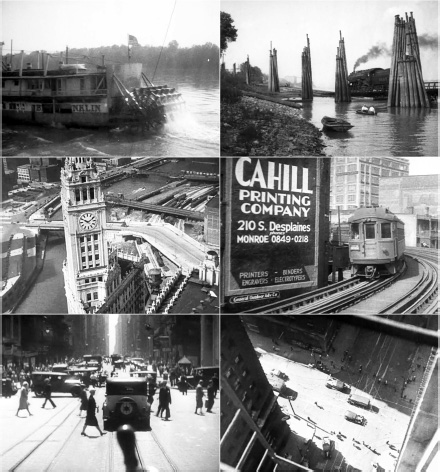

Figure 11.1 Weltstadt in Flegeljahren: Ein Bericht über Chicago (Heinrich Hauser, 1931)

In the spring and summer of 1931, Heinrich Hauser (1901–55) made a car trip through the United States, which resulted in his book Feldwege nach Chicago (Dirt Tracks to Chicago) as well as in his silent documentary feature Weltstadt in Flegeljahren: Ein Bericht über Chicago (literally World City in Its Teens: A Reportage on Chicago, also translated as Chicago: A World City Stretches Its Wings).1 While the film focuses on Chicago, the book covers his entire journey. A sailor, soldier, miner, medical student, steel worker, engineer, farmer, pilot as well as a writer, ghostwriter, translator, traveler, photographer, and journalist, Hauser was considered an outsider to the professional world of cinema.2 In the Berliner Börsen-Zeitung, for instance, Fritz Olimsky wrote that Weltstadt in Flegeljahren was “not a product of the proper film industry” but that it was a “film reportage of an outsider, the writer Heinrich Hauser,” which “broadened one’s horizon by miles.”3 Likewise, in Die neue Rundschau, Siegfried Kracauer noted that it was Hauser’s independence from the film industry that determined the freshness of his film, which was not concerned with the “disputable demands of distribution,” but which simply recorded “what good eyes could see.”4

For his contemporaries, Hauser was first and foremost a journalist working for various papers including the Frankfurter Zeitung and a prolific writer of novels, science fiction, travel and photo books. His first novel Das zwanzigste Jahr (The Twentieth Year) was published in 1925 and for his 1928 novel Brackwasser (published in English as Bitter Waters), he received the prestigious Gerhart-Hauptmann Prize.5 He consequently acquired some fame as “a filming writer” or “an auteur-amateur filmmaker.”6 Apart from Weltstadt in Flegeljahren his cinematic oeuvre consists of a handful of other films, including the successful “Kulturfilm” Die letzten Segelschiffe (The Last Sailing Ships, 1930), which was distributed, like the Chicago film, by Naturfilm Hubert Schonger.7 Together with his friend and writer Liam O’Flaherty, Hauser also made a film on the Aran Islands, six years before Robert Flaherty made Man of Aran (1934).8

Hauser would eventually become a geographical outsider as well. In 1938 he emigrated voluntarily to the United States.9 After the war, he returned to Germany, where he worked for the weekly Der Stern but he never felt at home again. Unable to acquire a new visa to return to America, he was psychologically and literally stuck “between two worlds.” This phrase evidently held great poignancy for Hauser—he himself had used these very words as a title for one of his manuscripts as well as for the first paragraph of the preface to Feldwege nach Chicago.10

Finally, Weltstadt in Flegeljahren itself can be considered an outsider film as it was rejected as an educational film by the Film Department of the Institute for Education (Bildstelle des Zentralinstituts für Erziehung und Unterricht) due to accusations that it was confusing and chaotic. Because of this negative pronouncement, which was strongly objected to by Rudolf Arnheim, among others, Weltstadt in Flegeljahren received very poor distribution and was hardly screened in regular theaters.11 Consequently, despite some very positive reviews, the film fell into oblivion soon after its October 1931 premiere at the Alhambra theater in Berlin. For many decades, the film was even considered lost. In 1984, the original nitrate negative was discovered at the Bundesarchiv Filmarchiv in Koblenz as part of the Naturfilm Hubert Schonger film collection, where it was restored in 1993.12 In addition, a nitrate print with Dutch intertitles, which originated in the distribution collection of the Dutch Filmliga, was restored in 1990 by the Netherlands Filmmuseum (today EYE Filmmuseum). As a result, only recently German scholars have rehabilitated the film and connected it to the city symphony phenomenon of the interwar years.13

