Jan Koelinga’s involvement in avant-garde circles during the production of De Steeg (The Alley, 1932) and his relations with the Nazi film industry in the 1940s are well-known facts in the Netherlands, but less has been written on his early work, situated in the area of photography and the socialist press. De Steeg can be considered a palimpsest, hiding under its surface remnants of both social photography and avant-garde cinema. As a result, this multi-layered film answers to Agnes Petho˝ ’s concept of a parallax historiography, which

refers to the way in which earlier forms of cinema get to be revisited and re-interpreted from the perspective of newer media forms of moving images, or reversely, how these newer media forms can be interpreted from the perspective of earlier forms of cinema.1

Appropriating elements of Koelinga’s earlier photographic work, De Steeg can also be described as what Irina Rajewsky called a form of “trans-medial intermediality,” being “the appearance of a certain motif, aesthetic, or discourse across a variety of different media.”2

Koelinga’s De Steeg was the initiative of the filmmaker himself and it was distributed by De Uitkijk, the Amsterdam cinema of the Dutch Filmliga. In his dissertation Cinematic Rotterdam, Floris Paalman states that the film

shows the turn within the avant-garde towards explicit social engagement, which was extra motivated by the international financial crisis that started in October 1929. It is a shift of focus that is also recognizable in the works by people like László Moholy-Nagy, who had been a guest of the Filmliga Rotterdam shortly before.

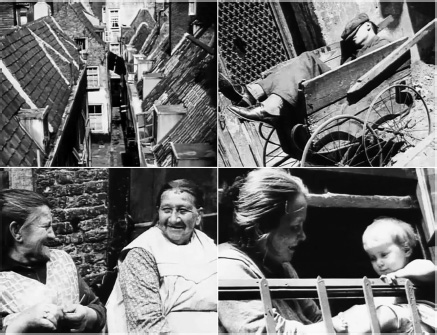

Indeed, in contrast to earlier “a-social” Dutch city symphonies such as Joris Ivens’s cine-poems De Brug (1928) and Regen (1929), De Steeg gives a characteristic image of life in the Rotterdam slums in the Depression Era. Starting with iconic images of modern and modernist Rotterdam such as the Coolsingel avenue with its luxurious department store De Bijenkorf, the camera subsequently explores the poor and destitute in the nearby slums, showing children afflicted by diseases such as scabies, a cat in a window, and a mother breast-feeding her child. From the wealthy life in the elegant center, we take a sidestep to the forgotten lower-depths of the modern metropolis, not unlike other contemporaneous city symphonies such as Moholy-Nagy’s Impressionen vom alten Marseiller Hafen (Vieux Port) (1929).3 In other scenes, De Steeg continues alternating between high and low life, e.g., in the sequence juxtaposing musicians in the park versus a street musician with an accordion, making a strong social-realist statement despite some symbolic imagery. The film’s exact location was the Schoorsteenvegersgang alley, near Hofplein. While the press conceived the film as a protest against the poverty in the Rotterdam slums, Koelinga also wanted to show the beauty in ugliness. More than just registering, Koelinga used a quite romantic representation of life in the slums as seemingly uncomplicated, straightforward, and solidary.

De Steeg premiered on 3 December 1932 at De Uitkijk. Filmliga did not only exhibit many foreign avant-garde and documentary films, it also stimulated local productions, which were often crossovers between documentary and avant-garde, such as the early works by Ivens, which, just like De Steeg, were shot with a Kinamo, the first handheld camera made in the 35mm format. At De Uitkijk, De Steeg was screened together with another avant-garde documentary, De Trekschuit (The Barge, 1932) by Otto van Neijenhoff and Mannus Franken. Dutch newspapers wrote positively about Koelinga’s debut.4 In Filmliga, the homonymous journal of the Dutch film society, Henrik Scholte called it “a splendid and strong cine-poem.”5 Chr. de Graaff, in the Amsterdam-based liberal newspaper Handelsblad, wrote,

What a famous Russian filmmaker such as Vertov only achieves by turning the world on its head and by use of all kinds of film tricks: the relentless attention to a spectacle, in which actually nothing special happens, our young compatriot manages to realize in a Rotterdam alley by just a few popular types, an accordion player, a woman at a washtub, some mothers with children, two chattering old females.6

