stramilano, in its very title, clearly summons the context of these debates and locates itself on the Stracittà side of things. While the film, as we shall see, obviously celebrates urban life, its emphasis on the specificity of Milan and environs offers a version of urban living that is uniquely Italian, but not so convincingly modern(ist) in many ways. The film attempts two not entirely compatible projects: to exalt the modern city as such, while insisting on Milan as a specific, thoroughly Italian, yet thoroughly modern city.

Stramilano was produced by the Za Bum Spettacoli music hall company and distributed by Istituto LUCE, the official documentary film production agency of the Fascist government, established in 1924, only two years after the Fascists’ rise to power.5 The film’s implicit association with LUCE obliges us to some extent to read it as not just a documentary made during Fascism, but as a document of Fascism. Corrado D’Errico, the film’s director, edited and wrote for various Fascist trade and professional newspapers.6 On the subject of the documentary he wrote,

In order to be a success, the documentary must place itself outside the chronicle of everyday life and reflect the mood of the century… . It is through documentary that cinema realizes its true function as recorder of history and its tremendous responsibility, particularly in an age such as ours when the poetic ideals are brought to the highest expression.7

If we are to read Stramilano in D’Errico’s terms, then the film appears as both document and invention: the reflection of a mood.

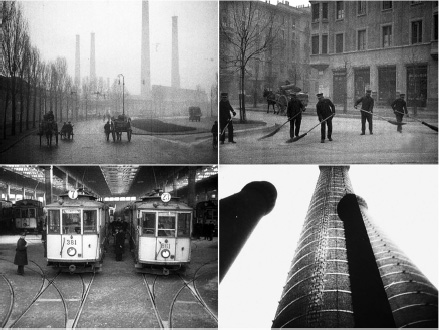

The film opens with a strong articulation of urban modernity: four tall smokestacks, or factory chimneys organize the image vertically. The tracery of the branches of denuded winter trees overlap with the chimneys to create some dialectical tension between the technological and the natural, or organic. The following shot offers a slightly off-center view of a wide urban thoroughfare with a typical row of trees planted alongside the street’s border; the same chimneys from the first shot appear in the background, scoring the morning sky, while horse- and human-drawn means of transport move unhurriedly in the bottom of the shot. In the middle of the shot, an electric street light, its lamp now turned off in the dawn light, stands vigil over the boulevard. The camera’s oblique angle vis-à-vis the factory chimneys produces a staggered and dramatic visual rhythm across the image’s horizon, however this is rhythm in stasis. The gentle pace of the traffic on the street and the fact that the means of locomotion are provided by various human and non-human animals all make this shot a highly ambivalent one and encourage us to consider the mixed nature of 1920s urban modernity: heavily industrialized, electrified, and yet still dependent on the horse and the human body as means of transportation. This shot also strongly echoes the painted cityscapes of Mario Sironi, produced throughout the 1920s, which depict the factories, new apartment blocks, tramline and rail systems that characterize the developing Italian urban landscape. Sironi’s works are specifically given titles that locate them in the urban periphery (e.g., Periferia industriale, a painting produced in 1928). The iconography of Stramilano’s opening shots, therefore, also clearly locates us in exactly these same border zones, where the most industrialized elements of the city overlap with a landscape that is not yet quite fully urban. Such spaces have been exactly where modernist practices of representation find their most fertile territory. We might think here not only of Sironi, but of the kinds of nineteenth-century French painting T.J. Clark analyses in his The Painting of Modern Life, or the work of Pier Paolo Pasolini.8

Subsquent shots—all taken from a static camera—do the work of moving us from periphery to center, and in so doing show us various forms of human labor, especially the work of street cleaners (spazzini) and those employed in loading, unloading, and selling produce at the central market. The scale of the market itself indicates synecdochically the scale of the city that we are entering, slowly. The tone or tempo throughout these first several shots could be described as rather languidly busy, and in this sense the film draws to mind the opening moments of Vertov’s Man with a Movie Camera (1929). Stramilano, however, will maintain this tempo more or less across its 15 minutes of duration.

Abruptly, following a fade out of a final image of the market, we suddenly find ourselves in a gleaming modern factory, shown to us in a panning shot, all tubes and pipes and heavy machinery, but with no humans in sight. Several more shots confirm the striking modernity of the factory that seems to await its summoning into productive activity. The film forestalls any sense of what this activity will look like by returning us to the market via shots of cows—in close up and long shot—and then to the tram shed from which, seemingly in pairs, the city’s street cars rumble out into the city. We see shots of these moving along boulevards, shots of morning commuters squeezing into the press of bodies onboard. A city awakens into life. So far then, Stramilano has introduced us to the city’s periphery and its center, its urban infrastructure, its technological modernity, and the scale of alimentary provision necessary for its inhabitants to reproduce their labor.

