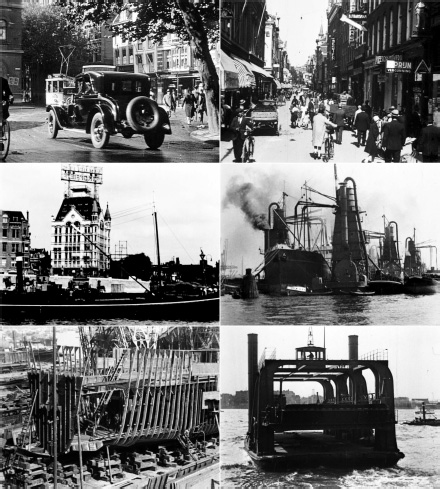

Figure 10.1 De stad die nooit rust (Friedrich von Maydell and Andor von Barsy, 1928)

Apart from a few short references by Dutch film historians in the 1980s, De Stad die Nooit Rust (The City that Never Rests, 1928) by Friedrich von Maydell and Andor von Barsy has been an overlooked film.2 Only recently, in his study of Cinematic Rotterdam, Floris Paalman gave an in-depth account of its production history, an endeavor that also resulted in a full restoration of this substantial and significant city symphony in 2010.3 The City that Never Rests is a film about Rotterdam, which had transformed from a small town in the 1850s to a colossal industrial port city in the early twentieth century. Moreover, local administrators, press, and artists presented the city in a much more modern way than it actually was at the time.4 Likewise, The City that Never Rests evokes a vivid metropolis with busy streets, bridges, canals, and markets, before moving gradually from the smaller inner harbors to the enormous outer seaport, shown in its different sections and manifold activities.5

The film is almost an hour long, and it was made by the German Friedrich von Maydell (1899–1938) and the Hungarian Andor von Barsy (1899–1965) for the Rotterdam-based production company Transfilma.6 Von Maydell had established Transfilma in 1927 and Von Barsy was the company’s cameraman. Even though Von Maydell was officially credited as the director of the film in the opening titles and the original list of title cards, the film is usually attributed to Von Barsy due to his outstanding cinematography. Before shooting The City that Never Rests, he and Transfilma had already made several films for industrial companies and for the municipality of Rotterdam. Later, Von Barsy worked, among others, on Leni Riefenstahl’s Olympia (1938) and was awarded prizes for best cinematography at the film festivals in Venice and Berlin.7 In 1929, he also made Hoogstraat, which can be described as a small city symphony dealing with Rotterdam’s main shopping street.

At the time of the film’s release, the press described The City that Never Rests in close connection with the city symphony phenomenon, echoing the filmmakers’ intentions. In the early stages of the production, the film’s working title was Rotterdam: Symphonie van den Arbeid (Rotterdam: Symphony of Labor). This underlined Transfilma’s ambitious plan to make an equivalent to Walther Ruttmann’s Berlin: Die Sinfonie der Grosstadt (1927) or to compose “a little sister” of the Berlin portrait: “een Rotterdamsche filmsymphonie.”8 According to Von Maydell, the film should be defined by tempo and should become strongly rhythmic; no shot should be longer than five meters of film so that the tempo would be even more brisk than the one Ruttmann featured in Berlin.9 However, in the process, the direct city symphony references in the film’s title disappeared. While the filmmakers had already started filming, Transfilma approached the municipality for sponsorship and the film turned into a commissioned production, planned as a jubilee film for the 600th anniversary of Rotterdam. This was accompanied by a change of title: Van Visschersdorp tot Wereldhavenstad (From Fishing Village to World Port City), which after the premiere was replaced again by The City that Never Rests.10

In The City that Never Rests, the modern and industrial big-city imagery typical for city symphonies is strongly connected to the predominant role the port plays in the film. Roughly speaking, the film can be divided into two parts: The first quarter depicts the city center whereas the second, much longer part, concentrates on the harbor. The port is represented as being one of the biggest and most important in the world with its endless parade of ships, dockyards, factories, silos, and all kinds of modern technology for loading and unloading masses of goods such as cranes, elevators, and conveyor belts. The camera focuses on details of machines, such as shovels, pipes, and claws, and on their movements. Special attention is paid to the ferryboat on the river Maas and the railroad lift bridge “De Hef” (The Lift). Built between 1925 and 1927, “De Hef” immediately became an icon of modern engineering and, in 1928, Joris Ivens also paid tribute to it with his film De Brug (The Bridge). In line with a Futurist and Constructivist fascination with the dynamics of machinery and fast-paced city life, The City that Never Rests celebrates the functional architecture of the harbor, underlining Rotterdam’s industrial modernity and metropolitan character as a global port city.