Lasting 74 minutes in total, Weltstadt in Flegeljahren consists of five acts, in which Hauser draws attention to the specificities of Chicago, including its architecture, skyscrapers and skyline, the Loop, its views along the Chicago River, and its industry.14 Intertitles play an important role as they identify the images directly as parts of Chicago. The Loop, for example, is described as “the blustering heart of Chicago.” Showing the Mississippi River and life on and along the river, Act I is comparable to the opening scenes illustrating the arrival in the city that appear in many city symphonies. Hauser takes an almost ritual approach to Chicago via the Mississippi River, which, of course, does not run through Chicago, or even near it, passing roughly 150 miles to the west of the city. Taking almost a quarter of an hour, the film’s first act gradually shows the transition from rural life and manual labor (farmers harvesting hay, life on a river steamboat) to mechanized labor and modern life in the industrial metropolis. Visualizing the actual arrival in the city, Act II opens with a series of panoramic shots showing the city’s skyline, followed by various long shots using a closer perspective. Combining shots taken at street level with those taken from skyscrapers, Hauser explores the impressive architecture of Chicago as well as its busy streets filled with crowds and motorized traffic, including the elevated railway that is such an integral element of The Loop. Act III continues this exploration of the city but shifts its focus to labor: office work, assembly lines in factories, port activities, construction sites, and the meat producing and packing industry. Focusing on street life, particularly on Madison Avenue and the Jewish market on Maxwell Street, Act IV combines footage of children playing in the streets with images of urban poverty: the slums hidden behind the skyscrapers, unemployed men, homeless people, and a drunken man poisoned with car antifreeze. Act V finally is dedicated to leisure: sports activities in parks, the Riverview Amusement Park, and life at Lake Michigan.

By means of these five acts, Hauser constructs a comprehensive “cross-section” of Chicago without using the typical style of montage associated with this concept. As Michael Cowan has explained, the term Querschnittfilm (“cross-section film”) was originally used in the late 1920s for archival compilation films before it became associated with experimental and documentary films such as Ruttmann’s Berlin.15 Antje Ehmann emphasizes that while Hauser’s film does not adhere to the conventions of the cross-section concept, it still establishes a complex portrait of 1931 Chicago by means of an accumulation of detailed observations.16 Indeed, it is primarily because of its diversity and not so much because of its montage technique that Weltstadt in Flegeljahren evokes the scale and multiplicity of Chicago. In contrast to Ruttmann’s experimental, rhythmic, and associative editing, Hauser’s montage is instead additive or enumerative: traffic policemen conduct masses of cars, a street vendor sells pencils, office clerks work on their typewriters, bananas pass on a conveyor belt in the harbor, skyscrapers are under construction, bridges open and close, and a man gives a speech about Soviet Russia to a huge crowd of bystanders in a park monitored by baton-wielding cops. Hauser’s observational style can be compared with a succession of moving photographs—framed images layered with different depths and elements in the fore- and background. With their inner-frame montage, some of these images are very powerful, such as the shot of an enormous parking lot in front of the city’s skyline that follows shots of endless streams of cars entering the city, anticipating similar sequences in Ralph Steiner and Willard Van Dyke’s The City (1939) by nearly a decade. Another example is the highly ironic, almost surreal shot of unemployed men lying on the grass in Grant Park with the heroic statue of General John Logan behind them and the towers of the Stevens Hotel looming in the background. However, at other times, as also Ehmann acknowledges, Hauser’s film does resemble a cross-section film in the style of Berlin. Ehmann refers to the market sequence in Act IV, which she labels as “querschnitthaft” (“cross-section like”) and which evokes Wilfried Basse’s Markt in Berlin (1929). Similarly, she mentions the beach sequence in Act V that is reminiscent of Ruttmann and Vertov.17 Both sequences present their subject matter by a cross-sectional montage of market respectively beach impressions: Market stands are intercut with street vendors, customers, goods, and street performers whereas bathing people are intercut with men and women sleeping at the beach, a man distributing books, a pretzel vendor, and various beach games. Moreover, Weltstatdt in Flegeljahren is loosely marked by the day-in-the-life-of-the-city structure, typical of cross-section city films. First, we see an empty city, people on their way to work, and morning routines such as shop window cleaning. Similarly, labor dominates the middle part of the film whereas leisure and popular entertainment such as baseball and amusement park rides are featured towards the end of the film.

