Figure 12.1 Street Signs in Halsted Street (Conrad Friberg, 1934)

Shot in Chicago around 1934, at the height of the Great Depression, Halsted Street belongs to the underappreciated genre of the amateur film.1 The film’s opening credits link it to the Chicago Film and Photo League, a popular front leftist organization.2 The credits attribute the film to “Conrad,” who has been identified as Conrad Friberg (who also used the pseudonym Conrad O. Nelson). In spite of its relative obscurity, I believe Halsted Street offers one of the most original approaches to the urban documentary in the era before World War II. Friberg had almost certainly seen Ruttmann’s Berlin (1927) and Vertov’s Man with a Movie Camera (1929), and possibly some other city symphonies. The genre’s style of montage based on associations and contrasts shaped the shot-to-shot relations of Halsted Street and the direct street cinematography of Mikhail Kauffman and Karl Freund (the cameramen of Vertov’s and Ruttmann’s film respectively) inspired Conrad (even if his 16mm shooting lacks some of the technical elegance demonstrated by the more experienced and better equipped 35mm cameramen).

Halsted Street offers a unique approach to urban geography by following the course of Halsted Street, a major western Chicago thoroughfare from “the City Limits At the Southern End to Lake Michigan On the North,” as one of the film’s opening subtitles explains. Halsted Street shares the specificity of a single street with Hoogstraat (Andor von Barsy, 1930), but there is more to the Chicago film precisely due to the length and variety of this extensive street. A subtitle in the film announces “This Film Presents a Cross Section of Chicago As Seen On Halsted Street” immediately relating it to the Querschnittfilms, or “cross-section” films of the Weimar era. In other words, this is not simply a film of a specific Chicago avenue but also a film of Chicago using the street to literally cut through the metropolis. Thus, in contrast to the spatial freedom of cutting in Berlin and its web-like montage of simultaneous contrasts and comparisons, Halsted Street traces a cross-section of urban space and thereby preserves its spatial order. The film follows the structure of the city, rather than dissolving it.

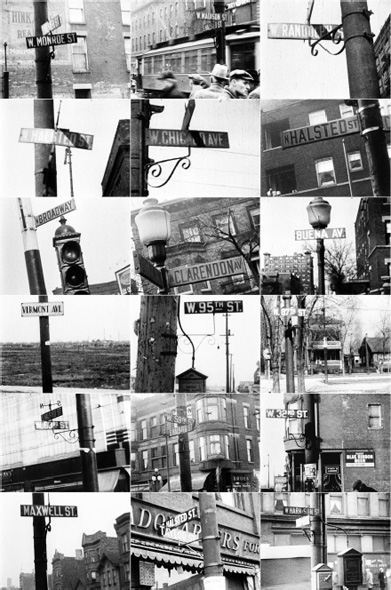

Specificity of location organizes Halsted Street, so that the viewer always knows precisely where one is along the route, as the film moves from the southern beginning of the street in the country to its northern limit in Chicago’s North Side. After opening with a street sign proclaiming “S. Halsted St,” the film’s second shot shows a farmer and his horses plowing a field. Showing how a city’s limit abuts on the country, tracing a furrow also introduces the theme of a linear pathway as well as the importance of a progressive trajectory in the film. While many city symphonies immerse the viewer in a dizzying sense that they could be anywhere within the city, Halsted Street charts a steady course in which the progress along the grid of urban streets always marks an exact position. Instead of a swirl of echoing and contrasting gestures, Halsted Street delivers a cartographic orientation, marking the film’s journey through a plethora of written signs. Like a foot-weary urban pedestrian, the film continually notes the succession of street signs: Vermont Ave.; 127 St.; 95th St.; 67th St.; 63rd St.; 59th St.; 35th St.; Maxwell St.; Taylor St.; Monroe St.; Madison St.; Randolph St.; Chicago Ave.; Fullerton St.; Broadway; Clarendon Ave.; Buena Ave. Anyone who knows Chicago can follow this (at points almost block by block) journey northward, cutting through the city, but also channeled by the logic of the grid—less an ambient flâneur than a surveyor of the city’s structure, cutting, not freely, but along the dotted line.