The first part of the film, dedicated to the city center, also shows imagery of moving machinery and modern urban life, containing shots of the arrival in the city by train, crowded shopping streets, bridges with all kinds of modern traffic, billboards, the Waalhaven airport, Rotterdam’s skyscraper “Het Witte Huis” (The White House), and the modern Coolsingel boulevard. A critic of the time described the scenes as “an explosion of technical force,”11 while another one summarized the portrayal of Rotterdam as “a life song of the modern big city.”12 However, the film also contains shots that present Rotterdam as a smaller, pre-industrial city: a picturesque canal with historical warehouses, an old-fashioned windmill in the Delfshaven, children playing in a courtyard. Like most city symphonies, The City that Never Rests emphasizes disjunctions and dichotomies characterizing modern metropolitan life, such as big versus small, poor versus rich, new versus old, countryside versus city. In The City that Never Rests, though, the pictures of the older city and playing children are not only there to heighten the impact of the modern urban-industrial imagery, they are presented as being essential aspects of the city of Rotterdam. This is not a new city, the film insists, like Chicago, New York, or even Berlin, this is a city with a history, one that has been an industrial and maritime force for quite some time, a city with traditions and regional significance. This parallels with Marlite Halbertsma and Patricia van Ulzen’s remark about interwar Rotterdam: “Opposite the city striving for progress, there was a Rotterdam that was not modern and dynamic at all. The old and new Rotterdam were interwoven.”13

Compared with other city symphonies marked by a high degree of abstraction and the pursuit of a purely visual film language, The City that Never Rests features an unusually great number of intertitles (almost 20 percent of the film), making the film profoundly expository.14 Many of the 62 intertitles identify a specific location and link the succeeding shots with historical facts, a function of the displayed site, a particular port activity, or with Rotterdam’s modernity, metropolitan character, and international importance. In so doing, the title cards determine the interpretation of the images, promoting Rotterdam as a world port city and underlining the city’s identity and uniqueness. In addition, together with aerial views and numerous (animated) maps, they clarify the city’s different expansion phases. As devices of spatial orientation, these aerial views and maps show the viewer the exact position of the displayed sites within the greater cityscape.

The extensive use of intertitles is considered uncommon for city symphonies. Referring to Ruttmann’s Berlin and Dziga Vertov’s Man with a Movie Camera (1929) as prototypes, Alexander Graf points out that these films often “display an almost total suppression of intertitles.”15 However, this is certainly not always the case as Jesse Shapins has demonstrated in his analysis of Mikhail Kaufman and Ilya Kopalin’s Moscow (1926), in which intertitles “create a filmic map of Moscow, guiding the spectator through the distinct spaces, pointing out the city’s important monuments, political representatives, and municipal achievements.”16 Like Moscow, The City that Never Rests privileges “architectural and geographic specificity over abstract spatial representation.”17 Through its particular use of title cards in combination with its visual material, it represents Rotterdam in its very own nature as a unique and specific city.18

As Graf describes, city symphonies are characterized by a rhythmic and associative montage, representing “the pace and rhythm of urban life expressed through editing techniques.”19 They internalize the rhythm of the city as their structuring principle instead of dealing with the modern city purely on a pictorial level. The City that Never Rests shows a dynamic montage style that I would like to describe as a flow. The editing in general is rather even and calm insofar as length and tempo are concerned. Shots succeed each other in a relatively constant manner and the film is not extremely fast-paced. Its average shot length is 6.9 seconds, whereas that of Berlin is almost half as long, at 3.5 seconds, and Man with a Movie Camera only a mere 2.3 seconds.20