In Weimar Germany, modernity was considered by many to be a specifically American phenomenon.18 This identification of the US with rationalization, mechanization, and the metropolis was developed to a large extent without drawing upon empirical research.19 Numerous European intellectuals discussing modern phenomena and America had never actually crossed the Atlantic. In his September 1925 newspaper article entitled Amerikanismus, Rudolf Kayser summed up this development:

Americanism is the new European catchword… . Trusts, highrises, traffic officers, film, technical wonders, jazz bands, boxing, magazines, and management. Is that America? Perhaps. Since I have never been there, I can make no judgment.20

According to Frank Becker, “the country across the Atlantic was solely the geographical peg for a discourse that started revolving around the pros and cons of modernization.”21 However, some writers, artists, and architects based their vision of American modernity on their own travel experiences. Both filmmaker Fritz Lang and architect Erich Mendelsohn, for instance, visited the United States in 1924. Lang processed his impressions of the nocturnal New York skyline in Metropolis (1927) while Mendelsohn documented his trip in his photo book Amerika: Bilderbuch eines Architekten (1926).22

With his illustrated book Feldwege nach Chicago and his film Weltstadt in Flegeljahren, Heinrich Hauser can be situated in the context of this debate on Americanism. Although he draws attention to the peculiarities of Chicago’s topography and inhabitants, Weltstadt in Flegeljahren is also a reflection on modernity, the American city, and the United States. In the preface to his book, at the very beginning of his journey on board of an ocean liner, Hauser describes the objective of his travels. For Hauser, America seems a country with only straight roads and orthogonally organized cities. There seem to be no deviations—either on the map, on the actual ground, or in the people’s minds. However, he does not really believe in this vision of America and therefore sets out to find its dirt roads and back alleys.23 In other words, Hauser aimed to dispel the myth of America as it had been constructed by German intellectuals.

Nevertheless, in his book and film, he creates an image of America in his turn. In Weltstadt in Flegeljahren, this picture is condensed in Chicago and the Mississippi River.24 Chicago certainly seems to answer to Hauser’s preconceptions of America as a world marked by straight lines as he depicts the vertical city with its high-rise structures as well as the horizontal grid dominated by crowds and car traffic.25 A striking detail is the Coca-Cola sign that reappears at several points during the film, presenting the city as having been inscribed by consumerism. Hauser’s emphatic attention to mechanized work, efficiency, rationalization, and the assembly line reveal a fascination with the doctrines of Fordism and Taylorism, which were widely discussed elements of the European discourse on Americanism at the time.26 Hauser’s take on this subject matter is not merely enthusiastic—it underlines disparities, labor issues, and destitution.