Halsted Street shows the metropolis as a determined space in which variety abounds, but is always submitted to a predictable structure of control and circulation, a layout of streets and directions, of routes—and not simply a proliferation of intersections and possibilities. While the succession of street signs establishes the locations, Conrad’s film shows a fascination with written signs of all sorts. Halsted Street could be seen as a montage of the written aspects of the urban environment as much as Berlin intercuts gestures and actions. This fascination with the city as a space of textural inscription appears as an element in several city symphonies, but in Halsted Street it constitutes a major thread. This fascination with a city of words and surfaces of writing anticipates one of the major reinventions of the city symphony in the 1970s, Hollis Frampton’s Zorns Lemma (1970), composed primarily of images of signs in New York City arranged in the most abstract of tabular orders: alphabetically. But if Frampton’s film portrays the city as a space of linguistic order and abstraction, the writing in Halsted Street remains anchored to the vectoral logic it traces through urban neighborhoods.

Since the structure of Halsted Street respects the order of the street, the trajectory of the film partly traces a succession of ethnic neighborhoods, marked especially by shop and restaurant signs. Chicago in the early 1930s remained the American city with the largest proportion of foreign-born inhabitants—Jane Hull’s famous immigrant settlement house was at Taylor and Halsted Street, an intersection, which appears in the film. While similarities of faces and gestures may mark people as simply belonging to the Family of Man, signs demarcate different languages and cultural communities. Thus, signs reading “Swedish Restaurant” and “Swedish Records” identify the Chicago Swedish neighborhood around 95th St and its culinary and linguistic identity, while a few minutes later in the film “Lithuanian Gospel Mission” and “Vilnius Printing” indicate the Lithuanian neighborhood located around the stockyards (the major locale of Upton Sinclair’s 1906 novel of social protest The Jungle). As the film continues its trek northward, it passes through several distinct ethnic neighborhoods marked by their signage: “Genuine Italian Sausage,” “Italian Medicines” is followed by “Tienda Mexicana todo a precios bajos” and” Café Mexicana;” a succession of signs in Greek mark Chicago’s Greektown; and towards the end of the film, as Halsted crosses Fullerton St., a series of German and Finnish signs appear.

The street-determined structure of Halsted Street allows the film’s cross- section not only to show the variety of Chicago neighborhoods, but to unfold them successively; we simultaneously sense their separation and their proximity. Not only does the film establish ethnicity through signs, it also shows the diverse sort of neighborhoods defined by their role in the urban economy. Conrad takes us through the stockyards; the street market with its crowds, pushcarts, and diverse commodities around Maxwell Street; the entertainment section in midtown with its movie theaters and burlesque shows; or the city park with horseback riding for the rich at the northern end of the route.

Lest my linear description be misleading, Halsted Street remains very much a montage film, in which cutting between shots carries a heavy freight of comment. A grid of montage interacting with the linear progression of the street constitutes the weft and woof of this closely-woven film. Conrad clearly learned from Soviet filmmakers the rhetorical force of a cut. But unlike many of his European mentors, he does not seek to abstract the meaning from its spatial context. For instance, Conrad ends his brief stockyards sequence by cutting from cattle being herded to the slaughterhouse to pedestrians being directed onto a bus by a cop. This comparison of cattle and workers had become by this time almost a cliché, with similar comparisons appearing in Eisenstein’s 1924 Strike, René Clair’s 1931 À nous la liberté, and, after Conrad’s film is finished, Chaplin’s 1936 Modern Times. A very similar cut occurs in Berlin, intercutting the legs of pedestrians on their way to work, the legs of cattle, and soldiers marching. Berlin’s montage is more seamless in tempo and composition than Conrad’s, but this very elegance blunts its comparison. Is the common link between pedestrians, factory workers, cattle, and soldiers docility or simply leg movement? More crucially, one wonders from where the cattle in Berlin come. There is no spatial logic in which to place them, other than the tabular space of similarity/contrast. In Halsted Street, however, we are located at the stockyard, a defining element of the Chicago economy and of its relation to the national economy (midway between the raw products of the West and the consumer markets of the East).3