In what are probably the film’s most arresting and formally daring few seconds, very low angle moving shots (both tilting, it seems) of the factory chimneys described earlier are superimposed over one another in a manner that finally asserts of the dynamism of the film medium itself. As Leonardo Quaresima points out, this sequence is the film at its most modernist, and even perhaps its most Futurist, the point at which it most resembles the experiments of Walter Ruttmann’s Berlin (1927), which was without doubt an influence on D’Errico.9 The formal experimentation and dynamism of this moment are what carry us back into the factory itself—not the factory we have seen earlier, but another one, involved, it seems, in the manufacture of heavy machinery. The camera moves (panning, slightly) to track the movement of the factory machinery. We also visit another site of industrial production, a steel mill, shots of which look forward to Ruttmann’s Acciaio (Steel, 1933). Cinema’s energies are allied with and compared to Milanese industry in a mode of reciprocity.

The film then moves from the enclosed space of the factory and into the city’s center, showing us ever so briefly shots of the Piazza del Duomo, Milan’s greatest, most iconic landmark. Long and wide shots, taken, we assume, from the rooftops of tall buildings, show us other tall buildings and various forms of motorized traffic—automobiles and trams.10 Milan seems to have been not quite modern at daybreak but more fully modern by mid-morning.

Having established a basic horizon of urban modernity and having consistently allied this with the materiality of industrial production, the film then settles down to show us yet another factory in a bit more detail. This time we visit a rayon factory. Long lateral tracking shots reveal row after row of machines involved in the conversion of cane to rayon. The emphasis on rayon feels proleptic. The rayon industry was privileged under Fascism, particularly in the 1930s, following the invasion of Ethiopia in 1935 and Italy’s resultant economic isolation. Rayon could be produced in Italy from cane grown on Italian soil. Thus it was a commodity that could be produced under conditions of “autarchy,” Fascist jargon for economic autonomy. In her feminist-materialist analysis of the rayon industry during Fascism, Karen Pinkus stresses the way in which rayon was proposed as a commodity available and appropriate to every social class.11 The production of rayon was a highly dangerous and toxic affair, due to the chemicals and high temperatures needed to produce the textile, and despite official Fascist policy that discouraged or disallowed women from working in order to focus their energies on reproduction, the rayon industry maintained a largely female labor force.12 We see these productive female laborers in the tracking shots that show us the row up row of complicated machines required in spinning artificial silk from cane.13 In these shots our gaze is confronted by the gaze of these female workers who barely pause in their efforts in order to look back at the moving camera. These are some of the only extended examples of the camera’s mobility in the entire 15 minutes of the film, as well. We see the various stages of rayon’s production, which culminates in shots of the fabric issuing from the factory machinery almost like liquid metal or, more suggestively, liquid filmstrip.

Rayon touched women’s lives as both producers and consumers, and Stramilano shows us this by moving us seamlessly to a site of rayon consumption. This is a fashion show of dresses, made, we infer, from the rayon which we have just seen being fabricated. As female models slink around an art deco interior, wealthy, well-dressed women look on admiringly. One woman is shown several samples of rayon fabric by the women working in what we take to be a small fashion house. In other words, the film moves us swiftly from production to consumption. Time slows here and we, the film’s spectators, mirror the activity of the fashion show’s spectators, and because these spectators are all women, our activity of looking is also feminized. Like the visitors to the fashion house, we admire the shimmering commodities and covet the modernity they embody. The time of consumption, the film seems to say, is a time of leisure, and yet, of course, there are here bodies at work: the fashion models who move and pose so as to exhibit both the cut and feel of these dresses. What they also labor—effortlessly, it seems—to exhibit is the modern materiality of rayon itself as it clings to the body’s surface, revealingly—as if rayon were a new medium (like film) that could reveal—perhaps better than other fabrics—what a body really looks like. The languid tempo of this sequence is emblematic for Stramilano’s alternating temporality and suggests that the modern—in Italy or anywhere, perhaps—consists in periods of tediously fascinated waiting and looking.