The flow is also supported by the discreet use of associative montage. Instead of juxtaposing contrasting phenomena, the editing pattern is first and foremost based on a series of connecting images. In this regard, the film follows Pudovkin’s idea of linkage rather than Eisenstein’s montage of attractions. An example is a sequence of shots of traffic intersections in the city center, where the shape of 90-degree corners and the corresponding direction of movement connect different street spaces. In the first shot the audience is provided with a high camera position, and we see a junction with trams crossing. The next shot shows another intersection with trams passing at a right angle from a similar position, followed by a shot of a third junction at street level where a tram has just turned the corner. We are now introduced to the street at ground level via the shape of 90-degree corners and trams, so that the next shot of a street without trams and rails is linked fluently to the previous ones. Another example of the film’s associative montage is the loading and unloading of goods in the harbor and the repeated downward and upward movements between the docks and the decks. Even though these are diametrically opposite movements, in The City that Never Rests they become part of the same flowing motion.

Rather than based on editing patterns, the film’s dynamic style—there is hardly a static shot in The City that Never Rests—mainly relates to motion within the images showing traffic, people, ships, machines, and goods in motion, steam, and the endlessly moving water of the harbor, canals, and the sea.21 In addition, the dynamic style is also the result of the panning and travelling camera, often placed on a ship or vehicle. All these movements are equally paced. There is no extremely fast motion but a continuous flow of atmospheric images. A certain rhythm or alternation in tempi arises from the density of motion and directions of movement within the frame and the change of these movements between shots. In this regard, one could say that the film starts with an allegro movement, which captures the rapid development of Rotterdam from the age of water and reed, to “the age of rapid transit”22 and the images of a fast-moving train. After arriving in the city, the tempo slows down into a flowing andante throughout the rest of the film. Within this flow, there are again a few shots of a slightly faster motion such as images of waves that briefly speed up the tempo. The intertitles, on the other hand, slow down the tempo in regular intervals. This flow corresponds to the rhythm of a port city as it represents and internalizes the flowing-waving movement of the sea, water, and ships—in combination with urban motion.23 Therefore, the specificity of Rotterdam is also addressed on the level of its montage. In addition, this flowing rhythm distinguishes the film from the city symphonies Berlin and Man with a Movie Camera, with their representation of a hectic city pulse as a quick succession of contrasting impressions.24 Its flowing rhythm, however, answers perfectly to John Grierson’s notion of “the symphonic form” in film:

The symphonic form is concerned with the orchestration of movement. It sees the screen in terms of flow and does not permit the flow to be broken. Episodes and events, if they are included in the action, are integrated in the flow. The symphonic form also tends to organize the flow in terms of different movements, e.g. movement for dawn, movement for men coming to work, movement for factories in full swing, etc., etc.25

In short, The City that Never Rests employs a modern big-city imagery that is characteristic for many city symphonies. Rotterdam is portrayed as a modern global port city with metropolitan features. In this regard, Rotterdam is represented as bigger and more metropolitan than it actually was, with its rather limited size and half a million inhabitants in the 1920s and 1930s. The big-city features, however, also allow for the presence of small-scale and pre-modern elements that coexist with the metropolitan ones as two parallel aspects of the city, emphasizing the city’s history and tradition. Moreover, in the combination of photographic material with intertitles and maps, Rotterdam is represented in its geographical, historical, and economical specificity. This peculiarity is also emphasized structurally on the level of the montage, particularly through the slower-paced and flowing rhythm that corresponds to the pulse of a port city that also includes smaller harbors and village-like surroundings.

The hybrid character of The City that Never Rests, oscillating between promotional film, documentary, and city symphony, could explain why the film has been absent from the discourse on city symphonies.26 However, there is another reason for this neglect, which is related to the film’s own exhibition history. After its premiere on 15 August 1928, the film underwent numerous changes that resulted in various shortened release versions, often not exceeding half of the original’s length.27 In these versions (some of them also including supplementary new shots), the sequences dedicated to the city center were cut out, reducing Rotterdam almost exclusively to the port. As a result, the film became rather a promotion film for the Rotterdam harbor than a city film. Moreover, due to the constant re-editing and re-use of the images in multiple versions, the original premiere version became completely inaccessible. The only traces left were shortened and fragmented elements that made their way to the archives of the EYE Filmmuseum and the Netherlands Institute for Sound and Vision. The original city symphony, however, was lost until the restoration in 2010 by EYE and the Municipal Archive of Rotterdam. This attempt to reconstruct the original premiere version out of the surviving pieces made the city symphony accessible again to scholars, historians, and audiences.28