Late silent cinema’s tendency to disavow the intertitle and valorize visual communication certainly marks Berlin, which is basically a titleless film. Although a silent film for economic reasons, Halsted Street was made after the coming of sound and bears no such prejudice against the written word, which it both records as part of the urban texture and manipulates ironically in its editing. Written signs identify neighborhoods or locations, but Conrad’s editing also creates a sense of disparity between their literal and figural messages, verbal proclamation, and social reality. An early shot of a vegetable market, for instance, shows a large price sign stuck in a barrel of potatoes setting up commerce and prices as a major motif in the film. The following shot of a large billboard in what looks like an empty lot in this rather rural section of the city proclaims less a spatial than a historical context for the film. The billboard proclaims optimistically “They’re Raising a Family of Girls and Boys and Thumbing their Noses at the Depression Noise.” As a sort of epigram for the film, the ironic presentation of this blithe commercial message of denial of a dire economic reality underscores the film’s attitude of critique, generating a suspicion of all surface messages and calling attention to images of suffering and deprivation. Almost magically the shot cuts to an identically framed shot advertising “Little Farms” for purchase on the installment plan, the selling point for the come-on of the previous billboard. This is followed by shots of other commercial billboards: “First National Bank of Chicago” beside an ad for the Community Fund charity showing a crippled child; an amazingly ironic proclamation for Chicago: “Enjoy Winter!” as a slogan for Gas Heat; and, most tellingly, a poster that self-reflectively proclaims “Watch the Posters,” which cues viewers into Conrad’s own dialectical use of the written message. While Conrad’s film never veers from its one-way journey northward this does not exhaust its structure. An alternative route through this space lies precisely in the possibility of reading, or rather re-reading its signs. Just as Berlin works on both the macro-level which shapes a coherence from the figure of the daily cycle and the city limits, and a micro-level of shot-to-shot correspondences and discords, Halsted Street balances the coherence of its street-bound structure with its shot-to-shot comments.

Perhaps the strongest use of Eisensteinian montage concepts in Halsted Street comes with the collision between images and words that yield new meanings or ironic commentaries. A sign saying “Sausages” is followed by a shot of cattle in the stockyard holding pens; a marquee showing the title of a Barbara Stanwyck movie, A Lost Lady (Alfred E. Green, 1934), is cut with a shot of an indigent lady beggar sitting on the sidewalk. But as legible as these juxtapositions seem, they involve more than simply applying labels to images. The cows must be slaughtered and processed to make sausages (setting up the more political metaphor a few shots later comparing workers and cattle), and the abject nature of the homeless street lady contrasts with the romantic connotations of the Hollywood movie title. Reading in this film takes on a critical function and triggers a transformation in meaning.

Conrad’s montage follows the Soviet aspiration of not only analyzing the world but also of reaching conclusions, and his montage of written signs participates in this dual process. The message “Jesus Saves” appears four separate times in the film, always as part of the urban environment, and usually as a sign on a church or mission for the indigent. In two cases it is followed immediately by images that seem to undercut the supernatural aid the sign promises (cutting to an amputee propelling himself on a cart of the sidewalk in one case, and to a drunk collapsed on the street curb in another). The other montages are a bit more oblique, if potentially more interesting; the first “Jesus Saves” sign is followed by a sign in a meat market advertising “free souvenirs,” and the third “Jesus Saves” sign cuts first to men walking on the sidewalk and then to a billboard with a running cartoon baby proclaiming: “I got Live Power!” The promise of eternal salvation is rendered absurd through this juxtaposition to a commercial claim of super power. This recurring rerouting or undermining of written messages sets up the film’s major counter-current to the order of the depression- era city. Early in the film Conrad makes it clear that there are forces of political opposition and conflict within this city. Halsted Street shows a picket walking with a sign proclaiming “Kroger unfair to its workers.” Not only are written messages in this film to be read ironically and critically, they contend with each other. Thus, the film activates a conflict over meaning and even over the control of urban space.

But the most central visualization of this energy of conflict comes with the film’s major overarching trope which redefines the film’s most obvious structure of the one-way street: the figure I will call “the determined pedestrian.” About a third of the way into the film, and just after the billboard of the speedy baby with “Live Power,” a figure of a young man in an overcoat appears, walking with a determined pace that sets him apart from the other pedestrians in the film. He also stands out because the camera tracks along with him in his consistent right-to-left motion, sharing his sense of direction. As he recurs through the film, appearing in 13 separate shots in the various neighborhoods, he functions as a thread that links the diverse topographies. These regularly occurring tracking shots of his determined strides punctuate the otherwise unmoving shots of the film, setting up a dominant rhythm of moving and static shots. While one tends to align him with the film’s structure, with Halsted Street itself, I think that with repetition and acceleration the relation becomes more complex. Halsted Street structures this urban space; it links, but also keeps apart, the neighborhoods. This figure overcomes the distance of the street; he uses the street to get somewhere and as the film progresses, his pace actually increases, until he is running in his final appearances.