From this scene of visual and corporeal lassitude and fascination, we move, via a very explicit intertitle that tells us where we are going, to the Teatro del Verme (Via San Giovanni sul Muro) where we will see Yia Ruskaya (Evgenija Borisenko) and the members of her school perform. Ruskaya was a refugee from the Soviet revolution who emigrated to Milan and eventually married the editor of the Corriere della Sera, Aldo Borelli. In this scene, the modernist dancer demonstrates a kind of laborious aesthetic activity: whereas ballet traditionally concealed the body’s labor, modern dance emphasizes its own effortful undertaking. The scenes of dancers performing synchronously in groups brings to mind the Fascist era spectacles of bodies performing calisthenics en masse. The film offers some impressive close-ups and one or two jump cuts that organize the material in a more charged manner, but for the most part the film is content to situate its point of view on the proceedings from what feels like the position of an audience member. The camera watches, as do we: the buzz of modern life is registered via the content of the performance, rather than the film’s form in responding to it.

That relationship of camera to the profilmic changes slightly when the film cuts to another site of consumption: a brasserie cum nightclub in which the camera responds mimetically to the rhythms of the jazz band. Extreme close-ups taken by a camera that excitedly bobs and shakes in response to the movement of musicians produce fleeting currents of synaesthetic harmony between the camera and its object of representation. The scene in the dance hall is framed with a higher degree of abstraction and plasticity than is the case elsewhere, as if the film itself had finally reached a frenzy of excitement commensurate to the life of the city it seeks to represent.

In keeping with the momentum the film seems to be enjoying at this point, it sends us off on a furious early morning car trip outside Milan to Lake Como. A slow panning shot from above the lake allows us to survey its beauty, but at the expense of introducing the outdated tempo and aesthetic of early cinema vedutismo, as if the trip outside the city immediately results in a slackening of the film’s modernity. The film remembers itself, however, and returns us via a single edit to Milan’s Stazione Centrale—in 1933, Corrado D’Erico would celebrate the musicality of train stations and railways in his Ritmi di stazione. What we see, via a high-angle long shot, is the city’s nineteenth-century station (designed by Louis-Jules Bouchot and opened in 1864), but not the new station (designed by Ulisse Stacchini) which was at the time of filming under construction and eventually opened in 1931. Next we are offered a screen split diagonally that shows us one train leaving as another departs. The film at this point nearly seems to overcompensate for having lost track of its ambitions on the short jaunt to Como, and thus seeks to over-emphasize its ability to be modern and modernist in this graphic division and multiplication of screen space.

Finally the film concludes anachronistically by returning us to a night time skyline and its flashing neon lights advertising all that could be bought and consumed in Italy in the 1920s. Conspicuous among this electric riot of signs and symbols are advertisements for Fiat, Italy’s largest car manufacturer, and Magnesia San Pellegrino, a popular cure for constipation. Somewhat unconsciously (we imagine), then, Stramilano ends by gesturing towards questions of production and consumption that one could take to be its consistent concerns, from the first shot of the factory chimneys, to those of the central market, to rayon production, to the fashion show and to this finale of frenzied neon display. Production, we have seen, is quickness, exertion, and speed; consumption, like constipation, or like the fashion show of rayon dresses, is a mode of deceleration. The film seems to have a hard time deciding between which mode it wants to emphasize. In fact, the film may be compelling us to entertain speed and slowness as two core constituent elements of (Milanese) urban modernity.

The film’s closing shots feature the Milan duomo. The penultimate shot features two irised exposures of trains moving along train tracks, with the duomo hovering behind. These double-exposed irises disappear, and we are left with only the duomo itself, that most iconic signifier of Milan. These final seconds suggest that Milan’s ancient history happily englobes its modernity: the film offers a synthesis of past and present. The dated effect of the iris (a quaint effect by this point in film history), however, lingers and mingles with the conservatism of leaving us with this final image of ecclesiastical authority. Perhaps nothing in the films feels quite as old-fashioned as this odd conclusion.

Stramilano’s charm as a historical artefact extends from what I take to be its ambivalence and awkwardness in relation to its subject: modern Milan. Presumably D’Errico’s imperative was to make Milan—and thus Italy—seem like the most modern of places. Instead, the film offers a number of the signs, indices, and experiences of modernity but in a stylistic and iconographic manner that feels oddly less than convincingly up-to-the-minute. City symphony films are always, to some extent, no matter how completely modernized the city in question might be, an advertisement for—and an assertion of—that city’s modernity. Given its emphasis in the closing few seconds on the neon signs flashing gaudily in the night sky, it seems fitting to suggest that Stramilano presents a version of modern Milan—and modern Italy—that might be more advertised than realized.14