De Graaff also praised Koelinga’s compassion and expression of joy of living, contrasting with what he called the “conventional sour ‘socialist’ vision.”7 The critic lauded Koelinga’s individualization of the masses, thus showing his humanist stance. “Koelinga, who didn’t take advantage of any intrigue, any scene, has succeeded in this almost unattainable what the French Unaminists have almost vainly sought to give in their literature. And this makes this a very rare debut!”8

Filmliga critic Menno ter Braak was more disapproving. When a sound version of the film with music by Arthur Bauer was released in May 1933, he denounced Koelinga’s symbolism, such as the park and sea motifs when the accordion is played, and advised him to stick to realism. Ter Braak made clear that the park and sea images were poetic as such, but it was the montage of them together that made them banal, serving as moral comments on the slum images. Ter Braak also thought Koelinga was too strongly influenced by Ivens’s style and should start working on his own. He complained that the camera was too restless and the editing too jerky, but explained this by Koelinga’s lack of means. Yet, he considered the film a “hors d’oeuvre” tasting for more and he liked its unsentimental focus on the alley inhabitants:

The objectivity of the camera constantly has a tragic side effect by the touching and correct way in which Koelinga records the details of life in the alley… . Thus Koelinga’s look at the human types in the slums, of which he now and then has excellently struck the mood, is without sentimentality. These are really inhabitants of the alley he filmed, not extras cockeyedly gazing into the lens in a studio setting. Especially his children’s faces are peculiarly innocent and therefore naturalistically true.9

After screenings at De Uitkijk, the Centraal Bureau voor Ligafims distributed the film to various local cinéclubs and regular theaters throughout the 1930s, often as a short preceding a feature.10 Both left-wing socialist and conservative catholic newspapers praised De Steeg, when it was screened together with Paul Fejos’s Marie: légende hongroise (1932) about the downfall of pregnant housemaid.11 De Steeg was also included in a program of avant-garde documentaries at the Antwerp conference of the Catholic Film Center in 1933.12

Despite the favorable reviews of De Steeg, Koelinga’s career did not develop as film projects stranded.13 However, Koelinga did shot memorable footage of the Depression era such as police putting down riots in the Amsterdam Jordaan quarter—images that heavily contrasted with the idyllic image of the quarter in Dutch fiction films at the time. Koelinga was also one of the cameramen of the 1934 avant-garde spy story Blokkade by Willem van der Hoog, a not too successful attempt by Filmliga members to make a fiction film that was halfway between mainstream and avant-garde. Disappointed because of the Depression and the lack of Dutch governmental support, the desperate Koelinga accepted an offer by UFA in the early 1940s to take shots in the Netherlands—some of which would be inserted in the anti- Semitic propaganda film Der ewige Jude (Fritz Hippler, 1941). Koelinga always claimed he did not know about this, though he also continued working for UFA during the war, producing anti-Allies comical shorts among others.14

Shortly after the war, Koelinga was interned for several months and he could not work for three years, not getting any state commissions while most documentary filmmakers were dependent on subvention. He did manage to make a handful films in the post-war era, though local and national authorities kept making his life difficult. In a 1973 Dutch TV documentary, Koelinga was bitter about the way the Dutch government had treated him and about others who had been much more active in Nazi propaganda. After the May 1940 German bombing of Rotterdam, Koelinga had shot the ruins on behalf of the Germans, not intended for commercial use but for documentation. According to Floris Paalman, Koelinga’s Verwoestingen in Rotterdam (Destructions in Rotterdam, 1940) shows

people strolling through the city, watching the remnants that have almost become an ‘attraction.’ Different from most static recordings by others, Koelinga made use of all kinds of mobile framing, including overview shots taken from a train. These well-made and unique images have long been left unconsidered. The reason might be that Koelinga moved from a socialist engagement towards national-socialist sympathies, which caused him to collaborate on various pro-German propaganda films, although that was not yet at issue in this case.15

After the war, many inhabitants of Rotterdam as well as broadcasting companies were eager to view this material over and again, but resistance organizations kept Koelinga’s dark past alive to prevent screenings. Koelinga’s reputation of a contaminated film director also affected projections of De Steeg, even though it was shot several years before his involvement with Ufa. Koelinga remained rather poor and only in 1982, when the German television showed De Steeg, he finally made some money.16