This running figure brings the film to a climax in which the relentless trip up the street melds with the man’s final burst of speed to give a sense of destination. The theme of written signs also reaches a resolution here. We see the man running towards the camera, which films him straight on, abandoning the pattern of tracking alongside him. A street sign for Randolph St. announces the location (close to the middle of the city), and Conrad cuts to a shot of a worker swinging a traffic barrier into place that bears the words “stop” and “danger.” The running man comes to a stop on a street corner and waves as he looks off. With a cut on his sight line, we see the goal of his determined progress up Halsted Street: a marching street demonstration. Conrad cuts back to the man, who gives a raised fist gesture of solidarity and runs out of frame. Signs carried by the demonstrators appear cut together: “Death to the Lynchers”; “They Shall Not Die” (with a sign in the background mentioning the Scottsboro Boys, a notorious, racially charged case of miscarriage of justice that led to “right to a fair trial” legislation). In a wider shot demonstrators move through the frame with banners and signs: “We protest discrimination against Negro workers” and “Cash Relief.” A closer shot shows women and children marching carrying signs, such as “I Need Shoes.” Then a shot centers on a placard reading: “Long live the Solidarity of the Working Class.” A shot of men’s legs walking through the frame is followed by a shot of a traffic light with a globe on top of it saying: “End of System.”

This political demonstration brings to an end the thread of the determined pedestrian and thereby provides one of the purposes of Conrad’s film. As opposed to the double meaning evoked from the signs along the route, the signs carried in the demonstration seem to express messages endorsed by the filmmaker. Yet they remain elements belonging to the urban environment, albeit unique ones, since they are carried by people rather than attached to edifices. They move through space, and they announce direct political statements rather than advertising commodities or places of business. But they remain placed and embodied, not abstract statements appearing, say, in intertitles. The final shot of the series present perhaps Conrad’s wittiest recontexturaliztion of an urban sign. The globe reading “end of system” contrasts sharply with the picket signs. I believe it marked the end (i.e., the terminus) of one of the lines of transportation, perhaps the end of the streetcar system that converges around this midtown location. But Conrad’s editing converts it from practical directional information to a statement, even a call to action, to end the Capitalist system.

Although the street structure running uptown and the determined pedestrian share a common direction, Conrad’s film keeps them separate. The man does not appear again after the protest demonstration and its cluster of signs. But the street continues northward and the film follows it across the Chicago River past the indigent “lost lady” and an empty church with a “for sale” sign, to the clean swept streets and fancy mansions of the northern Lake Shore neighborhood where well-dressed folk promenade the sidewalk. The film ends with scenes within the artificial nature of Lincoln Park as people on horseback ride by. This ending does more than simply follow the street to its end. It brings the film full circle, with the rural-seeming park recalling the country of the opening. Further, the coda coming after the demonstration shows that in spite of the desire of the workers and the pun of the filmmaker, the system still continues and the contrast in neighborhoods remains resonant as we end in a neighborhood of wealth and comfort. The final shot of well-to-do riders is followed by the hand (Conrad’s?), glimpsed in the opening credits in negative, tracing the words “The End.”

Conrad’s neglected masterpiece lacks some technical expertise, evident in its occasional over-exposures and the visual obscurity due to the smaller gauge of 16mm. Certainly the film would not have existed if the filmmaker had not seen the pioneering examples of Vertov and Ruttmann and others, as well as paid attention to the montage lessons Eisenstein provided. But this amateur film shows a grasp of film form and structure I find often more compelling as a mode of dealing with urban space than many of its more famous rivals. It reveals how fertile the conjunction of leftist politics and the concept of an alternative cinema was in the 1930s. I also find that Halsted Street anticipated aspects of the US avant-garde cinema of the 1970s in allowing a single structure—the forward trajectory of the street—to dominate over the more molecular logic of montage relations between shots. The street in Halsted Street cuts a cross-section that reveals the actual spatial relations between neighborhoods and classes as it moves through the city, revealing not simply its diversity, but the way those diverse areas are managed, and opening the possibility of protest and revolt—a process the film itself participates in.