By focusing extensively on the Mississippi at the beginning of the film, Hauser situates the city in a broader spatial context not unlike many other city symphonies. In so doing, the city of Chicago as an emblem of a modernized, industrialized, and progressive America is linked to a Mark Twain/Huckleberry Finn adventurous idea of America through a rather romantic image of the Mississippi River with its wheel steamers.27 The journey to Chicago via the Mississippi visualizes the urbanization of nature, which is emblematic for the project of modernity. This theme of an on-going urbanization reappears in Act III when the camera depicts cranes and excavator shovels and intertitles explain: “The dinosaurs of our modern time … destroy all fields and landscapes.” Moreover, this extensive Mississippi prologue also evokes the Great Migration, which channeled thousands upon thousands of African-Americans from the Deep South to the streets of Chicago—later in the film, Hauser’s camera focuses on African-Americans and their function in the economic and social structure of Chicago. In so doing, the film is a remarkable and fascinating study of the place of African-Americans in American society of the early 1930s. It highlights hierarchies of class and race, suggesting a Jim Crow America without stating so outright.

However, Hauser looks at this from the viewpoint of an outsider for whom Chicago and its multicolored population is somewhat exotic. His drive is first and foremost his unstoppable curiosity for a world unknown to him. This curiosity also concerns the depiction of different social and ethnic groups, presenting American society as diverse and multi-ethnic. In so doing, Hauser’s cross-section also includes a sample of city dwellers, playing on the contrast between rich and poor. Some of these images might feel disturbing but Hauser integrates them in his enumerating and observational way of filmmaking. Undeniably, an element of voyeurism and exoticism is at stake, making more explicit his position of an outsider. In this regard, he shows squirrels in a park just as he films different ethnic groups, including Jews, African-Americans, and European immigrants. Weltstadt in Flegeljahren speaks of his desire to literally show everything, adding and piling up as many facets as possible. Hauser is clearly fascinated by the new and unknown of Chicago, which he describes as “the most beautiful city of the world … anticipating the future of civilization.”28 As Ehmann writes, Hauser’s style is mainly observational, clearly different from the more formalistic and artistic approach used by Ruttmann in Berlin.29

Weltstadt in Flegeljahren also contains a powerful critique of America and modernity, something that was picked up by critics at the time of the film’s release and that distinguishes Hauser’s work from other city symphonies. It was generally valued as a film with a social responsibility, showing sharp and honest images of real life, of the common man in the streets, and of the real America in contrast to Hollywood. Hans Taussig, for example, wrote in the Reichsfilmblatt in October 1931:

Many city films have made their way into the cinema, good and bad ones, wrong and right ones, staged and factual ones, as propaganda or for charitable purposes. City films that did not allow the audience to stop yawning… . For the very first time in the history of the Kulturfilm and the city film, this film shows a city as it really is—namely from its negative side, without ignoring the positive side either. This film deserves special appreciation.30

An example of Hauser’s critical stance is the already mentioned urbanization of nature, in an intertitle described as “the destruction of the landscape.” Another example concerns mechanized work in Act III and a sequence shot at the assembly line of the tractor factory of the International Harvester Company. “Where are the people?,” an intertitle asks. In Act IV, Hauser turns to unemployment, poverty, alcoholism, and crime, highlighting the negative effects of mechanized work and the modern American metropolis, marked by the devastation of the Great Depression. The last two acts could even be put under the titles “estrangement” and “escapism.” Act IV includes the most explicit critique and one of the strongest parts of the entire film. While images of unemployed men waiting in front of labor agencies powerfully speak for themselves, Hauser adds a sequence in which he makes use of parallel and associative editing, intercutting car wrecks with unemployed and homeless men. An intertitle underlines the visual statement: “Wrecks of society.” Nonetheless, Hauser ends on a more positive note as the last shots show smiling and waving children.31

In conclusion, Hauser’s image of America and Chicago in Weltstadt in Flegeljahren is highly ambivalent. On the one hand, it is the image of an outsider spurred by fascination, curiosity, and captivation. On the other hand, it is marked by a certain fear and vehement criticism. Hauser’s film combines a topographical approach to the city—and its cross-section—with a critical reflection on the downsides of modernity and America. In so doing, the film can be seen as part of the broader cultural phenomenon of Americanism in Weimar Germany, hovering between fascination and fear, curiosity and critique, enthusiasm and reservation.