Paalman points out that Koelinga had accompanied the first screenings of De Steeg with photo collages on display in the cinema theater. In his review of the 1933 sound version, Menno ter Braak mentions that ten photomontages by Koelinga were exhibited at the Rotterdam cinema Lumière, during screenings of De Steeg.17 It isn’t exactly clear what kind of photos were shown but it is quite likely that there was a relationship between Koelinga’s filmic debut and his earlier photographic work. After having worked for some years as a sales agent in the mid-1920s, Koelinga had become a photographer for Voorwaarts, the social-democrat daily for Rotterdam and surroundings. On behalf of Voorwaarts, journalist Herman van Dijkhuizen published in 1926 a special issue, entitled De Rotterdamsche roofholen en hun bevolking (Rotterdam’s Robber Dens and their Population), subtitled “Peregrinations of a Voorwaarts editor through the neighborhoods of Rotterdam, where prostitution and crime are rampant.” First included in Voorwaarts, the text was later published as a separate book in several reprints.18 To give the publication prestige, a foreword by substitute prosecutor Mr. C.F.J. Gombault was added. Van Dijkhuizen’s book was a virulent pamphlet against usurers, pimps, prostitution and the extortion of women, forcing them to work in prostitution, the deliberate poor housing related to this, and the robbing of clients. The text ended with a plea to authorities to take action. While Van Dijkhuizen had noble intentions, the booklet though led to a court case. Two ladies working in the so-called Deli-Bar on Katendrecht, a typical low-life area of Rotterdam, had protested against their picture being printed in the publication. They sued the editor in chief of Voorwaarts, who, after a first appeal, was judged to a fine, as the young photographer had taken their picture under false pretenses. As Koelinga was at that time the only photographer in the service of Voorwaarts, it is safe to conclude that the (sometimes heavily retouched) photographs of slums, prostitutes, and pimps in the publication are all his, even though the booklet does not mention him. Apparently, Koelinga’s interest in the literally dark side of the city already existed when making these photographs. From the slums of Voorwaarts to the alley of De Steeg is not such a big step.

However, Koelinga’s intentions with De Steeg are not clear. He surely did not use it to better the situation of crime and prostitution, as had been the goal and also the effect of Van Dijkhuizen’s booklet: better housing started in Dutch main cities in the 1920s on a large scale, even if not for everybody’s purse. It is generally accepted that most social housing projects in big cities such as Hendrik Petrus Berlage’s development plan for Amsterdam were beneficial mostly to lower middle classes, but not below this level, like the inhabitants of Koelinga’s slums. Moreover, Koelinga’s film differs stylistically from his earlier photographic works. His photography for De Rotterdamsche roofholen en hun bevolking had been pretty straightforward and is not marked by any unusual angles. People were mostly photographed “en face” or “en profil,” either full length, half-sized, or up to the knee. Overviews of streets were often in diagonals to show depth, and often shot on eye-level. That all changes with De Steeg, in which style becomes a highly important ingredient, as indicated by unusual camera angles, the increased use of close ups, and avant-garde-like editing. It is clearly inspired by French Impressionist filmmakers or the innovative editing and cinematography of the Dutch film Handelsbladfilm (Cor Aafjes, 1927), which was shown at the Paris art house Studio des Ursulines. In short, for Koelinga, form becomes important in De Steeg.

The improvement of the 1920s modernist architecture shown briefly at the beginning of De Steeg is still out of reach for the lower classes, Koelinga seems to say—even when he does not show housing but shops. On a meta-level, we might say this denial for improvement applies to Koelinga himself. In the February 1933 issue of Ons Eigen Tijdschrift, critic Van Melrose positively overviews young Dutch art cinema, but at the same time regrets that so many filmmakers, Koelinga included, are not getting more opportunities.19 The complaint was typical for its time, as the international avant-garde had a hard time because of the polarization and politicization of society, the costly introduction of sound cinema, and the loss of the primacy of the image. Moreover, while Dutch public financing was minimal, Dutch private financiers rather preferred to invest in film exhibition, film technology, and mainstream feature films.20 In March 1934, Koelinga was one of the signatories of a manifesto in Filmliga, proposing to help to rebuild the Dutch film industry, albeit with room for artistic experiment. Yet the Dutch trade association NBB, which owned Dutch film production to a large extent, focused on entertainment and thought artistic experiments too expensive. According to Ansje van Beusekom, “The crisis made the grapes extra sour and some filmmakers and critics, who rather preferred a new national cinema by the avant-garde filmmakers than the frivolous films being produced, reacted extremely vindictively to these developments.”21